Black Death Art – Artistic Legacy of the Bubonic Plague

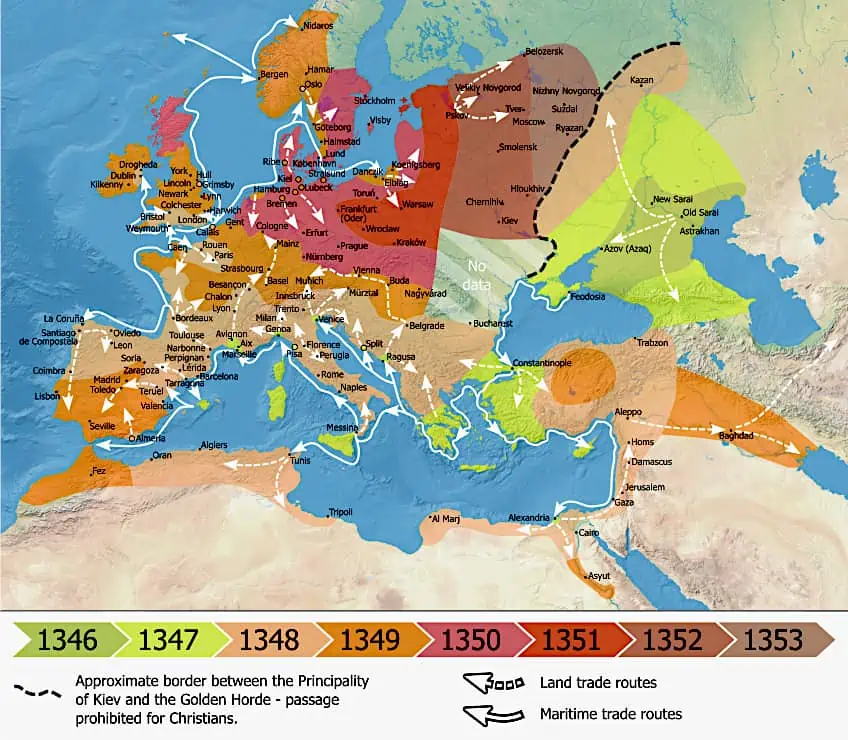

The Black Death, also known as the Black Plague or Medieval Bubonic Plague, played a significant role in shaping European history. It killed anywhere from 25 to 200 million people across Europe, starting somewhere between 1346 and 1348 and raging into the early 1350’s. Wiping out a third, or even by some estimates, as much as half of Europe’s population, it is not surprising that this unprecedented disaster became an integral part of medieval culture. Death was now a common theme in literature and art. And while the plague profoundly altered the generation that lived through this devastation, its effects would linger for centuries to come.

The Black Plague

While it is generally accepted that contemporary accounts provide the most reliable insight into people’s experiences of the Bubonic Plague, the plague left an indelible mark on the art and culture of Medieval Europe. The Black Death naturally influenced many works, from poetry to art. In such a dark time, it was natural that writers and artists felt the need to put their struggles and trauma into their work. This can be seen in the written works of Boccaccio, Chaucer, and Petrarch, and in the artworks of artists like Holbein.

Artists have frequently attempted to make sense of the damage and despair brought on by plagues as their communities battled the plague. Artists’ perceptions of the atrocities they saw had evolved significantly over time, but what hadn’t changed was their aim to convey the essence of an epidemic. So, What was the state of art during the Black Death’s devastation of Europe in the 14th century, and how was this time period portrayed in Medieval art?

Firstly, a brief explanation of the Bubonic Plague before we get into the way it influenced art. During the 14th century or the Middle Ages, Asia and Europe were devastated by the Bubonic Plague, sometimes known as the Black Death. The Yersinia pestis bacteria caused the infection that led to the Black Plague. The disease was spread by fleas who had contracted the virus from other hosts such as rats.

New trade routes between Europe and Asia opened up in the 14th century, allowing fleas and rats—who were affected by the fleas—easy access to countless villages and cities. The Bubonic Plague spread swiftly because of a lack of scientific understanding and hygiene, and within a short period of time twenty million people in Europe died from the illness.

The typical symptoms of the Bubonic plague included fever, chills, and vomiting. However, the victims were often covered in boils that would bleed and excrete puss. It didn’t take long for the victim to pass away after experiencing all of these symptoms; typically two to seven days following diagnosis.

It is estimated that between one-third up to one half of Europe’s population was killed by the plague.

This naturally created a sense of hopelessness and dread within culture, and this was naturally expressed through literature and art for centuries to come, such as Shakespeare with his play, King Lear (1606).

As the Medieval period was a time of mass illiteracy, powerful visual imagery and appealing narratives were developed to capture the attention of audiences and convey the magnitude of God’s ability to punish disobedience. In addition to being considered God’s retribution for sin, dying from the plague was also interpreted as a portent of eternal misery in the world to come.

As a way to convey their complicated emotions and try to make sense of the unanticipated harm caused by the Medieval Bubonic Plague, Black Plague artists repeatedly attempted to do so through their work. While the artists’ depictions of the tragedies they witnessed have changed significantly over time, their attempt to capture the spirit of an epidemic has remained constant.

Artists have depicted plagues and other epidemics for a large portion of history from the viewpoint of the intensely religious environment in which they lived. The first time the Black Death appeared in European art, it reflected a society wholly unprepared for the disease’s fury which was widely believed to be divine punishment for sin.

In the centuries that followed, the role of the artist changed. Their goal was to create a sense of compassion in plague victims so they would connect with Christianity and appreciate and honor Christ. Strategies to safeguard and comfort affected societies included encouraging strong emotions and more strength in the fight against the pandemic.

Through their work, these artists conveyed ideas about the transience of life, the connection to the supernatural, and the responsibility of caregivers. When few people could read, beautiful pictures with intriguing stories were created to draw audiences and astound them with God’s ability to punish sin with diseases. Death from the plague was seen as both God’s retribution for sin and a warning that the victim would struggle for the rest of their lives in the following world. Historians have argued that this was a method from the Church to re-establish control in a devastating time.

The Black Death powerfully reinforced realism in art. The promise of heaven felt unrealistic, and the fear of damnation grew dreadfully real. Both the wealthy and the poor felt a sense of urgency to secure their salvation. Rich and educated people carefully considered having a bona mors (a good death) or, if that was not possible, at least a lavish funeral and tomb, after reading about the Day of Judgment.

A Brief History of Black Plague Art

While Black Death Art generally captured the Bubonic Plague of Medieval times, plagues were often depicted in previous ages. This can be seen with Ill Morbetto, an example of plague art with source material predating the Black Death. The work is based on a passage from the Aeneid, a Latin epic poem, written by Roman poet Virgil between 29 to 19 BCE, which depicts the hero Aeneas’ escape from Troy to Italy following the Trojan War.

As this literary work predates the Medieval age by several centuries, it could be argued that this is one of the earlier depictions of plague in Western culture, with Ill Morbetto visually depicting the writing in the 1500s CE.

Ill Morbetto (The Plague) (1512 – 1513 CE) by Marcantonio Raimondi

| Artist | Marcantonio Raimondi (1480 – 1534 CE) |

| Date | 1512 – 1513 CE |

| Medium | Engraving |

| Current location | National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., United States |

The engraving of Il Morbetto (The Plague), by Marcantonio Raimondi in the early 16th century, based on a piece by Raphael, marked a significant advancement in plague art. Dr. Sheila Barker, a US plague art historian, claims that the significance of this small artwork lies in its emphasis on a small group of people who may be identified by their age and gender.

As a result of these characters’ humanization, we are compelled to sympathize with their plight.

We witness the sick being treated with such tenderness that we are moved to take action to ease their suffering. Here, a work of art has the power to persuade us to do something we might be reluctant to do: care for sick and infectious souls.

This shift in plague art happened alongside the evolving understanding of public health. Everyone in society, not just the wealthy who could flee to their country estates, ought to be safeguarded. In order to protect themselves, doctors were to be fined if they left the city. With the Catholic Church’s tighter alignment with a public-health agenda in the 17th and 18th centuries, this empathy concept was further developed.

Churches and monasteries started showcasing plague art. Now, the disease was connected to Christ and its victims. The goal of this identification, according to Dr. Barker, was “to persuade the friars to overcome their terror of the rotten stench of the dying body and the vastness of death by learning to love the contagious plague victims.”

People who provided care for the victims may have made self-sacrificing decisions, elevating them by portraying them in a saintly light. The Black Plague was depicted in several ways in art, most of which followed the general themes of death, religion, sin, and the medieval concepts of medicine.

Depictions of the Plague in Art

In the artistic depictions of the Black Plague, the most common themes represented were death, religion, and medicine. Death would naturally be the most common theme, as the Plague killed an estimate of 25 million people across Europe. Religion became a common theme due to the Church’s response to the Plague, which included the assumption that the deadly disease was a punishment from God.

The theme of medicine emerged as European society desperately searched for cures and treatments for the Plague.

Death

Skeletons and death were a common theme during the Black Death. Memento Mori, which is Latin for “remember you must die,” is the name given to these types of works that are devoted to death. Memento Mori artworks serve as a constant reminder of impending death. These pieces were made as still-lifes with skeletal figures, smoldering candles, withered flowers, and timepieces. The 17th century saw the greatest popularity for Memento Mori artworks.

Tournai Citizens Burying the Dead during the Black Death (1347 – 1352 CE) by Pierart dou Tielt

| Artist | Pierart dou Tielt (Dates Unknown) |

| Date | 1347 – 1352 AD |

| Medium | Miniature from a folio |

| Current Location | Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium |

An example of the depiction of death in these artworks would be Tournai Citizens Burying the Dead during the Black Death by Pierart dou Tielt. This Black Death artwork, by an unknown artist, shows a mass grave in the Belgian town of Tournai where Black Death victims were interred in mass graves. In a very narrow frame, we witness fifteen individuals carrying the coffins of their loved ones. The faces of the people are all distinct and filled with emotion, which is unusual for Medieval painting at the time (naturalism didn’t gain popularity until a century later). If one were to look closer, one would see this.

This work clearly displays fear and loss, drawing inspiration from how people felt at the time. This picture is a close-up of a miniature found in the abbot of the Belgian monastery of St. Martin the Righteous, called The Chronicles of Gilles Li Muisis.

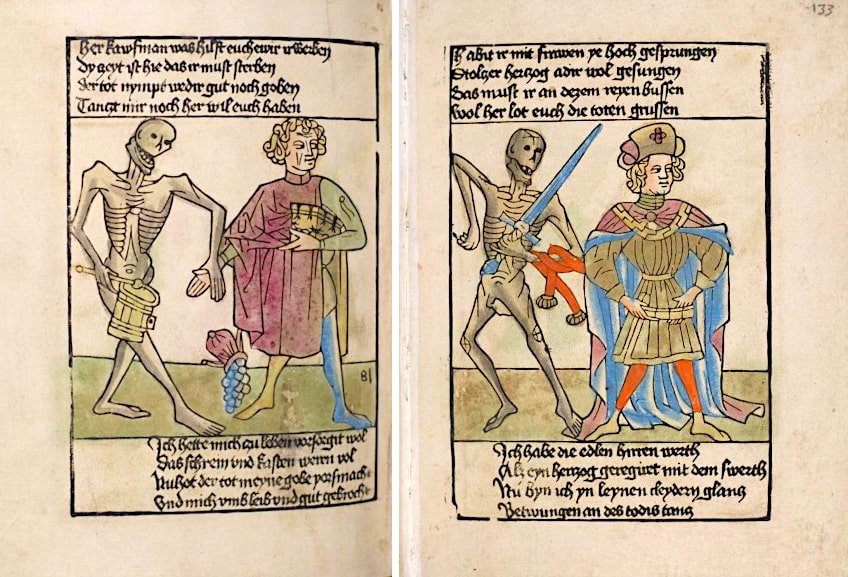

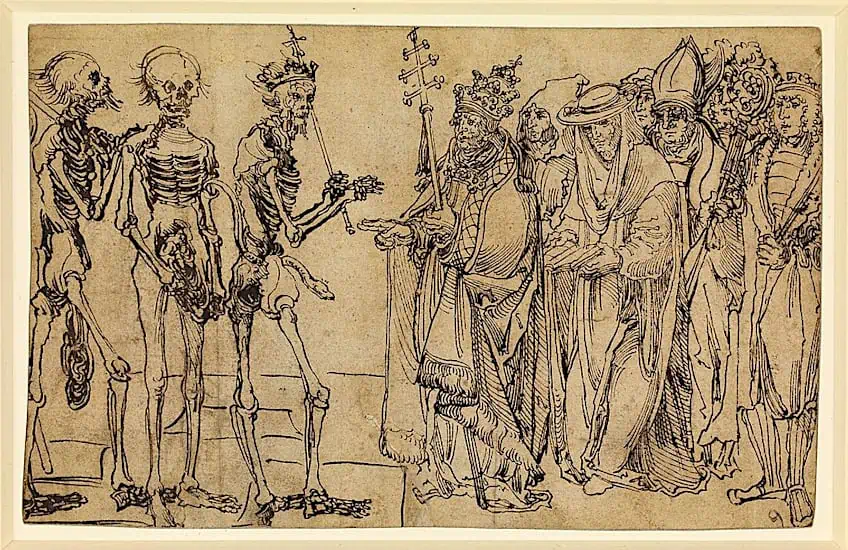

Similarly, the Danse Macabre, sometimes known as the Dance of the Dead, was a popular and common motif with its origins in Medieval art. Of course, that doesn’t sound amusing today, but in the fourteenth century, this was considered tongue-in-cheek.

It is further evidenced by dancing with skeletons to please Death herself that performing arts such as dancing didn’t stop because people were dying. Before they passed away where they were, people wanted a means to have fun and laugh. This can be seen in works like The Triumph of Death with the Dance of Death, (15th Century) by Giacomo Borlone de Burchis.

In this piece, Burchis shows people from various walks of life dancing alongside skeletons for the Queen of Death, who is depicted holding two scrolls at the top of the piece. Two skeleton thugs with bows and an arquebus are standing next to her (which was an early prototype for the musket). No male is immune to this illness, as evidenced by the Queen’s position atop an open coffin containing the bodies of an emperor and a pope. As they offer her presents and money, the people below the Queen of Death beg for mercy.

The Queen of Death, however, is not the Queen of material things like goods, food, or money, instead, she is the Queen of Lives and will take what she pleases. This motif remined popular in the centuries to come, with examples of the Dance of Death widely reproduced and distributed with the invention of printing.

The Triumph of Death (1562 CE) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

| Artist | Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525/1530–1569 CE) |

| Date | 1562 CE |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Current Location | National Museum of Prado, Madrid, Spain |

Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted a representation of the struggle between life and death many years after the initial Black Death, The Triumph of Death. The motif of this Bubonic Plague painting, also called death triumphing over humanity, was a common theme throughout the Black Death’s dreadful era. “The Triumph of Death” is based on Petrarch’s poem “The Triumph of Fame,” (1502-1504 CE) which explored the feelings of warriors who had returned home from battle victorious. Skeletons degrade the deceased by excavating their tombs and drag people to their deaths.

The scene is graphic and depicts the unfavorable reality that sickness brings to a civilization, completely eliminating all prospects for existence.

Religion

When the Black Death was making its way through entire towns throughout Europe and Asia at the time this work was created, people thought God was responsible for the epidemic.

By emphasizing that people wouldn’t become ill if they prayed, attended church, and removed sin from their life, the Church seized this opportunity to convert more people and gain some sense of political control.

Naturally, this is untrue, but it didn’t stop people from attending church, giving the church an even greater influence than before.

Madonna of Humility (1345 – 1350 CE) by Guariento di Arpo

| Artist | Guariento di Arpo (1310 – 1370 CE) |

| Date | 1345 – 1350 CE |

| Medium | Tempera and gold on panel |

| Current Location | Getty Center, Los Angeles, United States |

When looking at an artwork like Madonna of Humility by Guariento di Arpo, we see an example of art made during the time of the bubonic plague that does not necessarily depict the plague itself, but rather depicts a deity to whom victims should look for comfort and health. The title, “Madonna of Humility”, alludes to the Virgin Mary as a maternal figure for those who follow Christianity.

The Virgin Mary was very rarely absent from Medieval art. All around the world, Christian churches, and altars have representations of the mother of Jesus Christ, which are the essential essence of religious art. Between 1345 and 1350, the Italian painter Guariento di Arpo created Madonna of Humility.

Mary is shown nursing the Christ child while she is seated. She has a golden crown with jewels on her head, and above her is a depiction of God, the Father, blessing the Mother and Child.

Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (1497 – 1499 CE) by Josse Lieferinxe

| Artist | Josse Lieferinxe (1493 – 1503/08 CE) |

| Date | 1497 – 1499 CE |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Current Location | The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, United States |

Similarly, Saints were often depicted in these works as well, such as with Josse Lieferinxe’s Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken. Although this work was created during the Renaissance, the piece depicts the time of the Black Plague, specifically when a community in Pavia, Italy was devastated by a plague in the seventh century. Years before the infamous Black Death, a lesser pandemic took place, and St. Sebastian is shown praying with God to spare the sick and dying.

A famous saint in medieval art, St. Sebastian was portrayed in similar works found in the chapel of Saint-Crepin-Ibouvillers in France. During the Black Death, many people prayed to St. Sebastian with the aim of eliminating the disease from daily life.

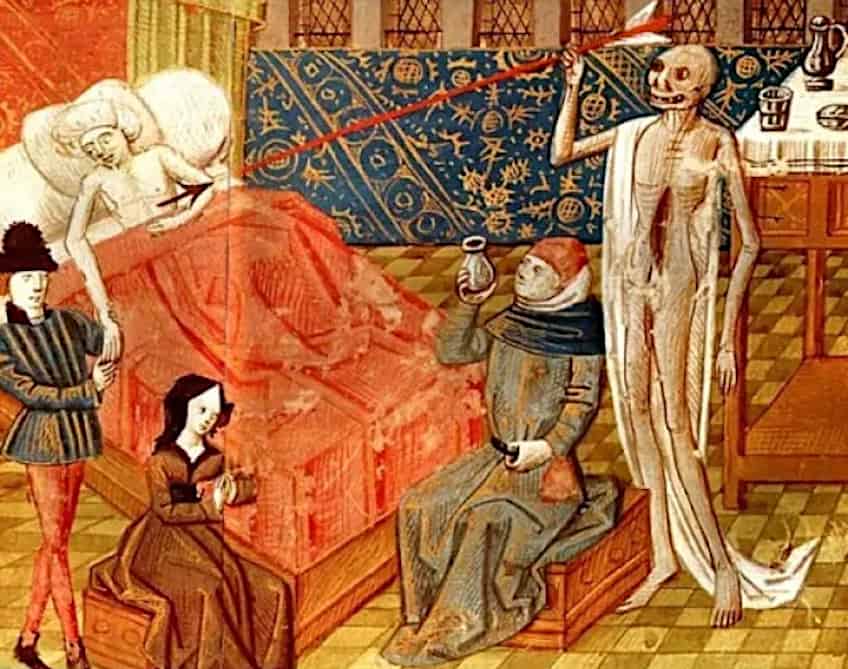

Another common motif was imagery of devils or demons attacking the plague victims. In instances like this, these images were meant to portray the belief that the devil was hired by God to punish people for their transgressions. Medieval people who saw these images would be frightened by the winged beings. These images served as a warning about both the end of the world and the demise of humanity.

Medicine

Medicine during the Medieval Era was obviously not as advanced as we have today, so medical professionals of the time were not at all prepared for the highly contagious, terminal disease. Most Plague doctors based their practices on the medical theories and techniques of the classic scholars, such as Aristotle and Hippocrates.

As the Medieval Bubonic Plague spread during a time where the Church was the primary source of information, many believed the way to prevent catching the plague was murder in the name of God. Christians held the belief that the disease’s spread was the fault of the Jewish people. They believed that God was enraged by the Jewish people’s rejection of Jesus as the Messiah, and sent the Black Death as punishment.

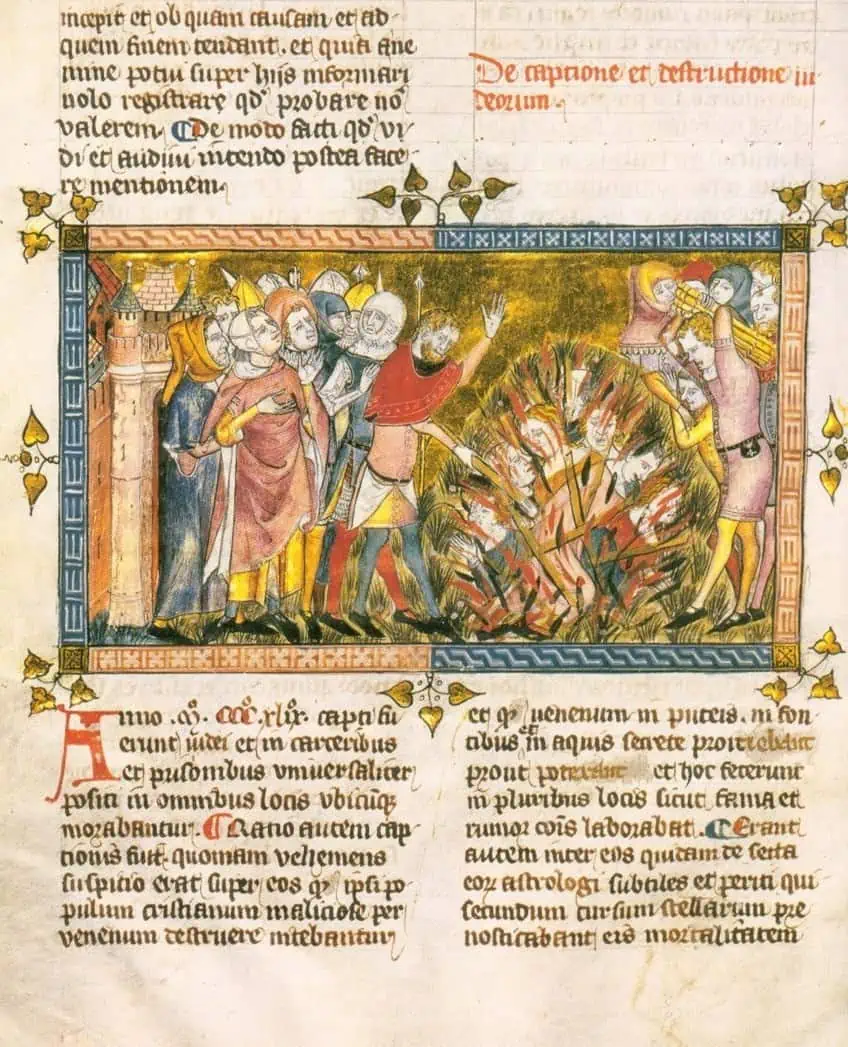

Persecution of the Jews (1350 CE) by Gilles li Muisis

| Artist | Gilles li Muisis (1272-1352 CE) |

| Date | 1350 CE |

| Medium | Illustration in a Manuscript |

| Current Location | The Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium |

This can be seen in works like Persecution of the Jews by Gilles li Muisis. This manuscript illustration depicts a group of Christians, burning a group of Jewish people. One of the figures, dressed in red, is likely meant to represent a priest. This figure has one hand raised in the air, praising God as he murders the Jewish people in front of them, in the hopes that this would satisfy God enough to put an end to the plague.

The burning in this artwork depicts merely one instance of this massacre, with the first taking place in France in 1348, which was followed by several throughout the continent of Europe.

While the Church’s theoPersecution of the Jews (c. 1350) by Gilles li Muisisry was widely believed, there were those who sought a more medical response to the plague. Naturally, medicine during the time of the bubonic plague was nowhere near the advancement it is now, as illustrated in works like A Plague Doctor Lancing a Bubo by Hans Folz.

A Plague Doctor Lancing a Bubo (1482 CE) by Hans Folz

| Artist | Hans Folz (1437 – 1513 CE) |

| Date | 1482 CE |

| Medium | Woodblock print |

| Current Location | Unknown |

This woodblock print, which was made in Germany in the 15th century, shows how plague victims were treated during the Black Death. In order to remove the illness from the patient, doctors would jab the bubonic or “bubo” boil with a pointed stick. With the limited knowledge they had about diseases, bacteria, and the human body, doctors tried everything to cure the sickness, but it didn’t work.

A figure that often appears in artworks and imagery related to the Medieval Bubonic plague is that of the plague doctor. These were physicians that handled cases of bubonic plague during its reign. Cities employed these doctors to treat infected people regardless of financial situation, particularly the underprivileged who could not afford to pay.

Some locals perceived the presence of plague doctors as a bad omen; a warning to evacuate the area, while others had a divided opinion of them. Some plague doctors allegedly billed their clients and their families extra money for specialized care or fake cures. These doctors were frequent volunteers, subpar medical professionals, or young doctors just beginning their careers; they were rarely seasoned doctors or surgeons. In one instance, a plague doctor worked as a fruit salesperson before becoming a doctor. Plague doctors tended to record death tolls and the number of sick persons for demographic considerations rather than treating patients.

These doctors often appeared in Black Plague art, such as with Doctor Schnabel von Rom (17th century), also known as Kleudung wider den Tod zu Rom. A doctor is shown in this engraving sporting the typical 17th-century plague mask. For ages, there were intermittent outbreaks of the plague, and people were constantly looking for treatments. In order to treat patients without getting sick, doctors would don masks, as they covered most of their faces, though this was an unsuccessful preventive measure.

It is also evident that the reason these doctors became such a popular image was due to these masks, which resembled the skeleton head of a bird, making them look rather macabre. The mask was taken from Italian theatre rather than being specifically designed for the plague.

During times of crisis and devastation, artists react in various ways. They may go into the world and work as front-line combat artists, for example, or they may withdraw to their studios and pursue their own expressions. Art was unpredictable between the late 14th and the late 16th centuries, being influenced by changes in religious beliefs, military operations, and ethnic and racial movements. Following Constantine’s conversion, practically all of Europe was made Christian, which had a major impact on art and lasted for more than a thousand years. Inscriptions, paintings, and sculptures depicting biblical scenes or saints covered churches and monasteries. Death was frequently shown in these early paintings and sculptures as a transitional state between life on Earth and enlightenment. Death was feared after the Black Death and was occasionally seen as God’s retribution for sin. This can be seen in the artworks of the time, most of which feature religious imagery.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Effect Did the Bubonic Plague Have on Art?

During the time of the Medieval Bubonic Plague, the focus of art expanded from traditional religious themes to incorporate contemporary events (albeit through a religious lens). Many artists visually expressed the devastation of the Black Death in their bubonic plague paintings and engravings, many of which featured religious imagery at the forefront, reflecting the pervasive belief that the plague was sent by God as a punishment for sin.

What Were the Most Popular Themes and Motifs in Black Plague Art?

Religious imagery was very common in Black Plague art, whether it was the plague being represented through demons, or saints and religious icons like the Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ as a symbol of healing and rescue. Other popular themes included death, with many Black Death paintings featuring imagery such as skeletons, or the Dance of the Dead motif.

What Are Some Examples of Black Death Artworks?

Some examples of bubonic plague paintings include Madonna of Humility (1345 – 1350) by Guariento di Arpo, Tournai Citizens Burying the Dead during the Black Death (1347 – 1352 AD) by Pierart dou Tielt, Persecution of the Jews (1350) by Gilles li Muisis, A Plague Doctor Lancing a Bubo (1482) by Hans Folz, Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (1497 – 1499) by Josse Lieferinxe, Ill Morbetto (16th Century) by Marcantonio Raimondi, and The Triumph of Death (1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Black Death Art – Artistic Legacy of the Bubonic Plague.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. January 31, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/black-death-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 31 January). Black Death Art – Artistic Legacy of the Bubonic Plague. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/black-death-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Black Death Art – Artistic Legacy of the Bubonic Plague.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, January 31, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/black-death-art/.