Viking Art – The Exciting World of Viking Culture and Norse Art

The terms “traditional Viking art” and “Norse art” are used to describe the works of the Scandinavian seafarers who settled in regions such as Iceland and the British Isles from the 8th to the 11th centuries. The Vikings’ history is entangled with that of many cultures; therefore, Viking design shares many characteristics with Germanic, Celtic, and Romanesque artworks. What we know today about Viking culture is based largely on what we learned through the examination of certain Viking artifacts made from materials such as stone, metal, wood, ivory, and bone. However, the Viking concept of art is still not yet fully understood, but we can get a significant amount of knowledge by examining the Viking artworks and Norse artworks that we have so far uncovered.

Exploring Traditional Viking Art and Norse Art

While the Viking culture originated in Scandinavia, they are most known as the seafaring people who sailed the seas in search of lands to plunder and inhabit. Although this is true, it does not mean that they were complete savages, and the intricate Norse knotwork and Traditional Viking artworks prove how creative and skilled they were as craftsmen and artists.

The Vikings’ history of plundering was infamous, and the many artifacts found strewn across Europe and other lands just go to prove how effective the Viking culture was.

When we think of art, we usually think of great classical masterpieces exhibited on museum walls. The notion of “art for the sake of art” is nothing new. Yet, as you can expect, that’s not exactly Viking style. Viking art is largely made out of “things”. A scene of the Norwegian highlands will not be found in a gallery like other cultures’ works.

Instead, the Vikings decorated commonplace goods with beautiful craftsmanship and carving.

The artistic heritage dates back to intricate sculptures portraying serpents and monsters battling and continues to the present day. Because of the worldwide interest in Viking culture, there is a growing collection of imitation artifacts and fan Viking concept art from the period.

Religious Impact on Norse Artwork

Religion, rather than political or financial factors, had the largest influence on Viking art. Scandinavia was largely pagan in the 9th century, and its inhabitants worshiped pagan gods like Thor, Odin, and Frey. They regularly, if not always, practiced inhumation, burying their deceased beside a diverse range of burial items.

A ship, either actual or metaphorical, was frequently linked with the cemetery, transporting the deceased on his spiritual voyage.

Regrettably, for archaeologists, the arrival of Christianity put a stop to the possession of burials, but the Vikings proceeded to bury silver and gold hoards. Christianity spread in Scandinavia for a wide range of reasons, such as the missionary activities of priests like Poppo and Ansgar, as well as monarchs’ political aspirations. Thus, King Olaf’s endeavors to convert Norway were inextricably related to his goal to become the only ruler of the land.

Denmark was Christianized by King Harold Bluetooth, Norway by Anglo-Saxon missionaries in the early 12th century, and Sweden by the late 12th century.

Where to View Norse Artworks

Many museums in Scandinavia and the rest of the world have some examples of Viking artwork. Viking artifacts are quite popular and in high demand for exhibition. Runestones are often found where they were unearthed rather than being relocated so that they may be viewed across the Nordic nations.

The Osberg ship and most of its components are on exhibit in the Viking Ship Museum in Bygdoy, which is part of the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History. The museum also exhibits the ship as well as a large portion of the burial items from the Borre mound cemetery.

The National Museum of Denmark has a vast collection of Viking and Norse art, including those discovered in the Mammen tomb. The Urnes Stave Church still maintains most of its historic wood decorations and is open to the public. Since 1881, it has been held by the Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments. It is still used as a church for special events but no longer performs regular services.

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has a limited collection of Viking artifacts on exhibit, primarily brooches. They also include several Vendel-era antiques and some fascinating Tiffany & Co. Viking-inspired pieces.

Materials Used by the Viking Culture

While regional influences are typically prominent outside of Scandinavia, and the history of the formation of styles can be less evident, Viking artwork or Norse artwork is usually grouped into chronological categories. But before we explore the various Norse art periods, we will take a look at the various materials that were commonly used in Viking culture. The Norse artworks that remain today are mostly in the form of durable materials such as metal, wood, and stone, as these are less susceptible to deterioration over time.

Wood and Other Organic Materials

Wood, which was reasonably easy to cut, affordable, and plentiful in Northern Europe, was probably the main medium of choice for Viking craftsmen. Stunning examples of wood artwork at the start and end of the Viking era, particularly the 9th-century Oseberg carvings of the burial ships and the 12th-century carved ornamentation of the Urnes Stave Church, highlight the value of wood as an artistic material in Viking culture.

According to one archeologist, “these amazing relics allow us to develop at least a sense of what we are lacking from the entire body of Viking artwork.”

Additionally, wooden remnants and small-scale carved Norse artworks in other materials such as amber, antler, and walrus ivory give further clues. The same is undoubtedly true of the textile arts, even though embroidery and weaving were well-developed crafts.

Stone

The next material used in Norse artwork is stone. Stone carving was not practiced anywhere else in Scandinavia until around the mid-10th century and the construction of the royal memorials in Denmark, with the notable exception of the Gotlandic stones common in Sweden earlier in the Viking era.

Following that, and probably as a result of the expansion of Christianity, the employment of stone for durable monuments became more commonplace.

Metal

Aside from the fragmentary records of stone and wood, our understanding of the Viking concept of art to date is based mostly on the examination of decorative metalwork ornamentation from a wide range of sources. Several archeological sites have been successful in preserving metal artifacts for future research, and the longevity of precious metals, especially, has allowed us to observe the considerable creative expression and effort put in by the Viking artists and craftsmen.

Jewelry of many designs was worn by both Viking men and women. Married ladies used matching sets of huge brooches to connect their overdresses above the shoulder.

Due to their domed design, modern academics refer to them as “tortoise brooches.” Women’s brooches varied in style and design and women typically tied metal links or beaded strings between the brooches or hung decorations from the brooches’ base. Men typically wore rings on their fingers, necks, and arms and also wore penannular brooches, sometimes with opulent pins to keep their cloaks closed.

Their weapons were frequently elaborately ornamented, especially on objects like sword hilts. The Vikings primarily wore bronze or silver jewelry, which was sometimes gilded, although a few big and extravagant items in solid gold have been discovered, most likely belonging to royalty or important people. Because of the popular practice of creating tombs accompanied by grave items, ornate metalwork is often unearthed from Viking Age graves. The deceased were clothed in their finest jewelry and clothing and were buried with tools, weapons, and household items.

Less common, but no less noteworthy, are discoveries of valuable metal artifacts in the form of treasure hoards, many of which appear to have been hidden for safe-keeping by owners who were subsequently unable to collect their contents, while others may have been placed as gifts to the Viking gods.

Lately, as metal-detecting has grown in popularity, a growing number of isolated, random discoveries of metal artifacts and decorations have created a rapidly developing body of new content for research. Viking coins fall into this group, but they also comprise a distinct category of Viking Age artifact, their Viking design and ornamentation being essentially independent of the evolving forms typical of broader Viking creative activity.

Textiles and Tattoos

Little has survived except stone, wood, and metal. Written accounts let us learn about some of the various materials employed by the Vikings in their crafts. The Vikings, like most civilizations, employed textiles for both clothing and creative expression. We have examples of rich households having tapestries displayed in their houses.

We also have indications that the Vikings tattooed their bodies.

Because skin decomposes quickly, no instances have been discovered; nonetheless, it is conceivable that a well-preserved sample will be discovered eventually. We have evidence from texts outside of Scandinavia by persons who recounted encounters with Norse folk.

In his writings, the famed Islamic traveler Ahmad Ibn Fadlan mentions a group of individuals – often considered to be Volga Vikings – as having dark green or blue “patterns” tattooed from “the neck down to the toes “.

The Styles of Viking Artwork

Traditional Viking art is divided into artistic periods that, although extensively overlapping in design and chronology, may be identified and recognized by fundamental Viking design features as well as recurrent compositions and themes. Naturally, these stylistic stages are most common in Scandinavia; elsewhere in the Viking realm, noticeable influences from exterior cultures are common. Art historians in the British Isles, for instance, find separate, “Insular” interpretations of Scandinavian themes, frequently alongside “pure” Viking ornamentation.

The Oseberg Style

The Oseberg style is the first stage of what has been regarded as Viking artwork. The Oseberg style is named after the discovery of a well-preserved and finely adorned longship in a vast burial site at the Oseberg farm in Vestfold, together with several other elaborately decorated wooden artifacts.

The so-called grabbing beast is a popular character in the Oseberg style. This theme is what clearly separates early Viking artwork from previous forms.

The grabbing beast’s main characteristics are its paws, which hold the borders surrounding it, neighboring monsters, or sections of its own body. The Oseberg Ship, which is now housed at the Viking Ship Museum in Bygdy, was almost 70 feet long and contains the corpses of two women as well as numerous valuable artifacts that were likely taken by thieves before it was discovered.

The Oseberg ship is decorated with a more traditional kind of animal motif interlace that lacks the grabbing beast design.

The Borre Style

The Borre style encompasses a variety of geometric interlace and Norse knotwork patterns as well as zoomorphic motifs that were initially identified in a series of gilt-bronze harness mounts unearthed from a ship tomb at Borre mound cemetery near Borre, and from which the style receives its name.

Borre style was prevalent in Scandinavia during the late ninth to late 10 centuries, according to dendrochronological evidence from sites containing Borre style artifacts.

The “grabbing beast” with a ribbon-shaped body remains a feature of this and previous Viking designs. The visual emphasis of the Borre style, like geometric patterns in this period, arises from the utilization of available space: ribboned animal plaits are tightly intertwined and animals are positioned to produce compact, tight compositions. As a result, any backdrop is conspicuously lacking – a Borre style feature that contrasts sharply with the more open and flowing compositions that predominated in the overlapping Jellinge style.

Borre style is distinguished by a symmetric, “ring-chain” composition consisting of interwoven circles divided by crosswise bars and a lozenge inlay.

Borre ring chains are occasionally capped with an animal head in high relief, as seen on Gokstad and Borre strap fittings. Metalwork ridges are sometimes nicked to simulate the filigree wire used in the greatest examples of Viking workmanship.

The Jellinge Style

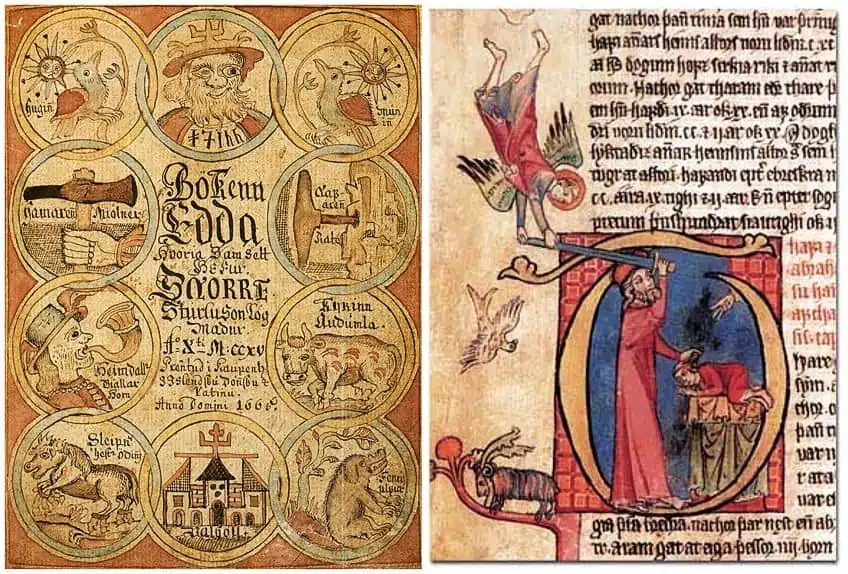

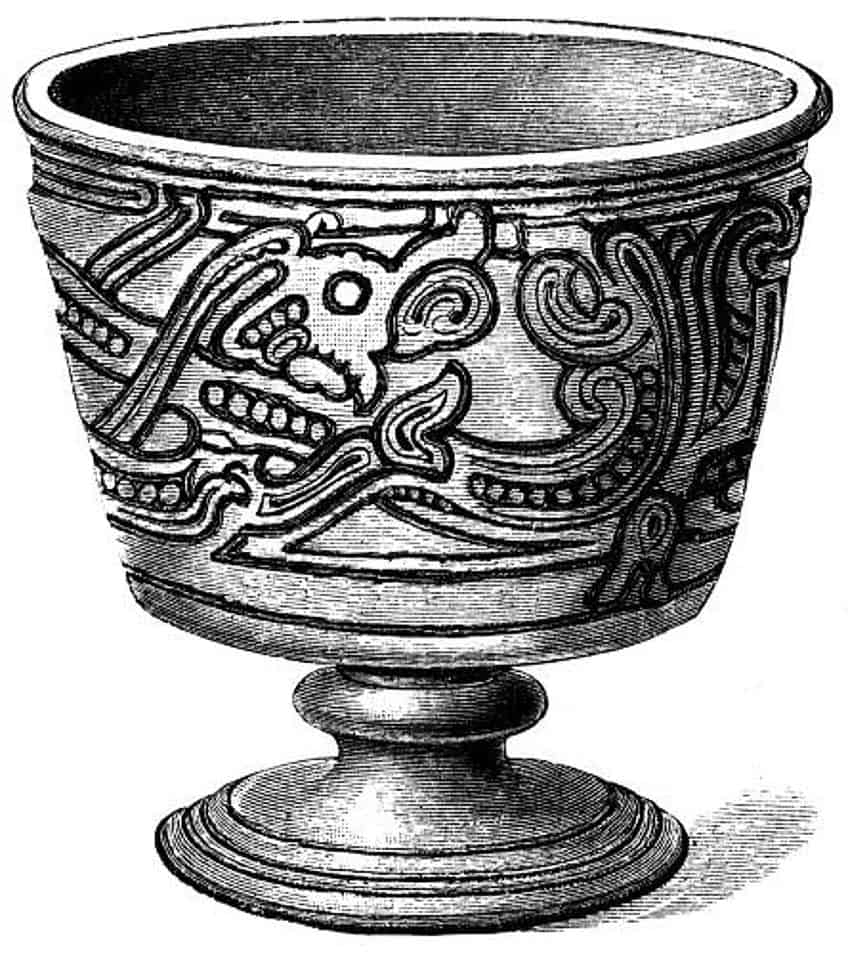

The Jellinge style is a period of Scandinavian animal iconography that flourished in the 10th century. The creatures’ bodies are stylized and frequently band-shaped in this style. It was initially given to a group of artifacts in Jelling, Denmark, including Harald Bluetooth’s huge runestone and Gorn’s cup, but it has since been incorporated into the Mammen style. The style appears on a wide range of items and might share characteristics with prior and succeeding styles, making it difficult to classify as a distinct phase.

The major pattern of this design may be seen around its belly: a series of interlacing animals that form a row of flowing, S-shaped formations.

Single rows of beading cover their body, and their feet look like mittens. Lappets, which resemble ponytails, protrude from their heads, differentiating them from Borre-style animals. This style’s compositions expand outwards, with the backdrops becoming more visible. Human and animal anatomy is simplified, with bodies shown as solid masses outlined by single or double-contoured lines. Spirals symbolize hip joints, while little geometric parts, such as those found on the Jellinge cup, designate wrists and ankles.

While ribbon animals grow more apparent and the grabbing beast retreats, heads have rounder eyes and lips that curve.

The Mammen Style

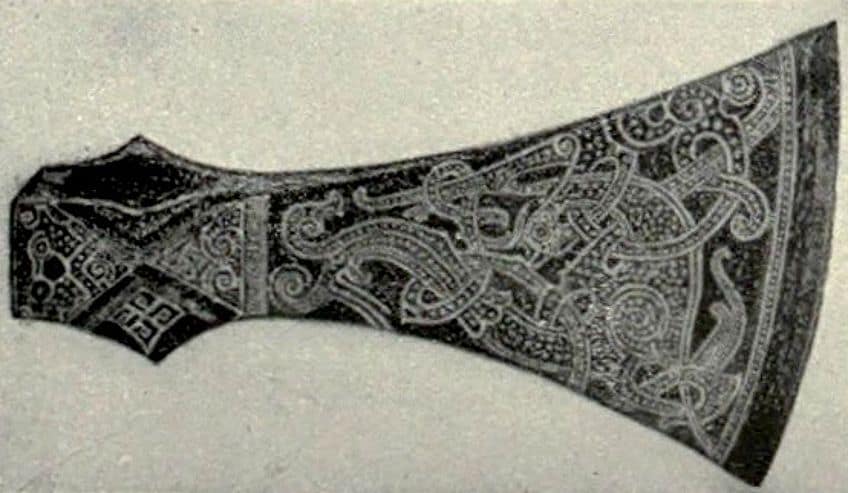

The Mammen style is named after an object discovered during that particular phase, an axe unearthed from an affluent male tomb marked by a mound, the wood utilized in the building of the tomb chamber having been felled in winter 970 AD. The iron axe, richly adorned on both sides with inlaid silver motifs, was most likely a ceremonial display weapon belonging to a man of noble rank, his funeral robes bearing intricate needlework and embellished with fur and silk.

The Mammen axe has a huge bird with a crest on one side. A huge shell spiral marks the hip of the bird, from which its slightly extended wings arise. On the other side, is a sweeping leaf pattern with swirls at the bottom and thin, “pelleted” strands extending and interweaving across the axe towards the narrow end.

The Norsemen valued axes and used them for both household and military reasons, but the carvings on the Mammen axe show that it was a ceremonial item.

A great theme arises in this style: the Great Beast. It may be seen on one side of the Jelling Stone, over a runic inscription referring to his conquering of Norway and the religious transformation of Denmark. The Great Beast is a cross between various creatures, with what appear to be horns or antlers projecting from its head and what looks to be a mane dropping from its long neck. Its clawed feet are segmental, and serpents may twist around its torso in certain renditions, such as the larger Jellinge stone, to create a dynamic interaction between the two themes.

The monster has been viewed as a power symbol. These colossal stones, carved with runic inscriptions, were constructed by King Bluetooth in honor of his departed parents. Bluetooth, as a Christian convert, was instrumental in Denmark’s growing acceptance and embrace of the faith.

He had Christ tied in tendrils that ended in prominent leaf shapes shown on one side of the bigger stone. This runestone is extraordinarily detailed for a runestone, with an inscription encircled by serpentine adornment on its third side. The Bamberg casket from southern Germany, the Cammin casket from Kamen Pomorski, and the León reliquary from Spain, the only known Viking artifact from the Iberian Peninsula, are three exceptionally beautiful examples of the Mammen type that have survived until today. These three examples show how Mammen-style artifacts have been discovered in a variety of locations, demonstrating once again the breadth of Norse visual culture.

The Ringerike Style

The Ringerike style is derived from the Mammen style. It got its name from a series of runestones with plant and animal patterns in Oslo’s Ringerike area. A two-meter-high engraved stone from Oppland is the most widely used type item to characterize the Ringerike style. The majority of the surface of the Vang Stone, aside from a runic commemorative inscription on its right-hand side, is covered with a symmetrical tendril adornment originating from two shell spirals at the bottom: the main strands cross twice to conclude in lobed tendrils. More tendrils emerge from the circles at the crossings, and pear-shaped motifs emerge from the tendril centers on the higher loop.

Despite its axial design, the distribution of the tendrils exhibits a fundamental asymmetry. A big galloping animal depicted with spiral hips appears above the tendril pattern.

When the Vang Stone wildlife designs are compared to the associated living creatures from the Mammen axe-head, the latter appears to lack the axiality found in the Vang Stone, and its vines are far less methodical: the Mammen scroll is curly, whereas the Vang scroll seems to be evenly curved and taut, these features highlighting a critical distinction between Mammen and Ringerike adornment. When contrasting the Vang Stone animals to those seen on the Jelling Stone, the connection between the two types becomes clear.

Birds, lions, band-shaped creatures, and spirals are the most popular Viking designs. Some features, such as different forms of palmettes and crosses that connect two motifs, emerge for the first time in Norse artwork. The majority of the themes are found in Anglo-Saxon, Ottonian, and insular art. The Ringerike style demonstrates the incorporation of European elements into Norse aesthetic standards. Folates and tendrils, for example, have a variety of functions that were influenced by British and French ideas and adapted to suit Norse tastes.

Tendrils stretch forth from animal bodies in bunches of varied thicknesses. This may be observed on various weathervanes that were traditionally gilded, mounted to ship prows, and afterward reinstalled on church roofs. Their borders include friezes of vegetative patterns, and their plates have monsters entwined inside foliates, including the Great Beast and birds. In the Ringerike style, new versions of the Great Beast arise.

The Great Beast may appear alongside other Great Beasts, many snakes, or monsters that we do not always recognize. A carved stone slab discovered in London’s St. Paul’s cemetery, for example, depicts the Great Beast with lengthy tendrils that curve at the far end, producing a tendril-like tongue and horns.

It features spiral hip joints as well. Its body is wrapped with a snake, while a smaller animal wraps around one of its forelimbs. The carved stone slab was found at the bottom of a box tomb. The runic writing on its side indicates that the sculptor was Swedish. As Christianity grows in prominence, burial practices change, and there are fewer grave items in the Ringerike type. Architecture, weaponry, and ivory sculptures become increasingly common, and runestones, albeit less elaborate than the larger stone built at Jelling, become more prevalent.

The Urnes Style

The Urnes style was the final stage of Scandinavian wildlife artwork that was produced in the early 12th century. The Urnes style has been named after the Urnes stave church’s northern gate, although the majority of the artifacts in the period are runestones from Uppland, which is why some researchers choose to refer to it as the Runestone style. The design is distinguished by thin and stylized animals intertwined into tight patterns. The skulls of the creatures are viewed in profile; they have narrow eyes and upwardly coiled extensions on their necks and noses.

This design gained popularity in mainland Scandinavia, possibly as a result of the rise of Christianity. Surviving examples include buildings and runestones, both of which might mix Christian and Pagan symbolism at the same time.

Despite its Swedish beginnings, this style is connected with a stave church in the Norwegian settlement of Urnes. Its relief carvings, which perfectly encapsulate the style’s qualities, have long been the focus of art-historical study. Their rhythmic works feature graceful swooping, symmetric, and interlaced motifs, as well as a more apparent background.

Although spiral hip joints are still used, the proportions of animals’ bodies bend and expand in a way that distinguishes them from prior forms. The eyes have expanded to nearly fill the skulls, and the lower jaws have hook-like extensions. The Great Beast’s feet, which are positioned close to the entryway, finish in wisps that lie amid delicate vegetative patterns. Although the structure is Christian in purpose, the ornamental features are pre-Christian.

This style’s characteristics were carried with the Norsemen when they traveled, traded, and established in new areas.

Urnes-styled artifacts may be found throughout the Baltic, and specimens like the Pitney Brooch show a regional adaption in England. The Norse re-occupation of Dublin fuelled artistic appreciation of the Urnes style in Ireland, with stone and metal artifacts displaying its characteristics. When gazing at the gold filigree ornamenting St. Patrick’s bell shrine, for instance, precisely-crafted designs show a focus on geometrical and rhythmic compositions. Nevertheless, the style’s appeal there arrived just as it was waning in Scandinavia.

The introduction of Romanesque artwork to the North severely limited local aesthetic design. Christianity necessitated Christian architecture, and Scandinavians relied on precedents from elsewhere: the countries are filled with hundreds of tiny, stone churches – and a few huge ones – inspired by examples from England, the Rhineland, and Lombardy.

Nevertheless, local forms were still used for wood carving in the 12th and 13th centuries, and the extraordinary architecture and sculpture of Norwegian churches demonstrate the endurance of warring dragon themes long into the Christian eras.

Contemporary Viking Art

The Viking art heritage continues to this day. Contemporary examples include products for sale that are replicas, many of which are well-crafted and historically correct. Others are constructed in these styles, while some just replicate artifacts. Because of the ongoing attraction of the genres, elaborate wood carvings, runestones, and exquisite metalwork are all prominent. Replica swords and shields are very popular. These allow for historical performances and displays during the numerous Viking festivals held across Scandinavia.

There are also individuals who make replica coins and jewelry, offering an accurate impression of Viking culture as it would have been.

Viking concept art is frequently linked to one of the numerous TV series on the air these days, most famously the “Vikings” series on the History Channel. The majority of the characters in the program are based on real people, and fans construct renditions of their favorite characters in a range of realistic settings.

Viking art, as one might assume from a race of violent outdoor warriors, is more practical and symbolic than introspective or expressive. Because Vikings were frequently on the move, much Norse art consisted of portable artworks such as painted body armor, drinking horns, pagan iconography, paddles, and a variety of everyday goods. Nonetheless, their wood carving and sculpting demonstrate considerable imagination and ability, and Viking craftsmen have left a rich heritage of elaborate animal adornment. Their metalwork was likewise of excellent quality, and it was both inspired and was also inspired by Celtic metalwork art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Celtic and Norse Knotwork?

Celtic knotwork, also known as Icovellavna, has an extremely rigorous, mathematical framework. Celtic knots are well-defined and usually consist of a single solid continuous line that wraps around and through itself. Lace, spirals, step, and key patterns are other common Celtic motifs. The style is more abstract and the line is thicker, whereas Norse knotwork is more likely to portray animals, people, and things. Both countries’ knotwork is quite similar, and because of its rebirth in tattoo shops and jewelry stores throughout the world, a lot of modern-day artwork incorporates inspirations from both cultures.

Why Is Most Viking Art Found Outside of Scandinavia?

Scandinavia’s population grew, and given the harsh environment, it only took a few more mouths to feed for tiny pastures to become overcrowded. Simultaneously, the Viking ocean-going ship, the Knorr, had acquired a high level of technological advancement, allowing men to travel to the Mediterranean and over the Atlantic. Also, the disintegration of Charlemagne’s empire and civil turmoil in the British Isles created a power vacuum, which the Vikings quickly filled. Although they seldom missed a chance to invade and plunder a town or monastery full of treasures, the Vikings occasionally traveled for benign reasons.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Viking Art – The Exciting World of Viking Culture and Norse Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 7, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/viking-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 7 October). Viking Art – The Exciting World of Viking Culture and Norse Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/viking-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Viking Art – The Exciting World of Viking Culture and Norse Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 7, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/viking-art/.