Readymade Art – The History and Legacy of Readymade Art

What is Readymade art and what are the most notable Readymade art examples? Marcel Duchamp, the French artist, was the first person to use the term to characterize the artworks he produced using pre-manufactured objects. Since then, it has commonly been used more extensively to refer to artworks created in this manner by various Readymade artists. One of the first Readymade art examples was Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913), a Readymade sculpture that comprised a wheel of a bike mounted on a stool made of wood.

Putting Together the Pieces of Readymade Art

Many artists felt alienated by a civilization that could partake in such horrors as World War I, so they wanted to break free from established or traditional methods of making art, searching for new ways to innovate by probing into every area of their society and encouraging fresh ideas. The “readymade”, a genre in which artists picked commonly found items from ordinary life and repurposed them as art pieces such that their original value vanished in light of stimulating fresh perspectives, arose from this flood of defiant re-investigation. This shifted society’s perception of what art should or could be, injecting a spontaneous, new context into a stale old visual language. It also opened the way for Conceptual art, which focused on conveying ideas and the process of investigating them instead of a completed art piece.

History of Readymade Art

Today, the Readymade is a widespread genre in art, as prevalent as painting and other more established materials in artists’ oeuvres. In today’s culture, artists continue to investigate everyday things, raising them to the level of art as a tool for questioning society’s connection with the planet, commercialization, mass production, and our relationship with the physical world of our own manifestations.

Let’s take a look at how Readymade art emerged onto the art scene.

The Dada Influence

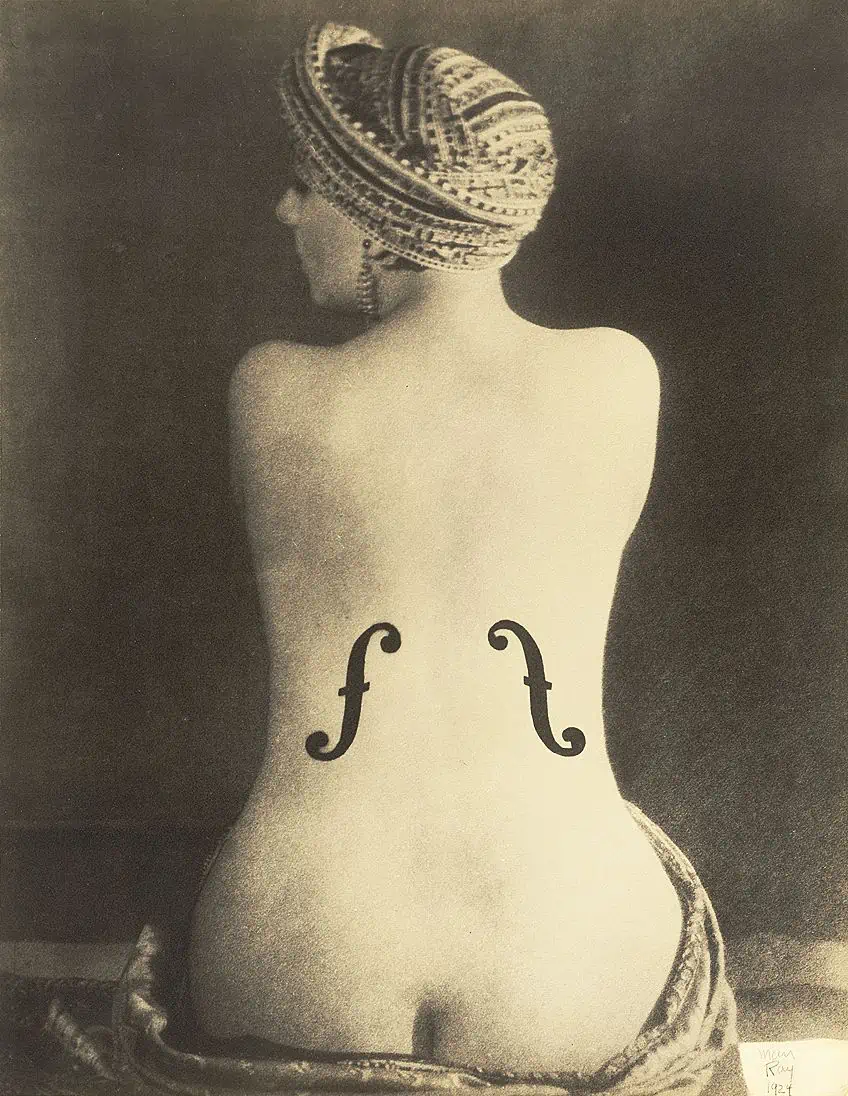

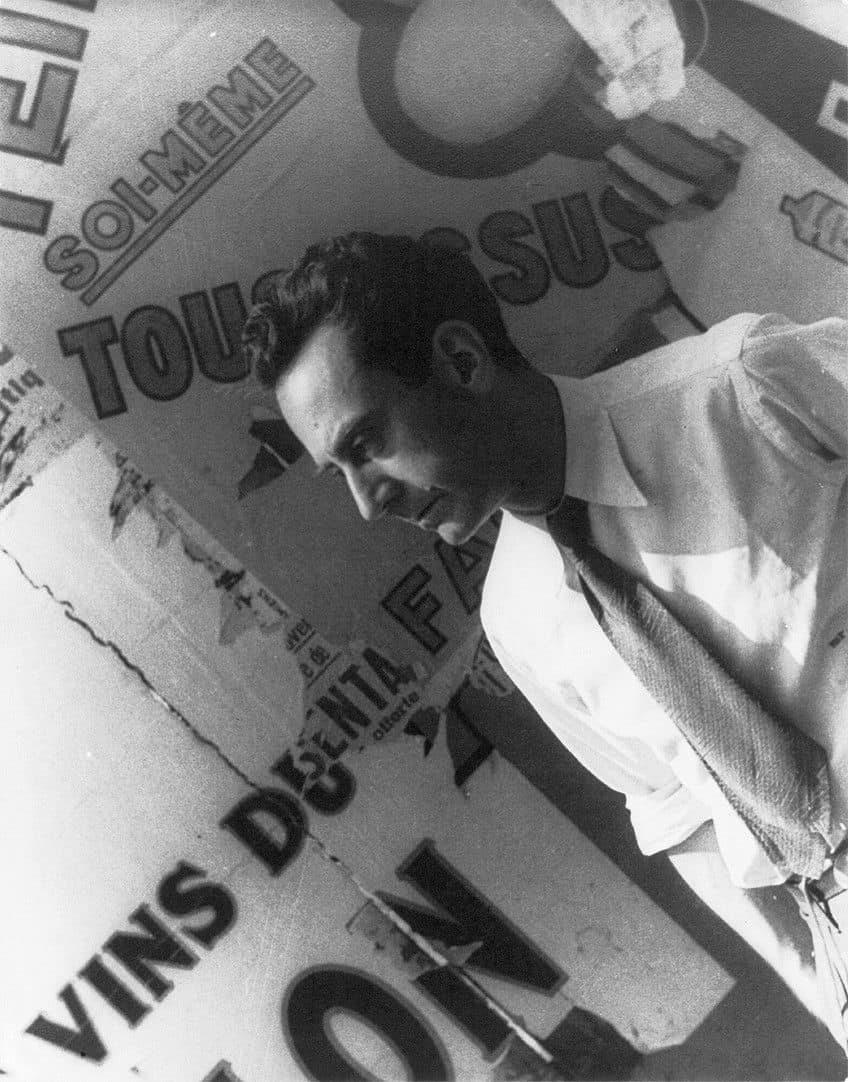

Following the atrocities of World War I, many creative types and intellectuals began to scrutinize every facet of their civilization that had enabled it to happen. Artists began to consider how technologies, commerce, creativity, and politics were all interconnected. The origins of Dada were not the foundations of art, but of revulsion”, wrote Tristan Tzara, the French-Romanian poet. Hugo Ball, Tzara, Hannah Höch, Man Ray, and Max Ernst, among others, determined that the only way to react to these insights was to create irreverent and even absurd artworks.

Dada artists created new visual languages that aspired to exist beyond the strict structures of current society using methods such as assemblage, collage, and photomontage. The name Dada, although disputed in origin, is supposed to derive from the Romanian phrase “Yes, yes” and the French phrase “rocking horse”, illustrating its global beginnings. The Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, Switzerland, was a popular hangout for Dada artists at the time, but the movement quickly expanded to Paris and then subsequently to New York.

Found Objects

The term “found object” is a straight translation of the French objets trouvés, which refers to common things that have been integrated into an artistic environment and so converted from non-art to artwork. Although these found objects were connected with the art world prior to the 1900s, they were mainly featured as parts of larger collections, for example in Victorian curiosity cabinets. It would not be until the early 20th century that artists began using them in their works. When he utilized the backrest of a chair as an element of his Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), Pablo Picasso is largely regarded as having created the first work of art to integrate found materials. The artwork was also regarded as one of the first examples of Synthetic Cubism.

Picasso started to tear down the barriers between real life and art by adding these materials into his works, illustrating that art is always derived from real life.

The Influence of Marcel Duchamp

It was Marcel Duchamp, the French American artist who elevated the found object to greater levels in his readymade art concept. Though Duchamp is often regarded as the originator of the readymade, the phrase was previously in use considerably earlier to refer to things created by industrial methods. He began painting in 1904 and attended the Academie Julien in Paris from 1904 to 1905. His earlier works exhibit Cubist influences and look ahead to Futurist works: his Nude Descending the Staircase (1912), for instance, aimed to represent the figure in motion, implying the static and dynamic through fractured lines. Within the very same year, however, Duchamp started to abandon painting, dismissing what he called “retinal art”.

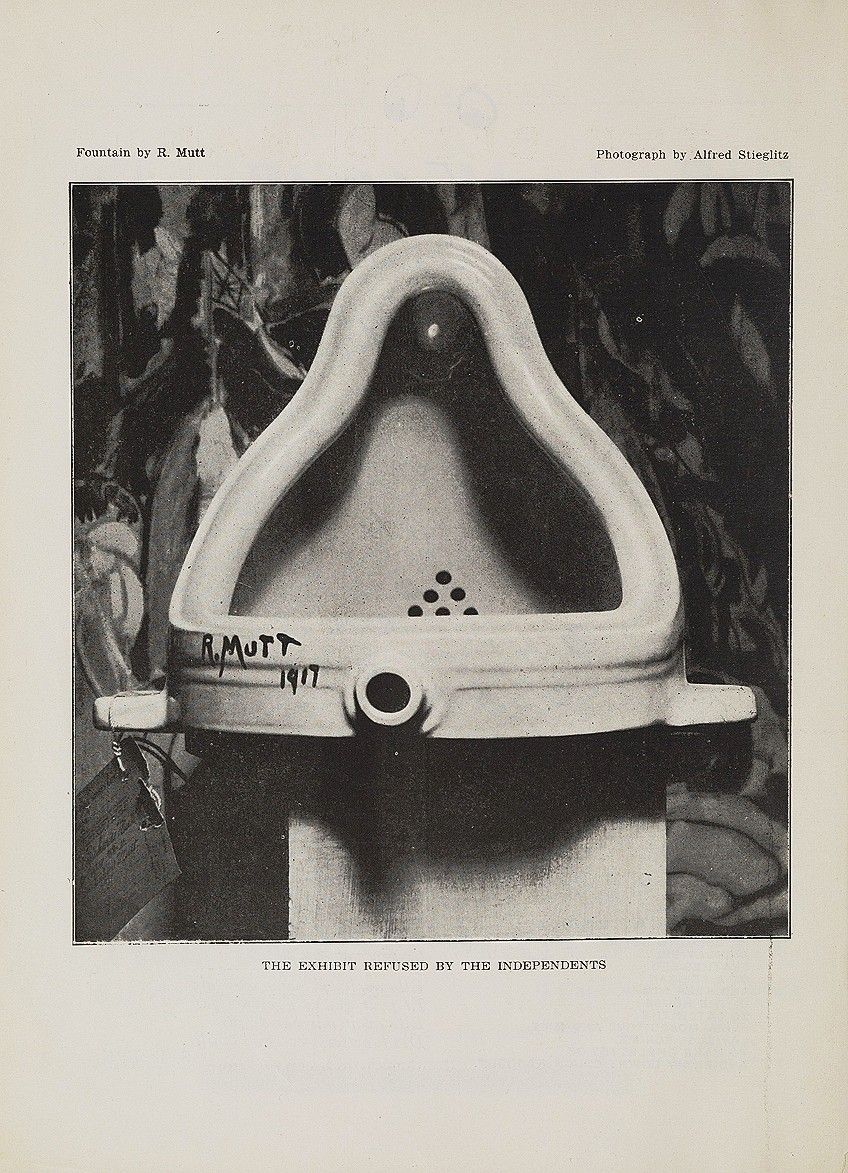

He began exploring the notion of Readymade art when one day in his workshop, he set a bike wheel on a stool, and from there he played with numerous shapes, including things he picked on their own or altered or transformed in some tiny manner. For Duchamp, readymade art is in direct dialogue with manufacturing and industry by elevating mass-produced things by placing them in new surroundings and identifying them as artworks, he examines the mechanism by which anything becomes regarded as art in the first place. In 1917, using the alias “R. Mutt”, Duchamp presented Fountain, a simple urinal, to the Society of Independent Artists for their display of modern artworks. Duchamp was a fellow of the Society’s Board of Directors, and the Readymade sculpture sparked heated controversy among its members concerning its legitimacy as art.

It was rejected during an emergency meeting, and it was hidden from public view in the exhibit.

Duchamp was enraged by this choice and, the next month used a pseudonym to justify the piece in The Blind Man, the journal he co-edited. He stated: “It makes no difference whether Mr. Mutt built the urinal with his hands or not. He selected the piece. He took an everyday thing, rearranged it such that its usefulness vanished under the new name and perspective – and generated a new concept for that object”. Jonathan Jones sees a new point of departure for art in the 20th century in this comment, saying, “It’s as though modern art history starts with him”.

The Hidden Influence of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Though Marcel Duchamp is often regarded as the inventor of readymade sculpture and art, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhove, the artist from Germany, is now regarded as an equal innovator. Loringhoven went across Europe, hanging out with bohemian artists, and worked as a waiter, performance artist, chorus girl, and eventually, a model for photographers. However, it was in the States that she started to grow as an artist. She married Baron Leo von Freytag-Loringhoven in New York, earning her the moniker “The Baroness”.

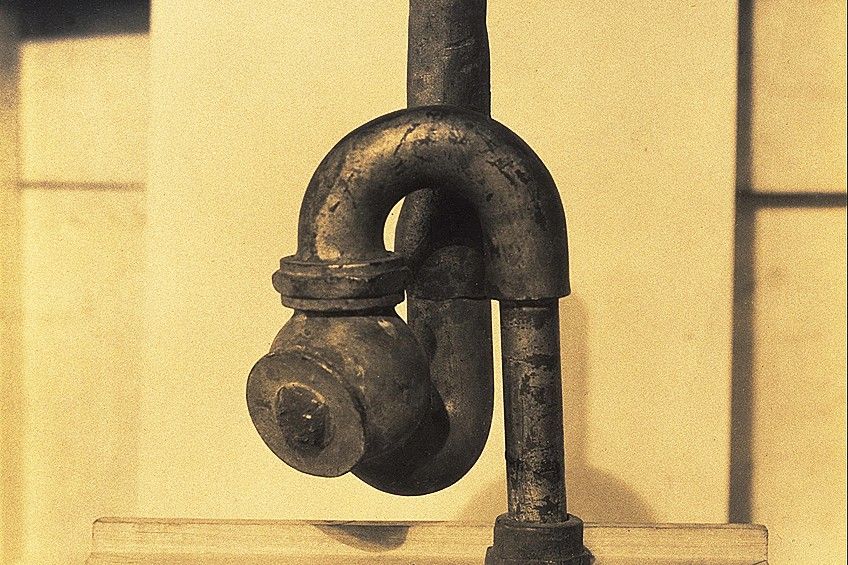

In 1913, she created her first artwork with a found object, a corroded metal ring, and the piece was titled Enduring Ornament. In the same year as The Fountain was produced, the Baroness created additional pieces, notably God, a collaborative work with Morton Livingston Schamberg. Readymadart became a tool for challenging society’s expectations and standards through these prominent personalities, giving a means of examining the commercialization of aesthetics.

Readymade Sculpture and Surrealism

Duchamp’s works had a huge impact on art practice and theory and he impacted many of his friends and associates. André Breton, a Surrealist enthusiast, used and spoke about readymade sculpture as a way to disturb consciousness and stimulate the unconscious. In comparison to Duchamp, Breton investigated society’s obsession with and identification with objects in an article titled The Crisis of the Object in 1937. He aimed to examine how humans engaged with things in general, and how new connections could be produced using techniques like alienation or assemblage. The contrast between a lobster and a telephone in Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone (1936) was intended to disclose latent connections and impulses.

The arrangement appeared to recall the lexicon of dreams, in which fresh combinations of things and thoughts become ordinary, as well as being humorous and intriguing.

Later Developments

The readymade was frequently utilized by artists whose works interacted with postmodernism and aimed to challenge mass culture production in the late 20th century. Numerous young artists in America adopted Duchamp’s concepts and ideals. Robert Rauschenberg, especially, was heavily inspired by Dadaism and frequently used found materials in his collages to blur the line between low and high culture. With the addition of a tire, his First Landing Jump (1961) put a twist on Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel while also referring to the car-obsessed society of 1960s Americana.

He and others were known as Neo-Dadaists as a result of their use of comedy, play, and criticism of pop culture and aesthetic judgment. Other Neo-Dadaists, such as Jasper Johns and Joseph Beuys, responded to Duchamp’s theories with work that disturbed or questioned the link between art objects and exhibition space. Flashlight and Lightbulbs (both 1958) by Jasper Johns allude to Duchamp’s disruptive goals while also going back to creative craft and technique. Johns purchased both artifacts and fashioned them into a metal foundation. The works evolved into composite Readymade sculptures, complicating the concepts of production, taste, and uniqueness even more.

Readymade art would create the essential groundwork for Conceptual Art by allowing artists to explore and enhance the representation of a concept as a piece of art in and of itself. They would also impact current artists, most notably in the 1960s Pop Art movement, which took common imagery from pop culture and raised them into the canon of artwork.

The Young British Artists

The Readymade took on fresh life in the late 1980s and early 1990s thanks to a collection of artists called the Young British Artists. These young artists, including Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, and Rachel Whiteread, were known for their unsettling work that sold for exorbitant sums. They also frequently made references to mass-produced goods and products from popular culture or ordinary objects and experimented with putting them in unexpected situations and arrangements.

They were motivated by Duchamp’s concepts of “choice” and “preference”, according to which an item only becomes art if the artist chose it as such. Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), which was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1999, is possibly the most well-known Readymade from this era. People were critical of Emin’s work (her real bed and the clutter around it) because they believed it was sloppy and lacked creative flair. Emin objected to accusations that anybody could make this work, saying, “Did they, or didn’t they? The point is that it had never been done before”.

Readymade Art Styles and Concepts

The main precepts of the Dada readymade ideology were to select an object, the very which was regarded as an artistic endeavor itself; nullify that object’s recognizable function by displaying it as a work of “art” rather than its usual function, and give it a title that possibly prompted a new way of thinking or significance. Although readymades were unmistakable representations of everyday things, they were frequently changed, rearranged, or merged into assemblages to demand greater ambiguity, further distancing them from any predetermined interpretation. An artist became a “selector” rather than a “creator” in the Readymade light.

This established the framework for art to exist as a medium that could represent thoughts, processes, and concepts rather than just visual displays.

Originality

One of the most problematic difficulties readymade artists face when repurposing existing things into new creative settings is the issue of originality. What exactly is an original work of art? How much effort must an artist put into a piece for us to declare it is a one-of-a-kind piece of art? Can an artist genuinely claim ownership of a piece of art if it existed before he or she appropriated the object? These are only a few of the questions that readymade art raises. On a daily basis, they ask questions about our associations with familiar items. By putting things in an artistic framework, we are occasionally made to realize how much we consider to be routine in front of our eyes every day.

For certain critics, the concept of readymade art in and of itself is contentious because original pieces that have been lost, destroyed, or worn out by time are occasionally reproduced by the artists themselves or by institutions. Duchamp’s first readymade, Bicycle Wheel (1913), for instance, has been replicated three times, while the original versions of many others have been lost entirely. These Readymade sculptures, however, raise even more significant problems regarding originality in their reimagining: can we still declare that this is the identical artwork that was first displayed? What effect does it have on the worth of art if we can merely recreate a lost work?

Use of Visual Humor and Puns

Themes of humor and wordplay were common in Readymades, and Readymade artists frequently incorporated visual puns into their works. Duchamp’s art, like Dadaism’s, aims to undermine conventional standards and experiment with meaning and significance. L.H.O.O.Q (1919) blends a visual and linguistic pun: when pronounced loudly in French, the title sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul”, which translates as “she has a cute butt”, and the picture displays a goatee and mustache, pencil-drawn over a replica of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503).

The piece is a whimsical twist on one of the Renaissance’s most respected works, and it articulates a new creative ambition to unearth new meanings from old artworks, whether they are daily items or works of great significance.

Taste and Aesthetics

Readymades also challenge the concept of aesthetic preferences and choice. We have typically seen art in the setting of a gallery as a consumable thing that can be purchased and exhibited. Readymades question the notion of art as ornamental by including or employing things that are not immediately recognized as attractive. In this way, Readymade art indicates that a piece of art is more than just an aesthetic item. Duchamp proposed that in order to produce a Readymade, one must have “ambivalent taste”, that is, the ability to set aside one’s conventional standards for beauty and connect with the item in a fundamentally unexpected way.

Mass Production

Duchamp and other designers studied the link between technology and art and industry while selecting mass-produced products. The 20th century saw a major transformation in the way goods were created due to growing automation and the global spread of factories. Mass manufacturing leads people to think about products in terms of usefulness rather than beauty.

However, by using Readymade sculpture, artists may inspire their audiences to reconsider these products and appreciate them for their intrinsic appeal rather than their intended use.

Concepts

In that it broke down preconceptions, challenged originality, showed familiar associations as useless mental constructions, and addressed the commodity of beauty in general, Readymade art became a tool to challenge society’s norms. Aesthetics, taste, and mass manufacturing were all scrutinized, frequently with an irreverent or even humorous tone. The readymade called into question man’s connection with things in general. What commonplace items do we take for granted? What new connections could be formed when these things are transferred from a state of complacency to a state of fresh perspective? What effect may this have on normal thought and the unconscious?

The phrase “Readymade art” refers to art made from repurposed things. These items are frequently tweaked by the artist, who emphasizes the non-art character of the original piece while concealing its practical function. Readymade art questioned Western art standards by asking what sorts of items deserved to be designated as art as well as whether those pieces were fit for gallery exhibitions or museums. By doing so, they raised the question of what “real” art entails. The selection process, they believed, was in itself a creative process that deserved to be recognized. By choosing and altering the piece, they hoped to lift it from the realm of everyday life into something that could be regarded as high art. Readymade artists changed the way art is perceived and what can be considered art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Readymade Art?

Marcel Duchamp was said to be the first to use the term in order to describe everyday objects that had been transformed into art merely by their selection and placement. Surprisingly, the phrase used by Duchamp to define his new method of art creation is one that is readymade in and of itself. By the late 19th century, the phrase was then used to characterize products that were manufactured rather than handcrafted. Duchamp started making Readymade objects when he first took a bicycle wheel and placed it upon a stool.

What Is the Theory Behind Readymade Art?

There are three key aspects here: first, the selection of an item is a creative act in and of itself. Second, by removing an object’s useful purpose, it becomes an artwork. Third, the display of the item and the inclusion of a label have given it a new meaning. Readymades also established the concept that the artist defines what constitutes art. Choosing the thing is a creative act in and of itself; canceling away the functional purpose of the object transforms it into art, and its exhibition in galleries gives it new significance. This shift from artist-as-creator to artist-as-selector is frequently regarded as the start of the Conceptual art movement since the position of the designer and the object is brought into question. At the time, Readymade culture was perceived as an attack not just on the position of art, but also on its fundamental character.

Who Was the First Artist to Create Readymades?

Bicycle Wheel (1913) was one of Duchamp’s first readymades. In 1917, Duchamp created his most famous readymade, Fountain, a men’s urinal signed by the creator with a fictitious name and displayed on its back in New York. Later readymades were more intricate and were referred to as aided Readymades by Duchamp. Readymades include pieces by YBA artists Michael Landy, Damien Hirst, and Tracey Emin, among others. Marcel Duchamp is considered a pivotal player in the evolution of modern and contemporary art, and his oeuvre, which ranges from paintings to the plastic arts, has had a lasting influence.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Readymade Art – The History and Legacy of Readymade Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. March 6, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/readymade-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 6 March). Readymade Art – The History and Legacy of Readymade Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/readymade-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Readymade Art – The History and Legacy of Readymade Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, March 6, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/readymade-art/.