Postmodern Art – Discover the Style of the Post Modern Period

What is Postmodernism art? The Postmodernism definition can be better understood if we look at the fundamental differences between Modernism vs. Postmodernism. The easiest way to understand Postmodern art is to define the modernist philosophy it superseded – that of the avant-garde, which was prominent from the 1860s until the 1950s. Before the Postmodern period, numerous artists were motivated by a revolutionary and forward-thinking perspective, concepts of technical optimism, and big tales of Western dominance and development.

Contents

- 1 What Is Postmodernism Art?

- 2 Important Postmodern Artworks

- 2.1 Marilyn Diptych (1962) by Andy Warhol

- 2.2 Rhythm Zero (1974) by Marina Abramović

- 2.3 Untitled Film Still #21 (1978) by Cindy Sherman

- 2.4 Untitled (I Shop Therefore I am) (1987) by Barbara Kruger

- 2.5 Apple Trees (1987) by Gerhard Richter

- 2.6 Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988) by Jeff Koons

- 2.7 Shuttlecocks (1994) by Claes Oldenburg

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Postmodernism Art?

The introduction of Pop and Neo-Dada art in postwar America signaled the birth of a counter-culture known as Postmodern art. For the following 40 years, the backlash took several creative forms, including Minimalism, Conceptual art, Video art, Institutional Critique, Performance art, and Identity Art.

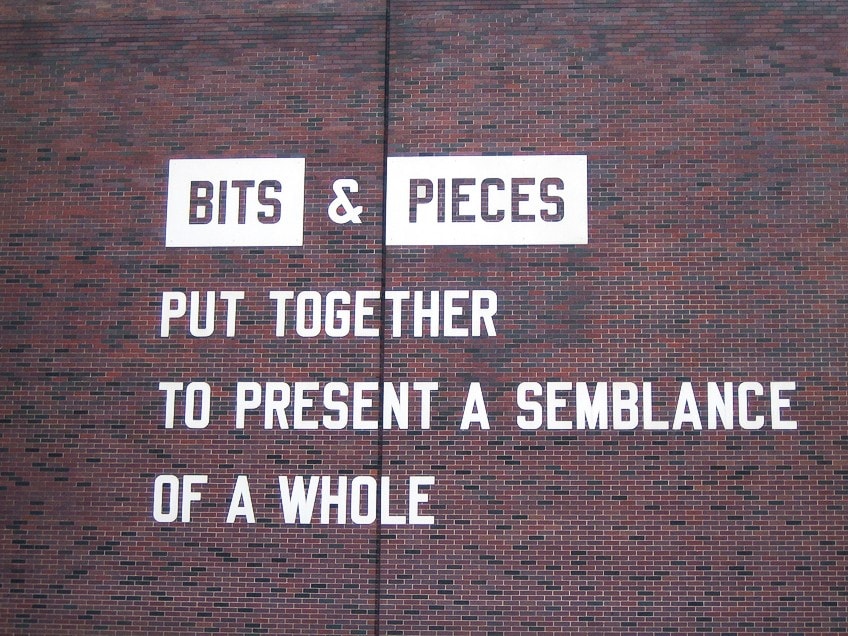

These movements are diversified and divergent, but they share specific characteristics, including an amusing and mischievous treatment of a segmented topic, the collapse of high and low cultural hierarchical structures, the eroding of notions of truth and uniqueness, and a focus on image and dramatization.

Aside from these major movements, numerous Postmodern artists continue to work in Postmodern art to this day.

The History of Postmodernism Art

Early Dada artists, who mocked the established art world with their anarchic antics and scathing performances, provided the earliest indications of Postmodernism. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until 1979, in the theorist J.F. Lyotard’s book The Postmodern Condition, that the phrase was employed in the current sense.

The phrase “Postmodern art” is typically used to refer to artistic movements that started to take shape in the late 1950s in response to the era’s alleged excesses or shortcomings.

The Modernism Period

Between the late 19th and the middle of the 20th century, the industrial revolution and identification with the optimism of contemporary life contributed to a spirit of progress and technical growth that characterized art, writing, sciences, and philosophy.

By further abstracting their topic, artists like Piet Mondrian and Paul Cézanne sought to discover a universal language of communication.

Other artists, such as Marcel Duchamp or Salvador Dalí, who emphasized the subjective and the forbidding, were viewed as anomalies in this emphasis on development and reason, and their work became forerunners of Postmodernism. In certain creative groups by the 1930s, the act of painting itself had replaced its earlier function as a tool for using line, color, and shape to convey a topic.

Clement Greenberg, an art critic and ardent supporter of modernism, was the first to notice and promote this stress on formalism in the United States.

Because they promote aesthetic purity and have a sole concentration on formalism at the cost of content, his theoretical works are frequently viewed as the opposite of Postmodernism. By the 1940s, when the Abstract Expressionists were working in New York lofts, depiction had all but disappeared in favor of a straightforward gestural expression that was more concerned with the application of paint than with story. Individuality, liberty, and a propensity for bold experimentation in quest of absolute reality or meaning were essential to the modernist avant-garde artist.

Modernism vs. Postmodernism

By the mid-century, the Western world had undergone a significant paradigm change as a result of two horrific global wars, the loss of millions of people, the destruction of communist ideals, and the use of nuclear weapons. In the post-war era, modernist optimism predominated, but today it felt obsolete, outmoded, and bound to failure. Modern art and the avant-garde no longer originated in Europe.

Consequently, New York City and the Abstract Expressionists—who were thriving in a new period of revitalized post-war capitalism—became the center of attention in the art world.

Although Greenberg steadfastly defended modernism as a noble art that all art had been inevitably progressing toward since the 19th century, his circle was nonetheless very much characterized by it. In the 1950s, America was enjoying a materialistic and cultural surge in addition to a turbulent political environment outside of this high art haven.

Young artists started to criticize Abstract Expressionism after it gained popularity because of its lack of references to both the situation of the society and the thriving popular culture that its creators were a part of.

Artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns started playing with new techniques that took and copied images from the mass culture that was all around them, inspired by these emotions and the need to make art that addressed ordinary life. They would later be affiliated with the Neo-Dada movement, which was probably the first authentically Postmodern art trend. John Cage had an impact on these artists, and many of their attempts would inspire Minimalism and Pop art.

Postmodernism Definition and Concepts

Postmodernism lacks distinguishing traits and cannot be categorized as a unified movement. Instead, it is best to think of it as a collection of attitudes and fashions that were united in their opposition to modernity. The 1950s saw a shift in how popular culture and the media were viewed, which led to a flurry of art movements that reinstated depiction from various references and started experimenting with imagery, dramatization, stylistic codes, boundaries, inventiveness, and spectator involvement.

This pushed the boundaries of what was previously considered to be art.

Low vs. High Culture

Traditional fine arts like painting and sculpture are often referred to as having “high culture.” The phrase is frequently used by art critics to conjure notions of class, refinement, and authenticity. Additionally, it is used to set various creative forms and disciplines apart from the “low,” “kitsch,” or common culture of mass-produced goods, periodicals, television, and pulp literature that swept the nation in the post-war rampant consumerism boom.

Clement Greenberg cautioned the modernist avant-garde against affiliation with what he called philistine outpourings in his seminal 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.”

Instead, Greenberg said that artists’ issues should be saved for art that has the potential to change society. In reaction, the Postmodernists fully welcomed the “popular” and made it the focal point of their work. While the Minimalists employed industrial materials to produce repeated shapes reminiscent of the industrial production line, Pop artists copied the banal products of consumerism but used humor and sarcasm to convert these into enormous soft forms or into cultural icons.

Many artists started using the “popular” as both their topic and their medium, and commercialism was welcomed. This emphasis on “poor” culture pushed the boundaries of what constitutes art while simultaneously offering social commentary.

Spectacle and Imagery

Advertising and the mass media grew more ubiquitous in this new era of consumerism and television. For instance, the American people first saw unfiltered videos of the Vietnam War in 1968, which created a jarring contrast with their own privileged lifestyles as they watched the atrocities of war while eating dinner.

With the growing use of advertising, images on the television were reflecting a new reality, making it frequently harder to differentiate between fact and fantasy.

French philosopher Jean Baudrillard used the term “hyperreality” to describe this condition, comparing Postmodern existence to a flickering TV screen because it is instantaneous, changeable, and fractured with no underlying truth. Artists like Barbara Kruger were motivated by these novel concepts to paint the surface rather than the reality or a deeper significance.

The meaning was produced via style and spectacle rather than through content.

A camp aesthetic that took inspiration from Gothic and Baroque past forms simultaneously emerged; the more colorful, showy, and frightening it was, the more effective it was, especially in clothes and music. A notable illustration of this component of Postmodern art is Jeff Koons’ creations.

Aesthetic Codes Mixing

In opposition to the French Academy’s domination over aesthetic taste and its historical and figurative focus, modernism originally developed in 19th-century France. The avant-garde movements that came after in the early 20th century gradually got rid of all allusions to a context or topic in quest of a radical and fresh form of pure and unmediated visual expression.

With Abstract Expressionism, which supported non-representational art, this fad achieved its pinnacle.

However, painting as a medium was derided as formulaic in the decades that followed the movement, leaving little possibility for creativity. Postmodernism revived both the historic and the subjective, but with a deliberate lack of artistic integrity or consistency. As a result, several artists started rediscovering earlier forms and media, notably Postmodernism painting. Artists like Gerhard Richter juggled aesthetic norms and genres in whimsical ways, changing the meaning of existing structures and inventing new ones.

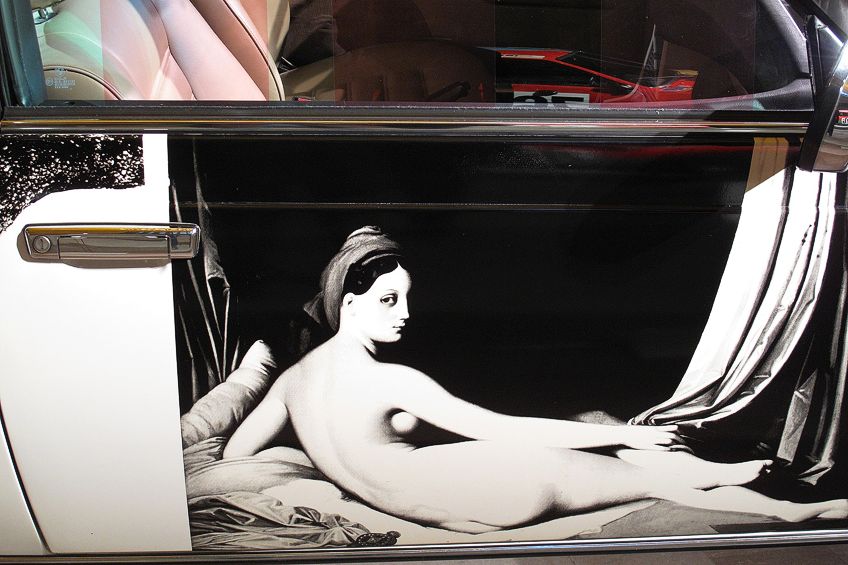

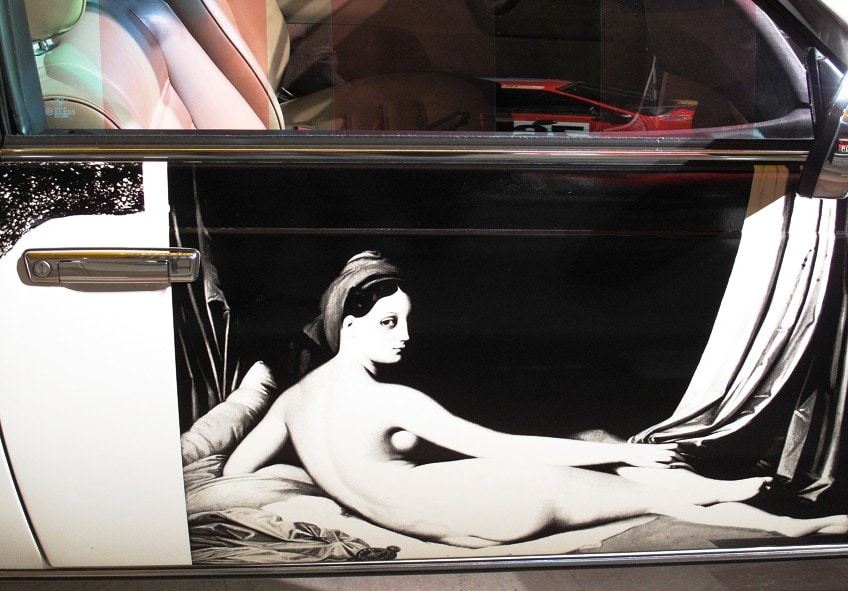

Using parody and pastiche techniques, classic concepts might be reimagined in fresh settings. Similar to how the Dadaists had done it before, other artists employed collage, assemblage, and bricolage to overlay surfaces by juxtaposing text, image, and found materials. The architectural design of the 1980s and 1990s, which mixes elements from two distinct historical periods into a visual spectacle, is a prime example of this blending of codes. The impression might be significantly improved in a movie.

New multimedia technologies presented potential, but there were also substantial crossovers between creative fields starting in the 1950s and 1960s when established classifications were abandoned.

“Anything goes” was a famous Postmodernist adage that alluded to the expanding convergence culture as well as the dissolution of the line between “good” and “poor” taste and the difficulties of valuing or evaluating works of art using conventional standards, as in the example of Jeff Koons. The processes of both art and non-art forms, including advertising, were adapted by artists, who used a variety of mediums to spread numerous themes.

Uniqueness and Authenticity

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp exhibited a urinal that was inscribed with a fictitious name and referred to it as art. He did this by making fun of the fundamental tenets upon which the institution of art had been established. An idea upheld by modernist art critique, originality and individuality traditionally provided an artwork its worth or “aura,” both in metaphorical and monetary terms.

“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, an important article by cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, published in 1936, completely reconstructed this perspective and accused influential individuals like Greenberg of being elitist.

Because mechanical replication has a lower market value and is more widely available to the general public, Benjamin argued that it can lead to the democratization of art. Benjamin’s worldview was embraced by the minimalists, performance artists, pop artists, conceptual artists, and others.

They translated his ideas into a wide variety of mediums and techniques that perverted commoditization and challenged the ideals of value and authenticity. Using screen printing, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein manufactured mugs and bags in large quantities. The curator chose how Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd’s repeating shapes were shown while Marina Abramovic, Allan Kaprow, and the Fluxus artists performed works in which the form and content were chosen by the audience rather than the artists themselves.

It was common for artists of all hues, such as Richter, Warhol, and Koons, to use photography and other imagery.

A rise in interest in the concept of collaborative authorship emerged in feminist art throughout the 1970s and again in the 1990s, undermining long-held notions of originality and creative genius that had been prevalent since the Renaissance.

Artists like Daniel Buren positioned the development of meaning at the point of contact and were more interested in the social process of art creation than the art itself. Through its performative aspect, this new practice—which later took the name Relational Aesthetics—resisted the commoditization of art and offered a potent critique of the art industry, a discipline that later became known as institutional critique.

Poststructuralism

The philosophical component of Postmodernism is a result of intellectual changes that took place in France in the second half of the 1960s. Poststructuralists including Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, and Jacques Derrida are known for their work. However, Barthes’ article The Death of the Author from 1967, in which he famously hypothesized that the author’s death must be compensated for by the birth of the reader, is what really sparked a change in the way we view and analyze art.

For Barthes, texts—whether literary or artistic—were never truly unique; rather, they were composed of “a tissue of quotes” from earlier and already-published works.

Therefore, Barthes believed that assigning an author to a piece only served to narrow its breadth while the text itself had the capacity to provide countless interpretations. The concept that each person has their own unique interpretation of a text—or, in Barthes’s words, that a text’s significance lies “not in its origin but in its destination”—has resulted in revisionist versions of a canon that was formerly dominated by the biographies of the great masters of western art. Although the author of Barthes’s essay never actually passed away, many have contested the veracity of his assertions.

His work also marked the beginning of the critical theory era, in which several “truths” (plural) contested the concept of “truth” (singular).

Pluralism

Beyond replication, appropriation, and attempts at group creation, Postmodernism sought a democratic art. Postmodernism sparked a need for a more heterogeneous approach to art by coinciding with the growth of Feminism, the battle for LGBT rights, and postcolonial theory. Many artists, like Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Kara Walker, started to approach topics from many angles.

The increased portrayal of varied, multicultural identities, as well as a humorous approach to identity and the self, were two outcomes of the collective effect on the arts.

Perhaps the earliest works by artists like Cindy Sherman or Barbara Kruger were the ones that best displayed this stereotype. It is particularly true of Sherman, whose works focus on the gap between a woman’s genuine reality and an identity created via cinema or other media. Sherman wants her audience to think about how images are made and how they may be given a fluid treatment.

Thus, Sherman’s artwork challenges the grand narratives of artwork and challenges the legitimacy of the artist.

Important Postmodern Artworks

The style was expressed through many mediums, such as Postmodernism photography, Postmodernism sculpture, and Postmodernism paintings. The assumption that a work of art has a single, innate meaning or that the artist chooses this meaning when the work is created was disproved by Postmodernism. Rather, the meaning of the work was increasingly determined by the audience, who was even invited to engage in certain performance art by certain artists.

Other artists took it a step further by producing pieces that needed help from the audience in order to start and/or finish them.

Marilyn Diptych (1962) by Andy Warhol

| Artist | Andy Warhol (1928 – 1987) |

| Date Completed | 1962 |

| Medium | Acrylic on canvas |

| Location | Tate Museum, UK |

This collection of Marilyn Monroe silkscreen prints was created using images of the actress from the movie Niagara, first in color and then in black and white. Warhol created these in the months following her passing in 1962. The artist was intrigued by both the superstar cult and death itself, and this series brought his two passions together.

The recurrence of pictures mirrors Marilyn’s constant presence in the media, while the color juxtaposed against the monochromatic that fades off to the right suggests life and death.

The overt references to popular culture (and low art) in this piece question the modernist aesthetic’s clarity, the repetitious aspect pays tribute to mass production, and the satirical play on the idea of authenticity undercuts the authority of the artist. The choice of a diptych format, which was typical of Renaissance Christian altarpieces, calls attention to the idolatry of both personalities and images in America.

All of them combine to create a piece of art that questions conventional lines separating high art from low art and expresses the significance of materialism and drama in the 1960s.

Rhythm Zero (1974) by Marina Abramović

| Artist | Marina Abramović (1946 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1974 |

| Medium | Multiples items of pain and pleasure |

| Location | Performance |

In a gallery, Marina Abramović assumed a passive pose and asked her audience to interact with her in any way they saw fit. They were presented with a variety of items, including razors and a loaded pistol, each chosen for either pleasure or pain.

She was subjected to an escalating degree of hostility during the six-hour performance after first evoking a humorous reaction, leading to violent and upsetting events.

By completely ceding authorship and power from the artist to the audience, this groundbreaking work challenged the modernist idea of the individual and independent artist figure and pioneered the Postmodern turn towards audience involvement.

This performance work was characteristic of Abramović‘s propensity to perform at the physical and mental limits of her body.

Untitled Film Still #21 (1978) by Cindy Sherman

| Artist | Cindy Sherman (1954 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1978 |

| Medium | Photograph |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art |

A young lady from the 1950s is seen in this black and white example of Postmodernism photography, framed by the tall buildings of the great metropolis. Her look is ambiguous—half resolute, part uneasy. Her outfit helps us identify the period, and we wonder whether this is a still from a movie we’ve watched.

Cindy Sherman took this shot as part of an early series in which she played with the idea of a fractured Postmodern identity by acting as both the cameraperson and the subject.

She portrays herself as an actor in each scenario, which is stylized to recall a certain genre or period that the viewer can know and relate to, even if none of these scenes are taken from a specific movie. These consequently exist as models or signs without a context, mirroring the idea of the “hyperreal” society proposed by philosopher Jean Baudrillard, in which it is hard to distinguish between real and unreal.

In its lack of authenticity, the portrayal of a fluid identity, and appropriation of historical aesthetics, Sherman’s images exhibit Postmodernism.

This television series came into existence during the second wave of feminism, which questioned how women were portrayed, notably in movies. Through her reflective method, Sherman critiques the idea of a set feminine role and questions if women must always be shown as sufferers and martyrs. Sherman paradoxically puts herself both inside and outside of this medium. She weakens the influence of female portrayals by bringing up this issue.

Untitled (I Shop Therefore I am) (1987) by Barbara Kruger

| Artist | Barbara Kruger (1945 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1987 |

| Medium | Silkscreen |

| Location | Private Collection |

The combination of discovered photographs and assertive or provocative catchphrases in a photolithograph that acquires the straightforward manner and visual structure of mass media communications and thus undercuts strict differentiations between the visuals, aesthetic, and viewing public for high art and that of marketing is a defining feature of Barbara Kruger’s work.

This is clear from the work’s bold red, black, and white color palette as well as the block typography, which reveals Kruger’s expertise in graphic design and business.

The adage “I shop therefore I am” challenges René Descartes’ aphorism “I think therefore I am,” by subverting the idea that consumerism, not human agency, now dictates identity. In other words, who you purchase, not what you think, determines who you are.

Thus, the work starkly underlines the shift toward images and spectacle: a person’s worth and identification are limited to what can be seen on the outside, including their purchases and the brands they wear.

Apple Trees (1987) by Gerhard Richter

| Artist | Gerhard Richter (1932 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1987 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Private |

In addition to working with gestural Postmodernism painting, Postmodernism sculpture, Postmodernism photography collage, and other media, Gerhard Richter is renowned for blending several aesthetic norms. When many artists turned away from painting in favor of installation art, he was one of several German artists who revitalized the form while questioning some of the fundamental presumptions underlying the idea of representation itself.

In order to concentrate on the process of painting rather than on choosing what to paint, he would borrow his subject matter from tabloids or images.

For instance, in Apple Trees, Richter creates a traditional landscape akin to those found in German Romantic landscape paintings, but he blurs the picture so that specifics and details about the landscape are not evident or even available, questioning the purpose of representational art, which is to portray.

He contends that by not imposing any restrictions on what the observer may perceive, this approach leaves room for interpretation.

Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988) by Jeff Koons

| Artist | Jeff Koons (1955 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1988 |

| Medium | Porcelain |

| Location | The Broad Art Foundation |

Michael Jackson and his pet monkey Bubbles are depicted life-size in this painting relaxing on a bed of flowers. The piece is a good illustration of the excesses in color, scale, and topic that define Koons’ style. Jackson was at the peak of his fame at the time, and Koons emphasized this by painting the figures in gold to elevate Jackson to the status of a “god-like image.”

The use of the colors white and gold also evokes Baroque, Byzantine, and Rococo art; this evocation of earlier movements and purposeful theatricality is indicative of the camp aesthetic that distinguishes the Postmodern period.

The piece, which is a part of Koons’ Banality series, is a wonderful illustration of Koons’ art’s tendency toward kitsch since it elevates the gaudy and the emotional. With this piece, Koons appears to set an intentional challenge to established standards of taste and the contemporary division between high art and pop culture, like most Postmodern artists.

Shuttlecocks (1994) by Claes Oldenburg

| Artist | Claes Oldenburg (1929 – 2022) |

| Date Completed | 1994 |

| Medium | Canvas, foam rubber, cardboard |

| Location | Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas |

With soft Postmodernism sculptures like Soft Toilet (1966), Oldenburg first explored the intersection of banality and art by recreating everyday items using cushioned substances that underscored their solid architecture. His sculptures are large-scale but are set directly on the ground, omitting the plinth often used for sculpture in order to figuratively situate the artwork in the space of the observer.

His works raise an aspect of daily life to the level of art by employing an irrationality reminiscent of Dada’s “readymades.”

A subsequent piece, Shuttlecocks was placed in front of the museum’s traditional building in Kansas City. Through these items, he emphasizes the over-the-top nature of popular or low culture in ordinary life, in this example, a straightforward sport of badminton on an expansive lawn. Oldenburg clearly articulates his viewpoint that everything can and should be deemed art in his essay from 1961, I Am for an Art.

The term “Postmodernism” refers to both the time that succeeded modernism’s prominence in both philosophy and practice in the first and second half of the 20th century as well as a backlash against its ideals and principles. The phrase connotes doubt, irony, and philosophical challenges to the notions of absolute principles and objective truth. Since there is no one Postmodern aesthetic or philosophy upon which it is predicated, Postmodernism as an artistic movement sometimes defies description. It is possible to say that it began with pop art in the 1960s and encompasses a lot of what came after, such as neo-expressionism, conceptual art, feminist art, and the Young British Artists.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Postmodernism?

Postmodernism emerged from skepticism and mistrust of reason, whereas modernism was founded on idealism and reason. It questioned the idea that there are universal facts or certainties. Postmodern art received inspiration from mid-to-late-20th-century philosophy, which promoted the idea that personal experience and how we perceive it are more tangible than abstract ideas. Postmodernism welcomed levels of meaning that were complicated and even contradictory, in contrast to modernism, which favored clarity and simplicity.

What Differentiates Modernism vs. Postmodernism?

Modernism was opposed by Postmodernism. The foundation of modernism was often idealism, a utopian view of human existence and society, and faith in development. It was considered that reality could be understood or explained using a set of fundamental universal principles or truths, such as those developed by religion or science. Instead of concentrating on topics, modernist painters experimented with form, method, and procedures because they thought they could discover a way to create art that was just a reflection of the contemporary world.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Postmodern Art – Discover the Style of the Post Modern Period.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 4, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/postmodern-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 4 August). Postmodern Art – Discover the Style of the Post Modern Period. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/postmodern-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Postmodern Art – Discover the Style of the Post Modern Period.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 4, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/postmodern-art/.