New Objectivity Art – A Return to Detached Realism in Art

In the records of art history, the New Objectivity movement, often referred to as “German New Objectivity” or “Neue Sachlichkeit” in its native tongue, stands as a pivotal chapter that emerged in the turbulent aftermath of World War I. Emerging as a response to the chaos and disillusionment of its time, the New Objectivity movement transcended conventional artistic boundaries, producing works that reflect a stark, sober, and often unsettling portrayal of the human condition. In this exploration of the New Objectivity movement, we delve into the origins, key artists, and lasting impact of this transformative period in art history, where raw truth and unflinching observations took precedence over aesthetic idealism.

What Was the New Objectivity Movement?

The New Objectivity movement, German New Objectivity, or “Neue Sachlichkeit” in German, was an influential art movement that was one of the artistic after-effects of World War I, primarily in Germany. It gained prominence during the 1920s and early 1930s. This artistic movement was characterized by a sharp departure from the expressive and often idealized styles of the preceding Expressionist movement. Instead, New Objectivity artists sought to depict the world with a sense of detachment, objectivity, and a focus on capturing the harsh and unembellished realities of the time.

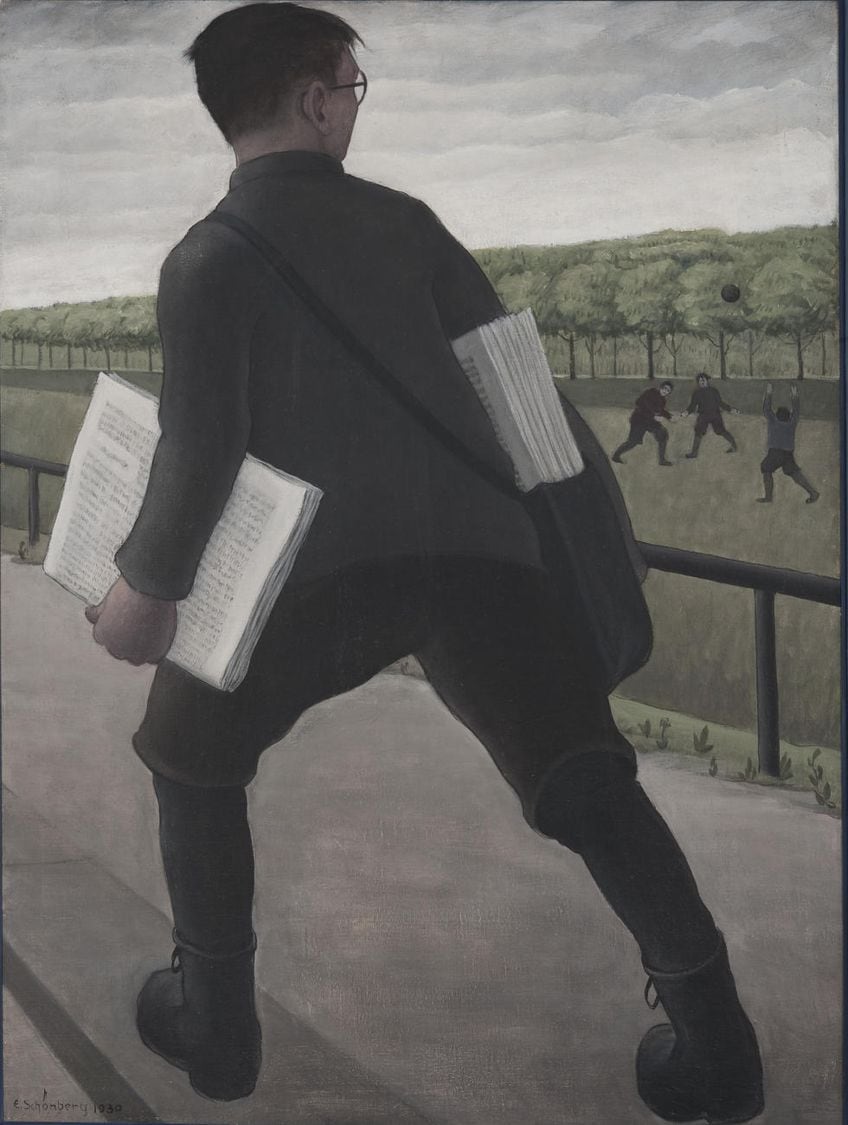

New Objectivity encompassed various artistic mediums, including painting, photography, literature, and graphic design. Prominent artists of the movement included Otto Dix (1891 – 1969), George Grosz (1893 – 1959), Max Beckmann (1884 – 1950), and Christian Schad (1894 – 1982), among others. While New Objectivity was deeply rooted in the Weimar Republic and its tumultuous political and social climate, its influence extended beyond Germany, leaving a lasting impact on modern art and shaping the trajectory of artistic expression in the 20th century.

German New Objectivity’s Origins and Development

The New Objectivity movement was deeply intertwined with the complex socio-political context of the Weimar Republic, the art world of the time, and the broader European artistic landscape. The movement emerged as a reaction to the idealism and emotional intensity of the Expressionist movement, which had dominated the German art scene before and during the war. Expressionism, with its focus on subjective emotions and distorted forms, was seen by many as out of touch with the harsh realities of post-war Germany.

The devastation of the war, economic instability, and the social upheaval that followed created an environment in which artists sought new ways to engage with the world.

Within the socio-political context of the Weimar Republic, New Objectivity found fertile ground. The Weimar Republic, established in 1919, was a fragile and stormy democratic experiment. It faced numerous challenges, including economic crises, political extremism, and social disparities. This environment of uncertainty and disillusionment fostered a desire for a more critical and objective portrayal of society.

The art world of the time was marked by a diverse range of artistic movements and ideologies, from Dadaism to Surrealism. These movements, often driven by a sense of experimentation and avant-garde spirit, contributed to an atmosphere of artistic exploration and innovation. New Objectivity artists sought to distinguish themselves within this milieu by returning to a more traditional and realistic style, emphasizing clarity, precision, and an unfiltered representation of contemporary life.

The Evolution of New Objectivity

Over time, the New Objectivity movement developed in several directions. While it was primarily associated with painting, it also found expression in photography, literature, graphic design, and even architecture. Artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz, through their scathing depictions of war and the corruption of society, created a visual language that both critiqued and reflected the times.

As the 1920s progressed, the movement diversified further. Some artists began to explore the human form and portraiture, creating haunting and sometimes disturbing images that probed the depths of human psychology.

Others focused on the urban environment, depicting the stark realities of city life, from crowded streets to decadent nightlife. However, the rise of the Nazi regime in the early 1930s marked a turning point for the movement. The Nazis denounced New Objectivity as “degenerate art” and suppressed its practitioners, leading many artists to either go into exile or conform to the regime’s artistic dictates.

Technical Characteristics of New Objectivity: Precision and Objectivity in Art

The New Objectivity movement represented a significant departure from the expressive and emotionally charged styles of the preceding Expressionist movement. Instead, New Objectivity artists sought to depict the world with a sense of neutrality, accuracy, and a devotion to capturing the stark and unadorned realities of the era. In this section of the article, we delve into the technical characteristics that defined New Objectivity, examining the artistic techniques and principles that set it apart as a pivotal chapter in the history of modern art.

Precision and Detail

One of the most striking technical characteristics of New Objectivity was its emphasis on precision and meticulous detail. Artists associated with the movement displayed a remarkable commitment to exactness in their representations. This does not necessarily mean realism, but rather an exactness in relation to Expressionism which was not interested in clear lines and forms. New Objectivity artists often employed techniques such as finely rendered brushwork, meticulous draftsmanship, and a keen eye for proportion and perspective.

This precision extended to both the portrayal of human subjects and the depiction of inanimate objects, architecture, and urban landscapes.

Clarity and Composition

New Objectivity artists favored clear and well-structured compositions. They sought to present their subjects in an organized and easily comprehensible manner, eschewing the abstract and chaotic compositions favored by some of their contemporaries. This clarity in composition allowed viewers to engage directly with the subject matter, whether it was a portrait, a still life, or a scene of urban life.

Use of Light and Shadow

Light and shadow were skillfully employed in New Objectivity artworks to enhance the sense of three-dimensionality. Artists often employed chiaroscuro techniques, emphasizing the interplay between light and dark to create a sense of volume and depth in their subjects.

This mastery of light and shadow contributed to the lifelike quality of their works, making the subjects appear tangible and present.

Realism and Objectivity

True to its name, the New Objectivity movement placed a strong emphasis on objectivity in representation. Artists aimed to present their subjects in an unembellished and unfiltered manner, eschewing idealism and romanticism. This commitment to realism (in subject) extended to the portrayal of human figures, where facial expressions and body language were often depicted with clinical accuracy, revealing the psychological and emotional states of the subjects.

Influence of Photography

The rise of photography during the early 20th century had a profound impact on the technical characteristics of New Objectivity. Many artists of the movement drew inspiration from the precise and detailed imagery captured by photography. This influence is particularly evident in the sharp focus and meticulous rendering of details seen in New Objectivity paintings.

Some artists even used photographs as reference material for their artworks, further blurring the line between photography and painting.

Satirical Elements

While New Objectivity aimed for objectivity, it was not devoid of social commentary and satire. Some artists, such as George Grosz, used a biting and caricature-like style to criticize the decadence, corruption, and social inequalities of the Weimar Republic. This satirical edge was expressed through exaggerated forms, grotesque distortions, and a sharp critique of contemporary society.

Famous Neue Sachlichkeit Artists

In this section, we embark on a journey through the lives and works of the most famous Neue Sachlichkeit artists, individuals who deftly wielded their brushes to capture the unadorned truths of their time. These visionaries, each with their unique styles and perspectives, collectively contributed to the movement’s enduring legacy.

This legacy continues to resonate in the world of art and beyond.

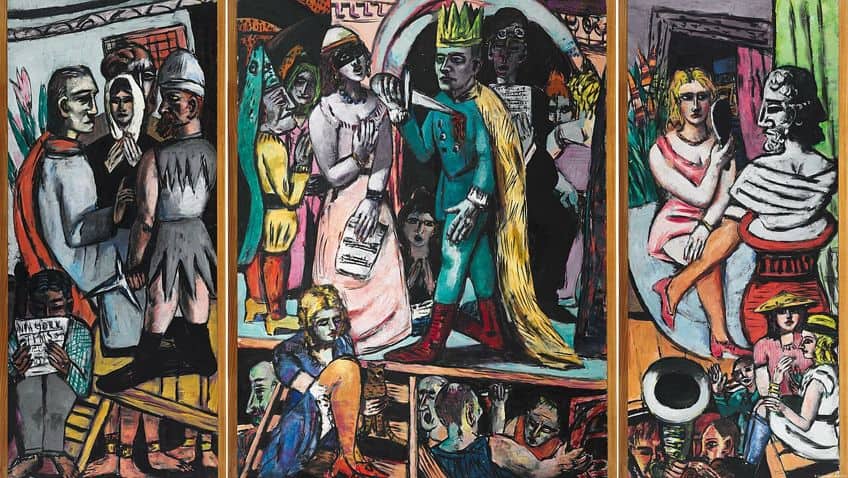

Max Beckmann (1884 – 1950)

| Date of Birth | 12 February 1884 |

| Date of Death | 27 December 1950 |

| Place of Birth | Leipzig, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Periods | Expressionism, Modern art, and New Objectivity, |

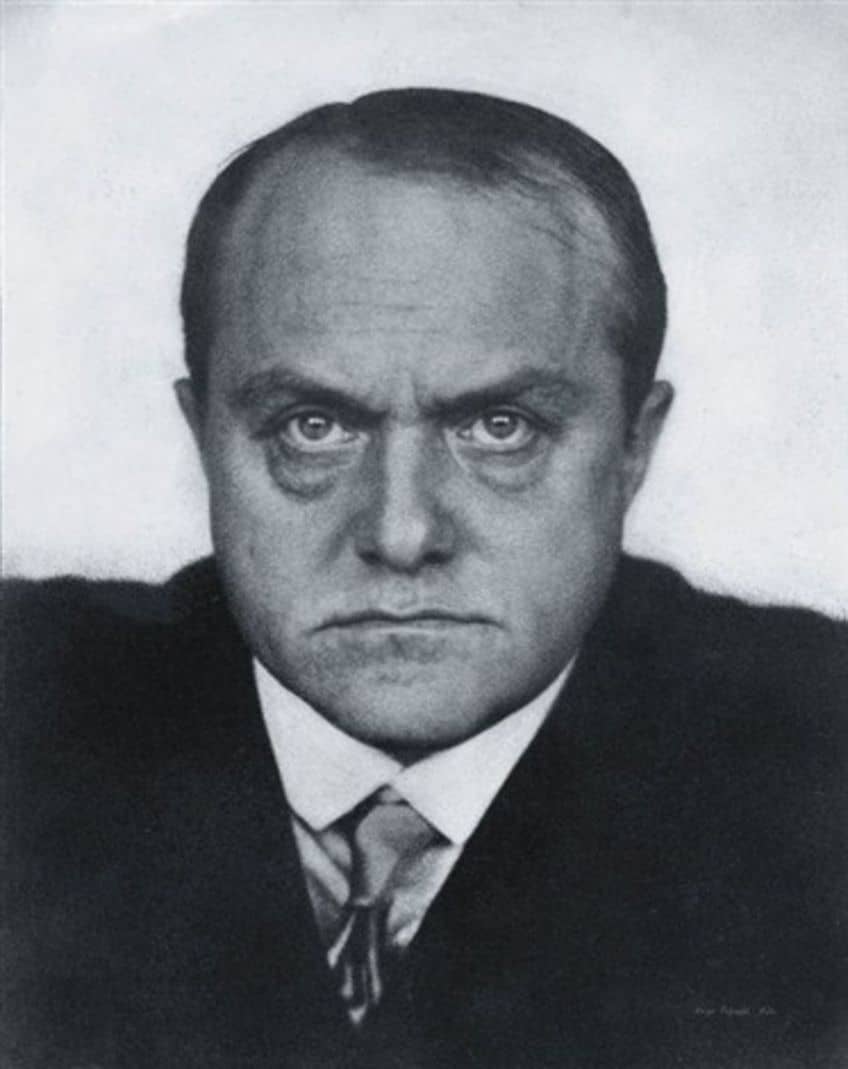

Max Beckmann, a pivotal figure in 20th-century art, left an indelible mark through his compelling and evocative works. Born in Leipzig, Germany, in 1884, Beckmann’s artistic journey traversed the turbulent landscapes of two World Wars and the interwar period, during which he became a luminary of the Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity movement.

Beckmann’s art is a profound reflection of the chaos and disillusionment of his era. His experiences as a medic in World War I profoundly influenced his work, leading to a body of art that starkly portrayed the human condition with a sense of raw emotion and haunting intensity. His paintings, such as the Self-Portrait with Horn (1938) series, reveal his mastery of conveying psychological depth through powerful symbolism and expressionist techniques.

Beyond war-related themes, Beckmann’s oeuvre delved into the complexities of urban life and society, often exploring themes of isolation, alienation, and existential angst. His use of bold lines, sharp contrasts, and a rich color palette imbued his works with a striking sense of urgency and emotional resonance. Despite the turbulence of his time, Max Beckmann’s artistic legacy endures as a testament to the power of art to probe the human psyche and explore the complexities of life.

His enduring impact continues to captivate and inspire, reminding us of art’s capacity to transcend temporal boundaries and illuminate the human experience.

Otto Dix (1891 – 1969)

| Date of Birth | 2 December 1891 |

| Date of Death | 25 July 1969 |

| Place of Birth | Untermhaus, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Periods | Expressionism, Modern art, New Objectivity, and Dadaism |

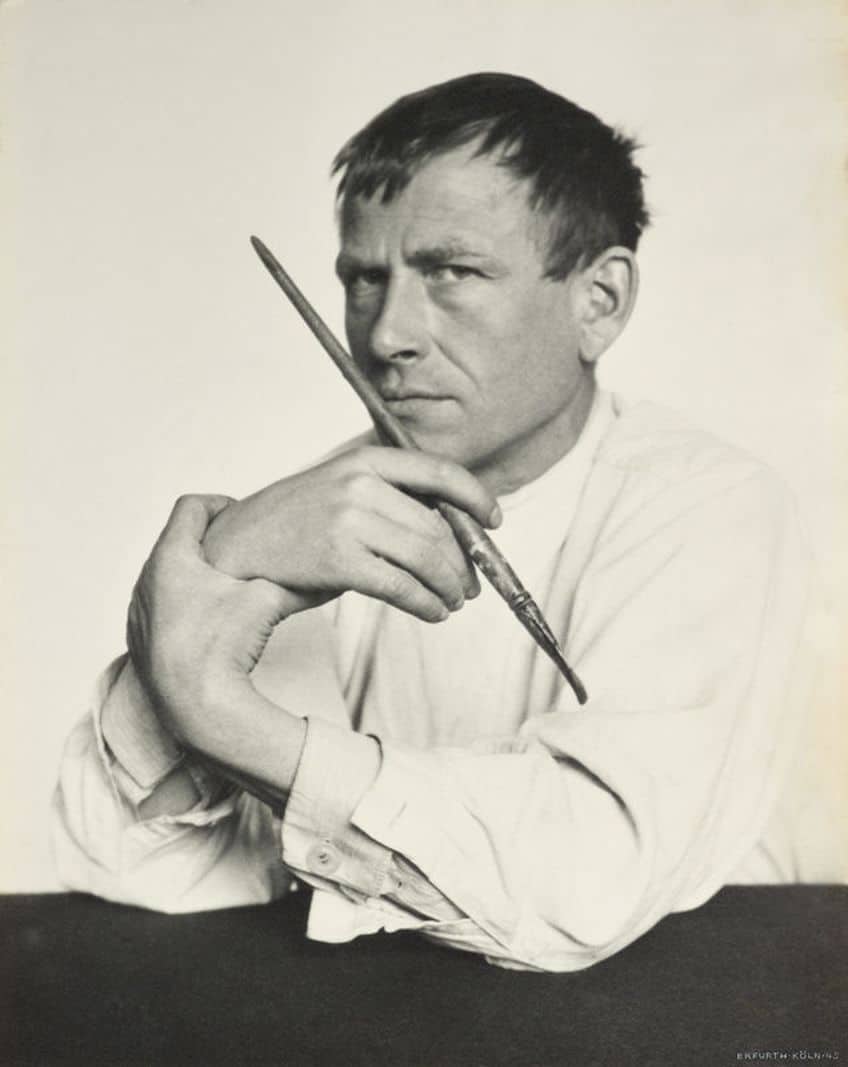

Otto Dix, a prominent 20th-century German artist, challenged societal norms and conventions with unflinching intensity. His art, deeply influenced by his experiences as a soldier in World War I, starkly portrayed the horrors of conflict.

Beyond war depictions, he exposed the decadence and moral decay of Weimar Republic society through satirical works, particularly in his portraits of marginalized individuals. Dix’s mastery of technique, precise draftsmanship, and skilled use of light and shadow imbued his art with striking realism and psychological depth. Despite its provocative and controversial nature, Dix’s art serves as a powerful testament to the artist’s role in critiquing society. His enduring impact continues to inspire contemplation, highlighting art’s ability to confront uncomfortable truths.

Dix’s legacy underscores the enduring power of artistic expression.

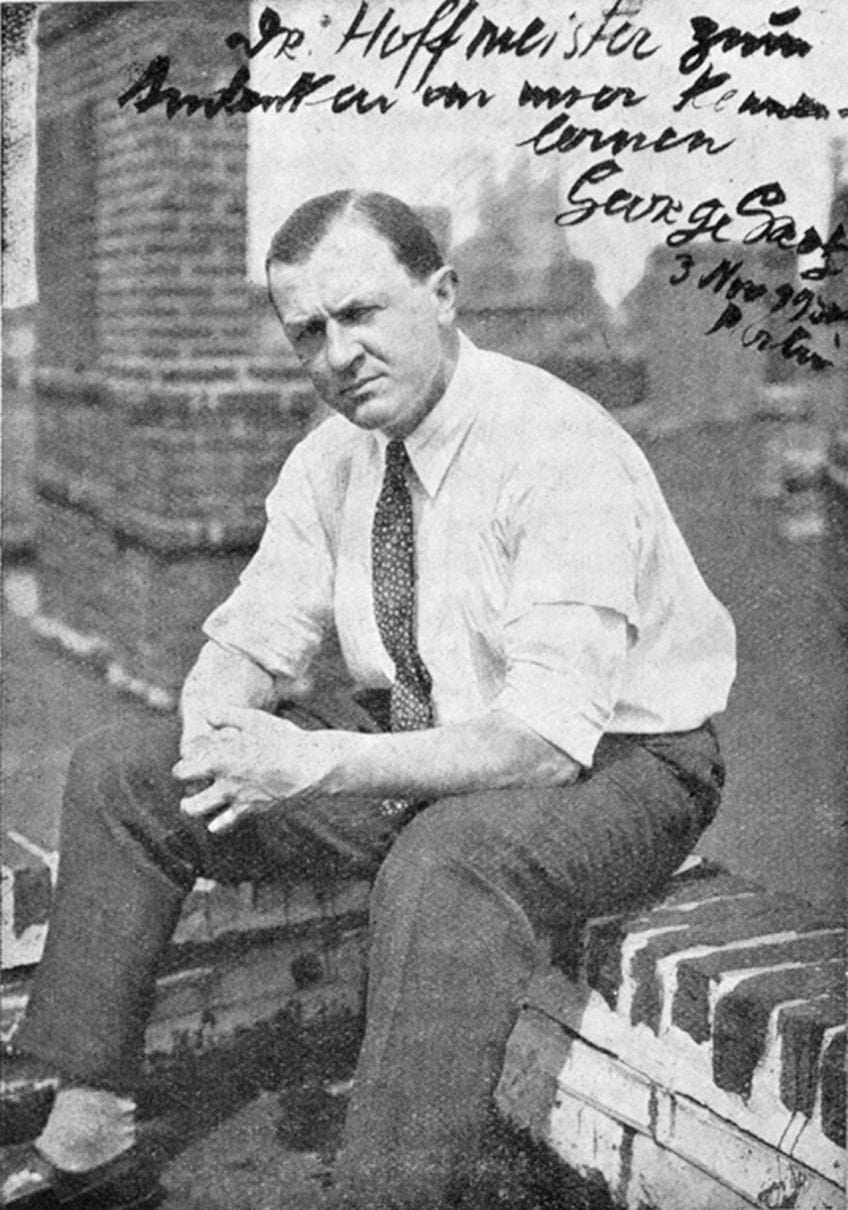

George Grosz (1893 – 1959)

| Date of Birth | 26 July 1893 |

| Date of Death | 6 July 1959 |

| Place of Birth | Berlin, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Periods | Expressionism, Modern art, New Objectivity, and Dadaism |

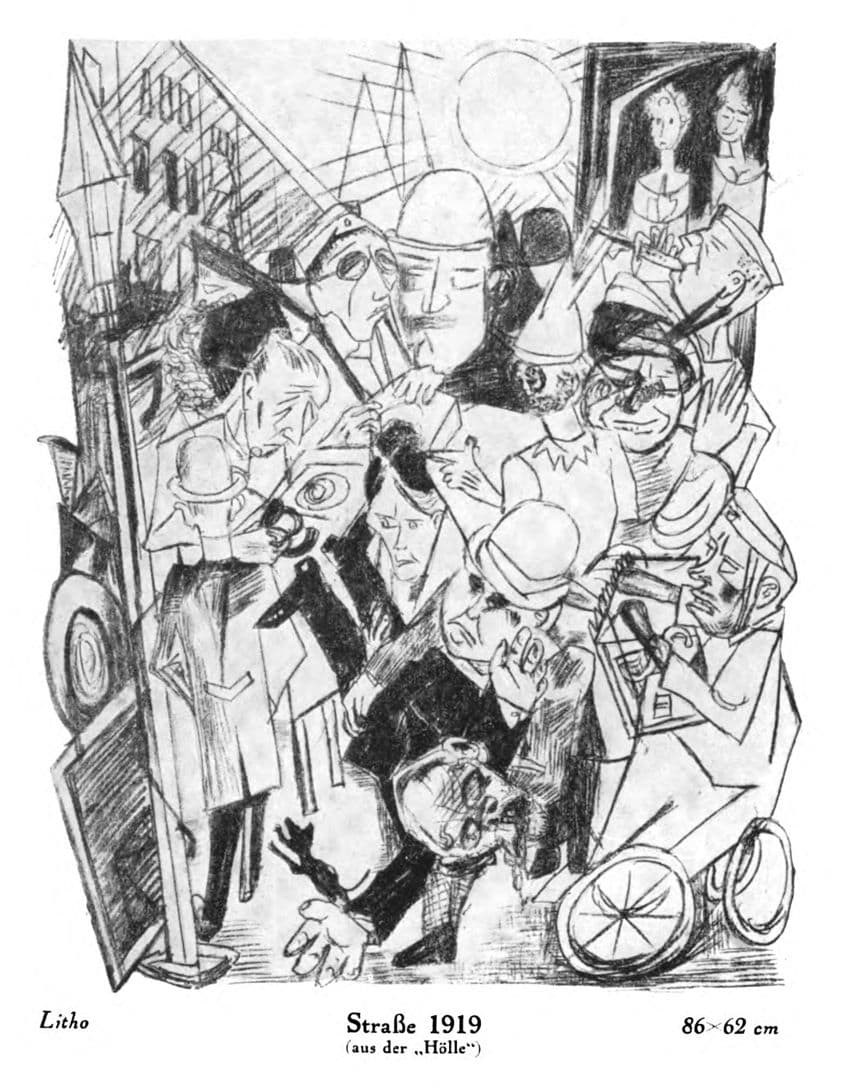

George Grosz, an important figure in 20th-century art, was a Berlin-born artist known for his unapologetic exposition of the Weimar Republic’s societal and political decay. He employed biting satire and sharp irony in his art, creating caricatures and illustrations that exposed the era’s excesses and hypocrisies.

Grosz also delved into multimedia, using collage and assemblage techniques to offer a dynamic and innovative approach to his work. His distinctive style featured angular lines, distorted forms, and grotesque exaggerations to confront complacency and reveal uncomfortable truths. Throughout his career, Grosz remained a vocal advocate for social justice and a critic of authoritarianism, leaving a lasting influence on art and social commentary.

His legacy reminds us of art’s power to challenge conventions and expose the underlying truths of society.

Famous German New Objectivity Paintings

Within the New Objectivity movement lie a myriad of iconic paintings that have left an unforgettable mark on the art world. In this section, we embark on a visual journey through some of the most famous German New Objectivity paintings, each a masterful testament to the movement’s commitment to depicting the blunt and often unsettling realities of the interwar period. These artworks not only reflect the technical virtuosity of their creators but also serve as windows into the complex and ever-evolving socio-political landscape of the time.

The Night (1919) by Max Beckmann

| Title | The Night |

| Date | 1919 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 133 × 153 |

| Location | Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany |

Max Beckmann’s The Night, painted in 1919, is a powerful and haunting work of art that epitomizes the artist’s mastery of the Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, movement. The painting is a large painting filled with intricate details, vivid symbolism, and multiple figures.

In the center panel, we are confronted with a chaotic and disorienting scene. A male figure, presumably Beckmann himself, lies on a bed, his face contorted in anguish. It is unclear whether he is being tortured or attended to by a doctor. Surrounding him are grotesque, distorted figures that seem to emerge from the darkness. The use of angular lines and harsh contrasts of light and shadow heightens the sense of turmoil and psychological tension.

The bed itself appears to morph into a coffin-like structure, suggesting a sense of entrapment or impending doom.

To the right, on the floor, a woman with a partially exposed backside hangs from a pole or is bound by the hands. Her presence is ambiguous, and her role in the narrative remains open to interpretation. She may represent a muse, a prostitute, or sinister sexual forces, adding an element of mystery to the composition.

The Night is a profound exploration of the human psyche and the existential anxieties of the post-World War I era. Beckmann’s use of grotesque, nightmarish imagery reflects the trauma and disillusionment experienced by a generation that had witnessed the horrors of war and the disintegration of societal norms.

The compositional format suggests a narrative structure, inviting viewers to contemplate the interconnectedness of the scenes. The central figure, with its tormented expression, can be seen as a representation of the artist’s inner turmoil and the collective trauma of the time. The surrounding figures, with their surreal and surrealistic elements, provide a broader commentary on the chaotic and disorienting nature of post-war society.

The Skat Players (1920) by Otto Dix

| Title | The Skat Players |

| Date | 1920 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas with photomontage and collage |

| Dimensions (cm) | 110 x 87 |

| Location | Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, Germany |

Otto Dix’s The Skat Players depicts three disfigured war veterans engaged in a game of Skat, a popular card game in Germany. The composition is strikingly symmetrical, with the three figures seated around a table, each engrossed in the game. Their uniforms, covered in military medals and decorations, serve as a poignant reminder of their past service and sacrifice. The men’s expressions are impassive, almost detached, as they focus on their cards. Their disfigured faces and amputated limbs are rendered in unapologetic detail, a testament to the physical and psychological scars of war.

The lighting in the room is harsh and unforgiving, casting shadows that accentuate their injuries.

Dix’s meticulous attention to detail extends to the cards themselves, adding an element of irony and symbolism. The Skat cards held by the players feature war motifs, further emphasizing the inescapable presence of the war in their lives.

The Skat Players is a poignant exploration of the physical and psychological toll of war on individuals and society. Dix’s unflinching realism forces viewers to confront the harsh realities faced by war veterans, whose lives were forever altered by their service. The symmetry of the composition highlights the uniformity of their suffering, underscoring the collective trauma experienced by a generation.

The use of the Skat game as a backdrop is significant. It symbolizes the mundane and even frivolous aspects of life that persist in the face of profound trauma. The players’ stoic expressions suggest a sense of resignation and numbness, as they grapple with the futility of their situation.

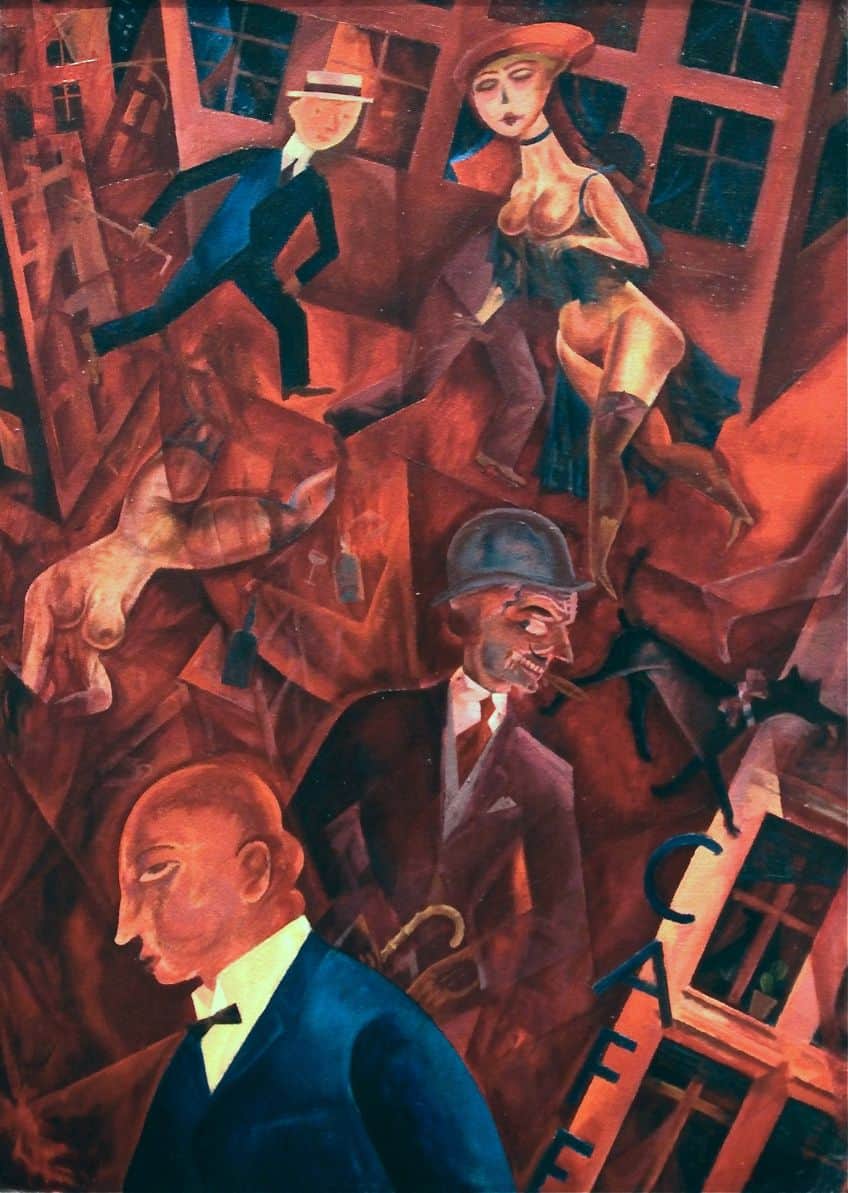

Eclipse of the Sun (1926) by George Grosz

| Title | Eclipse of the Sun |

| Date | 1926 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 207.3 × 182.6 |

| Location | Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, United States |

In Eclipse of the Sun (1926) by George Grosz, we are confronted with a searing depiction of the social and political turmoil of Weimar Republic Germany. Grosz employs sharp and biting satire to lay bare the corruption and moral decay of the era.

The composition is a cacophony of grotesque and exaggerated figures, each a caricature of the societal elites and power brokers. Two of the figures’ faces are contorted into masks of greed, lust, and deceit, their exaggerated features reflecting the artist’s contempt for the moral bankruptcy of the time. The rest of the figures around the table are illustrated as mindless bureaucrats by Grosz literally painting them without heads.

These figures, dressed in elegant attire, engage in debauchery and excess, surrounded by symbols of Germany’s political, military, and industrial sectors.

Grosz’s use of sharp lines and harsh contrasts intensifies the sense of moral ugliness, and the angular forms of the figures create a nightmarish and chaotic atmosphere. The very structure of the composition, with its distorted perspective and disjointed elements, mirrors the disintegration of societal norms during this tumultuous period.

In Eclipse of the Sun Grosz uses art as a weapon of social commentary – he unveils the dark underbelly of an era marked by excess and moral insolvency. The exaggerated, grotesque figures represent the moral degradation of the ruling class and their exploitation of the masses.

The title, Eclipse of the Sun, suggests the overshadowing of morality and justice by the forces of greed and immorality. It symbolizes the eclipse of reason and decency in a society that had lost its way. Grosz’s unflinching portrayal of this bleak reality challenges viewers to confront the uncomfortable truths of their time. Through Eclipse of the Sun, George Grosz invites us to reflect on the consequences of unchecked power, greed, and moral decay. His mastery of satire and visual distortion makes a powerful statement about the human condition and the societal forces that shape it.

In conclusion, German New Objectivity, or Neue Sachlichkeit movement, stands as a compelling chapter in the annals of 20th-century art. It emerged as an assertive response to the rough socio-political climate of post-World War I Germany. Artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann masterfully employed unflinching realism, biting satire, and profound symbolism to confront the harsh realities of their time. Through their works, they challenged societal norms and laid bare the moral decay and corruption of the Weimar Republic. The legacy of New Objectivity movement persists, reminding us of the enduring power of art to confront uncomfortable truths and transcend the boundaries of convention.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is New Objectivity in Art History?

The New Objectivity, or Neue Sachlichkeit in German, refers to an influential art movement that emerged in the aftermath of World War I, primarily in Germany. This movement, active during the 1920s and early 1930s, was characterized by a sharp departure from the expressive and abstract tendencies of previous art movements. Instead, artists of the New Objectivity aimed to depict the world with precise and unapologetic realism. They portrayed everyday life, often emphasizing the harsh and unvarnished realities of their time, including the societal upheaval, moral decay, and political unrest of post-war Germany.

What Are the Characteristics of the New Objectivity Art Movement?

The New Objectivity art movement, or Neue Sachlichkeit in German, is characterized by several distinct features. First and foremost is its commitment to precise and unflinching realism, portraying everyday life with sharp detail and accuracy. Artists of this movement often depicted the stark and often unsettling realities of their time, including the aftermath of World War I, societal decay, and political unrest. The New Objectivity artists employed a range of techniques, including precise draftsmanship, bold lines, and stark contrasts of light and shadow. They embraced satire and caricature to critique the moral and social issues of their era. This movement challenged the romanticism and idealism of previous art styles, offering a stark and truthful portrayal of the world, ultimately emphasizing the power of art to confront uncomfortable truths and provoke contemplation.

What Is New Objectivity in Architecture?

New Objectivity in architecture is a movement that emerged in the early 20th century, primarily in Germany. Similar to its artistic counterpart, New Objectivity in architecture rejected the ornate and extravagant designs of the previous era, favoring a straightforward and functional approach instead. This movement emphasized clean lines, simple geometric shapes, and a focus on the functional aspects of buildings. Architects aimed to design structures that were efficient, rational, and devoid of unnecessary ornamentation. This style is often associated with the Bauhaus school and the works of architects like Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. New Objectivity in architecture left a lasting influence, shaping the modernist architectural principles that would dominate much of the 20th century.

Can Art Be Objective?

The question of whether art can be objective is a complex and debated topic in the art world. Art is inherently subjective, as it reflects the personal experiences, emotions, and perspectives of the artist. However, some argue that certain aspects of art, such as technique, composition, and craftsmanship, can be evaluated objectively. Additionally, art can strive for objectivity by representing the world with a high degree of realism and precision, as seen in movements like the New Objectivity. Yet, even in such cases, interpretation and emotional response remain subjective elements of the art experience. Ultimately, while objective criteria can be applied to elements of art, the overall impact and meaning of a work often depend on the viewer’s subjective perception and context.

Nicolene Burger, a South African multimedia artist and creative consultant, specializes in oil painting and performance art. She earned her BA in Visual Arts from Stellenbosch University in 2017. Nicolene’s artistic journey includes exhibitions in South Korea, participation in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, and solo exhibitions. She is currently pursuing a practice-based master’s degree in theater and performance. Nicolene focuses on fostering sustainable creative practices and offers coaching sessions for fellow artists, emphasizing the profound communicative power of art for healing and connection. Nicolene writes blog posts on art history for artfilemagazine with a focus on famous artists and contemporary art.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and about us.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, “New Objectivity Art – A Return to Detached Realism in Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 19, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/new-objectivity-art/

Burger, N. (2023, 19 September). New Objectivity Art – A Return to Detached Realism in Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/new-objectivity-art/

Burger, Nicolene. “New Objectivity Art – A Return to Detached Realism in Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 19, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/new-objectivity-art/.