Mexican Muralism – Discover the Social Importance of Murals

The Mexican Mural movement was established because of the need to encourage patriotism and pride in a nation that was recovering after a revolution. It brought the traditional Mexican art of mural painting back from the legacy of Mexico’s ancient peoples into the modern era as a recognized artistic form with significant social value. Mexican murals were produced in public spaces, which made the art and its messages accessible to all people. Mural painters filled their famous murals with messages about politics, cultural identity, progress, and resistance. Let us learn more about Mexican Muralism and its impact in the article below.

The Significant Impact of Mexican Muralism

Mural painting in Mexico was very impactful as it proved that art did not have to be confined to galleries and museums, and could be used as a viable means of communication in public spaces. This provided Mexican mural painters with ample opportunities that didn’t rely on the art market. These mural painters were aware that a large percentage of the population was illiterate and that visual messages could be transmitted through Mexican murals, instilling a sense of patriotism and pride in the country’s citizens. This was seen as a more effective way of spreading political sentiments than the usual printed pamphlets and advertising. While the early Mexican painters favored socialism, they would develop with time to depict technological advancement, the Industrial Revolution, and capitalism. While the government would often commission mural paintings with a clear message in mind, those within the Mexican Mural movement would often ignore the intended message and fill the works with their own ideas.

The History of Mexican Muralism

The Mexicans have a long history of mural painting that extends back to the pre-Hispanic era with the Olmecs, an ancient civilization that created some of the first known South American painted artworks. Under Hispanic control, Mexican murals served to expose the citizens of the country to the concepts and stories of Catholicism. From that moment onwards, Mexican murals quickly grew into one of the most prevalent art forms in Mexican culture, functioning as a means of expression for people all throughout the nation.

This provided an established platform for politically inspired Mexican artists and contributed to the formation of the Mexican Mural movement.

The Impact of the Mexican Revolution

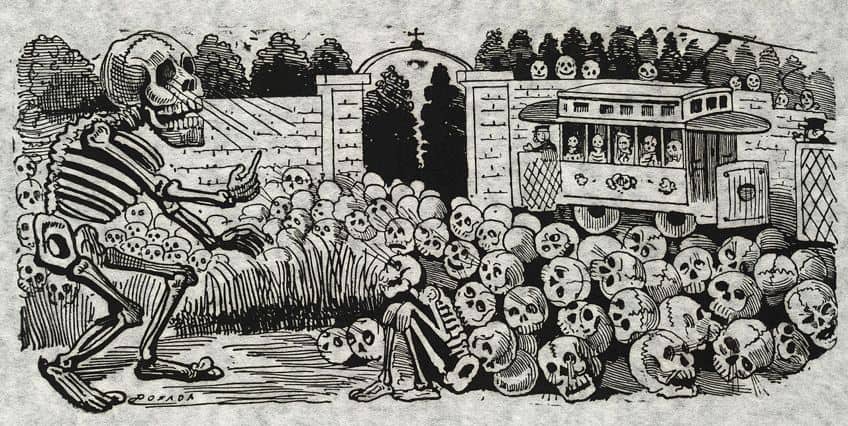

The Mexican Revolution started in 1910 as the country revolted against Porfirio Diaz, the president who ran the country with tyranny. This launched a 10-year civil war, which was headed by a number of charismatic people whose particular political objectives often determined the revolution’s trajectory. These influential individuals socialized with a group of radical intellectuals that included Mexican painters such as Dr. Atl and José Guadalupe Posada.

Dr. Atl published a manifesto in 1906, stating his support of a new Mexican art movement that would represent the realities and concerns of the citizens of Mexico. This manifesto served as a precursor to the Mexican Mural movement, and it was highly lauded by his artistic peers, particularly Diego Rivera. When the Mexican Revolution came to an end, Diaz was deposed and a new government took power. The aim of the new administration was to usher in a new age for Mexico and its newly liberated citizens, and one of the ways it intended to achieve this was through Mexican murals.

Mexican Government Support

The new administration chose to follow Dr. Atl’s lead and commissioned a great number of public artworks in order to endorse the revolutionary principles and to help develop a new Mexican identity. This new identity was founded on the rich historical heritage of Mexico in addition to a sense of steady progress towards the modern era. Most Mexicans could not read at the time, therefore disseminating the new government’s agenda could not be achieved by traditional media like newspapers. Instead, the administration communicated its point through big-scale mural paintings in public areas that were visible to a huge number of people.

The visual appeal of the mural paintings would also help Mexicans adjust to the new government by instilling a feeling of pride in their communities.

These famous murals were often painted with motifs that glorified the Mexican Revolution, evoked the early pre-Hispanic past of Mexico, and promoted the new government’s values. The government of Mexico hired some of the top mural painters of the time to create these famous murals. Some of these painters had spent time abroad in Europe before the revolution and were familiar with the European realism movement, which used painting to portray the plight of the oppressed working masses.

The Big Three Muralists

The Mexican Mural movement was led by José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Diego Rivera, who rose to fame as the “Big Three” around the world. The most well-known of these artists was Diego Rivera. He used Cubism and European Modernism aspects in his work, as well as the vibrant colors of Mexico, to portray his people, especially the working class, as noble people. Orozco had personally participated in the revolution and used European Expressionism to depict humanity’s suffering and the concern of future reliance on technology in a straightforward manner.

Siqueiros was a youthful and daring artist who used innovative materials and techniques to create Mexican murals that often combined concepts of machinery and science to symbolize growth. Despite their differing political objectives, all three men believed that art, as the ultimate form of expression, should be an important element of the post-revolutionary identity of Mexico. They regarded art as an instrument for education and societal improvement. The first efforts of the administration were directed towards commissioning paintings for the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. The institution was an important stepping stone for anybody interested in politics or the intellectual sphere of the country.

Diego Rivera was selected to create a mural called The Creation for the auditorium of this institution and this work helped to lay the foundation for the Mexican Mural movement.

Other Mexican mural painters commissioned by the state to produce murals for the institution include David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Jean Charlot, and Fernando Leal. After the success of Escuela Nacional Preparatoria’s project, there was an explosion of Mexican mural works around the country in the mid-1920s, and the painters involved rapidly achieved worldwide recognition for their distinct styles.

Mexican Muralism in the United States

Mexican Muralism’s influence started spreading towards the end of the 1920s, notably in America. All three of Mexico’s most famous mural painters spent time in the United States after achieving fame in Mexico. This was partially due to fractures appearing in the idealism usually presented in Mexico shortly after the revolution. The government’s statements and conduct no longer matched those of the artists they hired, and whereas the early period of the Mexican Mural movement was defined by the artists’ independence to express themselves, the government progressively wanted to exert influence over the subjects portrayed in the Mexican murals they commissioned.

José Clemente Orozco was asked to create a mural at Pomona College in 1930, announcing the emergence of Mexican Muralism in the United States. Diego Rivera relocated to the United States the same year and received commissions to create mural paintings all throughout America, only to return to Mexico four years later. In 1932, Siqueiros fled Mexico and settled in L.A., where he created numerous famous murals. The arrival of these Mexican mural painters caused a wave of interest in American art, and murals soon became an increasingly popular type of public art in the country.

The Impact of Industry and Religion

Despite its socialist origins, many of the mural painters participating in Mexican Muralism became captivated by the capitalist technological advancements presented by businesses in the United States. Most famously, Diego Rivera created a series of famous murals in Detroit showing individuals collaborating with machines to produce an ideal synthesis of human labor and modern technology.

Other artists, like Siqueiros, regarded technological developments as a double-edged sword, yet Siqueiros was still drawn to industrial images.

Mexico’s dominant religion was Catholicism, which was introduced by Mexico’s former Spanish administration. It was, however, a kind of local Catholicism that integrated iconography and rites from indigenous Mexican faiths. Many mural painters in Mexico saw the blend of Western and indigenous religious practices as something that distinguished Mexican identity, and they investigated it in many of their famous murals.

Later Developments

Mexican Muralism had the greatest impact on art in the Americas. Mexican Muralists such as the “Big Three” visited the United States, which influenced President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Public Works of Art initiative. During the Great Depression, it was meant to offer work for artists and artisans, as well as to produce morale-boosting sculptures and murals for public buildings. It was inspired by the post-revolution Mexican government’s program of public murals and even involved several Mexican painters in the United States. On the other hand, Mexican Muralism impacted the growth of American Social Realism during the years of the Great Depression, when artists started to sympathize with and reflect on the harsh reality of the working class and the wealth divide.

Because of their positions in the United States, these Mexican painters had much more influence. Siqueiros, for instance, taught experimental painting lessons in New York, and one of his pupils was Jackson Pollock, whom he urged to continue with his creative experiments, which became the start of Abstract Expressionism. Pollock, like the Mexican muralists, eschewed the traditional use of the canvas, but instead of abandoning it totally, Pollock started producing wall-sized works and painting on the floor. Mural painting remains a major art style in Mexico and South America, as seen by the emergence of street art initiatives in numerous Central and South American towns.

The Mexican Mural Legacy

The Mexican Mural movement’s fundamental contribution to modern art was the integration of traditional mural painting into mainstream art in the 20th century, particularly as a statement regarding societal ideals or as a means of pushing a political agenda. Its example may have had an influence on Roosevelt’s WPA-sponsored arts programs in the United States throughout the 1930s. Mexican Muralism stood in stark contrast to the move into abstraction followed by many other 20th-century artists from 1930 to 1960. Even at present, more than 100 years after Gerardo Murillo began creating murals, wall paintings may be found in churches, government buildings, and schools throughout the country.

Its fundamental concept, free public art for everybody, influenced New York graffiti artists in the 1970s.

Famous Murals

Mexican Muralism focused on the nation’s pre-European culture and heritage. The famous murals were often political in nature, monumental in scope, and displayed in public settings to foster Mexican pride and patriotism. Let us take a closer look at several famous murals below to gain a better understanding of the importance of these works.

The Creation (1922) by Diego Rivera

| Artist Name | Diego Rivera (1886 – 1957) |

| Date Completed | 1922 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | 365 |

| Location | Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, Mexico City, Mexico |

Rivera’s first government-commissioned painting was selected for the oldest high school in Mexico. Dr. Atl had been asked to produce the mural prior to the Revolution in 1910, and Rivera’s effort was an extension and evolution of Dr. Atl’s revolutionary themes. The composition was influenced in part by the odd curvature of the wall he was hired to cover. The enormous niche in the center houses a pipe organ, and Rivera decorated the resulting arch with a series of figures to the left and right, as well as a symbolic representation of God presiding over the arch’s tight curve.

Adam and Eve are shown as nude Mexicans, staring up at symbolic portrayals of the virtues and arts, along with Catholic saints.

The revered figures had both white complexions and the darker color of indigenous Mexicans. The theme is one of a new multicultural and ethnically harmonious nation emerging from the post-revolutionary era by means of the fusion of contemporary and indigenous ideas. This famous mural represents an important milestone in the Mexican Mural movement, as the artist combines motifs of Italian Renaissance frescoes with a uniquely Mexican style. He ultimately felt, however, that he had taken too much from the Italianate style and intended to produce a more “Mexican” style from then on.

Los Danzantes de Chalma (1922) by Fernando Leal

| Artist Name | Fernando Leal (1896 – 1964) |

| Date Completed | 1922 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unstated |

| Location | Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, Mexico City, Mexico |

Despite not achieving the acclaim of the “big three”, Leal was among the first mural painters asked to adorn the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria due to his passion for portraying the local Mexicans. This famous mural was produced in the Post-Impressionist style, influenced by representations of non-Western people by artists like Paul Gauguin. It represents an incident that Leal heard happened in a Mexican community. The motion caused during a traditional dance of devotion to a statue of the Virgin Mary led to it falling over.

This exposed another little figure of the indigenous Mexican water deity, which had been hidden beneath the Catholic statue.

This, according to the artist, represented the contemporary union of Catholicism and native religion that was fundamental to the Mexican identity. He was permitted to pick the location for his painting in the school, and he chose, unexpectedly, an area of wall above the central stairwell. This area was geometrically challenging, but it was a classic illustration of Mexican Muralism’s desire to take advantage of the particular features of the architecture as a blank slate beyond the typical restrictions of canvases, thereby challenging traditional formats.

The Banquet of the Rich (1924) by José Clemente Orozco

| Artist Name | José Clemente Orozco (1883 – 1949) |

| Date Completed | 1924 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unstated |

| Location | Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, Mexico City, Mexico |

In this piece, we observe Orozco’s unique caricature style, which differed considerably from Rivera’s mix of Italianate and Mexican styles. He took his inspiration for this style from his time illustrating propaganda materials for the revolution under Dr. Atl’s guidance.

Out of all the artists who painted for the school, Orozco was the only one who did not follow orders and painted what he wanted to paint.

The painting conveys a strong political statement: the working classes, represented at the bottom of this famous mural to indicate their place at the bottom of the social hierarchy, are engaged in conflict amongst themselves, while the caricatured affluent enjoy their lavish meal. The working-class citizens are attacking one another in a self-destructive manner instead of employing their tools to construct a better community. This is regarded as an important early example of murals being utilized for speaking directly to the usually illiterate working class in an effort to better their living conditions.

The Liberated Earth With the Natural Forces Controlled by Man (1926) by Diego Rivera

| Artist Name | Diego Rivera (1886 – 1957) |

| Date Completed | 1926 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unstated |

| Location | Chapel, Autonomous University of Chapingo, Mexico |

This beautiful artwork was created for a chapel’s altar wall at a Mexican university. It is seen as the pinnacle of Rivera’s Mexican style; it is far less Italianate than his early attempts, rather adopting a distinctly Mexican style in strong earthy colors reminiscent of traditional Mexican art.

Surprisingly, given its sacred setting, the painting portrays a sensuous pregnant, naked lady, symbolizing a fruitful earth emancipated through a revolution in society.

Rivera delves more into the link between the effects of revolutions and human growth in this study. He felt that revolutionary social goals and the embrace of contemporary industrial and technological advances would change the people of Mexico into the magnificent muscular creatures depicted in the famous mural. Figures depicting the forces of nature such as wind, water, and fire surround the earth-woman. Each elemental force has been portrayed as being managed by people, who use technology to capture wind power, run industries, and utilize hydroelectricity to both control and cultivate the earth figure.

Prometheus (1930) by José Clemente Orozco

| Artist Name | José Clemente Orozco (1883 – 1949) |

| Date Completed | 1930 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | 610 x 870 |

| Location | Frary Dining Hall, Pomona College, Claremont, California, United States |

José Clemente Orozco was a little-known painter in America when he was commissioned to produce a mural painting for Pomona College. This mural is the first example of a Mexican mural artwork in the United States, expanding the movement’s importance beyond the boundaries of the country that developed it.

In terms of objectives and design, most murals in the United States up until this time were mostly decorative.

In contrast, Orozco’s ideas for Pomona were bold and very expressive. In Greek mythology, Prometheus took fire from the Olympians to give to humanity, with fire representing enlightenment and wisdom. The artist’s depiction of transmitting knowledge to the people was an apt message for the educational institution. The artwork mixes styles that were created by Orozco in Mexico with the great muscular strength of a nude by Michelangelo, an artist who had a major influence on him.

Detroit Industry Murals (1933) by Diego Rivera

| Artist Name | Diego Rivera (1886 – 1957) |

| Date Completed | 1933 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unstated |

| Location | The Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, United States |

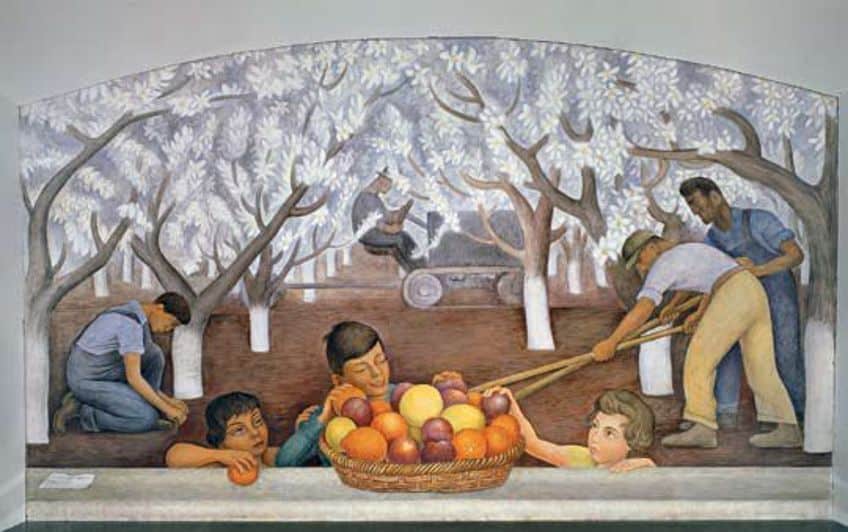

Rivera was commissioned to create a number of large-scale mural paintings for the Ford Automobile manufacturing factory, working on the paintings for around a year. These paintings are an important illustration of the shifting ideas of the Mexican Mural movement, which began as a highly politicized movement driven by socialism but had evolved into a celebration of American capitalist culture.

The artist continued to get orders when the Mexican government disbanded the Communist Party in 1929, and he was removed from the Communist Party for not protesting.

He believed these mural paintings to be some of his greatest work, and his observations of industry in Detroit inspired him a great deal. He was fascinated by the technology and human labor of industrial structures, and he developed designs that depict machines and people working in harmony, loaded with detail.

Detroit Industry Murals (1933) by Diego Rivera; Diego Rivera, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detroit Industry Murals (1933) by Diego Rivera; Diego Rivera, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of the Bourgeoisie (1939) by David Alfaro Siqueiros

| Artist Name | David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896 – 1974) |

| Date Completed | 1939 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unstated |

| Location | Sindicato Mexicano de Electricistas headquarters, Mexico City, Mexico |

Although Siqueiros was considered to be one of the “big three” Mexican muralists, he did not become popular in Mexico or globally until much later. This painting was one of the main paintings that brought him to stardom and established a subsequent style of Mexican Muralism.

It was created for the Electrical Workers Union’s headquarters, which sought a painting that would reinforce its position as an organization of public significance and strength.

As a socialist with a political agenda, the artist advocated for a democratic artistic system in which his assistant artists would be compensated equally and play major roles in the artistic decision-making process. The central wall of the painting was heavily influenced by the artist’s experiences with the Spanish Civil War. A machine in the center controls the combat, spitting coins dripping with blood. This might be interpreted as a symbol of the destructive tendencies of Capitalism and Fascism.

Relation of Man and Nature in Old Hawaii (1949) by Jean Charlot

| Artist Name | Jean Charlot (1898 – 1979) |

| Date Completed | 1949 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unstated |

| Location | University of Hawai’i-Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii |

In the early 1920s, Jean Charlot was one of the first mural painters to be appointed for the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. He was still creating murals a quarter-century later, despite being on the margins of the Mexican Mural movement. He was a French-American by birth, and his investigations into cultural self-identity from the perspective of an outsider reached beyond the people of Mexico and their leaders. He was commissioned to create a mural painting for the University of Hawai’i-Manoa in the late 1940s.

He was just as scholarly about the native people of Hawaii’s identity as he had been about the inhabitants of Mexico. In Mexico, he helped with archaeological digs to find out more about the local art and culture.

In Hawaii, he immersed himself in the culture of the island chain, learning about its customs, history, and religion. He even learned Hawaiian and developed plays in the native language. The artwork examines how Hawaiian traditions and identities are centered on their interaction with nature, from the flowers that hang around their necks to the trees that look like bodies dancing. It’s a noteworthy instance of the Mexican Muralist heritage being used outside of the country to highlight another more obscure culture’s complex customs and distinct characteristics to the general public.

That wraps up our investigation of Mexican Muralism, often regarded as one of the most important art movements to arise from this once war-torn country. Mexican murals were at first employed to communicate visual messages to an illiterate populace, which offered new possibilities for inclusiveness and communal cohesion within its people. These statements typically placed emphasis on Mexican historical traditions, cultural pride, or political propaganda. Murals were therefore seen as a far more effective means of communication than the existing formats of newspapers and pamphlets. While the early Mexican painters favored socialism, they would develop through time to depict the Industrial Revolution and capitalism. Today, Mexican Muralism is considered to be the movement that brought back the ancient traditions of frescoes.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Did the Mexican Mural Movement Begin?

The Mexican Mural movement started in 1920 at the close of the Mexican Revolution, when the new government promoted a revival of culture by ordering several public mural paintings with the goal of uniting the nation recovering from war. The works produced during this period contributed to the formation of a unified Mexican identity while also establishing a different path to European modernism. Artists and journalists from America went to Mexico to look at the finished pieces. As Obregón’s administration ended in 1924, commissions for Mexican murals stopped, and the mural painters fled to America in search of work. They hosted exhibits and painted large-scale murals, and their impact spread from coast to coast

Who Were the Big Three in Mexican Muralism?

The Mexican Mural movement was most known due to the efforts of three Mexican painters, namely José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Diego Rivera. The most well-known of the three, Rivera, is most known for his large-scale murals depicting Mexican culture, history, and society. David Alfaro Siqueiros was another well-known Mexican muralist, as well as a Communist Party member. Jose Clemente Orozco was the third of Mexico’s famous trio of muralists, and his work was noted for its critical depictions of Mexican culture. These three mural painters, along with several other important figures in the Mexican Mural movement, had a significant effect on the evolution of contemporary Mexican art, and played a significant role in making use of art as a form of political and social commentary during a turbulent era in Mexican history.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Mexican Muralism – Discover the Social Importance of Murals.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 6, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/mexican-muralism/

Anthony, J. (2023, 6 November). Mexican Muralism – Discover the Social Importance of Murals. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/mexican-muralism/

Anthony, Jordan. “Mexican Muralism – Discover the Social Importance of Murals.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 6, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/mexican-muralism/.