Dutch Golden Age – The Best of 16th-Century Dutch Art

Time travel with us to the 16th-century Golden Age in the Netherlands, where there were just as many moments of controversy and artistic growth as one might imagine. It is no secret that the Dutch Golden Age produced some of the world’s greatest master artists, however, many do not recognize the context or are aware of the key aspects of this art period that created talents like Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and Johannes Vermeer. In this article, we will examine the history and culture of the Dutch Golden Age, including a few artworks that you will find fascinating. Keep reading to learn more about the Dutch Golden Age!

The Golden Age in the Netherlands

The history of the Dutch Republic and its large-scale economic growth plan was implemented between 1588 and 1672, marked by the expansion of Dutch power across trade, art, science, and militarism. This period was known as the Dutch Golden Age, which was not built in a day. Rather, this era was marked by 80 years of war, which only ended around 1648, along with slavery, colonization, and expensive conflicts between the Franco-Dutch War and the Spanish Succession. How did they recover? According to the historian K. W. Swart, it was a “Dutch Miracle”.

The term “Golden Age” originated as de Gouden Eeuw and was first used in the Dutch language around the mid-16th century. The term emerged from translations of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and is an age-old concept that can also be traced to Latin literature. In European art history, the Golden Age has been used to emphasize a period of political, social, intellectual, artistic, and social developments that transformed various aspects of society and is usually presented as something “lost”, that one must aim to “strive for” once again. During the period when the term “Golden Age” surfaced, the Netherlands faced a civil war. The Netherlands was previously known as the Seventeen Provinces and was engaged in a long-standing conflict with the Spanish Habsburgs.

The Golden Age in the Netherlands was an era marked by cultural and economic boom owed to many factors in the 17th century.

From refugees fleeing Habsburg’s territories and Catholic rule to cross-migrations of artists and scholars arriving in the Netherlands from the Iberian Peninsula, there is much to learn about the context of the Golden Age. At the forefront of this period was Dutch nationalism, which aided the narratives of the Golden Age and leveraged it to strengthen the collective identity of the Dutch people. Curator Tom van der Molen analyzed the use of the term “Golden Age” to provide perspective on the sense of nationalism and collective stamina of Dutch society. He noted that the term was rarely found in print media across the 20th century, however, since the 1990s, the term hit peak usage. The popularity of the term was inextricably linked to the rise of nationalism and populism in the Netherlands, marked during the early 2000s. Interestingly enough, the term was also used more often in non-Dutch literature and has been a useful political and marketing point for a few.

The Emergence of Golden Age Culture and Prosperity

The Golden Age in the Netherlands can also be identified as the Dutch Renaissance, which emerged with the founding of the Dutch Republic shortly after 1579 and ended around the outbreak of the French invasion known as Rampjaar in 1672. The Dutch Republic had already set into motion their system to gain global economic power with the establishment of the multinational corporation Dutch East India Company in 1602. The company enabled the development of the first modern stock exchange and through dealings with Asia, grew its empire to become the largest commercial enterprise of the century.

Of the many sources of wealth and economic gain was the importation of spices, which birthed the word “peperduur”, as a reference for something that was as costly as pepper and which marked the pricey costs of spices at the time. The Bank of Amsterdam was only set up in 1609 to manage the finances brought in by trade. The Republic also traded with Poland and the Baltic states, which accumulated resources in bulk and became known as the “Mothertrade” since the goods were stockpiled in Amsterdam. This stockpiling was seen as essential to the economy since it was common in the 17th century for cities to receive bad harvests and face the repercussions of being unprepared. While areas like England and France saw such repercussions and shortages, the Dutch were equipped to make a greater profit.

World Trade, Colonization, and Slavery

Along with the immense success of the spice trade, the Republic was also able to expand its power and influence after capturing a larger colonial empire, thus making England somewhat jealous over the power trip of the Dutch, and resulting in the Anglo-Dutch wars. In 1621, an officer of the Dutch East India Company known as Jan Pieterszoon Coen led the conquests of the Banda Islands. Most conquests in history involved the mass murder of people and in the Banda Islands, the Dutch were intent on amassing their wealth to secure nutmeg, which was lucrative on these islands.

The Dutch also colonized Brazil and succeeded for a short period taking over the region between the Amazon’s mouth and the São Francisco river.

Other countries colonized by the Dutch include Bonaire, Aruba, and Curaçao. Further conquests with the Portuguese resulted in the Republic’s deeper involvement with the transatlantic slave trade, setting up the routes for slavery throughout the Caribbean Islands, Brazil, Ghana, and Elmina. Angola was conquered by an admiral of the Dutch West India Company, Cornelis Jol, in 1641 followed by more than 550,000 people caught up in the slave trade and shipped to the United States. It goes without further stating that the success of the Dutch economy was largely reliant on the slave trade during the Golden Age, primarily for their dispensability as a labor force.

Local Cultures in the Dutch Golden Age

With the influx of sugar, spice, and foreign fruits into the country, there was also a rise in the consumption of goods like coffee and tea, often served with marzipan and other sweet treats. Middle-class citizens still had access to meals that comprised diverse nutrients and foods, while wealthier citizens indulged in haute cuisine. The development of Dutch culture was at its all-time high in the Golden Age, most notably in the arts, sciences, and literature. The population was primarily Calvinistic and did not fully embrace styles promoted by the Baroque movement for too long. Throughout the Western provinces, the cultural driving force was citizenry, most notably in Holland and to a lesser degree in Utrecht and Zeeland. Wealthy aristocrats also became art patrons to artists in other countries due to their position and location.

Other key cultural hubs included town militia and the chambers of rhetoric, the latter of which was constructed for policing and defense but was also a common gathering place for those who were well-off. The chambers of rhetoric were established in the Low Countries and members of these societies were known as “Rederijkers”. Many wealthy groups also founded mini-social collectives to foster literary activities, including local contests, poetry, and dramas, which became a source of city pride and a way for people to contribute to the “Dutch Renaissance”.

The Influences of Religion and Wealth

One of the most important aspects to examine when unpacking the Dutch Golden Age, especially in terms of the influences on its visual art and stylistic preferences of the time, is to review the influences of religion and wealth on the cultural development of societies and artistic groups from this era. Calvinism played a key role in shaping the existing dynamics of the Dutch Golden Age since it was the official religion of the Dutch Republic. Calvinism greatly emphasized strict religious and moral principles and was relatively tolerant towards the social and economic benefits that were enjoyed by the Protestants from neighboring states. Cities like Utrecht emerged from a Catholic background, however, distanced themselves from the luxury and prosperity of the Golden Age.

There were disputes between Calvinists and Protestants, as well as the permissive Remonstrants, who advocated for freedom of conscience by denying any forms of “predestination”.

The diversity of sects in the Golden Age is one to be acknowledged since there were also groups that considered religion impractical. Tolerance, however, was fostered by the influence of the Renaissance ideal of Humanism through figures like Desiderius Erasmus. During the 80-year conflict against Spain, the role of religion was placed into question and focused on the complexities of upholding tolerance towards Catholic people. At the time, finances and wealth were being used by Catholics to purchase privileges for holding private ceremonies, which diffused and somewhat overcame intolerant sentiments. The different sects remained within their sections in the different towns, which was also best highlighted by the famous Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer, who was a Catholic and chose to remain in the Papist corner of Delft. The Dutch Republic also attracted religious refugees such as the French Huguenots and the Jewish merchants from Portugal after 1685, which contributed to a “relatively” tolerant religious atmosphere.

The Impact of Art Patrons in the Dutch Golden Age

Crucial to the artistic successes of the Dutch Golden Age were the roles and impact of the art patrons and wealthy merchants, who helped foster vibrant cultural landscapes in the 17th century. The prosperity of the Dutch Republic was fueled not only by its colonial ventures, trade, and commerce but also by the merchant class. Wealthy individuals transformed into enthusiastic and passionate art patrons who contributed to the development of various art forms, including literature and painting. Art patrons commissioned artworks to reflect their social status and depict scenes from daily life to convey their personal artistic tastes. Artists who were frequently commissioned by affluent patrons included Frans Hals, Johannes Vermeer, and Rembrandt, who are now widely recognized for their many iconic representations of the Dutch Golden Age.

One of the most enduring functions of art in the Dutch Golden Age, and somewhat in the contemporary era, is the symbolism given to artwork and art collections, as a prominent rank in social status and display of wealth. Many merchant families sought to improve their prestige in society by amassing large art collections that were usually displayed in extravagant homes. These collections became a source of pride and a homage to the prosperity of the owner. Apart from the visual arts, art patrons also paid attention to literature, which saw a rise in the merchant class encouraging a literate society that valued cultural and educational development. Poets, writers, and playwrights were sponsored by art patrons to contribute to Dutch literature during the Dutch Golden Age. The establishment of cultural institutions also enabled the construction of guilds, theaters, and art academies to provide hubs and institutions for intellectuals, writers, and artists to unite, share ideas, and collaborate. These types of cultural exchange centers also promoted the intellectual development of the Dutch Republic.

Art was also a means of beautifying public spaces, which meant that public squares, civic buildings, and canals were often seen as opportunities to express literary and artistic developments alongside architecture while promoting collaboration and boosting a city’s status.

Architecture in the Dutch Golden Age

Among some of the most renowned architects from the Dutch Golden Age include figures like Jacob van Campen, Lieven de Key, Pieter Post, Philips Vingboons, and Hendrick de Keyser. During the Dutch Golden Age, architecture started to rapidly expand in alignment with the thriving economy. Dutch architecture saw the construction of new storehouses and town halls, as well as new homes built by successful merchants who wished to upgrade their public social status. Many cities also built new canals mainly for transport and defense. Since 1595, there were also numerous commissions for reformed churches, many of which remain as historical landmarks today.

For architectural embellishments, wealthier merchants decorated their homes with an ornamental façade, while those who lived in the countryside built new castles and other elaborate residences, however, the majority of homes in the countryside did not survive. During the 17th century, Gothic architecture was very much prevalent, however, it was combined with styles influenced by the Renaissance and French Classicism. In French Classicism, architecture saw the integration of vertical elements with a reduction in ornamentation. Architects of this style preferred to use natural stones as opposed to bricks. This stylistic shift was known as society’s shift toward sobriety and architecture, moving away from the more ornamental and lavish forms of presenting one’s home or city landmark.

By the 1670s, homes were mostly decorated with pillars on either side of the entrance and even a balcony above it, as a simple gesture to this newfound architectural sobriety.

Visual Art in the Dutch Golden Age

Now that you have a better contextual understanding of the political and economic climate of the Dutch Golden Age in the Netherlands and other Dutch cities, we will review some of the most prominent art forms and a few examples of key artists who contributed to the development of the visual arts. We will also take a look at the influence of science on Dutch art after this segment.

Painting

To track the development of painting in the Dutch Golden Age, one can summarize the larger artistic shift as a departure from traditional artistic norms. Most Dutch artists embraced techniques promoted under the Baroque art movement, such as Caravaggism and Naturalism. However, the Dutch Golden Age also produced artists who were experts in championing subjects such as landscape, still-life, and genre painting. While the rest of Europe focused on history painting, the Dutch Republic saw an opportunity to popularize scenes of everyday life.

This contemporary shift was motivated by the growing number of wealthy middle-class and mercantile patrons, whose preferences had a mass influence on the art market.

Secular themes also flourished in the absence of Counter-Reformation church patrons, which led to the development of many genre paintings depicting seascapes, daily activities, and landscapes. One of the most prominent features of Dutch Baroque painting was the emergence of large group portraits, which were commissioned by civic and militia guilds. Examples of this can be seen in Rembrandt’s portfolio with his iconic painting The Night Watch (1642). Ostentatious still-life, also known as pronkstilleven was another important genre in the Dutch golden age that emerged in Antwerp and embraced the intricate opulence of regular objects.

Elements portrayed in pronkstilleven paintings included dead game, fruits, various daily objects, flowers, and living subjects. Prominent painters from this period included Johannes Vermeer, who was widely celebrated for his genre paintings. Other painters who contributed to the resurrection of portraiture included Frans Hals and Jacob van Ruisdael. Additional movements and styles that were born from the Dutch Golden Age include Utrecht Caravaggism, Harlem Mannerism, Leiden fijnschilders, Dutch Classicism, and the School of Delft, which all contributed to the evolution of painting in the 17th century.

Sculpture

While painting may have been the highlight of the Dutch Golden Age, the demand for sculpture was not as one might expect from avid patrons. Sculptures seemed to allude to Protestant churches, which was a collective stance taken by the sect in objection to the Roman Catholic church and their veneration of statues in the Reformation. This decreased the demand for sculpture, and thus the development of innovative sculptural styles was significantly slowed down. A fraction of nobles from the Dutch Republic did, however, play a role in the creation of Golden Age sculptures and found their way across different contexts, in government buildings and embellishments for private residences or churches. Sculptures were largely produced as grave monuments and commissioned for portrait busts, which made up the greater demand for sculpture.

A pivotal Golden Age sculptor was Hendrick de Keyser, whose influence was noted far and wide, along with other 1650s and 1660s sculptors like Artus I Quellinus and Rombout Verhulst, who contributed to the decorative sculptures at Amsterdam’s city hall, now known as the Royal Palace.

Famous Artworks from the Dutch Golden Age

In visual art, Dutch painters often used genres like landscape painting to relay moralistic symbols that reflected their culture’s ideologies and values of the era. A few artists were also able to collaborate with professionals from other fields like natural science and botany, while embarking on trips to colonized countries to seek artistic inspiration. Later on, such artworks were also used as Dutch propaganda to emphasize the dominion of the Republic over the West. Other interesting stylistic developments in painting included trompe l’oeil in genre scenes, allegorical meanings and symbols in idealized interior scenes, and self-determination. Below, we will dive into a few fascinating examples of artwork from the Dutch Golden Age to offer you visual insight into the different approaches of prevailing Dutch artists.

Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds, and Pretzels (1615) by Clara Peeters

| Artist Name | Clara Peeters (1594 – c. after 1657) |

| Date | 1615 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Dimensions (cm) | 34.5 x 49.5 |

| Where It Is Housed | Mauritshuis, Den Haag, the Netherlands |

Clara Peeters was among the most recognized female artists from the Dutch Golden Age, whose signature still-life paintings captured the attention of food lovers and earned her many followers in the Northern Netherlands. The genre of still-life thrived in the Republic due to the condemnation of the imagery used by Catholics. In Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds, and Pretzels, one can spot a delectable spread of figs and cheeses alongside many goods of luxury, from a Chinese dish to a Venetian glass. Antwerp-based artist Clara Peeters was among the first painters of her genre to lead food still-life pieces into popularity. One can also spot the artist’s self-portrait on the pewter lid of the earthenware jug, where she is depicted with a white cap.

This form of still-life was known as “banketje”, which translates to “banquet” in Dutch. Peeters’ insertion of a self-portrait follows the example of the painter Jan van Eyck, who also embedded his image in the renowned Arnolfini Portrait (1434).

It is also equally important to tease out the role of women in society and art during the Dutch Golden Age since there are few examples of women in painting from this era who received as much recognition as their male contemporaries. The 17th century had assigned mostly domestic roles to women, from home supervision to needlework and cooking, which emphasized the woman’s role in a household while men would occupy a small study to conduct business. The management of one’s home reflected the Dutch Republic such that a household that was run smoothly indicated the social status and stability of the owner. Dutch culture, at the time, viewed the home as a refuge from the “immorality” of the world, which was also reflected in the art. Many Dutch paintings of women also showcase their societal roles as engaged in courtship or idealized scenarios of women in gardens, attending music lessons, or reading love letters. Such ideals, on the other hand, did not reflect the truth of society in Petrarchian poetry and genre painting.

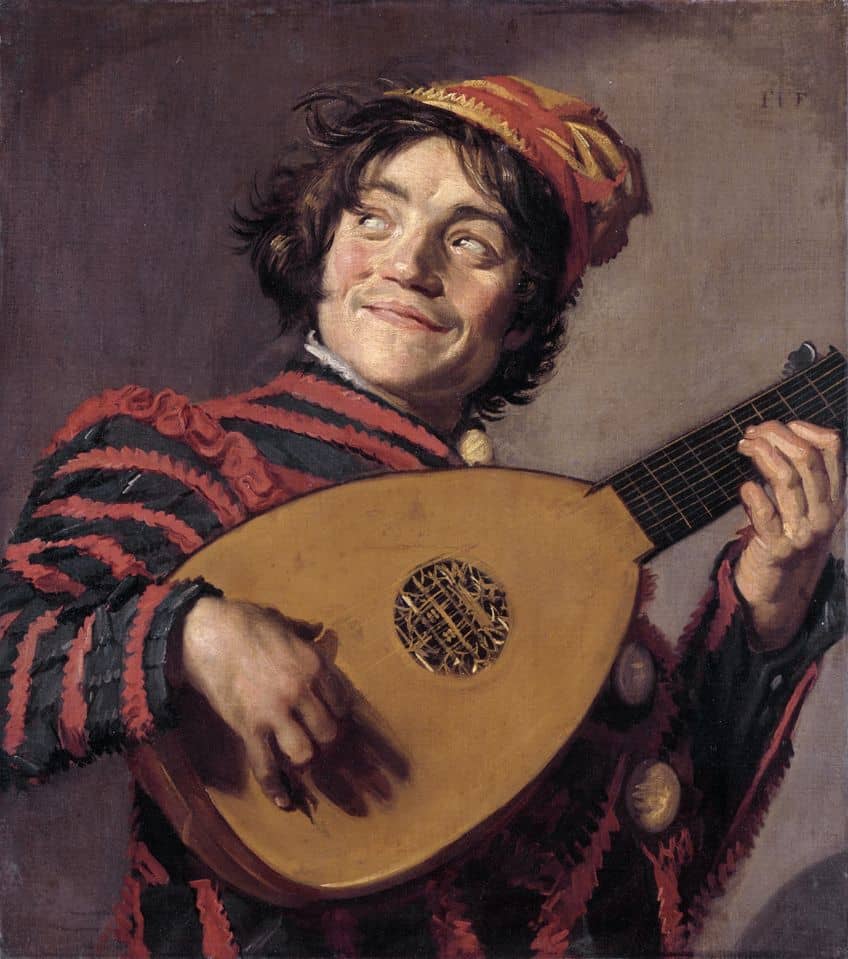

The Lute Player (1623) by Frans Hals

| Artist Name | Frans Hals the Elder (1582 – 1666) |

| Date | 1623 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 70 x 62 |

| Where It Is Housed | Musée du Louvre, Paris, France |

Housed at the Louvre Museum in Paris, The Lute Player is a famous oil portrait from the Dutch Golden Age that was created by group portrait painter and genre scene artist Frans Hals in 1623. The Haarlem-based painter portrayed a lute musician in the rough style using free and energetic brush strokes. The portrait is a gleeful and playful representation of a musician.

Coupled with the loose brush strokes, it influenced many artists of the later Realism movement, including Robert Henri and the French Impressionists.

Brazilian Landscape (1667) by Frans Post

| Artist Name | Frans Janszoon Post (1612 – 1680) |

| Date | 1667 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 50 x 69 |

| Where It Is Housed | Mauritshuis, Den Haag, the Netherlands |

Colonial landscapes such as Brazilian Landscape by Frans Post were a unique genre by Dutch Golden Age artists that traveled to colonized lands to bring back visual snapshots, which can be viewed as “victories” that boosted national pride. Frans Post created this landscape in 1667, which may have been created from a sketch or second trip to Brazil since his earlier visit between 1637 and 1644. Post was also recognized as a Haarlem painter who embarked on the trip along with scientists and other artists selected by the colonies’ governor general, Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen. At the time, Post was only 24 years of age and was supported by the general. In the 1630s, the Dutch West India Company overthrew many Spanish and Portuguese colonies, which gave them access to sugar cane plantations.

Remember that sugar was a hot commodity at the time that raked in high prices across the European market. Post stayed on the northeastern coast and produced a first series of 18 works portraying the strategic sites indicated by the general. While only several of these works remain, these colonial landscapes offer one a unique and colonist viewpoint into the power of such landscapes and the drive for artistic conquering that Dutch art patrons wished to capture. Nassau-Siegen exhibited Post’s paintings in celebration of his accomplishments for the Republic, showcasing them in The Hague and gifting a few to European leaders in exchange for political benefits.

The Dutch Golden Age in art resulted in many fascinating artworks and styles that reflected the culture and contextual developments of the 17th century within the Netherlands and other cities. While the great masters have emerged from a chaotic political climate and problematic colonialist system, one can reflect on such artworks and how art from other regions at the time also mirrored or challenged the styles presented in the Dutch Golden Age. By understanding the historical background of some of art’s most influential eras, one can gain a better perspective of the context in which these artworks were produced.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Dutch Golden Age?

The famous art period known as the Dutch Golden Age was an era of artistic, cultural, and scientific development in the Netherlands, which was largely aided by the expansion of Dutch conquests and colonial power. This period in Dutch history coincided with the slave trade and spice trade, which contributed to the economic growth of the Netherlands.

When Did the Dutch Golden Age Start?

The Golden Age in the Netherlands was marked by the establishment of the Dutch Republic in 1588, and lasted until 1672.

Who Were the Most Famous Painters of the Dutch Golden Age?

Among the most recognized figures in painting during the Dutch Golden Age were Frans Hals, Judith Leyster, Jan Steen, Maria van Oosterwijck, Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, Sara van Baalbergen, Gerrit Dou, Clara Peeters, and Pieter de Hooch.

What Were the Dominant Art Styles of the Dutch Golden Age?

In the Golden Age of the Netherlands, the most prominent art styles included floral still-life paintings, genre paintings, portraits, maritime art, and landscapes. These were developed alongside history painting, which was then practiced across Europe. In Dutch art and architecture, the Baroque and French Classicism styles also prevailed at certain points in the 17th century. Utrecht Caravaggism and Caravaggio’s use of tenebrism also strongly influenced many painters who embraced dramatic and high contrast spotlight features in their paintings.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Dutch Golden Age – The Best of 16th-Century Dutch Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. January 7, 2024. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/dutch-golden-age/

Anthony, J. (2024, 7 January). Dutch Golden Age – The Best of 16th-Century Dutch Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/dutch-golden-age/

Anthony, Jordan. “Dutch Golden Age – The Best of 16th-Century Dutch Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, January 7, 2024. https://artfilemagazine.com/dutch-golden-age/.