What Is Mezzotint? – Printing With Subtle Shadow Gradations

What is a mezzotint and what does the mezzotint process involve? In mezzotint art, the image is formed using subtle gradations of shade and light instead of lines. This technique was developed by mezzotint artists in the 17th century. To learn more about the history of mezzotint prints, read further below!

What Is a Mezzotint?

During the first half of the 17th century, the mezzotint process was developed in Amsterdam, which at the time, was a significant center of printmaking. But, which mezzotint artists were responsible for developing this process? Let us learn more about the history of mezzotint art before we break down the mezzotint process.

The History of Mezzotint Art

Two foreign artists working in Amsterdam at the time, Ludwig von Siegen from Germany and Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the exiled Bohemian royal, developed the technique almost simultaneously yet independently. When both men’s interests turned to other endeavors, Prince Rupert’s former assistant, a painter from France called Wallerant Vaillant, established himself as the first professional mezzotint engraver. His considerably large output fueled the medium’s rising appeal; mezzotint prints were created and exhibited throughout Europe within 20 years of the mezzotint process’s development.

In London, mezzotint prints gained a particularly receptive audience.

The Emergence of Mezzotint Artists

Following the British monarchy’s restoration in 1660, several Dutch mezzotint engravers arrived, including Jan van Somer, Abraham Blooteling, Jacob Gole, Pieter Schenk, and Gerard Valck. They passed on their knowledge to authors who detailed the mezzotint process in books and instructed native-born artists on the technique. England was home to several talented mezzotint engravers by 1700, including Isaac Beckett, Robert Robinson, William Sherwin, Francis Place, Bernard Lens II, and John Smith. Only 50 years had elapsed before London replaced Amsterdam as the center of mezzotint creation.

There, in the latter half of the 18th century, the technique known as la manière anglaise would reach its peak. While some London-born printmakers rose to fame, such as Thomas Watson and Richard Earlom, quite a few of the talent was from abroad. James McArdell, Thomas Frye, Edward Fisher, Richard Houston, and John Dixon were from Dublin. George-François Blondel was from Paris and Johann Gottfried was from Vienna. John Raphael Smith, William Pether, and Valentine Green were from British towns.

International Growth

Other British mezzotint engravers, such as Charles Howard Hodges and James Walker, took the mezzotint process abroad to avoid the rivalry of this growing saturated and competitive field. However, the mezzotint artists did not prosper outside of the United Kingdom. Jacques-Fabien Gautier-Dagoty created a four-plate color printing mezzotint process in Paris, which was carried on by his sons, but it was costly and failed to survive the French Revolution era.

Ignaz Unterberger, an engraver from Austria, created stunning mezzotints with distinctive ground textures in Vienna.

Johann Jacobé and Johann Gottfried Haid, both of whom spent time in London, created outstanding mezzotint prints and taught the technique to many talented pupils. Mezzotints were produced by a few artists in colonial America, including Edward Savage, Peter Pelham, and Charles Willson Peale, although none did so as their main source of income. It has been employed sparingly since the mid-19th century, as lithography and other processes achieved equivalent results with greater ease. Sir Frank Short, together with Peter Ilsted in Denmark, were key figures in the rebirth of mezzotint art in the U.K.

Modern Mezzotint Art

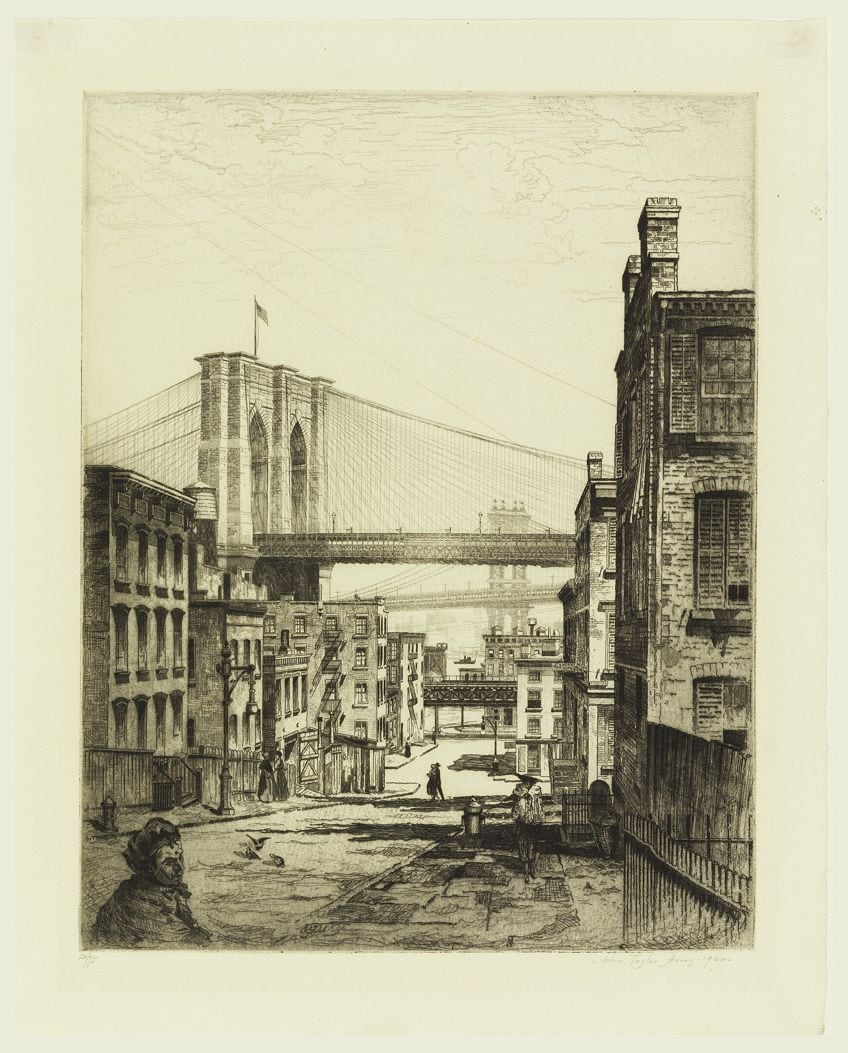

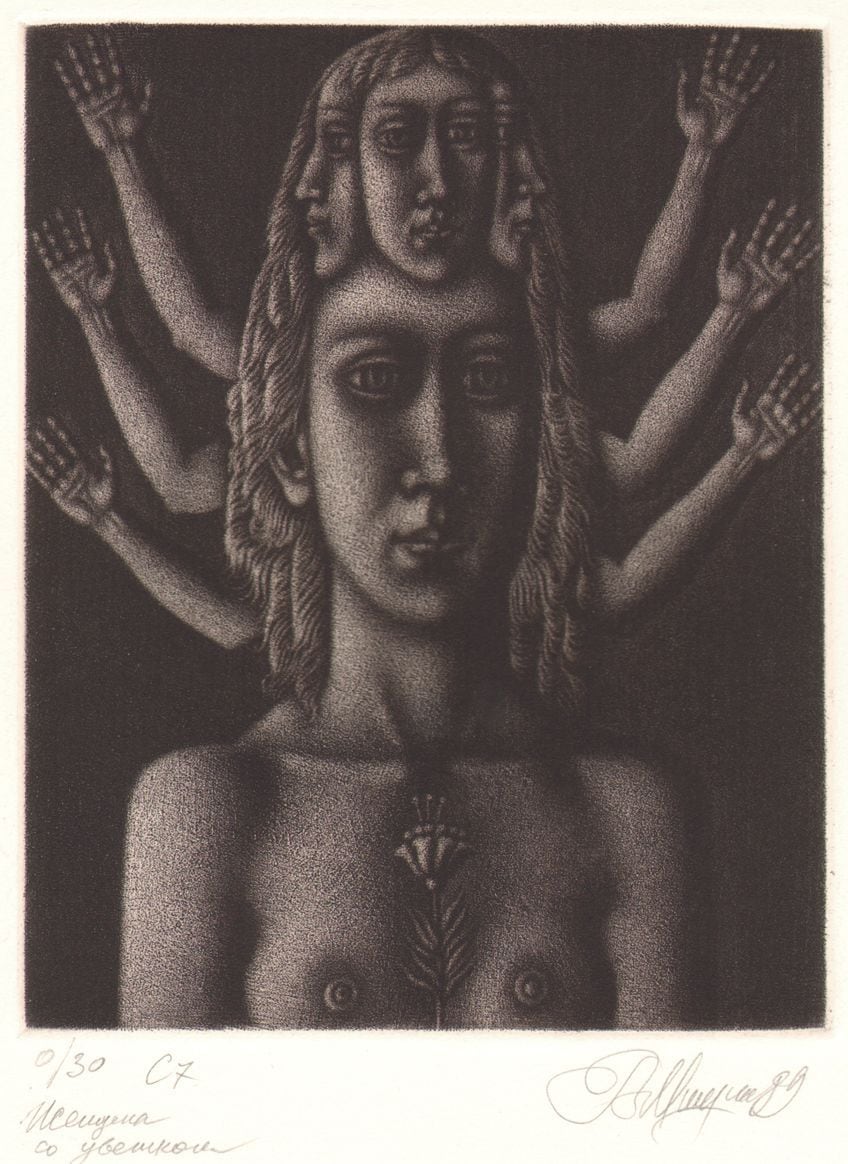

To manufacture prints, photogravure, and lithography grew more popular than mezzotint printing around the turn of the 20th century. However, some people continued to use the method, particularly those who appreciated how it allowed them to create mezzotint art prints with a lot of detail and rich colors. Mezzotint witnessed a rebirth of popularity among printmakers and artists in the 1960s and 1970s, notably in the United States. Artists such as Leonard Baskin, Robert Kipniss, and John Taylor Arms continued exploring the technique’s potential, enabling mezzotint’s return to the printmaking process in the modern art world. Mezzotint is still used by printmakers and artists in the 21st century, however, it is a specialized technique. Many modern painters and printmakers appreciate this approach because it produces beautifully toned, detailed images with a distinct tactile quality.

The Function of Mezzotint Art

In comparison to etching, which has a long history of artist-printmakers, only a few artists used mezzotint prints to express themselves creatively. Rather, from its inception, the mezzotint has mostly functioned as a way for converting oil paintings to printed form. Its novel use of tone instead of line, and outstanding ability to convey texture, made it ideal for this purpose. Furthermore, the velvety black and deep brown tones corresponded to a prevalent 17th-century preference for intense chiaroscuro in oil paintings, a style that also remained popular in 18th-century British art. While the first mezzotints were reproductions of the works of previous masters, contemporary artists quickly adopted this technique for promoting their own artwork.

Because a mezzotint can be produced at a lower cost and speed than a line engraving, it became an increasingly common technique for distributing timely illustrations.

Leading British subject and portrait painters collaborated extensively with mezzotint engravers in the latter half of the 18th century to create competent copies of their paintings, which were often displayed alongside their painted versions at London’s annual art shows. These mezzotint prints sometimes became more valuable than the creators intended: in order to fulfill the rising demand, less credible publishers did not hesitate to make their own copies of successful works. Mezzotints were readily available, supplied in a variety of sizes designed to fit standard-sized frames, and were priced to match any budget. Collectors put together portfolios or books of mezzotint prints depicting notable individuals of the day, and they exhibited mezzotints making mezzotint replications of genre, historical, or still-life themes on their walls.

Mezzotint drawings were copied onto pieces of glass, which were then colored in oils or watercolors to imitate paintings. By the mid-1770s, when gilders and framers gradually took over the furniture prints industry, mezzotint art had begun to dip in popularity due to another printmaking method: stipple engraving. The stipple method, invented in France in the 1760s, employs dots to generate tone, and its plates are able to endure more prolonged print runs than mezzotint plates. Faced with this rivalry, mezzotint artists and publishers took a different approach. Some explored color printing processes.

Others broadened their subject matter and released a sumptuous series of mezzotints aimed at rich collectors.

The Mezzotint Process

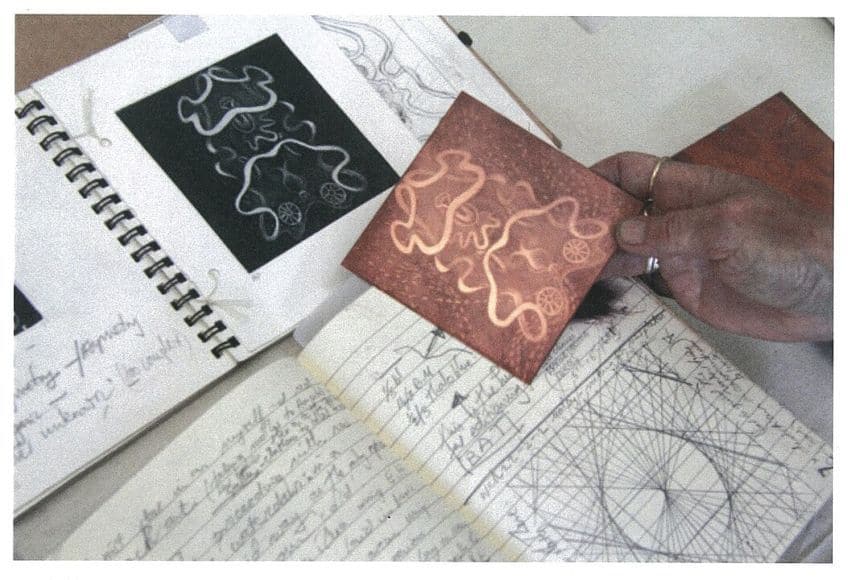

Now that we have covered the history and function of mezzotint art, we can turn to the mezzotint process itself. There is the dark-to-light method and the light-to-dark method. Let’s learn more about the difference between these two methods in the chapter below.

The Light to Dark Mezzotint Process

Ludwig von Siegen created the first mezzotint prints using the light-to-dark mezzotint process. The metal plate was tooled to produce indentations, and areas of the artwork that needed to remain light in tone were smoothed. This approach was known as the “Additive method” because it involved making indentations to the metal plate for parts of the print that were to be deeper in tone. This technique allowed the artwork to be produced directly by roughening a blank plate specifically where the darker sections of the image were to go.

Mid-tones between white and black can be made by adjusting the degree of smoothness.

The Dark to Light Mezzotint Process

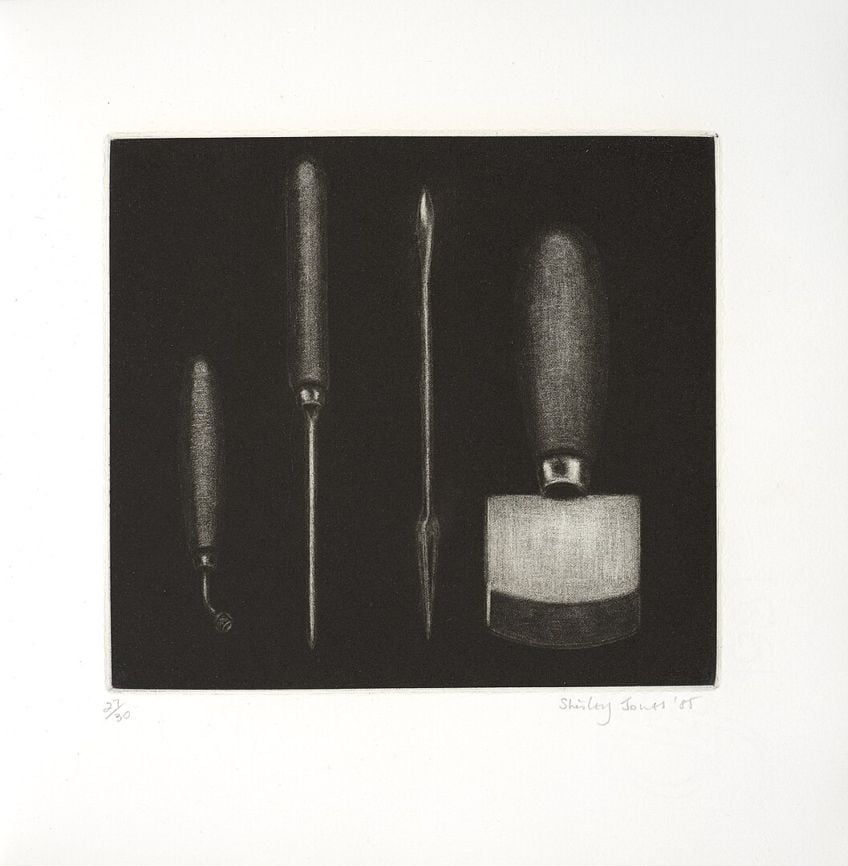

This mezzotint process became the most popular. The whole surface of a metal plate, often copper, is roughened equally, either mechanically, or manually using a rocker. If the plate was printed at this stage, it would be completely black. The illustration is then produced by selectively burnishing regions of the metal plate’s surface with metal tools; the areas that have been smoothed are going to appear lighter than those that have not been polished by the burnishing tool. Areas that have been entirely sanded flat will not contain any ink and will print “white”, or the color of the paper when it does not have any ink on it. Prince Rupert of the Rhine originally pioneered this approach.

The all-over roughening requires little expertise and is often performed by an apprentice. The technique had two major advantages: it was easy to learn and much faster than traditional engraving, and it produced a wide spectrum of tones. Mezzotint prints could be made quickly in order to react or represent events or individuals in the news, and bigger print sizes were reasonably simple to manufacture. This was critical for what was commonly referred to at the time as the furniture print, which was a mezzotint print large enough and with enough dramatic tonal contrasts to stand on its own framed and displayed on a room’s wall. This proved to be very popular as mezzotint prints were far cheaper to produce than paintings.

Color Mezzotint Prints

Jacob Christoph Le Blon developed the three and four-color mezzotint printing process by employing a different metal plate for each hue while applying the dark-to-light method. Le Blon’s color printing process used the RYB color model approach, which combined yellow, red, and blue to generate a wider spectrum of color tones. Later in the century, Jacques-Fabien Gautier-Dagoty, a pupil of Le Blon, made use of a similar approach in France; his output included anatomical images for medical texts.

Other black-and-white prints were hand-colored in watercolor, which came in handy as the plate began to fade over time.

Printing Mezzotint Art

Printing the final plate is the same for both methods and uses the standard technique for an intaglio plate; the entire surface is inked, and the ink is subsequently wiped off the surface, leaving ink only in the indentations of the remaining rough sections beneath the plate’s original surface. The metal plate is then fed into a printing press alongside a sheet of paper, and the entire process is then repeated. Because the pits in the plate are shallow, only a few high-quality impressions are able to be produced before the tone begins to deteriorate as the press pressure smooths them out. Only 100 to 200 proper impressions can be achieved before the quality of the print begins to deteriorate, but plates were often “refreshed” by additional rocker work. However, whether done by the artist’s apprentice or a printer, the plate was typically refreshed to a lesser grade.

Detailed Techniques

Plates are able to be mechanically roughened by rubbing fine metal filings over the surface using a piece of glass. The finer the filings, the finer the grain of the surface. Since at least the 17th century, special roughening tools known as “rockers” have been in use. When rocked continuously from side to side at the right angle, the tool will continue to move forward, leaving burrs on the copper’s surface. The plate is then spun a certain number of degrees, and then rocked in another cycle.

This process is then repeated until the plate is equally roughened and prints a totally solid black tone.

Renowned Mezzotint Artworks

Printers can produce an incredible degree of realism and detail with mezzotint art. Mezzotint works exhibit an exceptional degree of artistry, from complicated line work to nuanced tone changes. Every piece tells a unique tale and reflects the artist’s character and style.

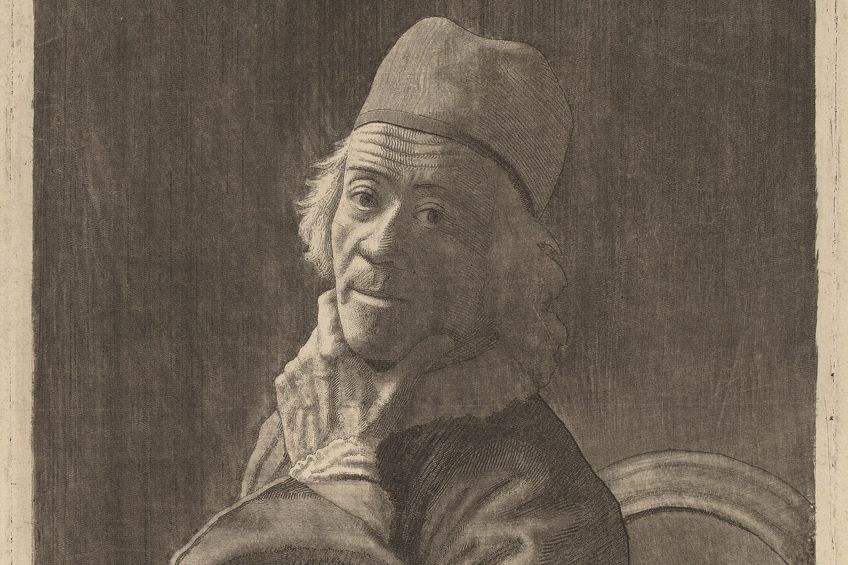

Self-Portrait (1785) by Jean-Étienne Liotard

| Artist Name | Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702 – 1789) |

| Date Completed | 1785 |

| Medium | Engraving over mezzotint |

| Dimensions (cm) | 48 x 40 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

This is a mezzotint paper print by Jean-Étienne Liotard, a Swiss artist from Switzerland. The piece depicts Liotard seated in front of a simple background, dressed in Ottoman clothing and wearing a turban. It was most likely designed to depict his physical appearance, talent, and personality. The artwork is especially famous for Liotard’s unique clothes, which reflect his travels and curiosity in different cultures.

It is presently housed in Switzerland, Geneva, at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire.

Dewdrop (1948) by Maurits Cornelis Escher

| Artist Name | Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898 – 1972) |

| Date Completed | 1948 |

| Medium | Mezzotint |

| Dimensions (cm) | 17 x 24 |

| Current Location | North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina |

C. Escher used the mezzotint process just eight times throughout his career, one of which was Dewdrop. Many viewers like Escher’s portrayal of the light touching the edge of the leaf in this famous mezzotint artwork. Escher once stated that the thing he most sought was a sense of awe, and he attempted to evoke it in his viewer’s minds. Almost nowhere else is that feeling of amazement more vividly represented than in Escher’s mezzotints. In this mezzotint artwork, he perfectly captured the look of a dewdrop resting in a leaf.

Mezzotint was especially well-known for creating fine art and portrait prints in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was one of the few processes available at the time that was capable of producing a high tonal variety, allowing for a more faithful portrayal of the original piece of art. Making a mezzotint print takes time, and the process of printing wears down the plates after a limited number of impressions. The resulting images, however, are incredibly detailed and have a velvety and rich feel that is still highly valued today. This technique can be utilized by artists to produce an appealing and detailed print, which is typically used to reproduce paintings and sketches. Printers utilized mezzotint prints to create book illustrations, as well as maps and building drawings in the 18th century.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is There a Difference Between a Mezzotint Print and an Etching?

They are both printing processes used for producing artwork on metal plates, but the approach and end result of either are not the same. Etching produces an image by adding a protective covering to a metal plate, such as varnish or wax, and then tracing a line through the layer and into the plate with a sharp instrument. After that, the plate is placed in an acid bath, which dissolves the exposed metal, resulting in lines or patches of different depths. To create the final print, the plate is then inked and pushed onto paper. The finished image contains fine lines that make it look more like a sketch. A mezzotint image is created by scraping and burning a plate coated in tiny metal burrs. When the plate is inked and cleaned, the scraped and buffed parts of the plate are unable to hold ink, which produces a lighter section of the print.

What Characterizes a Mezzotint Print?

If given a piece of artwork to examine, an art trader will be looking for the distinctive fine, crosshatched lines in varying hues of gray to identify a mezzotint print. They are the result of the scrapes of a toothed tool. These outlines are visible on the print’s borders. The mezzotint print can easily be distinguished by plate marks and raised ink levels typical of an intaglio press. With early mezzotint plates, extreme wear was expected. This means that reprints were substantially lighter than the initial ones printed.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “What Is Mezzotint? – Printing With Subtle Shadow Gradations.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 14, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/what-is-mezzotint/

Anthony, J. (2023, 14 November). What Is Mezzotint? – Printing With Subtle Shadow Gradations. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/what-is-mezzotint/

Anthony, Jordan. “What Is Mezzotint? – Printing With Subtle Shadow Gradations.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 14, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/what-is-mezzotint/.

Nice description of the most beautiful and most difficult etching technique, but little attention to the contemporary artists.

Ronny