Black Female Artists – 10 Powerful Artists You Should Know

As with almost every aspect of life for a large portion of our past, the narrative of our history has been written and controlled by white men. To be a person of color, as well as a female, meant that your voice was often regarded as irrelevant, and you were left out of the global conversation, whether it be about politics, history, human rights, and even art. Yet, things are starting to change and black female painters are finally getting their moment to shine in the spotlight. This article aims to present the black women artists whose works have drawn global attention.

Important Black Female Artists

Being a black woman artist is no easy task. To begin with, art is a very difficult industry to try to make a decent living in. Especially when you are first starting out, it can be difficult to get your work recognized in such a saturated market. The benefit of living in the digital age is that it has never been easier for artists to get their work out there through the multitude of platforms available nowadays. Yet, this was not always the case, and much of art history was dominated by academia – a realm that remained exclusively available to white males for far too long.

Being an artist is challenging on its own, but when you are also a member of two groups that experience significant prejudices – being black and being female – the challenges can often seem insurmountable. Yet, even amidst all of these massive hurdles, black girl artists have defiantly arisen over the decades to have their voices heard and their art disseminated around the world. A black woman’s artwork is not just an expression of her personal experiences, but also symbolic of the story of all black women. Here is our list of significant black female artists that paved the way for others to follow their dreams of becoming renowned and successful black female painters.

Laura Wheeler Waring (1887 – 1948)

| Artist Name | Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 16 May 1887 |

| Date of Death | 3 February 1948 |

| Place of Birth | Hartford, Connecticut, United States |

Laura Wheeler Waring was born on the 16th of May, 1887, in Hartford, Connecticut, and her upbringing was unique in many ways due to her superior education and middle and upper-class affiliations. In 1906 Waring graduated from high school with honors and subsequently went on to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for a further six years, one of the country’s finest art colleges. In 1914, she was awarded a scholarship that enabled her to pursue her studies in the arts in important European cities for a short time. She returned to work at the Philadelphia Teacher Training School, an all-black institution where she developed music and art programs that she led for almost three decades.

She returned to Europe for a brief trip in 1924, where she created her first paintings, some of which were displayed in Parisian art galleries. Houses at Semur (1925), which she produced in France, received much praise around the art world.

Her artwork was thereafter in high demand at American institutions, notably the Brooklyn Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and thanks to its popularity in Europe. Her most well-known artwork was her portraits, particularly of upper-class black and white individuals such as W.E.B. DuBois, and Leslie Pinckney Hill. The subject matter of her paintings fueled accusations that she was elitist; however, this is unjustified because few individuals outside of the wealthy elite could afford to have professional painters produce their portraits in the first place. She also produced landscapes and murals of both Europe and the United States, for which she received widespread recognition. She stands out from other black women artists of the time not just for her talent, but also for the exceptional amount of formal instruction she received.

Alma W. Thomas (1891 – 1978)

| Artist Name | Alma Woodsey Thomas |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 22 September 1891 |

| Date of Death | 24 February 1978 |

| Place of Birth | Columbus, Georgia, United States |

Alma W. Thomas was the very first black woman artist to hold a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She was also the first African-American woman whose art was purchased by the White House. Her life as an artist was also unique in other ways. She defied society’s preconceptions of women of color born in the 19th century as an artist and global explorer who never wanted to marry anyone or have children. Thomas and her siblings were born into a household that emphasized education and upliftment. After gaining his freedom, their grandfather established a large farm. Thomas’ entire family encouraged her creativity from a young age, and she initially aspired to be an architect.

Her family relocated to Logan Circle in 1907, to an Italianate row house. Academics, business owners, and artists lived in this bustling middle-class Black community.

She became an established figure in education as well as the arts and cultural scene. Her longtime residence in Logan Circle shaped her view of nature. The home was framed by holly and crepe myrtle trees, and she cultivated a garden in the back. Her views of the changes in season from her window inspired her paintings such as Wind Dancing with Spring Flowers (1969). Thomas just wanted to be regarded as an artist, not a black woman artist. Her view was that creativity was not limited by ethnicity or gender. Thomas entered a new artistic era with the arrival of the Space Age. Around this time, she experimented with pointillism. This is an artistic method in which little dots are used to create a larger image. As she once stated, her Space series was inspired by the transition from horse and buggy to spaceship.

Loïs Mailou Jones (1905 – 1998)

| Artist Name | Loïs Mailou Jones |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 3 November 1905 |

| Date of Death | 9 June 1998 |

| Place of Birth | Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

Jones was brought up in Boston in a working-class family who stressed the value of studying and working diligently. Jones started creating textiles for various New York enterprises after graduating from Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts. In 1928, she departed to teach at North Carolina’s Palmer Memorial Institute. There, She established the art department, taught folk dance, coached basketball, and played the piano for Sunday mass. Two years after that, she was invited to join Howard University’s art department in Washington, D.C. There, she mentored multiple generations of African-American painters, including Elizabeth Catlett, David Driskell, and Sylvia Snowden, from 1930 to 1977.

She then started to get attention for the substance and skill of her own artwork.

Jones incorporated African tribal art, a common subject in Parisian exhibitions, into her paintings after taking a year off in Paris. Paris had a significant impression on her, and she was happy to be in a nation where her ethnicity felt inconsequential. Her marriage to Haitian graphic artist Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Nol in 1953 affected her even more since she observed the vivid colors and strong patterns of Haitian art on annual visits to her husband’s homeland. Jones was appointed as a cultural ambassador to Africa by the U.S. Information Agency in 1970. In 11 different countries, she lectured, visited local artists and interviewed them, and also toured various museums. This encounter inspired her to incorporate more African themes into her artwork, particularly in her works from 1971 to 1989.

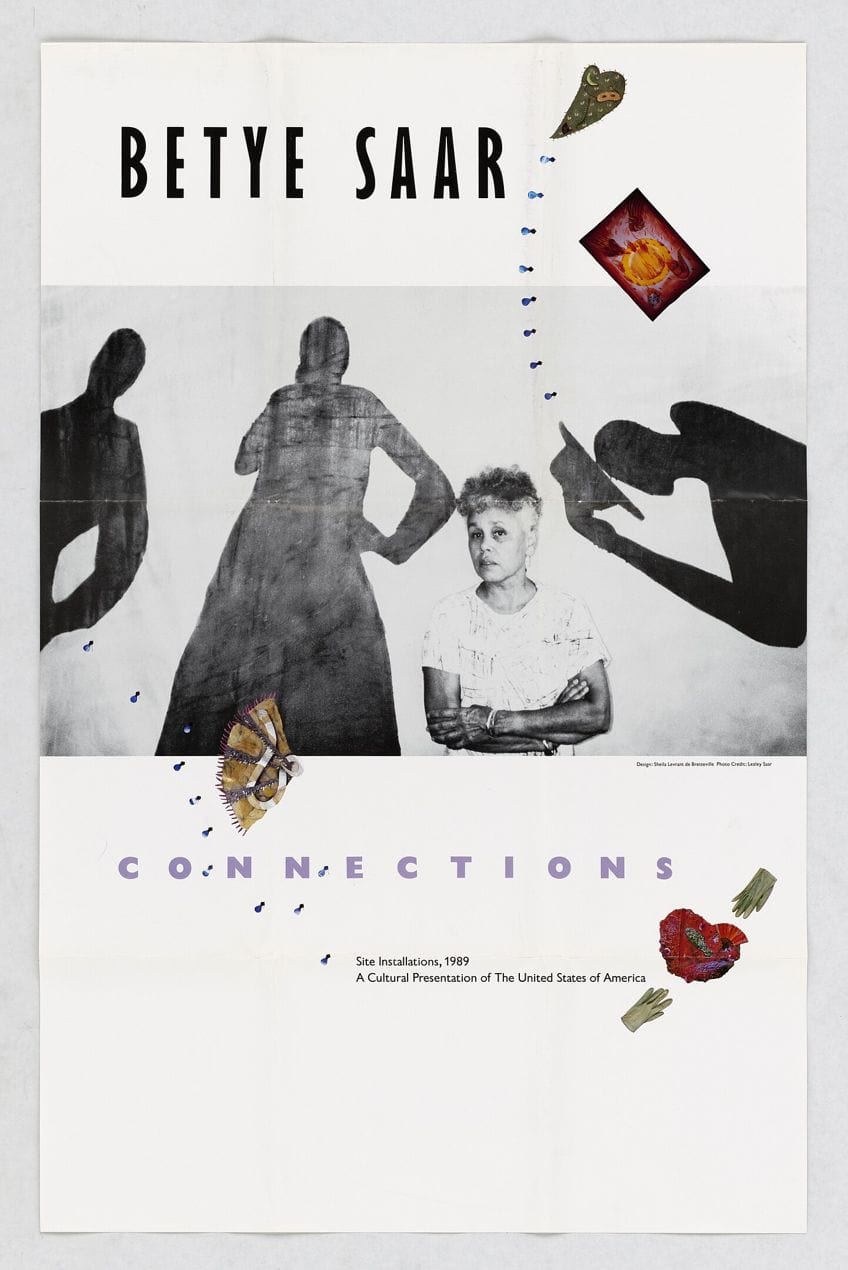

Betye Saar (1926 – Present)

| Artist Name | Betye Irene Saar |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 30 July 1926 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | Los Angeles, California, United States |

Betye Saar’s oeuvre reflects on African-American spirituality, identity, and the interconnectedness of diverse cultures, and she is regarded as one of the artists that ushered in the creation of Assemblage art. Her art has developed throughout time to reflect the cultural, environmental, political, racial, technical, historical, and economic context in which it exists. Her early observations of Simon Rodia’s building methods in the construction of the Watts Towers in Los Angeles brought deeper insights into how discovered materials express both the spiritual and the mechanical.

This goal, together with her own interest in magic, metaphysics, and the occult, gave rise to Saar’s assemblage artworks.

Following her iconic piece, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), she has investigated the societal marginalization of African-Americans in service-oriented professions, the development of racial hierarchies determined by skin tone inside Black communities, and the ways that things can preserve the experiences and histories of their owners. Generations of artists, notably women of color, have been affected by Saar’s oeuvre. Her utilization of found objects and assemblage has inspired many subsequent artists to use ordinary materials in their own works, and her emphasis on racial and gender concerns is still relevant today. By focusing on the lives and viewpoints of Black women, Saar’s work disrupted the mainstream narratives of American art history.

Faith Ringgold (1930 – Present)

| Artist Name | Faith Ringgold |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 8 October 1930 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | New York, New York City, United States |

Ringgold visited Europe in the early 1960s. From 1963 through 1967, she produced her earliest political works, The American People Series, and held her debut and sophomore solo exhibits at the Spectrum Gallery in New York. She started producing tankas (Tibetan artworks framed in lavishly brocaded textiles) in the early 1970s, in addition to soft sculptures and masks. Thereafter, in the 1970s and 1980s, she used this medium in her masked performance pieces. Although Ringgold’s artwork was influenced by African art as early as the 1960s, it wasn’t until the late 1970s that she visited Ghana and Nigeria to explore the rich legacy of masks that has remained her biggest inspiration.

In 1980, she collaborated with Madame Willi Posey, the artist’s mother, to create Echoes of Harlem, her first quilt.

Her tankas from the 1970s were incorporated into the quilts. Her paintings, though, were not only framed with fabric but also quilted, giving her a unique way of working with the quilt medium. She created her very first story quilt, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? in 1983 as a means to disseminate her unfiltered thoughts. Her use of words in her quilts has evolved into a distinct medium and aesthetic of her own. Ringgold’s debut novel, the award-winning Tar Beach, was released by Crown Publishers in 1991. Ringgold’s vivid paintings and quilts explore how socioeconomic developments in the 20th century altered the African-American experience. She has produced fascinating stories about history, brutality, authority, and black identity throughout her career. Ringgold has shown her works in several places, including Paris, London, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Howardena Pindell (1943 – Present)

| Artist Name | Howardena Pindell |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 14 April 1943 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

Howardena Pindell was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She attended Boston University and then Subsequently Yale University. Howardena was reared amid the Women’s Liberation and Civil Rights movements and was heavily affected by them. She is now a teacher, artist, and activist. Pindell’s art addresses sensitive and political issues. Enslavement, racism, violence against indigenous people of color and African-Americans, excessive use of force by police, the AIDS pandemic, and climate change are among the topics covered in her exhibitions. Pindell typically uses extensive, symbolic destruction/reconstruction techniques. She cuts canvases into pieces and then stitches them back together, producing surfaces in phases.

She paints or sketches on paper pieces, then after that, she uses a hole punch to poke out dots from the paper, distributes the dots across her canvas, and lastly pours paint through the “stencil” left in the paper out of which she originally punctured the dots.

Her paintings are almost always mounted unstretched, attached to the wall only by the force of a few nails. Her concern with geometric, sequential imagery, as well as surface textures, is evident throughout her artworks. Pindell is regarded as among the trailblazing black female painters who has utilized her art to address themes of gender, race, and identity consistently throughout her career. She was among a handful of black female artists working in the art industry in the 1970s, and she has kept producing artwork that questions the art world’s prevailing narratives. Her work has received multiple accolades and exhibits, and she is considered a key figure in the development of African-American contemporary art.

Suzanne Jackson (1944 – Present)

| Artist Name | Suzanne Jackson |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 30 January 1944 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | St. Louis, Missouri, United States |

Suzanne Jackson initially traveled west with her family to San Francisco, then on north to Yukon Territory. She grew up in the distant natural surroundings of pre-statehood Alaska before moving to the Bay Area to pursue art, dance, and theater at San Francisco State University and the Pacific Ballet. In 1967, he moved to Echo Park, where she was employed as a teacher and studied drawing with Charles White at Otis Art School. Through Gallery 32, which she operated from her workshop in the Granada Buildings from 1969 until 1970, Jackson engaged a notable collective of artist peers, including Timothy Washington, David Hammons, Dan Concholar, Alonzo Davis, George Evans, Senga Nengudi, Gloria Bohanon, Emory Douglas, and Bety Saar. Jackson has worked in a very diverse range of fields over the course of his lifetime, including painting, sketching, printing, poetry, bookmaking, theater, dance, and costume design.

Figures and repeating symbols are built up by numerous layers of acrylic wash in her works from the 1960s and 1970s, creating airy paintings in which any clear distinction between represented components is eliminated.

Jackson’s most recent “anti-canvases” are partly built with nets, rods, and paper pieces, and are scattered with commonplace things like bamboo, bells, peanut shells, loquat seeds, and leather string. Handmade gestural impressions by the artist – crimping, pinching, and pleating – occur with a transparency that provides each creation with a very poetic and radiant dimensionality. Jackson lives and works in Savannah, Georgia, where she has been since 1996. Her artwork is in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others. In 1990, she also received an MFA in theatrical design from Yale University.

Carrie Mae Weems (1953 – Present)

| Artist Name | Carrie Mae Weems |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 20 April 1953 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | Portland, Oregon, United States |

What does it mean to be a historical witness? Carrie Mae Weems has been pursuing this topic for decades through film, photography, installation, performance, and social practice. Examining the past, according to Weems, means imagining a different future. Her art constantly pushes the boundaries of tradition, and she is determined to discover new ideals to live by. She was trained as a photographer and dancer before enrolling in the University of California folklore studies program, in the mid-1980s when she grew interested in social scientific observation techniques. She began incorporating herself in her photographic creations in the early 1990s in an attempt to generate within the work the simultaneous impression that she was part of it and in it.

She later described this recurring character as a “muse, alter-ego, and historical witness who might represent both the artist and the public.

I believe it is critical that as a black woman, she be involved with the society around her, with history, with seeing, and with being. She’s a guide into situations rarely observed”. Weems utilizes her own personality in her Kitchen Table Series from 1990 to “react to a variety of issues: women’s subjectivity, female’s capacity to luxuriate in her body, and the woman’s creation of herself, and her own image.” Throughout the series, Weems’ protagonist lives in the same small household space. In Woman and Daughter with Makeup, for instance, a lady sits at a table with a small child, and they both look into mirrors at their own reflection, putting on lipstick in synchronized motions. The image demonstrates that gender is a taught behavior while gently focusing its black female subjects.

Mickalene Thomas (1971 – Present)

| Artist Name | Mickalene Thomas |

| Nationality | African-American |

| Date of Birth | 28 January 1971 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | Camden, New Jersey, United States |

Throughout her early career, she became involved in the expanding DIY culture of musicians and artists, which inspired her to create her own artistic output. Mickalene stated that fashion had always been at the back of her mind as a source of creativity when she became an artist. Luminaries such as Romare Bearden, William H. Johnson, and Jacob Lawrence influenced her style significantly. Carrie Mae Weems’ artwork, particularly her Ain’t Jokin series, which was featured in a retrospective at the Portland Art Museum in 1994, had the most influence on her. “That was the first time I encountered works by a black girl artist that represented me and relied upon an understanding of family relationships, related to sex and gender”, Thomas says of the experience.

Mickalene Thomas’ choice to change disciplines and go to Pratt Institute in New York was influenced not just by Weems’ work, but also by her desire to put her experience into art.

Thomas has also indicated that Faith Ringgold had a significant influence in determining her direction. Her portrayals of African-American women address fame and identity while grappling with the depiction of black femininity and power. The protagonists in Thomas’s paintings and collages exude sexuality, which some see as a satire of sexist and racist stereotypes in media, especially music and movies linked with the Blaxploitation genre. Ladies in suggestive positions dominate the visual plane, which is bordered by beautiful patterns inspired by her youth. Thomas’s artwork has been influenced by her years of study in art history, landscape painting, portrait painting, and still life. She has taken inspiration from a variety of artistic eras and cultural influences in art history, notably the early modernists.

Wangechi Mutu (1972 – Present)

| Artist Name | Wangechi Mutu |

| Nationality | Kenyan |

| Date of Birth | 22 June 1972 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | Nairobi, Kenya |

Wangechi Mutu is a visual artist originally from Kenya best known for her paintings, sculptures, films, and live performances. Mutu was born in Nairobi and has since lived and worked in New York City for almost 20 years. Mutu’s artwork explores themes of race, gender, and colonialism using a variety of media, including video, collage, performance, and sculpture. Her work focuses on the brutality and mistreatment of Black women in modern culture. Mutu’s portrayals of femininity are a frequent subject in her art. Mutu employs the feminine topic in her work, even when the forms are unidentifiable, whether through the form itself or the textures and patterns of the figure’s materials.

Her use of ethereal portrayals of women, often in a seductive or sensuous posture, sparks debate over the exploitation of women.

Mutu confronts the hyper-objectification of feminine black bodies in particular and has embraced an otherworldly aspect to emphasize the false nature of society’s portrayals of black women. It is believed that her diverse representations of feminine characteristics, whether through fine linear patterns or classic feminine structures, heighten the impact of the imagery or the significance of the issues raised. Several of Mutu’s artworks have been regarded in contradictory ways, as both participating in a dysfunctional society and optimistic for future change. It’s also been suggested that Mutu’s use of purposefully ugly or unearthly imagery may encourage women to reject society’s ideal of perfection and rather embrace their own imperfections while also being more forgiving of the faults of others. Mutu is capable of enacting cultural and personal transformations by switching from sculpture to painting and back again.

Black woman’s artworks are a very crucial aspect of our culture as a whole. How we treat minorities says a lot about us as a civilization. For too long, the voices of black female artists were muted by the dominant ideals and prejudices of the times. Yet, black women have not idly stood by waiting to be given a chance; they have instead arisen and demanded that their voices and stories be heard, that our lessons as a society be learned, and that the past be acknowledged so that the future may be brighter.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Challenges Faced by Black Women Artists?

African female artists are typically underrepresented in traditional art galleries, institutions, and museums, and their artwork is typically underestimated or dismissed. This might make gaining awareness and acknowledgment for their work challenging. Black female artists also often encounter stereotyping and bias as a result of their ethnicity and gender, which can affect how their work is viewed and interpreted.

What Issues Are Addressed in a Black Woman’s Artworks?

Each artist has an individual and unique story to tell. Yet, there are also common topics that seem to pop up in many black girls’ artworks. This includes addressing issues such as gender and racial discrimination, poverty, and injustices. However, many artists choose to focus on a positive future instead of a problematic past.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Black Female Artists – 10 Powerful Artists You Should Know.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 28, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/black-female-artists/

Davis, L. (2023, 28 September). Black Female Artists – 10 Powerful Artists You Should Know. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/black-female-artists/

Davis, Liam. “Black Female Artists – 10 Powerful Artists You Should Know.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 28, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/black-female-artists/.