Conceptual Art – A Look at the Important Conceptualist Art Movement

What is Conceptual art? The Conceptualist artist emphasizes concepts above the formal or aesthetic aspects of artworks. The Conceptualist art movement was an amalgamation of many inclinations rather than a strictly bound ideology, and it manifested itself in many different ways, including performances, occurrences, and ephemera. Conceptual artists created works and publications from about 1965 to around 1975 that entirely defied conventional notions of art.

Contents

- 1 What Is Conceptual Art?

- 2 The History of the Conceptualist Art Movement

- 3 The Trends and Styles of Conceptual Art

- 4 The Legacy of Conceptual Art

- 5 Important Conceptual Artworks

- 5.1 Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) by Robert Rauschenberg

- 5.2 Grapefruit (1964) by Yoko Ono

- 5.3 One and Three Chairs (1965) by Joseph Kosuth

- 5.4 Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) by Ed Ruscha

- 5.5 Two Correlated Rotations (1969) by Dan Graham

- 5.6 MoMA Poll (1970) by Hans Haacke

- 5.7 Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, Financial Section (1971) by Marcel Broodthaers

- 5.8 The Vertical Earth Kilometer (1977) by Walter de Maria

- 5.9 Imponderabilia (1977) by Marina Abramović

- 6 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Conceptual Art?

By asserting that the representation of an artistic concept is sufficient to qualify as a piece of artwork, Conceptualism artists suggested that concerns about aesthetics, expressiveness, competence, and commercial viability were all irrelevant criteria by which art was often assessed. Conceptualist artists have effectively redefined the idea of artistic work to the point that their creations are universally regarded as works of art by investors, museum curators, and art critics.

This has made it immaterial whether one agrees with this immensely cerebral style of art or not.

A Conceptual Art Definition

Conceptual artists are conscious of the theoretical nature of all work. Many Conceptualism artists did this by minimizing the amount of material in their works to reinforce this; this practice has been described as the “dematerialization” of artworks.

The Conceptualist art movement was inspired by the minimalism movement’s ruthless simplicity. However, the conceptualists disagreed with minimalism’s acceptance of painting and sculpture norms as the cornerstones of artistic expression.

Conceptual paintings or installations do not have to resemble a traditional piece of art in the eyes of conceptualist artists.

The History of the Conceptualist Art Movement

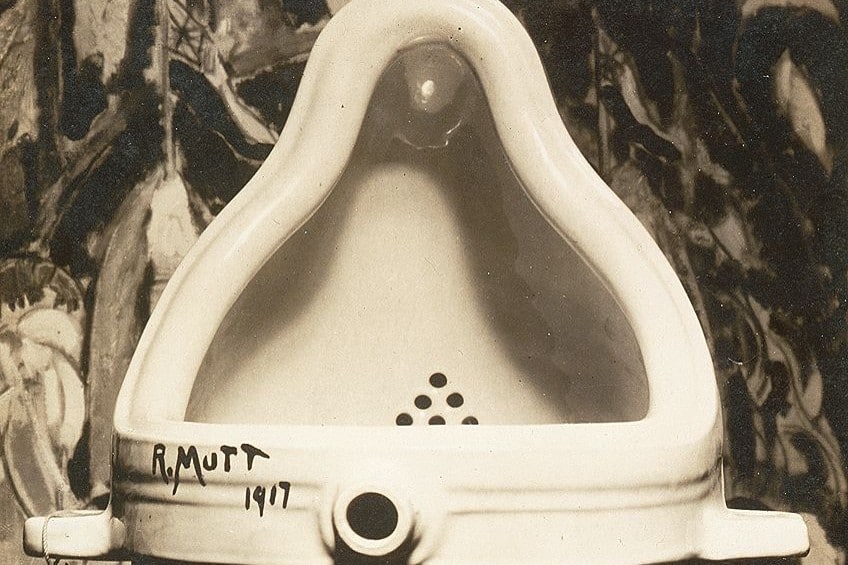

The works of Marcel Duchamp, who in the early 20th century formed the premise of the “readymade” – the found item that is purely selected by the artist to be a piece of artwork, with no adjustments to the object further than a signature – was one of the most significant precedents for Conceptualism art.

Fountain (1917), the first and most well-known real Readymade, was little more than a porcelain urinal that had been turned 90 degrees, set on a stand, dated, and signed.

Duchamp rejected the prevailing belief that works of art must exhibit creative competence by describing his Readymades as “anti-retinal”. Duchamp re-released Fountain for the Sidney Janis Gallery in the 1950s, many years after some of his original Readymades had been destroyed.

These activities sparked a resurgence of interest in idea-based art in the contemporary art world, as well as renewed interest in his work.

The Shift Towards Conceptual Art

Whereas the late 1950s saw a progressive transition in contemporary art from Abstract Expressionism to Pop and Neo-Dada, the late 1960s saw a similar change, but this occasion from Fluxus to Conceptualism art. Fluxus emerged in the early 1960s and shares many similarities with Dada.

Fluxus artists attempted to connect creativity and life by employing found items and noises, ordinary actions and events as stimulants, and embracing “flux,” or transition, as a fundamental aspect of existence.

Fluxus personalities such as Allan Kaprow, George Maciunas, and musician John Cage influenced Conceptualist artists. Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, as well as other Minimalist creatives who arose in the mid-1960s expanded modernist abstraction by emphasizing repetitions, formal simplicity, and industrial manufacturing of their works, contributing to Conceptual art’s broad ancestry.

Judd and others disregarded much that was customary in making works that filled space differently, frequently on a size too huge for a pedestal or residence, and were usually fashioned of atypical artistic materials such as sheets of steel or bricks that were outsourced. During this period, several emerging artists paid special attention to the paradigm shifts implicit in Minimalism and Fluxus, realizing that artwork was not reliant on the object itself, and might thus exist primarily as a concept.

Most considered their artworks as a direct rebuke to the art industry, which promotes artistic personalities.

The Influential Writings of LeWitt and Wiener

Sol LeWitt published his first book in 1967 Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, in which he stated, “What the piece of art looks like isn’t all that essential. If anything has physical form, it must appear to be something. Whatever shape it eventually takes, it must start with an idea. The artist is preoccupied with the processes of idea and manifestation.”

The idea of prioritizing concept above object, and the importance of realization over aesthetic considerations, directly challenged the concepts and works of formalist art critics such as Michael Fried and Clement Greenberg.

Their work – which was primarily concerned with the analysis of objects, materials, colors, and shapes – had contributed to the definition of the aesthetic requirements of the prior generation of painters. Lawrence Weiner took conceptual art to its logical conclusion in his 1968 “Declaration of Intent,” declaring that he would discontinue the procedure of constructing art, referencing no need to construct something when the concept behind any piece of artwork should serve its purpose because the artist’s intension persists the same, irrespective as to whether the artwork is in a material form or solely theoretical.

The Formation of the Conceptualist Art Movement

While conceptual artists remained a diverse, transnational group with a wide range of ideas about current art, it was clear by the late 1960s that an informal group was forming. In 1968, the trader and curator Seth Siegelaub held a series of Conceptual art exhibits in New York that strongly pushed the trend.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York assembled a group of artists from the Conceptualist art movement for an exhibit named Information in 1969.

This event was not taken lightly at all, because Conceptualism was generally skeptical of the institutionalized museum structure and its heavy market-driven goals, which was the entire framework within which they displayed their works.

The Emergence of Collectives

While lecturing art in Coventry, a group of British artists called themselves Art & Language in 1967. The group expressed an open dislike for the connection between modern artwork and the market in several journal articles.

Many would join the organization over the following few years, and its revolving membership would reach about 50 musicians until diminishing in the late 1970s.

Several artist collectives have a similar political persuasion. The Canadian collective General Idea consisted of three artists, Jorge Zontal, Felix Partz, and AA Bronson, who were interested in transitory works and installations. Their works tackled the pharmaceutical business and the AIDS problem in the 1980s when they were active from 1967 until 1994.

Conceptualism proved to be a successful avenue to creative and political resistance in South America. Conceptualism art was especially alluring since it was not an imported aesthetic in and of itself, but rather a mode of communication with no singular point of reference, whether cultural, artistic, or ideological.

Anonymity, and hence immunity from prosecution by repressive regimes, was afforded by artist collectives, as was the ability to make forceful social remarks.

The Trends and Styles of Conceptual Art

Because Conceptualism art was designed as a movement that stretched conventional limits, it can be difficult to identify self-conscious Conceptualist art from the numerous other trends in 1960s art. Conceptualism was not restricted to Conceptual paintings, but could also come in the form of occurrences, public performances, installations, body painting, and earth art.

The denial of traditional methods of appraising pieces of art, resistance to art as a product, and conviction in the fundamentally conceptual character of all artworks linked these trends.

Because it avoided aesthetics, conceptual work is impossible to characterize stylistically other than a presentation that appears impersonal and unemotional. While a conceptual piece may lack a distinct style, one could argue that its daily look and range of expression are hallmarks of the movement.

Art as a Concept

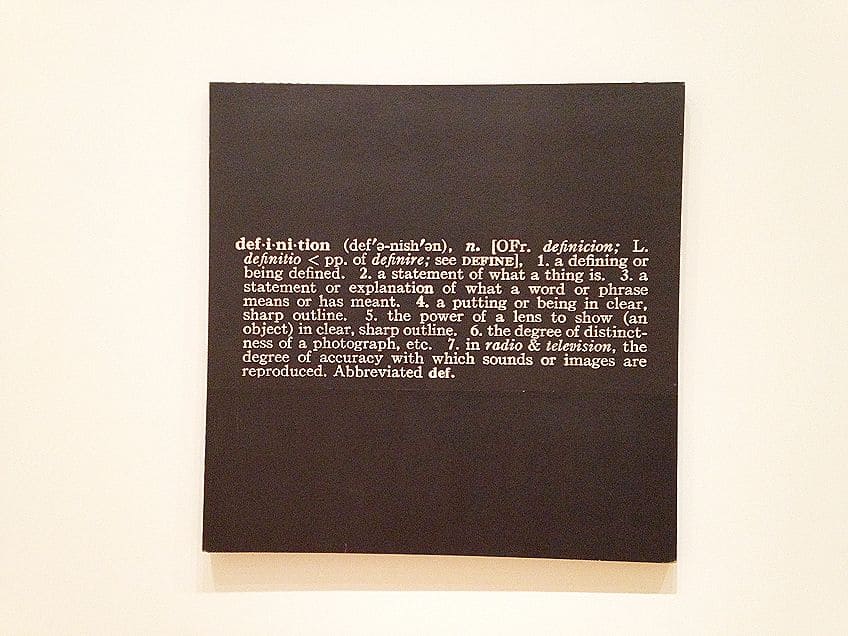

Joseph Kosuth was among the first to take the concept of idea-based art to its rational conclusion, developing a highly critical model founded on the presumption that art must constantly examine its own purpose. Kosuth stated that to undertake this self-criticism, traditional media must be abandoned. He challenged whether art had to be represented in a visual form at all, or whether it had to be represented in any material form at all.

Many people, like Lawrence Weiner, have expressed a desire to abandon the practice of making actual works of art.

Artists attempted to eliminate aesthetic standards and market status from the creative equation by minimizing the materiality of art. As a result, the “dematerialization of art objects” had a significant political underpinning. Conceptual art concepts frequently invoked dispersal (rather than formation) and voiding (rather than creation), and many Conceptual creative ideas were open-ended hypotheses with no predetermined outcomes.

“Art that puts constraints on the receiver for its reception, in my opinion, represents aesthetic fascism,” Wiener remarked.

The Use of Language in Art

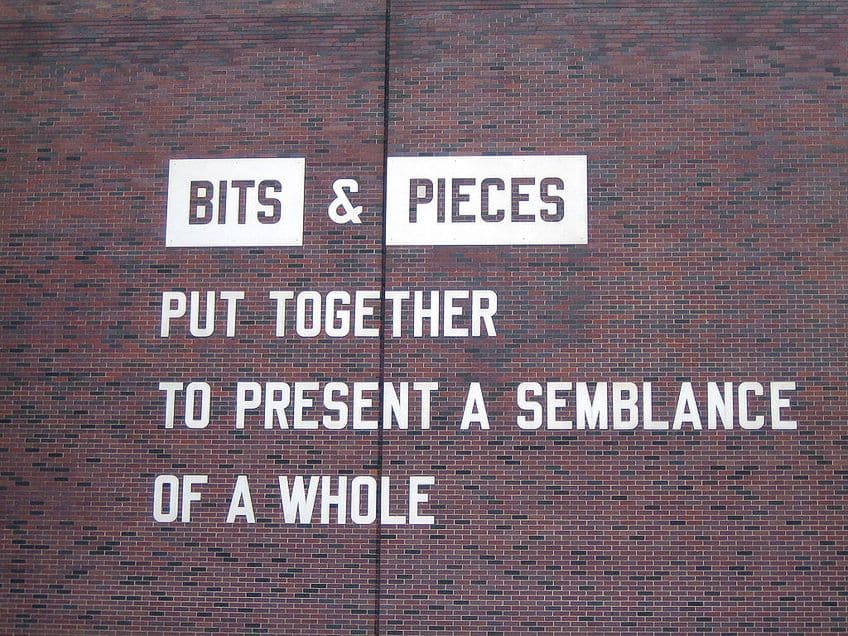

While the utilization of text in artwork was nothing novel by the 1960s – words appear beside other visual aspects in Cubist works, for example – artists like Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, and John Baldessari accepted text as the major element of a visual piece of artwork.

Unlike their forefathers, this generation had attended college, which explains their rationalism and the effect of modern language research.

The phrase employed was intended to represent both itself and an aesthetic concept. Text-based art would frequently utilize abstract formulations to evoke connections for the observer, typically in the form of confusing statements or simply a single word.

While first-wave conceptualists are still active today, they influenced new artists to pursue language-based art.

Anti-Institutionalization of Conceptual Artists

If Conceptual art had a basic concept that unified all Conceptualist artists under one flag, it was undoubtedly their common dissatisfaction with the art world’s institutionalized status as arbitrator of what constitutes “good” vs. “poor” work. Since the mid-19th century, creative guardians had been mostly influenced by business considerations, so “good” art was commercially viable and “poor” art was not. This arrangement benefited a limited group of artists and individuals of an exclusive social group who purchased and accumulated the work or worked in museum management.

There was a perception in the 1960s that if art catered to this environment, it would never question the status quo.

Throughout the 1960s and into the early 1970s, conceptualist artists and theorists attentively examined modern art techniques and tendencies in search of types of revolutionary theory or aesthetics but found mostly a continuance of abstract and minimalist themes. In the late 1960s, artists like Michael Asher, Hans Haacke, and Marcel Broodthaers explored a kind of Conceptualism that became known as institutional critique.

Her Institutional critique carried on the history of idea-based art, but generally in the form of installations that indirectly questioned the museum’s supposed function—the preservation and presentation of masterpieces—by presenting a perspective on its larger position within society at large. The museum is not an impartial space for the presentation of art and public education. It is instead invested in supporting certain artists, selecting “essential” pieces of art, and constructing the economic reality that favors its members and the existing art world.

The fundamental complication of institutionalized critique is that it was frequently staged within the organizations that artists were criticizing. At times, the success of a specific piece was dependent on spectator engagement, illustrating that the work, like the “art world,” involves spectators as well as creators and the organizations that house them.

Therefore, rather than merely dismissing or condemning the institution, these artists frequently entangled themselves and strove to attract attention to the rich web of social and institutional interactions.

Authorship Challenges

When Marcel Duchamp nominated a urinal as an artistic work and released later versions of his Readymades, he dealt a direct blow to the Western concept of creative innovation. By this model, Sol LeWitt argued that the work did not have to be entirely “created” by the artist. “When an artist creates conceptual art, it implies that all of the decisions and planning are determined ahead of time, and the implementation is only a formality. The concept is transformed into a machine that creates art.”

This notion of a mechanized or machine-like implementation of an art idea is characteristic of Conceptualism in general.

This rejection of the artist as the only producer of the work extends to numerous posthumous works in which the artist’s name appears but they are not the creator. LeWitt, who died in 2007, left behind several unfulfilled designs for sculptures and other pieces of art, which are often recreated today by groups of fabricators and helpers, enabling the creation of brand new LeWitt works even after the artist’s death.

Such fabrication of the artist’s name is reminiscent of previous contemporary art methods, notably in sculpture. Whereas authorship is an element of LeWitt’s posthumously published works, the process contradicts conventional views of art and mastery.

The Trend of Photo-Conceptualism

Conceptualism is often related to photo-conceptualism. Conceptual artists frequently depended on photography to capture their concepts, and it was a useful medium for this. Photography might be incorporated into the artist’s vision or system in the same way as a schematic or text could. In this view, the record is the artwork, and vice versa, and as a result, the traditional hierarchical separation between “work” and “record” – where the former is seen as more essential than the latter – is rendered obsolete.

Unlike many photographers, Conceptualists were unconcerned with photographic clarity, whether measured by a printing method, arrangement, setting, or editing.

Moreover, their dryly analytical approach produced images that do not provide the spectator access to the artist’s character and do not elicit a strong visceral reaction. This aesthetically anti-expressive technique to generate photo-conceptual works is exemplified by Edward Ruscha’s matter-of-fact images of Every Building on the Sunset Strip, which he meticulously made with a camera fastened to his pickup truck.

The Legacy of Conceptual Art

Though the Conceptual art approach championed by Joseph Kosuth may be considered the pinnacle of the movement, others pursued pathways that were perhaps just as important. Conceptual art defied standards of workmanship and style to such an extent that it might be considered to reintroduce substance, which had been virtually forgotten due to the critical attention on form.

Conceptualism, which emerged at a moment of tremendous social upheaval, found widespread application by artists seeking to highlight a variety of societal themes.

Global artists such as Martha Rosler, Hans Haacke, Jenny Holzer, and Alfredo Jaar, address societal themes such as work and gendered relations, museum governance, and impoverishment and repression. While the movement frequently highlighted the social structure of artworks, it was not popular and had limited success outside of the art community owing to its obscure perspective.

Furthermore, during the mid-1970s, splits in the movement started to form, eventually contributing to its disintegration.

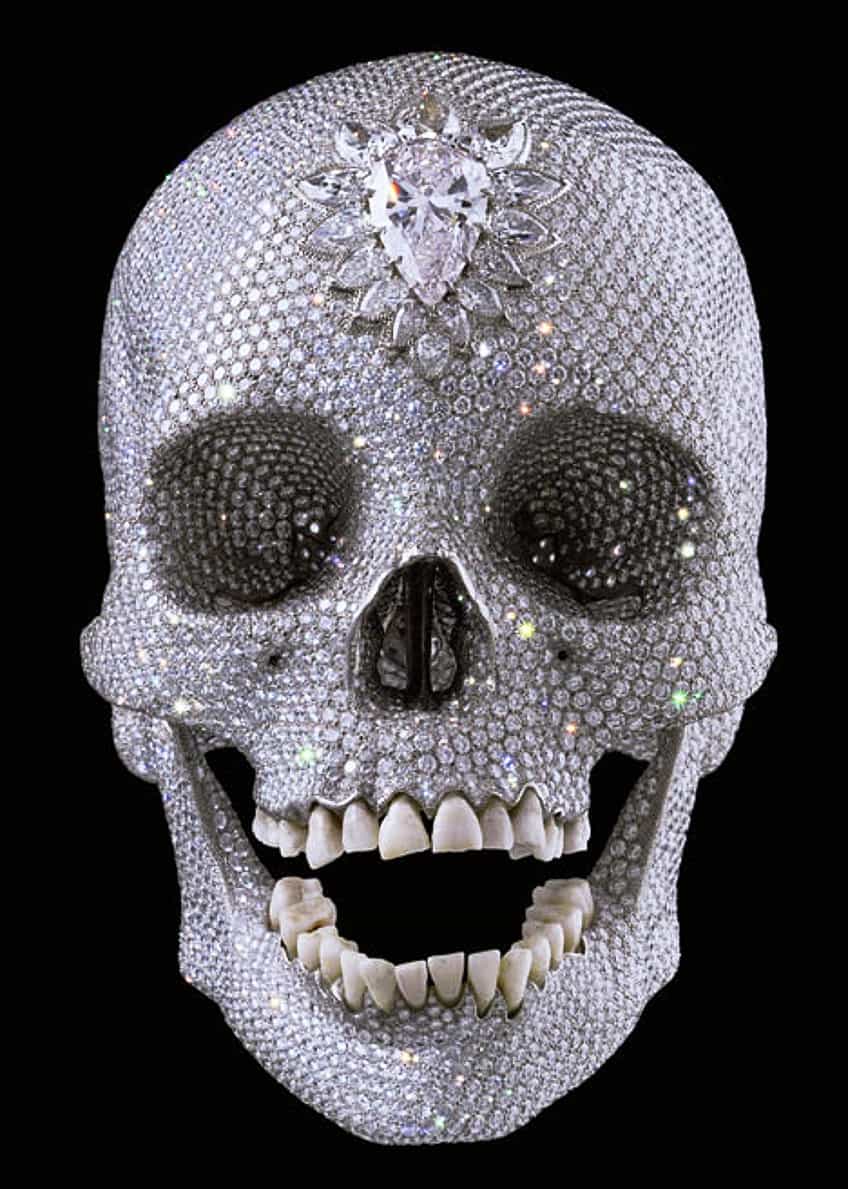

However, it inspired future post-Conceptual creators, many of whom welcomed the material base of artwork and the lexicon of visual culture. Others avoided regular creative creation by using performance art or installations. Many of its themes, as well as some of its stark style and techniques, may be seen in the creations of a wide range of artists, including Tino Sehgal, Andrea Fraser, Gabriel Orozco, and Damien Hirst.

Important Conceptual Artworks

Many Conceptual artists were encouraged to assume that if the artist initiated the artwork, the gallery or museum and the public would finish it in some way. This type of Conceptualism art is known as “institutional critique,” and it may be seen as part of a larger trend away from stressing object-based works of art and toward explicitly reflecting cultural ideals of society at large.

Many works of Conceptual art are self-conscious or self-referential. They, as with Duchamp and other modernists, produced art about art and pushed its boundaries by employing basic materials and even language.

Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) by Robert Rauschenberg

| Date Completed | 1953 |

| Medium | Charcoal, pencil, crayon – erased |

| Dimensions (cm) | 64 x 55 |

| Current Location | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

In 1953, Robert Rauschenberg paid a visit to Willem de Kooning’s apartment and asked that one of de Kooning’s works be entirely erased. Rauschenberg thought that for this notion to become a piece of artwork, it had to be created by someone else rather than him; if he deleted one of his own works, the outcome would be nothing more than a nullified image.

Although first disagreeing, de Kooning grasped the notion and grudgingly agreed to hand away something he would mourn the loss of, and would be difficult to erase completely, making the erasing that much more powerful in the end.

It took Rauschenberg about a month and around 15 erasers to “complete” the artwork. “It’s not a denial, it’s simply the notion!” Rauschenberg once stated. Of course, it also meant the end of Abstract Expressionist painting and the notion that art should be emotive.

The missing sketch is an avant-garde Conceptual work.

Grapefruit (1964) by Yoko Ono

| Date Completed | 1964 |

| Medium | Book |

| Dimensions (cm) | 13 x 13 |

| Current Location | Wunternaum Press, Tokyo |

Grapefruit, Yoko Ono’s incredibly plain-looking and curiously named 1964 book, is a significant early instance of Conceptual art and the relationship between it and Fluxus. Although the piece is technically an item, the art goes beyond its physical limitations since it carries a series of creative “event scores” – varied directions for readers to act out if they so want.

Grapefruit operates as a user’s handbook in the Fluxus style, including 150 sets of instructions organized into five areas (Audio, Art, Occasion, Poetic, and Objects), with a perspective comparable to Joseph Beuys’s that “every living being is creative.”

This book not only devalues the actual thing in favor of the document or platform for creative activity, but it also enables the artworks to be executed by anybody, possibly resulting in a limitless number of artworks emerging from a single source.

Nevertheless, like with other Conceptual works, whether or not the directions are followed is secondary to the creative concept.

One and Three Chairs (1965) by Joseph Kosuth

| Date Completed | 1965 |

| Medium | Wood chair, photo of a chair, photo of dictionary description of a chair |

| Dimensions (cm) | Chair: 82 x 37 x 53; Chair photo: 91 x 61; Dictionary photo: 61 x 76 |

| Current Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

In between a scale image of a chair and a written description of the term “chair”, a physical chair is displayed. This Conceptual art classic by Joseph Kosuth asks what constitutes a “chair” – the actual thing, the concept, the image, or a mix of all three things.

According to Joseph Kosuth, “Conceptual art is so named because it is founded on an investigation into the essence of art. As a result, it is…a consideration of all the connotations, of all facets of the notion ‘art.”

One and Three Chairs rejects the hierarchical difference between objects and their representations, implying that a conceptual work of art may be both a thing and a representation in its numerous forms. This work refers to and expands on the Surrealist René Magritte’s earlier proposal to investigate the perceived precedence of an object over its representation.

Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) by Ed Ruscha

| Date Completed | 1966 |

| Medium | Photographs and fold book |

| Dimensions (cm) | 18 x 14 |

| Current Location | Walker Art Center, Minneapolis |

Ruscha strapped a camera to the rear of a truck and drove up and down the Sunset Strip, photographing both sides of the avenue for this photographic study. The concept is transformed into a machine that creates art. The book was a notable reinterpretation of the conventional photographer’s book, lavishly bound to accentuate the high-quality reproductions included within. Much of photography’s history was spent attempting to establish photography as an art form, as seen by the work of Edward Weston and Alfred Stieglitz.

Ruscha’s abstraction of the subject matter through fascinating cropping, precise editing, or striking contrasts of light and shadow did not aim to exalt the craft of photography as one might assume.

He does not advertise his photographic abilities. He photographed during high noon under harsh lighting, giving the images an unprofessional appearance; and rather than artistically framing the image, he employed the “strip” as a ready-made shape to which his aesthetic selections were subject.

He, like many of his age, opposes the notion that artwork should be a reflection of a distinct aesthetic vision or identity. Ruscha’s candid document is indicative of the anti-expressionist stance evident in many art photographs from the 1960s to the present, including works by Thomas Struth, Bernd and Hilla Becher, and Rineke Dijkstra.

A significant contrast between photo-conceptualist work and many other examples of what has come to be known as “deadpan photographs” is that the photo-conceptualist method is journalistic and prioritizes the display of professional photographic methods over the representation of the idea.

| Date Completed | 1969 |

| Medium | Photo of performance |

| Dimensions (cm) | 74 x 86 |

| Current Location | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

Midway through the 1960s, Dan Graham started to explore the moving picture and 360-degree topographic rotation. He then came up with the idea for Two Correlated Rotations, an extremely difficult exercise requiring two performers. This essay “relates perceptions to apparent motion and to the impression of depth and time,” according to Graham.

Each performer concurrently followed a planned circular course, snapping continuous images of each other as they traveled.

One performer stood inside a defined circle or contained location while another stood outside. While confounding the observer by rotating this eye in diverging 360-degree arcs, Two Correlated Rotations put observers in the cameraman’s mind’s eye. The photographic documentation and the double-synchronous pictures, which are shown as a single work, draw attention to a job that had a specific shape but resulted in quite varied visual interpretations of that creative notion.

Each camera “mirrors” the filmmaking process, continuing the modernist legacy of self-reflexivity. The project is a video about its own production, but it obviously also relies on live performance and many static graphics and diagrams to convey the artist’s notion.

Conceptualism’s strategy is to embrace multiple mediums.

MoMA Poll (1970) by Hans Haacke

| Date Completed | 1970 |

| Medium | On-site installation |

| Dimensions (cm) | 29 x 25 |

| Current Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Haacke created a survey for the Museum’s 1970 exhibition Information in which guests would be asked to cast a ballot on an existing sociopolitical problem and offer up their responses in writing. The set of questions would be placed in one of two translucent boxes, enabling citizens people to estimate the number of submissions.

According to the poll’s question: “Would Governor Rockefeller’s failure to criticize Nixon’s policies prevent you from supporting him in November?”

Since Governor Rockefeller was a significant supporter of the institution as well as a committee member, this topic, which was not presented to the museum before the launch of the display, struck at the very core of MoMA as an organization.

There were clearly double as many YES votes as NO votes, making the outcome all the more stunning considering the poll’s setting and setting. Haacke’s MoMA Poll is an important exemplar of Conceptual art’s politically driven style of institutional critique, but it should not be confused with an unbiased poll.

The piece, which was started by the artist, had an unexpected ending that was only finished by the audience.

In this approach, Haacke argues that it is not just the artist’s responsibility to create a piece of art. All art pieces rely on an agreement to be recognized as works of art. This piece reflects the concept that an artistic production is a group rather than an individual endeavor.

Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, Financial Section (1971) by Marcel Broodthaers

| Date Completed | 1971 |

| Medium | Cold bar with eagle stamp |

| Dimensions (cm) | 59 x 42 |

| Current Location | Galerie Beaumont, Luxembourg |

Between 1968 and 1971, Marcel Broodthaers established his institution as a transitory conceptual museum that would materialize as installations in “parts” at various periods and locations. Broodthaers declared the Museum bankrupt in 1971, emphasizing the economic operation of cultural organizations; he created a parallel Financial Section through which he attempted to acquire cash by the sale of specially produced gold bars.

Each glittering bar was priced by Broodthaers with an eagle imprint at twice the price of gold at the time, converting the market for gold from one of commerce to one of art.

The bars, which are both an investment and an actual item, were regarded relatively highly as works of art. The rising price of the gold bar proved that the value of commodities and gold is speculative and thus determined by the market.

Duchamp had already said with his Readymades that there is no particular essence or character to art other than the fact that it has been selected or proposed by an artist and is subsequently recognized as such by the artistic establishment, which includes the art market. By using the environment of his made-up museum to “convert” the gold into art, Broodthaers makes this point very evident.

The buyer would help clinch the deal that it was a legitimate artwork and not just gold by purchasing the gold. With a note of authenticity given to the buyer, the artist would approve the piece of art. Broodthaers is recognized as an artist engaged in “institutional critique” partly because of the Museum series, but it’s vital to remember that this critique is not just denial or contempt of the art world.

Instead, it takes the shape of a continuous illumination of the interdependency of the creator, the work, and the structures that display and advertise it, frequently through subtle mockery.

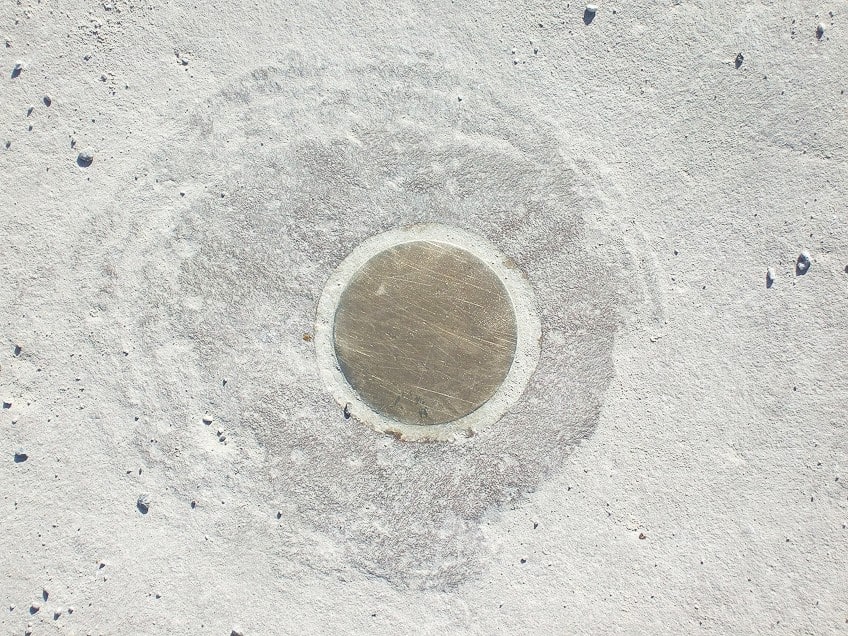

The Vertical Earth Kilometer (1977) by Walter de Maria

| Date Completed | 1977 |

| Medium | Sandstone plate, brass rod |

| Dimensions | 1-kilometer |

| Current Location | Friedrichsplatz Park, Kassel, Germany |

The idea behind this piece was to create an actual but undetectable artwork. De Maria used a production drill to dig a one-kilometer-deep pit, then plugged a two-inch-diameter brass rod of the very same length and covered it with a sandstone plate. A tiny hole was cut in the center of the plate to disclose a part of the rod that is absolutely level with the ground.

As a result, individuals are compelled to envision yet may never witness a timeless work of art.

As a counterpart to this work, de Maria developed the considerably more apparent Broken Kilometer (1979), which comprised 500 two-meter-long brass rods carefully set on an exhibit floor area in five parallel rows of 100 rods each. This piece, in keeping with Conceptual artists’ rejection of conventional techniques and formal concerns, challenges the marketplace: it cannot be sold or fully presented.

Furthermore, because of its simplicity and mainly veiled nature, it is anti-expressive and compatible with the period’s numerous contradictory negations of the visual in “visual art.”

Imponderabilia (1977) by Marina Abramović

| Date Completed | 1977 |

| Medium | On-site performance |

| Dimensions (cm) | N/A |

| Current Location | Galleria Communale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna |

Marina Abramović and her lifelong lover Ulay faced each other, entirely naked, and flanked the museum’s entrance, forcing people to turn and squeeze past the naked bodies to access the building. While the performance is intended to bring instant attention to the actors’ nudity, the actual notion at work is the investigation of the audience’s response to the nakedness, the performers’ positioning, and, most significantly, how individual visitors opted to enter.

Do they appear shy or ashamed as they approach? Do they prefer to face the performers while attempting to pass through?

The performance’s subsequent photos and videos serve as a kind of case study on how people behave when presented with extremely bizarre or frightening situations. Their work shows the connections between conceptual art and performance, which are typically seen as distinct trends, but it also sets itself apart from much conceptual art by making frequent references to the body, taking risks, and balancing the suspense between the artists’ indifference and the possibility of an intense emotional reaction to the work.

As we can see from our list, Conceptual painting was not as significant as other forms of Conceptual art, such as installations, performances, and strange items. The idea that only concepts may be pieces of art and that they are in a process of creation that may finally take some shape was one of the basic conceptions of conceptual art. Not all concepts must be realized physically. The Conceptualist art movement was not as much a typical movement as it was a set of ideas and strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Conceptual Art?

The 1960s saw the emergence of conceptual art—at least in its Western form—as a response to Clement Greenberg’s adamant devotion to formalism and works of art like Abstract Expressionism that focused on the picture plane’s flat surface. In his groundbreaking publication, Sol LeWitt defined the parameters of conceptual art. The concept or idea is the most crucial component of conceptual art. When an artist employs a conceptual style, it indicates that all of the preparation and choices have been determined in advance and that the execution is merely ceremonial. All conceptual artists are aware of the theoretical character of their work. Many Conceptualism artists reinforced this by decreasing the quantity of material in their works.

What Is the Conceptual Art Definition?

Instead of creating art with a concept, conceptual art questioned the idea of art. This inquiry, which is not limited to any one media, has traditionally been associated with white males in large numbers. Interacting with conceptual art is sometimes characterized by the feeling that the piece’s key, the revelatory notion is tucked away in the corner of your mind, just out of reach. You may believe that an idea isn’t worthwhile finding if the conceptual effort is poor. An excellent one encourages you to continue looking. Curators must always grapple with how to make conceptual art palatable without giving viewers a stomachache. One constant difficulty is giving viewers the information they need to reach that primary notion, or set of methods, without overloading them. The simplicity of minimalism motivated the Conceptualist art movement, although they disagreed with minimalism’s embrace of rules as the pillars of artistic creativity.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Conceptual Art – A Look at the Important Conceptualist Art Movement.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. July 22, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/conceptual-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 22 July). Conceptual Art – A Look at the Important Conceptualist Art Movement. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/conceptual-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Conceptual Art – A Look at the Important Conceptualist Art Movement.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, July 22, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/conceptual-art/.