“The Third of May 1808” by Francisco Goya – Painting Analysis

War had always been represented as a heroic feat by the academic artists who produced historical artworks. However, this all changed after the creation of The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya. Spanish painter Goya’s Third of May 1808 painting did not render the scene in the idealized fashion of historical art, but instead highlighted the ugly truths of war. This article will explore what made this painting so significant as we investigate The Third of May 1808 painting analysis.

The Significance of The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya

| Artist Name | Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828) |

| Date Completed | 1814 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 268 x 347 |

| Location | Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain |

One of the most well-known Francisco Goya artworks, this painting commemorated the resistance of the Spanish during the occupation of Napoleon’s army in the Peninsula War in 1808. It is a diptych companion piece to another of Francisco de Goya’s paintings, The Second of May 1808. Prompted by a suggestion made by the Spanish painter Goya, the Spanish provisional government of the time commissioned the artworks.

Goya’s Third of May 1808 is regarded as groundbreaking due to its presentation, content, and sheer emotional force, which marked a huge departure from the usual representations of war that focused on the heroes and great deeds. Instead, we see a realistic and dark representation of the victims and bloodshed. Due to it not reflecting any stylistic precedent in its portrayal, it is often regarded as one of the first “modern” paintings. Not only was the subject matter of a revolutionary kind but the entire work was deemed to be revolutionary in intention and execution.

An Introduction to the Spanish Painter Goya

Francisco Goya, considered one of Europe’s last Old Masters, was the most important exponent of Spanish art in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Following his initial involvement in genre painting and religious frescoes, he started developing his etching skills in 1777. As Goya rose to prominence in royal court circles in the early 1780s, he shifted to portraiture, creating his first portraits of royalty, and in 1786 was appointed as the court painter to Charles III. By this point, his customers had grown to include the most affluent members of Spanish society.

Unfortunately, he fell victim to a terrible but undiagnosed sickness in early 1793, which left him totally deaf, introverted, and prone to serious bouts of depression.

The Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808 and the accompanying Peninsula War ended Charles IV’s comparatively liberal monarchy. At this point, Spanish painter Goya was politically ‘uninvolved’. However, his relationship with the reinstated Bourbon king Ferdinand VII, who proclaimed himself absolute ruler and reintroduced the Spanish Inquisition, was strained after the conflict. Goya moved to a farmhouse outside Madrid between 1819 and 1823 and distanced himself from his country’s decline into medievalism. At this point, Francisco De Goya’s paintings became very dark and disturbing in nature.

Background to Goya’s Third of May 1808 Painting

Before we can delve into The Third of May painting analysis, we need to understand the political context in which it was produced. Napoleon became Emperor of France in 1804. Spain was seen as strategically and politically vital for French interests because it regulated and controlled access to the Mediterranean. The reigning Spanish monarch, Charles IV, was viewed by many around the world as an ineffective ruler. Napoleon succeeded in taking advantage of the feeble monarch by proposing that the two countries invade and divide Portugal, with Spain and France each getting a third of the spoils and the other third going to Manuel de Godoy, the Spanish Prime Minister. Godoy succumbed to seduction and agreed to the French offer.

He, however, misjudged Napoleon’s actual intentions and was unaware that his newly acquired ally, the previous king’s son Ferdinand VII of Spain, was taking advantage of the invasion to capture the Spanish parliament and crown.

Ferdinand planned to have Godoy murdered during the imminent struggle for power. In November 1807, 23,000 French soldiers entered Spain unchallenged under the pretense of augmenting the Spanish forces. Even after Napoleon’s objectives became known in February of the following year, the occupying soldiers encountered little resistance except for occasional sporadic attacks. Joachim Murat thought that Spain would benefit from rulers who were more progressive and capable than the Bourbons, and Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, was planned to be crowned king.

After Napoleon persuaded Ferdinand to return Spanish authority to Charles IV, who was then forced to resign in favor of Joseph Bonaparte on the 19th of March, 1808. Even though the Spanish had previously accepted foreign rulers, the new French ruler infuriated them. On the 2nd of May, 1808, the people of Madrid revolted in response to news of the intended deportation of the remaining members of the Spanish royal family to France. The violent revolt resulted in the French troops being commanded to shoot anyone arrested in the uprising. The uprising on the 2nd of May is the topic of Goya’s first painting in the diptych. The Third of May 1808, the most well-known of the pair of Francisco De Goya’s paintings, depicts the French retaliation: before daylight the next day, several hundred Spaniards were picked up and executed in various locations across Madrid.

The Third of May Painting Analysis

Francisco Goya’s Third of May 1808 painting represents a scene from the day after the uprising of the 2nd of May, in the early hours of the morning of the 3rd of May. The artwork features two groups of men, the Spanish that had been captured and the French firing squad. On the right side of the painting is the squad, who are standing in a uniform line with their rifles all pointed at the irregular mass of figures about to be executed on the left. Goya juxtaposed the repetitive linearity of the army’s stance and rifles with the jumbled asymmetry of the group of Spaniards. A lantern had been set between the two groups on the ground, illuminating the scene dramatically.

It brightly illuminates the clustered captives to the left, among whom is a friar and monk in prayer.

Other imprisoned individuals located in the middle right of the painting can be seen standing in line awaiting their fate. The figure in the middle of the group about to be shot is a vividly illuminated man kneeling among the gory remains of those who have already been murdered, his arms extended wide as if pleading to the riflemen. His yellow and white outfit matches the lantern’s hues. His white shirt and sunburned face imply that he is just a common laborer. The firing squad, covered in shadow and depicted as a unified entity, their bayonets, and shako helmets create a persistent and unchanging column when seen from behind.

Most of the squad’s features are obscured, and the individual standing to the right of the man with his arms outstretched, peeking anxiously at the soldiers, functions as a repoussoir, directing our eyes back to the firing squad. A town with a steeple rises in the dark distance without detracting from the intensity of the foreground action. A mob with torches is gathered in the distance between the town and the foreground, either observers, troops, or victims. It is believed that there were originally four Francisco Goya artworks based on the events of May 1808, but that only two that were part of the diptych survived. The absence of two artworks may reflect the government’s discomfort with the representation of a public rebellion.

The Iconography of Goya’s Third of May 1808

Art historians and critics initially had very mixed feelings about this painting. Previously, artists had preferred to represent warfare in the style of historical painting, and Francisco Goya’s unheroic account was extremely uncommon at that time. Some early critics thought the artwork was also technically flawed: they felt that the perspective was too flat and that the captives and the executioners were positioned too close together to be considered lifelike. Although these criticisms are legitimate, writer Richard Schickel contends that Spanish painter Goya’s goal was not academic accuracy, instead attempting to enhance the overall effect of the painting.

The painting alludes to several earlier pieces of art, but its strength stems from its directness instead of its adherence to established compositional formulae.

An epic depiction of unadulterated violence replaces artistic fabrication. Even contemporaneous Romantic artists, who were similarly interested in issues like injustice, conflict, and death, structured their works with a stronger emphasis on aesthetic expectations. The artwork is also thematically and structurally linked to Christian art martyrdom traditions, as seen by the intense application of chiaroscuro and the desire to live contrasted with the certainty of impending execution. However, Goya’s work deviates from this tradition. Paintings depicting violence, such as those by Jusepe de Ribera, combine an artistic approach and a harmonic arrangement to foreshadow the victim’s “crown of martyrdom”.

The figure with outstretched arms at the composition’s focal point has been likened to a crucified Jesus, and an analogous posture may be found in portrayals of Christ’s nighttime Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane. Goya’s figure bears stigmata-like markings on his right hand, and the lamp in the middle of the painting alludes to the Roman troops who seized Jesus in the garden. Not only is he poised as though in crucifixion, but he also wears the papacy’s heraldic colors of white and yellow. The lantern was commonly used as a means of illumination in art by Baroque painters, and it was mastered by Caravaggio. Traditionally, a dramatic light source and the resulting chiaroscuro were employed to represent God’s presence.

Illumination by torchlight or candles acquired religious implications; nevertheless, in Goya’s painting, the lantern performs no such miracle. Instead, it offers light just so that the shooting squad may finish its horrible task, and so that the observer can observe the wanton carnage. Light’s traditional significance in art as an instrument for the spiritual has been undermined. The victim is as nameless as his assailants. His plea is directed not to God, as in conventional artworks, but to an unsympathetic and indifferent firing squad. He is not given the heroism of individuality but is only a victim in a chain.

A bloody and mangled body lays underneath him; behind and all around him are other people who will soon suffer the same fate.

According to historian Fred Licht, dignity in individual sacrifice is substituted here for the first time by hopelessness and meaninglessness, being the victim of mass murder, and lack of identity as an aspect of the modern condition. The way the artwork depicts the passage of time is also unique in Western art. Traditionally, the passing of an innocent victim was depicted as suffused with the ideals of heroism. There is no such cathartic message in this painting, though. Rather, it represents the mechanical formalization of murder, there is a continual procession of the convicted. The inevitable result is shown in the lower left section of the painting, where a man’s corpse is sprawled on the ground. There is no place for the sublime; the corpse’s torso and head have been deformed to such an extent that resurrection is inconceivable.

The sufferer is shown to be devoid of any spiritual grace. The audience’s eye level is generally along the center horizontal axis for the remainder of the image; only here is the perspectival viewpoint modified so that the audience looks down on the corpse. Finally, the Spanish painter Goya makes no attempt to lessen the subject’s savagery by means of technical competence. The technique and the subject are inseparable. Goya’s approach is guided less by traditional standards of skill and more by the horrific subject matter. The brushwork is unappealing, and the colors are limited to earthy hues and black, accentuated by flashes of white and the victims’ red blood.

The pigment’s quality hints at Goya’s later artworks: a granular solution with a matte, sandy finish. Few would praise the painting for its artistic flourishes, given its terrifying intensity and absence of theatricality.

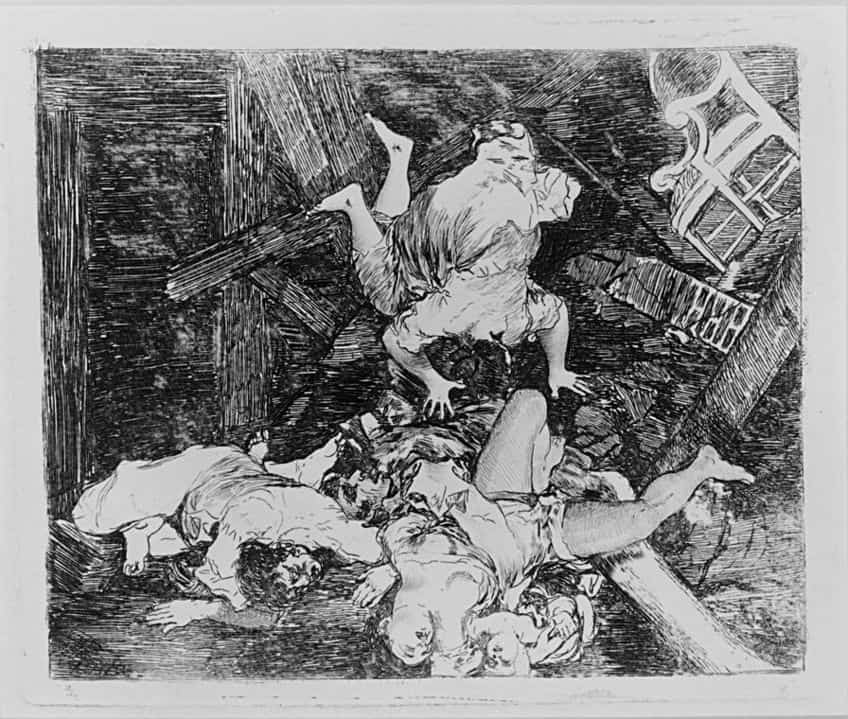

Francisco Goya’s Artworks: The Disasters of War

This series of etchings by Goya was only completed in 1820, with the majority of the prints produced between 1810 and 1814. However, the album of proofs provided to a friend by Goya, which is now housed in the British Museum, has several clues as to the sequence in which both the preliminary sketches and the final prints themselves were made. The oldest sketches appear to predate the commission for the diptych paintings and contain two prints with unquestionably related themes.

One Cannot Look at This is obviously connected thematically and compositionally; the figure in the center has her arms outspread but pointing downward, another figure has his hands folded in prayer, and numerous others conceal their faces.

Only the bayonets of the troops’ firearms are visible this time, even from behind. And It Cannot Be Helped is yet another of these early prints, from a somewhat later group presumably made during the height of the conflict when resources were scarce, forcing Spanish painter Goya to remove the plate of an earlier landscape print in order to make this and another work in this series. It depicts a shako-clad shooting squad in the background, this time pictured from the front instead of the back.

Provenance

Despite the work’s historical significance, no information about its first exhibit is available, and it is not referenced in any extant contemporaneous sources. This absence of critique might be attributed to Fernando VII’s taste for neoclassical artwork, as well as the restored Bourbons’ disdain for popular revolts of any type as appropriate subject matter. A monument commemorating the slain in the rebellion, likewise commissioned by the temporary government in 1814, was halted by Ferdinand VII, who despised the heroes of the war for independence because of their reformist aspirations.

According to some sources, the artwork was stored for 30 to 50 years before it was displayed to the public.

The artwork was still the property of the government or monarchy, as evidenced by its inclusion in an 1834 Prado inventory; as most of the royal collection had been given to the museum at its founding in 1819. During a visit to the museum in 1845, Théophile Gautier remembered observing “a massacre” by Francisco Goya, and a visitor in 1858 also noticed it, although both reports refer to the painting as showing the events of the 2nd of May, not the 3rd. The work of art was considered important enough by Goya’s biographer Charles Emile Yriarte in 1867 to deserve its own special exhibit, although it wasn’t included in the Prado’s official catalog until 1872.

Sources

Popular iconography, posters, and broadsides were most probably sources of inspiration for the painting. During the Napoleonic War, representations of firing squads were prominent in Spanish political iconography, and Goya’s adaptations imply that he envisioned heroic-scale works that would be appealing to the broad people. The Assassination of Five Monks from Valencia, by Miguel Gamborino, is said to have served as a basis for Goya’s composition.

Similarities included a victim in a crucifixion stance, distinguished by his white robe; a monk with clenched fists kneeling to his left; and an executed body lying in the foreground.

The composition’s geometry might be an ironic reference to the painting Oath of the Horatii (1784) by Jacques-Louis David. The outstretched arms of the three Roman Horatii in salute in David’s painting become the guns of the firing squad, while the father’s upraised arms represent the victim’s posture as he confronts his executioners. While David’s figures’ emotions are rendered in a neoclassical style, Goya’s response is rendered in stark reality.

Legacy

Many subsequent artists were influenced by Francisco De Goya’s paintings about the events of May 1808. Édouard Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximilian, painted in numerous iterations between 1867 and 1869, was the first interpretation of Goya’s work. Manet was influenced by Goya’s painting and may have seen it at the Prado Museum in 1865 before starting his own artwork, which was regarded as too sensitive in subject matter to be shown in France during Manet’s lifetime.

Picasso’s Massacre in Korea, painted during the Korean War in 1951, bears an even more blatant similarity to Goya’s Third of May painting. The offenders in this picture were meant to represent members of the US Army or their UN allies. Aldous Huxley said in 1957 that Goya did not possess Rubens’ ability to fill the canvas with an orderly composition, but he regarded The Third of May 1808 as an achievement since Goya was communicating in his native visual language, allowing him to express himself with maximum intensity and clarity.

The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya is regarded as one of the first truly modern paintings due to the realistic portrayal of warfare, as opposed to the idealized depictions of heroism that were previously popular. We observe a row of French troops leveling their weapons at a Spanish individual, who extends his arms in surrender to his fate. A rural hill behind him serves as an executioner’s wall. A heap of dead bodies, dripping in blood, lays at his feet. A line of Spanish insurgents reaches into the distance on the opposite side. They close their eyes to avoid seeing the death that they know is coming. Even a monk kneeling in prayer will soon join the ranks of the dead.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Unique About Goya’s Third of May 1808 Painting?

The academic art world tended to favor classical historical artworks. These works focused on representing the dead as heroes and were not usually gruesomely depicted. Goya, though, painted his works in dreary and somber colors and made the dead look truly horrific. He decided to show what war was really like and not sugarcoat the subject.

What Is Portrayed in The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya?

This painting depicts the events that followed the Spanish uprising against the French on the 2nd of May 1808. The French troops were commanded to round up all of the rebellion and execute them. In the painting, we can see a long line of Spanish people awaiting their death as a group is fired upon by a French firing squad.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, ““The Third of May 1808” by Francisco Goya – Painting Analysis.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. June 21, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/the-third-of-may-1808-by-francisco-goya/

Anthony, J. (2023, 21 June). “The Third of May 1808” by Francisco Goya – Painting Analysis. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-third-of-may-1808-by-francisco-goya/

Anthony, Jordan. ““The Third of May 1808” by Francisco Goya – Painting Analysis.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, June 21, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-third-of-may-1808-by-francisco-goya/.