Fauvism Art – Creating With Pure Form and Bright Colors

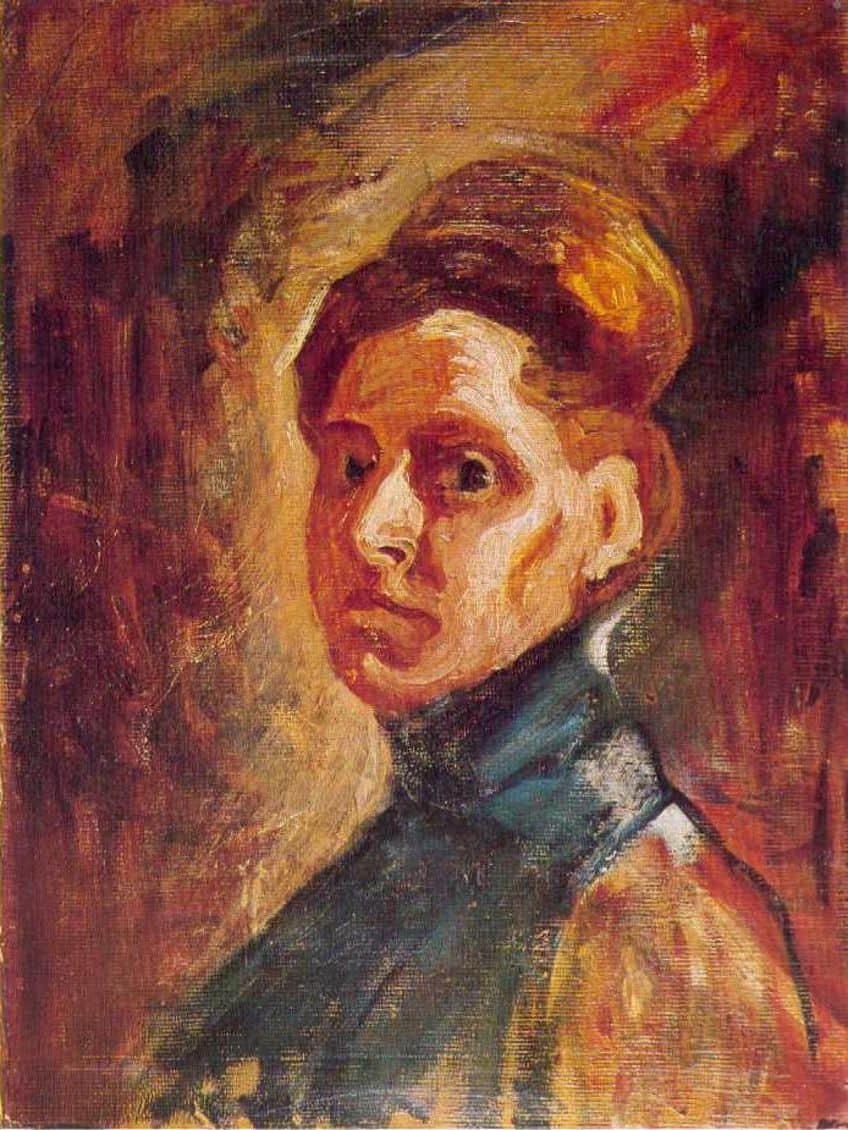

What is Fauvism art? Inspired by the works of Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat, the Fauve movement was the first modern art movement of the 20th century. The Fauves were a group of loosely affiliated French artists who shared many of the same passions and interests. A number of the Fauvism artists, such as Albert Marquet, Henri Matisse, and Georges Rouault, were formerly students of Gustave Moreau, the renowned symbolist artist, and appreciated his focus on personal expression.

An Exploration of Fauvism Art

The Fauvists were united in their utilization of intense colors as a medium for representing space and light and for redefining pure form and color as a way of conveying the emotional state of the artist. Because of this, Fauvism paintings are often considered to be significant precursors to Expressionism, Cubism, and a reference for subsequent modes of abstraction. One of the Fauvist’s most significant contributions to art was their intention to remove colors from their representational and descriptive function so that they could freely exist on the surface independently from the other elements.

Without trying to emulate the natural world, colors could be used to establish the structure in the Fauves’ artworks or project a certain feeling or mood. Achieving an overall balance within a composition was one of the primary concerns of Fauvism artists. The artists of the Fauve movement applied saturated colors and simplified forms, which made one aware of the canvas’s inherent flatness, and how every element plays a particular function within the pictorial space. Fauvism paintings were meant to leave an impression of visual unification, but most significantly, the Fauvists valued the freedom of individual expression.

The Fauvism artists’ emotional reaction to nature as well as his artistic intuition were valued more than the theories of academia.

The History of Fauvism Art

The early 20th-century French Post-Impressionism artists such as Cézanne, Seurat, Paul Gauguin, and Van Gogh were all regarded as Avant-Garde art pioneers. The emergence of the Fauve movement was prompted by their experimentation with the subject matter of their works, paint application techniques, pure color, and expressive lines. Another notable influence on the Fauvist style was Symbolism’s focus on the internal vision of the artist.

Pioneer of the Fauves – Henri Matisse

Fauvism art is typically regarded to have been founded by Henri Matisse. Matisse, like many of his fellow Fauvism artists, took much influence from the teachings of Moreau, who felt that one’s own expression was one of the most essential attributes of a great artist. Pointillism’s visual language, as developed by artists such as Paul Signac, Georges Seurat, and Henri-Edmond Cross, was also a significantly important influence on Matisse when he was younger. Even though it was not a technique that he did not directly apply in his own works, the employment of very small variously colored points of paint to produce an overall harmonious tone deeply intrigued the artist.

Matisse was inspired by this approach to create huge, flat expanses of color with a purposeful, decorative impression and sense of ambiance or mood.

He was also knowledgeable about the Post-Impressionist works of Pierre Bonnard, Paul Gauguin, and Édouard Vuillard, whose incorporation of solid color and design differed from the fleeting appearance of Impressionist paintings. Matisse, after assimilating all of these concepts, discarded the use of the nuanced hues of blended paints and started painting with vibrant colors, straight from the tubes, as a means of expressing emotion. He had been painting outside since the mid-1890s, and his 1898 trips to the south of France and Corsica piqued his interest in recreating the effects of brilliant natural light. In 1904 he spent a summer painting alongside the artists Cross and Signac in Saint-Tropez, where he observed their techniques firsthand.

The Influences of Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain

The two artists Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain met in 1901 and started renting a studio space together in Chatou, one of Paris’ western suburbs around the same years as Matisse’s early experiments with Post-Impressionist approaches. They established their new common interest in directional brushstrokes and vivid color while working together during this period.

Matisse first met Derain in 1899, and a couple of years later was introduced to de Vlaminck by Derain.

He encouraged and supported these two kindred artists as experienced and more accomplished artists, even recommending them to potential dealers. Matisse visited de Vlaminck’s workshop in Chatou in 1905 and was extremely impressed by his utilization of pure colors. Matisse asked Derain to join him at Collioure, a fishing town and port on France’s southern coast, for the summer of 1905. During a pivotal four-month period of collaboration, the two artists worked and refined their styles and approaches, producing several major Fauvism paintings.

The 1905 Salon d’Automne Exhibition

The Salon d’Automne exhibit was hosted in the Grand Palais in Paris later that year. This exhibition featured works by Derain, Matisse, and de Vlaminck, as well as former students of Moreau such as Albert Marquet and Henri Manguin. The Fauvism paintings on exhibit were notable for their use of vibrant, intense color and uninhibited brushwork. Also featured in the exhibit was a somewhat more traditional-looking bust by Albert Marque, and its proximity to the gaudily colored, vigorously produced paintings spurred the reviewer Louis Vauxcelles to characterize the scene as “Donatello amid the wild beasts” (“Donatello parmi les fauves” in French).

The term “Fauves” was thus first used as a term of derision or ridicule, however, it would be one that was ultimately embraced by the movement.

After Fauvism

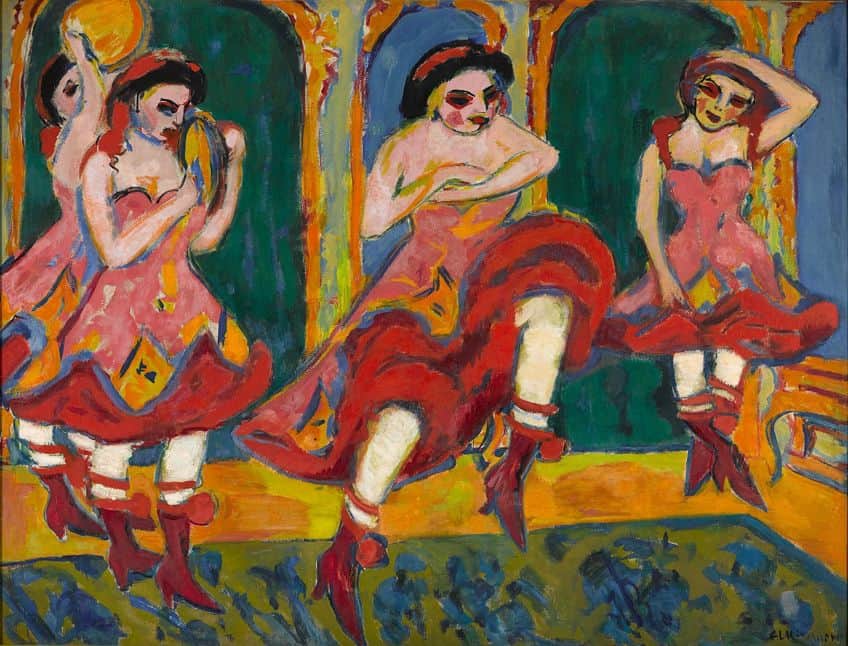

The Fauves’ propensity to distort color and form to portray interior feelings had a great impact on the Expressionists, whose own creative movement lasted far longer and was more unified. The German Expressionists, headed by painters such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, used color in their busy Berlin streetscapes and often grotesque portraits in a similarly uncompromising manner. In some ways, the decline of Fauvism art might also be linked to a renewed interest in the works of Cézanne.

African Artwork

Another noteworthy crossover during this time period was Picasso’s and the Fauves’ interest in African artworks. Matisse traveled to Morocco and returned with new ideas about pattern and color which expressed themselves in paintings like Blue Nude (1907), with their significantly simplified characteristics and angular limbs influenced by African sculptures. This incorporation of non-Western creative inspiration had a great impact on Picasso when he was younger.

He started incorporating Iberian and African masks into his own artwork, including several self-portraits and the renowned Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907).

Cubism and Cézanne

In 1907, a Cézanne exhibit in Paris rekindled interest in the artist’s work, notably his focus on naturalistic structure and order. Georges Braque, for instance, started favoring a more limited color palette, emphasizing the application of scale gradations and subtle colors. This method inspired Braque to cover his paintings with a cluttered yet precisely arranged profusion of forms and shapes as in his artwork Road near L’Estaque (1908), which is an indisputable predecessor to the artist’s establishment of the Cubist style.

Aftermath

By 1908, the Fauves had split up: Braque started producing Cubism with Picasso, Derain temporarily toyed with Cubism, and de Vlaminck darkened his subject matter as well as his color palette. Meanwhile, other members of the Fauve movement, such as Dufy, Marquet, and Rouault, had started to experiment with different techniques. Ultimately, instead of a completely defined school, the Fauves came together for a relatively brief yet crucial period of time. Despite the fact that the Fauvists never created a group manifesto detailing their artistic objectives, Matisse’s Notes of a Painter (1908), formally recognized many of their common interests and priorities, such as their utilization of color as a stand-alone visual element with an emotional impact, their dedication to individual expression and independent intuition, and their reconsideration of composition as pictorial surface.

Even though the group separated, almost as soon as it acquired its infamous moniker, Fauvism art’s theories and iconic pieces would continue to impact the world of art for many years to come.

The Styles and Concepts of Fauvism Art

Despite some initial disapproval from critics, numerous Fauves experienced commercial success after the 1905 Salon d’Automne exhibition. Their work was included in subsequent exhibitions, most significantly at the Salon des Indépendants in 1907, when the primary attraction was a huge area called “The Fauves’ Den”. Georges Rouault, Othon Friesz, Kees van Dongen, Raoul Dufy, and Georges Braque were among the artists that eventually became part of the Fauve movement. During the brief heyday of Fauvism art, these artists traveled together, shared workshops, and readily shared ideas.

The Importance of Color to the Fauvist Artists

All of the Fauvism artists were concerned with color as a method of self-expression. Color combinations were the fundamental theme, form, and movement of their works. Trees could be colored blue, skies could be orange, and faces could be combinations of contrasting colors – the outcome was an entirely distinct creation of the artist’s vision, instead of a true reproduction of the actual physical form.

Furthermore, instead of employing perspectival techniques or draftsmanship, compositional aspects were developed simply through the application of color.

Style and Subject

These painters were less preoccupied with the originality of their subject matter due to their shared interest in expressiveness using form and color. While the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists portrayed scenes of urban, contemporary life, such as cafés, boulevards, and music halls in Paris, the Fauves began with more conventional topics. Their subjects included landscapes, portraits, seascapes, and individuals in interiors, but the aesthetic effect of the color combination took priority over any potential story or meaning. Instead, they utilized their subjects as vessels for acts of painting and observation, using dynamic brushwork and non-naturalistic colors to draw the audience into their inner, creative excursions.

Notable Fauvism Artworks

Fauvism paintings are defined by their utilization of vibrant colors and non-naturalistic brushstrokes. Exaggerated and emotive still lifes, landscapes, and portraits are commonly depicted in Fauvism paintings, with a strong focus on color over form. Here are a few of the most significant Fauvist artworks produced.

Luxe, Calme et Volupte (1904) by Henri Matisse

| Artist | Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) |

| Date Completed | 1904 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 98 x 118 |

| Current Location | Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, France |

In the employment of tiny beads of color to produce a visual frisson, Matisse’s early works clearly demonstrates the artist’s stylistic inspirations, most particularly the Divisionism of Paul Siganc and the Pointillism of Georges Seurat. Matisse’s powerful concentrations of pure color, though, distinguish this piece from these more strict approaches. The yellows, oranges, greens, and other hues all have their own distinct positions on the pictorial plane.

They never quite blend to make the harmonic tone that both Signac and Seurat were renowned for, instead heightening an almost vertiginous effect produced by the vivid dots of color.

Yacht at Le Havre Decorated with Flags (c. 1905) by Raoul Dufy

| Artist | Raoul Dufy (1877 – 1953) |

| Date Completed | c. 1905 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 48 x 65 |

| Current Location | Musée d’art moderne Andre Malraux, Le Havre, France |

Dufy painted various depictions of Le Havre, a port city on the northwest coast of France, in the manner of Eugene Boudin and Claude Monet. This image illustrates multiple ships that are docked against a backdrop of local structures. While the artwork is mostly realistic, Dufy’s disregard for standard perspective and unorthodox painting techniques are avant-garde.

The wharf’s sharp diagonal line, for instance, has a disruptive impact.

The landscape is painted in a simplified notation of fast brushstrokes: small blocks of color for the waterfront architecture, a smattering of little curving dabs for the waves, and rough, truncated strokes for the passing pedestrians’ figures. An assortment of nautical flags dances from the ship’s mast in the middle of the painting, each one a little abstraction of shape and color. Yet, Dufy’s seemingly rough brushwork and the canvas’s naked edges do not distract from the piece; rather, they contribute to an overall feeling of casualness and joviality.

The River Seine at Chatou (1906) by Maurice de Vlaminck

| Artist | Maurice de Vlaminck (1876 – 1958) |

| Date Completed | 1906 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 82 x 102 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

This view represents the Seine as it flows past Chatou, a Parisian suburb wherein Derain and de Vlaminck had a workshop commencing in 1901. De Vlaminck utilized impasto for the artwork, which consists of thick daubs of paint painted straight from the tube, then stroked together in quick sweeps to produce the illusion of movement. He chose a variety of greens and blues for the sky and water, as well as brilliant white accents done in jagged dabs; the two orange and red trees on the left create a vibrant contrast. The overall effect is one of brilliance and pulsating motion; details and traditional perspective are secondary to a sensation of buoyant delight.

“I attempt to paint with my heart and intuition without caring about style”, stated de Vlaminck.

Maria (c. 1907) by Kees van Dongen

| Artist | Kees van Dongen (1877 – 1968) |

| Date Completed | c. 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 64 x 54 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

The Fauve movement had already begun to fracture by 1907. This painting combines elements of the Fauvist style – including the expressive use of unmixed color and visual flatness – with a naturalism that marks a pivotal turning moment in van Dongen’s art. Unlike in some of his other works, the whites of the eyes and the shape of the face are discernible – subtle creases at the borders of her lips accentuate a repose in her features, and the Rembrandtian shadow that crosses her forehead shows that the model is in thought. Her crimson-red clothing emphasizes the drama of her features, which include wide eyes accented with thick black eyeliner, a beautiful pose, upswept black hair, and light skin.

Over the following several years, he would polish this portraiture approach, which was a reaction to Cubism’s extremism and the deconstructive vision already established by Braque and Picasso.

Pinède à Cassis (Landscape) (1907) by André Derain

| Artist | André Derain (1880 – 1954) |

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 54 x 65 |

| Current Location | Musée Cantini, Marseille, France |

Derain famously stated that he uses color to communicate his emotions instead of to mimic nature. Derain utilized sweeping, solitary brushstrokes in this picture, influenced by Divisionist art, to shape the ground and trees of his scene. The colors are non-representational, almost unnatural: the tree trunks are nearly green, and the landscape is abstracted in vivid orange and yellow regions. These hues convey the radiant heat of a Mediterranean summer through their stark contrasts and pulsating brushwork.

Derain focuses the viewer’s eye on this lighting effect and the life energy that seems to permeate every part of the landscape by eschewing spatial depth and chiaroscuro.

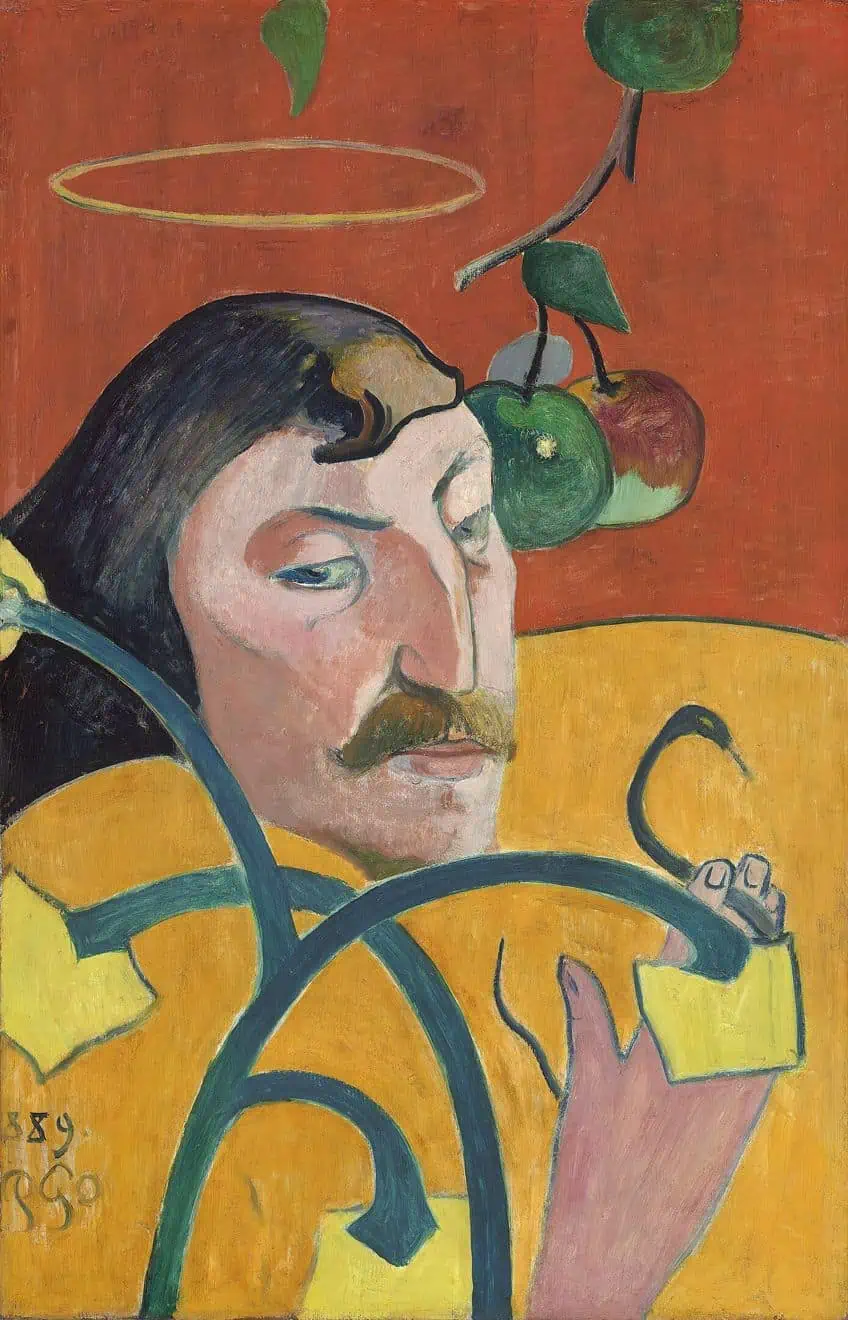

Self Portrait (1907) by Nadežda Petrović

| Artist | Nadežda Petrović (1873 – 1915) |

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unspecified |

| Current Location | National Museum of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia |

This artwork is regarded as a significant example of the Serbian avant-garde movement. The artwork is notable for its vivid use of color and unorthodox brushstrokes, both of which are features of the Fauvist style. Nadežda Petrović was a noted Serbian artist who worked in the early 20th century. She was inspired by the Fauvist style and applied it in her own works, creating bright, colorful canvases with a feeling of vitality and movement. Her artistic output comprises about 300 oils on canvas, around 100 studies and sketches, as well as numerous watercolors. Her paintings are associated with the movements of Secession, Impressionism, and Symbolism, in addition to the Fauve movement.

After her death, her portrait appeared on certain Serbian banknotes.

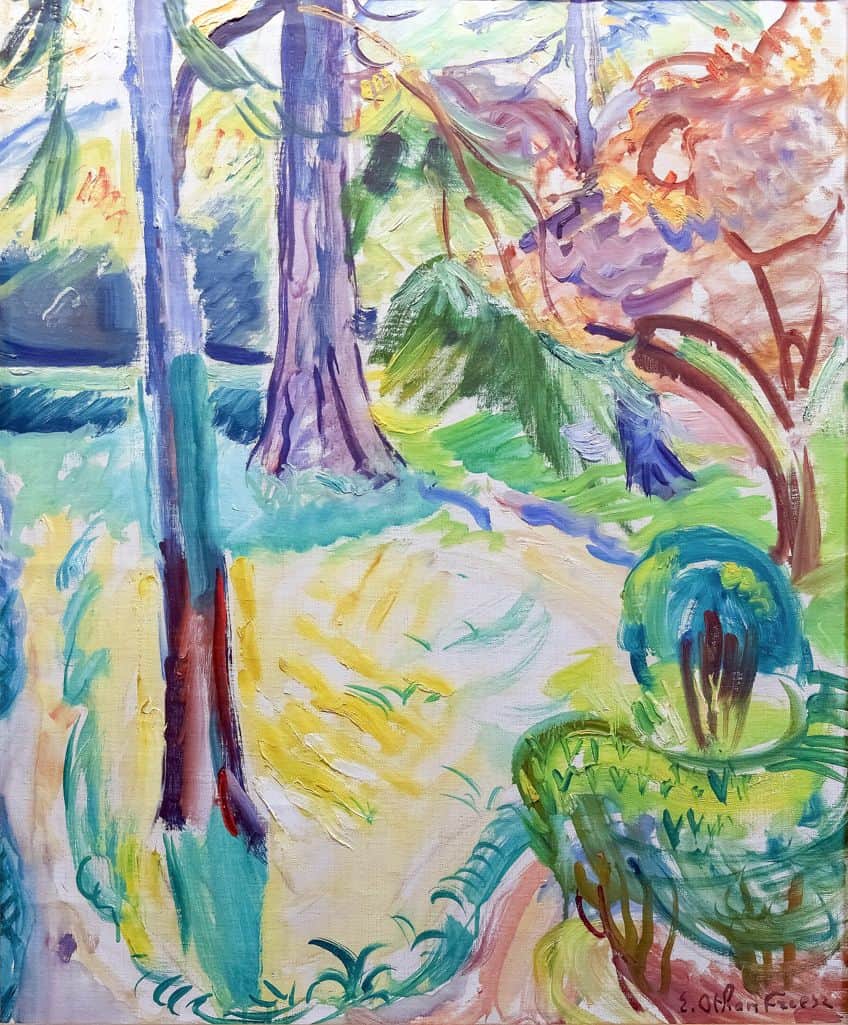

Paysage à La Ciotat (1907) by Othon Friesz

| Artist | Achille Émile Othon Friesz (1879 – 1949) |

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 60 x 72 |

| Current Location | SFMoma, San Francisco, United States |

Othon Friesz, a Le Havre native, traveled to Paris in 1898 to study painting and became a member of the company that also included Rouault, Matisse, Dufy, and Marquet. He regularly traveled in pursuit of landscapes, and a journey to La Ciotat and L’Estaque in southern France with his friend Braque from 1906 to 1907 produced numerous major Fauvism paintings. Friesz employed warm and bright yellow tones for this perspective of the town, which he enhanced with hints of green. Despite being a devout Fauvist for as long as any of his peers, Friesz’s treatment of the canvas was considerably more conventional, his color selections were more intentional, and his painting technique was more systematic.

Friesz used Fauvist color to create an Impressionist-style environment.

Paysage à La Ciotat (1907) by Othon Friesz; Othon Friesz, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Paysage à La Ciotat (1907) by Othon Friesz; Othon Friesz, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the Circus (The Mad Clown) (1907) by Georges Rouault

| Artist | Georges Rouault (1871 – 1958) |

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on Cardboard |

| Dimensions (cm) | 75 x 57 |

| Current Location | The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States |

Rouault, a friend of Matisse and a pupil of Moreau, approached his early Fauvist paintings such as this one with a more melancholy, psychologically perceptive approach. Although he used impasto and rich brushwork like the other Fauvists, he chose darker hues that matched his acute study of human misery. Rouault picked the topic of the circus performer, as did Honoré Daumier and Édouard Manet in the 19th century and his colleague Pablo Picasso in the early 20th century. Rouault was chastised for concentrating on the destitute on society’s outskirts; he also painted prostitutes, nomads, and manual laborers.

His spiritual and creative inclinations eventually led him to depict more scathing depictions of societal inequity and the unscrupulous abuse of power than the other Fauvism artists.

Jeanne Dans Les Fleurs (1907) by Raoul Dufy

| Artist | Raoul Dufy (1877 – 1953) |

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 54 x 64 |

| Current Location | Musée d’art moderne Andre Malraux, Le Havre, France |

This is a wonderful example of Dufy’s Fauvism style: the painting’s subject, a young lady surrounded by flowers, is reduced and abstracted, with brilliant colors and free brushwork generating a feeling of vitality and movement. Dufy created various garden landscapes inspired by his family’s house in Le Havre in the early days of his work, freshly motivated by a visit to the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Yet, this is the only painting from that time period with a human figure. Dufy enjoyed painting landscapes and flowers, as did the Impressionists, but this view of his family’s garden, created in a small, sharply cropped area, was a more emotive art piece.

His ambiguous blending of background and foreground through the contours of the vegetation, his rough brushwork, and his non-naturalistic utilization of colors – even in the skin of Jeanne – exemplify Fauvism’s liberation from figurative aesthetics and its new emphasis on color’s inherent emotional power.

Le Viaduc à L’Estaque (1908) by Georges Braque

| Artist | Georges Braque (1882 – 1963) |

| Date Completed | 1908 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 72 x 59 |

| Current Location | Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France |

Braque depicted the landscapes of L’Estaque in various color palettes between 1905 and 1908. The round arches of the old viaduct link both sides of the scenery, and the foreground is a neatly arranged mass of boxy houses and fervently brushed greenery, revealing Braque’s mixture of Fauvist coloring and simplicity of form with a newly emerging interest in volume and perspective.

This painting foreshadows Braque’s eventual involvement in the creation of Cubism, the 20th century’s next significant contemporary movement.

The Red Studio (1911) by Henri Matisse

| Artist | Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) |

| Date Completed | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 162 x 219 |

| Current Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Matisse deconstructed the traditional divisions between background and foreground and space and figure in this piece. In this artwork, both perspective and color are non-naturalistic: The canvas is a single large expanse of vivid crimson. The delicate, light contours of furnishings and walls are essentially underpainting shown from behind the red, and they defy any typical perspectival framework. Rather, space is compressed and exaggerated, giving the impression that the observer is gazing down into the room from a higher vantage point. While the dramatic use of colors and space is Fauvist, the reduction of shapes and static nature of the artwork speak to Matisse’s developing interest in non-Western influences and eventual involvement with the École de Paris.

Western painters from Courbet to Rembrandt depicted their own studios, but Matisse conveyed his artistic process and inner vision rather than displaying himself at work. It also contains a selection of the artist’s Fauvism paintings, ceramics, and sculptures, a box of pastels, a wine glass, and a potted plant that adds a touch of nature to an interior scene. Certain omissions further emphasize the impression that this “workshop” is a mental state as much as a physical location: there is no defining line in the left back corner of the space, and the grandfather clock lacks hands to measure time.

The Fauvism artists were not intending to shock people; they were merely experimenting, attempting to portray a new way of perceiving that featured pure, vibrant colors. Some of the artists approached their endeavors cerebrally, while others chose not to analyze at all, but the outputs were similar: chunks and dashes of colors not found in nature, contrasted with other artificial colors in an emotional frenzy. Fauvism was not really regarded as a movement since it lacked written instructions or a manifesto, a membership register, or exclusive group exhibits. Rather, it was a group of artists who were only loosely connected and experimented with color in about the same way at approximately the same period. However, despite the short timeframe in which it occurred, the style would end up influencing many of the movements that came after it.

Take a look at our Fauvism webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Fauvism Art?

The term was originally coined when an art critic who had come to view the paintings at the 1905 Salon d’Automne Exhibition accused the art of looking like the work of wild beasts – or Fauves in French. While he had meant it as an insult, the name soon became synonymous with the style and those who produced it. For the Fauves, the use of color was of utmost importance, and they would even use it in its pure and unmixed state, which resulted in very bright and vivid colors.

What Characterizes Fauvism Paintings?

Fauvism artists preferred trying to depict the inner vision more than worrying about naturalistic depictions. That meant that very often, the sky could be a totally unexpected color such as red, or trees could be blue – what was important to them was what the color expressed about their emotional state. Because the Fauves refused to utilize traditional painting techniques to outline shapes, basic forms were required in their compositions. Landscapes or depictions of ordinary life among landscapes were popular subjects for the Fauves. There’s a simple explanation for this: landscapes aren’t too finely detailed and they demand huge splashes of uniform color.

What Influenced Fauvism?

Post-Impressionism was their major influence, as the Fauves likely knew the Post-Impressionists directly or personally. Henri Matisse attributed his discovery of his inner Wild Beast to both Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. The Fauvism artists blended Paul Cézanne’s constructive color planes, Paul Gauguin’s Symbolism, and the clean, vivid colors with which Vincent van Gogh will always be remembered.

What Movements Did Fauvism Art Influence?

Fauvist art had a significant influence on other expressionistic movements, notably Die Brücke and the subsequent Der Blaue Reiter group. More significantly, the vibrant colorization of the Fauves influenced innumerable individual artists in the years thereafter, including Oskar Kokoschka, Max Beckmann, George Baselitz, and Egon Schiele. Many Abstract Expressionists were also influenced by the prioritization of color over form, preferring to create compositions that were driven by intuition and color, instead of trying to accurately depict the natural world in a realistic color palette.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Fauvism Art – Creating With Pure Form and Bright Colors.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 17, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/fauvism-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 17 October). Fauvism Art – Creating With Pure Form and Bright Colors. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/fauvism-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Fauvism Art – Creating With Pure Form and Bright Colors.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 17, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/fauvism-art/.