“Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Discover Duchamp’s Urinal

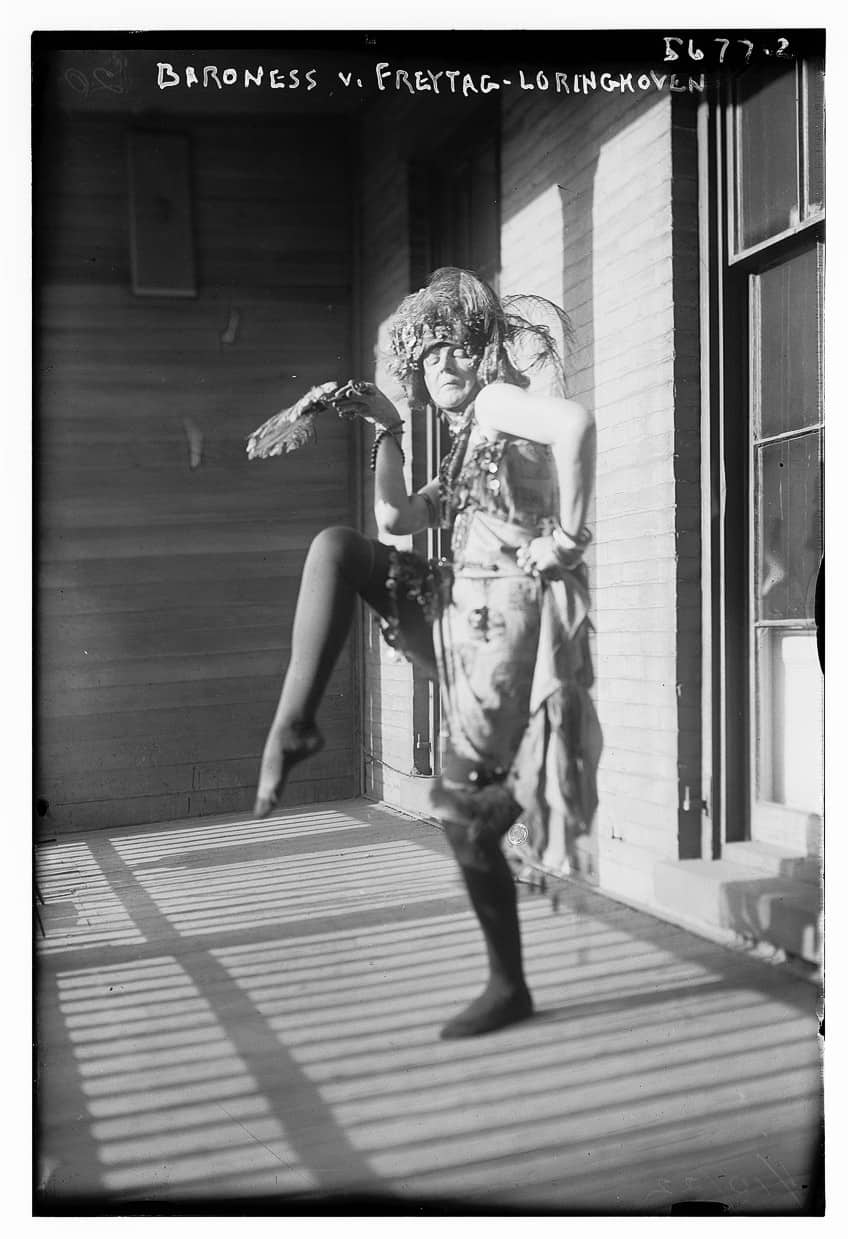

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp kickstarted the conceptual art movement in the early-1900s. He created this urinal art over a couple of years and with it altered the course of art history forever. The Fountain sculpture is considered one of Marcel Duchamp’s most famous works. To most people, the fuss about Duchamp’s Fountain challenges their ideas of beauty and art. Besides the scandal it created in the art world at the time of its creation, the artwork holds a further secret named, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Let us look at what made this urinal art such an impactful sculpture.

Contents

Artist Abstract of Marcel Duchamp

| Date of Birth | 28 July 1887 |

| Date of Death | 2 October 1968 |

| Country of Birth | France |

| Associated Art Movements | Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, Conceptual art |

| Art Style | Conceptual Art |

| Mediums Used | Painting, sculpture, collage, short films, body art, found objects |

| Dominant Themes | Erotica, humor |

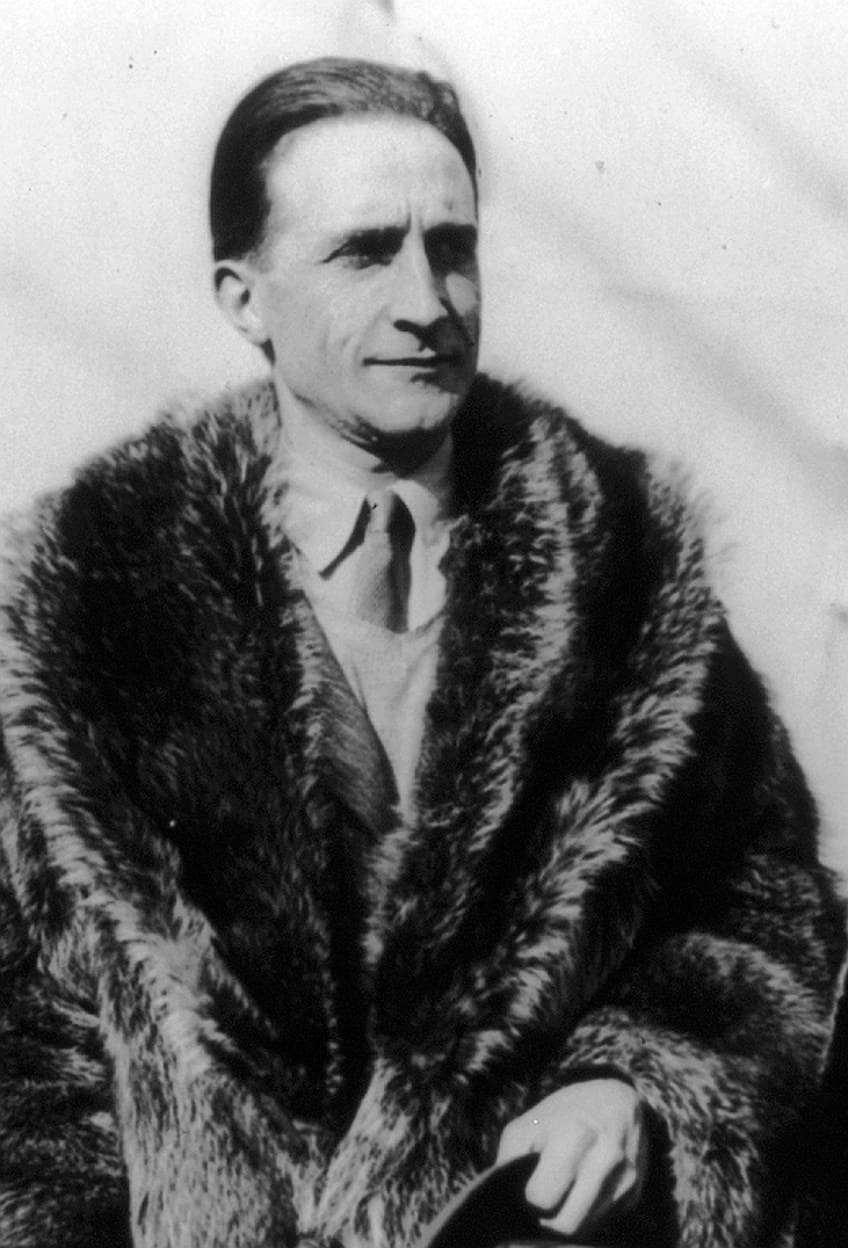

Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) became a catalyst for the conceptual art movement, which only really began to be a formal art movement from the 1960s on. When looking back through art history, his influence is so impressive that one might argue he is one of the most important artists to have lived.

This artist, however, had his origins in multiple other art movements before dabbling in conceptual art.

In this section, which looks at the artist that created Fountain (1917), it is important to flag that the story about the creator of the Fountain sculpture is somewhat contested. Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874 – 1927) is often argued to be the actual mastermind behind this urinal art. In a later section of this article, we will look at this artist’s relationship with Duchamp and her influence and role in the creation of the Fountain sculpture.

Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville, Normandy, in 1887. His father was a notary and his older brothers were a painter, Jacques Villon, and a Cubist sculptor, Raymond Duchamp-Villon. From 1904 to 1905 Duchamp studied at the Académie Julian where he created figure paintings inspired by Matisse and Fauvism. His painting developed into a personal interpretation of Cubism in 1911. The paintings he created at this time were marked by mechanical and instinctual forms, earthy colors, and the capturing of movement, which made these paintings Futurist as well as Cubist paintings.

After a scandal in Paris around one such painting (see the next section), Duchamp moved his practice to New York.

He did not continue to paint much more after 1912, as his focus shifted in 1913 to a revolutionary new form of art, his ‘readymade’ concept. The art piece that made this new form of art famous was Fountain. And the event that led to its fame was the censorship of it by the directors of the Society of Independent Artists (a society that Duchamp helped found and promote).

Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) in Context

| Artist | Marcel Duchamp |

| Date | 1917 |

| Materials | Found glazed ceramic urinal, signed with black paint |

| Art movement | Dada |

| Series | Readymades of Marcel Duchamp |

| Dimensions | 61 x 36 x 48 cm |

| Location | The original is lost; a replica is housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art |

At the beginning of the 20th century, the avant-garde art movement’s ideas were saturating Europe and spreading to America. Marcel Duchamp was at the forefront of changing the meaning of art forever – the motto often associated with his career being: “art as anti-art.”

The widely accepted story about Fountain is that the public did not know Duchamp was the creator.

He hid his involvement with the submission of this urinal art to the first open exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. Some critics speculate that the Fountain debacle was a test on Duchamp’s part to see if his fellow board members would honor the Society’s manifesto, which he helped write.

The First Controversy: The Salon des Indépendants in Paris

The theory is that the reason why he created such a controversial work could be linked to his experience in 1912 with the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. Duchamp formed part of this group and submitted his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2 (1912) to the Salon. This was an important painting to Duchamp as it pushed his unique style of Cubism and Futurism combined to new levels. It would prove to be very important to the history of art as well.

The committee was shocked by the subject matter and the title of this painting and did not want to be associated with it.

They included the painting in the catalog but asked Duchamp’s brothers (members and Cubists themselves) to ask him to withdraw it from the exhibition. A few days before the show opened Duchamp withdrew his entry but did not forgive the other members of the group for censoring another artist’s work.

He saw this as a deep betrayal and, therefore, his actions towards the new American Society he joined can be seen as testing their tolerance for artistic freedom and expressions of new concepts of art.

The Second Controversy: Duchamp’s First American Exhibition

Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2 (1912) was also met with shock in America at the Armory show in 1913. However, this exposure paved the way for his success as his name was spreading through this controversy. The painting became famous and eventually sold, making life in America possible for Duchamp.

It also kickstarted his career there within the Society of Independent Artists.

Duchamp moved from Paris to New York in 1915. He started planning the society’s inaugural exhibition and was part of the hanging committee. He thought this to be the right moment to test just how open-minded the members of the society were when it came to breaking the boundaries around the art academy’s traditions.

The society failed him, and with their actions added to a whole new movement in Modern art.

Analysis of Fountain by Marcel Duchamp

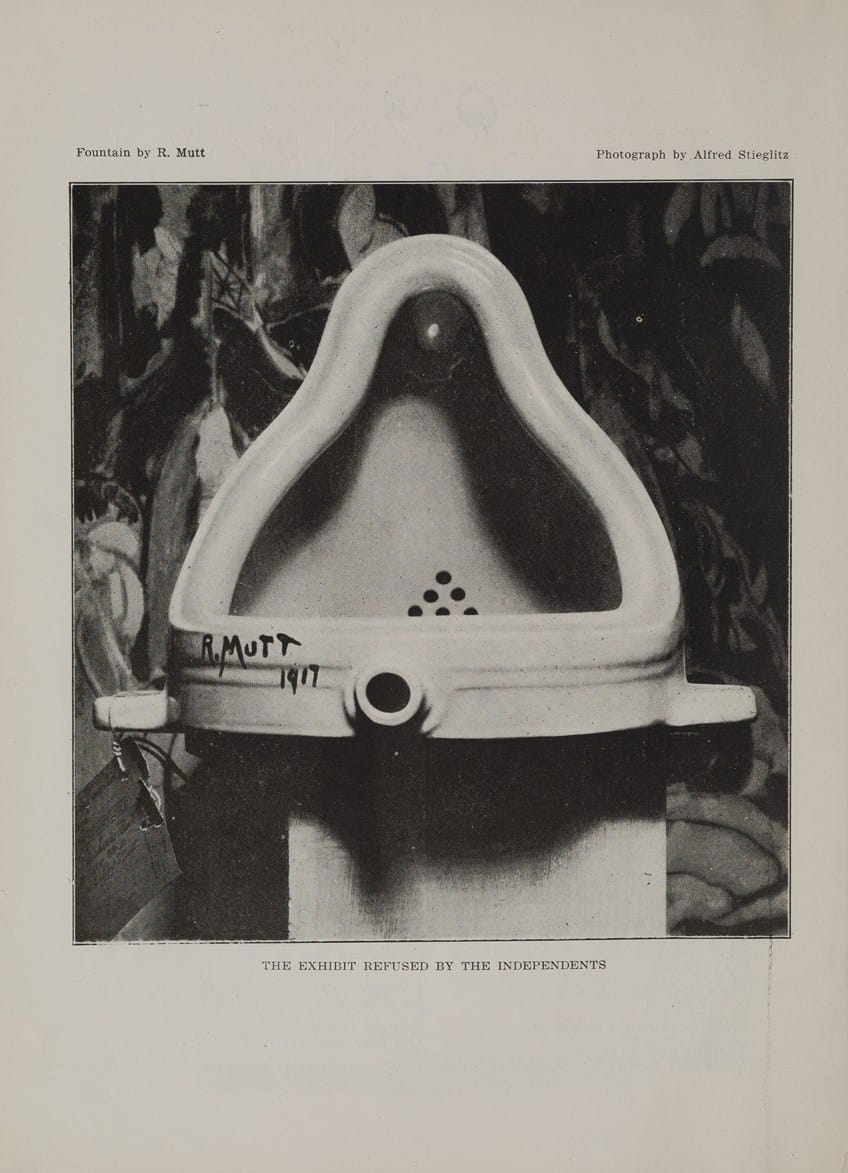

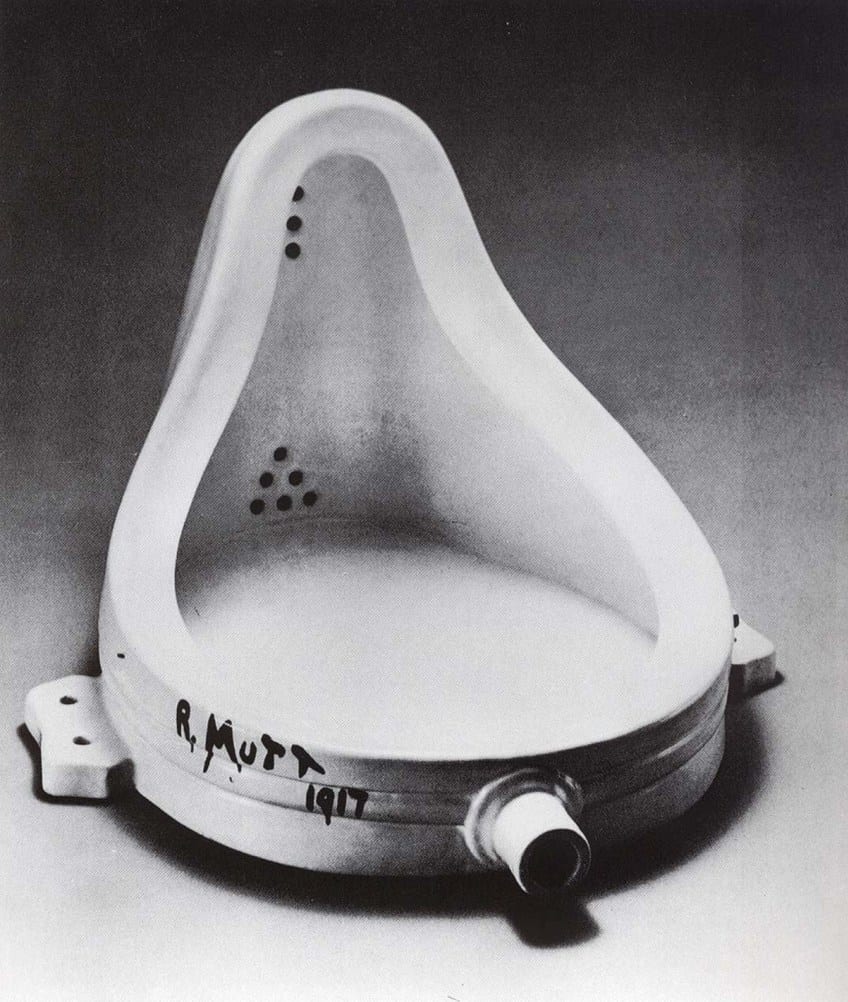

Fountain, created in 1917, consisted of a normal urinal. It was glazed with white ceramic paint. Nowadays the replicas are commonly presented on a pedestal, flat on their back in exhibition rather than upright. It was signed and dated “R. Mutt 1917”. The original was lost after being photographed in 1917 by Alfred Stieglitz (1877 – 1946), a famous gallery owner and photographer.

This photograph, which was taken around 19 April 1917, has become the form in which this artwork has populated the world.

It is the only visual record of the original Fountain’s existence. Stieglitz proudly wrote that his image “is really quite a wonder.” He said that everyone he showed it to thought it was beautiful and that it had something oriental to it. He explained that it looked to him like a cross between a veiled woman and a Buddha.

The replica of Fountain created in 1950 is now housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Tate Modern also has a replica of Fountain, which was created in 1964. This version was made out of glazed earthenware and painted to look like the original porcelain. The signature was also replicated on the copies in black paint.

The Conceptual Reasoning Behind the Fountain Sculpture

Fountain has been seen as an outstanding example of Duchamp’s ‘readymade’ art pieces. Alongside other works by him like the Bottle Rack (1914), he created a new genre of art that allowed artists to use mundane manufactured objects and assign artistic meaning to them. It was one of the first art pieces that had a concept at its center instead of the actual physicality of the artwork.

In other words, Duchamp’s statement about the urinal art was more important than the physical urinal itself. It became a symbol of what art would become – boundless – of its indefinable future.

The message Duchamp was trying to relay was about the art world itself, so he was turning the lens inward towards the Society that was vetting what was and was not considered art. This self-conscious art piece was successful in reflecting the society’s biased views and closed-minded worries. The fact that Fountain became one of the most popular works of art history makes it a very successful conceptual art piece. What Duchamp managed to say with Fountain, is that when an artist assigns artistic value to an object there is very little the academy, industry, or whoever is in power can do to discount it.

This ordinary object, placed on a pedestal in a gallery, therefore, empowered artists as the ones that decide what is and is not art. It also allowed artists to incorporate absolutely everything from the visual world into the category of art. Thus, art after Fountain permanently broke away from the restraints of classically academic art. Duchamp’s concept was that even the act of thinking of a urinal as art is creative.

Submitting this artwork to the specific exhibition he did was also very important because Duchamp was essentially arguing that if the world does not allow anyone to be an artist, then it is time for it to consider that anything could be art.

Most of Duchamp’s work always dealt with the nature of art. He loved discussing the possibilities of what artists can do, and Fountain was meant to do the same. He wanted to bring humor into art and open art up to be absolute and without borders.

Process Behind the Duchamp Urinal

In later years after the creation of Fountain and its subsequent loss, Duchamp reflected that the idea behind this piece came out of a discussion in New York with the artist Joseph Stella (1877–1946) and art collector Walter Arensberg (1878–1954). After they decided on trying this groundbreaking art piece submission, Duchamp bought a urinal from a sanitary ware company.

He arranged for it to be submitted to the newly founded Society of Independent Artists under the name “R. Mutt”.

Blindman published a slightly cropped version of the photograph by Stieglitz after the urinal was lost. The article that accompanied it was anonymous and openly defended the artwork, further cementing its influence on the art world.

The Reception of Duchamp’s Fountain

On April 10th, 1917, the Society of Independent Artists opened its first exhibition at the Grand Central Palace in New York City. The idea was that there would be no rules. Everyone that paid the $6 entry fee would be allowed to show their work. There were no jury and no prizes. Duchamp himself added to this new exhibition structure by suggesting that the entries be exhibited alphabetically instead of curated according to someone’s specific preference.

This exhibition, and those to follow yearly, were intended to be different from the elitist academic salons and proudly stated that they were completely open to anyone regardless of their background.

The Third Controversy: The Society of Independent Artists in New York

When Duchamp submitted Fountain, it rocked the committee to its core. Never before had anyone considered a piece of sanitary ware as art. The committee was shocked and thought that exhibiting an artwork connected to bodily waste was inappropriate. One can further deduce from their decision to exclude it that the fact that women would have seen it in the exhibition was also too controversial for the directors.

The ten directors voted on behalf of the Society’s board on whether Fountain should be included or not while the exhibition was being installed. They narrowly decided to exclude it, to which Arensberg and Duchamp resigned from the board in protest.

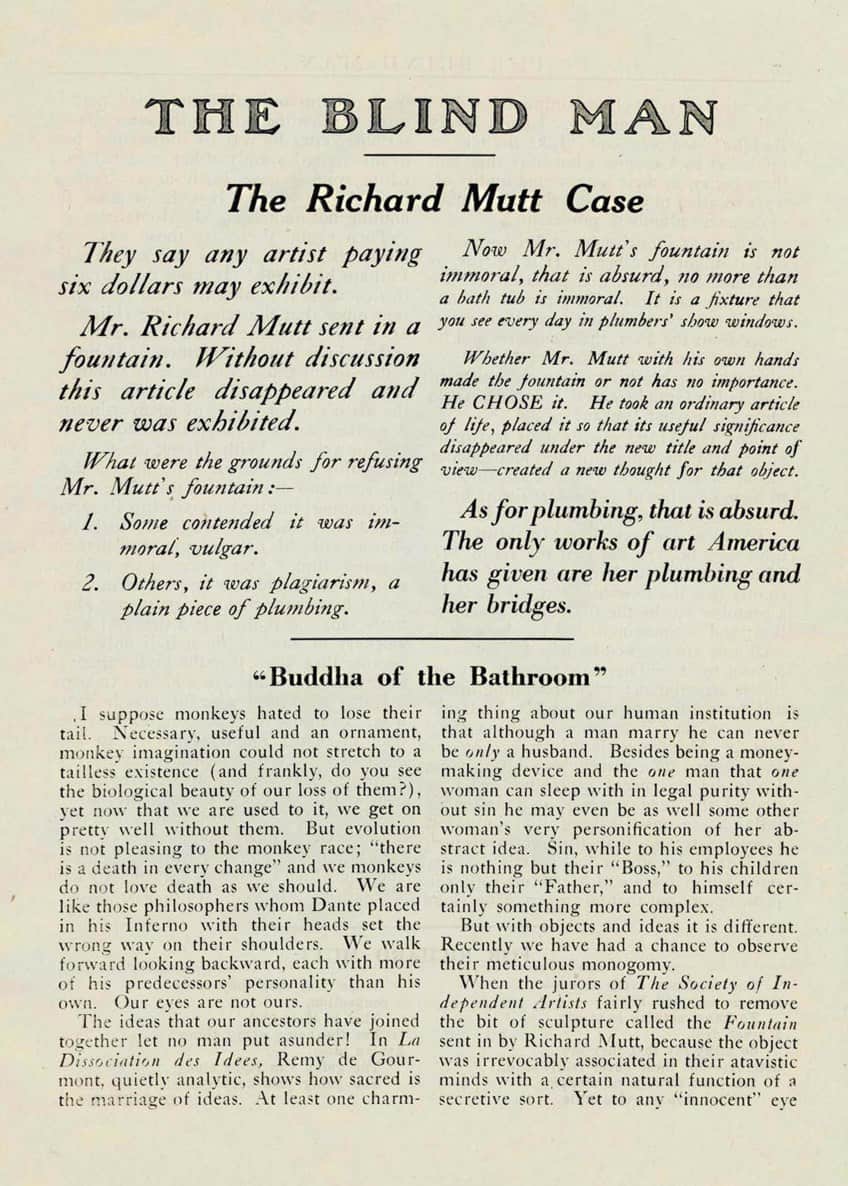

Many important people in the art world were invested in the idea of a democratic, uncurated exhibition. New York was quickly surpassing Paris as the center of contemporary art. There was, therefore, a lot at stake in the directors defending such a specific conception of art. After a day or so of the exhibition’s opening Duchamp found his artwork stored in the exhibition hall behind a partition. He had it photographed and this famous photograph was published in the first Dada periodical, the Blindman.

The edition in which it was published stated that Fountain by Mr. Mutt is “not immoral”. It stated that it is absurd to believe it is immoral as we would then have to believe a bathtub is also immoral. It went further to explain the pivotal and revolutionary quality of this readymade by arguing that it is not important whether the artist made it with his own hands or not, but that the artist chose it and that is all that matters.

The article further explained that by changing its place and position in the world, making its practical use irrelevant, “Mr. Mutt” created a new meaning for this everyday object – a new meaning that would not have been possible if he did not make it an artwork.

Years later, Beatrice Wood admitted to having written the article and Marcel Duchamp stated that he agrees with everything said in it. The board of the Society responded to their decision and the resignation of Duchamp and Arensberg by stating that Fountain is a very useful object – in its right place – but that that place is not in an exhibition and that it certainly is not a work of art.

The Influence of Urinal Art

The first important impact Fountain had is that it caused outrage in an exhibition that was supposed to be jury free and open to all. Duchamp exposed the controlling powers of the art world at the time but this result has affected all art since. The question, “who gets to decide what is and is not art?” has motivated creatives to push the boundaries of the definition of art endlessly. This has given us a rich variety of art, including sound art, performance art, and many more we are used to today.

Furthermore, the use of an ordinary object as art opened up the possibilities of what artists can create as well as made art more accessible to everyone.

People all around the world can now use any objects in their art and the possibilities became infinite. Another massive influence that Fountain had on the world of art is that the message or concept behind an art piece became equally as important as its materiality.

It also made it possible for the subject matter of an artwork to be a statement not at all intuitive to the visual qualities of the work itself.

It made the context within which it is created and shown vital to understanding its meaning. After Duchamp, art involved humor when the artist felt like it. His art gave the artists that followed the opportunity to be more playful, to not take themselves so seriously. Aesthetics was downgraded from being the most important aspect of art. Duchamp shifted this defining aspect of art to the creative act – the creative thought or idea became the art.

The Fourth Controversy: Fountain’s Secret

Similar to the influence Lee Krasner had on Jackson Pollock, and Simone de Beauvoir on Jean-Paul Sartre, the influence the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven had on Marcel Duchamp has largely been ignored throughout art history. Historians and art collectors have argued a lot about her actual involvement in the creation of Fountain, with some finding proof that she found it, signed it, and submitted it.

The Proof

This German poet and artist was very close to Marcel in the art scene in New York. One piece of evidence found by researchers, potentially proving her as the creator of Fountain, is a letter Duchamp wrote his sister Susanne. In it he recounts the exact tale of one of his female friends finding, signing, and submitting a piece of plumbing to the Society of Independent Artists’ first-ever exhibition.

Furthermore, R Mutt was determined to have been an artist that lived in Philadelphia, which is where the baroness was living at the time.

Of course, this story is contested as the urinal was lost and what makes it more complicated is that Duchamp only claimed the work as his own in 1950. This was long after the death of the baroness and four years after the death of the photographer Stieglitz. Even though André Breton accredit Fountain to Duchamp in 1935 it was only 25 years later that he claimed it and started issuing replicas.

Duchamp stated that he had bought the urinal from JL Mott Ironworks Company, and changed Mott to Mutt. However, this company did not sell the model urinal in the photograph. Von Freytag-Loringhoven on the other hand collected pipes, drains, and spouts. She made regular references to plumbing in her poetry. The handwriting on the urinal matched that in her poems. These are only a few historical clues that historians have found.

Many creatives throughout the years have reiterated this evidence and yet, the world holds on to Duchamp being the mastermind behind it.

One reason might be that the history of art notoriously praises and recognizes male artists much easier than female artists. Some historians even believe that the fame the urinal reached would not have happened if Von Freytag-Loringhoven was recognized as the artist from the beginning.

Fountain created a lot of scandal at the time it was created. Even nowadays we are not entirely sure who the author of the art piece was and historians and art enthusiasts fight about whether a man or a woman created it. The fact is, that this art piece was created at the right time and released in the perfect way for it to have changed our understanding and practice of art forever. It even started an art movement so popular today that almost all art is interpreted through its lens: conceptual art.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Created Fountain (1917)?

Marcel Duchamp is famously believed to have created the urinal art called Fountain. He signed it under an alias, R. Mutt because he was part of the Society of Independent Artists board to whose first exhibition he submitted the piece. Recently, there has been speculation that Fountain was actually created by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Was the Duchamp Urinal Made by Hand?

If you follow the typical story of how Fountain came to be, then Marcel Duchamp did not make Fountain by hand. He ordered it from a sanitary ware company and signed it in a dark paint. It formed part of his series of readymade sculptures that revolutionized what we understand as art today.

Which Art Movement Was Fountain by Marcel Duchamp Part Of?

Fountain (1917) is often ascribed to the Dadaist movement, as Marcel Duchamp was later made the center of this movement, having acquired the most fame. However, Duchamp had actually withdrawn from the original European Dadaist group when his brothers had asked him to remove the painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2 (1912) from an exhibition. Fountain sparked the conceptual art movement, which kicked off in full force in the 1960s.

Nicolene Burger, a South African multimedia artist and creative consultant, specializes in oil painting and performance art. She earned her BA in Visual Arts from Stellenbosch University in 2017. Nicolene’s artistic journey includes exhibitions in South Korea, participation in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, and solo exhibitions. She is currently pursuing a practice-based master’s degree in theater and performance. Nicolene focuses on fostering sustainable creative practices and offers coaching sessions for fellow artists, emphasizing the profound communicative power of art for healing and connection. Nicolene writes blog posts on art history for artfilemagazine with a focus on famous artists and contemporary art.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and about us.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, ““Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Discover Duchamp’s Urinal.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 10, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/fountain-by-marcel-duchamp/

Burger, N. (2022, 10 November). “Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Discover Duchamp’s Urinal. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/fountain-by-marcel-duchamp/

Burger, Nicolene. ““Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Discover Duchamp’s Urinal.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 10, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/fountain-by-marcel-duchamp/.