Dada Art – When Art Defies Reason and Purpose

What is Dadaism art? The Dada art movement was part of the avant-garde scene in Europe, and emerged in Zürich, Switzerland in the early 20th century. The Dada movement in New York took off around 1915, and Parisian Dadaists flourished after 1920. Dada artists remained popular until the mid-1920s, after which the movement’s activities began to slow down.

What Is Dadaism Art?

The Dada movement, which arose in response to World War I, was comprised of artists who disregarded the rationality, logic, and aesthetics of a capitalist society, preferring to express absurdity, insanity, and anti-bourgeois statements in their Dadaist artworks. The Dada art movement encompassed collage, cut-up text, sculpture, and Dadaism poetry. Dada artists voiced their disillusionment with war, violence, and patriotism, and they remained politically allied with radical left-wing politics.

The History of the Dada Art Movement

Dada originated during a period when literary and artistic movements such as Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism were based primarily in France, Italy, and Germany. Yet, unlike these previous movements, the Dada movement was able to build a broad base of supporters, resulting in an internationally recognized style. The Dada art movement’s followers lived in cities all over the world, including Zürich, New York, Berlin, and Paris. Regional distinctions included a focus on political criticism in Berlin and literature in Zürich. The Dada art movement was loosely structured, with no hierarchy, however, some notable Dadaists produced manifestos that served to outline their objectives.

On the 14th of July, 1916, Ball released the foundational Dada Manifesto, while Tzara authored a second Dada manifesto in 1918, which is regarded as essential Dadaist literature.

Tzara’s manifesto emphasized the idea of “Dadaist disgust” – the dichotomy inherent in avant-garde artworks between criticizing and affirming modernist reality. Modern culture and art are viewed as a sort of fetishization in which the commodities of consumerism are picked to fill a hole, much like a taste for sweet things. The Dada art movement intentionally provoked shock and outrage and Dadaist publications and exhibits were banned, with some of the Dada artists even facing imprisonment. These acts of provocation were part of the entertainment, but as time passed, expectations from the audience exceeded the Dada movement’s ability to meet them.

Dada Art in Zürich

There is considerable debate over where the Dada art movement originated. Most art historians and people who lived during this time period agree that the Dada movement was prompted by the Cabaret Voltaire bar in Zürich, which was co-founded by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, a cabaret singer and poet. According to some accounts, Dada originated in Romania as an extension of a flourishing creative tradition that traveled to Switzerland when a number of Jewish modernist artists, such as Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara, and Arthur Segal, arrived in Zürich. Prior to World War I, comparable art appeared in Bucharest and other Eastern European towns; it is possible that the presence in Zürich of artists like Janco and Tzara was the likely impetus for Dadaism art in the region. Cabaret Voltaire was named after Voltaire, the French philosopher whose work Candide (1759) ridiculed religious and intellectual doctrines of the day.

Tzara, Ball, Janco, and Jean Arp attended the opening night. These creatives, along with others such as Sophie Taeuber, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Hans Richter, began putting on shows at the Cabaret Voltaire in order to convey their displeasure with wars and the factors that fueled it through their artworks. The artists settled in politically neutral Switzerland after fleeing Romania and Germany during World War I. They utilized abstraction to challenge the political, social, and cultural concepts of the moment, as well as shock art, and “vaudevillian excesses” to undermine the traditions they argued had brought on the Great War. The Dadaists saw such concepts as a result of bourgeois society, which was so indifferent that it would sooner wage war against itself than confront the established systems.

Janco’s costume and mask designs, influenced by Romanian traditional art, made the horrors of their era, and the debilitating atmosphere, more apparent, according to Ball.

A balalaika orchestra played charming folk music to accompany the presentations. Arrhythmic drumming and jazz, both influenced by African music, were popular at Dada movement gatherings. Hugo Ball relocated to Bern after the cabaret closed, and Dadaist activities shifted to a new gallery. Tzara initiated an all-out effort to disseminate Dada ideals. He swamped Italian and French writers and artists with letters, soon establishing himself as the Dadaist leader and strategist. Starting in July 1917, Zürich Dada, with Tzara at the lead, produced the literary and art periodical, Dada, with five issues from Zürich and the final two issues from Paris. Other Dada artists, including Philippe Soupault and André Breton, formed literature groups to actively extend Dada’s reach. After the end of the World War in November 1918, the majority of the Dada artists in Zürich departed for their home countries, while others initiated Dada activities in other regions. Other Swiss native Dada artists, like Sophie Taeuber, would stay in Zürich into the 1920s.

Dada Art in Berlin

Raoul Hausmann, who was instrumental in establishing Dada in Berlin, wrote the manifesto Synthetic Cino of Painting (1918), in which he denounced Expressionism and the art critics who supported it. Dada was envisioned as an antithesis to art genres such as Expressionism, which appeal to the emotional condition of the viewer. In Hausmann’s vision of Dada, new creative approaches would allow for fresh and impulsive artistic ideas. The fragmented utilization of real-world impulses allows for a substantially different portrayal of reality than previous art forms. Compared to other Dada centers, the movement in Germany was not as vehemently anti-art.

Their actions and art were more social and political in nature, with caustic propaganda and manifestos, satire, public protests, and political activities.

Berlin’s extremely war-torn and politicized atmosphere had a significant effect on the concepts of the Berlin Dadaists. New York, on the other hand, owes its more philosophical, less political nature to its geographical separation from the conflict. According to Dadaist Hans Richter, who himself felt alienated from the other Berlin Dadaists, there were several distinguishing features of the Berlin Dada movement, including its political aspect and breakthroughs in artwork and literature; psychological freedom, which encompassed the abolition of just about everything; and participants who were intoxicated with their own power in a manner that had no connection to the actual world, with individuals who would even turn their defiance and anger against one another.

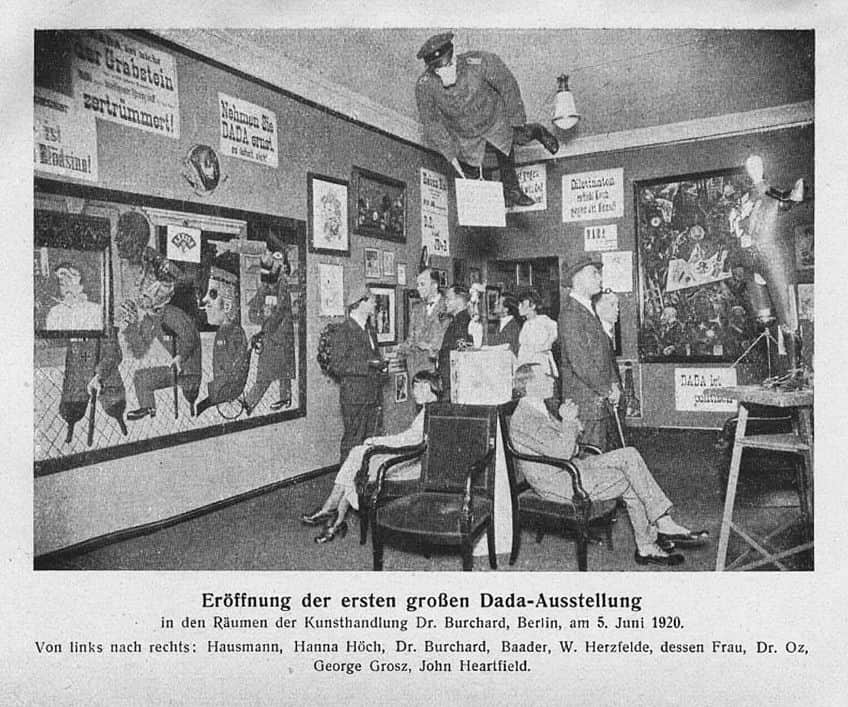

Huelsenbeck delivered his first Dadaist speech in Berlin in February 1918, as the Great War was nearing its conclusion, and later that year published his own Dada manifesto. George Grosz and Hannah Höch utilized Dada to convey communist sentiments after the October Revolution in Russia. During this time, Grosz, Höch, John Heartfield, and Hausmann pioneered the photomontage technique, and the earliest large collages were created by Johannes Baader. After the war, in the summer of 1920, the artists hosted the First International Dada Fair. The exhibit featured art by Francis Picabia, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Jean Arp, Johannes Baargeld, and Rudolf Schlichter, in addition to the main members of Berlin Dada. Over 200 paintings were displayed, but despite high admission prices, the show made a loss, with only a single sale recorded.

Dada Art in New York

New York City, like Zürich, was a sanctuary for artists and writers fleeing the First World War. Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp met Man Ray, an American artist, shortly after they arrived from France in 1915. They had established themselves as the epicenter of intense anti-art activity in the United States by 1916. Beatrice Wood, an American studying in France, and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven soon joined them. Arthur Cravan, who was attempting to evade compulsory military service in France, was also in New York for a while. Much of the American Dadaist activity occurred at 291, Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, as well as Walter and Louise Arensberg’s residence.

These New York artists, despite their lack of formal structure, referred to their acts as Dada, although they did not publish any manifestos.

They challenged culture and art with journals such as Rongwrong, The Blind Man, and New York Dada, criticizing the traditionalist framework of museum art. The New York Dadaists lacked the cynicism of European Dada, instead being fueled by humor and a large dose of irony. During this period, Duchamp started displaying his “readymades” like a bottle rack and was also involved with the Society of Independent Artists. He submitted the now-infamous Fountain (1917) urinal, for that year’s exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, but it was rejected. Initially derided by the arts community, it has subsequently been practically immortalized as one of the most iconic modernist sculptures.

However, there is still much controversy over whether Duchamp had the right to claim ownership of the idea, as he had revealed in a letter to his sister that a female friend had brought the urinal to Duchamp and had signed it with her pseudonym, “Richard Mutt”. During the Dadaist period, Picabia’s travels linked groups in Zürich, New York, and Paris. From 1917 through 1924, he also published the Dada monthly 391 in New York City, Barcelona, Paris, and Zürich. By 1921, the majority of the original artists had relocated to Paris, where the Dada art movement experienced its final phase.

Dada Art in Paris

Tristan Tzara, who exchanged Dadaism poetry, letters, and magazines with André Breton, Guillaume Apollinaire, Clément Pansaers, Max Jacob, and other French critics, authors, and artists, kept the French avant-garde informed of Dada events in Zürich. Since musical Impressionism’s emergence in the city in the late 19th century, Paris has arguably been the world’s classical music capital. Erik Satie, one of its exponents, teamed with Cocteau and Picasso on Parade, a bizarre and provocative ballet. It created a stir when it was first presented in 1917, but in a different manner than Stravinsky’s ballet had around five years earlier.

This was a performance that clearly mocked itself, something regular ballet goers would inevitably find offensive.

When many of the early pioneers gathered in Paris in 1920, Dada art once again exploded. The Parisian Dada art movement, inspired by Tzara, soon released manifestos, organized rallies, conducted performances and issued a number of publications. Dadaism artworks were first exhibited to the public in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants in 1921. Tzara’s Dadaist production, The Gas Heart, was performed the same year, amid howls of laughter from audiences. When it was re-performed in a more professional setting in 1923, it sparked a theater riot, marking the division within the movement that would become Surrealism.

Dada Art in the Netherlands

Dadaism art in the Netherlands was founded mostly by Theo van Doesburg, who is best known for pioneering the De Stijl movement and the journal that bore the same name. Van Doesburg concentrated primarily on Dadaism poetry, and his magazine published poems by several well-known Dadaists, including Hans Arp, Hugo Ball, and Kurt Schwitters. Theo Van Doesburg and Thijs Rinsema became friends with Schwitters, and collectively they coordinated the Dutch Dada campaign in 1923, during which van Doesburg endorsed a Dada leaflet, Schwitters recited his Dadaism poetry, Vilmos Huszár displayed a mechanical dancing doll, and his wife played avant-garde pieces of music on the piano. Van Doesburg also authored Dadaism poetry but under the alias I.K. Bonset, which was discovered only after his passing in 1931.

Dada Art in Georgia, Yugoslavia, and Italy

Although the Dada movement was nonexistent in Georgia until at least 1920, a collective of poets named “Le Degré 41” created works that were similar to Dadaism poetry from 1917 to 1921. The most prominent member of this collective was Ilia Zdanevich, whose unconventional typographic designs visually echoed the Dadaists’ works. Following his trip to Paris in 1921, he worked on periodicals and gatherings with Dadaists. When Tristan Tzara was barred from conducting seminars in 1923, Zdanevich arranged for a location on his behalf. Between 1920 and 1922, alongside the emerging art movement Zenitism, there was major Dada activity in Yugoslavia, led principally by Dragan Aleksi. The Italian Dada movement, centered in Mantua, was regarded with disdain and struggled to leave an impression in the world of art.

Julius Evola was a notable member of this small movement and went on to become a prominent occultist scholar as well as a philosopher.

Dadaism Poetry and Music

In the aftermath of World War I, Dadaists utilized surprise, nihilism, pessimism, contradiction, unpredictability, subconscious impulses, and antinomianism to challenge established conventions. Tzara’s manifesto from 1920 suggested clipping words from newspapers and arbitrarily picking bits to make poetry, a method in which the synchronous cosmos itself becomes an active participant in the creation of the art. Dadaism poetry produced in this manner would be the “fruit” of the lines removed from the articles. Dadaists concentrated on poetry, notably the “sound poetry” developed by Hugo Ball.

Dadaist poems challenged traditional notions of poetry, such as form and arrangement, as well as the interaction of sound and verbal meaning. According to Dadaists, the prevailing way of articulating information degrades language and Dadaists attempted to return language to its clearest and most pure form through the destruction of language and poetic traditions. A collection of speakers performed Dadaism poetry simultaneously, resulting in a chaotic and bewildering combination of voices. Unlike groups such as the Expressionists, Dadaism did not condemn modernism and city life.

The chaotic futuristic urban environment is seen as a natural habitat for innovative ideas in lifestyle and art.

Dada’s influence extended beyond the literary and visual arts to music and sound. These movements had a substantial impact on 20th-century music, particularly on avant-garde composers located in New York, such as Stefan Wolpe, Edgard Varèse, John Cage, and Morton Feldman. Kurt Schwitters created sound poetry, while Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Francis Picabia made Dada music, which was presented at the Festival Dada in Paris on the 26th of May, 1920. Dada music was also written by composers such as Hans Heusser, Erwin Schulhoff, and Alberto Savinio.

Legacy of the Dada Art Movement

The Dada movement, while vast in scope, was unstable. By 1924, Dada had merged with Surrealism in Paris, and artists had moved on to other concepts and trends such as Social Realism, Surrealism, and other kinds of modernism. Some scholars believe that Dada was the precursor of postmodern art. Many European Dada artists had immigrated to America by the outbreak of World War II. Some died in concentration camps under Hitler, who aggressively prosecuted the “degenerate art” that he saw in Dada. As postwar hope led to the emergence of new trends in the arts and literature, the group became less active.

Dada art is often cited as an inspiration and reference by a number of anti-art, sociopolitical, and cultural organizations, such as the Situationist International group. The former Cabaret Voltaire building progressively degraded until it was occupied by a group led by Mark Divo, calling themselves Neo-Dadaists, from January to March 2002. Following their eviction, the site was transformed into a museum devoted to the history of the Dada movement. Lee and Jones’ art remains on the walls of the museum. A significant Dada retrospective was staged in Paris in 1967, and other noteworthy retrospectives have since investigated the effect of Dada on society and art.

Notable Dada Artworks

Many Dadaists claimed that the bourgeois capitalist society’s logic and rationale had pushed people to war. They rejected that worldview through creative expression that purported to defy logic and celebrate disorder and chaos. Dada was the polar antithesis of all that traditional art represented. Whereas art was preoccupied with conventional aesthetics, Dada was interested in concepts.

The movement encompassed forms such as visual arts, poetry, literature, art manifestos, theater, art theory, and graphic design, and it emphasized its anti-war sentiments through a repudiation of established art standards through anti-art cultural projects.

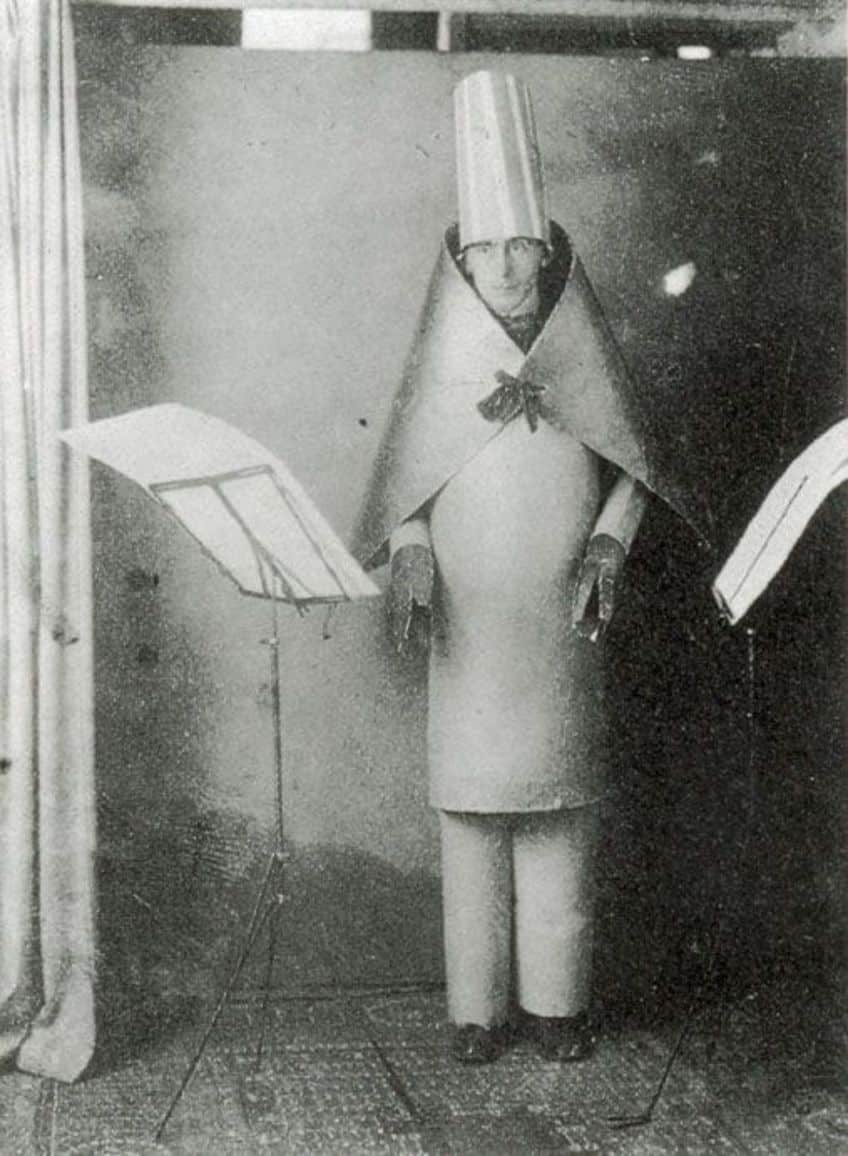

Reciting the Sound Poem “Karawane” (1916) by Hugo Ball

| Artist | Hugo Ball (1886 – 1927) |

| Date | 1916 |

| Medium | Photograph |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unspecified |

| Location | Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland |

Ball created this outfit for his presentation of “Karawane”, a sound-poem in which random words spoken in patterns produced rhythm and emotion but nothing approximating any recognized language. The resultant lack of coherence was intended to hint at the European nations’ failure to settle their diplomatic difficulties rationally, culminating in World War I – connecting the current predicament to the biblical narrative of the Tower of Babel.

Ball’s unusual clothing is intended to further separate him from his viewers and his regular surroundings, making his words even more alien and strange. His legs were wrapped in a cylinder of gleaming blue cardboard that reached up to his hips, giving him the appearance of an obelisk. Over that, he donned a massive cardboard coat, scarlet on the interior and gold on the exterior. It was secured around his neck in such a fashion that rising and lowering his elbows gave the illusion of wing-like movement.

He also sported a witch doctor’s hat with white and blue stripes.

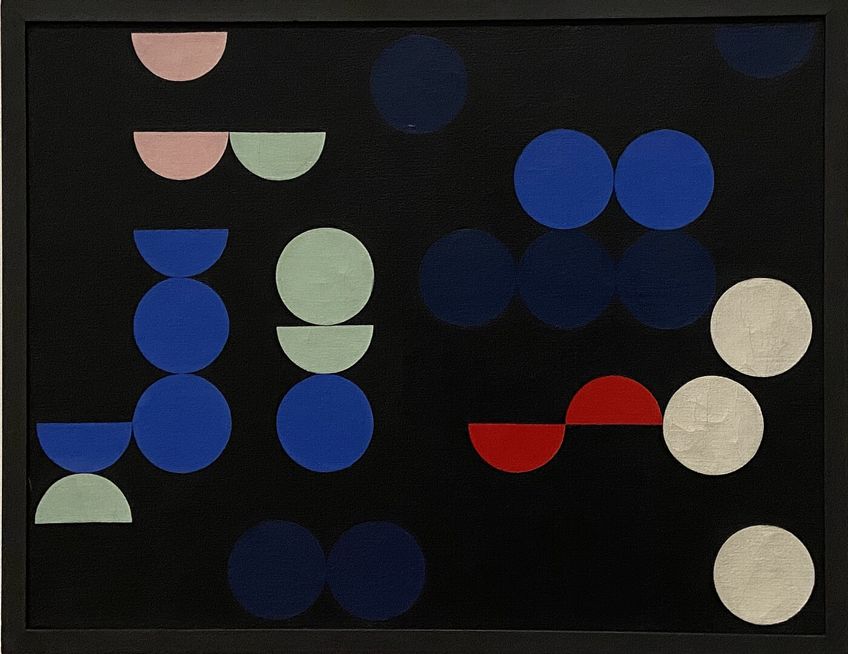

Untitled (Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance) (1917) by Hans Arp

| Artist | Hans Arp (1886 – 1966) |

| Date | 1917 |

| Medium | Cut-and-pasted colored paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 33 x 25 |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Hans Arp created a number of collages centered on chance in which he would hover above a sheet of paper, throw pieces of contrasting square colored paper on the surface of the bigger sheet, and then glue the squares wherever they landed onto the page.

The resultant design could then elicit a deeper emotional reaction, similar to the fortune telling from I-Ching coinage that piqued Arp’s curiosity, and could create a further creative spark. This approach seems to have evolved as a result of Arp’s frustration with attempts to build more precise geometric arrangements. Arp’s chance collages have come to embody Dada’s desire to be “anti-art” and their obsession with accidents as a means of challenging standard art production methods.

The absence of creative control shown in this painting would also become a distinguishing feature of Surrealism as that movement sought to discover pathways into the unconscious through which intellectual control over creation could be subverted.

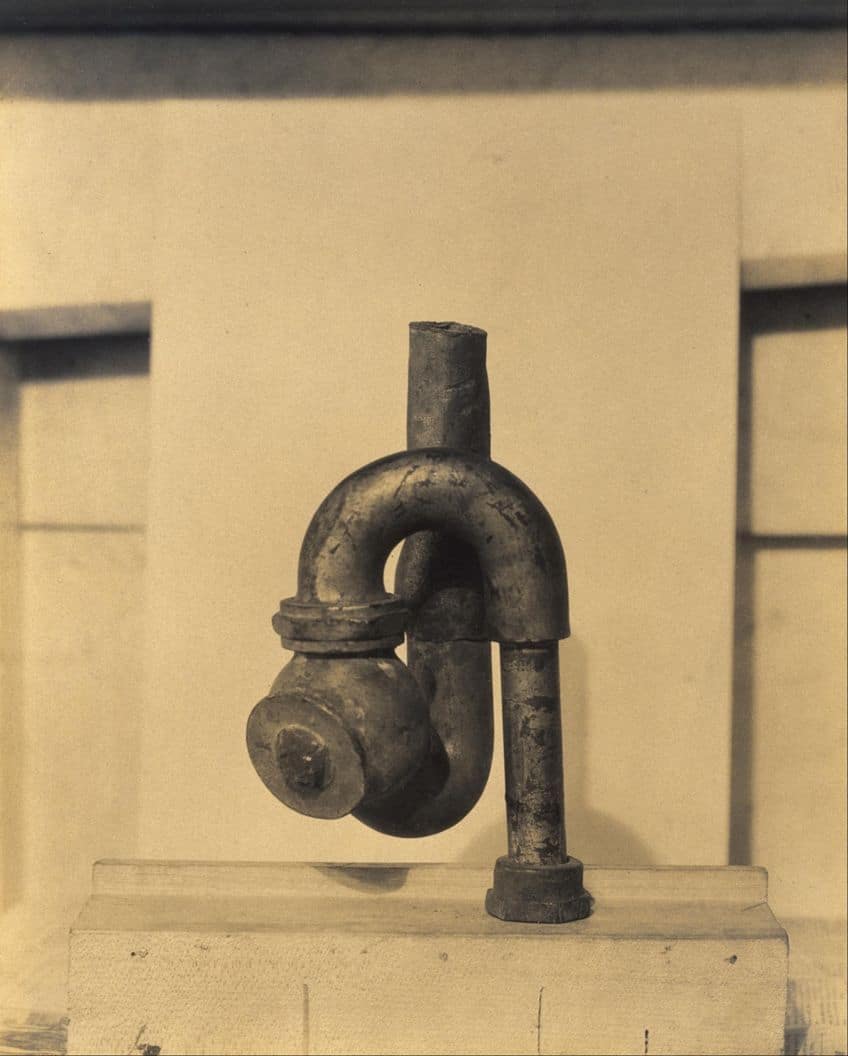

The Spirit of our Time (1920) by Raoul Hausmann

| Artist | Raoul Hausmann (1886 – 1971) |

| Date | 1920 |

| Medium | Wood, metal, leather, leatherette, and textile |

| Dimensions (cm) | 21 x 33 |

| Location | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States |

This assemblage reflects Hausmann’s dissatisfaction with the German government and its failure to effect the necessary changes to establish a better nation. It is an absurd sculptural representation of Hausmann’s idea that the typical member of a corrupt system has no more capacities than those pasted to the exterior of his skull by chance; his brain stays empty.

And hence Hausmann’s utilization of a hat maker’s dummy to portray a blockhead who can only encounter what can be evaluated with the mechanical devices glued to its head – a tape measure, a pocket watch, a ruler, a jewelry box comprising a typewriter wheel, a leaky telescopic beaker of the type used by troops during the war, brass camera knobs, and an old purse. As a result, there is little capacity for critical thought or nuance.

The dummy is a narrow-minded, blind robot with blank eyes.

Chinese Nightingale (1920) by Max Ernst

| Artist | Max Ernst (1891 – 1976) |

| Date | 1920 |

| Medium | Photomontage |

| Dimensions (cm) | 9 x 12 |

| Location | Museum of Grenoble, Grenoble, France |

Ernst’s utilization of photomontage was less ideological and more lyrical than that of other German Dadaists, with visuals created by random connections of juxtaposed photographs. He defined his approach as the systematic exploitation of the accidental or purposely induced collision of two or more mutually alienated realities in an evidently improper manner – and the lyrical spark that emerges when these worlds approach one other. Ernst created a number of collages in 1919 and 1920 that merged pictures of military technology with those of human limbs and different embellishments to create weird hybrid monsters.

As a result, the dread caused by weapons was blended with benign aspects and, in some cases, poetic titles. This cathartic release was no doubt personal for Ernst, who was maimed in the war by rifle recoil. In this piece, for instance, an oriental dancer’s limbs and fan serve as the appendages and headdress of a monster whose core is an English bomb. To give the illusion of a strange bird, an eye has been put above the brace on the side of the bomb.

The artist’s whimsy thereby erases the terror associated with explosions.

Merzpicture 46A. The Skittle Picture (1921) by Kurt Schwitters

| Artist | Kurt Schwitters (1887 – 1948) |

| Date | 1921 |

| Medium | Assemblage of wood, oil, metal, and board, with artist’s frame |

| Dimensions (cm) | 47 x 35 |

| Location | Collection of the Tate, London, United Kingdom |

This is an early type of assemblage that combines two and three-dimensional elements. The name “Merz,” which Schwitters used to characterize both his art technique and works, is a meaningless word derived from the word “commerz”.

His “Merzpictures”, also known as “psychological collages”, were created by arranging collected things – generally detritus – in simple designs that converted rubbish into magnificent art pieces. Whether it was a ticket stub, string, or chess pieces, Schwitters saw them as equivalent to any traditional art medium.

Merz, on the other hand, is neither ideological, rigid, aggressive, or political in the way that most Dada work is.

Rayograph (1922) by Man Ray

| Artist | Man Ray (1890 – 1976) |

| Date | 1922 |

| Medium | Rayograph |

| Dimensions (cm) | 23 x 17 |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

The American artist, Man Ray, spent the majority of his career in France. His works were dubbed rayographs, which were images created by physically placing items on sensitive paper and subjecting them to light. The scattered objects produce a dark trace that separates them from their original context. With their typically bizarre mixture of items and ethereal appearance, these artworks expressed Dada’s fascination with randomness and the absurd.

Ray, like other Dada artists, freed photography from its historical function as a figurative art form; in his hands, it wasn’t a mirror of nature anymore. Ray discovered the rayograph by chance: while waiting for an image to develop in the darkroom after forgetting to expose it, he placed some things on the photo paper. Tzara described them as “pure Dada works” when he first saw them, and they were an immediate success with other artists. Man Ray did not originate the photogram, but he was the most renowned.

With that, we come to the end of this article about Dada art. Not only was it a disruptive force to the status quo in its time, but many argue that it also set the stage for modern art as a whole due to its constant challenging of traditional beliefs and techniques. Dada artists originated, or at least used nearly every fundamental postmodern idea in visual and literary art, as well as music and theater. Despite its impact, however, the Dada art movement was a relatively short-lived avant-garde style.

Take a look at our Dadaism webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Dadaism Art?

Dadaism’s anti-war attitude, rejection of established aesthetic norms, and embracing of randomness, absurdity, and humor typified the movement. Dadaists attempted to question the prevailing political and cultural institutions of their day by subverting established conventions of society and art. They explored new modes of expression, such as photomontage, collage, and Dada poetry, and created works that were usually purposefully provocative and offensive.

How Was Dadaism Received?

Dadaism’s avant-garde character drew condemnation and disdain from the established art community, which was opposed to its anti-war attitude and disregard for traditional creative principles. Numerous Dadaists were politically engaged, and their artworks frequently criticized the political system, which made them subject to censorship and oppression. The Dada movement lacked a common style or vision, making it difficult for the group to create a distinct image and retain its momentum while being a loose community of artists. Dada artists generally struggled to make a living from their art, and many of them lived in abject poverty, relying on the generosity of relatives and customers.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Dada Art – When Art Defies Reason and Purpose.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 21, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/dada-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 21 August). Dada Art – When Art Defies Reason and Purpose. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/dada-art/

Davis, Liam. “Dada Art – When Art Defies Reason and Purpose.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 21, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/dada-art/.