Performance Art – Famous Examples of Performance Art

What is Performance art and is Performance art really art? Unlike many traditional art forms, performance artists produce their art live and they are usually the subject of the artwork, sometimes working in collaboration with other performers. Today, we shall look at the history and various types of performance art, as well as examples of Performance art.

Contents

- 1 What Is Performance Art?

- 2 The History of Performance Art

- 3 Types of Performance Art

- 4 Famous Examples of Performance Art

- 4.1 The Anthropometries of the Blue Period (1960) by Yves Klein

- 4.2 Cut Piece (1964) by Yoko Ono

- 4.3 Shoot (1971) by Chris Burden

- 4.4 Seedbed (1972) by Vito Acconci

- 4.5 Rhythm 10 (1973) by Marina Abramović

- 4.6 Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me (1974) by Joseph Beuys

- 4.7 Interior Scroll (1975) by Carolee Schneemann

- 4.8 Art/Life: One Year Performance (1983 – 1984) by Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano

- 4.9 Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit Buenos Aires (1992) by Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Coco Fusco

- 5 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Performance Art?

Throughout the 20th century, performance artists played an essential role in anarchic art movements including Dadaism and Futurism. When artists grew dissatisfied with traditional art forms such as painting and established types of sculpting, they regularly turned to Performance art to revitalize their creative process. The most notable period of growth of Performance art happened in the 1960s after Abstract Expressionism and Modernism experienced a decline in interest, and it found followers all around the world.

During this period the art form was mostly referred to as “Body art” as it was largely centered around the human form. This symbolizes the era’s “dematerialization of the object” and divergence from traditional forms of media. The art form also reflected the political turbulence of the period, including the emergence of feminism, which stimulated debate about the separation of the political from the individual, and the anti-war movement. While performance artists’ objectives have shifted since the 1960s, the genre has retained a steady presence and has been widely embraced by the traditional institutions and galleries from which it was previously denied participation.

The History of Performance Art

The main goal of Performance art has been to question the constraints of established types of visual art including sculpture and painting. When these forms no longer fulfill the needs of artists – when they became too restrictive, or too far removed from the voice of the ordinary citizens – they have regularly gravitated towards the various types of Performance art to seek out new viewers and explore new concepts.

Performance art adopts methods and concepts from other types of art, as well as from non-artistic actions such as ritualistic or work-like activities.

Performance Art in the Early Avant-Garde Period

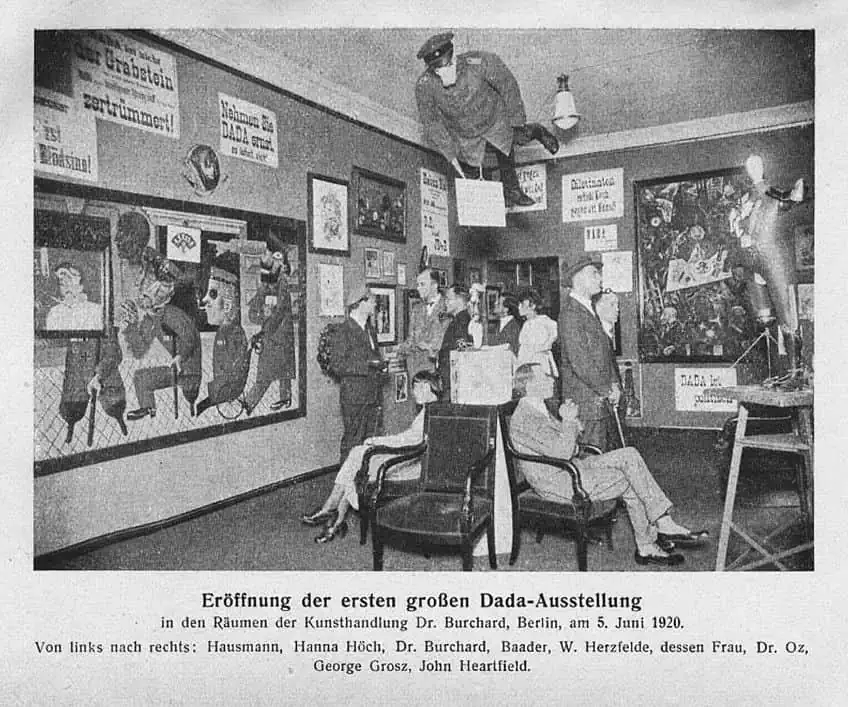

The Performance art of the 20th century can be traced back to the early Avant-Garde movements such as Dadaism, Futurism, and Surrealism. For example, before a single painting had ever been put on exhibit by the Italian Futurists, they would hold performances during the evening where they would read out their artistic and idealistic manifestos. This too was the case with Dadaism, which emerged from a series of gatherings in Zurich at the famous Cabaret Voltaire. These groups regularly staged performances in theater spaces that emulated the styles of political rallies and vaudeville events. Nonetheless, they did so in order to confront current issues in visual art; for example, the Dada group’s often amusing performances helped to convey their disdain for rationality, a trend that had recently arisen from the Cubists.

Performance Art in the Post-War Era

The Post-war Performance art scene can be traced back to multiple locations. The involvement of Merce Cunningham the dancer, and John Cage, the composer, at Black Mountain College in North Carolina contributed significantly to the growth of Performance art at this non-traditional art college. The scene in this era also influenced the output of Robert Rauschenberg, who went on to work with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Cage’s lectures in New York influenced the artistic endeavors of individuals such as Yoko Ono, George Brecht, and Allan Kaprow, who were significant in the Fluxus movement and the emergence of “happenings”, both of which considered Performance art the most significant aspect of their activity.

Performance art in Europe started developing alongside performances in the United States in the late 1950s.

Many European artists, still recovering from the effects of World War II, were disillusioned by the apolitical stance of Abstract Expressionism, the dominant style at that time. They were looking for new art forms that were striking and daring. Fluxus was a key focus for European Performance art, engaging artists like Joseph Beuys. Over the following years, significant Performance art gatherings took place in major European cities including Cologne, Amsterdam, Paris, and Düsseldorf.

Performance Art Styles Around the World

Additional forms included the works of collectives united by similar ideologies, such as the Viennese Actionists, who defined the movement as “not merely a type of art, but most importantly an existential attitude. The Actionists adopted certain elements from American action painting but modified them into an intensely ritualistic theater that attempted to confront apparent historic amnesia and restore stability in a nation that had only recently been a collaborator of Adolf Hitler. These Actionists also opposed government surveillance and limits on mobility and expression, and their dramatic acts culminated in their imprisonment on many occasions.

Art Corporel, or Body art, constituted an avant-garde collection of techniques in France that placed body language at the heart of their artistic output. The Gutai was the first post-war Japanese artistic collective to abandon established art techniques, preferring the immediacy of performance. They created large-scale multimedia settings and theatrical events that emphasized the body-matter connection. Artists like Gustav Metzger established a technique called “Auto-Destructive art” in the United Kingdom, in which things were aggressively broken in public performances that focused on the Cold War and the prospect of nuclear war.

Performance Art and Feminism in the United States

The growth of second-wave feminism paralleled the emergence of Performance art in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. Female artists chose Performance art as a provocative visual medium to express their discontent with social injustice and to take control of the discourse concerning women’s sexuality. This allowed women to convey their anger, passion, and self-expression via Performance art, empowering them to talk and be heard like never before.

Instead of integrating into other previously established, male-dominated styles, female performers decided to take advantage of an ideal opportunity to create their own performance art style.

They typically addressed topics that their male peers had not yet considered, offering new perspectives to the world of art. Hannah Wilke, for instance, questioned Christianity’s historical oppression of females in Super-t-art (1974), in which she portrayed herself as a feminine Christ. Females have made up a considerable proportion of Performance artists both during and following the movement’s inception. At this time, the Vietnam War also generated substantial material for Performance artists. Artists like Joseph Beuys and Chris Burden, who produced in the early 1970s, opposed American imperialism and probed political agendas. Performance art has gained a large following in South America, where it contributed to the Neoconcretist movement.

Later Developments of Performance Art

With the popularity of performance art in the 1970s, it appeared that this fresh and vibrant movement would maintain its appeal. Yet, the 1980s market boom and the resurgence of painting posed a massive challenge. Collectors and galleries increasingly want content that could be physically sold. As a consequence, performance art went out of vogue, yet it did not completely vanish. Likewise, the American artist Laurie Anderson became popular during this time period with dramatic stage acts that used new media and openly highlighted the changing realities of the day.

Female performance artists were especially reluctant to abandon their newfound artistic expressions, and they remained active.

There was enough material in 1980 to present the show A Decade of Women’s Performance Art at New Orleans’ Contemporary Arts Center. The show, coordinated by Moira Roth, Mary Jane Jacob, and Lucy R. Lippard, was a comprehensive survey of artworks done in America throughout the 1970s and featured photographic and textual documentation of events. Throughout the 1980s in Eastern Europe, Performance art was regularly utilized to express societal criticism. As the 1990s progressed, Western nations started embracing multiculturalism, which contributed to propelling Latin American performers to new heights of popularity.

Tania Bruguera and Guillermo Gomez-Pena were two such artists who took advantage of the new opportunities provided by huge biennials with worldwide reach, and they showed work in Mexico and Cuba regarding, poverty, oppression, and immigration. Performance art thrives at times of turmoil in society and politics. Performance art surged in popularity again in the early 1990s, this time propelled by new performers and viewers; themes of racism, immigration, gay identities, and the HIV epidemic were addressed. Nevertheless, this work regularly sparked debate, and it was at the center of the so-called Culture Wars of the 1990s when artists Tim Miller, Karen Finley, Holly Hughes, and John Fleck passed a peer review board to obtain money from the National Endowment for the Arts, only to have it revoked by the NEA because of its subject matter, which dealt with sexuality.

Performance artists nowadays use a broad range of materials and genres, from painting to sculpture and installation. Tris Vonna-Michell, a British artist, combines performance, narrative, and installation. Tino Sehgal combines themes from politics and dances in performances that occasionally take the shape of audience-led dialogues; no typical staged performance occurs, and no recording of the events exists.

Sehgal’s solo exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 2010 demonstrates how close the form has come to being recognized by mainstream art organizations.

Types of Performance Art

Rather than expecting entertainment, audiences for performance artworks generally want to be confronted and challenged. Observers might be pushed to evaluate their own notions of art, and not necessarily in a pleasurable or comfortable manner. Most Performance artists do not fit comfortably into any defined artistic group, and many more oppose having their art labeled as any single sub-style. The movement developed a range of related and overlapping methods, which may be defined as Body art, Actions, Happenings, Endurance art, and ritual. While all of them may be defined and simplified, their defining parameters, like the other elements of the movement, are always changing and some performance artists’ works span several of these types of Performance art. Yves Klein, for example, created certain performances that are connected to the Fluxus movement and have ritualistic aspects as well as elements of the “Happenings”, but his works are also related to Body art.

Action

“Action” refers to one of the first types of modern performance art. It attempts to separate the performance from other types of entertainment in part, but it also reveals how the performers perceived their actions. Some Performance artists viewed their performances as being similar to the type of dramatic connection between artist and artwork that critic Harold Rosenberg discussed in his piece The American Action Painters (1952). Others favored the term “action” because it was open-ended, suggesting that any activity could be considered a performance. Initial conceptual actions by Yoko Ono, for instance, included a number of suggestions that the participant may carry out, such as sketching an imagined map and wandering along a real street based on the layout of the map.

Body Art blurred the line between artist and artwork by putting their bodies right in front as performers, subjects, and canvas, emphasizing the concept of a real first-person perspective.

In the post-1960s environment of shifting social mores and softened views regarding nudity, the body became an ideal vehicle for making politics personal. Feminism artworks flourished in this area as artists like VALIE EXPORT, Carolee Schneemann, and Hannah Wilke used their bodies to bridge the gap between traditional depictions of the experiences of women and newly empowered realities. Several artists, such as Rebecca Horn and Ana Mendieta, addressed the body’s relationship to the outside world, as well as its constraints. Some artists, such as Chris Burden, Marina Abramovi, and Gina Pane, performed appalling violent acts on their own bodies, prompting audiences to rethink their own involvement as observers in all of its shapes and forms.

Happenings

Happenings were a prominent kind of performance that emerged in the 1960s and were conducted in a variety of unexpected settings. They were heavily influenced by Dadaism and demanded more active engagement from viewers, as well as an improvised approach. While certain components of the performance were typically planned in advance, the event’s ephemeral and improvised character sought to provoke the viewer’s critical consciousness and challenge the concept that art must occur as a static object.

Endurance

A multitude of well-known performance artists has included endurance as an element of their work. They sometimes participate in rituals that verge on abuse or physical torture, but the goal is to examine human resilience, perseverance, and tolerance rather than to test the artist’s endurance. Tehching Hsieh, a Taiwanese artist, is one prominent proponent of this technique; Marina Abramovic is another.

Allan Kaprow was likely the most important individual in the happening, while Claes Oldenburg, who would subsequently be affiliated with Pop art, was also actively involved at this time.

Ritual

An element of ritual has regularly played a crucial role in the art of several performance artists. Marina Abramovic, for instance, has utilized ritualistic themes throughout much of her oeuvre, making her performances appear quasi-religious. This illustrates that, although some components of the performance art movement wanted to demystify art by bringing it closer to the spheres of ordinary life, others sought to re-mystify it by restoring to it some feeling of the holy that art had been lost in contemporary times.

Famous Examples of Performance Art

The emphasis on the body in so much of 1960s Performance art has been seen as a result of the rejection of conventional techniques. Others regarded this as a freedom, as part of the period’s media and materials development. Others speculated if it indicated a deeper problem inside the institutions of art itself, an indication that art was running out of resources. Performance art in the 1960s was only one of several different movements that emerged in the aftermath of Minimalism.

When viewed in this light, it is a component of Post-Minimalism, and it may share traits with Process art, another major trend of that umbrella style. Here are several of the most famous examples of Performance art.

The Anthropometries of the Blue Period (1960) by Yves Klein

| Artist Name | Yves Klein (1928 – 1962) |

| Date of Performance | 1960 |

| Medium | Paint applied with bodies on floor |

| Location | Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain in Paris, France |

While painting was central to Yves Klein’s profession, his attitude to it was profoundly unusual, and some critics see him as the quintessential post-war neo-Avant-Garde artist. He first became known for his monochromes, particularly those produced with a strong shade of blue that Klein subsequently patented. He was, nonetheless, interested in performance and conceptual art as well. He covered performers in blue paint and had them smear it around on the floor to create body-shaped formations for this performance.

Klein produced complete artworks from these actions in some instances; in others, he repeated the performance in front of smartly dressed exhibition audiences, usually to the soundtrack of chamber music. “The figures became live brushes at my instruction; the body itself transferred the color to the surface and with absolute precision”, Klein stated, erasing all boundaries between the person and the artwork. It has been speculated that the images were motivated by the markings left on the ground in Nagasaki and Hiroshima after the 1945 atomic bombings.

Cut Piece (1964) by Yoko Ono

| Artist Name | Yoko Ono (1933 – Present) |

| Date of Performance | 1964 |

| Medium | Body Art |

| Location | Performed at Yamaichi Concert Hall, Kyoto, Japan |

This work was originally performed by Yoko Ono in 1964, and served as a direct call to the public to engage in an uncovering of the female form, in the same way that artists have done throughout history. Ono felt that by producing this work as a live experience, she could eliminate the anonymity that is commonly connected with society’s exploitation of women in art. For the piece, the artist sat silently on a stage as onlookers approached her and cut her clothes off with scissors. This compelled people to accept accountability for their voyeurism and consider how even passively watching might hurt the subject being perceived.

It not only acted as a forceful feminist message about the risks of objectification, but it also provided an opportunity for both the performer and crowd to play the roles of artist and object.

Shoot (1971) by Chris Burden

| Artist Name | Chris Burden (1946 – 2015) |

| Date of Performance | 1971 |

| Medium | Photo of performance |

| Location | Performed at F Space, Santa Ana, California, United States |

Burden put himself in danger in several of his early 1970s performance pieces, putting the audience in a tricky situation, trapped between a humanitarian desire to interfere and the stigma against interacting with and touching art installations. Burden positioned himself in front of a wall as one acquaintance shot him in the arm with a rifle and another person photographed the event. It was presented to a select, private audience. One of Burden’s most infamous and violent works, it explores the concept of martyrdom and the artist’s position within society as a type of scapegoat. It might also be about gun regulation and, in the context of the era in which it was created, the Vietnam War.

Seedbed (1972) by Vito Acconci

| Artist Name | Vito Acconci (1940 – 2017) |

| Date of Performance | 1972 |

| Medium | Ramp and microphone |

| Location | Performed at Sonnabend Gallery in New York City, United States |

Vito Acconci lay beneath a custom-built ramp that ran from one wall of the Sonnabend Gallery to the floor. During the event, Acconci lay beneath the ramp masturbating while visitors passed over his concealed location for eight hours a day. Acconci would shout obscenities and utter sexual fantasies targeting gallery visitors through a microphone, which was loudly broadcast through the area for all to hear while performing this illicit activity. Acconci was put in a position that was both private and public in the performance. It also produced a disturbing intimacy between the performer and the audience, leading to various levels of experience and feeling. Subjects were susceptible to discomfort, shock, and maybe even arousal.

Acconci pushed the body art concept of artist and artwork combining as one by situating himself in two positions, both as provider and recipient of pleasure.

Rhythm 10 (1973) by Marina Abramović

| Artist Name | Marina Abramović (1946 – Present) |

| Date of Performance | 1973 |

| Medium | Knives |

| Location | Performed at a festival in Edinburgh, Scotland |

Abramovic stabbed the gaps between her outstretched fingers with a number of 20 knives. Each time she pierced her flesh, she selected another knife from the neatly arranged array in front of her. Halfway through the hour-long performance, she played a recording of the first half-hour and began stabbing the gaps once again in sync with the recording, cutting herself at the same points as she did in the recording. This performance exhibits Abramovic’s utilization of ritual in her works and illustrates what the artist refers to as the synchronicity between past and current mistakes.

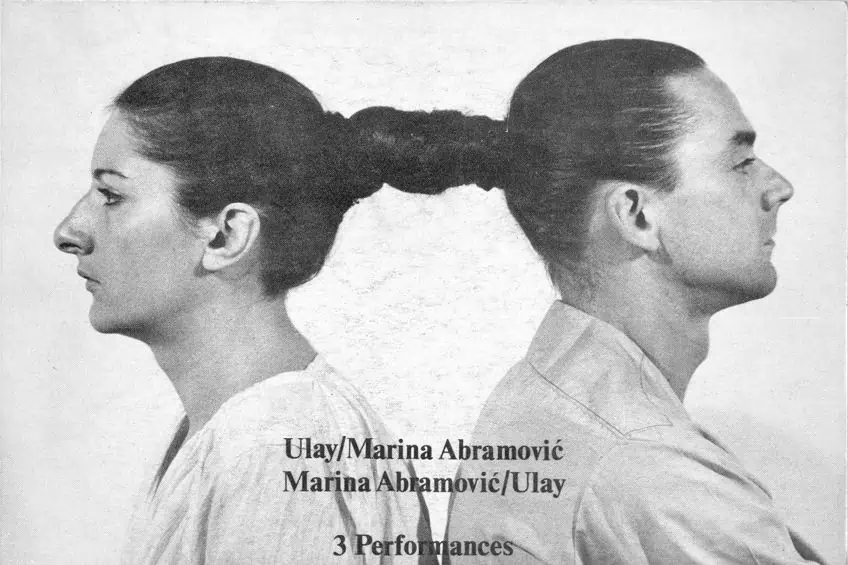

Artist’s book. Marina Abramovic (1978) by Marina Abramovic; Marina Abramović and the CODA Museum, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Artist’s book. Marina Abramovic (1978) by Marina Abramovic; Marina Abramović and the CODA Museum, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me (1974) by Joseph Beuys

| Artist Name | Joseph Beuys (1921 – 1986) |

| Date of Performance | 1974 |

| Medium | Documented photographs |

| Location | Performed at Rene Block Gallery, New York City, United States |

Joseph Beuys locked himself in a gallery space with a wild coyote for three days in May 1974. Previously having said that he would never visit the country while the Vietnam War was happening, this was his first and only performance in the States, and he was transported between the airport and the exhibition space in an ambulance to avoid having his feet physically touch American soil. The performance was inspired by concepts of untamed and domesticated America. Beuys stayed with the coyote for many days, striving to interact with it, in an effort to reconnect with the concept of untamed, pre-colonial America. He planned a series of encounters that would play out throughout the course of the performance, such as wrapping himself in material and employing a walking cane as a “lightning rod”, and stalking the coyote all around the room, stooped at the waist and pointing the cane at it.

Daily deliveries of The Wall Street Journal were used as a toilet by the wild animal, as if to declare, “anything that professes to be a part of America is actually my territory”.

Interior Scroll (1975) by Carolee Schneemann

| Artist Name | Carolee Schneemann (1939 – 2019) |

| Date of Performance | 1975 |

| Medium | Body Art |

| Location | Performed at the Telluride Film Festival, Colorado, United States |

Carolee Schneemann, who works in a number of mediums, rose to prominence in the field of feminist art. One of her most well-known pieces is Interior Scroll. She spread paint on her naked body, ascended a table, and started striking some of the classic postures that models use for artists in life class. Then suddenly, she pulled a lengthy coil of paper from her crotch and began reading the text inscribed on it. It was originally assumed that the text was motivated by her reaction to a male filmmaker’s criticism of her films. Her most renowned films at the time contained images from the Vietnam War and footage of a performance called Meat Joy, which had naked humans crawling around in meat. The filmmaker supposedly remarked on her “personal messiness, the intensity of sentiments, and unsophisticated techniques” – in other words, “feminine” attributes, in his eyes. Schneemann later stated that the text was actually inspired by a letter she wrote to a female art critic who considered her films difficult to watch. Schneemann rejected the sexualization of the genitals by employing her physical body as both a location of performance and a source for the text.

Art/Life: One Year Performance (1983 – 1984) by Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano

| Artist Name | Tehching Hsieh (1950 – Present) and Linda Montano (1942 – Present) |

| Date of Performance | 1983 – 1984 |

| Medium | Rope |

| Location | Performed across New York City, United States |

Hsieh and Montano were tied together by an 8-foot rope for the duration of this year-long endurance performance. They were in the same area but never touched. The rope, in Hsieh’s initial concept, depicted the conflict of humans with one another and their issues with physical as well as social connection. The rope took on new meanings as the performance progressed. It governed, yet broadened, the rhythms of both artists’ lives, creating a visual metaphor of a two-person partnership. The 365-day duration of the project was important in bringing the work from performance to real life. Inside a performance in which living was the artwork, art, and life could not be separated.

Hsieh noted that if the work was only a couple of weeks long, it would have the feel of a show, however, a year provides a “genuine experience of the passage of time and life”.

Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit Buenos Aires (1992) by Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Coco Fusco

| Artist Name | Guillermo Gomez-Pena (1955 – Present) and Coco Fusco (1960 – Present) |

| Date of Performance | 1992 |

| Medium | Costumes and a cage |

| Location | Performed at Columbus Plaza, Madrid, Spain, |

Gomez-Pena and Fusco highlighted the practice of human displays and fetishization of the “foreign” while dressed in absurd costumes, performing stereotyped “native” activities, and being caged. Fusco donned a variety of costumes, including a grass skirt, hair braids, and a leopard skin bra, whereas Guillermo Gomez-Pena chose an Aztec-style breastplate. The pair of performers ate bananas, did “local dances” and other “traditional ceremonies”, and were escorted on leashes to the restroom by museum guards. The performance was executed at Columbus Plaza in Madrid, Spain, as a component of the Edge ’92 Biennial, which commemorated Columbus’ journey to the New World. Despite the fact that it was meant to be a piece of satirical comedy, around half of the audience believed the fake Amerindian individuals were real.

In this article, we explored the various types of Performance art, their history, and examples of Performance art. It has acted as a form of expression, in which artists often employ their own bodies as the instruments or canvases of their works. These works typically conveyed a social or political message and were often turned to after traditional forms of art were no longer capable of expressing the message that the artist wanted to impart to an audience. Much of Performance art is created to provoke a response from the audience, even if it is just an awareness of the voyeuristic nature of their own actions simply through passive (and sometimes active) participation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Performance Art?

Performance art differs from many other more traditional art forms such as sculpting and painting, in that it is often created live in a setting where people are able to observe the process of creation. It is related to body art, as much of it is centered around using the human body as a means of communicating an idea. Very often, the audience is encouraged to interact with the subject.

Is Performance Art Really Art?

Performance art can be regarded as a creative effort that requires thought and skill to execute. The purpose of any artwork is to convey a specific subject matter or feeling, and Performance art definitely meets those criteria. While it may not be a conventional art form, it is a performance in the same way that a ballet or opera is a piece of art. The essence of this type of art is the ability for the performance to act as a canvas on which the artist uses their bodies as the paintbrush, filling the space with color or even just their presence. They often incorporate a ritualistic element, adding to the depth and message of the art piece.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Performance Art – Famous Examples of Performance Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. May 11, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/performance-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 11 May). Performance Art – Famous Examples of Performance Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/performance-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Performance Art – Famous Examples of Performance Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, May 11, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/performance-art/.