Nefertiti Bust by Thutmose – Learn About the Iconic Queen’s Bust

The legendary bust of Nefertiti is among the most famous treasures from the ancient Egyptian world that continues to intrigue many across the globe. The archaeological gem reveals the physical identity of the renowned queen Nefertiti, who was the wife of King Akhenaten, pharaoh of Egypt between 1353 and 1336 BCE. But who was the sculptor of this incredible artifact, and what is the history of the bust of Nefertiti? Keep reading for all you need to know about this iconic sculpture!

Gems of Egypt: The Bust of Nefertiti

One of Egypt’s most renowned sculptors, Thutmose, was an influential master artist during 1350 BCE, who was credited with creating one of the modern world’s most famous Egyptian sculptures, the bust of Nefertiti. Below, we will introduce you to the Nefertiti bust as well as its maker, Thutmose, whose work is currently housed at the Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany.

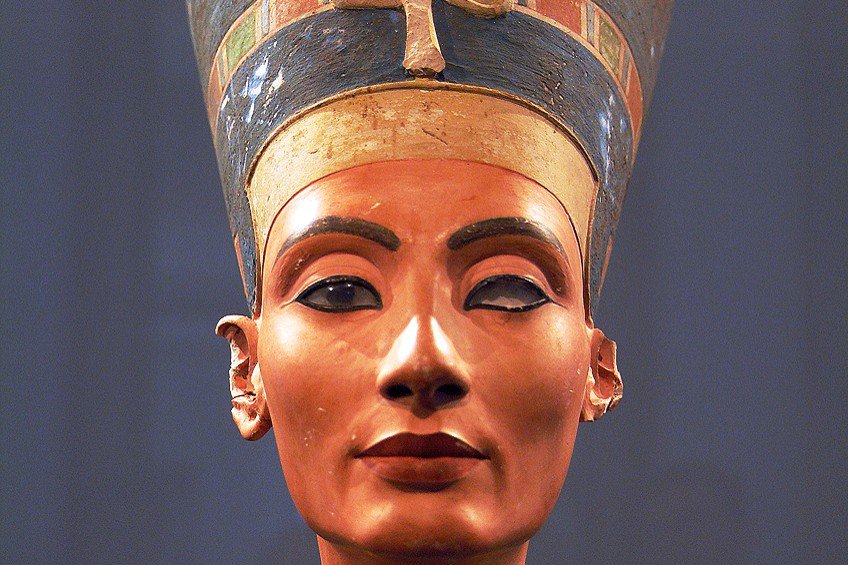

Nefertiti Bust (c. 1351 – 1334 BCE) by Thutmose

| Artist Name | Thutmose (active c. 1350 BCE) |

| Date | c. 1351 – 1334 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone, stucco, wax, and quartz |

| Dimensions (cm) | 48 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany |

Today, the world-famous Egyptian bust is recognized as a symbol of ancient Egypt itself and a reminder of the colonial period entrenched in African history. Who was Nefertiti, and who was the sculptor who made the famous Egyptian bust? Below, we will dive into the details behind the making and discovery of this ancient artifact.

Behind the Bust: The King’s Favorite Sculptor

Who was the master artist behind the Nefertiti bust, and what is the sculpture made from? The Nefertiti bust was sculpted by King Akhenaten’s favorite artist, Thutmose, who was an official court sculptor throughout the mid-14th century BCE. King Akhenaten was the 10th ruler of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty and was also recognized as Amenhotep IV in his fifth year of rulership. Thutmose owned and operated a workshop located in modern-day Amarna, which was discovered by German archeologists in the city of Akhetaten in 1912. Archaeologists also discovered an ivory horse blinker with Thutmose’s name inscribed on it, along with his job title as a sculptor.

Thutmose’s workshop contained many sculptures, including the Nefertiti bust and 22 plaster casts of faces. Eight of the faces were found to resemble individuals from the royal household, including the king’s second wife, Kiya, his successor, Ay, and his father, Amenhotep III.

As a highly respected sculptor, Thutmose’s workmanship included realistic representations of noblewomen, which was rare in the broader spectrum of ancient Egyptian conventions in art. Egyptian artists usually depicted women according to the existing ideal standards of beauty, with slender figures, beautiful youthful faces, and stylized eyes. Another small sculpture of an older Nefertiti figure was discovered at the site and featured a rounded stomach, thick thighs, and a curved line beneath her abdomen to indicate her fertility and history of pregnancy.

Alain Zivie, a French Egyptologist, discovered a decorated tomb in Saqqara, which also named a figure called Thutmose from Saqqara, however, holds different titles to Thutmose from Amarna. It was concluded that Thutmose must have held two different jobs at different points in his life.

Today, a few of his works can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.

Ancient Egypt’s Beauty: Queen Nefertiti

Who was Queen Nefertiti? Nefertiti’s title was of great power since she was the great royal wife of Akhenaten, who was most famous for the radical religious changes in Egyptian culture during the 14th century. Nefertiti, alongside her husband, implemented a form of monotheism through the Aten religion. The Aten religion was founded on the sun disc, called Aten, and was the dominant religious system that was connected to the royal family. It is also important to note that this period in Egyptian history marked the most wealth that the country had ever seen in the ancient world.

After her husband’s death around 1336 BCE, Nefertiti led Egypt as a Neferneferuaten (female pharaoh), during which her reign was marked in the history books as the fall of Amarna and its relocation to Thebes.

Her position as a female pharaoh remains a subject of debate since the female leader was also speculated to be Nefertiti’s daughter, Meritaten. Nefertiti and Akhenaten had six daughters together, one of whom was married to King Tutankhamun. Nefertiti’s name translates to “the beautiful one has arrived” with many other titles and nicknames granted to her, including “the lady of all women” and “the lady of grace”. While not much is known about her personal life before her marriage to Akhenaten, Nefertiti was first cited in reliefs found at Thebes as well as many scenes in Talatat tablets, often appearing twice as many times as Akhenaten.

Nefertiti’s name change to Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti also signified the increased strength of their cult of Aten. In multiple archaeological sites, Nefertiti was depicted as a powerful ruler worshiping the sun disc and riding a chariot in the same way that one would depict a male pharaoh. It has also been theorized that Nefertiti disguised herself as a man and took on an alter-ego called Smenkhkare, who was identified as an unknown ruler who led Egypt during the same period as Nefertiti.

Recent theories around the identification of her mummy have been speculated to be one of the two mummies discovered at the KV21B site, which was found alongside another mummy speculated to be Ankhesenamun, Nefertiti’s daughter.

Discovery of the Bust

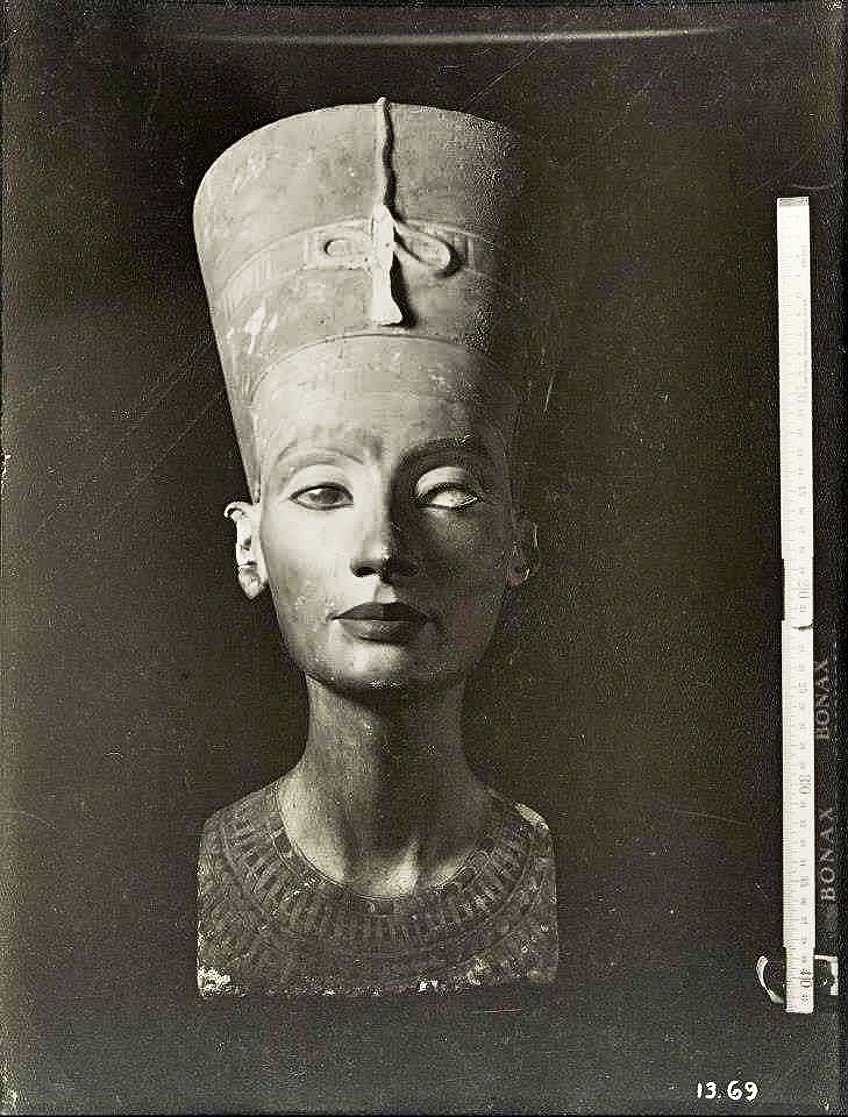

The famous Nefertiti bust was discovered in 1912 at the Amarna site by a German archaeological team, who were supported by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. The company was founded by James Simon, who led the exportation of over 20,000 Egyptian and Iraqi artifacts, as well as the exploitation of many cotton farmers to grow his wealth. Ludwig Borchardt led the excavations of the workshop of Thutmose, where he also uncovered the bust of Akhenaten and many other unfinished projects.

The same company also recorded a meeting that occurred in 1913, which described a discussion between an Egyptian official and Ludwig Borchardt on the division of artifacts as an agreement between Egypt and Germany.

The discovery of the Nefertiti bust was concealed and the sculpture was smuggled out of Egypt by Ludwig Borchardt as a personal win for Germany. The Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft maintained that the negligence of the sculpture and its concealment was untrue since they claimed it had been on the top of the exchange list during the deal between Egypt and Germany. The negligence of the bust became a topic of sensation after Borchardt showed the Egyptian antique inspector a misleading image of the bust and claimed it was crafted from gypsum and not limestone.

An Analysis of the Bust of Nefertiti

The Egyptian bust of Nefertiti itself has many fine details and iconic features that make it a unique piece in the history of Egyptian archaeology. The bust itself was created from limestone, which Thutmose then coated in stucco with varied thicknesses. He used a layer-by-layer approach to apply the stucco, which was revealed in a 2006 CT scan from the Imaging Science Institute Charité, Siemens.

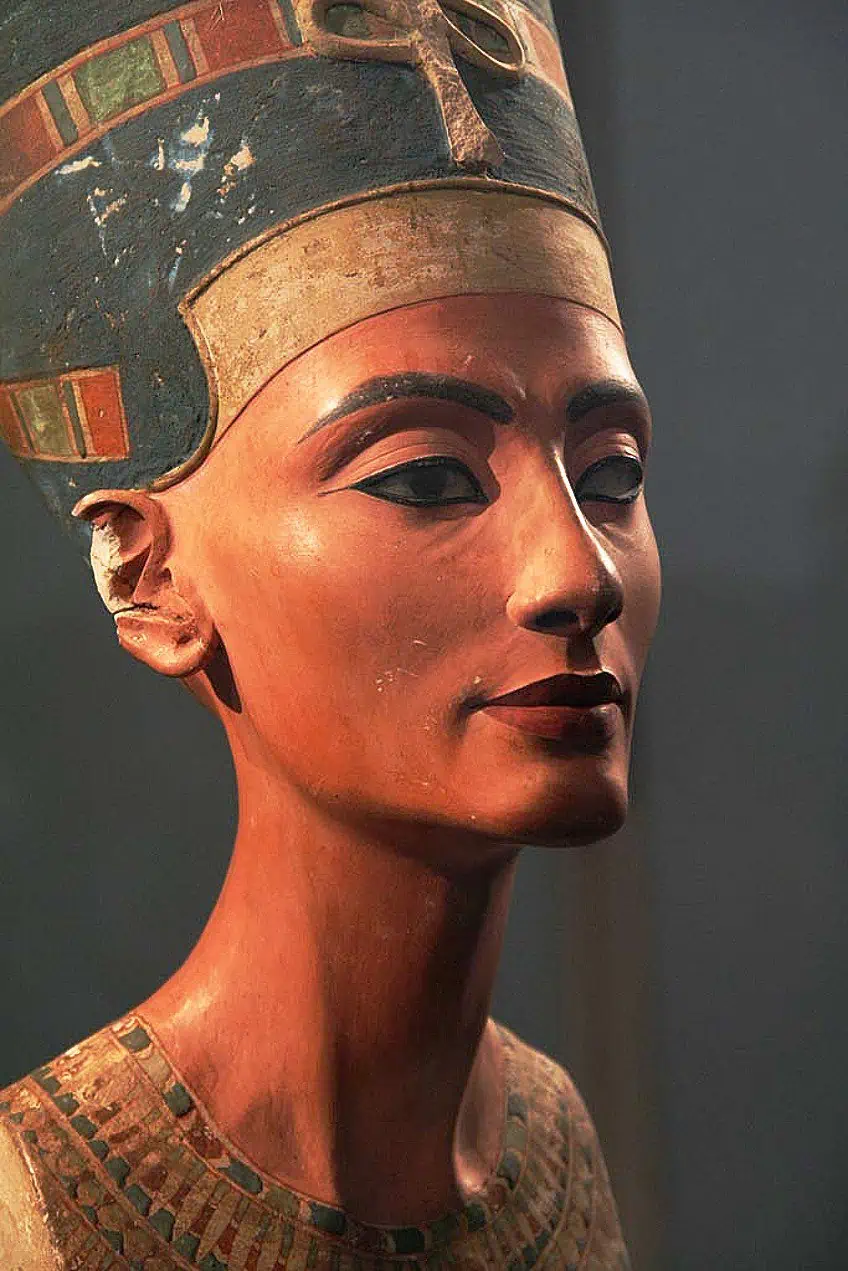

The bust weighs approximately 20 kilograms and features a crown cap, a broken uraeus (cobra), and a golden diadem band. Her collar showcases a floral pattern and her ears are damaged. The bust was sculpted in a Classical Egyptian style, which was reminiscent of Amarna art styles from the period. It has been speculated that the incomplete bust was a model from which Thutmose used to create other royal portraits.

The first description of this three-dimensional portrait was described in 1912 by Ludwig Borchardt, who was the leader of the archaeological excavation at Tell el-Amarna. He described the bust as 47 centimeters high, with a flat-cut blue wig and a ribbon wrapped around it. He also described the color of the bust as though it had just been painted. The most famous quote from his diary entry was “Description is useless, must be seen”, which is all one truly needs to know to grasp the beauty of the sculpture.

In 1923, Borchardt drafted a proper description, which emphasized the impressive nature of the bust’s preservation, the missing left inlay on the eye, chips across the face, and the delicate rendering of the muscles around her neck.

Pigments on the Nefertiti Bust

One of the most captivating details about the bust is its vibrancy, which has been preserved in such remarkable conditions for centuries. The bust’s lifelike look and feel is a masterpiece. It was complimented by the use of Egyptian pigments such as red ochre, carbon black, yellow pigment, and green frit. What gives the bust its signature Egyptian element is its use of Egyptian blue, which was painted in various shades and even mixed to create Nefertiti’s skin tone. Portrait of Queen Nofretete (1923) contained a chemical analysis of the pigments found in the bust and the results listed the following pigments: chalk (white), coal and wax as a binder (black), orpiment (yellow), finely crushed lime spar and red chalk for the skin color, and a mixture of copper and iron oxide with crushed frit for green.

The bust has multiple layers of paint, applied with incredible accuracy. In 2009, a test by Rathgen-Forschungslabor from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin confirmed the authorship of the work and revealed the pristinely preserved layers of paint.

Thutmose also made sure to paint Nefertiti’s eyebrows one single strand at a time in a cross-hatch pattern. Despite her superficial collar, Nefertiti’s facial structure is nearly symmetrical and includes beeswax with black pigment for her right iris and a polished rock for her cornea. The bust’s missing left eye is also a topic of debate, however, Borchardt concluded that it never existed in the first place after he thoroughly searched the site.

Beneath the Surface

The Nefertiti bust underwent its first CT scan in 1992, which revealed cross-sections from every five millimeters of the bust. In 2006, it was then scanned again by Dietrich Wildung, the director of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, who discovered wrinkles on the bust’s eyes and neck. The scan revealed that Thutmose did utilize gypsum to add signs of aging on Nefertiti’s cheeks and under eye areas to achieve realistic perfection. The scan was managed by Alexander Huppertz, who was the Imaging Science Institute’s director who uncovered the inner core of the sculpture.

The results showed that her inner face was modeled with creases and swelling around her nose, which was evened out by Thutmose with stucco layers.

Whether the inner model was a first draft or simply a design method, it was theorized that the smoothening out of the wrinkles indicated the ideals of the era’s aesthetics. The Nefertiti bust had thus become an iconic part of Egyptian history and Berlin’s culture, such that it was also featured in postage stamps across Germany in 1989.

Protecting the Nefertiti Bust

Since the discovery of the Nefertiti bust, the sculpture had traveled across Berlin and was even stored briefly at a salt mine in Thuringia. In 1913, the bust was exhibited at the home of James Simon and was thereafter moved to the Berlin Museum under much secrecy. By 1918, the bust remained closed off to the public, and in 1920, it was donated to the museum. It was only in 1923 that the Nefertiti bust was revealed and later exhibited at the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.

The sculpture was then exhibited at the Neues Museum, however, with World War II in the picture, the museum closed and many artifacts were sent off to safe storage sites.

The Queen Nefertiti statue was stored in the cellar of the Prussian Government Bank and moved to a flak bunker tower in 1941. After the Neues Museum was bombed in 1943, the bust was transported to a salt mine in Merkers-Kieselbach, Thuringia in 1945. It was not long thereafter when the Queen Nefertiti statue was retrieved by the American Army, who moved it to their fine arts branch.

The bust also traveled to Frankfurt and was shipped to the U.S. Central Collecting Point, Wiesbaden, where it was exhibited in 1946. The Nefertiti bust was on display for 10 years at the Museum Wiesbaden and by 1956, it was transferred to the Dahlem Museum. Around 1967, the Nefertiti sculpture was relocated to the Egyptian Museum, where it remained until 2005.

Thereafter, the bust found itself at the Altes Museum and eventually returned to the Neues Museum in 2009, where it remains today.

The Face of Imperial German National Identity

Of significant note is the fact that the image of Nefertiti and the existence of the bust as a precious German-retrieved artifact was tied to imperial national identity. The bust became the new monarch of Germany by the 1930s as it was described in the press as a treasure of Prussia Germany.

Political leaders like Adolf Hitler were also aware of the bust’s existence and acknowledged it as “a true treasure” that he wished to build a museum for it.

After the Second World War, the Nefertiti bust had become a symbol of national identity for German states, including West and East Germany, and by 1999, it also appeared on a political poster for Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, as a symbol to promote the party’s promise of a multicultural society. Another theory proposed by Claudia Breger suggests that Nefertiti’s bust was established as a symbol of German identity to challenge British-led Egypt and the discovery of Tutankhamun.

Authenticity and Repatriation

Since the discovery of the bust, there have been two major publications that propose that the sculpture was perhaps a modern fake to please Prince Johann Georg of Saxony, to whom the actual sculpture was presented by Borchardt. Allegations suggesting that Borchardt also experimented with ancient pigments on a modern model that he made were done to avoid offending the prince. This was proposed by Henri Stierlin, a Swiss art historian who described his claims in his book, Le Buste de Nefertiti – une Imposture de l’Egyptologie.

He further argued that the bust’s missing left eye would have been seen as a sign of disrespect in Thutmose’s era, which is further supported by the fact that no scientific data was published on the sculpture upon its discovery.

The various publicity allegations have since been dismissed since data from radiological tests have proven the bust’s authenticity. Egyptian authorities have also negated Stierlin’s claims entirely, stating that he is delusional. Furthermore, the Nefertiti bust has long remained a hot topic in debate circles for its repatriation back to Egypt since it is part of Egypt’s history. Germany had initially opposed its repatriation with figures like Hitler refusing its return. Egypt had also requested that the United States return the artifact, but they had insisted that the officials correspond with German authorities. Negotiation attempts were made in the 1950s with not much of a response but in 1989, the bust was visited by Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who stated that the sculpture was the best representative of Egypt in Berlin.

Another advocate for the return of the Nefertiti bust was Zahi Hawass, who was the former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs that claimed that the bust was removed from Egypt illegally and the acquisition of the sculpture was led misleadingly. Hawass also appealed to UNESCO to join the debate for the repatriation of the artifact. By 2007, Hawass also attempted to lead a global boycott of German museums as an act of “scientific war”, while also threatening to ban the display of Egyptian artifacts in the country.

An organization called CulturCooperation based in Hamburg also advocated for the return of the sculpture through a campaign dubbed “Nefertiti Travels”, which involved the distribution of postcards with the phrase “return to sender”. When the bust was eventually relocated to the Neues Museum in 2009, its correct location was also questioned.

Among the arguments for the bust to remain in Germany included reasons such as the sculpture being too fragile to transport, a hesitation to lend the bust to Egypt for fear of permanent loss, as well as insufficient legal arguments for its return. In 2009, documents related to the discovery of the sculpture described the artifact as a painted plaster bust of an Egyptian princess, however, Borchardt’s journal clearly described it as the head of Nefertiti. The Neues Museum attracted hundreds and thousands of visitors each year since the sculpture was displayed. Today, many replicas are produced at Gipsformerei, which is a part of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin to cater to collectors and museums across the globe.

The mesmerizing history of the incredible Nefertiti bust as a memory of the famous Egyptian queen and historical artwork continues to intrigue many about the ancient history of Egypt. The bust of Nefertiti remains a relevant subject of debate to consider when it comes to the notion of repatriation and the conditions that dictate when an artifact should be “returned to sender”.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Nefertiti Bust?

The Nefertiti sculpture is a famous Egyptian bust that depicts the 14th-century BCE queen Nefertiti, who ruled alongside her husband, Akhenaten. The three-dimensional portrait is considered to be an important part of Egyptian history since it provided researchers with visual information about the appearance of Nefertiti and the artistic styles of Amarna, where the sculpture was discovered. The bust is currently on display at the Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany.

Who Was Nefertiti?

Nefertiti was the queen of Egypt during the 14th century BCE and the chief consort of the Egyptian pharaoh, Akhenaten. Nefertiti was recognized as one of the most beautiful women in Egypt, who led the cult of the sun God or sun disc, Aten. Nefertiti also reigned over Egypt for a brief period of time after the death of Akhenaten.

Who Sculpted the Nefertiti Bust?

The famous Nefertiti bust was sculpted by a sculptor known as Thutmose, who was also considered to be the king’s best sculptor and was employed by the royal court. Thutmose ran a workshop in Amarna, where the bust was found in 1912.

Why Is the Nefertiti Bust a Controversial Sculpture?

The iconic Egyptian bust of Nefertiti is considered to be a controversial sculpture since it has become a symbol of German national identity following its discovery and relocation to Germany. The highly coveted artifact is also the subject of repatriation debates since its initial discovery and transportation out of Egypt has been questioned and criticized as misleading. The allegations for its removal from Egypt were found to be misleading since the artifact was listed as a sculpture of a princess, while the archaeologist who discovered the bust described it in detail in his journal, as the Nefertiti sculpture.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Nefertiti Bust by Thutmose – Learn About the Iconic Queen’s Bust.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 5, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/nefertiti-bust-by-thutmose/

Davis, L. (2023, 5 September). Nefertiti Bust by Thutmose – Learn About the Iconic Queen’s Bust. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/nefertiti-bust-by-thutmose/

Davis, Liam. “Nefertiti Bust by Thutmose – Learn About the Iconic Queen’s Bust.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 5, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/nefertiti-bust-by-thutmose/.