Avant-Garde Art – Pushing the Boundaries of Art

What is Avant-Garde? What makes this art movement particularly “modern”? These are just a few questions that we will be answering in this article concerning one of the most radical art movements of the 20th century. The Avant-Garde period in art history offered artists the opportunity to present their most unorthodox and Contemporary modes of making and visualizing art in light of viewpoints and concepts that challenged the norm across society, politics, art, and culture. In this article, we will explore different forms of the Avant-Garde art style through some of the most famous Avant-Garde paintings and their creators.

Challenging the Status Quo: An Introduction to Avant-Garde Art

What is Avant-Garde? What does Avant-Garde look like in art? And what does this movement mean in the broader art historical canon? These are some of the questions you may have about the “umbrella movement” known as the Avant-Garde, which officially emerged in the late 19th century and made its presence known throughout the 20th century.

The term “Avant-Garde” originally refers to a French military reconnaissance group and translates in English to “vanguard” or “advance guard”, as a group meant to scout the field ahead of the main militant force. The term was also associated with 19th-century left-wing French radicals who advocated for political reform and thus informs the foundational spirit of the Avant-Garde art movement.

The idea of reform itself and the suggestion that art could be a tool for leading reform was what informed the Avant-Garde style. The desire to enact social change through art was the introduction of the idea of reform into society and soon shifted from an emphasis on social issues to a more artistic and culture-centric mission. Modern ideas of the Avant-Garde revolve around the notion that the movement consists of a group of artists, thinkers, intellectuals, writers, and architects who approach art with an expressive voice and propose experimental methods of challenging existing cultural values.

To summarize, Avant-Garde art is any art that proposes modern or innovative ideas through new forms or themes. Historically, the Avant-Garde challenged the boundaries of the status quo according to the arts and culture spheres and is often considered to be one of the most direct art movements that aided in the birth of Modernism. An essay by Olinde Rodrigues in 1825 called The Artist, the Scientist, and the Industrialist was the first paper to use the term Avant-Garde in the modern sense.

It was essentially an open call to artists to become the people’s Avant-Garde and in a sense, to wield the power tool of art as a force for social, cultural, economic, and political reform.

Vanguardism and Theories of the Avant-Garde

Theories of the Avant-Garde and what it means for the role of the artist as a proponent of socio-cultural reform have long been debated in light of political vanguardism as popularized by Vladimir Lenin. This political concept refers to a strategy employed by the politically advanced and class-conscious citizens of the working class who come together to form organizations aimed at driving action via revolutionary politics. Revolutionary vanguardism was a form of proletarian political power that challenged the bourgeoisie.

In 1939, the famed art critic Clement Greenberg published an essay called Avant-Garde and Kitsch, which argued that Avant-Garde art and Modernist art were tools to resist the oversimplification of culture, as incited by the growth in consumerism, which spread like wildfire in the 20th century. Greenberg also proposed that vanguard culture was historically placed in opposition to mainstream consumer culture and that it served as a rejection of artificial mass culture brought on by Industrialization.

Greenberg also made a fair point in highlighting the impact of capitalism and its products found in mainstream culture that has historically borrowed popular imagery from major art movements and adopted such imagery or mannerisms to fuel the machine of consumerism, mainstream media, and advertising tactics.

An Italian intellectual named Renato Poggioli further analyzed the role of vanguardism in a book published in 1962 called The Theory of the Avant-Garde, which traverses the social, psychological, historical, and philosophical categories of vanguardism to demonstrate the inherent shared values of vanguardists that transcend the individualist spheres of the arts and show up through non-conformist lifestyles.

Vanguard culture, and thus the foundation of the Avant-Garde, could also be regarded as a sub-movement of Bohemianism, which revolved around the practice of an unconventional lifestyle.

Timeline of Avant-Garde Art

Since Avant-Garde art relies upon the foundation that the art produced must be innovative and propose new or modern art forms and subject matters, it can be difficult to compact the timeline of the movement. We can, however, pinpoint the origins of the first direct reference to the essence of Avant-Garde in the work of Realist painter, Gustave Courbet, who proved incredibly influential due to his then-modern approach to painting, which was informed by early Socialist ideas in the 19th century.

The idea behind Avant-Garde art is that the art produced usually carries some sort of shock value that goes against the existing norm of the time. This is also why Avant-Garde art is so closely associated with Modern art and concepts of the modern since it strives for innovation and enhancement. The Avant-Garde can be more easily understood in retrospect since the idea of originality and innovation in the art can have you questioning “what has not been done? And if originality truly exists anymore.

Most Avant-Garde artworks and their creators will often be associated with controversial criticism due to the nature of challenging the norm. Some key art movements under the umbrella term of Avant-Garde include the Impressionist movement of the mid-19th century, which saw the establishment of a Salon des Refusés that hosted the rejected works of many artists who challenged the artistic conventions of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Artists like Gustave Courbet and Camille Pissarro were criticized for their unique approaches to unique Avant-Garde styles.

These did not cater to the general public and agreed-on stylistic social conventions but catered to an approach led by experimentation and the subversion of ideals.

Significant Avant-Garde Movements

Now that we have a general understanding of what Avant-Garde art is, we can now examine the different ways that it has emerged in history. Below, we will discuss some of the most profound Avant-Garde movements that paved the path forward for Modernism.

Dadaism

The Dada movement was the first art movement that was directly based on the idea of anti-art and a rejection of culture and values that promoted the violence caused by World War I. The term “Dada” in Russian translates to “Yes-Yes” and in German as “There-There”. The Dadaism movement quickly gained traction in Europe and America around 1916 and was first coined by Hugo Ball and Richard Huelsenbeck who selected the term from a German-French dictionary.

The aim of Dadaism was built on the desire for art to reflect a true or accurate perception of the present moment in history.

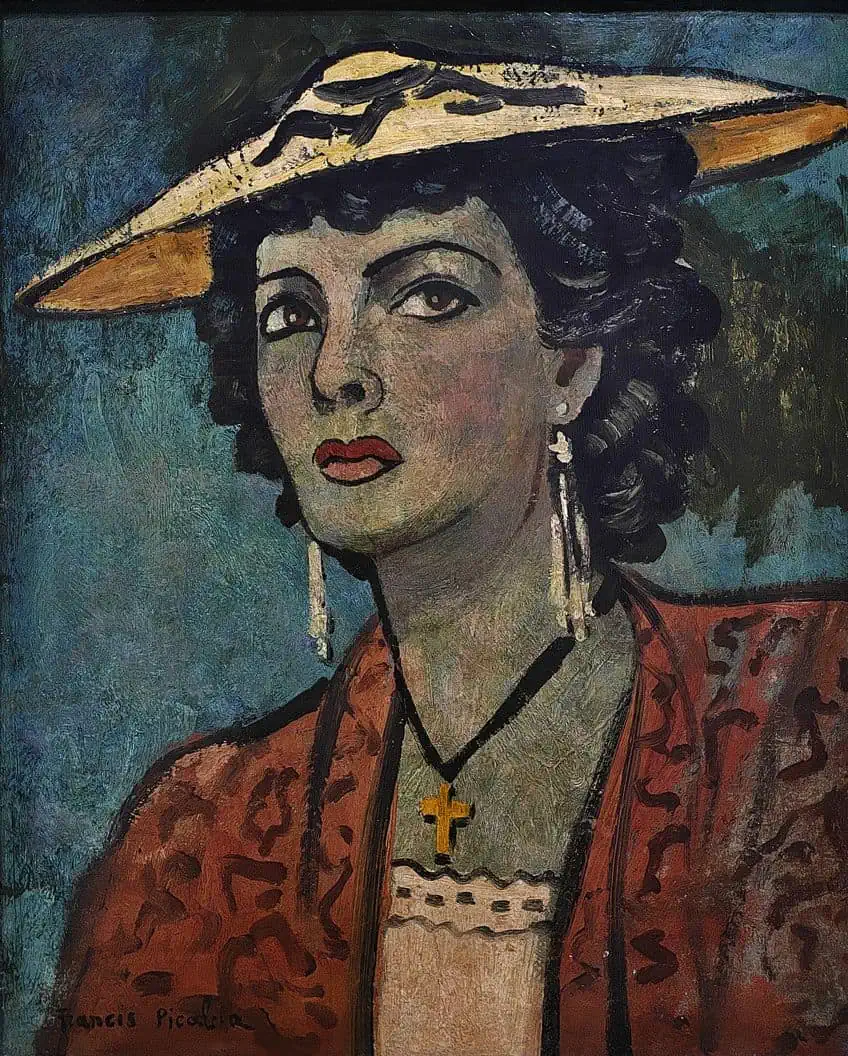

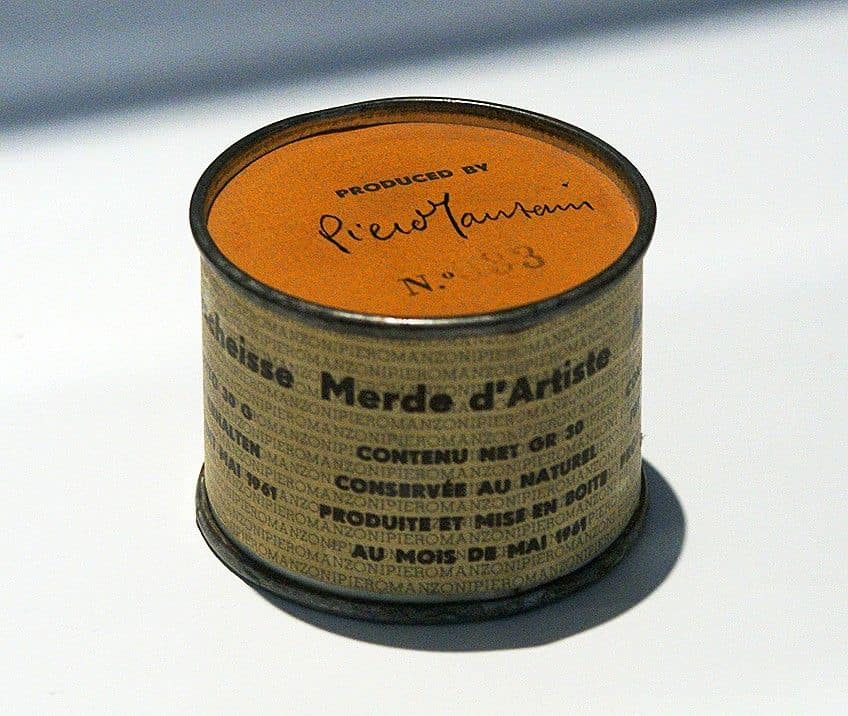

The Dadaists were known for their direct demonstrations and performances along with the production of many manifestos and exhibitions that aimed to shock and fight the idea of the “establishment”. Some of the most famous artists from the Dadaist movement include Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Max Ernst, and Jean Arp. The most prominent feature of Dadaism was the idea of readymades in sculpture, which was founded on the basis that art could be made from found materials and adapted in a variety of ways.

Impressionism

The age of Impressionism began in the 19th century and can be regarded as one of the most famous Avant-Garde movements. Although the revolutionary aspect of Impressionism was not as well-received or harsh as the movements of the following century, it is still one that prioritized the independent art style of the artist and was mostly founded on the rejection of academic art styles and norms for what good art was. Some key figures from the movement include Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and Édouard Manet.

Constructivism

Constructivism was a movement founded in Russia in the early 20th century by Vladimir Tatli and revolved around art and architecture. The movement dismissed traditional teachings of art and favored art as a tool for achieving social missions. The movement was essentially the construction of the Socialist regime and reflected the combination of art and politics that consisted of artwork made from industrial materials. The art of Constructivism was not as much focused on abstraction as it was on political purposes and dismissed painting as an effective medium for pushing its agenda. The popular mediums in Constructivism include ceramic sculpture, architecture, and design across fashion and graphics.

The Realist Manifesto is one of the most famous manifestos of Constructivism that detailed a favored outlook on technology and machines over traditional art.

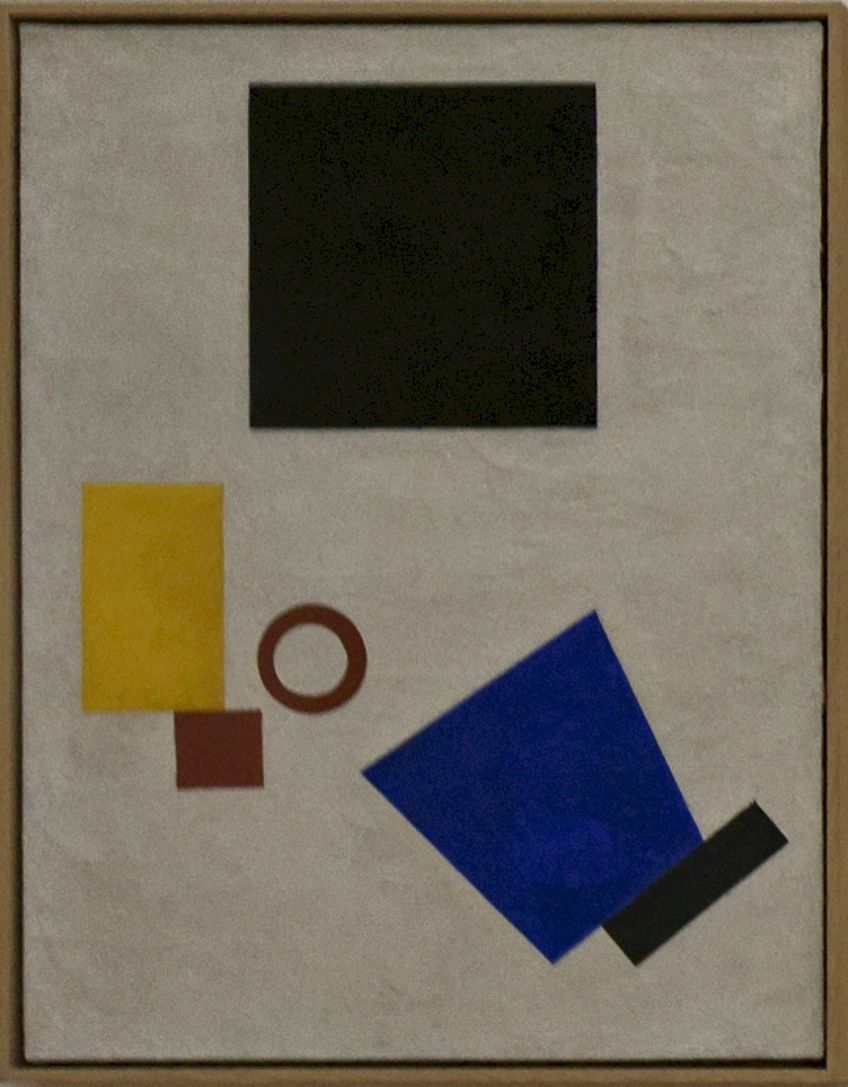

Suprematism

Another Russian Avant-Garde movement was Suprematism, which co-existed with Constructivism and was focused on abstraction and geometric shapes in painting. The founder of the movement, Kazimir Malevich, and his contemporaries believed that art should revert to its basic components and prioritized geometric abstraction, primary, and neutral colors. Suprematism also differed from Constructivism in that it was founded on mysticism and spirituality realized through abstraction. Malevich described the role of abstraction in Suprematism as a way to “free art from the dead weight of the real world”.

Futurism

Futurism emerged in Italy around the early 20th century along with similar movements in Russia and England that emphasized youth, technology, speed, and violence. The movement sought to embrace change and connect the dots between humans and the machine. The idea of Futurism is built on the controversial Avant-Garde approach that discards traditional cultural and artistic forms and endorses war.

Futurism was established by Filippo Marinetti in 1909 and travels across multiple art forms such as theater, literature, film, ceramics, and graphic design. Popular themes of Futurism include cars, large crowds, dancers, animals, and trains.

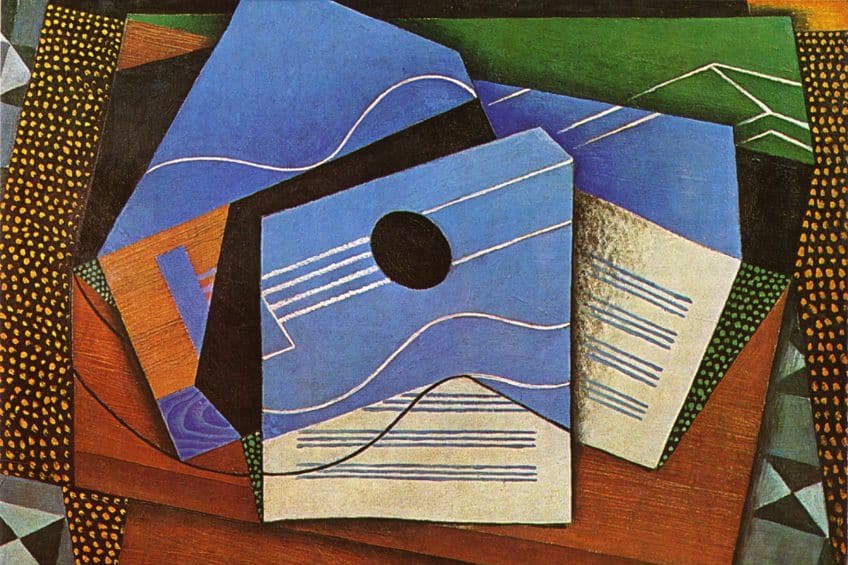

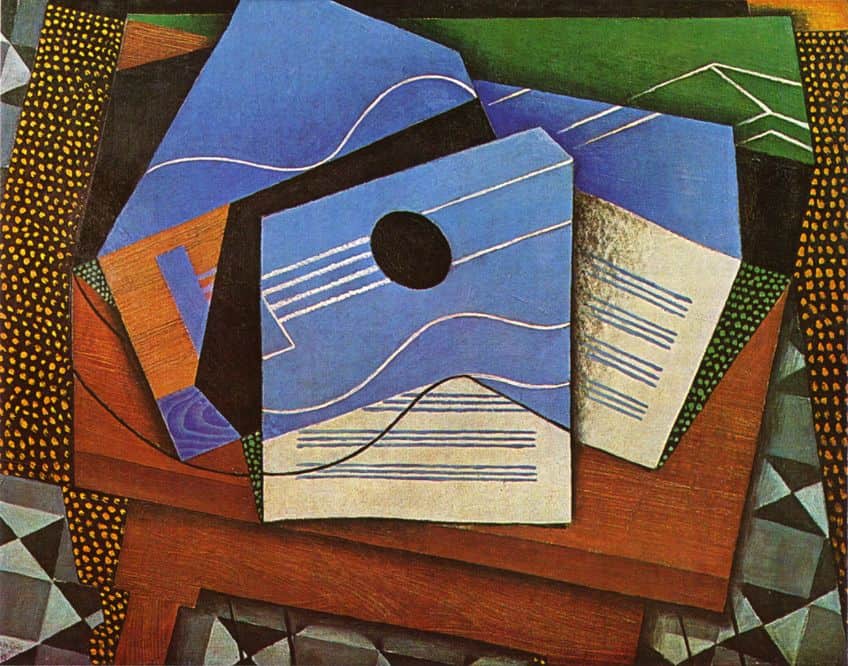

Analytical Cubism

Analytical Cubism is one of the most intellectually driven Avant-Garde movements that rejected the idea of linear perspective and favored the idea of the two-dimensional picture plane. As one would imagine, this would have shocked the European academies as they witnessed the emphasis on flat dimensionality over the mimicry of nature. Avant-garde artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque stand at the forefront of the Analytical Cubist movement.

Photography Under the Avant-Garde

The emergence of photography in the 19th century marked the beginning of added creativity across portraiture and superimposition of Avant-Garde methods at a fairly low cost. The medium itself can be considered Avant-Garde for its ability to document the environment around us and become a tool of modern consciousness. Some of the most pivotal artists of photography in the Avant-Garde sphere include Man Ray, Alexander Rodchenko, Albert Renger-Patzsch, El Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy, and August Sander.

The rise of the medium also marked the birth of many Avant-Garde photographers who sought to capture the essence of Contemporary industrial technology.

France was the hotspot of Avant-Garde photography and drew from the influences of Surrealism, which strove for the rejection of bourgeois conventions and instead advocated for social transformation. Photographers who leveraged Surrealism utilized photographic techniques such as reversed tonality, combination printing, and double exposure to alter the image of reality and thus blur the lines between reality and the dream state.

The Influence of Science on the Avant-Garde

The notion of Modern or Avant-Garde in art was also informed by scientific discoveries and technological advancements that were integrated into different art movements. New methods of painting and visual expression such as Pointillism were informed by the emergence of new studies based on the way that the human eye processes light and is an example of how art draws from science and technology to advance what we identify as “modern art”. Italian Futurism also saw the promotion of modern technology and can be seen in the work of Umberto Boccioni.

On the other hand, artists under Surrealism were influenced by Sigmund Freud’s work on psychoanalysis, and dreams, as well as Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

Innovation across science and technology provided the tools and structure required for the development of methodology surrounding the role of the artist and the artwork. According to Donald Kuspit, an art historian, the Constructivists viewed themselves as technicians, which birthed the creation of artwork that appeared to be mechanical as opposed to works made by hand.

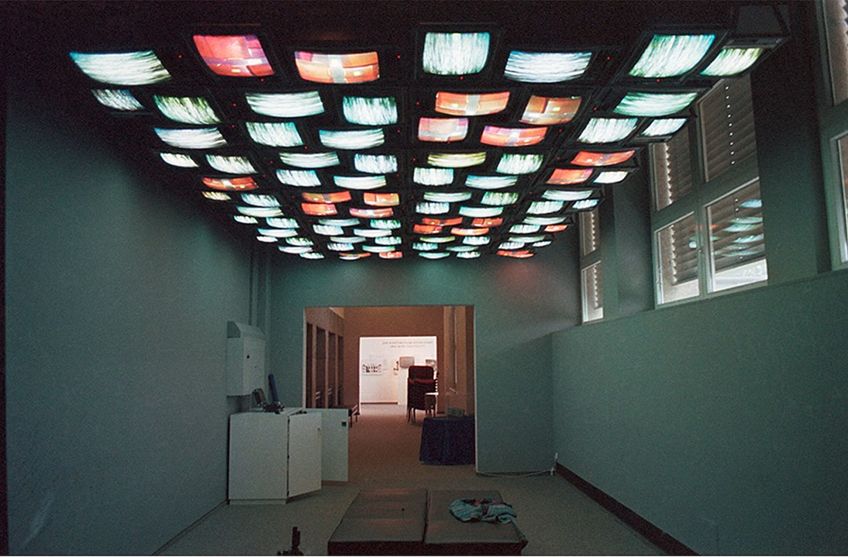

Post-WWII: The Neo-Avant-Garde

Following the end of the second World War, the development of Avant-Garde art transitioned into the Neo-Avant-Garde, which was informed by the stabilization of global culture and politics. The most important aspect of the Neo-Avant-Garde period was the rapid increase in the spread of media and the highly influential art movement known as Fluxus or Neo-Dada.

The Fluxus movement encapsulated more than just the visual arts and included poetry, musical compositions, and an increasing popularity in performance.

The height of the Fluxus movement saw its peak in the 1960s and 1970s when artists from around the world came together to participate in a series of happenings informed by multi-media productions. Artists such as George Maciundas, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono are considered popular figures of the movement.

Famous Avant-Garde Artworks

Avant-Garde art demonstrates not only a wide variety in thinking away from traditional notions of what art is meant to look like but also presents an opportunity from which one can imagine alternative methods and approaches to altering the perception of art and its function. In an era where social issues are constantly on the rise without many tangible real-world solutions, perhaps one can think about how the concept of Avant-Garde can shape solutions from within the art sphere.

Below, we will explore some of the most famous Avant-Garde artworks and how they have altered the perception of art throughout history.

The Third of May 1808 (1814) by Francisco de Goya

| Artist Name | Francisco y Lucientes Goya (1746 – 1828) |

| Date | 1814 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 268 x 347 |

| Where It Is Housed | Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain |

The Third of May is considered to be one of the greatest Avant-Garde paintings of the 19th century, which was created by one of the best Spanish painters of the time, Franciso de Goya. De Goya was deaf at the time of creating this painting and intended to commemorate the Madrid uprising that occurred the day before. You may be wondering why this work is considered to be an Avant-Garde painting in the first place. Its modernity lies in the fact that De Goya negated the traditional approach to Baroque painting and Neoclassical conventions that excluded any heroic figures from the subject and only highlighted the victims of the uprising. By doing so, De Goya draws attention to the atrocities as opposed to the glorified heroism, which further reiterates the theme that he does not celebrate the noble cause because of the amount of bloodshed that results from such uprisings.

For Goya, there is no well-intended aim in the cause, only purposeless death. It is unclear as to when the painting was first shown or if it were well-received by the public, but it is known that later Avant-Garde artists like Édouard Manet used the painting as a reference for The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867-1869). The painting is accompanied by a sister painting called The Second of May 1808, which portrays the riots in Madrid where the local people launched an attack on the French soldiers.

The Third of May portrays the early hours of the morning following the uprising with a French firing squad and a group of executioners who appear to resemble automaton-like creatures. The main figure is the man with his arms outstretched toward the sky who is believed to be a local laborer. His pose is reminiscent of the crucifixion scene in many religious paintings. The rest of the members of the group awaiting their execution include a monk who is kneeling on the floor in prayer as the two are surrounded by their dead compatriots. The reference to the crucifixion is Goya’s way of highlighting that the dead men are martyrs who at the same time illustrate that the act of sacrificing human lives is tragic and thus becomes a modern, Avant-Garde message.

Both paintings were completed after Ferdinand VII returned to Madrid in 1814.

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1862) by Édouard Manet

| Artist Name | Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883) |

| Date | 1862 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 208 x 264 |

| Where It Is Housed | Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France |

Le Déjeuner Sur l’herbe is perhaps one of the most famous Avant-Garde paintings in art history, which was created by Impressionist Édouard Manet in 1862 for consideration in the annual Salon exhibition. Back in the 19th century, such a painting was seen as scandalous and vulgar, which in retrospect qualifies the painting as a Contemporary and Avant-Garde scene.

What makes the painting so Avant-Garde is that it first rejected the social norms of the time in terms of its subject matter and display of the female nude in a very public and social setting. The other Avant-Garde aspect of the painting is found in the size of the artwork itself. The large 208 x 264-centimeter canvas was unusually large for its subject matter since most large paintings of this size were reserved for historical or mythological scenes.

Manet’s brushwork, subject matter, choice in canvas size, and presentation of the female nude were a powerful combination of Avant-Garde elements that influenced later Avant-Garde works and thus the birth of Modernism.

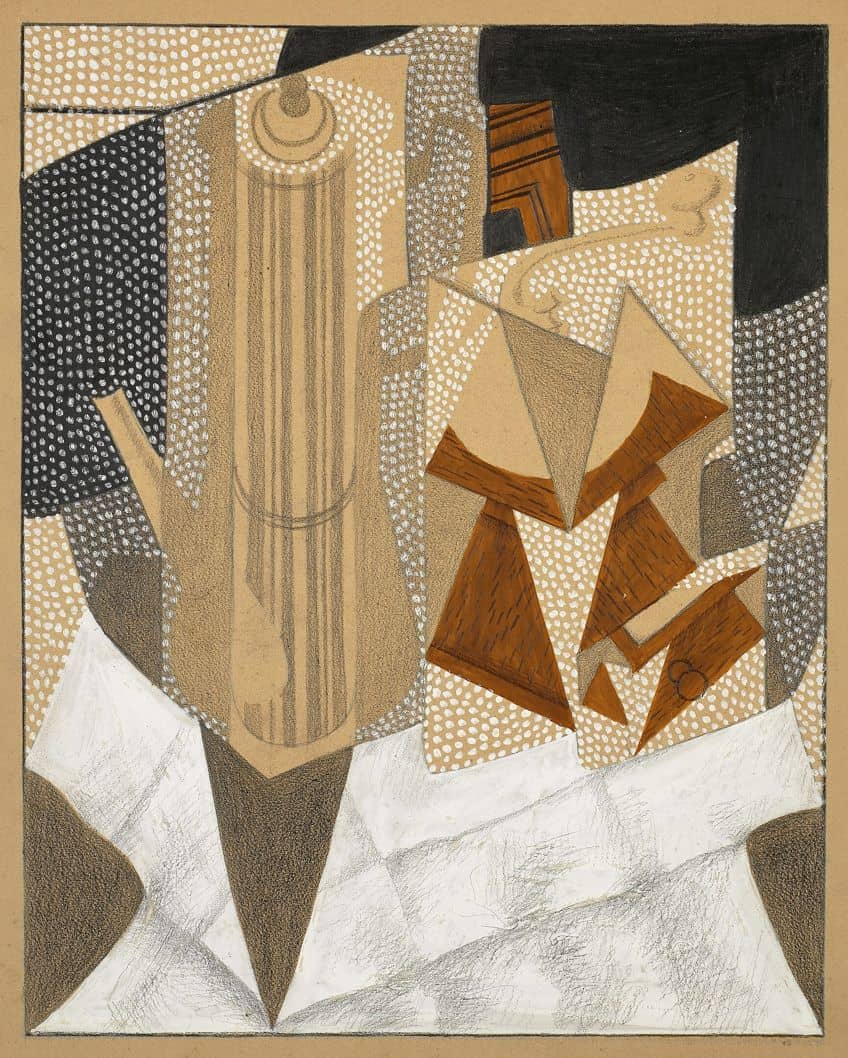

Bottle and Fishes (c.1910 – 1912) by Georges Braque

| Artist Name | Georges Braque (1882 – 1963) |

| Date | c. 1910 – 1912 |

| Medium | Oil paint on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | Support: 61.9 x 74.9 x 2, and frame: 85.6 x 98.4 x 6.7 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate collection, London, United Kingdom |

Georges Braque was one of the most famous Fauvist painters of the 20th century whose works Bottle and Fishes can be considered Avant-Garde. Braque was a pivotal figure in the development of Cubism and the transition to Fauvism. Bottle and Fishes illustrates a distorted perception of the subject matter, which features a bottle with fish on a plate. The still-life is set on a table with a drawer yet it is unclear as to the details of each element.

The only definitive visual element that makes the painting Avant-Garde is its unique blend of a limited color palette with the use of geometric angles to outline the shapes of the elements in the painting without alluding to any detail on its physical body. The painting defies Cubist styles through its brushwork, which adds dimension while presenting the objects as flat, muted, blended, and almost camouflaged with the woodwork of the table. The introduction of vivid colors and especially rough brushwork were characteristics of Fauvist artworks, which rose to prominence between 1905 and 1910.

Bottle and Fishes are regarded as anything but Fauvist in nature due to their subdued palette and domestic subject matter, which can be understood as Braque’s rejection of the luminosity of his earlier Fauvist work.

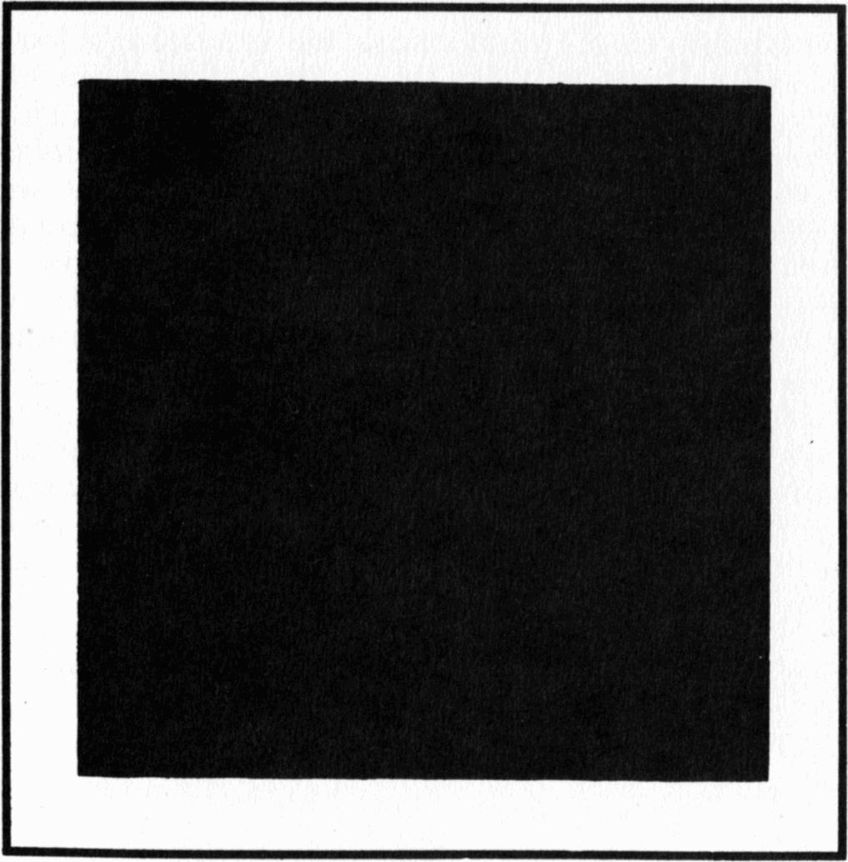

Black Square (1915) by Kazimir Malevich

| Artist Name | Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (1879 – 1935) |

| Date | 1915 |

| Medium | Oil on linen |

| Dimensions (cm) | 80 x 80 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia |

Black Square is the most iconic Avant-Garde painting of the 20th century that depicts a plain black square against a neutral background. The painting was created by Russian Avant-Garde theorist Kazimir Malevich who also produced three other black squares in the 1920s and 1930s.

The first Black Square debuted in 1915 and was inspired by a 1913 stage curtain design that Malevich created himself for a Russian Futurist/Cubo-Futurist opera. A detailed analysis of the original painting indicated that Malevich painted the square over a colorful composition. Historically, the painting is often referenced as one of the most modern paintings of the early 20th century with Malevich himself stating that the work was driven by Suprematism.

Suprematism was essentially the filler episode between Futurism and Constructivism in Russian art.

Fountain (1917; replica 1964) by Marcel Duchamp

| Artist Name | Henri-Robert Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) |

| Date | 1917; 1964 |

| Medium | Readymade sculpture; porcelain |

| Dimensions (cm) | 36 x 48 x 61 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate collection, London, United Kingdom |

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp is perhaps the most famous Avant-Garde Dadaism artwork to date that made use of a readymade signed urinal as the artwork itself. According to Duchamp, the idea of the urinal emerged from a conversation with Walter Arensberg and Joseph Stella.

He submitted the work to the newly established society called the Society of Independent Artists, which was founded by Duchamp himself. The board of directors was required to accept all submissions from members yet they rejected Duchamp’s Fountain for the reason being that it was seen as indecent if exhibited to women.

Duchamp’s own society rejected his submission yet Duchamp went on to create other artworks that attracted a large following.

The Art Critic (1919 – 1920) by Raoul Hausmann

| Artist Name | Raoul Hausmann (1886 – 1971) |

| Date | 1919 – 1920 |

| Medium | Lithograph and printed paper on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 31.8 x 25.4 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate collection, London, United Kingdom |

Raoul Hausmann was the founder of the Berlin Dada group who leveraged photomontage as an art form to express satire and act as a form of political protest.

The Art Critic is a famous lithograph by Hausmann featuring an anonymous figure with a small portion of a German bank note sticking out behind the figure’s neck. The suggestion in the image is that the art critic is essentially controlled by Capitalist structures.

The non-traditional medium of a photomontage coupled with selective imagery and anti-art placement is what makes this work Avant-Garde.

Indestructible Object (1923) by Man Ray

| Artist Name | Man Ray (1890 – 1976) |

| Date | 1923 (original); 1933 (copy); 1958 (remake); 1965 (copy with edition) |

| Medium | Wooden metronome and photograph, black and white, on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 21.5 x 11 x 11.5 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

Indestructible Object was previously titled Object to be Destroyed and was first created by Avant-Garde artist Man Ray in 1923. The installation features a metronome with an image of an eye attached with a paperclip to the swinging arm. Ray described his use of the metronome when engaged in painting as a tool that he used to paint with according to the frequency of the ticks and the number and pace of brushstrokes he used.

In 1933, Ray remade the object and included the eye of his lover who had just left him. Ray also left instructions on a drawing he made of the new object, which addressed the level of his pain. The 1933 Indestructible Object was lost to the German invasion of Paris in 1940 and another copy was produced in 1945 for exhibition in New York. In 1957, the artwork was also included in a Dadaist exhibition, which was a memorable event for Ray since a group of students from the Académie des Beaux-Arts delivered a protest at the exhibition, on the same day that Ray was present in the gallery. In 1958, the Indestructible Object had undergone reconstruction where it also acquired its current title and in 1965, Ray partnered with French artist Daniel Spoerri to create an edition of 100 objects.

The evolution of the metronome and the eye that goes with it has become an iconic image associated with Ray and the movement expressed by the metronome echoes the object’s own history with time and circumstance.

Das Lichtrequisit (1930) by László Moholy-Nagy

| Artist Name | László Moholy-Nagy (1895 – 1946) |

| Date | 1930 |

| Medium | Gelatin silver print |

| Dimensions (cm) | 24 x 18.1 |

| Where It Is Housed | J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, United States |

Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy was one the best Avant-Garde photographers and painters of the 20th century who helped propel unconventional forms in photography.

Moholy-Nagy started incorporating machine-like visuals into his paintings in the wake of his emigration from Hungary and went on to produce some of the most complex and intriguing works inspired by Russian Constructivism. Das Lichtrequisit is a kinetic mechanical creation that reiterates Moholy-Nagy’s belief in technology and its potential to assist mankind by creating artworks that advocate for the benefits of modern technology.

Moholy-Nagy started creating draft sketches of kinetic machines as early as the 1920s and by 1930, he received funding from a Berlin-based electric company to produce a light machine, which was later exhibited in Paris alongside a short film.

Number 1 (1949) by Jackson Pollock

| Artist Name | Paul Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956) |

| Date | 1949 |

| Medium | Enamel and metallic paint on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | Frame: 161.61 x 261.62 x 4.6, and image: 160.02 x 260.35 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, United States |

Abstract Expressionism was one of the most impactful Avant-Garde movements that propelled abstraction in visual art as art that was a total rejection of anything remotely identifiable yet sound in its ephemerality. Number 1 is a painting by major American Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock who skyrocketed to fame for his painting technique involving the direct pouring of paint onto a canvas, thus negating the paintbrush. Pollock relied on the natural flow and pull of gravity to dictate the visual aesthetic of his paintings.

Drip paintings such as Number 1 can be considered visual breakthroughs that disrupt the traditional view of what art should look like and what conventions should be applied to create art. Pollock’s dramatic approach has been criticized as relaying both careless abstraction and creative genius but his message is one of the latter.

Pollock conveyed a necessary critique of how art is produced and what it should look like, which raised questions about the consideration behind abstract artworks and what, if any, “planning” should look like.

Four Blackboards (1972) by Joseph Beuys

| Artist Name | Joseph Heinrich Beuys (1921 – 1986) |

| Date | 1972 |

| Medium | Chalk on blackboard |

| Dimensions (cm) | 121.6 x 91.4 x 1.8 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate collection, London, United Kingdom |

Four Blackboards was part of a performance by Joseph Beuys in 1972 called Information Action, which involved Beuys speaking for six and a half hours while answering questions. Joseph Beuys was also one of the most influential Avant-Garde artists who belonged to the Fluxus movement and advocated that anything could be art, thus broadening the scope for what could be considered or transformed into art.

Information Action was part of a group show called Seven Exhibitions hosted at the Tate Gallery. Beuys’ six-hour-long lecture was based on the power of democracy and the innate human creative capacity to shape society. The Four Blackboards contained Beuys’ conceptual schemas of his ideas and engaged with his audience in a freeform and discussion-based manner. The entrance to the show was free and garnered a huge crowd of people who interacted with the performance.

The once-off performance also highlights an issue of performance and the way that it is experienced after its debut.

A Contemporary Outlook on the Avant-Garde

Framing the Avant-Garde in Contemporary society is no easy feat since there are many emerging art styles on the rise that integrate existing and new technologies and modes of making that could potentially be categorized as Avant-Garde art. One of the most popular art critics of the Avant-Garde is Hal Foster, who describes the pattern of Avant-Garde in Contemporary history in his 1996 book Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the end of the century.

Foster suggests that the model of Avant-Garde art exists in a state of returning to the real, which means that theoretically, trends in art are rooted in materiality and social sites as opposed to previous models of the Avant-Garde in the 70s and 80s that saw art as a simulacrum and art as text. Foster argues that the idea of Avant-Garde art is not over and that perhaps the idea of radical innovation in Contemporary art serves to “trace fractures” and even “activate them”.

Contemporary Avant-Garde Artworks

With this idea of Avant-Garde art activating fractures in the art world to influence and shape the broader political, social, and environmental context of our existence, it is useful to think about what Avant-Garde art looks like in the 21st century.

Below are a few Contemporary examples of Avant-Garde artwork that offer an intriguing insight into the ways that art and science have been combined to produce exciting works.

Awaken 1 (2019) by Breakfast

| Artist Name | Breakfast collective (est. 2009) |

| Date | 2019 |

| Medium | Mirrored stainless steel, painted aluminum, custom mechanical motor system, motion tracking software, camera, and computer |

| Edition | 1/3 |

| Dimensions (cm) | 304.8 x 121.9 x 30.4 |

| Where It Is Housed | Brooklyn, New York, United States |

The Breakfast Collective is a New York-based collective that combines mechanical engineering with science and aesthetics to produce Contemporary Avant-Garde installations such as Awaken 1 that move with the viewer’s movements.

This fascinating invention marked the birth of a new medium known as Brixels, which are “motorized brick-shaped pixels” that rotate when it sense movement. This interactive artwork can be considered Avant-Garde since it provides a new technological medium that provides a diverse range of visual aesthetics that one can view and alter the artwork itself.

Brixels thus engages the viewer and space and invites the public to take on the role of the artist and “draw” what they wish to see via robotics.

In Love With The World (2021) by Anicka Yi

| Artist Name | Anicka Yi (1971 – Present) |

| Date | 2021 |

| Medium | Installation |

| Dimensions (cm) | Information unavailable |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate collection, London, United Kingdom |

Blurring the boundaries between science and art, Anicka Yi in partnership with Hyundai, experimented with the connections between biology and technology, which posed questions about the future of artificial intelligence. In Love With The World is an installation of floating machines called aerobes inspired by mushrooms and ocean life forms. Each vehicle follows a unique flight path programmed by a variety of options available in their software. Yi’s exploration of the relationships between art, technology, and biology makes evident the ways that machines and artificial intelligence can be used to help the public reimagine alternative uses of technology in the real world.

The Avant-Garde poses some challenging questions that shed light on the way that we perceive Modern art and how an artist could think about innovation and originality when creating “Avant-Garde” artwork. It is important to question what the term Avant-Garde means in a Contemporary era, as well as how one can approach originality given that much has been “done” in the art world. With an ever-expanding growth of technological and scientific innovation, it is important to keep questioning the role of the artist in accessible knowledge production and sharing.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Avant-Garde?

Avant-Garde is often referenced as a 20th-century umbrella movement that encompassed art movements from different periods that were classified as either unconventional or experimental and which differed from existing cultural, social, and political norms. Avant-Garde can be understood in terms of aesthetic innovation accompanied by a level of unacceptability.

What Were the Most Influential Avant-Garde Art Movements of the 20th Century?

The most influential Avant-Garde art movements of the 20th century included Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Minimalism, and Abstract Expressionism.

What Is the Difference Between Modernism and Avant-Garde Art?

The difference between art under Modernism and Avant-Garde art is that Modernism aimed to prioritize the celebration of modern society without drawing connections back to life, while art classified as Avant-Garde made use of innovative ideas to reinforce or promote radical social or political change.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Avant-Garde Art – Pushing the Boundaries of Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 9, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/avant-garde-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 9 October). Avant-Garde Art – Pushing the Boundaries of Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/avant-garde-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Avant-Garde Art – Pushing the Boundaries of Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 9, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/avant-garde-art/.