Analytical Cubism – The Movement That Made Pablo Picasso

What is Analytic Cubism, and who developed Analytic Cubism? Many are familiar with the art movement of Cubism, which had a widespread impact on the global art community in terms of leading artists to new versions of abstracted realities. But few are aware that Cubism is determined by two distinct styles that emerged in the 20th century. In this article, we will introduce you to the origins of Analytical Cubism, including its characteristics, notable figures who developed the style, and a few Analytical Cubism examples in painting that will shed more insight into the unique techniques used in Analytical Cubism.

Shattering Reality with Analytical Cubism

The Cubist movement emerged in the 20th century as a response to the rapidly-changing conditions of the Modern world, which saw many advancements in technology and cultural reality itself. Cubism aimed to capture as many viewpoints as possible through a fragmentary approach that reflected the diversity and modernity of the 20th century. Representation was thus altered through the movement and many artists embraced alternative versions of reality that begged one to question the fabric of life and the potential for establishing new visual languages. But, what is Analytic Cubism, and who developed Analytic Cubism? Analytical Cubism is often referenced in relation to its sister style, Synthetic Cubism. The distinction between Analytical Cubism vs Synthetic Cubism styles lies in its origin and unique characteristics that make each phase of the Cubist movement powerful in its own right.

The differences in the Analytical Cubism vs Synthetic Cubism phases are defined by the contrast in stylistic preferences in each phase. Analytical Cubism emerged first in an attempt to deconstruct reality and focus on the geometric representation of a new fragmented reality. Synthetic Cubism on the other hand emerged in the 1910s, after Analytical Cubism, and saw artists incorporating more vibrant colors, mixed media collages, real-life materials, newspaper clippings, and unified compositions to represent objects and subjects.

Defining Analytical Cubism

Analytical Cubism can thus be defined as an art style under the Cubist movement that aimed to dissect and analyze form through the geometrization of reality. Analytical Cubism originated in the 20th century with artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque who drew inspiration from African art patterns and geometric forms expressed by the art of Paul Cézanne. Through Picasso and Braque, Analytical Cubism debuted in Paris, France, and was a style that embraced the depiction of objects from multiple angles and distorted the representation of reality as seen in traditional styles.

At the heart of Analytical Cubism was the aim of deconstructing reality as a way of evoking the essence of the object itself through geometric shapes.

Examining the Characteristics of Analytical Cubism

The deconstruction of reality was expressed in geometric forms and shapes that Picasso and Braque experimented with to flatten space and create fragmented forms. Aside from the large influence of geometry and the fractured representation of objects, the characteristics of the Analytical Cubist style also included a subdued and monochromatic color palette, which made artwork appear non-representational and tended toward abstraction.

The Analytical Cubist style was focused on the dissection of reality through the notion that each object or form could be reduced to its essential geometric shape, and although it may look different, it is still a valid representation of that form or object. Analytical Cubist artwork utilized monochrome and subdued colors for many reasons, with many artists seeking to emphasize form and structure by using a limited range of hues or earthy tones to focus on the composition’s formal elements such as line and shape.

The use of subdued colors also enabled artists to analyze forms and deconstruct them easily.

Artists also challenged existing color schemes used to represent reality and intentionally shifted away from imitating nature to conveying the underlying structure of an object. By adopting a monochrome palette, artists also minimized visual distractions and highlighted the relationships of overlapping planes and geometric facets. Ultimately, the choice of a minimal color palette was helpful to the visual unity of the artwork, which aimed to promote the harmony of various formal elements through fragmented and complex compositions.

Key Figures in Analytical Cubism

The artists of the Analytical Cubist style are considered pioneers of unique artworks and Cubism itself in their own domains. Below, we will introduce you to the top three artists of the Analytical Cubism movement whose works shaped the distinct style of Cubism.

Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

| Artist Name | Pablo Ruiz Picasso |

| Date of Birth | 25 October 1881 |

| Date of Death | 8 April 1973 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Cubism, Analytical Cubism, Surrealism, Modern art, Picasso’s Blue Period, Impressionism, and Expressionism |

| Mediums | Painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, and ceramics |

| Famous Artworks | ● The Old Guitarist (1903 – 1904) ● Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) ● Guernica (1937) |

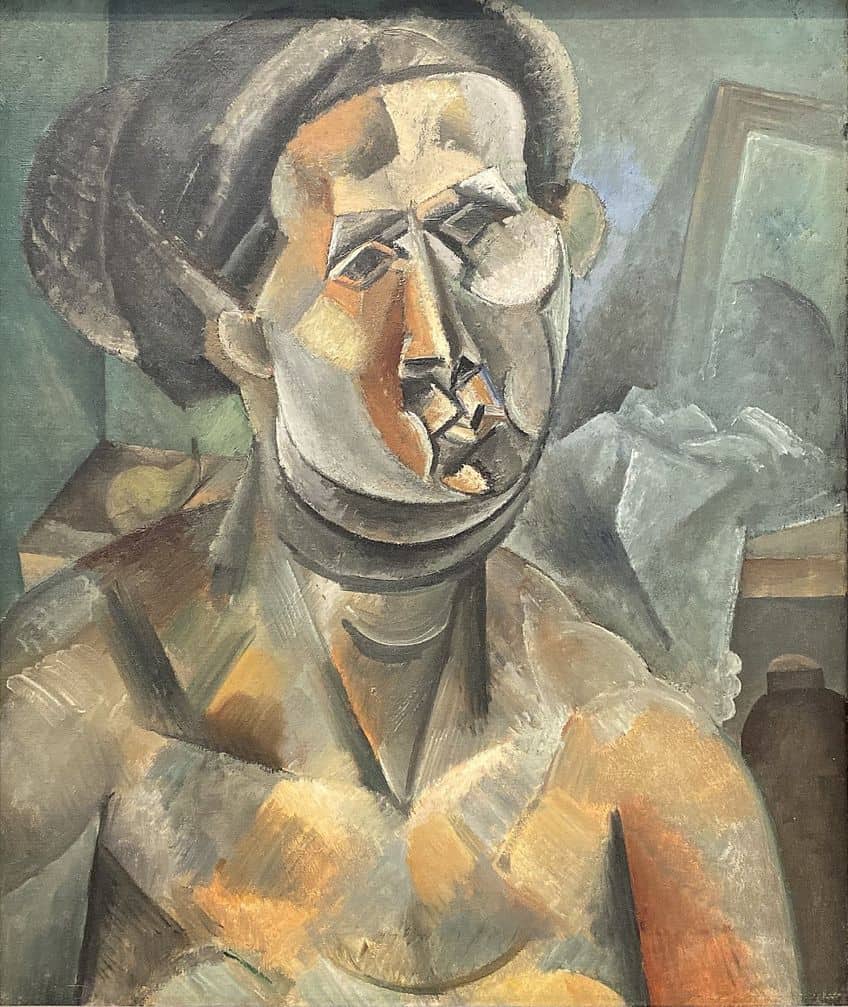

Pablo Picasso was a revolutionary Spanish artist of the Analytical Cubist style and a prolific figure in the 20th-century art world. Picasso played a crucial role in the development of Analytical Cubism, who alongside Georges Braque, pioneered its distinct style through an experimentation with form, space, and perception. Picasso used monochrome palettes across his early Cubist works to emphasize the nature and interaction of geometric shapes and portray objects in their basic geometric forms from multiple angles.

His role in Analytical Cubism was only the beginning of his journey into experimenting with different media and representation through geometric fragmentation.

Among his best-known Analytical Cubist works include Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and Ma Jolie (1911-1912), which both proposed new visual styles for imagining the human form. Picasso worked in a versatile manner while exploring the mediums of painting, sculpture, printmaking, and drawing to create geometrically stylized representations of subjects that he was drawn to and reflected the cultural influences from the Parisian art scene.

Georges Braque (1882 – 1963)

| Artist Name | Georges Braque |

| Date of Birth | 13 May 1882 |

| Date of Death | 31 August 1963 |

| Nationality | French |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Cubism, Analytical Cubism, Modern art, and Fauvism |

| Mediums | Painting, collage, printmaking, drawing, and sculpture |

| Famous Artworks | ● Houses at Estaque (1908) ● Violin and Candlestick (1910) ● Glass on a Table (1910) ● The Portuguese (1911) ● Man with a Guitar (1912) |

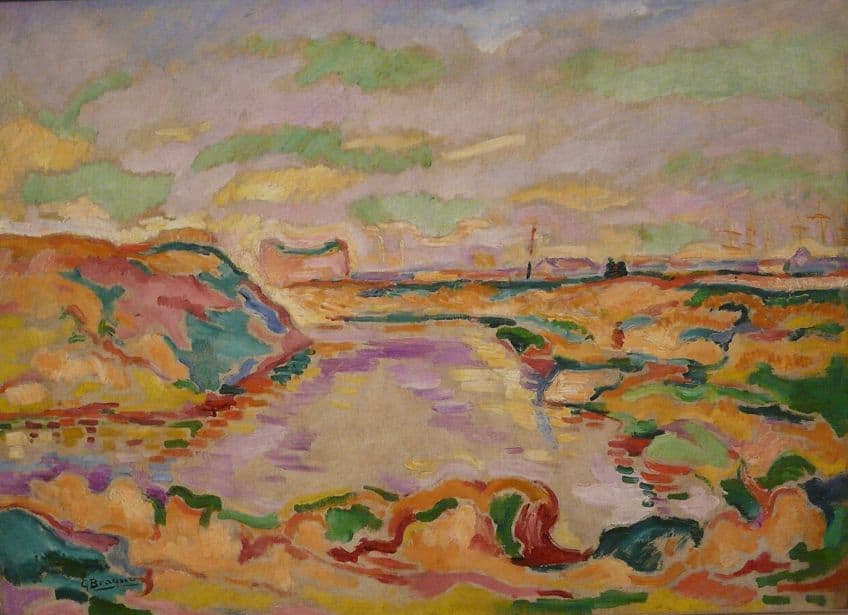

Georges Braque was another pioneer of Analytical Cubism whose distinct earthy monochrome paintings of the early 20th century defined the idea of geometric abstraction and fragmentation itself. Braque’s paintings reflect his obsession with the geometrization of form and space such that his works convey a sculptural depth complemented by his use of bold lines and the occasional curvatures of form that unified his artworks.

Braque’s refinement of fragmented forms and the reassembly of subjects through overlapping planes is what made his work truly unique and complex.

Braque’s use of multiple perspectives in his work also encompasses the essence of Analytical Cubism and was best captured in works such as Houses at L’Estaque (1908) and Violin and Palette (1909), which are proto-Cubist works demonstrating deconstructed images instead of images within images.

Juan Gris (1887 – 1927)

| Artist Name | José Victoriano González-Pérez |

| Date of Birth | 23 March 1887 |

| Date of Death | 11 May 1927 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Cubism, Analytical Cubism, Modern art, and Synthetic Cubism |

| Mediums | Painting and drawing |

| Famous Artworks | ● Juan Legua (1911) ● Portrait of Pablo Picasso (1912) ● Still Life with Checked Tablecloth (1915) ● Harlequin with Guitar (1919) ● The Musician’s Table (1926) |

Juan Gris was perhaps the most talented Analytical Cubist artist who was able to integrate his eye for geometric fragmentation in almost any composition. From still-lifes to portraits and studies of objects, Juan Gris’ unique and refined approach to painting in the Analytical Cubist style was best captured in works like Juan Legua (1911) and Still Life with Checked Tablecloth (1915).

The work of Juan Gris reflects his deep understanding of the fundamental language of the movement as well as his vibrant works that reflected his transition to Synthetic Cubist.

His compositions reflect his meticulous approach to deconstruction and reassemblage of subjects with a sense of dynamism evoked by his use of bold colors. Juan Gris was undoubtedly a key figure in the development of Analytical Cubism and its evolution to embracing a wider range of colors, which made his works pop with vibrancy and playfulness.

Reviewing the Evolution of Analytical Cubism

The evolution of Analytical Cubism can be traced through the development and variation of the art style from color changes to its influential reach into movements like Futurism and Expressionism. As discussed above, the focus of Analytical Cubism narrowed in on the deconstruction of objects into geometric forms and the representation of multiple perspectives in a simultaneous fashion. As the style of the movement evolved, artists began incorporating elements of collage and assemblage, which became the backbone of Synthetic Cubism and blurred the visual language of painting and sculpture through a diverse array of textured surfaces and found objects. One of the 20th century’s most influential movements, Futurism, embraced the modern and fast-paced nature of life that was broadly pioneered by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Futurism carried its own unique style that was certainly distinct from Analytical Cubism, however, similar in that it broke away from traditional conventions by capturing specific visual elements from the modern world and embracing the idea of movement, fragmentation, and multiple perspectives.

While Futurism embraced the movement, movements like Expressionism zoned in on emotional expression and subjective experiences that challenged the notion of form. Expressionism was in a way another artistic approach to distort reality and form by privileging the emotional world and exploring the intensities of the human form and the discombobulation of reality. Expressionism had its connection to Analytical Cubism in its experimental nature that plays with the distortion of form to highlight something other than preconceived realities and structures. Analytical Cubism was thus highly influential in its proposal of alternate fragmented realities and later developments in collage and found objects to the extent that subsequent art movements like Abstract Expressionism, Dadaism, and even Constructivism expanded on the principles of Analytical Cubism.

Analyzing Analytical Cubist Artworks

Now that you have a deeper understanding of the impact of Analytical Cubism styles on the development of art in the 20th century, we will now review a few notable Analytical Cubism examples found in painting that demonstrate the different techniques used in painting to achieve Analytical Cubist styles.

Nus Dans la Forêt (1909 – 1911) by Fernand Léger

| Artist Name | Fernand Léger |

| Date | 1909 – 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 120.5 x 170.5 |

| Where It Is Housed | Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands |

Fernand Léger was another famous Analytical Cubist painter who initially trained as an architect but was more drawn to the idea of envisioning natural shapes and geometry of traditional subjects. Léger’s painting, Nus Dans la Forêt showcases nude figures dancing the forest in an arrangement of mechanized geometric shapes set in subdued and melancholic colors. The painting contains three nude figures and was considered by Léger to be a “battle of volumes”. Through cones, cylinders, and tubes, Léger presents an alternative reality with a rhythmic composition that is a homage to the work of Paul Cézanne, who Léger admired.

Following closely in the footsteps of Cézannian painting, Léger also stuck to the limited color palette of Analytical Cubism and created three distinct nude figures as a way of testing the boundaries of figurative art in a landscape setting.

One can also identify the tree roots at the bottom of the work painted in tubular shapes and is a reference to Cézanne’s view of the natural world defined by shapes and mechanized forms that resembled the Modern world. According to a Contemporary art critic, Léger’s work is also said to resemble modern cinematic stutter effects, which is incredible for the time it was made. In addition to analytical cubist techniques such as fragmentation and geometricization of form, Léger also incorporated elements of distortion and abstraction through the elongation of forms to emphasize their underlying structures. Léger later developed his own unique style called Tubism, which was built on his preference for tubular and cylindrical shapes that were much inspired by a mechanized society. Léger was drawn towards notions of the automaton and android shapes that marked the synthesis of a human and machine figure.

The Portuguese (1911) by George Braque

| Artist Name | George Braque |

| Date | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 116.8 x 81 |

| Where It Is Housed | Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland |

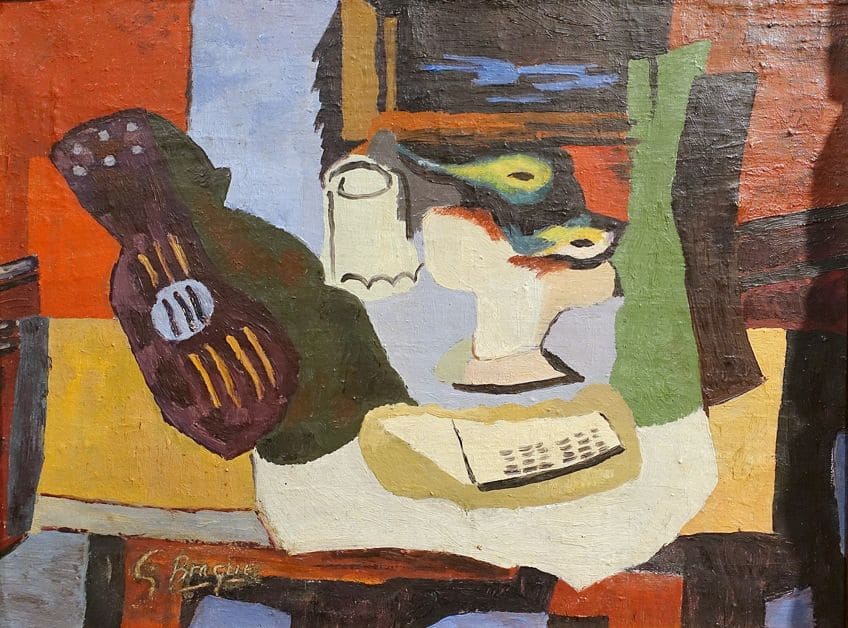

The Portuguese is a famous Analytical Cubist painting by George Braque, which features the artist’s unique stenciled lettering “BAL”. The painting is a rare example of what Braque considered to represent a transition between the Analytical style and the Synthetic Cubist style. To create The Portuguese, Braque used two main techniques. He used stenciled letters and numbers in the work to assert the intentions of the Cubist technique by writing the letters across the surface to emphasize the image’s two-dimensional quality. The painting is considered to be a crucial stage in the development of Braque’s career and one can also see the inscribed letters “DBAL” with numerals marked under them to represent the elements of art. It is believed that Braque’s decision to add the letters was aimed at making viewers aware of the materiality and surface of the canvas.

Through interlocking planes and intersecting planes, Braque was able to create a sense of space and depth in his paintings.

Each plane would also be used to represent different facets or angles of the subject to draw attention to the multifaceted nature of perception. Braque also used a limited color palette that was monochromatic and often subdued accordingly to suit the visual narrative of his analytical cubist language. Braque’s focus revolved primarily around form, structure, and the relationships between shapes as opposed to color, which emerged later with artists like Juan Gris. Later on, Braque introduced elements of collage into his work through found objects, wallpaper, newspaper clippings, and new textures that mimicked wood grain. He was known to employ techniques such as stenciling to enhance the visual experience of his work.

Fruit Dish, Violin, and Bottle (1914) by Pablo Picasso

| Artist Name | Pablo Picasso |

| Date | 1914 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 92 x 73 |

| Where It Is Housed | The National Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

Fruit Dish, Violin, and Bottle is one of Picasso’s best-known Cubist paintings that resembles his transition to Synthetic Cubism. Here, Picasso painted silhouettes, sand grains, and dots to portray different objects and fused different media in the painting to synthesize the color and texture. After deconstructing the different elements in the painting, Picasso synthesized the objects in a modern manner that reflects his move away from his comfort zone, which saw him drawn to suppressed colors as he preferred to focus on the volume and form of objects.

The famous still-life painting part of the permanent collection of the National Gallery in London also described Picasso’s painting as initially appearing abstract, however, upon close inspection, one can identify several objects.

Viewers are guided to observe the work from the bottom up where one can recognize elements of a table, a white tablecloth, a violin, and a segment of a newspaper with the letters “AL” from “JOURNAL”. Picasso selected familiar objects to work with and painted in a very self-conscious way. Artists who painted objects in the analytical cubist style would also paint the object from what they knew of the object and as such, they would emphasize the visual qualities of the objects that seem familiar. Colors would be reduced significantly and the canvas would appear as though it had been folded like an origami artwork.

In 1912, both Picasso and Braque looked to new approaches and techniques for creating Cubist work and incorporated new materials and textures, including rope, fabric, and paper adhered directly onto the canvas. This is what made their works tend toward Synthetic Cubism and was a reversal of their initial approach. Instead of essentializing objects into their basic geometric forms, Picasso and Braque chose to create and synthesize their subjects in terms of color, line, and shape in a more unified composition.

As their composition skills evolved, the two began to create works that contained more recognizable motifs painted from multiple points of view. What makes this painting stand between Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism is that it is not as “busy” as traditional Synthetic Cubist works and is more accessible to the viewer’s eye with the additional space. The arrangement of recognizable shapes such as the violin’s neck and the vertical table legs allows the viewer to scan the pictorial elements, which are well distributed across the canvas and create a sense of classical symmetry.

Criticisms and Controversies

The art world of the 20th century received and responded to the unique art style championed by Braque, Picasso, and many others with both admiration and controversy. At first, the reception of such unconventional means of representation and use of perspective was a challenge for critics to accept, however, the movement’s genius artists and their innovative techniques inspired many artists of the generation to pursue further inquiries into the ideas of abstraction and notions of representing reality, which led to many debates in the art community and among the public.

Among the criticisms of the movement’s developing style, the artists who embraced Analytical Cubism were criticized for their lack of representational clarity as well as for privileging intellectual elitism, which claimed that the movement was too intellectual for the majority of the public to understand.

Other arguments against the movement included the notion that it disrupted the traditional notions of Realism and promoted a sense of chaos, leading to frustration and confusion. The unfinished appearance of Analytical Cubism paintings infuriated those who preferred the conventional forms and approaches to depict form as opposed to an aesthetic dissonance, which proved inaccessible to the wider audience. Specific Analytical Cubism examples in painting such as Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) were particularly controversial in the art world at the time since they challenged existing notions of beauty and the female form by reducing women to basic geometric shapes. The abstraction and fragmentation of women and beauty itself was a mind-altering idea that many critics viewed as a radical act.

Not only was beauty and representation controversial for Picasso, but it also narrowed in on the representation of five prostitutes, which made the work confrontation to conservative critics for exhibiting a sexually charged artwork. The angular shapes of the female form were difficult for the public to accept since it had never been seen or fathomed in reality and as such, it was more of a joke. Over time, the painting and its revolutionary style gained more admiration in retrospect for its unique qualities, which are still critiqued in terms of Picasso and his view of women, the unnamed women in his painting, and his role as a pioneer of the Analytical Cubist style.

Legacy and Significance

The influence and impact of Analytical Cubism were felt beyond the 20th century and continue to move artists of the Contemporary decade who study the works of these revolutionary thinkers and creators. Analytical Cubism forged the path forward to a widespread conceptual shift in the 20th century, which enabled artists to embrace alternative modes of representation and consider new art styles that promoted non-representational art and abstract art. The breakdown of forms and structures invited new possibilities for artists to explore abstraction and its ability to represent multiple viewpoints that challenged the human complexities of perception.

Fixed views on representation declined and as time progressed, the 20th century saw the development of numerous art movements inspired by the innovative nature of Analytical Cubism, which encouraged artists to explore different techniques.

The notion of materiality also shifted over the last century since Analytical Cubism expanded the horizons of materials in art through the incorporation of found objects, collage, and assemblage art as seen in Synthetic Cubism. Such practices had a profound and lasting impact on the art of the late 20th century, which became incredibly influential to artists in the 21st century. Analytical Cubism paintings continue to be a valuable tool for studying art elements and composition techniques in Contemporary art education. Drawing from the style’s emphasis on form fragmentation, the analysis of spatial relationships, and multiple perspectives, art students will be able to access alternative approaches to understanding the principles of line, shape, color, and composition.

By analyzing Analytical Cubist artworks, one can be sure to deepen their understanding of the manipulation of visual elements in a way that fosters one’s ability to create compelling artworks. The Analytical Cubism movement presented many unique insights into how one can perceive and reconstruct a reality that enriches one’s outlook on art and representation. Prominent figures such as Picasso are also controversial in their ideas about representing women, however, the lessons in representation, visual forms, and how these translate conceptually are valuable to Contemporary minds today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Analytic Cubism?

The 20th-century art movement known as Analytical Cubism was the first phase of the Cubist movement that was characterized by the visual deconstruction and reassembly of objects and subjects into their basic geometric forms. The movement also focused on the use of multiple perspectives simultaneously in artwork and emphasized the fragmented and abstract versions of reality.

Who Are the Most Famous Analytical Cubism Artists?

Among the most famous artists of the Analytical Cubism movement include Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Fernand Léger.

What Is the Most Famous Analytical Cubism Artwork?

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) by Pablo Picasso is considered to be among the most famous artworks of the Analytical Cubism movement.

Nicolene Burger, a South African multimedia artist and creative consultant, specializes in oil painting and performance art. She earned her BA in Visual Arts from Stellenbosch University in 2017. Nicolene’s artistic journey includes exhibitions in South Korea, participation in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, and solo exhibitions. She is currently pursuing a practice-based master’s degree in theater and performance. Nicolene focuses on fostering sustainable creative practices and offers coaching sessions for fellow artists, emphasizing the profound communicative power of art for healing and connection. Nicolene writes blog posts on art history for artfilemagazine with a focus on famous artists and contemporary art.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and about us.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, “Analytical Cubism – The Movement That Made Pablo Picasso.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 2, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/analytical-cubism/

Burger, N. (2023, 2 August). Analytical Cubism – The Movement That Made Pablo Picasso. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/analytical-cubism/

Burger, Nicolene. “Analytical Cubism – The Movement That Made Pablo Picasso.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 2, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/analytical-cubism/.