Constructivism Art – Discover the Modern Soviet Movement

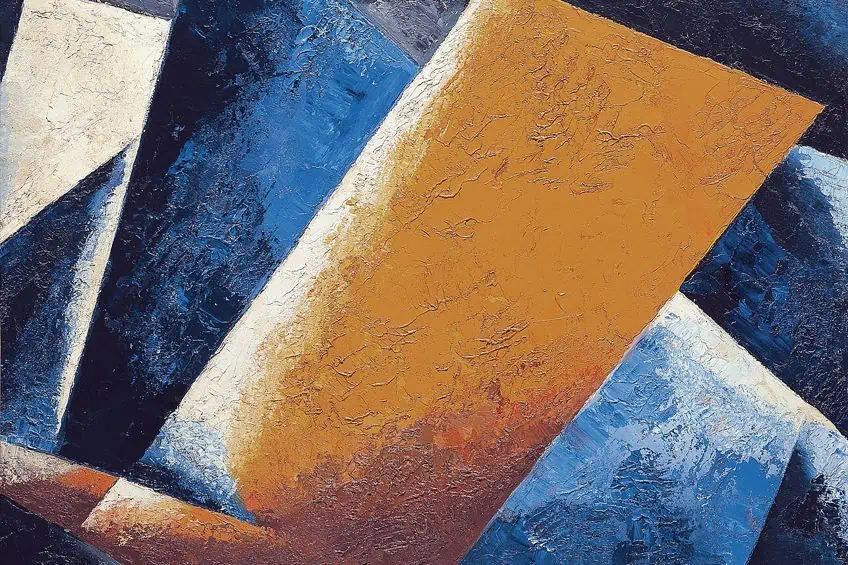

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Constructivism emerged as the art of a new Soviet Union. At its height between 1912 and 1935, Russian Constructivism was one of the most influential art movements of the 20th century, even though it was something of an attack on art itself. Aesthetically rooted in Suprematism, the Constructivism art movement reflected the socio-political agency of the Russian avant-garde.

The Solid Foundation of Russian Constructivism

The Constructivism art movement was not only influenced by the Russian socio-political context but by other art movements occurring around the globe during the early 20th century. In the progressive new era of socialist Soviet history, artists sought a new aesthetic language. Borrowing from European avant-garde movements such as Cubism and Futurism, Russian Constructivism approached artmaking as a process of construction rather than composition.

Understanding Constructivism

Russian Constructivism is an early twentieth-century art, architecture, and design movement. It is sometimes called Soviet Constructivism. It was influenced by Cubism, and Russian Futurism and associated with Soviet Social Realism but Constructivism stood out from these art movements because instead of placing value in aesthetic appearance, it equated beauty with functionality.

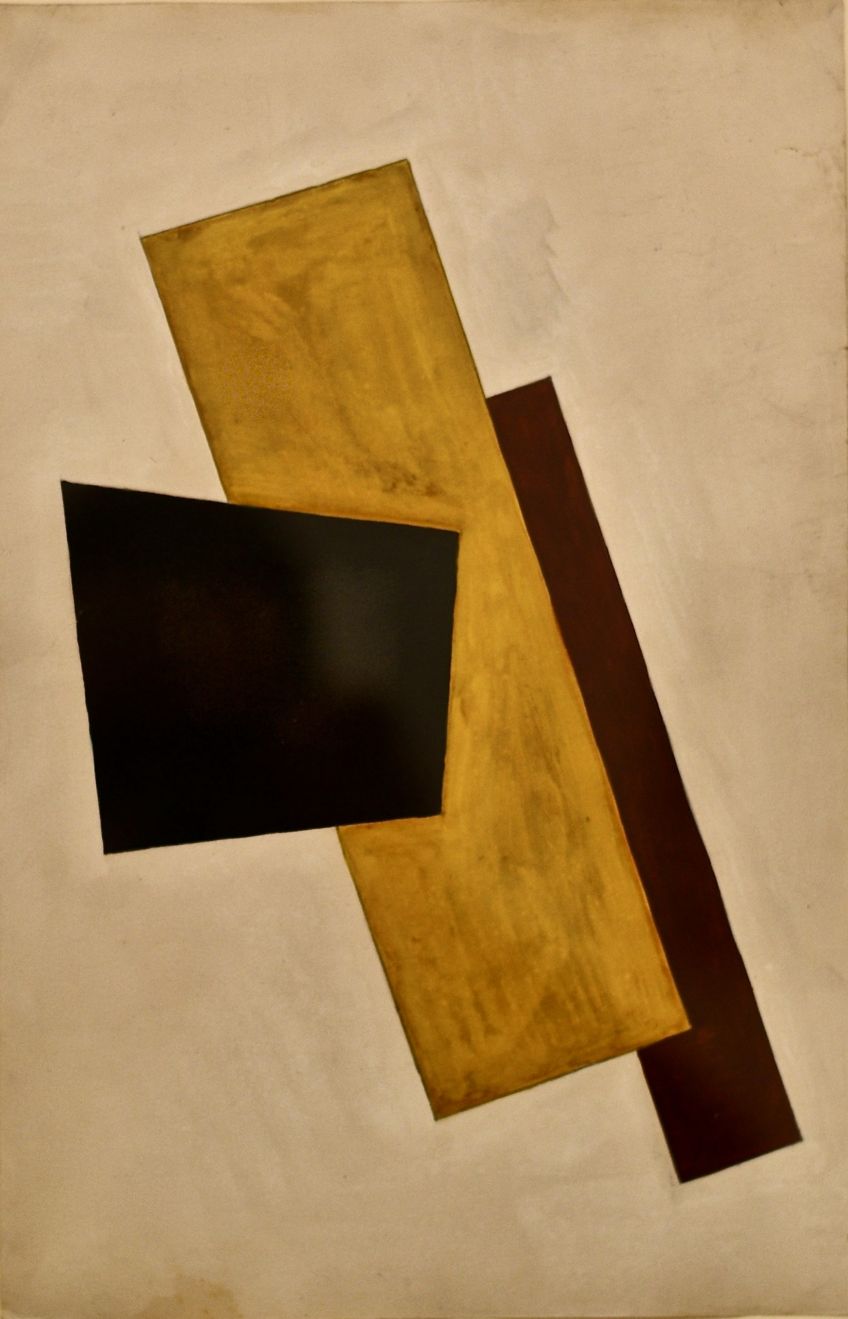

The Constructivism art movement was founded on the notion that painting was dead. Russian avant-garde artists aimed to reinvent the purpose of art. They rejected the concept of aesthetics, abandoning decorative stylization and artistic expression. Instead of art for art’s sake, Russian Constructivism artists attempted through their austere Constructivism art to embody a utilitarian style using minimal geometric shapes.

Russian Constructivism artists believed art ought to reflect urban space and its modern industrial context.

They valued building and science over the artistic touch. They favored the industrial assemblage of materials, using simplified forms to explore materials and spatial properties. The term Constructivism describes these artistic constructions intended to appear as if they were produced in factories or laboratories, emphasizing the utility of their design.

The departure from the convention of art as a commodity was the Russian Constructivism ideal. But the Constructivism art movement was much more than an aesthetic style. It promoted notions of intellectual production and aligned with the values of the Bolshevik communist government. During the early development of the Soviet Union, Russian Constructivism artists used their Constructivism art as propaganda.

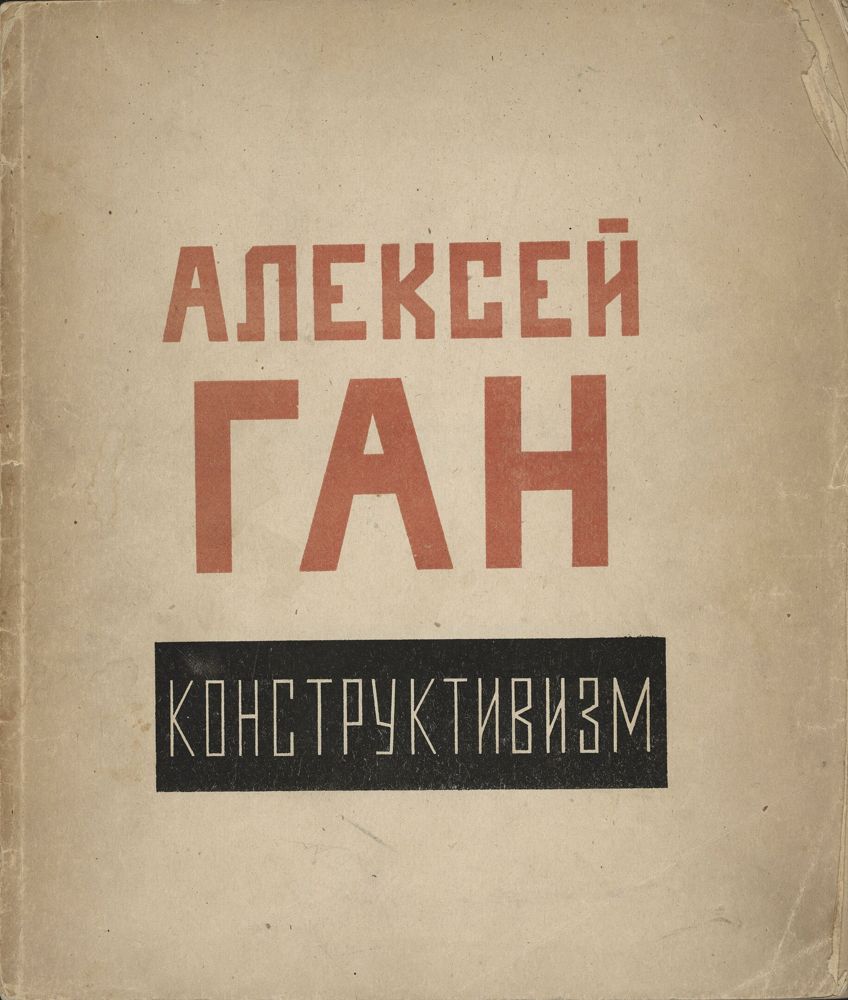

While it was present in Vladimir Tatlin’s Counter Reliefs (1915), the term Constructivism first appeared in Naum Gabo’s Realistic Manifesto (1920) and Aleksei Gan’s book Constructivism (1922). Among artists such as Boris Arvatov, Liubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, and Aleksandr Rodchenko, The First Working Group of Constructivists also included theorists like Osip Brik and Aleksei Gan. Through Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich is often also credited for greatly influencing the development of this geometric, industrial style of avant-garde art.

The Evolution of Constructivism Art

In the 17th and 18th centuries religion, wealth, and power were controlled by an absolute monarchy. During the early 1900s, the reign of Tzar Nicholas the Second was becoming increasingly unpopular due to corruption and nepotism, among other things. Destitution, poverty, and starvation were all too common compared to Western Europe which was more modernized at that time.

The Russian Revolution otherwise known as the October Revolution broke out in 1917 as World War One loomed. This revolution overthrew the provincial government, and the ruling elite, thrusting the country into a civil war. Eventually, the Red Army defeated the Mensheviks or counter-revolutionary whites on behalf of the Bolsheviks, a Communist Party.

The Bolsheviks pushed what they saw as the people’s revolution.

As the nation’s wealth was produced by its people, they believed it should be distributed equally among them. Seizing control of the country, they were ordinary people and members of the working class. Of course, this drastic shift of power combined with the technological and industrial advancements of the 20th century greatly affected the country’s social, economic, and political landscape.

These developments made Russia a breeding ground for all kinds of revolutions including an artistic one. Russian Futurism emerged in the post-World War One era, closely followed by Constructivism. In essence, Constructivism was the Russian fraction of Modernism. The practice and theory of the Constructivism art movement were conceived mainly during a sequence of debates hosted between 1920 and 1922 by the Moscow-based Institute of Artistic Culture.

The movement was utopian, taking its cues from the newly formed Soviet Union led then by the leading figure in the Bolshevik party, Vladimir Lenin, and the Russian intelligentsia who wished to establish a paradise for all of Russia’s people. During the Russian Revolution, Lenin’s political collaborator, the journalist Leon Trotsky was an avid patron of Russian Constructivism artists.

By the mid-1930s, Joseph Stalin and his bureaucratic regime had come to power. Under Stalinism, Lenin and Trotsky became targets of political heresy. Lenin had to go into hiding and Trotsky was exiled, and eventually assassinated. As these leaders had been such staunch supporters of the Constructivism art movement, it fell out of favor with the Communist Party. By about 1934, the counter-doctrine of Socialist Realism was promoted as a replacement for Constructivism.

Constructivism Art Characteristics

Initial Russian Constructivism artists like Varvara Stepanova, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Karl Ioganson, Vladimir, and Georgii Stenberg focused on Constructivist sculpture. Their construction of objects was rooted in the rationale of productivity. They were responding to the rapid spread of mass production through machinery during the Industrial Revolution. Constructivist sculpture was interested in functional objects designed using industrial materials and they believed in the purity of their materials.

The Constructivist sculpture technique was an ideal representation of the values of communism and became an instrument for political propaganda. It was deemed politically appropriate for its amplification of the progressive industrial advancements that the communist system would supposedly deliver to Russia. Russian Constructivism artists made that served the ideological aims of the new Soviet society.

As modern society’s cultural workers, they searched for solutions for the integration of art and life.

Constructivism art then assumed the overall principle of being a combination of faktura and tektonika. Faktura or texture refers to the conscious choice of material and tektonika being its spatial presence. Eventually, two-dimensional works posters, or books became important to Russian Constructivism. Because they had a propagandist agenda, these designs used simple imagery, often of the human face or figure. The characteristic color scheme of Constructivism art was white, red, and black, pigments that were readily available in Russia.

The Russian Revolution and the Industrial Revolution that were occurring at the time resulted in a revolution in politics and art. Not unlike Futurism, Russian Constructivism was inspired by the aesthetic quality of the mechanical age. Unlike Cubism, they did not attempt to express beauty nor to create any illusion of reality. Instead, Constructivism artists used their constructed geometric forms to reject the traditional academic art principles of composition, developing a more modern, industrial style.

Passion or Propaganda

Propaganda was undoubtedly a prominent function of Russian Constructivism. In art, propaganda refers to the systematic and deliberate attempt to shape and manipulate a viewer’s perception. By doing this, a propagandist may achieve a specific response or direct behaviors toward the desired outcome. When art is either for or against a political cause, it can inspire action or a change of mindset within the viewer. Essentially, any form of art associated with propaganda can be seen as a form of political art.

While some may criticize the Constructivism art movement for its foundation in propaganda, this artistic drive is not uncommon. Propaganda can be found across the ages of human civilization, as seen in the large, multilingual, rock-relief Behistun Inscription (c. 515 BC) found at Mount Behistun in Iran. Propaganda manifests itself through various forms of media, but it became far more instrumental after the invention of the printing press and the advent of graphic design.

The Soviet Union is well known for its use of pro-government and pro-establishment propaganda.

This type of propaganda paints authority in a positive light and the Russian constructivists did just that. This meant that the art was heavily regulated and disseminated through the Russian government being biased toward their own political agenda. For this reason, this was an art form that did not necessarily prioritize the well-being of the viewer. While it was used mostly in posters, newspapers, books, or films, this type of propaganda tended to rely on exaggeration and sometimes disinformation. In the most extreme examples, propaganda banned the truth and preferred to promote the country or its leaders through easily accessible messaging with a patriotic point of view.

Simply due to logistical issues, red was a prominent color in Constructivism art to the point where it became synonymous with the communist regime. It eventually became known as Soviet Red and to this day red has retained communist associations. Despite the Communist party’s increased animosity towards all things avant-garde Russian Constructivism artists such as Stepanova, Rodchenko, and Lissitzky continued to work in the service of their nation.

Constructivism Artists

Russian Constructivism artists made art that benefited their culture and society. They believed in a socialist utopia and were determined to reinvent art. Rejecting all notions of representation and pure beauty. Composition was deemed too subjective as it was influenced by an artist’s taste, personality, and emotions. Through various artworks, artists like Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin opted for abstract, geometric shapes in their analysis of the limits of painting.

Exploring the planar surface of their objects, they investigated how elements were placed on a two-dimensional surface in relation to one another.

Their work had nothing to do with subjective artistic expression. Russian Constructivists were contributing to the construction of the new utopian Soviet nation and their art was therefore thoroughly public and political. They did not see themselves as artists but as scientists or engineers. Their utilitarian and unromantic manifestos placed them within the logical systems of the Industrial Age.

Vladimir Tatlin

| Date of Birth | 28 December 1885 |

| Date of Death | 31 May 1953 |

| Place | Moscow, Russia |

| Associated Art Movements | Constructivism |

| Nationality | Russian |

The term sculpture is derived from the action of sculpting which indicates making something by hand, whether it is chiseling marble or shaping clay. Russian painter, sculptor, and architect Vladimir Tatlin is considered the first of the Russian Constructivists to question this notion of a process of sensitive handling of form and innovation using industrial materials.

In 1913 Tatlin visited Pablo Picasso’s Paris studio and became fascinated by a series of three-dimensional reliefs. Influenced by Picasso, Tatlin produced his own abstract assemblages called Corner Counter Reliefs(1914-1915). The reliefs were exhibited in 1915-1916 at the “Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10” in Petrograd. This show would however become a triumph for Constructivism’s counterpart Suprematism.

Nonetheless, Corner Counter Reliefs which were constructed out of plaster, iron, glass, and wood were an important step for Tatlin. Counter reliefs are achieved through a sculptural process where casting, carving, or embossing protrudes beneath the main surface area. The Corner Counter Relief is suspended in the corner of the room in what is known as the “beautiful corner” in Russia. In orthodox Russian homes, that spot in the corner of a room was reserved for sacred Christian icons.

One of Tatlin’s most well-known artworks is The Monument for the Third International (1919-1920) is considered the birth point of Constructivism. But it was Tatlin’s final major artwork Letatlin (1929-1932) that gained him critical acclaim. This project was an expression of the artist’s interest in movement, harmony, and the forms of nature. Tatlin assembled a team of researchers to scrutinize the wings of birds and fathom their structure.

The artist was interested in the efficiency of birds in flight. Birds could travel long distances without an excessive expenditure of energy.

To the human eye, birds in flight could appear motionless. Tatlin used modern machines and experimented with industrial materials to emulate these efficiently elegant natural structures and construct a man-made winged mechanism. Using silk, whalebone, wood, and metal, Tatlin constructed the surface as the space. Letatlin solidified Tatlin’s reputation as an iconic and innovative engineer.

El Lissitzky

| Date of Birth | 23 November 1890 |

| Date of Death | 30 December 1941 |

| Place | Moscow, Russia |

| Associated Art Movements | Suprematism and Constructivism |

| Nationality | Russian |

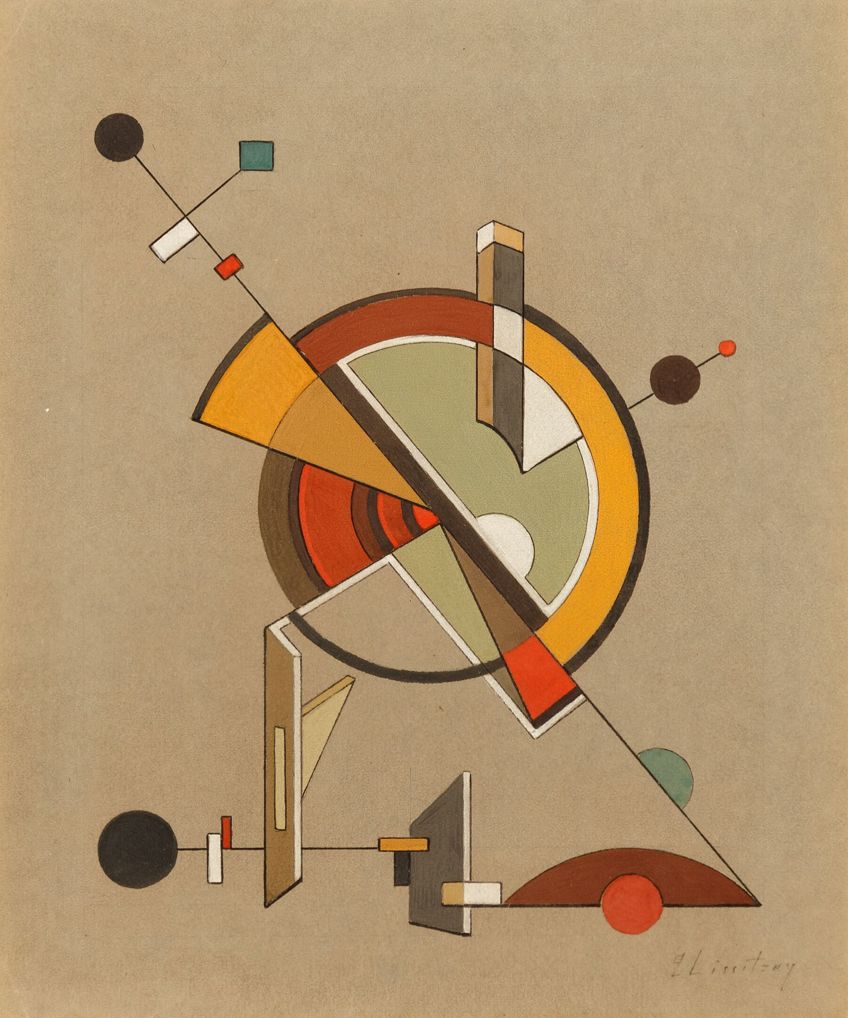

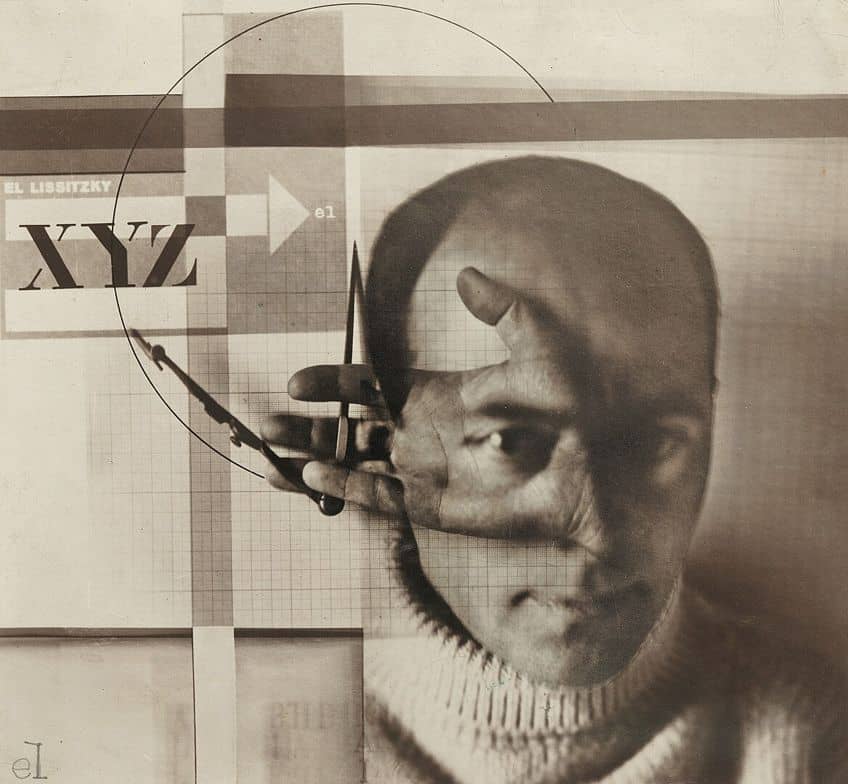

Russian Constructivism artist Lazar Markovich Lissitzky had been one of Kazimir Malevich’s students and became one of the major Constructivist figures. He was more popularly known as El Lissitzky. Having been associated with the shift from Suprematism to Constructivism, Lissitzky contributed to the evolution of the language of the Russian avant-garde.

Lissitzky’s Russian Civil War propaganda poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) is a symbol of support for the Bolshevik Red Army in the struggle against the anti-Communist White Army. The basic geometric shapes and the color combination of white, red, and black are combined with impactful messaging.

The impression of the white being penetrated by red is repeated across the composition through smaller geometric shapes, while the text directs the viewer along the trajectory of the dominant red triangle. The red triangle that represents communists pierces the white circle which represents the bourgeoisie.

Russian Constructivism was all about planning and building. Russian avant-garde artists were no longer limiting themselves to the conventions of traditional art. Lissitzky’s photomontage Self-Portrait (1924), which is more commonly called The Constructor demonstrates how the artist viewed himself. Made from a combination of six different images, The Constructor illustrates the connection between the artist as image maker and constructor, by highlighting the role of the eye and the hand in the process.

As part of the revolutionary movement from around 1919, Lissitzky turned to Vladimir Tatlin’s Corner Counter Reliefs and produced his Prouns (1922).

As in Prouns, Lissitzky seems to be using the simplicity of forms and materials to create a dynamic spatial environment. His basic geometric shapes and simple flat colors mingle with the paint and plywood to create an engaging experience. The assembly of these elements activates the edges and the corners of the exhibition space, giving the work a three-dimensional complexity. As the work sprawls across the walls the room becomes a part of the installation. In order to engage, the viewer must meander within the work, gravitating from one side to another and from one wall to another.

Aleksandr Rodchenko

| Date of Birth | 5 December 1891 |

| Date of Death | 3 December 1956 |

| Place | Moscow, Russia |

| Associated Art Movements | Constructivism and Modern art |

| Nationality | Russian |

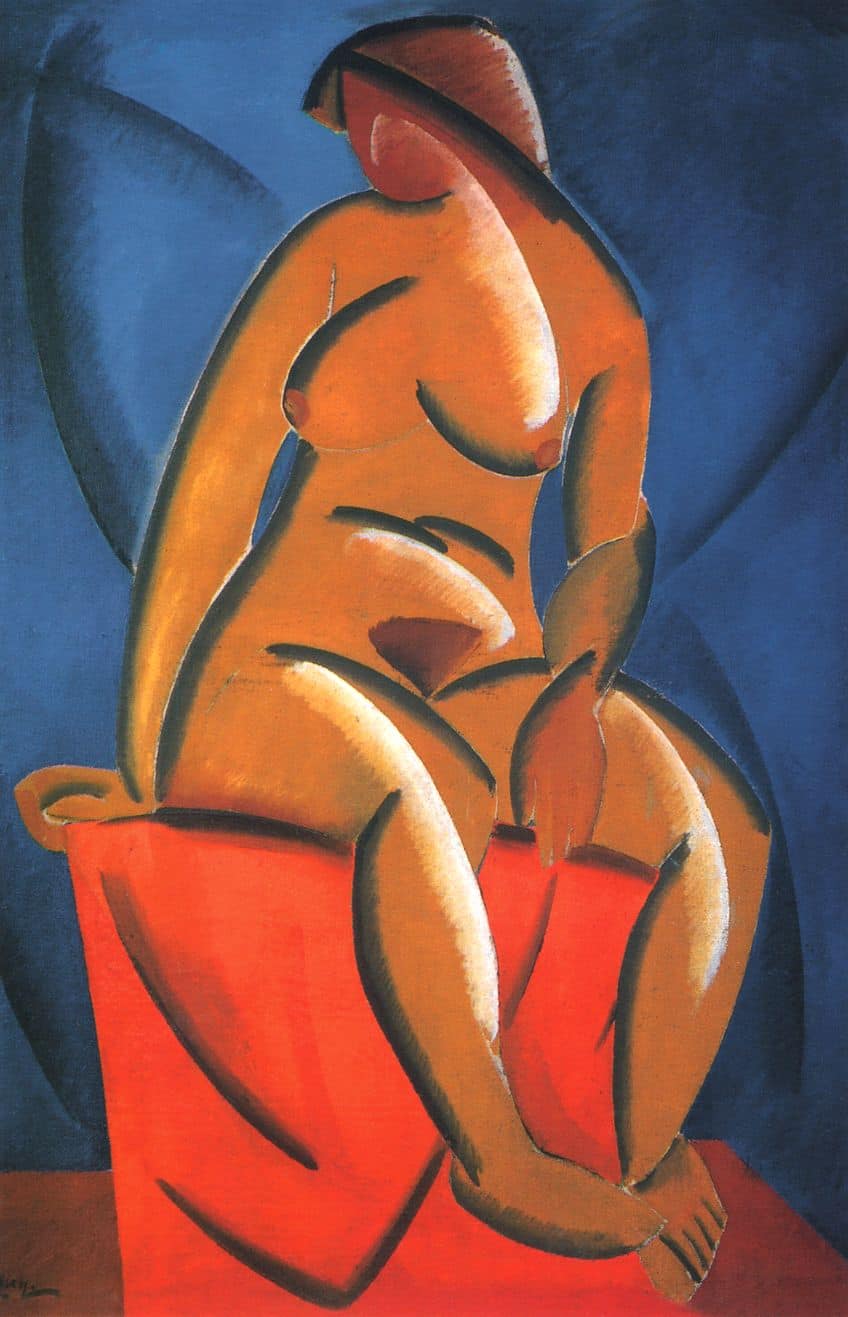

The painter, sculptor, graphic designer, and photographer Aleksandr Rodchenko had been a student and assistant to Vladimir Tatlin and is considered one of the founders of the Constructivism art movement. Like many Russian avant-garde artists, Rodchenko had experimented with Cubism and Futurism in his investigation of form and space. The advent of science, technology, and industry brought dynamism to modern life that inspired Russian artists to transform their notions of the artmaking process.

Rodchenko’s abstract oil on canvas painting Dance, an Objectless Composition (1915) features a dynamic tangle of colored energy with seemingly pulsating facets, planes, and segments. While this work is exemplary of the Cubist influence in Rodchenko’s work, it would serve as a foundation for even more daring explorations. From Tatlin, Rodchenko had learned to make art that was not just beautiful, but utilitarian. His future work would activate space and his objects would no longer be limited to their static form.

While Rodchenko’s Non-Objective Painting no. 80 (Black on Black) (1918) is a clear response to Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915) paintings, it represented an opposing ideal. Though Malevich’s Black Square represented the common goal of reaching absolute non-objectivity, Suprematism had mystical and transcendental ambitions. With this series of paintings, Rodchenko challenged the Suprematist notion of infinite space by amplifying his use of materials in his Black on Black paintings.

Rodchenko designed The Workers Club (1925) work for the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. This work epitomizes the utility and multi-functional aspects of Rodchenko’s designs. The Workers’ Club is constructed mainly from wood which was a practical choice as that material was readily and cheaply available at the time. However, the wood was painted white, red, gray, and black to appear more industrial than organic. This color scheme is also associated with the Russian Revolution.

In its rational and spare design, The Workers Club was a visual proclamation of patriotism and a proud promotion of Communism.

The rectangular space was intended to be truly functional with spaces for reading, learning, entertainment, and even playing chess. The Workers’ Club was Rodchenko’s attempt to contribute to the creation of a new society. The entire space serves as a symbol for the revolution including a prominent portrait of Russia’s then-recently deceased leader Vladimir Lenin.

But this work’s aims are not purely political as it pushes the Constructivist agenda forward with a quiet dynamism. It is noted for its utilitarian aesthetic. The wood in The Workers’ Club is fashioned into basic geometric forms and planes like circles or triangles. There is a rectangular plank at the back of the semicircular seat and two triangular wedges run along the base of the table. The structure is built to seat as many people as possible while supporting the readers’ feet.

While the innovative design is minimal to its core, there is also a dynamic sense of mobility in this work. There is a collapsible display board and a slanted section on the table that flips up to create more reading space. This economization of space through adjustable parts speaks to the artist’s desire to maximize the useability of The Workers’ Club.

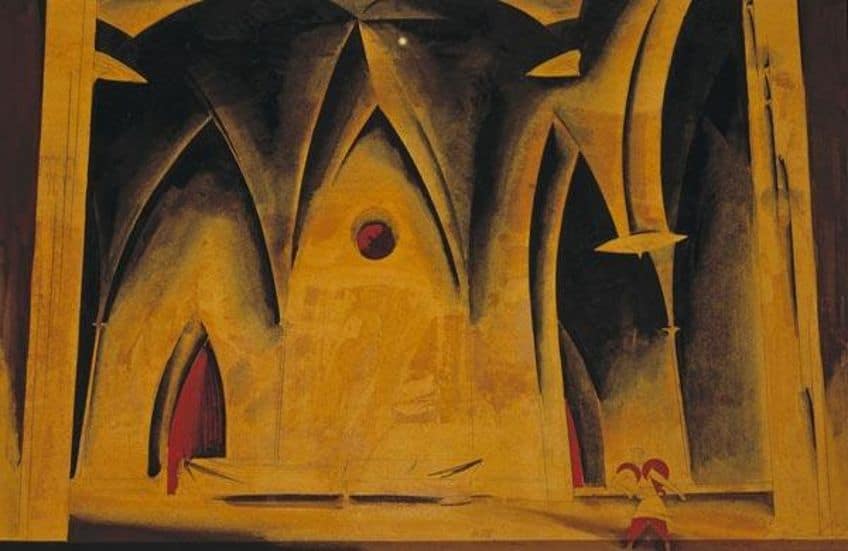

The Influence of Constructivism Graphic Design

Russian Constructivism announced itself as the death of painting. Rather than produce art for art’s sake, Constructivism artists focused on producing art objects that could be functional in everyday life. For this reason, typography and graphic design became essential forms of Constructivism art. Mostly Constructivism graphic design showed up in posters for various things like theatrical plays, cinema, and political propaganda. As such Constructivism graphic design was perfectly paired with photography and advertising.

Many of the Bolsheviks were illiterate therefore Constructivism graphic design became useful for its ability to convey clear, concise messaging. These powerful messages were conveyed through typography, graphic images, photography, or collage. The typographic aspects of Constructivism graphic design were bold yet basic to increase accessibility. Constructivists like Lissitzky and Rodchenko were known for their book designs, Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg were known for their geometric and brightly colored posters, and Valentina Kulagina and Gustav Klutsis were recognized for their photomontage art. As soon as it was supplanted by Socialist Realism, there was a revival of popular interest in Russian Constructivism. Constructivism graphic design became a huge influence on the global history of graphic design.

Radical designers and influential design companies were inspired by constructivist principles which have affected the look of mass-produced objects.

Constructivism in Summary

The Constructivism art movement was incredibly widespread and influential with progressive artists and designers across Europe. It affected major modern art movements of the 20th century such as Bauhaus, De Stijl, and Minimalism. Constructivism included painting and sculpture, but it was not limited to the visual arts. It was literary, but it also influenced modern architecture, graphic, interior, and industrial design, theater, dance, fashion, film fashion, and to some extent even music.

By the mid-1920s, Russian Constructivism was already facing its decline, partly due to the Communist Party’s increasing hostility towards avant-garde art. The Bolshevik regime endeavored to replace Constructivism with Socialist Realism, a movement that could thus not have emerged without the precedent of Russian Constructivism. Indeed, the mark had already been made and Constructivism had become an indelible force in the art history canon. To this day, elements of Russian Constructivism can be seen in visual aspects of everyday life. Constructivism art was popular because it reflected everyday life and demonstrated the ideals of the time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Suprematism and Constructivism?

Malevich and Rodchenko both sought to use art to attain freedom. However, they had differing notions of freedom and utopia. For Malevich, freedom entailed spiritual enlightenment. His ideas were devoid of any political or material motive, whereas artists like Rodchenko sought freedom from traditional norms through their logical use of industrial materials and geometric shapes, which were lathered in political overtones.

Was Constructivism Scientific?

Yes. Einstein’s scientific theories of space and time were an essential inspiration for constructivism. By establishing that there was a fourth dimension of time separate from the third dimension of space, Einstein sent shock waves through the world. This revelation of time and space as nonlinear caused avant-garde artists to move away from rigid symbolism and conventions of art history, opting for an experimental aesthetic that mirrored their realities.

Was Constructivism Art Only in Russia?

No. Constructivism influenced modern masters of Europe, Latin America, and Australia. During the 1930s and 1940s, Naum Gabo developed an English version of Constructivism. After World War I, the style was adopted by artists, designers, and architects, such as John McHale and Victor Pasmore. Oscar Niemeyer, Manuel Rendón, and Joaquín Torres García helped spread it throughout the rest of Europe and Latin America. Figurative Constructivism emerged in Cologne in the late 1920s.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Constructivism Art – Discover the Modern Soviet Movement.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 19, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/constructivism-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 19 October). Constructivism Art – Discover the Modern Soviet Movement. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/constructivism-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Constructivism Art – Discover the Modern Soviet Movement.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 19, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/constructivism-art/.