Orientalism Art – A Detailed Look at Orientalism Art History

What is Orientalism art? The Orientalism definition is the depiction in Western art of the East, which regularly blurs the distinction between reality and imagination. Orientalist artwork flourished in the 19th century, and it is probably most remembered today for producing beautiful Oriental paintings. Read further if you would like to explore the exotic feeling world of Oriental artists and Orientalism art history.

What Is Orientalism Art?

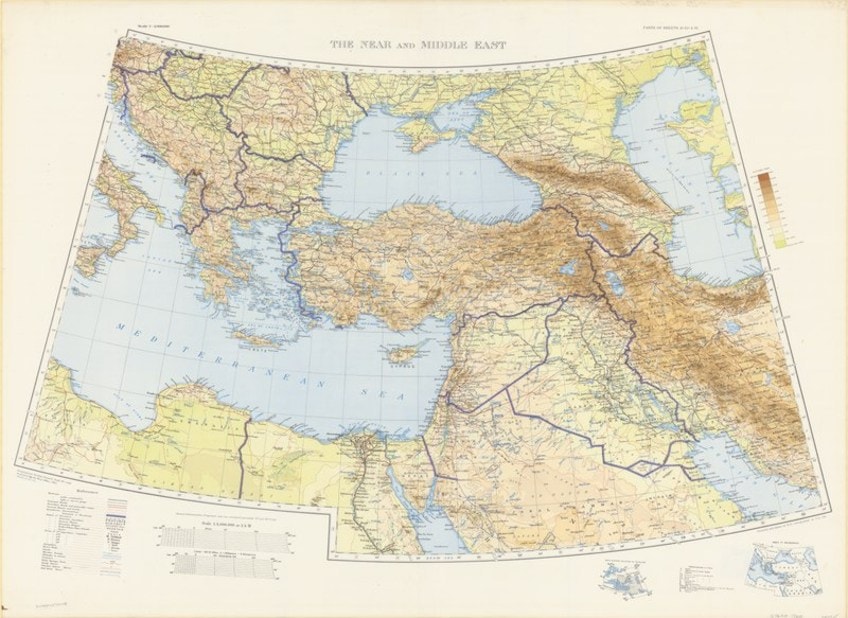

Oriental paintings became prominent in the 19th century as North Americans and Europeans grew more interested in traditions other than their own. The majority of the Orientalist artworks were created by Western artists to meet the growing public curiosity about the far-off lands of North Africa and the Middle East.

Numerous Oriental artists visited the locations they portrayed, whether it was Jerusalem, Constantinople, Cairo, or Marrakesh.

Others ventured no farther than Vienna or Paris for ideas, relying on a combination of photographic images, artifacts, and their own creativity. Recurrent imagery ranged from realistic drawings of ordinary life to exotic harem scenes. Appreciation for Orientalism art grew along with European colonial activities.

This gave troops, merchants, and Oriental artists opportunities for increased contact with these nations’ locales and cultures.

Orientalism Art History

While certain Oriental artists aimed for realism, most others condensed these nations’ distinct cultures and traditions into a generic version of the Orient. The Western perception of the Orient was essentially a fabrication of the Europeans – a land of enchantment, unusual animals, and exotic landscapes.

Orientalist artwork, which was generally categorized as Academic Art, embraced a wide range of genres and subjects, from vast historic and mythological works to nude figures and depictions of the interiors of various domestic and public spaces.

The Emergence of Orientalism Art

The Venetians were engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire from 1463 until 1479. Venice was conquered in several territories and was compelled to pay compensation in order to resume trade on the Black Sea. Gentile Bellini, the official state artist for the Doge of Venice, was dispatched as part of a cultural envoy to serve the Sultan in 1479 by the Venetian authorities. In 1481, when Bellini returned to Venice, he began to integrate Oriental influences into his artwork.

Other painters, such as Veronese, started to include similar themes in the emulation of Bellini, and as a consequence, a multitude of Venetian artworks depicting Middle Eastern topics have survived.

In some Orientalism art, Christians are dressed in Western garb, while Jews are dressed in Oriental attire. This divide, which identified Jewish people using Oriental imagery, became a standard art treatment at that time. In 1536, France joined the Franco-Ottoman Alliance, which lasted until 1798 and resulted in a number of cultural and academic exchanges.

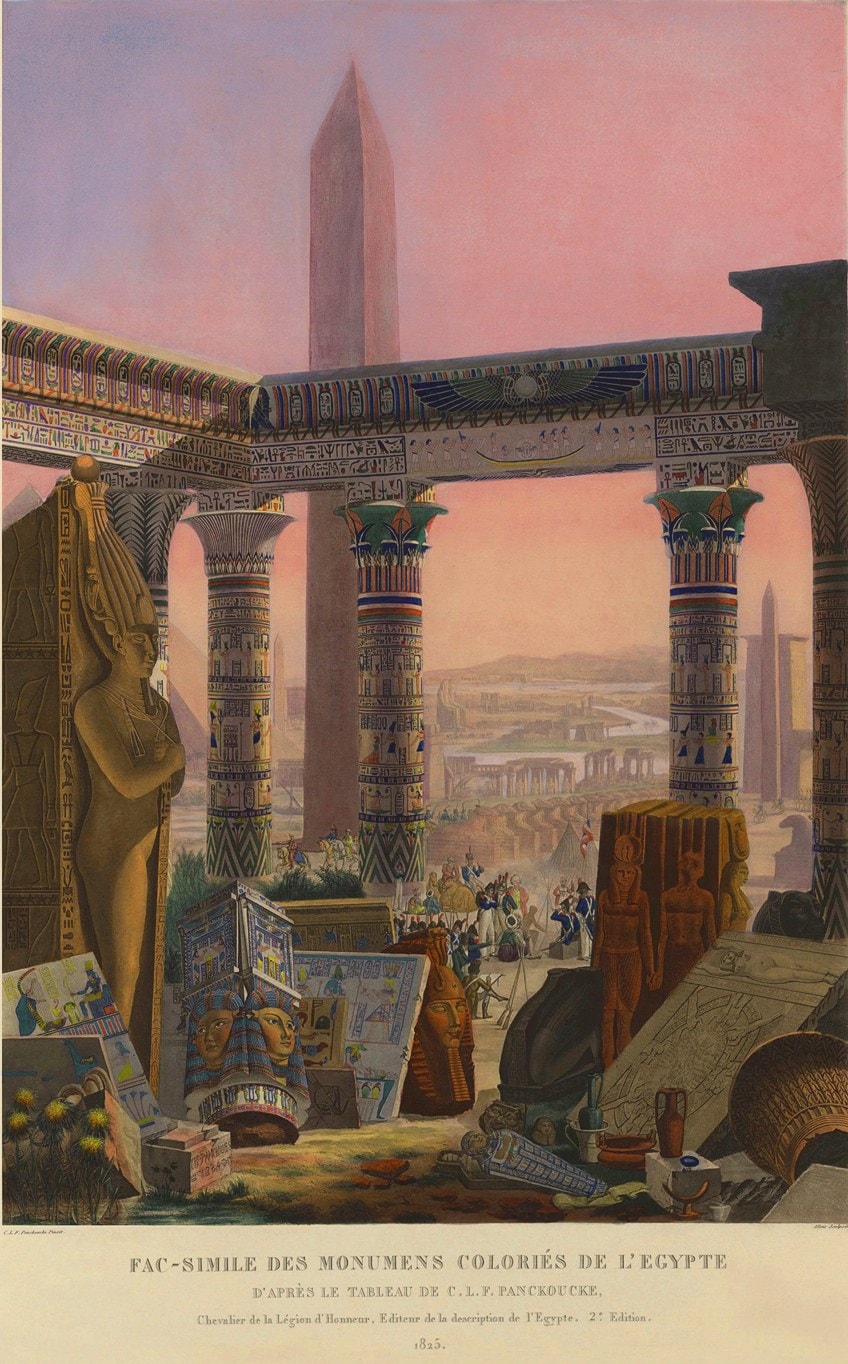

Throughout the 1700s, Turkish products became quite popular in France, and this was represented in Period art. Turquerie, a style pioneered by painters Charles-André van Loo, Jean Baptiste Vanmour, and Jean-Étienne Liotard, became an aspect of Rococo painting. As a fully formed concept, Orientalism art started with Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 and control of the nation until 1801, resulting in an inflow of Egyptian commodities into France.

Egyptian themes that derived from tombs, funeral columns, and temples inspired French architecture and decorative art.

Later Developments

In 1893, the Society of French Oriental Artists was established with the goals of spreading Orientalist artwork and inspiring French artists to go to Eastern nations. The Society’s prominent members were mostly recruited from the Algerian group of artists, including Maurice Bompard, Alphonse-Etienne Dinet, and Paul Leroy. From the Society’s inception until his death in 1925, art scholar Leonce Benedite served as president.

Through its monthly Salons and periodicals, the Society offered a collective purpose for Oriental artists, yet it was also perceived as supporting colonial control in the Middle East and North Africa.

Notwithstanding the efforts of such organizations, interest in Orientalism art was already starting to wane by the last years of the 19th century. The institutional art approach connected with it appeared conservative and out of date when new movements such as Tonalism, Impressionism, and post-Impressionism emerged in the late-19th century.

Nevertheless, Japonism, which was strongly tied to Orientalism, impacted many of these groups. Influenced by Orientalism, Primitivism was motivated by African art, as painters like Paul Gauguin gravitated toward Tahitian topics and themes, and subsequent artists like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were also inspired by African art.

Artists such as Pablo Picasso, Auguste Macke, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Oskar Kokoschka created Orientalist-inspired imagery far into the 20th century.

Orientalism Art Styles and Concepts

Orientalism art had a significant impact on religious paintings, as painters strove to bring Biblical images to life. This is evident in Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps’ Joseph Sold by His Brethren (1838), which is set amid authentic local environments. In the 1850s, English painters like William Holman Hunt journeyed to Palestine to include ethnographically realistic elements in his paintings, and the Russian Peredvizhniki school employed a Realist style in their religious artworks that were set in the Holy Land.

Orientalist Genre Paintings

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps was the most well-known Orientalist genre artist. At the 1831 Paris Salon, he presented seven Oriental paintings portraying everyday activities and scenes in the Middle East, including The Turkish Patrol (1831), which helped establish his career. His Orientalist artworks, which depicted Middle Eastern youth at play or shopkeepers at work, were especially beloved among the working class and inspired painters such as Eugene Delacroix.

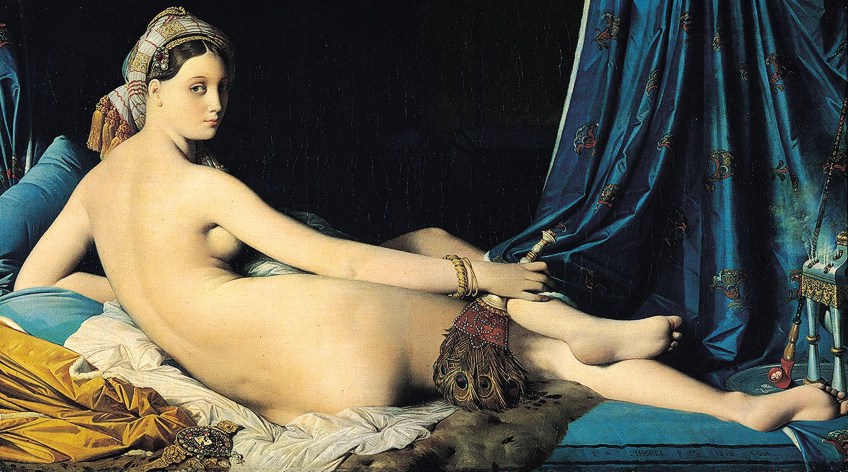

The harem theme was the most prominent, while images of the slave market were strongly associated with it.

All of these pieces featured the female slave naked, emphasizing the paleness of her skin. The success of the genre was based on the image of the East as a destination where one may seek sexual experiences unavailable in the West. The White Slave (1888) by Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouy is a classic illustration of this style. Because males were not permitted in harems, painters such as Ingres relied on their own imaginations and rumors, as well as European women, to produce these Oriental paintings.

Contemporary art scholars interpret the masculine gaze entering the prohibited world of the harem as expressing the Western urge to dominate the country and the domain of “the others”.

Orientalist Design and Architecture

Orientalism affected design and architecture at first by incorporating Egyptian patterns and motifs into the British Regency and French Empire styles and Egyptian-themed furnishings and decorations were popular among the wealthy elite.

The Egyptian-inspired aesthetic was also seen in public landmarks and architectural ornamentation.

Although the major architectural aesthetic of the era was Neoclassical, linking the emerging British and French empires with the Roman Republic, Egyptian attributes such as narrowing window frames, papyrus columns, and the incorporation of imagery such as Hathor’s head, the lotus blossom, and the sun disc were utilized. To create imaginary Oriental interiors, the Oriental or Moorish Revival style featured pointed arches, elaborately patterned trimmings, Turkish cupolas, and Islamic tiling.

The Royal Pavilion (1822) in Brighton, combines influences from the Middle East with Indian Islamic architecture.

Photographic Orientalist Artwork

Maxine du Camp was a trailblazer in Middle Eastern travel photography. He ventured to North Africa and the Middle East with his friend Gustave Flaubert in 1849, who would subsequently author the classic French book Madame Bovary (1857). Du Camp produced hundreds of calotype images of important places, some of which were published in the very first photography travel book, Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, Syrie (1852).

Auguste Salzmann was another well-known photographer who was appointed by the Ministry to research and captures the famous locations of the Holy Land.

Photographers such as Félix Bonfils and Francis Firth started creating photographic postcards and souvenirs for Europeans visiting the Middle East in the 1860s. Bonfils relocated to Beiruit and began creating photographs to represent the Orient’s “immaculate essence and unique allure.” Images were frequently posed and manufactured in the workshop, and what distinguishes most of Bonfils work is his intentional attempt to represent what they considered to be a timeless, immutable Orient.

They attempted to suit their and other Europeans’ assumptions and desires by deliberately selecting just specific aspects from the local environment. Local photographers exploited Orientalist stereotypes and responded to increased demands for Orientalist-style photos, such as Pascal Sébah, who founded his workshop in Istanbul in 1857. Such visuals also influenced the imaginations of the artists; for example, Jean-Léon Gérôme relied on diverse Middle Eastern photography to produce his composite works.

Many of the images captured during this period reflect these ideas, as they became real visual archives to illustrate an imagined world.

Oriental Paintings of War

Antoine-Jean Gros pioneered the creation of epic, militaristic Orientalist artworks, such as his Bataille d’Aboukir (1799), which depicted a historical battle waged against the Ottoman Empire by Napoleon. Orientalist artworks like these were promoted by the Napoleonic state propaganda operations, and war depictions, generally representing valiant French troops and operations against Muslim armies, became fashionable.

Although reimagined within the Romanticism Movement, these motifs persisted throughout the mid-1800s, fueled by successive conflicts with the Ottoman Empire.

Oriental artists relied on ancient history as well, as evidenced in the Defeat of the Cimbri (1833), by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, a Romantic depiction of the Roman conquest and slaughter of the Cimbri tribe in 102 AD. The majority of these works linked their Oriental themes and locations to barbaric violence and barbarism.

Important Orientalist Artworks

Orientalism art also spread and perpetuated prejudices about Eastern traditions, most notably a lack of “civil” conduct and perceived disparities in morals, sexual behaviors, and mentality of the citizens. This was frequently connected with propagandist operations launched by French and British colonial powers.

These representations are best understood within the framework of Europe’s economic and political interactions with Eastern regions at that time.

Many Orientalist artworks are imbued with rich hues, notably reds, golds, oranges, and blues, as well as ornamental embellishments, which functioned in combination with the application of light and shadow to produce a sensation of hazy heat that the Western world would associate with the perception of the Orient.

The Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834) by Eugène Delacroix

| Artist | Eugène Delacroix (1798 – 1863) |

| Date Completed | 1834 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | The Louvre Museum, Paris |

This picture portrays four ladies in an Eastern setting, complete with Persian carpets and handcrafted tapestries. The woman on the left is reclining in an odalisque stance, as her eyes admire the observer. Two ladies appear to be conversing on the right, and a slave worker turns as if captured in midstride as she departs the room.

The design and attitudes of the seated ladies are inviting and appear to welcome the visitor into the private room; nevertheless, this is contrasted with the lady on the left’s confrontational attitude.

Although the artwork lacks overt sexuality, the women’s loose attire, as well as Orientalist motifs like the addition of a narghile pipe, allude to their function as courtesans. The artwork contrasts Delacroix’s careful studies of attire and interior decorating undertaken during his tour to Tangiers in 1832 with his integration of these into the European vision of the harem’s interior and inhabitants.

Delacroix used his systematic methods of contrasting color to provide Romantic momentum to the Orientalist style of harem artwork with this piece.

The warming and lively color palette, together with the subtle depths of the shadows and the shafts of sunlight falling diagonally into the space from an inferred window on the left, produces an impression of pleasant and lively closeness.

Scene in the Jewish Quarter of Constantine (1851) by Théodore Chassériau

| Artist | Théodore Chassériau (1819 -1856) |

| Date Completed | 1851 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

This Orientalist artwork portrays two Jewish ladies and an infant sleeping in a rope-suspended cradle. The room’s basic furnishing and plain hues juxtapose with the vibrant color scheme of the women’s attire, head coverings, and accessories. The lady on the right, whose attention is fixed on the baby, exudes maternal concern, whilst the younger lady on the left appears to be daydreaming. Chassériau blended his instructor Ingres’ concentration on realistic lines with the influences of Delacroix’s rich hues to develop his own distinct aesthetic, conveying the emotional weight of his themes.

During a journey to Algeria in 1846, Chassériau encountered this scenario and drew a rough drawing, saying that he had seen some truly peculiar things: primal and overpowering, affecting and strange.

At Constantine, which is located high in the mountains, one may observe Arabs and Jews living as they did at the dawn of time. He communicates the peculiarity of the setting in this shot by highlighting the cradle basket dangling from the ceiling, its ropes forming a triangle that covers the middle of the frame, which is contrasted with the domestic and normal appearance of the ladies, a juxtaposition of the commonplace and exotic.

The women’s clothing suggests they are rich, yet this contradicts their surroundings, and the woman pictured to the left seems not to have shoes, a feature identified by Europeans with the “primitive East”.

Aside from that, the ladies themselves are multifaceted and unique, rather than clichéd. The artist appears to have been looking for a means to revitalize and update current portraiture by stressing his characters’ innermost psychological states.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860) by William Holman Hunt

| Artist | William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910) |

| Date Completed | 1860 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, UK |

In William Homan Hunt’s picture, Christ is seen as a boy, facing the audience and leaning toward Mary, who talks into his ear, while behind them, Joseph waits intently. A swarm of Jewish seniors and younger academics, to whom the child had been speaking, starts in the bottom left and stretches into the shrine’s darkened interior.

The juxtaposition between the Holy Family, who are dynamically erect and Europeanized in style, and the Orientally garbed Jewish elders, who are quietly reclining on the floor, many of whom are veiled in darkness, is striking.

A fishing vessel with numerous fishermen, a dove, and a man worshiping in front of the shrine all hint at the 12 disciples, the Holy Spirit, and the prophecy. The child leans forward, his gaze directed at the observer, conveying the sacred magnitude of the occasion. Hunt was a pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood pioneer, and this piece reflects the group’s focus on portraying lifelike settings from literature, in this instance the holy tale of how Mary and Joseph, searching for Jesus who had somehow wandered off on his own, discovered him lecturing in the temple.

The artist wanted the artwork to be ethnographically authentic, so he traveled to the Middle East to discover the people and their culture for himself, which he accurately reproduced in this painting. As a literary device, the accurate detail that many commentators saw as the embodiment of a strictly technical approach serves to enhance the audience in experiencing the moment.

The scene’s Orientalism, as well as the contrast between the Oriental representation of the Jewish audience and the Westernized aspect of the Holy family, continues to spark discussion today.

Pilgrims Going to Mecca (1861) by Léon Auguste Adolphe Belly

| Artist | Léon Auguste Adolphe Belly (1827 – 1877) |

| Date Completed | 1861 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

A caravan lead by camel riders travels the desert in such heat that color appears washed out and shadows take on a stark hardness. As though drawing the observer into the caravan, the convoy covers the canvas from the middle left of the vast horizon to the center field, where the travelers come into clear focus. The onward motion instills a sense of determination.

Each figure’s lifelike detail offers a feeling of uniqueness, while the group’s tight density communicates a sense of common purpose and solidarity.

Belly journeyed to Egypt in 1856 to make the sketches for this piece, explaining that he wished to portray, like Courbet, “the genuinely lovely and intriguing elements of our fellow men’s daily existence.” The artist uses a realistic technique in the minutiae, such as the camels’ worn knees and the irregular surface of the land. At the same time, the camels are magnified in scale, as demonstrated by the shrunken figure of the individual clothed in white strolling in the bottom center, and the convoy is led by a savage-looking person, shirtless and with a shaven head.

As a consequence, the artist highlights these unusual qualities to his viewers while still conveying that the scenario is a reality that has been accurately depicted.

Bashi-Bazouk (1869) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

| Artist | Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 – 1904) |

| Date Completed | 1869 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

This arresting image of a black gentleman in profile emphasizes his regal demeanor with a magnificent silk tunic and an ornate and wonderfully colored headgear. The color scheme and application of light and shadow focus the audience’s eye on the textures of the fabrics and the hues of the man’s skin, creating an aesthetically stunning and exotic impression.

Gérôme designed this work in 1869 following one of his frequent trips to the Middle East, but it was planned and executed in his Paris workshop, as with the majority of his Orientalist artworks.

A figure has been dressed in the attire and weapons obtained by Gérôme on his expedition to represent a Bashi-Bazouk, or ‘broken skull’ warrior, who was a member of the insurgent groups that battled for spoils with the Turkish troops in defense of the Ottoman Empire.

The artist’s arrangement of the picture demonstrates how the opulent fabrics and exotic aspects of the Eastern culture were cherished by the European viewers just as much as the individuals represented.

As a consequence, the sitter appears unharmed by war, his ‘broken skull’ signifying troops who fought without the hierarchical command of the professional forces and were especially renowned for their savagery. Instead, the image is reminiscent of a current fashion shot.

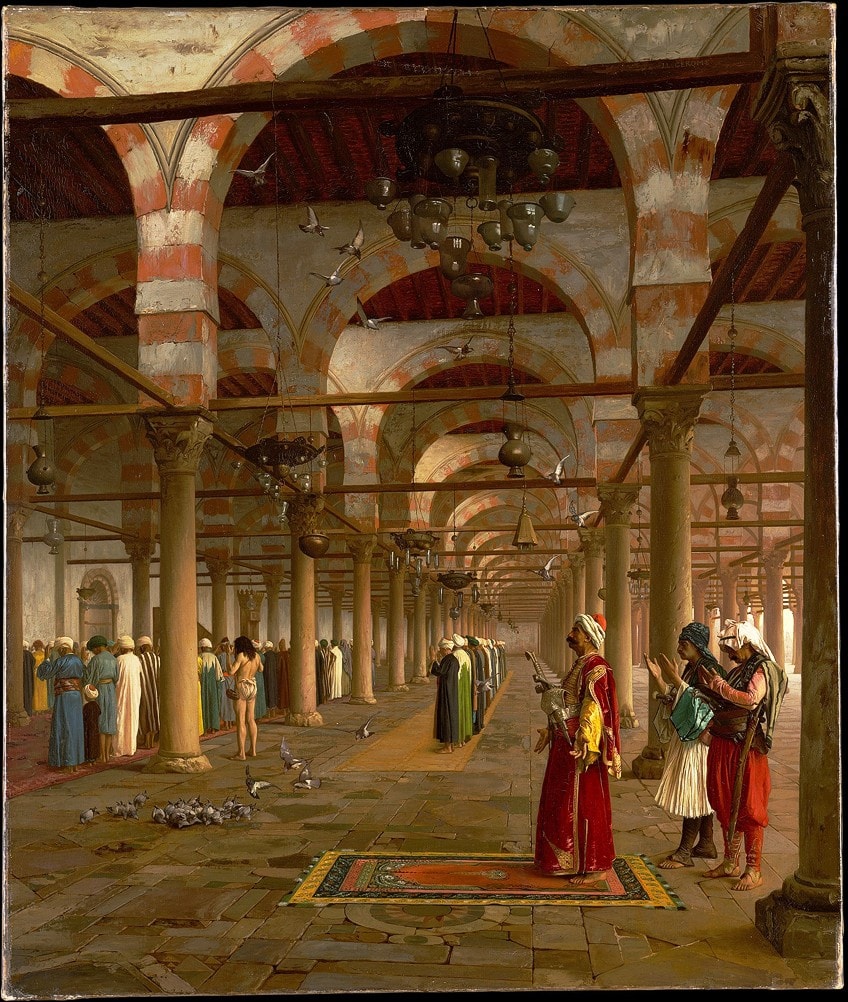

Prayer in the Mosque (1871) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

| Artist | Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 – 1904) |

| Date Completed | 1871 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

This artwork depicts the inside of a mosque in Cairo, devotees congregate for one of several daily devotional services. The worshipers comprise the lower third of the painting, while the center third is composed of crossing beams that provide dramatic aesthetic value by crossing diagonally with the vertical lines of the pillars. The repeated forms of the arches take up the upper part of the painting. The split and planned architectural components in the artwork provide a sense of equilibrium.

From an affluent individual kneeling on a meditation rug to a single holy man donning just a loincloth, the picture depicts a cross-section of civilization.

A diagonal line of praying men spreads across the middle of the painting into the background, indicating the mosque’s vastness. The accent on the structure, with its gloomy and light-filled recesses and recurring white and red patterns, creates a sense of calm devotion, of the worshipers as parts of a bigger reality. Simultaneously, the figures appear motionless, which, when paired with the building crossbeams, suggests a world stuck in time.

Gérôme started to paint a sequence of Muslim folk during worship in mosques in the 1860s, and this is regarded as one of his great works.

At the period of his 1868 voyage to Egypt, the Mosque of Amr had fallen into ruin and would not be restored until 1875, thus he relied on sketches from books, the writings of Orientalist historians such as Edward William Lane, photos, and other reports to ensure the realism of the work’s features. Gérôme, a harsh opponent of Impressionism, accentuated the viewpoint and structural composition of the Neoclassical heritage in this Orientalist artwork.

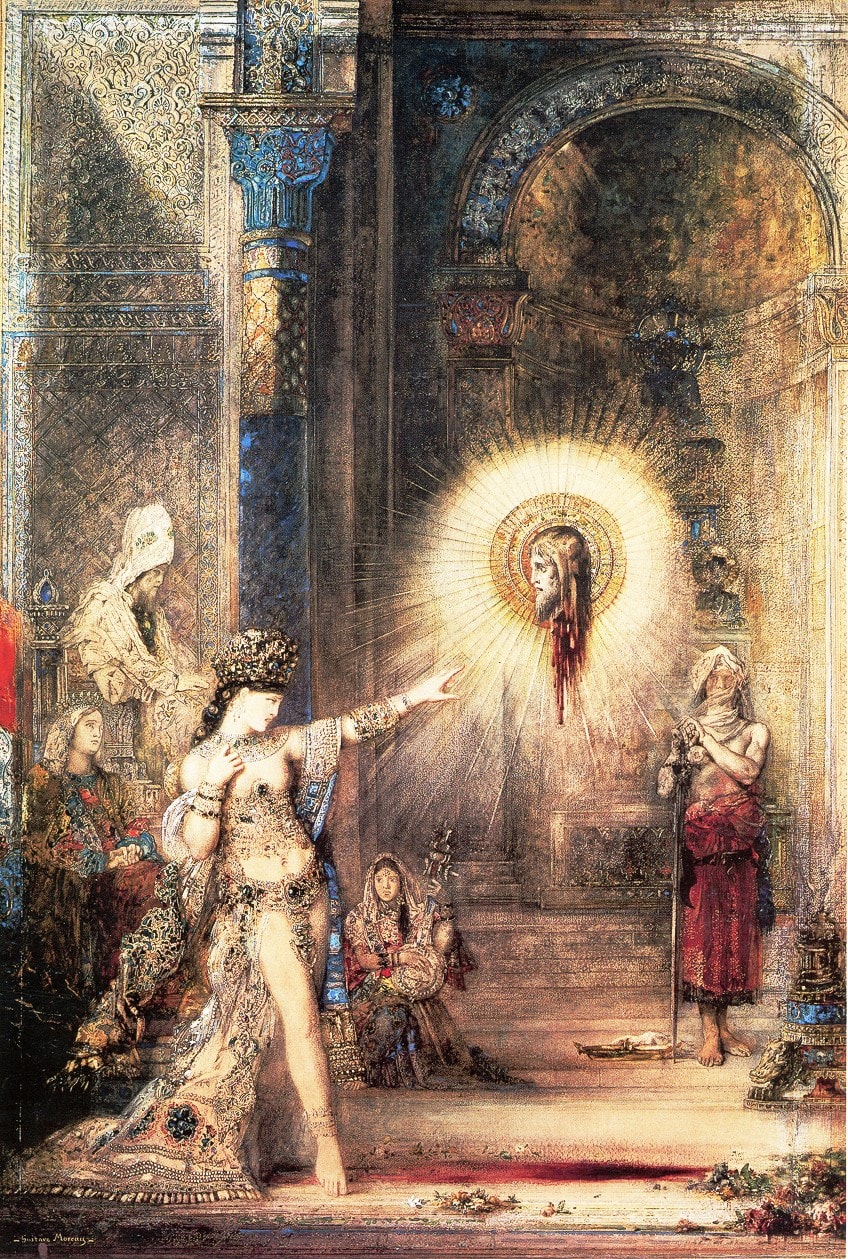

The Apparition (1876) by Gustave Moreau

| Artist | Gustave Moreau (1826 – 1898) |

| Date Completed | 1876 |

| Medium | Watercolor |

| Location | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

This Orientalist artwork portrays Salome, clothed in provocative and glittery Oriental-inspired attire, pausing in her performance to gesture toward the figure of John the Baptist, whose halo emits light and is hovering in the middle right of the image. Behind Salome, one can see her mother, clothed in lavishly colored garments, and King Herod, clad in white Oriental garments, look at the specter without emotion.

The executioner, with his blade at his side, and the younger female playing the lute both face the audience, seemingly ignorant of the decapitated head hovering between them.

Because only Salome responds to the apparition, the image becomes purposefully ambiguous, hovering between perception and illusion. The image was inspired by the Alhambra in Granada, and its faded golden glow, mixed with his original watercolor method and use of etched lines and highlights, earned him the moniker “Byzantine.”

Moreau defined Salome as “a restless and fascinating lady, wild by nature, and so dissatisfied with the total gratification of her cravings that she gives herself the sorrowful satisfaction of watching her opponent humiliated in this image. As an artist, he grew infatuated with Salome, producing over 20 canvases and watercolors, as well as over 200 sketches of her, to the point where the topic became synonymous with his work.

This is his most sensual painting, and his Salome personifies the femme fatale of 19th-century fiction, who was both alluring and deadly. He also associates her with the unrestrained sensuality linked with Eastern femininity in many Orientalist depictions, most notably harem imagery.

The Apparition became his most famous piece, inspiring writers Stephane Mallarme, Gustave Flaubert, and Oscar Wilde, as well as artist Odilon Redon, and inspiring a diverse range of creative and literary renderings of Salome until the early 20th century. Salome became a late-19th-century icon of Orientalism art as a result of Moreau’s depiction, and his work influenced the Decadent and Symbolist movements.

In our globalized society, the concept of stereotyping another culture may appear weird to some, yet it does occur. Traditionally, Europeans and North Americans both saw “the East”, as it was originally known, as an idealized notion. The term “Orientalism art” refers to how Europeans depicted unknown places in the Islamic or Eastern world. Greece, North Africa, and the Middle East were depicted as exotic, fictionalized locales. Orientalism art history reveals the imperialist prism through which Europeans strove to restrict, dominate, and glamorize the history and heritage of the “Orient”. European colonial culture purposefully juxtaposed itself with the Islamic east in order to reinforce a self-fashioned, dominant image.

Take a look at our orientalism painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Orientalism Art?

Orientalism’s definition is the creation of a visual record of locations of importance that were an essential purpose of Orientalist artworks. Such imagery was directed toward a rising audience of North Americans and Europeans who either visited or were interested in seeing the locations. Because steamships and railroads made travel simpler, paintings centered on places like Cairo, Constantinople, and Marrakesh served as destination hubs for both artists and prospective customers. Some photographs featured religious landmarks, both Muslim and Christian, while others recorded pre-Islamic historic sites, such as the pyramid in Egypt. Pictures like this may thus be interpreted as conjuring an exotic Orient.

What Was Portrayed in Orientalist Artworks?

Scenes of ordinary life, whether actual or imagined, piqued the curiosity of Oriental artists. Some depictions concentrated on a single person, while others dealt with a large group. They also ranged from peaceful and meditative images to extremely dramatic situations. The most detailed was maybe sketched from life or revealed the influences of photography, which was a newer discipline. Others were plainly the result of a studio environment, where items from many eras and locations were liberally blended.

What Themes Were Popular in Oriental Paintings?

Scenes of Muslims engaged with their devotion, whether it be at worship, or engaged in their studies in religious school, were central to the Orientalist ideal. Outsiders saw religion as one of the primary distinctions that differentiated them from the peoples of the East. Such images of religion can also be interpreted as a reaction to contemporary fears. European culture and morals were in upheaval, influenced by industry and materialism. During the 19th century, North American and European painters disagreed on how to best depict the world’s many communities.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Orientalism Art – A Detailed Look at Orientalism Art History.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 25, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/orientalism-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 25 August). Orientalism Art – A Detailed Look at Orientalism Art History. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/orientalism-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Orientalism Art – A Detailed Look at Orientalism Art History.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 25, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/orientalism-art/.