Mesoamerican Art – The Material Cultures of Central America

What is Mesoamerican art and what are the characteristics of Mesoamerican culture? Mesoamerican sculptures and paintings were made by the various Mesoamerican tribes that inhabited modern-day Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica. A rich pantheon of gods, architectural characteristics, a ballgame, trade, cuisine, attire, and art were all shared cultural aspects among Mesoamerican peoples. Let’s discover more about the art of Mesoamerica’s history!

Exploring Mesoamerican Art and Culture

The Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, Mixtec, and Aztecs are some of the most studied Mesoamerican cultures. Mesoamerica’s topography is very diversified, with wet tropical sections, arid deserts, high mountains, and low-lying coastal plains. In 1943, the anthropologist Paul Kirchhoff coined the word “Mesoamerica” to describe these geographic regions as having common cultural elements before European conquest, and the phrase has stuck ever since.

When we talk of Mesoamerican art, we usually mean art created by the people who lived in the region now occupied by Mexico and most of Central America. When people talk of Native North American art, they typically mean indigenous peoples in Canada and the United States, despite the fact that these nations are all geographically part of North America.

Art historians and archeologists have increasingly examined ties between the Southeastern and Southwestern United States and Mesoamerica. Concentrating on these links illustrates how individuals came into contact with one another through commerce, common values, migration, or war.

Mesoamerican Culture and Religion

Much of the art of Mesoamerica is centered around their religious beliefs. Because Mesoamerican religious views and cosmological conceptions were so complicated, generalizing about them is challenging. Throughout Mesoamerica, there existed a widespread notion that the cosmos was divided into two axes: one horizontal and one vertical. The Axis Mundi of the universe is located at the intersection of these two axes. Four directions radiate off the Axis Mundi on the horizontal plane.

The Mesoamerican universe is often divided into three primary realms: heavenly, earthly, and underworld. One Aztec example clarifies this complicated cosmological framework. The horizontal axis of the universe is depicted in a 15th-century artwork from the Codex Féjervary-Mayer. The god Xiuhtecuhtli stands in the middle, at the position of the Axis Mundi. Four nodes extend from this point, forming the Maltese Cross shape. The south is connected with green, the west with blue, the north with yellow, and red is connected to the east.

Mesoamerican Art Through the Ages

Three major Mesoamerican cultures are featured in Mesoamerican art: the Olmec, the Maya, and the Aztecs. Tlatilco, Teotihuacan, Zapotec, Toltec, and Mixtec were among the other indigenous Mesoamerican tribes. Art historians and archeologists have created timelines to aid in the categorizing of Mesoamerican artworks.

1800 BCE – 150 CE: Pre-Classic Period

The Pre-Classic period lasted from 1800 BCE to 150 CE and featured art from the Olmecs, Teotihuacan, Tlatilcos, Mayan, and Zapotecs. Crops such as maize, fruit, cocoa, and root vegetables were the first to be cultivated. For cooking and storing, earthenware and subsequently ceramics were created. With the formation of villages and towns came the establishment of hierarchies. The first pre-Columbian civilization, the Olmec culture, resided in what is now Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, and Honduras. Between 800 and 400 BCE, the Olmec civilization built the first pyramid, La Venta, which served as the heart of Olmec culture.

Producing large heads and masks was one of the most impressive art styles. Diets and crude glyphic writing started to emerge in the works. The Mayan civilization included various Mexican states as well as Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Western Honduras. Teotihuacán and Mayan civilizations acquired much of the Olmec culture. Olmec Mesoamerican sculptures were prized and were later discovered in the tombs of other cultures.

Long before the Aztecs dominated the area, the Tlatilco resided on a lake in Mexico City. Living in reed and mud huts, their craftsmen were widely recognized for producing high quality pottery and figures.

150 CE – 650 CE: Classic Period

The Classic period, which lasted from 150 to 650 CE, was characterized by the Maya and Teotihuacán civilizations. The Olmec traditions that they shared started diverging. The Maya invented the calendar and hieroglyphic script. Scholars established both astronomical studies and mathematics in literary texts. With palaces, pyramids, and ball courts, architectural structures with corbelled vaulted architecture became enormous in scale.

However, the Teotihuacán was preoccupied with politics and business. These initiatives were centered on the Valley of Mexico. This was the era of the megapolis, with Teotihuacán being the world’s sixth biggest city.

Around 600 CE, Teotihuacán’s influence began to wane. Mesoamerican cultures struggled for dominance. Power transferred to lesser districts like Cacaxtla, Xochicalco, and El Tajin without the Teotihuacán. With new structures and Mesoamerican sculptures, art blossomed here.

950 – 1519 CE: Post-Classic Period

Between 900 and 1200 CE, the Toltecs reigned, as the Mayan civilization began to decline. Smaller locations were now interconnected in commerce, creating new chances for art production in both conventional and innovative forms. Shell jewelry and items, as well as jade sculptures, were fashionable among Mesoamerican cultures such as the Mixtec, Toltec, Maya, and Mexica or Aztec. The Mixtecs of Oaxaca were masters of gold and silver workmanship.

Such fine metallurgy was new to Central America as well as Mexico, but artisans in South America’s Andes were already creating comparable products. The Mixtec also created hieroglyphic codices.

The Aztec civilization ruled Central Mexico during this time period. The Aztec culture possessed sophisticated irrigation systems that enabled them to cultivate crop production in all accessible areas. As their power expanded, they began to combine the art of various places into their works. The Aztec civilization ruled all communities in Mexico at the time and was vanquished by Cortes and his warriors during the Spanish Conquest of 1519.

Characteristics of Mesoamerican Art and Architecture

Despite its ethnic diversity, Mesoamerican art had several shared characteristics. This included the usage of 260-day calendars, the significance of green stones such as jadeite, and the application of bird feathers. Most works in Mesoamerican sculpture and painting depicted figural portrayals. Mesoamerican art pieces were utilized for decoration, rituals, presents, and funerals. From visions to metamorphosis and the celestial realms, the mystical was also represented.

Religion was vital in Mesoamerican cultures, driving them to construct temples, pyramids, and amphitheaters to worship gods and for rites and rituals. The very first temple pyramids in Mesoamerican architecture were earth mounds covered with stone.

Steps led up to the temple, which was only accessible to the Mesoamerican aristocracy. The site’s position was significant, and it was created in connection to sacred mountains or otherworldly beings. Pyramids subsequently evolved into multi-leveled structures with single or double sanctuaries. Outdoor places were essential, and they were frequently adorned with vividly painted relief carvings.

Olmec Art

Olmec craftsmen carved masks, colossal heads, and ceremonial artifacts from a single piece of stone. Basalt was typically used to make the heads. Smaller pieces were fashioned from jade or serpentine. La Venta, the heart of Olmec culture in Tabasco, Mexico, is a pyramidal structure that scholars think was formerly aligned with a constellation. The dirt mound is 100 feet tall and has a volcanic appearance. Several tombs were discovered further northward.

Colossal basalt heads exceeding 18 tons, little jade artifacts, and stela, were also discovered. Seven basalt Olmec art altars were found. Altar 4’s bas-relief figure is situated in what appears to be the opening of a cave, grasping a rope. Closer examination reveals eyeballs and teeth in the cornices, and the figure is within the jaws of a beast.

San Lorenzo was founded between 1200 and 900 BCE in the southeast part of Veracruz, Mexico. Archaeologists discovered a palace with an adjoining studio for creating Olmec art statues.

Tlatilco Art

Long before the Aztecs, the Tlatilco constructed their town in the Valley of Mexico, which is now Mexico City. Five hundred burial sites, as well as high-quality ceramics and pottery, were unearthed here. Tlatilco was famed for its handcrafted and vividly painted tiny clay sculptures. The majority of the discovered sculptures are female. Male figures are uncommon and typically wear masks, as if performing religious functions.

One famous Tlatilco female figure is a Mesoamerican funeral artifact dating from 1200 to 900 BCE. The art is extremely detailed, complete with an intricate haircut and paint. Art historians say she resembles a god since she has two faces and three eyes. The piece is now on display at the Princeton University Art Museum.

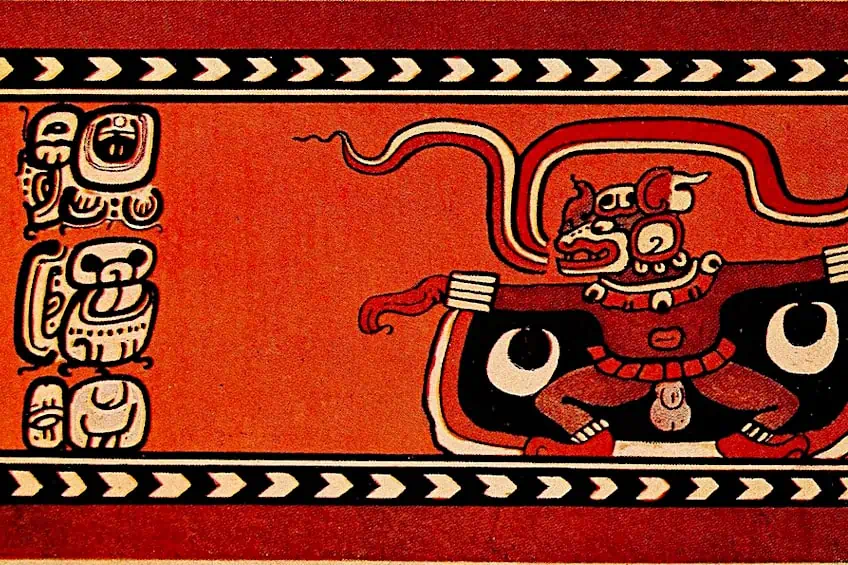

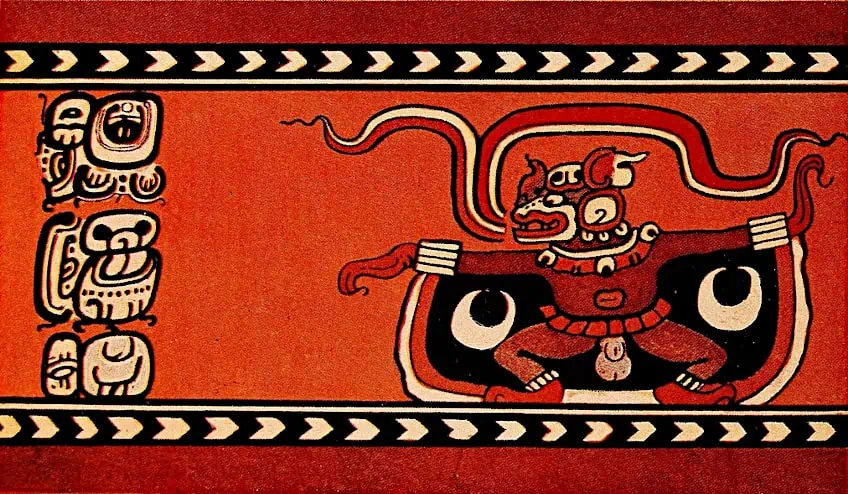

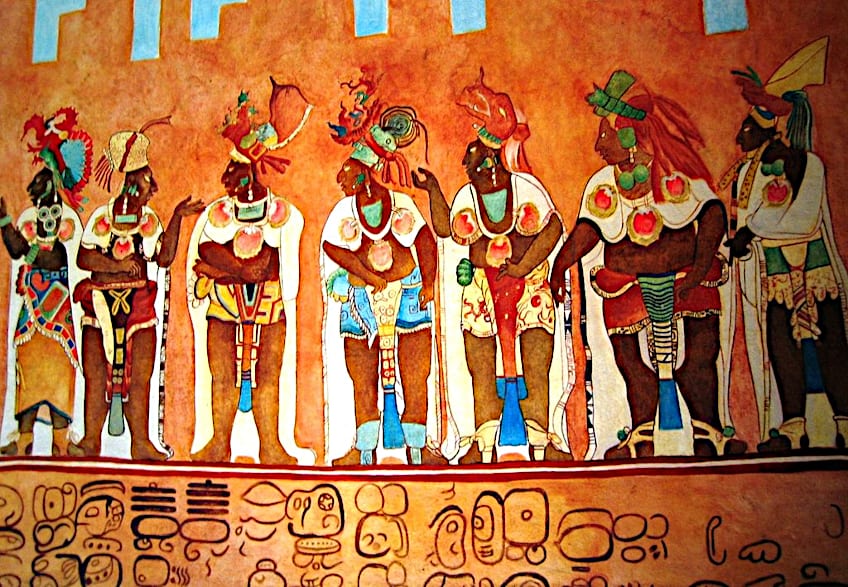

Mayan Art

Mayan artists were elite professionals who worked in workshops to make art pieces for monarchs, priests, and nobility. Some of the pieces were commissioned as grave artifacts, while others were utilized in ceremonies. Codex pottery, tiny sculptures, woodcarvings, massive stone sculptures, mural paintings, stucco modeling, writing, and bookmaking were all examples of Mayan art. A Mayan archaeological site in Chiapas, Mexico, named Bonampak, dating between 580 and 800 CE, is well renowned for its murals. These well-preserved sculptures, which span the walls of three chambers, show Mayan court life, ceremonial rituals, and conflict.

The deity jade figure, positioned in a crab claw stance, is a pre-Columbian artwork. This was characteristic of Maya sculptures during the early Classic period. This might be an anthropomorphic representation of the Principal Bird Deity or a person donning the deity’s mask. Regardless, the figure is decked out with beaded jewelry, including big ear flares, a bracelet, a necklace, and an anklet. The Bird Deity was connected with earth’s riches, particularly jade, which was revered for being exceptionally hard and rare.

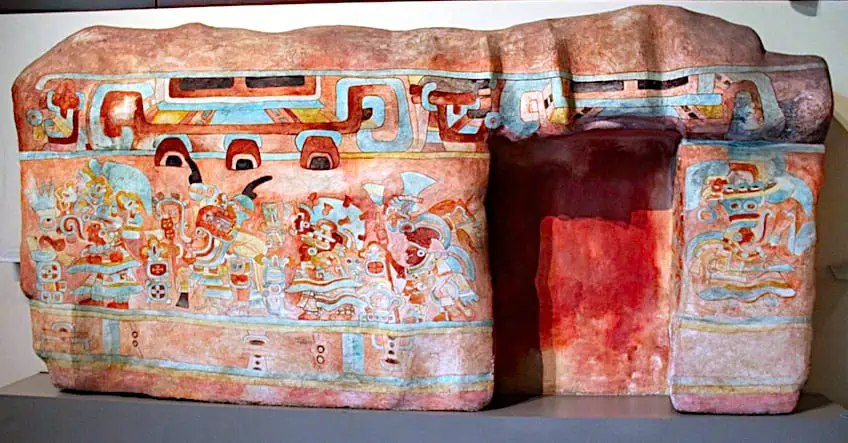

Lintel 24 at Yaxchilán is a limestone carving and painting depicting Yaxchilán and his wife, Ix K’abal Xook, executing a bloodletting ceremony. Copán, another Maya Civilization monument, is located in western Honduras and was constructed during the Classical period. It is well-known for its magnificent masonry and several portrait stelae. The Acropolis, or elevated royal structure, is the heart of the ancient city and is connected to five plazas. The Hieroglyphic Stairway is included. The iconic massive stairwell is built of hand-hewn stone pieces. It is the biggest Mayan inscription ever discovered, with 1,800 distinct characters, and is considered a significant historical find.

The Ballcourt is located just north of this edifice. This is the biggest Classic era find, including 16 mosaic Mesoamerican sculptures of birds. A royal residence on the west side of the Acropolis is accessible through a colossal stairway. Inside one of the constructions here, a seat depicts the King’s ascent to the throne. The Monument Plaza is situated on the northern side of the city center. Altar Q is the most well-known in Copán. It represents the dynastic succession of 16 rulers. Each sits on his own name glyph, revealing much about Mayan society.

Zapotec Art

Mount Alban was the heart of this ancient civilization, the Zapotec culture. It is made up of ceremonial sites, pyramids, an astronomical tower, and platforms devoted to deities and warriors. Before 800 BCE, the Zapotecs were able to develop their own system of writing. So this ancient language that combined sounds and concepts has only been partially understood. Monte Albán’s significance faded virtually abruptly after the year 800 BCE, as it did with other historical sites.

The inhabitants lived peacefully in the valleys of Oaxaca until the conquest of the territories by the Mixtecs drove them to battle and tolerate the imposition of Mixtec religious ceremonies centuries later. In their cultural practices and depictions, the ancient Zapotecs showed profound reverence for their forefathers and deities. The Zapotec sculptures demonstrate this by summarizing their mythology and adoration of the sun, maize, rain, and the sanctity of the land. Their art was dense with concepts about their values, the ideal of peace, displays of power, and allegiance to their rigid political, societal, and military system.

When discussing Zapotec culture and art, one must begin with pottery, which is one of its most profuse forms. For instance, the Mount Alban furnaces were used to manufacture ornamental and practical porcelain for festivities. This discovery is regarded as one of Central America’s most significant expressions. The works were influenced by Teotihuacan’s aesthetic and show bustling economic activities. Later, they were notable for the production of urns, which gave rise to an expression of Zapotec funerary art.

Teotihuacan Art

It’s crucial to note that the category of pictures and things known as “art” is a relatively young phenomenon and that the hierarchies that differentiate art from other types of imagery and items are socially decided and subject to change through time. When we take a step back and consider the function pictures and artifacts played in Teotihuacan, we discover just how deeply they penetrated the city’s everyday and ceremonial places. Not many individuals in ancient Mesoamerica awoke and resided in a residential area filled with interior wall murals, but many individuals in Teotihuacan did.

And that’s just the frescoes; many compounds had little home altars, and specific types of stone Mesoamerican sculptures were common throughout all socioeconomic levels. It was a physically and aesthetically rich world, with even miniature copies of utensils and artifacts found in tombs. Ceramics frequently bore iconography that overlapped with paintings; both were tied to the greater symbolic system seen on the city’s monuments.

Scholars believe that these types of artifacts and pictures helped to integrate the city’s populace by offering a shared and recognized visual language.

Toltec Art

From 900 to 1150 CE, the Toltec civilization ruled Central Mexico from its regional capital Tula. The Toltec people were a warrior society who conquered their surrounding regions and demanded tributes. Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Tlaloc were among their gods. Toltec craftsmen were accomplished architects, crafters, and stonemasons who left a significant aesthetic heritage. The dark, brutal gods of the warring Toltecs demanded victory and sacrifice. They mirrored this in their art, which features numerous representations of gods, soldiers, and priests.

A procession is seen approaching a man clothed as a feathered snake in Building 4’s partially ruined relief, who is most probably a devotee of Quetzalcoatl. The four enormous Atalante sculptures of Tula, the most recognizable work of surviving Toltec art, show fully-armored warriors with customary weaponry and armor, such as the atlátl dart-thrower. At Tula, thousands of ceramic pieces—many shattered, some intact—have been discovered. There is an indication that Tula had its own ceramic industry, however, some of these objects were produced in far-off places and sent there through commerce or tribute.

Later Aztecs praised their abilities, saying Toltec craftsmen “trained the clay to deceive”. Other ceramic varieties unearthed at Tula, such as Papagayo Polychrome and Plumbate, were created elsewhere and came to Tula through commerce or tribute.

The Toltecs produced ceramic of the Mazapan type for both domestic use as well as exporting. The Toltec artists created a wide range of objects, including some with extraordinary faces. The stone carvings and Mesoamerican sculptures are the works of Toltec art that have withstood the test of time the best. Tula is rich in statues and art that has been maintained in stone despite frequent plundering.

Aztec Art

Codices, featherwork, paintings, terra cotta and stone sculptures, and mosaics were examples of Aztec art. During the Aztec empire, the enormous metropolis of Tenochtitlán served as the Aztec empire’s capital. The remains are now right beneath Mexico City. The huge metropolis, which once had about 700,000 residents, was built on a series of inlets on Lake Texcoco. The city was split into four divisions. The Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan stood 164 feet tall in the middle.

The Great Temple, an Aztec religious structure erected between 1375 and 1520 CE, was enclosed in the city center. It featured two shrines devoted to gods upstairs on either side. Human sacrifices were carried out here as part of religious rites to appease the gods.

The massive 11-foot-diameter Coyolxauhqui Stone, sculpted in low relief, was discovered at the bottom of the stairway. The sculptural sculpture depicts bones, skulls, and dead bodies. The famous Calendar Stone, a 12-foot circular representation of the universe, was also discovered here.

Mesoamerican tribes possessed a sophisticated set of beliefs that included natural phenomena like air, earth, water, and fire. They also frequently utilized astral elements like the sun, stars, and constellations. The majority of Mesoamerican civilizations also utilized representations in their art that took the shape of everyday things like braziers or molcajetes, as well as animal and human shapes. The artwork demonstrates that the Mesoamerican pantheon had a variety of gods who were widely revered across Mesoamerica, often even throughout time. The art of Mesoamerica also demonstrates the presence of a universal worldview that includes the chronological order of ages and spatial symbols like birds, cosmic trees, colors, and gods.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Mesoamerican Art?

Mesoamerican art is the visual arts of the Mesoamerican region, which spans most of Central America and sections of Mexico. The art of Mesoamerica has a long history, reaching back to the Pre-Classic period, and it is distinguished by several characteristics, including the use of brilliant colors, highly stylized shapes, and the insertion of symbolic themes and motifs. The Olmec, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, and Aztecs are a few more prominent Mesoamerican cultures that created the most famous art pieces from this region. Similar to the Maya, these societies produced a wide range of works of art, including sculpture, pottery, and architecture, and frequently integrated parts of their respective myths and religions into their works of art.

What Are the Characteristics of Mesoamerican Art?

The use of vivid, strong colors is one of Mesoamerican art’s most remarkable characteristics. A vast variety of colors, including yellow, red, blue, green, and black, were utilized by many Mesoamerican cultures to produce vibrant and eye-catching artwork. These hues were frequently employed to represent significant people or things and to convey symbolic meanings. Also noteworthy about Mesoamerican art are its highly stylized shapes. Many Mesoamerican cultures produced art in a variety of creative genres, including Realism, Abstraction, and stylization. These artistic movements frequently mixed naturalism with expressionistic and symbolic forms, producing artworks that were both strikingly beautiful and full of deep significance. The most famous art pieces in Mesoamerican art are frequently defined by their use of symbolic themes and motifs, in combination with the usage of color and stylized shapes. These patterns and symbols, which were frequently derived from the myths and religions of the many nations, served to express significant concepts and ideas.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Mesoamerican Art – The Material Cultures of Central America.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. April 26, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/mesoamerican-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 26 April). Mesoamerican Art – The Material Cultures of Central America. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/mesoamerican-art/

Davis, Liam. “Mesoamerican Art – The Material Cultures of Central America.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, April 26, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/mesoamerican-art/.