Representational Art – How Artists Capture Our World

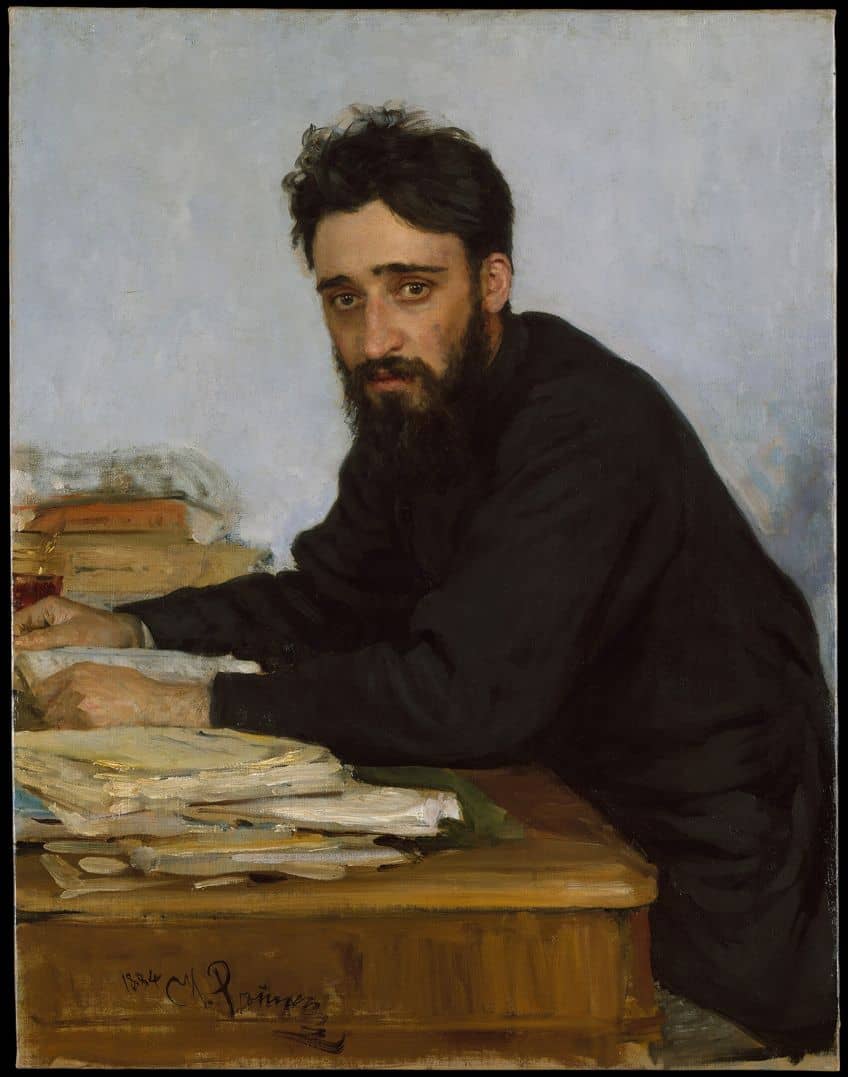

What is representational art and how does it differ from non-representational art? When we talk about representational artworks, we are talking about sculptures and paintings that look like the real-life objects that they are attempting to visually represent. However, the objects in representational drawings do not have to be life-like or realistic – just recognizable. This article will explore the representational art definition, representational and non-representational art examples, and representational artists.

What Is Representational Art?

As we have mentioned above, the Representational art definition states that the object in the artwork, no matter how aesthetically divergent from the original real-life object, is still recognizable as the said object. So, for example, a cow could be drawn out of cubes and colored blue, but you would still recognize it as a cow. On the other hand, if we look at the non-representational art definition, we will find that the elements that one can observe in a non-representational artwork do not represent anything found in the world around us, but are rather creations solely of the artist’s imagination. Not every artwork is so easily categorized, though, and if we were to imagine a scale with ultra-realism on one extremity and absolute abstraction on the other, then we will discover hybrid forms of representational abstract art somewhere in the middle as the abstract forms start to become recognizable as real-life objects. Representational artworks include traditional landscapes, still-lifes, portraiture, mythological and historical paintings, and any other type of figurative artworks, including animals, insects, etc.

The Differences Between Representational and Non-Representational Art

Another way to understand the differences between representational art and non-representational art is to view things through the artist’s eyes. Representational artists usually serve as observers, trying to accurately recreate their observations. Certainly, they do also individually “interpret” what they observe – which is why no two representational artists will portray an object or landscape in the exact same way – yet their main purpose is to examine and replicate the objects they observe.

Plein-air landscape painting, which was developed by 19th-century Impressionists, for instance, is practically always representational.

Non-representational artists, on the other hand, have different aims. Their goal is to produce a more subjective image: one that is not immediately related to any recognized item and must be interpreted as a result. This non-representational style is exemplified by the artworks of Piet Mondrian, Mark Rothko, and Sean Scully, whose works do not possess any meaning or purpose and therefore need to be solely interpreted totally by the observer.

The Origins of Representational Artworks

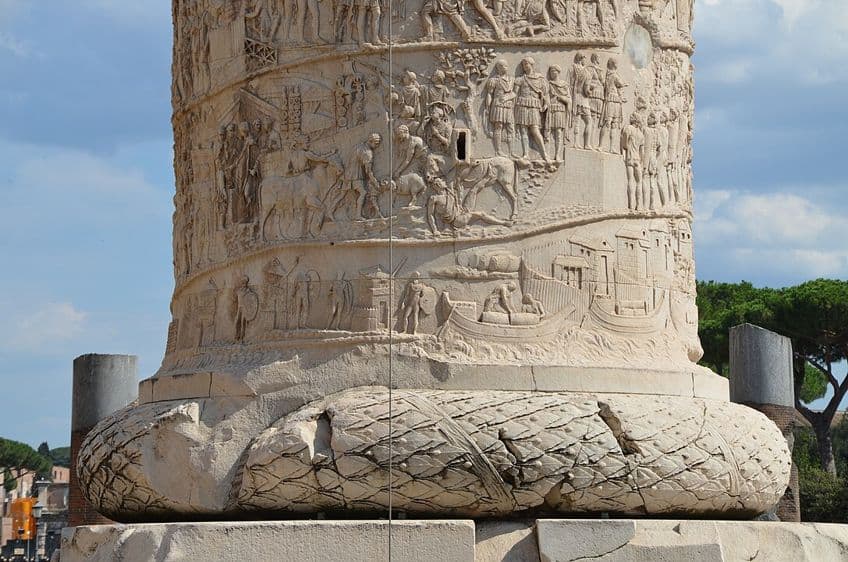

The majority of ancient art is figurative and dates all the way back to the Stone Age. Sculptures such as the many Venus figurines, as well as cave paintings from Lascaux and Altamira, are examples of early representational artworks. Modern representational artwork is heavily influenced by Greco-Roman art, as demonstrated by the Greek Sculptures produced by representational artists such as Praxiteles, Hagesandrus, Athenodoru, and Polydorus. The bas-relief on Trajan’s Column (c.106-113 CE) in Rome from the Julio-Claudian era is one of the best examples of representational Roman art. These masterpieces of Classical Antiquity served as the foundation for the subsequent Italian Renaissance, which influenced representational artists well into the 20th century. The Chinese Terracotta Army (c. 221-206 BCE), sculpted during the age of Qin Dynasty art, is possibly the finest example of representational art, despite only being undiscovered in the modern era.

Representational Artwork Styles

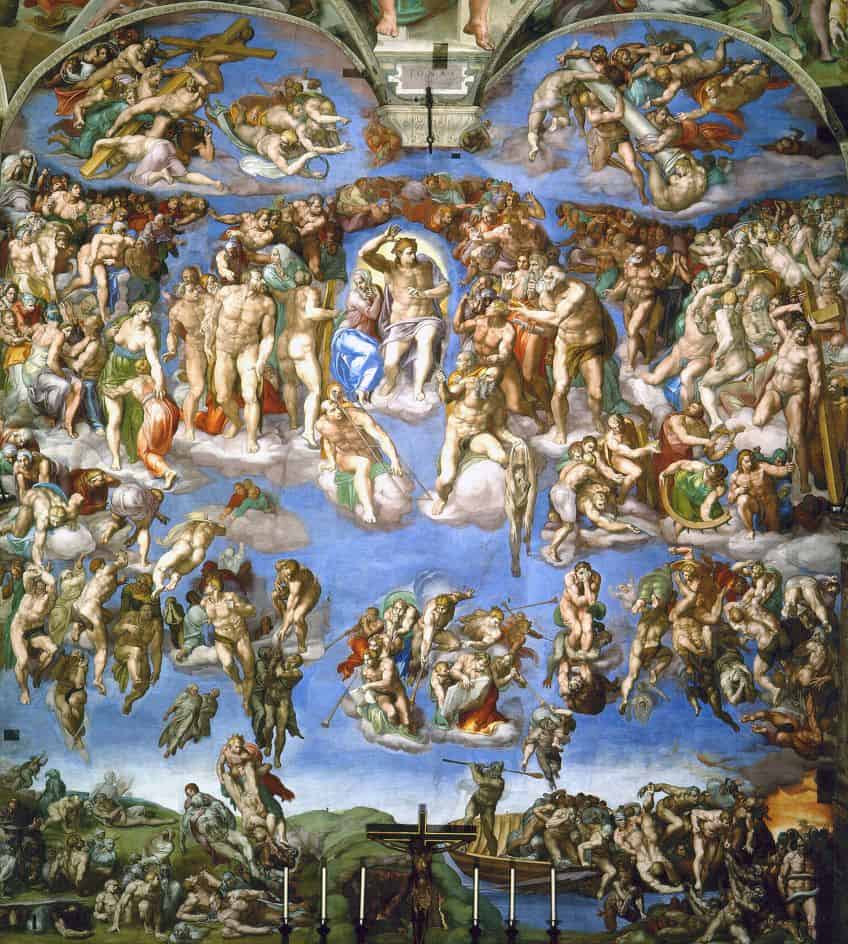

Italian Renaissance art emphasized an ‘ideal’ style of representational art, as epitomized by the sculptures of Michelangelo and Donatello. Human nudity was seen as the pinnacle of artistic expression, and idealized forms were frequently depicted and sculpted. Throughout Renaissance Florence, Venice, and Rome, there were relatively few “ugly” faces or figures on exhibit. Linear perspective techniques were developed and defined. But, throughout the Mannerism period, starting with Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment (1541), this began to change.

Human figures became less idealized and more realistically portrayed, particularly outside of Italy, where non-idealistic artwork predominated.

This was most noticeable in Holland, where the styles of Roger Van der Weyden and Jan Van Eyck gave rise to the sublime school of Dutch Realism, epitomized by the magnificent interiors produced by Jan Vermeer. Nevertheless, due to the Church’s power and the lasting impact of the Italian Renaissance, as conveyed through the influential European academies of art, it would not be until the Industrial Revolution that Realism emerged and artists started to depict the real reality of life rather than the idealized version. This had an impact on both painting techniques and subject matter. For instance, complete expression was devoted to color, as representational artists sought to portray what they observed. As a result, if a haystack looked pink in color in the fading light, it was portrayed pink.

Representational Art in the 20th Century

Throughout the last three decades of the 19th century, European representational artwork was influenced by the free-flowing techniques of the Impressionists, who nonetheless valued conventional abilities like representational drawing, color, and composition. For instance, the Impressionist draftsman Edgar Degas was one of the greatest draftsmen in art history, and John Singer Sargent, the famous Impressionist portrait painter, was a specialist of the “au premier coup” method (one precise brushstroke, without any reworking).

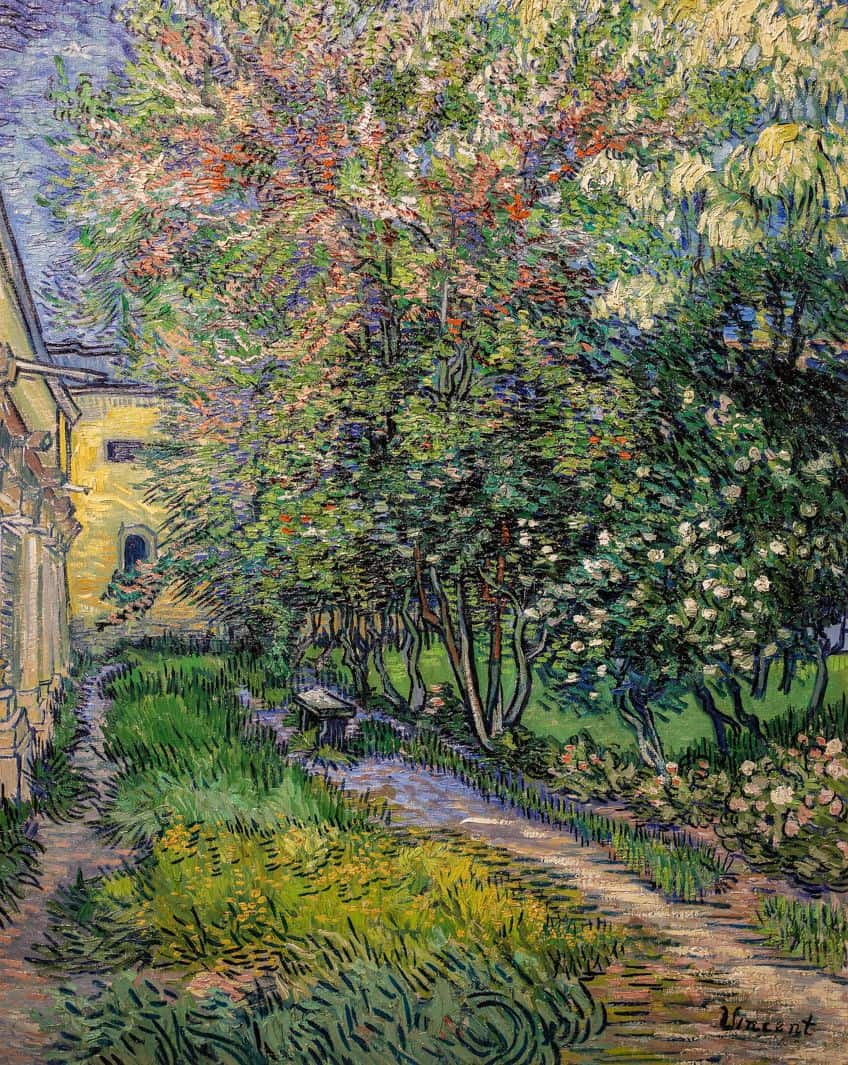

Yet, the arrival of Van Gogh in the late 1880s marked a significant shift.

Van Gogh’s striking impasto painting and extremely personalized works of art signaled the start of an Expressionist style that was subsequently evolved by the Norwegian Edvard Munch and, in particular, by German groups like Die Brucke, Der Blaue Reiter, Die Neue Sachlichkeit, and artists like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Alexei von Jawlensky, Egon Schiele, and Max Beckmann. Although early Expressionism followed a representational style (for the most part), it disregarded academic traditions in favor of a more subjective method of painting. This eventually led to a deterioration of conventional painting techniques, which, in combination with political developments at the beginning of the 20th century, resulted in the birth of post-Modernism and Abstract art. As a consequence, by the 1940s, the art world (centered in New York at the time) was experiencing the triumph of form over content.

Cubism, Picasso, and the Move Towards Abstraction

Together with the advent of German Expressionism and its core subjectivism, true-to-life art came under attack from other painters who were unsatisfied with its antiquated image and absence of intellectual potential. Yet, in their attempts to modernize art, they effectively tossed away the baby with the bathwater, a phenomenon arguably best exemplified by the works of the artist Pablo Picasso, who shone in both representational and non-representational art. Picasso focused on realistic painting in his early career, particularly during his Blue and Rose periods.

This led to his brief “African period”, during which his iconography became increasingly deformed, and then to his groundbreaking Cubism style, the disconnected shapes of which are among the most well-known instances of non-representational art.

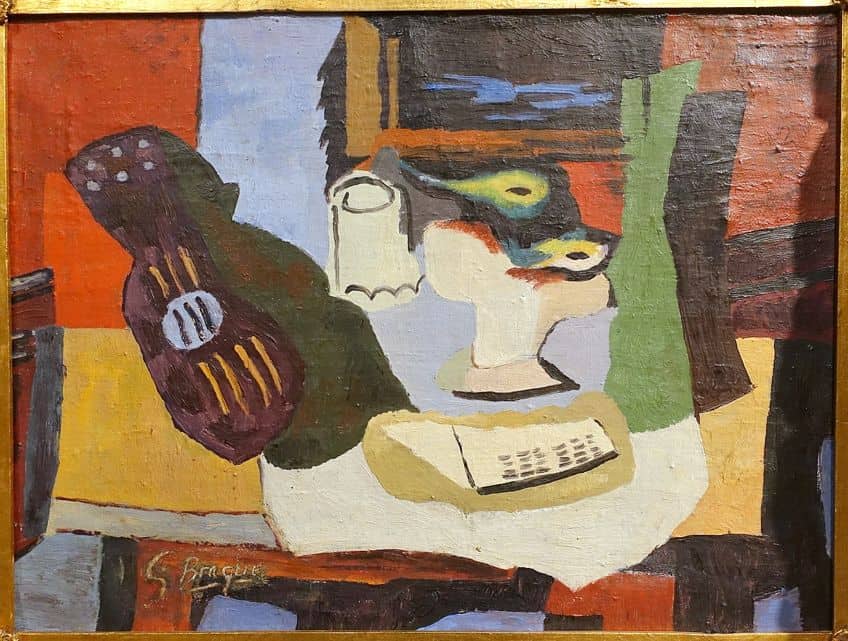

Picasso believed that realistic art had achieved its apex with the Fauvists and Impression. As a result, Picasso started to explore more abstract art forms, which he and Georges Braque regarded as more intelligent, and thus Cubism was born. Nevertheless, notwithstanding Cubism’s truly innovative nature and contributions to art history, and despite Picasso’s massive creative output during his lifetime – an oeuvre that included Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism – he was never truly engaged in pure abstraction, and most of his masterworks were arguably representational abstract art. His use of classicist language, as well as his contributions to modern art’s classical revival, were also remarkable.

The Importance of Representational Art

First and foremost, representational art is important because it serves as a standard against which artistic value may be measured. A portrait, for instance, can be evaluated based on the resemblance it conveys to the subject; a landscape can be evaluated based on its resemblance to a specific scene; a street scene can be likened to real-life; and an artwork of a dimly lit scene can be evaluated based on how well it portrays shadows and light. But, because non-representational art does not attempt to depict anything in actual life, it cannot be assessed using objective standards. As a result, the prestige of non-representational artists may be wholly reliant on the dictates of art world trends rather than demonstrated competence.

Representational art is a vital basis for all visual art since it relies on an artist’s competency in representational drawing, perspective, tone use, depiction of light, and overall composition: qualities that underlie many types of visual art.

Additionally, pupils can be instructed on these objective abilities for the benefit of everybody, not least because such training can build on, preserve, and enhance creative approaches. Because representational visuals are immediately identifiable and so perceptible, they contribute to the general public’s exposure to art. Non-representational artworks, on the other hand, may need significant expert knowledge on the part of the observer before they can be fully appreciated. This restriction sometimes functions as an unwelcome barrier between artists and the general population. None of this diminishes the important and beneficial value of abstract art. Yet, these considerations illustrate that representational artworks play an important role in the development, evaluation, and appreciation of high art and that it should be actively encouraged by competent individuals and organizations alike.

The Impact of Representational Artworks

Throughout history, representational art has had a profound effect on the art world. It has played a key role in chronicling historical events and societal conventions over the years. From prehistoric cave paintings to modern-day portraiture, representational art has functioned as a visual record of a historical period’s people, events, and locations. It has also been utilized for cultural expression.

Religious paintings from the Renaissance, for instance, featured biblical stories and functioned as a kind of religious expression for both the creator and the audience.

Numerous artistic movements, such as the Renaissance, Realism, and Romanticism, have emerged over the centuries, and these movements have inspired innumerable artists and changed the direction of art history with their unique kinds of representational art. From oil painting to photography, the goal of realistic depiction has resulted in the creation of new creative techniques and materials. Countless representational artists have used these approaches to test the limits of what is achievable in representational art.

That wraps up our look at the various representational art examples. It has long been taught as a vital skill for artists at academic art colleges. For generations, the emphasis on a realistic portrayal of the observable world has been a hallmark of art education. While representational artworks have long been a dominant influence in the art world, it has also been criticized by some who regard them as restrictive or too conventional. Representational art has thus subsequently been discarded by some creators in favor of more conceptual or abstract styles. However, it is highly doubtful that it would ever completely disappear and will continue to manifest in innovative and unique new styles.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Representational Art Definition?

Representational art is a historically prevalent style in which artists portray recognizably real things, people, or settings. The goal of representational artwork is to provide a visual depiction of something that the audience can comprehend and relate to. This art form has a longstanding tradition, beginning with ancient cave paintings and extending through the classic and Renaissance eras, right up to the present day. It can be produced in a range of mediums, including sculpture, painting, and representational drawing, and can depict the subject matter either realistically or stylized.

What Is the Non-Representational Art Definition?

Non-representational art examples can be executed using an array of mediums, such as sculpture, painting, and mixed media, and can vary in style from simple and geometrical forms to emotive and expressive brushwork. Non-representational art focuses on color, form, and texture rather than real-life things, sometimes producing compositions that are entirely aesthetic or emotive in character. This art style is distinguished by its divergence from classic representational principles such as proportion, perspective, and symmetry, and it is usually associated with current and modern artistic movements.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Representational Art – How Artists Capture Our World.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 16, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/representational-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 16 August). Representational Art – How Artists Capture Our World. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/representational-art/

Davis, Liam. “Representational Art – How Artists Capture Our World.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 16, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/representational-art/.