Vanitas – Explore the History and Style of Popular Vanitas Art

What is Vanitas art and what does it represent? Let us start with a Vanitas art definition: Vanitas paintings portray specific objects arranged in still-life style, and each of these objects has been added as a reminder of the impermanence of earthly delights. Vanitas still-life artworks rose to prominence from the 16th century onwards, and can even be found in modern art.

What Is Vanitas Art?

The Dutch Golden Age witnessed an extraordinary outburst of artistic creativity. This era in Dutch history saw the rise of artists such as Johannes Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Frans Hals. The topics of Dutch master artworks tended to be historic, portraits, and household interiors, with underlying themes for the audience to analyze.

Yet, a genre of still-life art called Vanitas grew more fashionable throughout this time period, despite the fact that we have little to no Vanitas paintings by the Master artists named above.

Vanitas still-life paintings were created during a period of tension regarding religion as a symbol for the Protestant goal of self-contemplation. Casting off their Catholic Spanish masters, the Dutch Nation had become a proudly protestant society and attempted to portray this attitude through their Vanitas paintings.

The History and Concepts of Vanitas Paintings

Vanitas paintings grew in popularity from roughly 1550 until around 1650. They originated as still lifes that were created on the backsides of portraits as an express reminder to the sitter, and eventually developed into prominent artworks of their own.

The group was based in Leiden, a Protestant center, but it spread all through the Netherlands as well as regions of Spain and France.

The Religious Roots of Vanitas Still-Life Paintings

There was a radical change in religious philosophy brought about by the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s. As Europe fragmented itself into Catholic and Protestant factions, many religious concerns that were a hallmark of the Early Medieval mentality grew even more complicated. Throughout this time, there emerged a trend toward iconoclasm, which was aided by the Catholics.

Protestants thought that imagery may be helpful in comprehending God and spiritual concerns.

In contrast to Catholicism’s group prayer, Protestantism encouraged a more individualized attitude to reflection. This individualized approach toward introspection, as well as the concept that imagery may function as a guide for consciousness, aided the Dutch master’s creativity in producing Vanitas paintings. Because the Dutch Republic was Protestant in the 1600s, there was an outflow of this contemplative kind of art. It is unlikely that this subgenre would have gained popularity if not for Calvinism and the Counter-Reformation.

Both movements, one Protestant and the other Catholic occurred around the same time that vanitas works were popularized, and experts today view them as warnings against the pleasures of life and representations of the Calvinist morals of the era.

The Realism of Vanitas Still-Life Paintings

Vanitas paintings were a creative response to Catholic counter-reformational art. The mythology of martyrs of the Catholic religion was central to Counter-Reformation artwork. Vanitas still-life art, on the other hand, is pragmatic and anchored on worldly matters, as opposed to Catholicism’s ethereal perspective.

Vanitas art encourages one to direct one’s attention toward the Heavenly Kingdom through what can be found here in the earthly realm.

Vanitas artworks are incredibly intricate, and close scrutiny demonstrates the artist’s talent and realism. The naturalism of Dutch masterworks emphasizes items from the audience’s life, making the images relevant. Vanitas effectively insulates its core ideas, the vanity of worldly things, by employing a realistic aesthetic.

The complexity and ephemeral characteristics of worldly existence are clearly depicted in artistic realism.

The Disordered Arrangement of Vanitas Artworks

When first viewing a Vanitas artwork, it can seem extremely disorganized. The canvas is crammed with somewhat arbitrary items. Yet, not only are the pieces significant but so is the artistic decision to assemble them in this way. The Dutch master artworks provide a metaphoric depiction of the world’s vulnerability.

Nothing will last, and nothing is able to withstand deterioration and our eventual passing.

It is a solemn message intended to influence its audience. Vanitas art can be seen as a Protestant morality teacher. Vanitas informs us of the temptation of material possessions and how transient and unsatisfying they are in comparison to Heaven.

Its purpose is to urge the observer to behave in line with the Lord and the Heavenly Kingdom.

Vanitas Symbolism

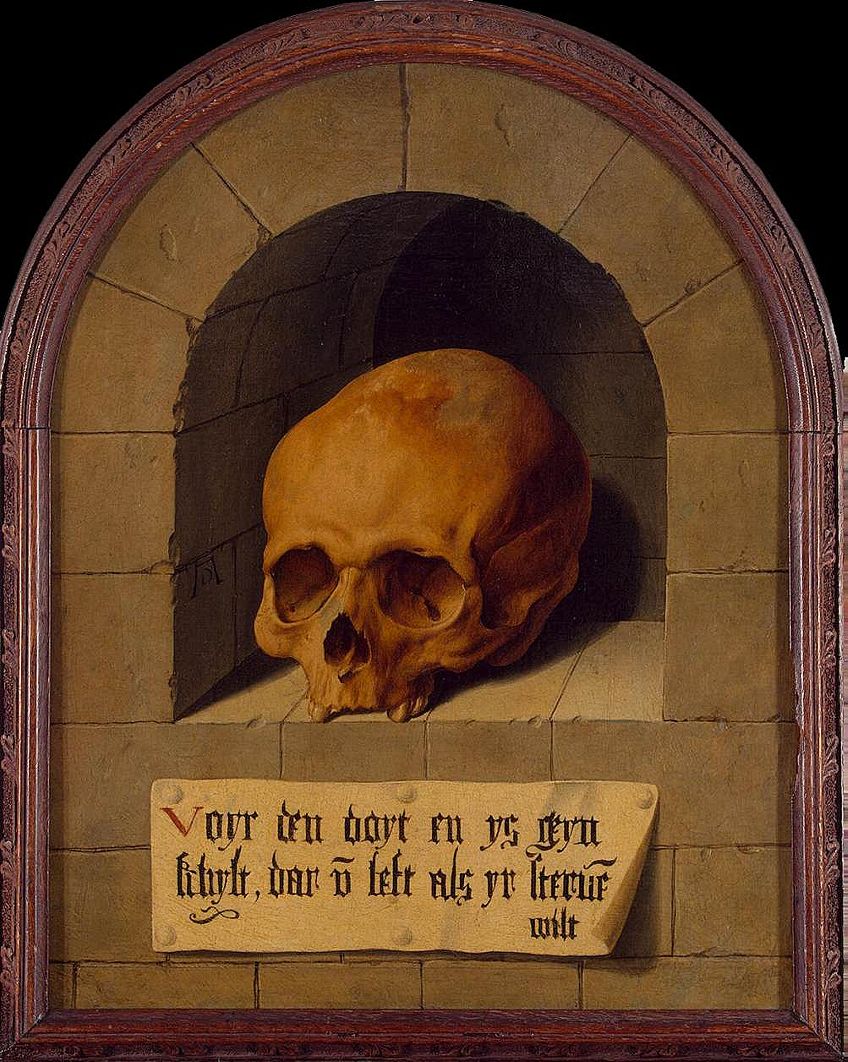

A vanitas artwork, despite including beautiful items, always contained an allusion to man’s impermanence. Most commonly, this includes a human skull, however, objects such as blazing candles, soapy bubbles, and withering flowers could also be incorporated. Additional elements in Vanitas still lifes are used to represent the numerous forms of materialistic desires that seduce mankind.

A vanitas artwork may incorporate allusions to time, for example, an hourglass, in addition to the skull to represent mortality. It may also utilize decaying blossoms or spoiled food for this same reason.

Certain symbols of knowledge, that can be observed in the sciences and arts can be represented through textbooks, charts, or instrumentation, for example. Gold, jewels, and expensive ornaments are emblems of power and wealth, whilst textiles, pipes, and goblets may indicate worldly pleasures.

The notion of rebirth is also reflected in certain artworks, by including objects such as laurel or stalks of grain. Art historians argue about how frequently and how severely the vanitas motif is indicated in still-life paintings that lack clear iconography like a skull.

The pleasure elicited by the visceral representation of the theme, like in most strongly moralistic genre paintings, is at odds with the puritan message.

Vanitas Artists and Their Artworks

Vanitas still-life paintings were quite dreary and dark at the start of the movement. Yet, towards the end of the era, it did liven up a little. The essence of vanitas artworks became that, while the cosmos is oblivious to human existence, the world’s grandeur might be appreciated and explored.

A handful of painters were well-known for their vanitas work, which was regarded as a defining style in Dutch Baroque painting.

Dutch artists such as Harmen Steenwijck, David Bailly, and Willem Claesz Heda are among them. Several French artists, with the most well-known of them being Jean Chardin, also produced works in the popular vanitas style. Below we will be taking a look at some of the most famous Dutch artists of the Vanitas period.

David Bailly (1584 – 1657)

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Date of Birth | 1584 |

| Date of Death | 1657 |

| Place of Birth | Leiden, Netherlands |

David Bailly was born in Leiden, the Dutch Republic, and his father was a calligrapher named Peter Bailly. David Bailly worked as a draftsman for his family and was the apprentice of Jacques de Gheyn, a copper engraver. David Bailly then studied with Adriaan Verburg, a painter and surgeon in Leiden, and then subsequently went on to apprentice in Amsterdam with portraiture artist Cornelius van der Voort.

Bailly undertook his Grand Tour in the winter of 1608, visiting Nuremberg, Frankfurt, Augsburg, Hamburg, Venice, and Rome.

After returning, he spent the next five months in Venice, laboring as a freelancer wherever he could until traversing the alps in 1609. Bailly served numerous German nobles on his return journey, notably the Duke of Brunswick. Bailly started to paint still-life themes and portraits upon his arrival in the Netherlands in 1613, comprising portraits of his pupils and instructors at the University of Leiden.

He is well-known for his vanitas works, which represent the ephemeral nature of existence using symbols that portrayed the transitory nature of life such as blossoms and candles.

Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols (1651) by David Bailly

| Date Completed | 1651 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Dimensions (cm) | 65 x 97 |

| Current Location | Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden |

The line between the still-life genre and portrait genre is dissolved in this vanitas still-life. On the still-life side of the painting, there are multiple portraits (as paintings inside of a painting) arranged on the table as elements of a still-life composition. A skull, a snuffed candle, money, a spilled wine glass, a watch, flowers, a necklace, books, a pipe, and art are among the items in the composition.

As a sign of fragility, soap bubbles float over them.

On the portrait side of the painting, the overall visual ensemble acts as a commentary about the youthful man depicted to the side of the objects, whose face bears the conventional traits of a self-portrait. It may consequently come as a surprise that Bailly was actually 67 years old when he produced this image in 1651. The issue of which genre it falls under is resolved, however, when we notice that his actual characteristics are depicted in the little oval picture, demonstratively thrust out to the audience – the picture itself a technique that already captures the transience of existence.

The younger artist’s visage, on the other hand, depicts Bailly at a younger age, more than 40 years ago. Therefore, by shifting the time frames of past fabrication and actual reality, the artwork implies that the youthful artist is foreshadowing his eventual age, which, while part of the current moment as it was in 1651, seems to relate to the past, as represented through the means of the portrait.

The young person, who looks to be so realistic within the painting, actually depicts a past state.

Clara Peeters (1594 – 1657)

| Nationality | Flemish |

| Date of Birth | 1594 |

| Date of Death | 1657 |

| Place of Birth | Antwerp, Belgium |

Although specifics about her life are scant, records show that Clara Peeters was christened in Antwerp in 1594 and also married there in 1639. There is no evidence that Peeters ever belonged to the Antwerp Artists’ Guild, although documents for several years are lost. The first documented oil paintings by Peeters, from around 1607, are detailed representations of beverages and food.

The proficiency with which this young painter produced such images suggests that she was schooled by a master painter.

Despite the lack of formal proof, researchers assume Peeters was a pupil of Osias Beert, a well-known Antwerp still-life artist. By 1612, Peeters was making a huge number of finely produced still lifes, most of which included groups of precious things such as beautifully adorned gold coins, metal goblets, and exotic flowers.

Her works frequently depict similar formations on small ledges from low viewpoints, against dark backdrops.

Still Life with Flowers (1611) by Clara Peeters

| Date Completed | 1611 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 52 x 73 |

| Current Location | Museo del Prado, Madrid |

This panel is a medley of materials, textures, reflections, and a variety of colors that requires careful examination. Patience is a characteristic linked with female artists. Indeed, Peeters labored diligently in her numerous minutely portrayed still lives that became enormously famous in her home Holland as well as elsewhere in the first half of the 17th century, producing 31 pieces that reflect her unique style.

Peeters, like numerous other women who produced flowers, seems to be influenced by scientific observation, notably the legacy of illustrated herbals, which provided women with motifs for the customary feminine pastimes of needlework and lace crafting.

She shared this connection between her artistic endeavors and early scientific findings with a number of her female contemporaries, including those associated with the “Academy of the Lynx-eyed,” which was created in Rome in 1603. These schools emphasized the value of patient observation over periods before producing a picture on canvas.

This attentiveness, this patience, was likely key to most of the work created by women at the start of the 17th century.

Nature was studied over time and meticulously, methodically, and slowly depicted. To return to Clara Peeters’ picture – dealing with time in a variety of ways, her artwork depicts a fleeting moment while simultaneously implying nature’s immortality. It demonstrates the wealth of possessions, but also, maybe, the certainty of death.

Willem Claesz Heda (1594 – 1680)

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Date of Birth | 1594 |

| Date of Death | 1680 |

| Place of Birth | Haarlem |

Very little is known about the life of Willem Heda. He spent his whole life in Haarlem, where he entered the St Luke’s guild and rose through the ranks. Heda produced some figure drawings early in his career but ultimately focused only on still lifes. Heda was a genius at representing reflecting light on smooth, shining surfaces like silver, pewter, or brass candelabra. He frequently painted the same objects in many works, which were dubbed “breakfasts”.

His oldest recorded piece was a Vanitas, which suited the monochrome and skilled textures of his later paintings but depicted a subject matter separate from his subsequent portrayals of more luxurious things.

This Vanitas, as well as two other breakfast artworks by Heda in the 1620s, were notable for their marked departure from prior breakfast paintings. Notwithstanding the irregular and diagonal arrangement of items, the objects in these paintings display a greater impact and preserve a feeling of equilibrium for the observer.

Furthermore, in contrast to early breakfast pieces, these newer works followed a monochrome approach. After his developmental works of the 1620s, Heda attained his creative peak in the 1630s with his works and those of the “1639 group,” which were sold in Vienna in the 1930s. In combination with the presented delicacies, these items comprise nicely draped cloth and a variety of exquisite glass and metal objects. This body of work is distinguished by a sublime elegance and order achieved by few painters in his field.

His use of lighting and color in the compositions, along with precise additional brushwork, resulted in an amazing degree of realism.

Still Life with Gilt Cup (1635) by Willem Claesz Heda

| Date Completed | 1635 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 88 x 113 |

| Current Location | Rijksmuseum |

It wasn’t until the 16th century that artistic depictions of meals, flowers, or other domestic items began to emerge as a distinct genre. Previously, still-life pieces emerged as a feature of works devoted to other topics, such as metaphorical and biblical themes.

Heda was well-known for his depictions of food, particularly bread, fish, and other items commonly consumed towards the morning’s end.

Several art historians have suggested that such images may have symbolic value, such as a caution against over-indulgence, but some believe Heda regarded them as a chance to showcase his magnificent ability to portray diverse textures and produce expressionistic effects.

The meal in question is lavishly decorated with costly silverware, oysters, and seasonings.

Heda primarily employed moderate tones, except occasional color highlights, such as the yellow skin of the lemon or the gilded cup. This almost-monochrome scheme creates a sense of oneness, while the purposeful disorder of the elements and the placement of the two plates, which appear to be on the verge of falling off the table, add to the impression of depth.

Judith Leyster (1609 – 1660)

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Date of Birth | 1609 |

| Date of Death | 1660 |

| Place of Birth | Haarlem, Netherlands |

Judith Leyster created the majority of her works between 1629 and 1635; her creative productivity dropped considerably following her engagement in 1636. It is believed that Judith Leyster may have handled her family’s business and assets in addition to rearing her children, and she may also have aided with her husband’s painting.

By 1649, the family had relocated from Amsterdam to Haarlem, where she would spend the rest of her life.

Her artwork was definitely influenced by the genre works of famed Haarlem painter Frans Hals, which resulted in authorship mistakes. Leyster and her art were mostly disregarded after her death until 1893 when an artwork bought by the Louvre was discovered to include Leyster’s characteristic monogram (her initials interwoven with a five-pointed star) concealed behind a fraudulent signature reading “Frans Hals.”

This revelation sparked increased interest in and admiration for Leyster’s work, which had earlier been mistaken with Hals’.

The Last Drop (1639) by Judith Leyster

| Date Completed | 1639 |

| Medium | Oil painting |

| Dimensions (cm) | 89 x 73 |

| Current Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

The artwork’s seeming simplicity is startling, yet a closer glance exposes visual complexity under the surface, which gives rise to a sophisticated underlying concept. Leyster eventually used her work to advise viewers against a life of excess and vice, notably through visual contrast, purposeful body posture, illusionistic naturalism, and color.

The strong juxtaposition between the illuminated knight and his silhouetted partner, as well as the blazing candle and the black hourglass, is the first thing a person observes about this painting.

The light accentuates the texture and colors of his attire, as well as the nuances of his cheerful demeanor. In this way, the cavalier’s character shines through more than his companion’s. He is the quintessential picture of a 17th-century gentleman indulging in society’s vices – excessive drinking, smoking, and engaging in frivolous conduct. His partner, though, sits in the shadows, hidden from view by a wall of shadow.

In contrast to his companion, his personality is not fully expressed. He partakes in the same joy as the cavalier, but the darkness that envelops him makes his actions appear less insignificant, less humorous. He represents the “evil side” of excess; the visual contrast of the friend against the cavalier shows both the happy facade of a careless lifestyle as well as its less appealing outcomes. The shadowy hourglass contrasting the candle is another key contrast established by Leyster in this painting.

According to one explanation, the skeleton brought the light to expose the hourglass so that the person on the left might realize that time is running out.

The dimming of the hourglass suggests that it has been pushed as much into the figure’s vision as allowed, but he still decides to ignore it. Death has tried so hard to deliver its warning that it has accidentally veiled its own message from view. The candle provides another reminder of the character’s refusal to accept his fate. Because it is difficult to disregard something as bright as light, the character’s seeming denial of the light’s presence demonstrates that he is averse to the reality that he is being presented with.

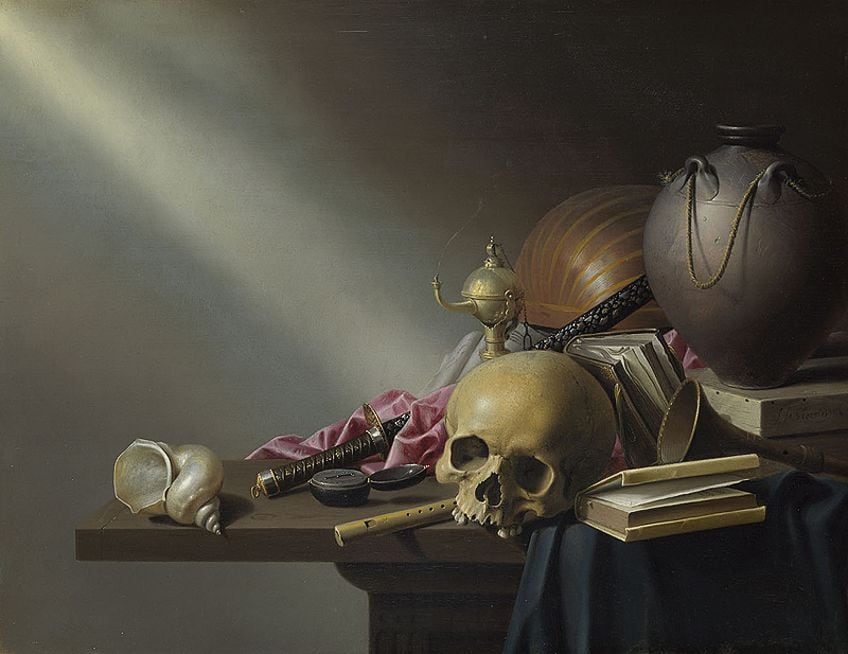

Harmen van Steenwyck (1612 – 1656)

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Date of Birth | 1612 |

| Date of Death | 1656 |

| Place of Birth | Delft, Netherlands |

Harmen van Steenwyck, a famous Dutch artist of the Leiden movement, was a master of still-life painting in the 17th century, and Vanitas still-life paintings were his specialty. In 1612, Steenwyck was born in Delft. It is also the hometown of Jan Vermeer, another well-known Dutch Golden Age painter. David Bailly, his uncle, initially taught him how to draw. He was tutored by his uncle for five years beginning in 1628.

He eventually collaborated with his renowned brother Pieter to start running an art workshop. In 1636, he joined the Guild of Saint Luke, enabling him to admit students.

By 1654, he is a well-known artist and a leading representative of vanitas still-life art. Harmen van Steenwyck’s works were notable for their golden palette, dramatic color tonal variations, and incredibly fine and imperceptible brushwork. He was skilled in portraying the varied effects that light had on distinct surfaces as well as expressing an almost glowing, lifelike, and piercing aspect on some of his compositions’ items.

Such as with the works of Gerrit Dou and Jan Lievens, the objects in his works, notably fruits, were rendered in meticulous detail.

A Vanitas Still Life with a Bust (c. 1650) by Harmen van Steenwyck

| Date Completed | c. 1650 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 60 x 81 |

| Current Location | Rafael Valls |

This piece has several similarities to Steenwyck’s Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities (c. 1650), particularly the unusual oil lamp and the sword. The sword is identical to that seen in Pieter Steenwyck’s Vanitas Still Life from 1654. Bredius classified the blade as being Eastern in style, while Bergström said it was likely North African, and E. de Jongh thought it could possibly be a ‘Hartsvanger,’ a type of blade commonly used by maritime commanders.

The influence of the older David Bailly works may be seen in Steenwyck’s ornate vanitas, notably in the monochromatic aspect of the palette.

This shows that both painters stayed in touch after Steenwyck finished his studies with Bailly, presumably due to familial ties. The sculpture in the painting is by Barthélemy Prieur, and the bust piece is from the Laocoön group, which is among the best-known Roman artworks in history and is currently housed at the Vatican museum.

Evert Collier (1642 – 1708)

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Date of Birth | 1642 |

| Date of Death | 1708 |

| Place of Birth | Breda, Netherlands |

Collier received his training at Haarlem, where his early projects reflect the influences of Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne. When Collier joined the Haarlem guild in 1664, Van der Vinne was most likely his tutor. Both had an impact on the still-life artist from Haarlem, Barend van Eisen. The artist had relocated to Leiden by 1667, and in 1673 he had become a participant in the Leiden Guild of St. Luke.

He relocated to Amsterdam in 1686 and then once again in 1693 to London.

Based on dated and signed paintings, he relocated to Leiden around 1702, but towards the final stage of his life, he once again returned to London, where he eventually passed away and was buried on the 8th of September, 1708 at St. James’s. His paintings are often composed of an assemblage of paper pieces that “jump out” of the canvas.

Like Van der Vinne preceding him, he frequently incorporated prints, although they were usually popular works of the time.

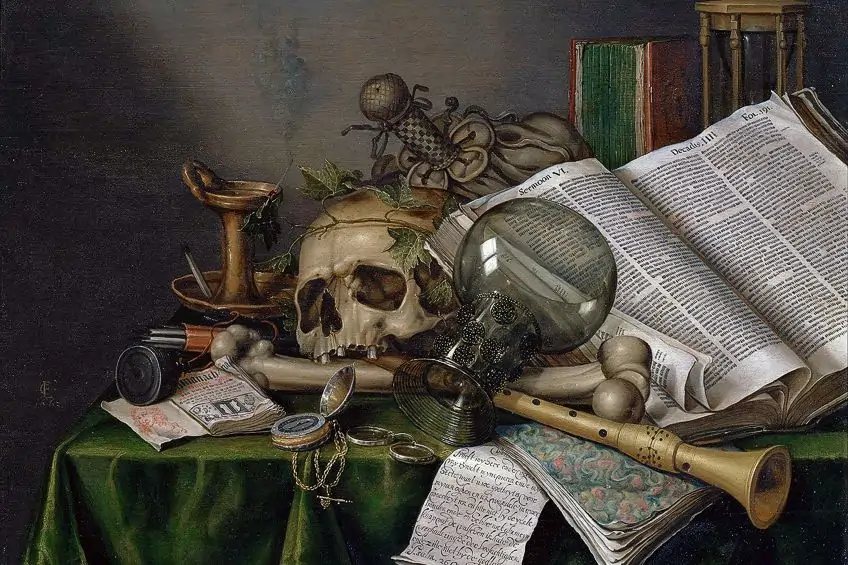

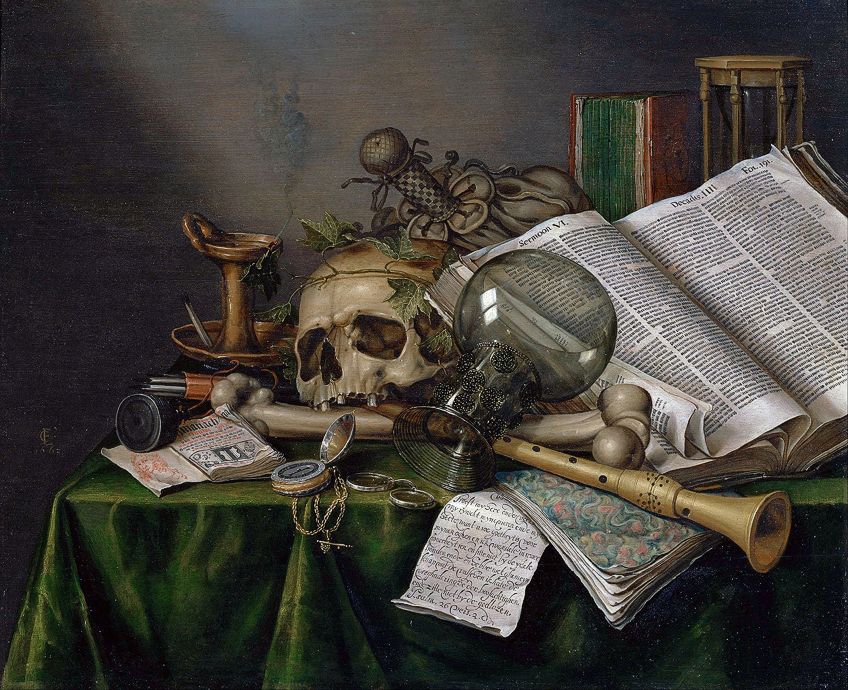

Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull (1663) by Evert Collier

| Date Completed | 1663 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 56 x 70 |

| Current Location | National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo |

At first glance, the items appear to be positioned randomly, but it quickly becomes clear that the composition was precisely established along the two diagonals. In this artwork, we can clearly observe the traditional Vanitas symbols of impermanence.

These include a skull, a burnt-out candle, a timepiece, and various books and manuscripts.

Each of these objects was carefully placed on the table – not just for their aesthetic value, but also for the deeper meanings inherent in each object symbolically. Two timepieces are visible in the work: the first is a pocket watch placed in front of the skull, and the other is an hourglass that can be seen behind the books to the right of the image.

As we have observed in this article, Vanitas artist strove to create works of art that reminded the observer that life was not to be taken for granted or abused. Vanitas paintings featured assemblages of artifacts that represent the certainty of death, as well as the ephemerality and folly of worldly triumphs and delights; it obliges the spectator to ponder death and repentance. Throughout the late Renaissance, simple images of skulls and other emblems of mortality and ephemerality were regularly depicted on the back sides of portraits. These were to remind the sitter of the portrait that their vanity was truly in vain.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Vanitas Art?

Vanitas paintings are a kind of still-life painting that is specifically designed to warn the observer of the fleeting nature of life and the pointlessness of transitory desires. Skulls, burning and snuffed candles, manuscripts, withered flowers, alcohol, and musical equipment are among the things used in Vanitas artworks to inform audiences of their own inescapable fate. The book’s symbolism typically relates to false pride gained through knowledge. The wine jug relates to the fleeting nature of some indulgences, such as excessive food and alcohol consumption.

What Is the Vanitas Art Definition?

Vanitas still-life paintings blossomed in the Netherlands as Dutch artists responded to the period’s growth in luxury. Vanitas painting was created to convey the transitory, fleeting, and finite character of existence via the use of common and identifiable symbols. Vanitas still-life paintings use symbolic items to remark on the temporary aspect of earthly possessions and the certainty of death. Card decks, maps, books, wilting flowers, food, jewelry, goblets of wine, hourglasses, skulls, and recently burned candles are common motifs in vanitas paintings, which generally depict prosperity and death. Ivy sprigs, laurel leaves, and corn ears are also emblems of perpetual life and rebirth.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Vanitas – Explore the History and Style of Popular Vanitas Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 12, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/vanitas/

Anthony, J. (2022, 12 August). Vanitas – Explore the History and Style of Popular Vanitas Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/vanitas/

Anthony, Jordan. “Vanitas – Explore the History and Style of Popular Vanitas Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 12, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/vanitas/.