Mannerism Art – Exploring the Artistic Style of the Mannerism Period

What is Mannerism art? Mannerist art is a European art style that arose in the final years of the High Renaissance in Italy which spread around 1530 and lasted until the conclusion of the 16th century when it was mainly supplanted by the Baroque style. The Mannerism style comprises a wide range of methods influenced by and responding to the harmonizing principles affiliated with painters such as early Michelangelo, Raphael, Vasari, and Leonardo da Vinci. Whereas High Renaissance art stresses symmetry, symmetry, and idealized perfection, the Mannerism period exaggerates such traits, culminating in unbalanced or artificially exquisite compositions.

Mannerism Art

The Mannerist painting style, distinguished by its synthetic rather than realistic aspects, prioritized structural tensions and volatility above the harmony and purity of previous Renaissance art. Art historians continue to argue the Mannerism art definition and the stages that comprise it.

The Mannerism period is distinguished in music and literature by its extremely florid form and cerebral complexity.

Some researchers, for example, have ascribed the title to some early modern genres of literature (particularly poetry) and music from the 16th as well as 17th centuries. The word is also applied to several late Gothic artists who worked in Northern Europe between around 1500 and 1530, particularly the Antwerp Mannerists, which was a movement unconnected to the Italian tradition. The Mannerism style has also been ascribed to Latin literature by reference to the Silver Age.

Nomenclature

The term “Mannerism” originally derived from the Italian word maniera, which means “aesthetic” or “manner.” Maniera, like the English term “style,” can refer to a certain sort of style, such as a beautiful look or an aggressive style. It can also refer to an ideal that does not require qualifying, such as saying that someone “has style.”

Maniera was used by Giorgio Vasari in three contexts: to communicate a creator’s method or process of actually working; to characterize an individual or group aesthetic, such as the phrase maniera greca to allude to the Middle Ages Italo-Byzantine aesthetic or merely to Michelangelo’s maniera; and to confirm a favorable ruling of aesthetic merit.

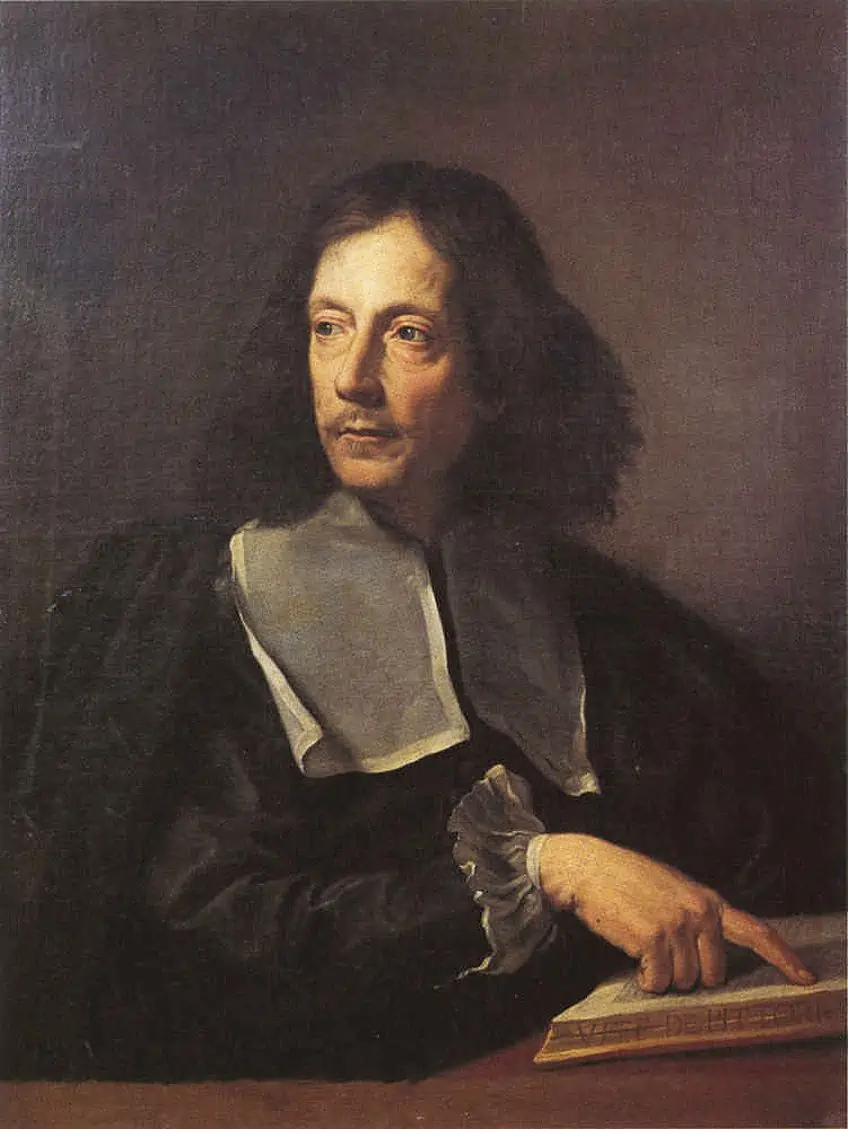

Vasari was also a Mannerist painter, and he referred to the era in which he produced as “modern style.” According to James V. Morillo, “bella maniera” authors strove to outdo Petrarch’s sonnets in virtuosity. This concept of bella maniera implies that creators who were inspired copied and improved on their predecessors rather than approaching nature directly. In summary, bella maniera took the finest from a variety of sources and synthesized it into something entirely unique.

“Mannerism” as a style descriptor is difficult to define. It was coined in the early 20th century by Swiss scholar Jacob Burckhardt and made popular by German art historians to classify the supposedly unclassifiable craftsmanship of the Italian 16th century.

These were paintings that no longer exhibited the harmonious and sensible approaches affiliated with the High Renaissance. The term “High Renaissance” referred to a time characterized by symmetry, grandeur, and the restoration of ancient antiquity.

During the 16th century, the term “Mannerism” was employed to remark on social behavior, to communicate a polished virtuoso character, or to denote a specific method. Later authors, however, including the 17th-century Gian Pietro Bellori, used la maniera as a disparaging word for the supposed degradation of art following Raphael, particularly in the 1530s and 1540s.

Work historians have often used the phrase since the late nineteenth century to characterize artwork that followed Renaissance classicism and predates the Baroque. Historians disagree on whether Mannerism is a genre, a school, or a period; yet, the word is still widely used to describe 16th-century European culture and art.

Origin and Development of the Mannerism Style

By the conclusion of the High Renaissance, creatives were experiencing a crisis: it appeared that all that could be accomplished had already been accomplished. There were no further technical or non-technical issues to be resolved.

The precise understanding of anatomy, light, physiognomy, and the way people express emotions in attitude and gestures, as well as the inventive usage of the physical figures in figurative composition and the delicate gradation of tone, had all reached near perfection.The creatives needed a fresh aim, and they looked for new techniques.

Mannerism began to emerge in this era. Between 1510 and 1520, the new style emerged in either Rome or Florence or perhaps both cities at the same time. This time has been regarded as a “logical result” of Andrea del Sarto’s, Michelangelo’s, and Raphael’s work.

Michelangelo established his unique style at a young age, a highly distinctive one that was initially praised, then frequently copied and emulated by other painters of the time. His terribilità, a sensation of awe-inspiring grandeur, was one of the traits most praised by his contemporaries, and future painters strove to recreate it.

Other artists learned Michelangelo’s passionate and deeply personal style through duplicating the master’s works, which was a common approach for students to learn to sculpt and paint. His Sistine Chapel ceiling, in particular his depiction of gathered figures, served as a model for them to emulate.

Michelangelo eventually became known as one of Mannerism’s greatest role models. Young painters even broke into his home and took his artworks.

Giorgio Vasari recalled in his book that Michelangelo once said, “Those who are followers may never pass by whoever they follow.” Patrons fostered a competitive environment by encouraging sponsored artists to showcase their virtuoso skills and compete for commissions. It pushed artists to find new ways to express themselves, resulting in brilliantly lighted settings, complex costumes and compositions, exaggerated proportions, highly stylized figures, and a lack of distinct perspective.

In Florence’s Hall of Five Hundred, Piero Soderini hired Michelangelo and Da Vinci to decorate a wall. These two painters were scheduled to create side by side and contest against each other, increasing the motivation to be as creative as possible.

The Mannerism Period and the Spread of Mannerist Art

In Italy, Mannerist hubs included the towns of Rome, Mantua, and Florence. Titian’s long career as a Venetian painter exemplified a different path for Venetian art. Following the Sack of Rome in 1527, many of the first Mannerist painters who had been active in Rome throughout the 1520s fled the city. As they moved throughout the globe in search of work, their style expanded throughout Italy and Northern Europe.

As a result, Gothic became the first universal aesthetic style since the Renaissance.

Other countries of Northern Europe did not have such close interaction with Italian painters, but the Mannerism style was felt via prints and decorated books. European kings, among others, bought Italian artwork, while northern European craftsmen continued to visit Italy, spreading the Mannerism style. Individual Italian painters operating in the north gave rise to the Northern Mannerism movement.

Mannerist painting persisted outside of Italy into the 17th century. It is recognized as the “Henry II style” in France, where Rosso proceeded to create the palace at Fontainebleau and had a significant effect on architecture.

The palace of Rudolf II in Prague, and also Haarlem and Antwerp, are key continental hubs of Northern Mannerism.

Mannerism as a style category is used less frequently in English visual and ornamental arts, while local designations like “Jacobean” and “Elizabethan” are used more frequently. One example is seventeenth-century Artisan Mannerism, which refers to architecture that depends on pattern books rather than historical antecedents in Continental Europe.

The Flemish impact at Fontainebleau is particularly noteworthy, combining the sensuality of the French manner with an early form of the vanitas style that would define 17th century Flemish and Dutch painting. The pittore vago, a characterization of northern artists who attended studios in Italy and France to produce a genuinely international style, was popular at the time.

Early Theorists of the Mannerism Period

Giorgio Vasari’s views on painting can be found in the admiration he imparts on peers in his multi-volume books: he believed that attainment in artwork required refinement, the richness of invention expressed through virtuoso technique, and brilliance and research that emerged in the completed piece, all qualifications that highlighted the creator’s intelligence and the benefactor’s good sense.

The creator was no longer only a member of the St Luke’s local Guild. He now sat at court with intellectuals, philosophers, and idealists, in an environment that cultivated respect for beauty and intricacy.

Another literary figure from the time, Gian Paolo Lomazzo, made two projects: one utilitarian and one mystical that contributed to characterizing the Mannerism creator’s self-conscious attitude to his trade.

His Trattato della pittura, scoltura, et architettura (1584), for instance, serves as a guide to modern notions of decorum, which the Renaissance inherited from Antiquity but Mannerism elaborated on. Lomazzo’s systematic formulation of aesthetics, which epitomizes the more organized and scholarly methods characteristic of the late 16th century, stressed a correspondence between interior functions and the kind of decorated and sculptural decorative items that would be appropriate.

Mannerism Art Definition and Characteristics

The Mannerism style was an anti-classical movement that diverged substantially from Renaissance aesthetic ideas. Though Mannerism was first seen positively based on Vasari’s works, it was eventually regarded negatively since it was simply regarded as “a distortion of natural truth and a tedious repeating of natural formulae.”

Mannerism art, as an aesthetic moment, entails several features that are distinct and peculiar to the exploration of how art is viewed. The following is a list of numerous distinct traits that Mannerism painters made use of in their works of art.

- Mannerist art frequently included the elongation of the humanoid figure. This occasionally led to the odd imagery of certain Mannerism.

- The deformation of perspective in paintings addressed the ideas for producing a beautiful place. However, the concept of perfection was sometimes used to refer to the development of one-of-a-kind pictures. The method of foreshortening was one-way distortion was investigated. When considerable distortion was used, the image became practically hard to comprehend at times.

- Mannerism artists frequently used flat black backgrounds to create dramatic situations by presenting a full contrast of shapes. The use of black backdrops also helped to create a feeling of imagination within the subject matter.

- Many Mannerism artists were concerned with recreating the spirit of the night sky. This was done through the use of purposeful illumination, which frequently produced fantastical scenarios. Notably, extra consideration was given to the torch and moonlight in order to create dramatic situations.

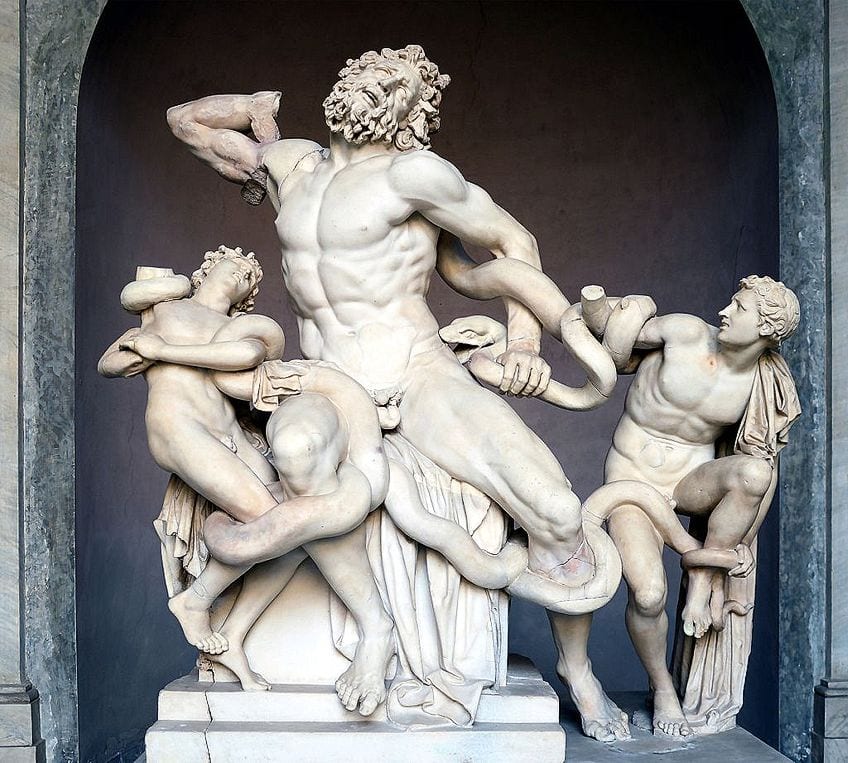

- Sculpture, which acquired prominence in the sixteenth century, had a significant impact on Mannerism. As a result, Mannerism painters frequently based their portrayals of human figures on sculptures and prints. This enabled Mannerism painters to concentrate on creating depth.

- Mannerism was notable for its emphasis on crisp contours of figures. This distinguished it from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The figure outlines frequently enabled for more care and attention.

- Mannerism painters disregarded Renaissance ideals, particularly the method of the one-point view. Rather, there was a focus on ambient effects and perspective distortion. Mannerism’s use of space, on the other hand, favored crowded compositions with different forms and figures or bare compositions with a focus on black backgrounds.

Mannerism painters frequently represented a distinct form of movement connected to serpentine poses. This was as a result of their importance in the topic of human movement. Due to their often-unstable motion figures, these positions frequently foreshadow the motions of future positions. Furthermore, this approach contributes to the artist’s form exploration.

Important Mannerist Artists

In their paintings, several Mannerisms used the sfumato technique, which is defined as “the portrayal of soft and fuzzy outlines or surfaces,” to depict light flowing. A distinguishing feature of Mannerism was that, in addition to experimenting with form, structure, and lighting, much of the same inquiry was given to color.

Many artworks experimented with clean and vivid colors of greens, blues, pinks, and yellows, which at occasions distract from and at others complement the overall design of the artworks. Furthermore, while rendering skin tone, painters would frequently focus on creating excessively creaming and light complexions, as well as using blue undertones.

Jacopo da Pontormo (1494 – 1557)

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 24 May 1494 |

| Date of Death | 2 January 1557 |

| Place of Birth | Pontorme, Italy |

Jacopo da Pontormo’s artwork is considered to be one of the most significant contributions to Mannerism. He typically took inspiration for his subject material from religious themes; greatly influenced by Michelangelo’s works, he regularly alludes to or employs sculptural forms as templates for his compositions.

The representation of gazes by diverse characters, which frequently lance out at the spectator in numerous directions, is a well-known characteristic of his work.

Pontormo, who was devoted to his art, frequently voiced concern about its excellence and was proven to work carefully and slowly. His oeuvre is greatly regarded since he influenced artists such as Agnolo Bronzino and the aesthetic aims of late Mannerism.

Agnolo Bronzino (1503 – 1572)

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 17 November 1503 |

| Date of Death | 23 November 1572 |

| Place of Birth | Florence |

Agnolo Bronzino was a disciple of Pontormo, whose manner was very significant and sometimes perplexing in determining the provenance of several artworks. Throughout his tenure, Bronzino also worked as a production designer for Vasari’s performance “Comedy of Magicians,” for which he painted several portraits.

Bronzino’s art was in high demand, and he achieved considerable success when he was hired as a royal artist for the Medici family in 1539.

The portrayal of milky complexions was a distinct Mannerism feature of Bronzino’s art. Bronzino depicts a sensual encounter in Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time, which leaves the observer with more questions unanswered. Cupid and Venus are virtually engaged in a kiss in the foreground, then halt as if caught red-handed. Above the duo are legendary characters, Father Time on the side, who draws back a curtain to unveil the pair, and the goddess of the darkness on the left.

A collection of costumes, a hybrid monster with the traits of a woman and a snake, and a man shown in agony are also included in the piece. Many ideas exist regarding the picture, such as that it depicted the hazards of syphilis or that it served as a courtroom game.

Mannerism is a European art style that arose in the late years of the High Renaissance in Italy about 1530 and flourished until the end of the 16th century when it was mostly supplanted by the Baroque style. Mannerism is a broad spectrum of approaches influenced by and reacting to the harmonizing ideas associated with artists such as early Michelangelo, Raphael, Vasari, and Leonardo da Vinci. Whereas High Renaissance art emphasizes symmetry, symmetry, and idealized perfection, Mannerism exaggerates such characteristics, resulting in imbalanced or overly exquisite compositions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Mannerism Art Style?

The synthetic rather than realistic characteristics of the Mannerism painting style emphasize structural tensions and volatility above the peace and purity of preceding Renaissance art. In music and literature, the Mannerism period is defined by its exceedingly florid form and mental intricacy. Art historians continue to argue the Mannerism art definition and the stages that comprise it.

What Is the Mannerism Art Definition?

The term is also attributed to a group of late Gothic painters who worked in Northern Europe between 1500 and 1530. They were most notably the Antwerp Mannerists, which was a movement unrelated to the Italian style. By referring to the Silver Age, the Mannerism style has also been applied to Latin literature. Mannerism is a broad spectrum of approaches influenced by and reacting to harmonizing ideas.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Mannerism Art – Exploring the Artistic Style of the Mannerism Period.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. January 26, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/mannerism-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 26 January). Mannerism Art – Exploring the Artistic Style of the Mannerism Period. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/mannerism-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Mannerism Art – Exploring the Artistic Style of the Mannerism Period.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, January 26, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/mannerism-art/.