Zdzisław Beksiński – Works of the Dystopian Surrealism Artist

Polish artist Zdzisław Beksiński was a photographer, sculptor, and painter. His alchemic process mixed emotions, free associations, and external factors to create a window into his imagination. Beksiński is widely regarded as the godfather of creepy sketches and twisted art which defies categorization. Beksiński’s paintings are frightful, macabre, and dystopian nightmares on canvas.

Into the Abyss with Zdzisław Beksiński

| Date of Birth | 24 February 1929 |

| Date of Death | 21 February 2005 |

| Place of Birth | Sanok, Poland |

| Associated Art Movements | Surrealism, Magic Realism |

| Genre / Style | Baroque, Gothic |

| Mediums Used | Painting, Photography, Sculpture |

| Dominant Themes | War, doomsday, devastation, death, desolation, emaciation, spirituality, eroticism, religion, architecture |

Throughout his 50-year career, Zdzisław Beksiński‘s paintings went through a variety of styles. Much of his work echoed the horrors of World War II, but his dark aesthetic has become particularly popular in the internet age.

Beksiński brought global attention to Polish art and he is arguably the greatest Polish artist to date.

A Product of War

Polish artist Zdzisław Beksiński was born in Southern Poland in the town of Sanok in 1929. When Beksiński Zdzisław was ten, World War II began and the Nazis invaded Poland. In 1940, the Zaslav concentration camp was erected on the outskirts of Sanok and would be in operation for the next three years.

Although Beksiński was not Jewish, Sanok had one of the largest percentages of Jewish people in the country, with over 30% of its people being Jewish.

Nazi Germany was conquered after the counter-invasion from the Soviets. A new superpower had been established and during the Soviet occupation of Poland, the war went cold. New weapons of mass destruction were introduced onto the world stage and nuclear war had the potential to put an end to all of human existence.

Zdzisław Beksiński’s dreams had always been grim. As a child, one night he had dreamed about a fountain pen that he had coveted but couldn’t afford. In his dream, he spotted one on the grass, and shortly after, he found another one. Eventually, he had an armful of pens and felt ecstatic. But then he woke up empty-handed. He was overcome by a feeling of nothingness. He acknowledged that that feeling of nothingness stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Though he never received a formal art education, he began to draw from an early age. In 1947, he went to study architecture at Kraków Polytechnic, graduating in 1952 with an MSc. At Kraków Polytechnic, he was able to develop his draughtsmanship and learn about the history and symbolism of architecture. In 1955, he moved back to Sanok and worked in a construction stand, designing busses for a company called Autosan.

Impure Photography

In the aftermath of the war, Beksiński began to experiment with sculpture and photography. He incorporated objects he had found at the construction site where he worked into his images. He enjoyed it so much he began doing photography part-time for the next three years.

By 1957, Zdzisław Beksiński’s photography began to gain recognition for its surreal depiction of the Polish artist as well as others.

The dominant movement of photography around that time was Pure Photography, pioneered by photographers like Edward Weston, Paul Strand, and Ansel Adams. In this school of photography, the objective was to create as sharp an image as possible, capturing every true and natural texture of the subject. This style came about in response to Pictorialism, the leading movement in photography of the early 1900s. Pictorialists aimed for a more painterly image, depicting their subjects in a Romantic and obscure way.

When Beksiński unveiled his photograph Sadist’s Corset (1957), he faced immediate backlash because of its posed, stylistic characteristics. It did not subscribe to the conventions of the nude. The figure faces away from the camera, positioned in a rigid, asexual manner, and segments the subject are sliced up. He had used the obscured figure in other images, where objects like mirrors disrupted the natural symmetry of the body. The chair in the foreground of Sadist’s Corset is out of focus, making the image disorienting.

The critic Alfred Ligocki publicly denounced the photograph because of the photographer’s intervention on the subject. He claimed that Sadist’s Corset failed to represent the subject truthfully, deeming Beksiński’s work as anti-photography. Beksiński rebutted this in an article called The Crisis Of Photography And The Perspective To Overcome It. In it, he claimed that Pure Photography left no room for creativity.

By the early 1960s, even though he had become a renowned photographer, he abandoned the medium of donating his photographs to the Historical Museum of Sonak. His experiments with photomontage made him realize that the easiest way to achieve his intention was through a paintbrush.

The Fantastic Period

At this point, he dedicated all his time to painting. From the start of the 1960s until the 1980s, Beksiński produced what has come to be known as his Fantastic series. In 1964, when he exhibited some of these paintings, they were all sold. It was in the Fantastic period that Zdzisław Beksiński made his most famous surreal horror art.

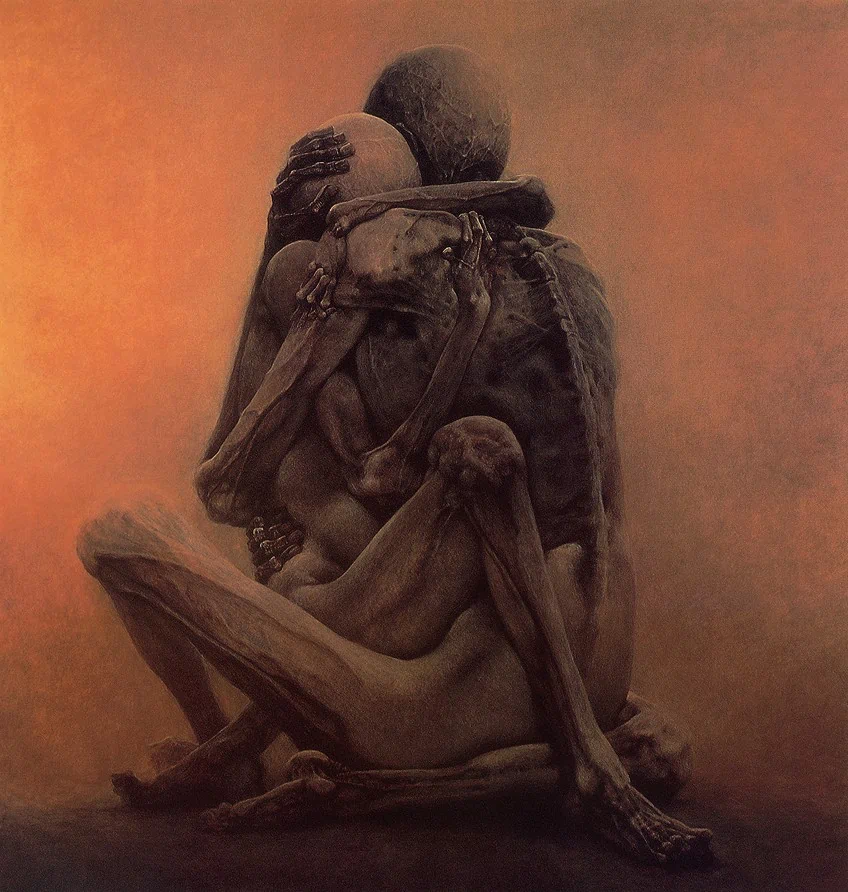

His surreal horror art was infused with hopelessness and despair, which resembled the aftermath of some unearthly disaster that had left absolute annihilation.

Aesthetic and Technique

One of the most intriguing aspects of Beksiński’s painting is that it is virtually transparent. Most artists convey emotion through brush strokes, or what has been called the touch. Often, the surface of the painting reflects the artist’s emotional state. That is not the case with the creepy sketches of this Polish artist. Beksiński had no use for spontaneity. He was more interested in craftsmanship and technique. His images were smooth and controlled.

He believed that the longer he took to finish his creepy sketches, the more likely he was to achieve that sense of dystopian surrealism. In his opinion, rough brushstrokes would be disingenuous and unfinished.

His interest in technique reflected his psyche. When he painted something he was unhappy with, he would modify it 50 times. Something as minute as a finger would occupy his attention, obsessing about its size, its direction, or its tone. One hand was built and repeatedly rebuilt so that it went through many transitions. In the end, instead of a hand, it had become a dog’s head, for instance. This indecision constituted his special painting technique, with layers underneath penetrating through the newer layers.

Even though they were not immediately apparent, these layers of the painting consisted of a cacophony of colors, enriching the surface and giving the impression of greater diversity. The most popular Beksiński art was painted with semitone or earthy tones because he felt a painting that presented less obvious and unintrusive color was more interesting. In his opinion, these “dirty” colors produced a richer mix and contained more range than pure red cadmium, for example.

Many think that Zdzisław Beksiński’s paintings in earlier years had more light and color, while his later works have more toned down colors. Others think that he turned towards the light in later works or at least that he found a new understanding of light.

It is true that Beksiński largely restricted his palette to red and brown, in addition to black and a small number of other colors that held meaning for him. Green, for instance, is a positive color, representing life and the living, so it had no place in Beksiński’s world.

In any case, he felt most people approached tone and color with naivety. For instance, when he used cadmium red or Prussian blue, most viewers just saw red and blue. They did not understand daylight coming through a window as a means of bringing out more tones. They just saw light and dark. Thus, when he was asked about some of the Beksiński paintings being less bright or less colorful, he did not take it to heart. He observed that an advanced spectator could interpret color in a less obvious way.

Interpretation

All of Beksiński’s creepy sketches remain untitled and he was obscure about his artistic intentions. He said: “If I had something to say, I would write it down or say. I don’t need painting for that.” He was insistent about denying meaning altogether. He thought that titling his art would create a misconstrued interpretation of the work.

Because he refused to name his surreal horror art, it was left open for interpretation. There are endless theories about what it all might have meant, but Beksiński would often vehemently contradict and even mock those who attempted to decode his work. The only certainty we have about the artist’s intention is that he wanted it to have no frame of reference other than its aesthetic features.

When he painted a clock face, showing 10 or two and so forth, or a bird on someone’s shoulder, or a gate with bent bars, he never concerned himself with why he had done so. He understood that it was spontaneous, like a dream. Beksiński paintings produced basic associations between various elements that collided with each other, inventing apparent content.

Viewers insisted on combining the elements of Beksinski paintings, pulling them into Surrealism and symbolism. They wanted anecdotes or significance to certain symbols such as a cross, a church, or a tree. Beksiński despised symbolic interpretation, so he refused. He admitted that he shared the Surrealists’ oneiric artistic process but maintained that art should be read-only aesthetically. In a 2002 interview, he said that in his opinion, all interpretation of his art was “imposed by others”.

He did not blame interpreters of his work for wanting simple answers for what his work meant, but he felt that he did not need to personally define his art. For him, it did not have to mean anything. “Meaning is meaningless to me,” he said. “I do not care for symbolism and I paint what I paint without meditating on a story.”

If Beksiński’s art has to be about something, that would be the mood or atmosphere. Vision and feeling were important to the artist who wanted to make sublime, moody, atmospheric art that required focus and silence. He preferred the musical interpretation of his art, aiming to haunt and draw the viewer in. Like a wonderful landscape or simple song, he wanted his paintings to be admired without being asked what they meant.

Inner Landscapes

This nightmare artist was caught in the constant collision of conflicting ideas about art and life. He had said: “All opinions that I allegedly painted dreams come from journalists. In my life, maybe I’ve tried to paint one dream. A fragment from a dream in my early youth. But I never use dreams.” He also said, “I wish to paint in such a manner as if I were photographing dreams.” Of course, these two statements are contradictory and raise even more questions about his intent.

He was at least consistent about his paintings standing for some sort of inner landscape or some sort of self-portrait. These visions had to represent his psychic structure because even he was astonished by what was revealed on the canvas. He said the best images were the ones that were shocking even to himself.

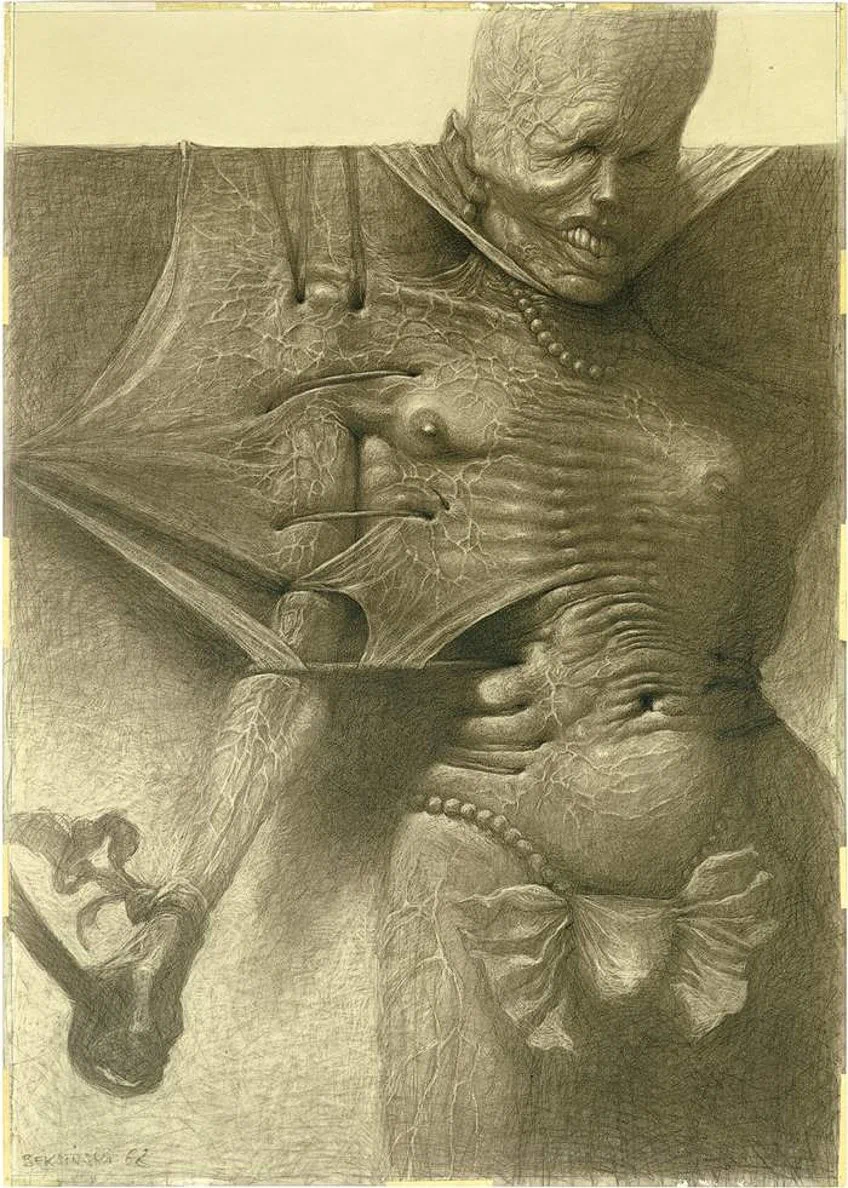

Bodies

The figure is the subject of almost all Beksiński surreal horror art. The most common feature is that they are always emaciated. Beksiński’s depiction of thin bodies is evocative of wartimes. His bodies are never normal and almost always blend into something else, obscuring and stretching their original form. Some bodies morph into new creatures. Faces shift in all directions, blooming into nature until they hardly read as faces at all.

One of his most famous paintings, Untitled (1973), depicts a faceless blind quadruped, pathetically scurrying away from an infernal city. Many Beksiński paintings show decimated cities and weirdly deformed humanoids. In this painting, it seems the figure is looking for something with its right hand or guiding its path, as it cannot see. This could be a metaphor for the modern man.

Each figure represents a parody of life. In other images, figures are segmented into pieces, buildings are made up of bodies, and Notre Dame is made of human bones. Posed in believable ways, which somehow seem entirely unnatural at the same time, there is always discomfort. One of his lesser-known works is a series of sadistic erotic drawings of figures in twisted contortions.

The body is often tied to the concept of crowds, and here, Beksiński must be critiquing crowd mentality. Large groups appear vacant and hopeless.

Religion

The 1970s introduced the latter part of Beksiński’s career, characterized by his focus on huge structures and monuments. The famous Beksiński cross became a prominent feature in many of his paintings. The Beksiński cross is a simple cross with the upper part omitted so that it looks like a “T”. The prominence of this shape shows that it had a significance for him, perhaps a critique of the twisted nature of Christianity.

Beksiński’s surreal horror art featured other religious structures like crucifixes, churches, cathedrals, and Jewish cemeteries. Despite his aversion to meaning, he was not against religious interpretations of his art, and he did mention that Freud believed the church symbolized female genitalia. For that reason, we could deduce that he might have had more sexual motivation than a religious one.

Speculations have been made about Beksiński’s religious beliefs, but he decisively said: “Others consist of beliefs, I consist of doubts.” Beksiński was raised as a Catholic, though his family never imposed it on him. He denounced Catholicism early on without converting to any other religion. He once identified as a “skeptical rationalist intellectual” but was soon recalled by God or eternity, at which point he adopted a personal form of religion not too strictly defined.

His paintings helped him find a language to connect with this spiritual being.

He understood the comfort of seeing the human race as someone’s creation rather than a by-product of evolution. But Beksiński found it hard to relate to the religious understanding of God as someone who created him and needed to be worshipped. He found this paradoxical. Anyone could create something, but these creations are not obligated to appreciate their maker. Take a painting, for example. A painter cannot expect the painting to thank him for being made. It is the painter who must relate to his creation.

War and Death

Beksiński made it extremely hard not to find symbolism in his work, especially when it pertained to war and death. In one of his paintings, a red creature hides behind a building reminiscent of Greco-Roman architecture, which seems like an obvious reference to Nazi leadership. In other words, numbers are tattooed into human figures, and in one work a torso turns into a chair. Once again, it is impossible not to think of the victims of the Germans who were tattooed and sometimes manufactured into household objects like lampshades or soap.

The color blue also has significantly dark implications in his scenes. Beksiński used Prussian blue, so named after Prussic acid, a key component of the paint. Another term for Prussic acid is hydrogen cyanide.

The pigment itself is not toxic, but another product made from hydrogen cyanide is the pesticide Zyclon B, which had been used by the Germans during World War II in their gas chambers and was lethal. After frequent use, the poison would leave a blue residue on the walls of the gas chambers.

In one of Beksiński’s paintings, a figure who looks like the grim reaper wears a cloak of Prussian blue. The figure looks on at a train of carts marked with religious symbols carrying tightly packed emaciated figures away. In Untitled (1974), the same grim reaper hovers over a baby in a cradle while a living male figure is devoured by birds in the background.

Though he admitted to a fear of death, he did not wish for his art to be read as fearful. The nightmare artist had never been able to rid himself of that elementary feeling of nothingness, but he recognized the contradictions.

There had to be some meaning for him, otherwise, there would be no point to his art practice. If a nuclear holocaust had occurred and he was the last surviving human on earth and found some paints and an easel, he would see no reason to paint. He needed an audience and that concept within itself had meaning.

A Gruesome Ending

In 1998, Beksiński’s wife Zofia died due to cancer and in 1999, on Christmas Eve, his son Tomaz committed suicide. This was a difficult time for the artist. Tomaz Beksiński had been a popular radio presenter and music journalist. Not long before his death, Tomaz had written an article about a modern culture where he had practically revealed his intention to kill himself. Years before, Tomaz had tried unsuccessfully to take an overdose of sleeping pills. This time it had worked, and it was Beksiński who found his son’s corpse.

As these tragic events happened relatively late in his life, they had no major impact on his practice. Beksiński’s preoccupation with death was already fully established at that point. For the remainder of his life, he lived in relative seclusion in his small one-room apartment, where most of his final creepy sketches were made.

On the 21st of February 2005, Beksiński had a minor dispute with his housekeeper’s 19-year-old son who wanted to borrow the equivalent of roughly $100. When the artist refused, the situation escalated and the teenager stabbed Beksiński 17 times, leaving him dead. His lifeless body was found in his apartment the next day. How strange that this nightmare artist should meet such a surreal and nightmarish demise.

Whatever Zdzisław Beksiński’s art may mean, his creepy sketches which depict a dystopian surrealism seem relevant beyond his time. Zdzisław Beksiński’s photography and his paintings have reached all corners of the globe and crossed genres, influencing the aesthetic of popular metal music. His surreal horror art lives on as a witness to what must have been in this Polish artist.

Take a look at our Beksiński paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Beksiński Burn His Art?

Yes. In later years, Polish artist Beksiński become quite critical of his earlier creepy sketches, and in 1977, he began burning much of it, prior to his move to Warsaw. Unfortunately, no one knows why, or even what this destroyed surreal horror art might have looked like.

Did Beksiński Make Digital Art?

Yes. In the 1990s, Beksiński became interested in the possibilities of digital art and even resumed photography, using new software like Photoshop to manipulate his images. However, he soon saw the limitations of these types of media and by the 2000s, he had returned to painting.

What Does Beksiński Have to Do with Metal Music?

Beksiński’s surreal horror art and creepy sketches became extremely popular with a new generation of goths and emos, which greatly impacted their music and culture. The nightmare artist has come to define the contemporary heavy metal aesthetic.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Zdzisław Beksiński – Works of the Dystopian Surrealism Artist.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. March 22, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/zdzislaw-beksinski/

Anthony, J. (2022, 22 March). Zdzisław Beksiński – Works of the Dystopian Surrealism Artist. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/zdzislaw-beksinski/

Anthony, Jordan. “Zdzisław Beksiński – Works of the Dystopian Surrealism Artist.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, March 22, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/zdzislaw-beksinski/.