Byzantine Art – Explore the World of Byzantine Empire Art

What is Byzantine artwork? For over a thousand years, those within the Byzantine Empire art period created numerous magnificent works to captivate the senses of the audience and transcend them to a higher spiritual realm. From the early Byzantine artwork of antiquity through to the Middle Ages, Byzantine art and architecture have incorporated numerous regional styles. Today we will look at the history and characteristics of Byzantine art, and explore examples of Byzantine paintings and Byzantine sculpture.

Contents

- 1 Exploring Byzantine Empire Art

- 2 The Origins of Byzantine Art and Architecture

- 3 Styles and Concepts of Byzantine Art and Architecture

- 4 Important Examples of Byzantine Artwork, Architecture, and Byzantine Sculptures

- 4.1 Barberini Diptych (c. 527 AD)

- 4.2 Hagia Sophia (537 AD)

- 4.3 Emperor Justinian Mosaic (c. 546 AD)

- 4.4 Christ Pantocrator (c. 6th Century)

- 4.5 Virgin and Child between Saints Theodore and George (c. Early 7th Century)

- 4.6 David Composing the Psalms (c. 900 AD)

- 4.7 Anastasis (c. 1310)

- 4.8 Holy Trinity Icon (c. 1411)

- 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Exploring Byzantine Empire Art

Byzantine art does not always continue in a straight sequence of stylistic advances due to its geographical range and longevity. Because of its Roman Empire roots, Byzantine artwork experienced phases of resurgence that promoted more naturalistic representations that prioritized storytelling, even amid unclassical inclinations that valued structured compositions and symbolic value. Within this timeframe, unique styles of mosaics and icon works of art emerged.

The advancements in frescos, Medieval manuscripts, and figurines would have long-lasting effects not only in Eastern domains like Russia and Turkey but also throughout Europe as well as in contemporaneous religious artwork.

The Origins of Byzantine Art and Architecture

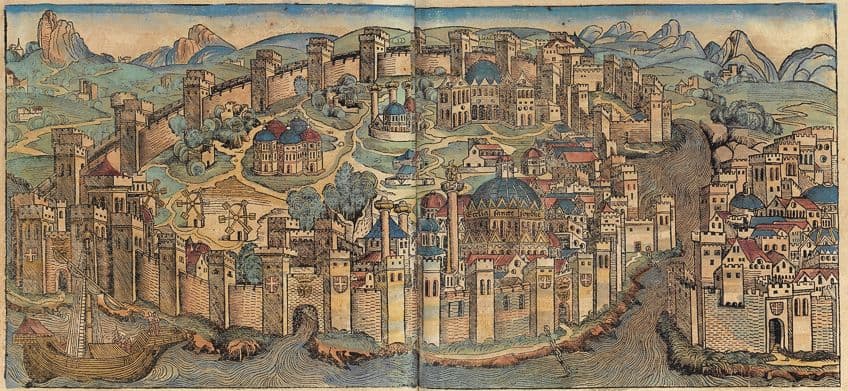

The Roman Emperor Constantine changed the name of the city of Byzantium to Constantinople in 330 AD, establishing the city in modern-day Turkey as the new seat of the Roman empire. In 1453, Constantinople was seized by the Ottoman Empire, which ended the Byzantine Empire. Early Byzantine, Middle Byzantine, and Late Byzantine art and architecture are typically separated by their distinct styles.

The Iconoclastic Controversy, which lasted from 730 until 843, disturbed the Empire’s civic, artistic, and social consistency.

The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the world’s most dominant political, economic, and cultural power in the period preceding the establishment of the Byzantine Empire. Greek mythology greatly influenced Roman religion, as Greek deities were absorbed into the Roman pantheon, with the Romans considering their founding fathers as the origin of their culture and worldwide power.

While the empire assimilated the gods of the communities they conquered in order to maintain civic stability, Christianity’s monotheistic outlook became viewed as a political and societal danger which lead to the Great Prosecution.

In 303 AD, Constantine converted to Christianity, was victorious in the battles for control of the region, and became emperor. Soon after, Christianity was legalized and Constantine founded Constantinople, thereby integrating the regions into the empire and forming a new cultural center focused on Constantinople art.

Early Christian Artworks

Early Christian artwork relied on the techniques and themes of Roman art while recycling them to Christian themes, producing mosaics, frescoes, and panel paintings. Early images of Christ as the traditional Good Shepherd – a youthful man in traditional clothing in a pastoral environment – were made mostly in the Roman Christian catacombs.

Simultaneously, symbols were frequently used to express meaning, and early iconography started to emerge.

Christian churches were erected and adorned with mosaics and frescoes once Christianity became the empire’s official religion. The traditional sculptural style was abandoned because it was thought that sculptures rendered in the round were too similar to pagan icons. There was no significant distinction between Early Christian and early Byzantine artwork.

Before the sixth century, it was impossible to distinguish between Western and Eastern Christian characteristics.

Early Byzantine Artwork

The blooming of Byzantine art and architecture happened during Emperor Justinian’s reign, when he launched an expansive development project in Constantinople and, later, Ravenna, Italy. His most famous construction was the Hagia Sophia, a large temple with a towering dome and light-filled interiors.

The Hagia Sophia’s numerous windows, vivid mosaics, colorful marble, and gold accents provided a template for succeeding Byzantine architecture.

An early Byzantine icon of the saint martyrs Sergius and Bacchus (7th century AD), located in the Khanenko Museum in Kyiv, Ukraine; An anonymous Byzantine master, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In addition to employing 10,000 craftsmen to construct and decorate the Hagia Sophia, the emperor built other studios in Constantinople to teach icon Byzantine painting, metalwork, ivory carving, fresco painting, and mosaics. Constantinople became the empire’s cultural, artistic, and political capital.

The monuments he commissioned are magnificent, lending credence to the notion that his reign was a golden age.

During Justinian’s reign, the Empire stretched extensively throughout many regions, and Byzantine art and architecture inspired modern-day Turkey, areas of Italy, Greece, Spain, the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Eastern Europe. Many of the original Byzantine structures in Constantinople have subsequently been destroyed in the years that followed, and as a result, the best examples of the style can be found in Ravenna in Italy.

Ravenna, Italy

The emperor nominated Maximianus as Archbishop of Ravenna, where he served as the Emperor’s informal governor inside Italy. Maximianus finished building San Vitale in 547 AD, a central-plan temple with a Greek cross within a square that set a precedent for later designs.

The interior of the Church of San Vitale produced an impression of meticulous beauty, with every inch elaborately embellished, having survived practically intact since its dedication.

As realistic images of classical art were discarded in preference for a focus on iconographic formalism, large mosaics representing the emperor helped to establish Byzantine compositional and figurative methods. Tall, slim, unmoving figures with almond-shaped features and big eyes poised frontally on a gold backdrop became the distinctive characteristics of Byzantine art.

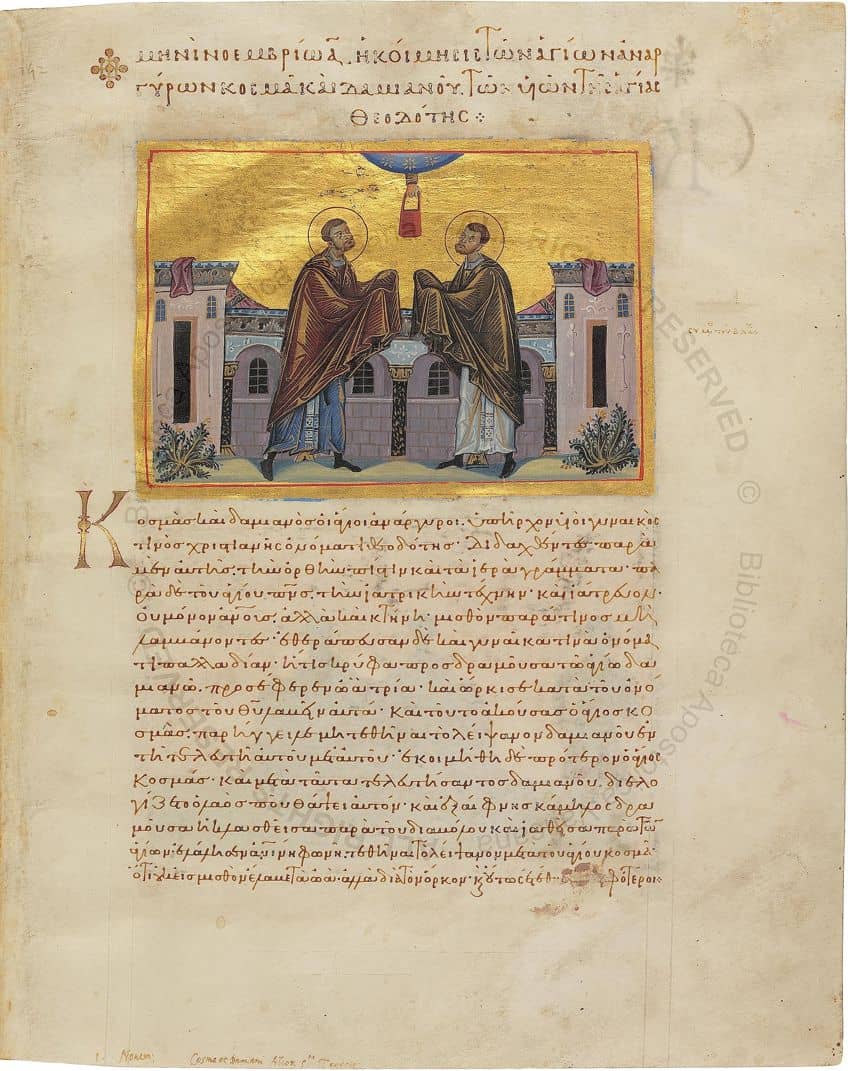

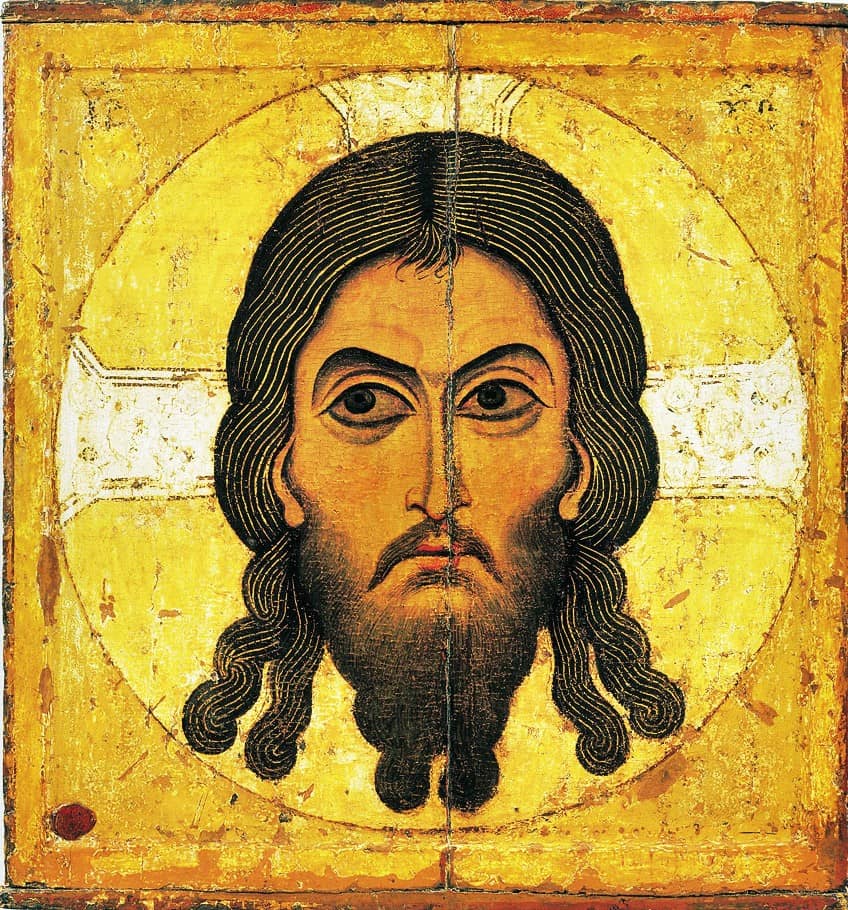

Icons and Acheiropoieta

Small panels representing Christ, icon Byzantine paintings, the Madonna, and other religious figures were popularized by early Byzantine painters. They evolved from ancient Greek and Roman portrait panels, influenced by the Christian traditions of Acheiropoieta, and became symbols of both private and public devotion. An Acheiropoieta was a picture that was said to have been produced miraculously.

According to mythology, St. Luke the Evangelist produced the portrait of the Madonna and Child after they visited him unexpectedly in a vision.

It was possibly the most important worship item in Byzantium, and these miraculous representations contributed to the creation of iconographic forms. Acheiropoieta were frequently attributed to modern miracles. The Image of Edessa was said to have come to the city of Edessa’s aid during its resistance against the Persians in 593 AD.

It was an image of the head of Jesus as he walked to his crucifixion, and for the Christian worshippers, it was not just a symbol of the Almighty but it was as if he were actually there.

Iconoclastic Controversies

By the eighth century, the Empire was under strain and frequently at war, and the debate over the spiritual legitimacy of icons arose in this challenging environment. In 730 AD, Emperor Leo III formally banned religious representations and established a movement known as Iconoclasm, motivated by the assumption that events such as volcano eruptions and war losses were God’s retribution for idolatry.

Long-standing ideological disagreements over Jesus’s human and divine character, as well as a power rivalry between the church and imperial state, fueled the issue.

The Iconoclasts believed that no image could depict both Jesus’s human and divine natures, and that depicting only one element of Jesus constituted heresy. Those in favor of icons maintained that, unlike idols, which represented a false deity, the representations simply portrayed the living Jesus and received their potency from Acheiropoieta.

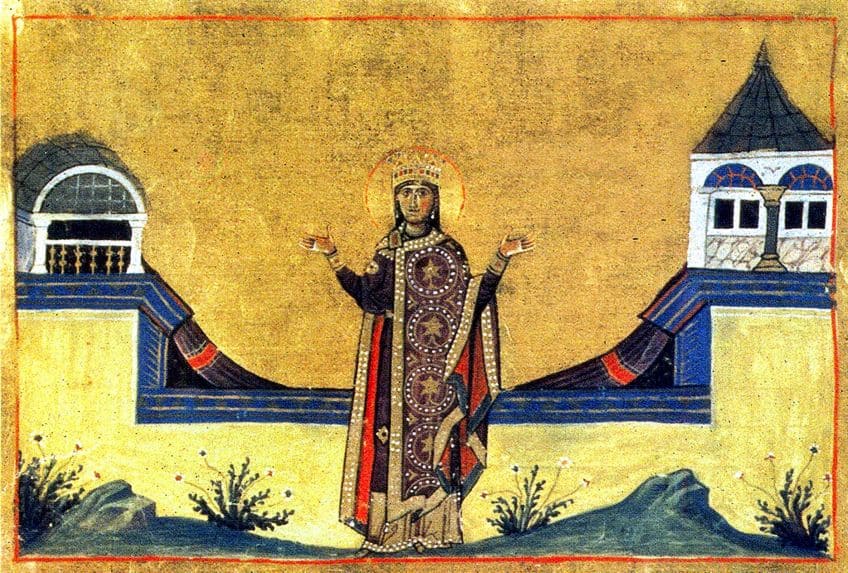

The emperor replaced ecclesiastical authority with imperial order, undermining the church’s power and influence. As a result, the state ruthlessly suppressed monastic priests and demolished icons. The period ended with a shift in imperial authority. In 842 AD, upon the passing of her husband, Emperor Theophilus, Empress Theodora ascended to the throne and convened an assembly that reinstated iconography and removed the iconoclastic clerics.

The event was commemorated at the Feast of Orthodoxy in 843 AD, and icons were joyously returned to the different parishes from where they had been seized.

Nevertheless, the Iconoclastic Controversy had a significant influence on the subsequent advancement of Byzantine art, since the assemblies that reinstated icon worship also established a regulated system of iconographic forms and symbols that were used in frescoes and mosaics.

Middle Byzantine Artwork

The Middle Byzantine period is known as the Macedonian Renaissance because the Macedonian ruler Basil I restored universities and cultivated art and literature revitalizing appreciation for classical Greek aesthetics and knowledge. Greek then became the primary language, and libraries and academics amassed enormous collections of ancient writings. Photios was not only the preeminent theologian of his era but also the finest intellectual.

His Bibliotheca was a notable collection of about 300 texts by ancient writers, and he was a forerunner in recognizing Byzantine civilization as rooted in Greek culture.

As a consequence, there was an almost nostalgic passion for ancient painting traditions that used a more realistic depiction of both people and landscapes. Byzantine art and culture were considered the absolute peak of artistic perfection across Europe, and as a consequence, many monarchs, including those who were politically opposed to the Empire, used Byzantine artists.

Period of Latin Occupation

During the Fourth Crusade in 1204, Constantinople, known for its richness and cultural treasures, was mercilessly ravaged and the Empire was conquered by the Crusade Legion and Venetian forces. The barbarity against a Christian city and its occupants was unparalleled, and historians regard it as a pivotal point in medieval history, causing a permanent deep divide between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, seriously reducing the power of the Byzantine Empire, and directly contributing to its inevitable collapse when it successfully invaded by the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

Numerous significant artworks and religious artifacts were plundered, demolished, or lost.

Some pieces, like the Hippodrome’s bronze works, were transported to Venice and are still on exhibit, while others, including religious artifacts and shrines as well as classic bronze sculptures, were smelted, and the Library of Constantinople was demolished.

Despite the fact that the Latins were forced out by 1261, Byzantium never regained its previous grandeur or dominance.

Late Byzantium

The Late Byzantine period started to repair and rebuild Orthodox churches after the Latin Conquest. Nevertheless, because the Conquest had devastated the economy and left most of the city in ruin, artists began to use more affordable materials, and small mosaic icons became fashionable.

The hardships of the people during the Conquest led to a focus on depictions of compassion in icon painting, such as the suffering of Christ.

Regional variants in icon painting evolved in Bulgaria, Russia, Romania, and Greece. The Novgorod School of Icon Painting, founded by renowned artists Andrei Rublev and Theophanes the Greek, established Russia as a major center. Byzantine art impacted Western contemporary art, notably the International Gothic Style and the Sienese School.

Later Developments

During its almost 1,000-year period, the Byzantine era impacted Islamic architecture, Norman architecture, Carolingian Renaissance art and architecture, and Gothic architecture. The Byzantine Empire ended when the Turkish Ottoman Empire seized Constantinople in 1453 and renamed it Istanbul. Nevertheless, the Byzantine style was retained in Eastern Europe, Greece, and Russia, where a “Russo-Byzantine” architectural style evolved.

Russia experienced a Byzantine Revival in the mid-1800s, which was proclaimed as the national design for churches by Alexander II, who ruled from 1885 to 1891.

The style was employed until World War I, and several architects relocated to the Balkans, where structures in the Byzantine Revival style were built until after World War II. Icon adoration and painting are still important aspects of the Orthodox religion, since Orthodox families have a place devoted to icons, and cathedrals known for their images attract worshipers from far and wide.

Byzantine icons have persisted to have an impact, being used for more conventional religious imagery, such as Luigi Crosio’s late-19th-century representation of the Lady of Refuge, a common iconic image among Catholics. It has also been re-contextualized within contemporary art in creations by Natalia Goncharova as well as other Russian Futurists. Ioan Pope from Romania, Andrew Gould (an American architect), Maxim Sheshukov from Russia, Peter Pearson, Jonathan Pageau (a Canadian sculptor), and Angelika Artemenko from Ukraine are among the contemporary artists working in Byzantine styles and topics.

Zenon Theodor, an Archimandrite, was lauded for his 2008 works of art in Vienna, while Fikos, an artist from Greece, combines Byzantine icons with his love for comic books, street art, and graffiti in what he likes to call “Modern Byzantine Painting.”

Styles and Concepts of Byzantine Art and Architecture

Byzantine architecture, known for its central plan structures with domed roofs, introduced a variety of innovations. Building on to the central dome, Byzantine churches started to surround it with smaller domes. Poikilia, which emerged in Greek aesthetic philosophy to describe how a rich and varied assemblage of components provided a multi-sensory experience, influenced Byzantine architecture.

Byzantine Architecture

Byzantine interiors, as well as the positioning of items and materials inside them, were intended to produce a constantly shifting and lively environment as light exposed the changes in textures and colors. Other methods, such as the use of bands or sections of gold and finely carved stone surfaces, were also used to generate variegated features.

The Hagia Sophia’s capitals, for example, were beautifully carved decorative bands substituted cornices and moldings, smoothing the internal angles and making imagery appear to flow from one area to the next.

In one of his orations, Photios characterized this surface effect as follows: “It’s as if one has entered heaven itself, with no one blocking the path from any side, and has been lighted by the brilliance in changing shapes – gleaming all about like so many stars, leaving one speechless.

Everything appears to be in frenzied motion, and the cathedral itself appears to be circling.”

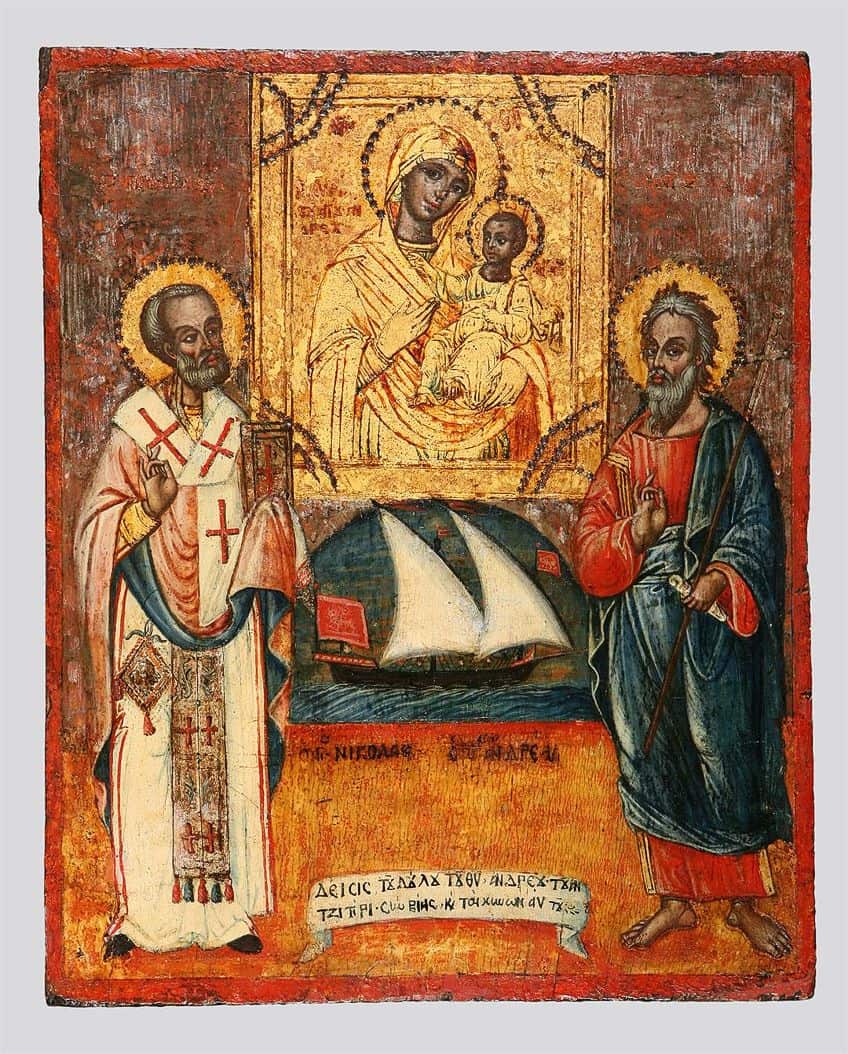

Iconography Types

Byzantine art created iconographic types that were used in mosaics, icons, and frescoes, as well as influencing Western portrayals of religious topics. The early Pantocrator depicted Christ in grandeur, his right hand outstretched in a teaching gesture. The Man of Sorrows, which depicted Jesus’s sufferings, and the Anastasis, which depicted Jesus liberating Adam and Eve from hell, were two more iconographic types.

These kinds gained widespread popularity and were used in Western art, however others, such as the Anastasis, were solely shown in the Byzantine Orthodox tradition.

The iconostasis was the name given to a wall made of icons that divided worshipers from the altar. The Iconostasis developed from the Early Byzantine templon, a screen occasionally adorned with icons, to a timber wall made of panels of icons throughout the Middle Byzantine period.

The wall, which spanned from floor to ceiling and had three doors with hierarchical purposes, designated for church notables, left a gap at the top so that attendees could hear the ritual surrounding the altar.

Novgorod School

Theophanes the Greek created the Novgorod School, which became the major institution of the Late Byzantine period, its impact surviving beyond the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. Because of his painting style and his incorporation of more dramatic scenarios in icons, Theophanes’ artwork was noted for its dynamic vitality. He is considered to have instructed Andrei Rublev, the most famous icon artist of the century, who was known for his capacity to convey profound theological ideas and sentiment in softly colored and emotionally powerful settings.

Dionysius, the preeminent icon artist of the following generation, studied the balance of vertical and horizontal lines to achieve a more dramatic impact.

Ivory Carvings

The sculptural tradition of Greece and Rome was largely deserted during the Byzantine age, as the Byzantine church believed that artwork in the round would bring to mind pagan idols; nevertheless, Byzantine artists invented relief Byzantine sculptures in ivory, which were typically small portable artifacts. Ivory carving was recognized for its exquisite and delicate craftsmanship throughout the Middle Byzantine era.

Byzantine carved ivories were highly prized in the Western world, and as a consequence, the works had an aesthetic influence.

Concepts

Byzantine rulers employed art and architecture to demonstrate their power and status. The emperor was frequently shown in less realistic ways, with compositional cues like size, positioning, and color utilized to emphasize his prominence. Furthermore, the emperor was frequently physically connected with Christ, implying that his rule was divinely destined and so secured.

Byzantine builders and designers made major engineering advancements in creating domes and vaults, starting with the basilica and central designs utilized by the Romans.

Squinches and pendentives were used to provide gentler transitions between the square bases and round domes. Byzantine churches’ architectural surfaces were decorated with frescoes and mosaics, producing sumptuous and spectacular interiors that shone in both lamp and candlelight. The purpose of creating such ornate and supposedly miraculous constructions was to create a feeling of a heavenly world here on earth, a notion that later Gothic architecture completely embraced.

Important Examples of Byzantine Artwork, Architecture, and Byzantine Sculptures

Now that we have discussed the origin and style of Byzantine and Constantinople art, we can take a look at a few examples of Byzantine paintings and Byzantine sculptures. Byzantine paintings were effective tools for spreading and deepening the Christian faith as Christian iconography advanced from the Roman era. During the Byzantine era, several of the now-standard iconographic forms were established and developed. This increasing power of symbols, nonetheless, was not without criticism, igniting fierce and, at times, violent disputes about the role of imagery in the church.

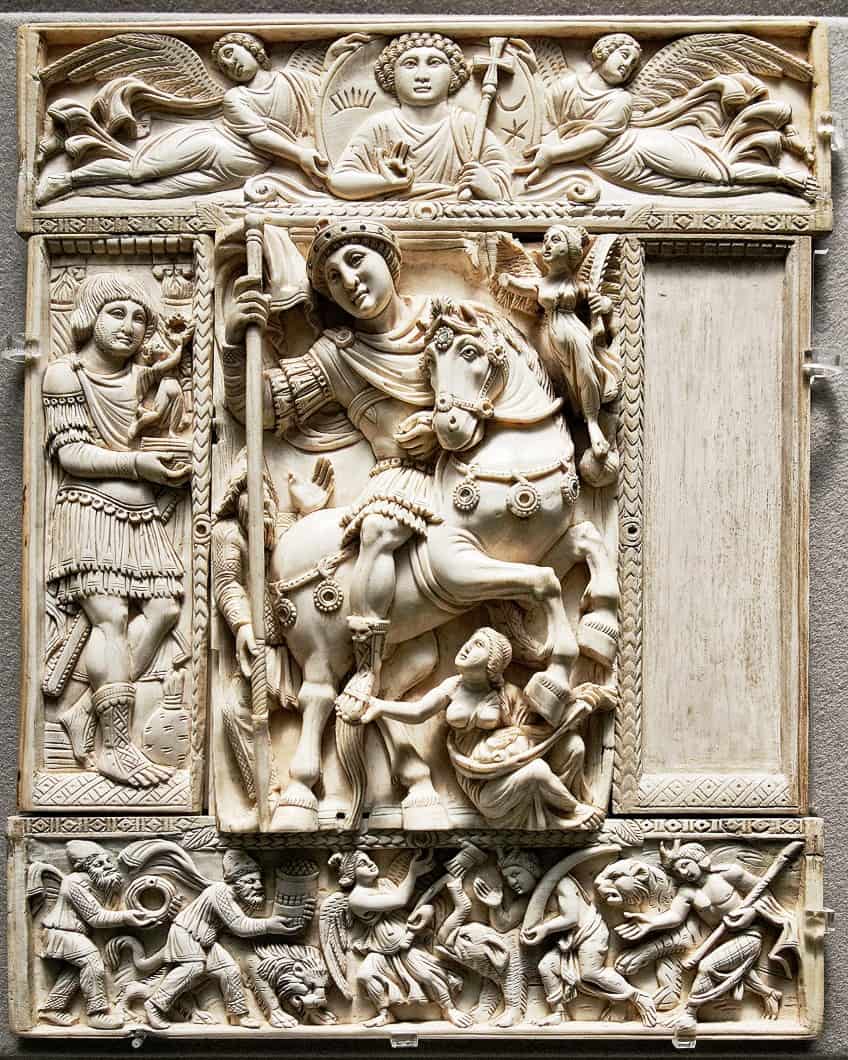

Barberini Diptych (c. 527 AD)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Completed | c. 527 AD |

| Medium | Ivory |

| Current Location | Musée du Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

This ivory relief was formerly part of a diptych, attached to another panel that was later lost. A couple of smaller panels frame the primary portrayal of an emperor on horseback, most likely Justinian. The emperor stares ahead as the strong and powerful horse rears on its hind legs, grasping the pole of a lance in one hand and the animal’s reins in the other.

Three lesser figurines surround him, symbolizing his strength and domination.

Victory, the winged character stands on a globe etched with a cross, carrying a palm branch, another sign of conquest. A wounded barbarian stands to the left of the horse, while the earth is represented by a half-naked woman holding a cornucopia and reaching out with her hand to grab the emperor’s foot. Two angels support a center medallion representing Jesus bearing a cross and surrounded by the moon, sun, and star emblems in the upper panel. A warrior in the panel to the left clutches a Victory figurine while turning toward the emperor.

Every aspect reaffirms imperial power and is represented creatively with dynamic compression; the characters appear to push forward within the frame.

The Early Byzantine era was the origin of ivory reliefs, which had a long-lasting impact on Western art. The piece was produced during the reign of Justinian and exemplifies the Early Byzantine art style, which still relied on classical inspirations, as the emperor and his horse, the angels, and the weapon are sculpted in such high relief that they appear completely three-dimensional.

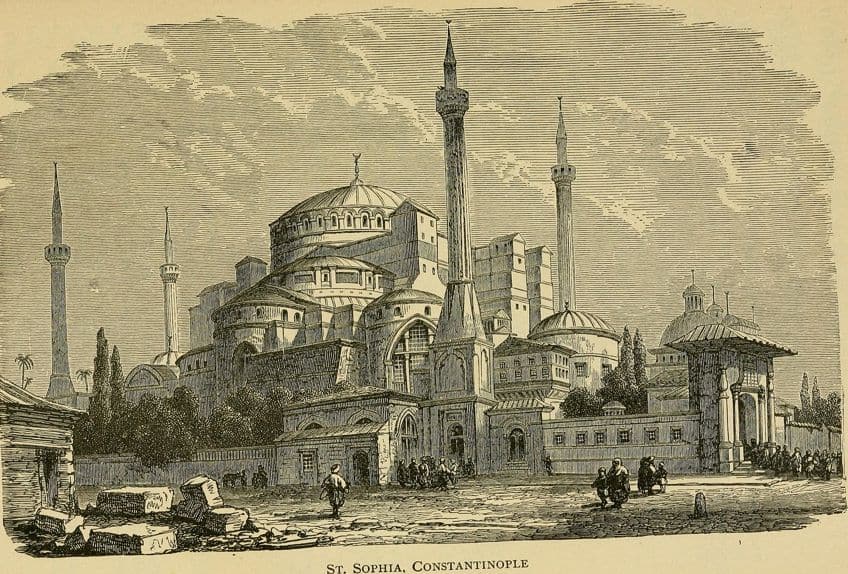

Hagia Sophia (537 AD)

| Artist | Isidorus of Miletus (442 – 537 AD) |

| Date Completed | 537 AD |

| Medium | Brick, mortar, stone, marble |

| Current Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

The Hagia Sophia’s most visible and renowned feature is its huge dome, which soars over the city, while its square brick construction and two towering towers provide the sense of fortress-like sturdiness. The interior is also well-known for its light-filled atmosphere, which produces a wonderful ambiance. The dome is the biggest in the world, thanks to the architects’ innovative use of pendentives, which allow the square base of the dome to bend up into the dome and disperse its weight.

The architects also added 40 windows around the dome to reduce its weight and illuminate its interior. They gilded the frames so that the stone refracted and reflected light, giving the impression that the dome is floating.

When the church was finished, Justinian is said to have cried, “Solomon, I have exceeded thee!” Justinian I commissioned Isidorus of Miletus to restore the church in 532 AD. The old church had been destroyed during riots against Justinian’s rule, and its dedication was intended to commemorate the reinstatement of his centralized power. Simultaneously, the church represented the Orthodox church’s spiritual authority.

The interior construction denoted social hierarchies as well since the bottom floor and top gallery was divided by sexes and classes, with the gallery designated for the emperor and other notable figures. Likewise, the church’s nave entry had nine points of entry, with the Imperial Door, designated for the emperor, in the middle. In essence, the church was a tangible representation of the empire’s religious, governmental, and social order – an earthly yet heavenly metropolis.

Following the Turkish invasion in 1453, the structure was converted into a mosque, and the minarets were constructed. Interior mosaics were painted over with enormous medallions etched with calligraphy.

Nevertheless, the original architecture of the structure was highly regarded, as evidenced by the Ottoman historian Tursun Beg, who stated in the 15th century, “What a dome, competing with the nine spheres of heaven! A superb master has revealed the entirety of architectural knowledge in this creation.” The cathedral served as a model for Ottoman construction, such as the Blue Mosque. The Hagia Sophia is now a national museum, removing it from the theological issues that still surround the place.

Emperor Justinian Mosaic (c. 546 AD)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Completed | c. 546 AD |

| Medium | Mosaic |

| Current Location | San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy |

This renowned mosaic portrays Justinian wearing an imperial purple robe and carrying a big golden dish for the Eucharist’s bread. Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna, whose name is engraved above, appears by the emperor’s side, clutching a gold cross, among three other clerics, one carrying an incense burner and the other a golden Gospel. On Justinian’s right are two men dressed in white garments with a purple stripe, denoting them as officials of the empire, as well as several troops assembled behind a single cross-adorned shield.

The emperor is therefore shown as the pivotal figure between the influence of the church and the strength of the military and government by being placed in the middle.

This mosaic’s unique style characterized Early Byzantine artwork. The naturalistic approaches of classical Greek and Roman artwork were discarded in favor of a hierarchical style that showed characters with direct gazes designed to spiritually connect the audience rather than portraying a realistic depiction of reality. This was one of two murals bordering the altar; the second portrays Empress Theodora, who is similarly escorted, and both images represent the characters as though they are delivering the Eucharistic gifts to the altar, which fills the actual space between the mosaics.

All of the figures are placed frontally in a particular figurative manner, with little feet pointed forwards, tall and thin physiques, oval heads, and large eyes, with no motion implied.

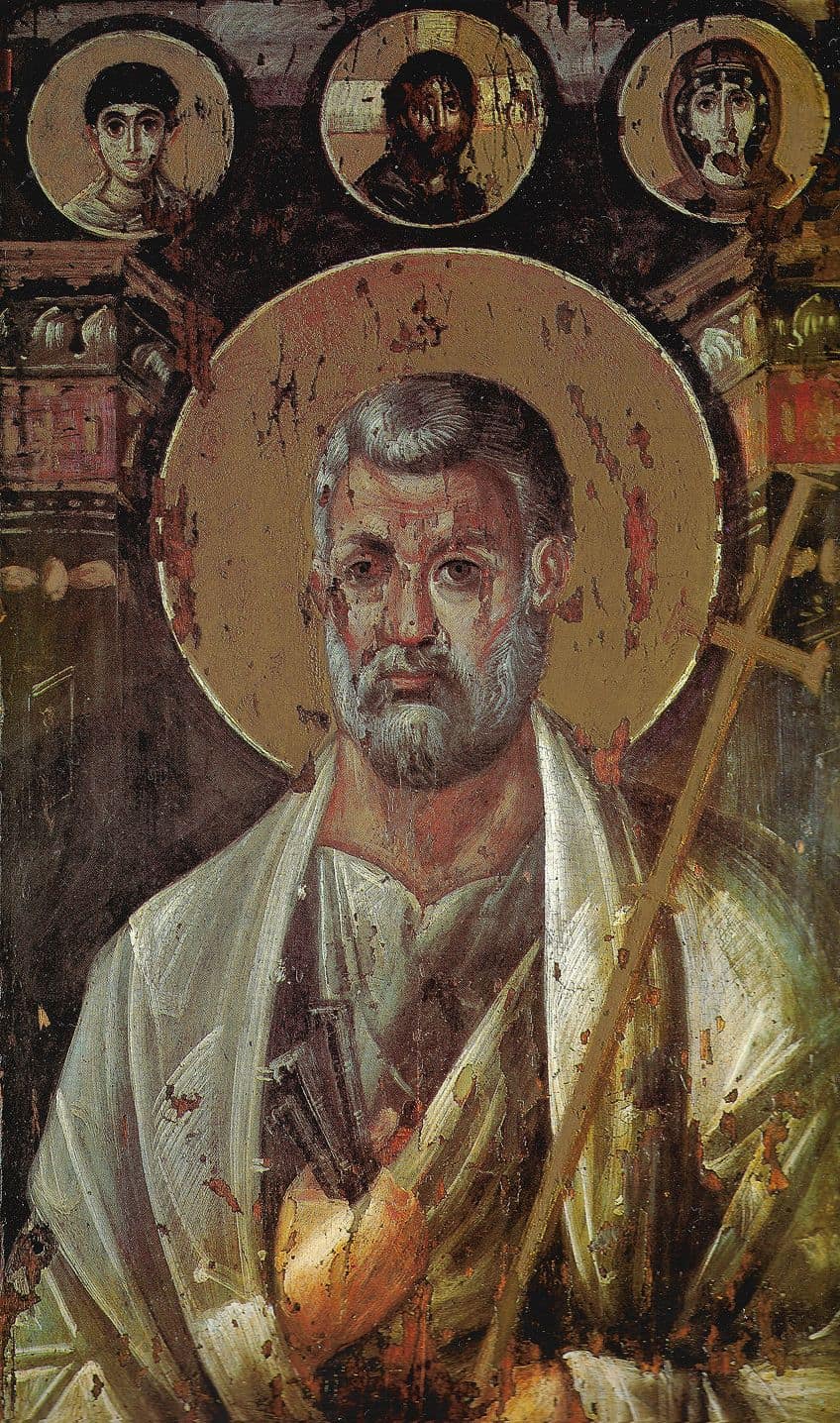

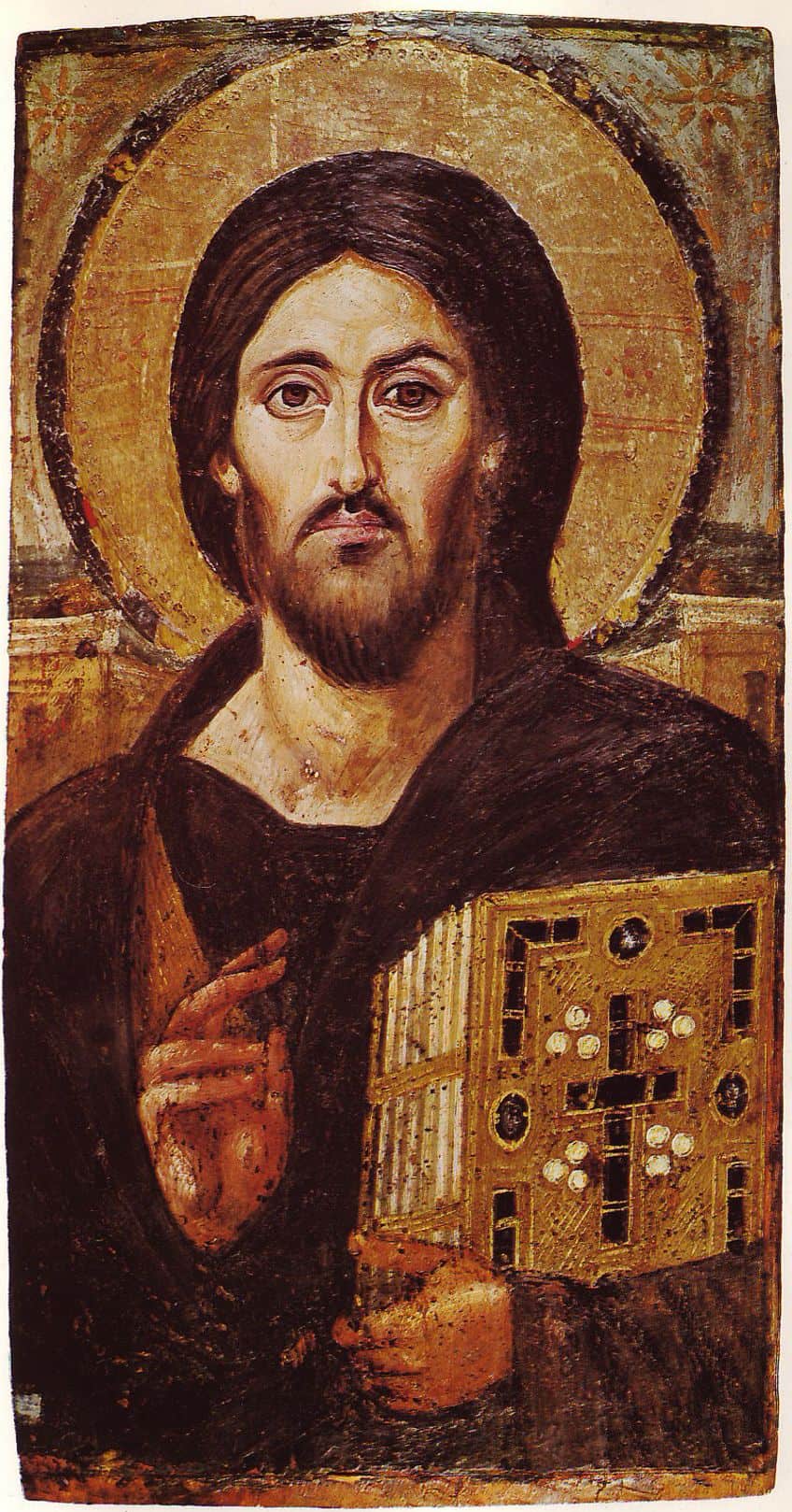

Christ Pantocrator (c. 6th Century)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Completed | c. 6th-century |

| Medium | Encaustic on wood |

| Current Location | Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt |

This encaustic painted hardwood panel represents Jesus in a frontal perspective, his head enclosed by a halo including the outline of the cross. In his left hand, he carries a Gospel book adorned with a jewel-inlay cross and lifts his other hand in a benediction gesture. His purple tunic is modeled with deeper and brighter color tones. His almost life-size body, filling the picture frame, paired with his serene and direct stare, gives the piece an impression of intimacy as if he is being drawn toward the observer.

His radiant face is highlighted by the black lines of his brows, hairline, and eyes, while delicate white highlights juxtapose with darker shadows to invigorate his expression.

The structure and low horizon line behind him provide spatial depth. This is the oldest surviving portrayal of Christ Pantocrator, and it established the standard for the renowned iconographic style that spread across Byzantium and later into Europe. It was produced in Constantinople and delivered as a gift by the emperor to commemorate the establishment of the monastery at Mount Sinai, the sacred place linked with the prophet Moses.

Because of its remoteness from Constantinople, the monastery avoided extensive loss of art during the Iconoclastic Controversy and is therefore known for its extraordinary Early Byzantine artworks.

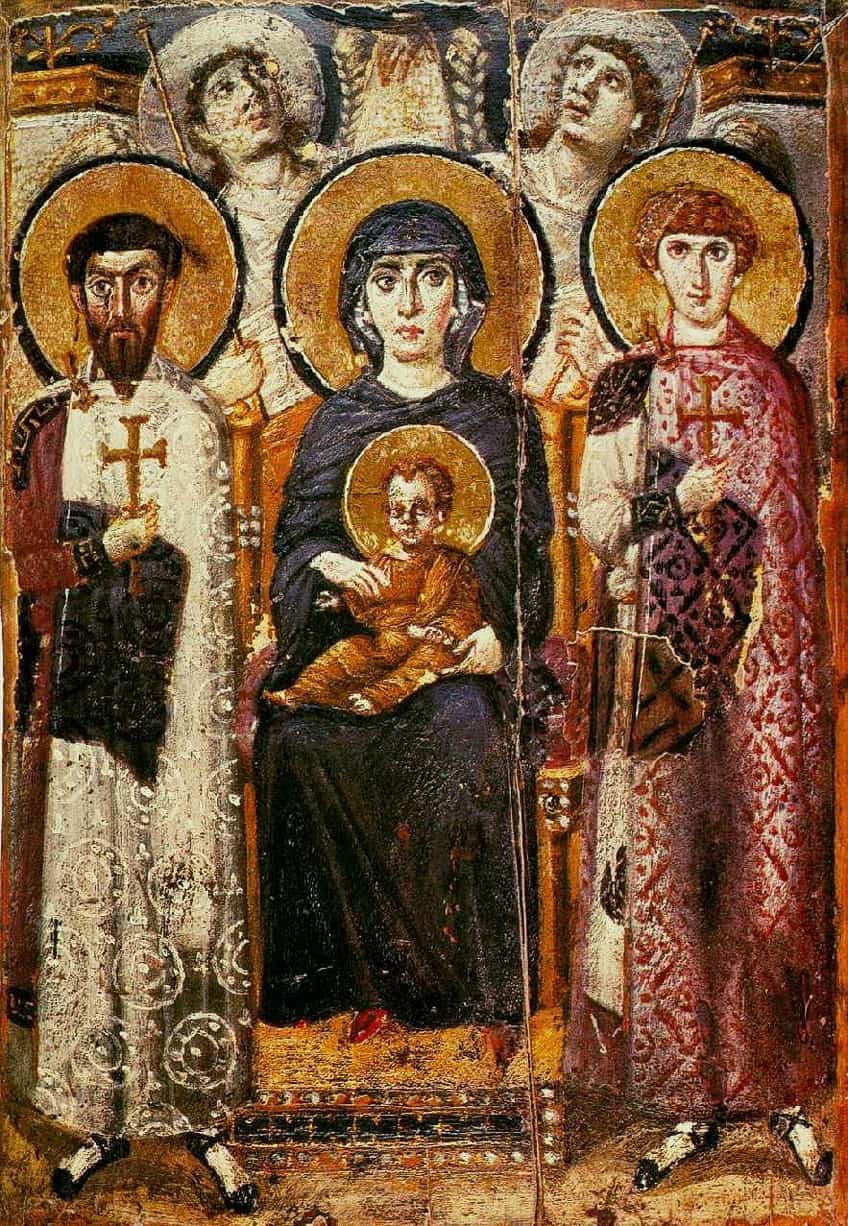

Virgin and Child between Saints Theodore and George (c. Early 7th Century)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Completed | c. early 7th-century |

| Medium | Encaustic on wood |

| Current Location | St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt |

The Virgin is sitting on a gilded throne, cradling the Baby Jesus on her lap, as if introducing him to the observer. Saint Theodore, clutching a gold cross, is positioned to the right of the Virgin, while Saint George, similarly holding a cross, is set to the left of the Virgin. All four individuals are dressed in bright, beautiful robes and are represented facing front, serious and immovable, with large eyes staring at the observer.

The Virgin is somewhat elevated by the hierarchical design, and her chair’s gold edge distinguishes her.

The saint’s knees are bent as if to go forward, evoking antique Roman art and emphasizing the existence of a more material and human world in comparison to the Virgin’s celestial throne. This image is one of the oldest surviving representations of the mother of God, a figure that characterized Byzantine art and impacted Western art, notably the devotion of the Virgin during the Gothic era.

It is also one of the first images of Saint George and Saint Theodore.

Both became venerated saints not just in Byzantium but also in the Western world. Saint George, thought to be a Roman warrior slain for his refusal to renounce his faith, became the fabled dragon slayer of the Middle Ages, and the source for many artworks from the 4th through to the 9th century.

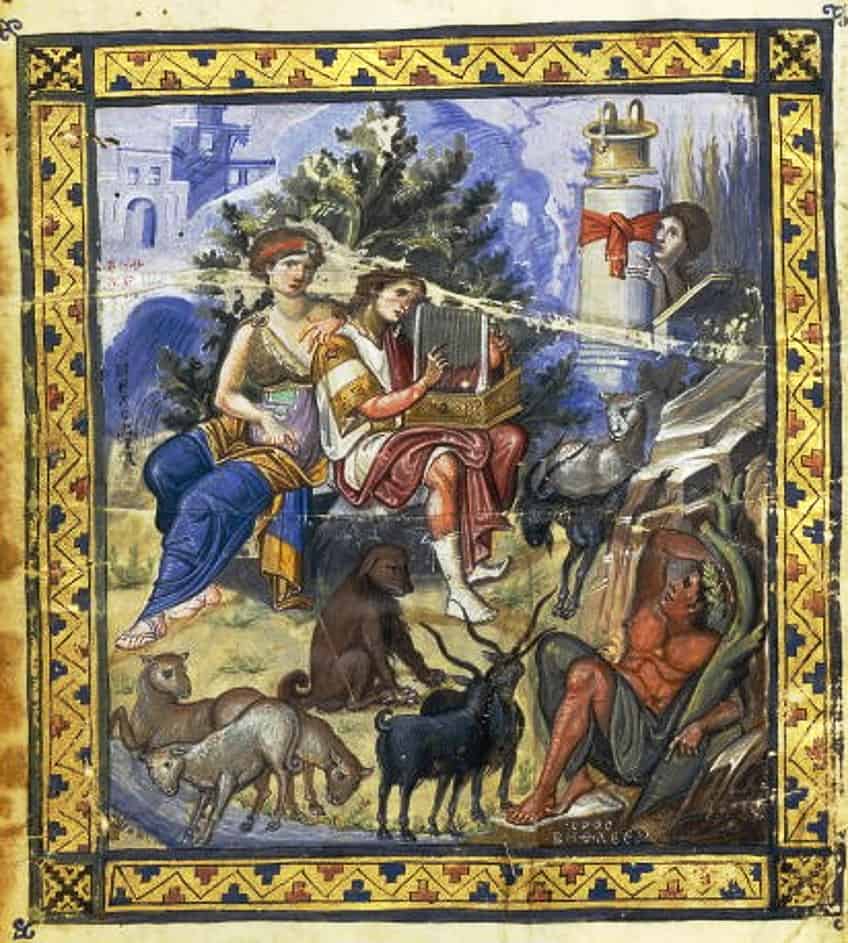

David Composing the Psalms (c. 900 AD)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Completed | c. 900 AD |

| Medium | Illuminated manuscript |

| Current Location | Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, France |

The Biblical King David is sitting on a rock in the middle of this illuminated panel from the Paris Psalter, playing the harp amid a pastoral scene. He is depicted as a young herder, encircled by his flock, which seems to be enchanted by his song. A woman in traditional Greco-Roman attire sits near David, representing Melody, while the other female in the top right portrays Echo, the Greek goddess. A person symbolizing Bethlehem sits on the earth in the lower right.

While it appears to be a biblical scenario, the painting conjures ancient notions of Orpheus, a poet whose voice had the ability to seduce both the natural forces and the Greek deities.

Its overall impression of peaceful pastoral and more lifelike figurative treatment resulted in a dramatic resurgence of classical aesthetics for the period. Psalters were fashionable replicas of the Book of Psalms, several of which were thought to be written by King David. This artwork was notable for its great size, excellent quality, and full-page pictures, implying that it was created for an aristocratic client.

This work epitomized the Macedonian Renaissance with its accurate renderings, images of nature with animals and plants and classical references on 450 pages, and 14 full-page illuminations, featuring eight scenarios from King David’s life.

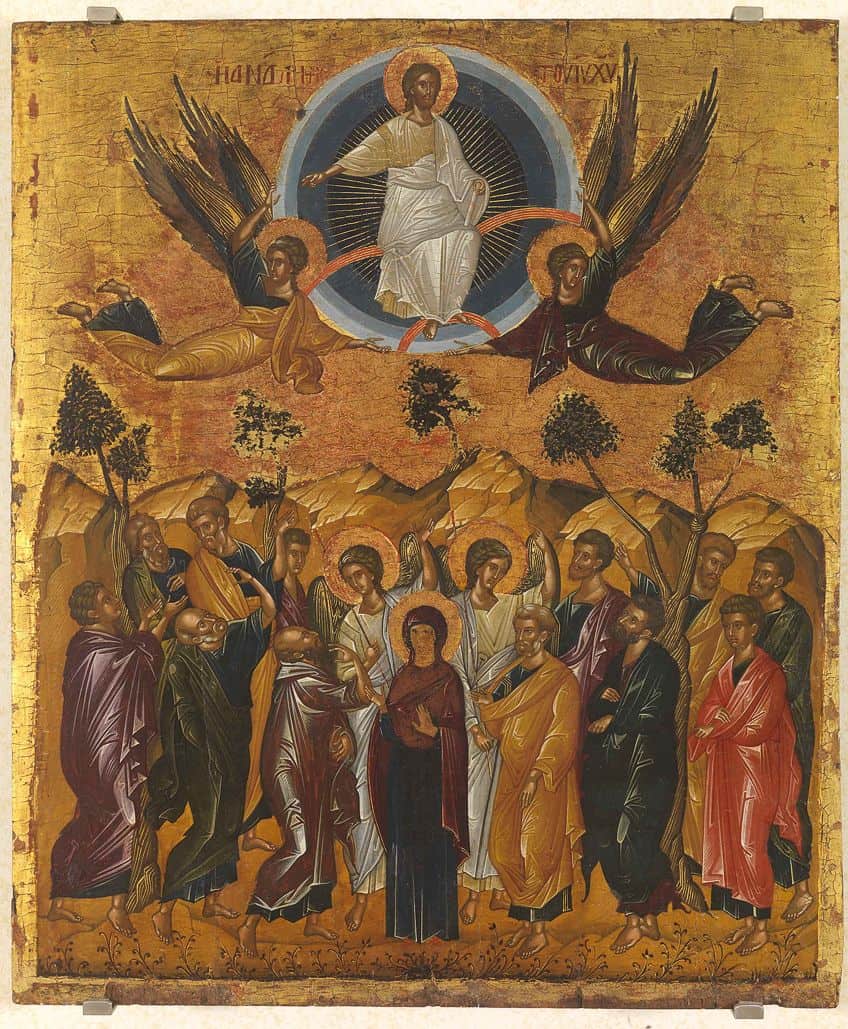

Anastasis (c. 1310)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Completed | c. 1310 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Current Location | Church of the Holy Savior of Chora/Kariye Museum, Istanbul, Turkey |

This painting represents the Anastasis, a popular motif in the Late Byzantine Empire that leaned on the Christian narrative that Jesus saved Adam and Eve from hell between his death and resurrection. Christ, clad in white and encircled by a dazzling mandorla grabs Adam and Eve’s wrists and drags them from their graves on each side of him.

The powerful and dramatic figure was housed in the funeral chapel of Chora’s monastery church, among a sequence of other wall paintings portraying religious themes of Jesus’s salvation of sinful man.

The three major characters move with a dramatic and quick fluidity that is accentuated by the juxtaposition with the immobility of King David and John the Baptist displayed on the left and numerous saints and martyrs portrayed on the right. The black background both below and above, with the Devil and the chains of Hell trodden beneath Jesus’s feet, accentuates his dynamic motion and celestial brilliance even more.

The landscape, with its golden planes and absence of detail, suggests that the figures are in a spiritual world, an unchangeable infinity that only Jesus can transform. The painting is a brilliantly emotive depiction of heavenly triumph.

Such vigor was unprecedented in the previous Byzantine tradition. This style, which was influenced by somewhat earlier innovations in manuscript paintings, was revolutionary. The stylistic shift was the result of humanism’s impact, which began in the Middle Byzantine era. Theodore Metochites, Emperor Andronicus II’s prime minister and a scholar and poet, rebuilt the cathedral and commissioned the artworks to express religious discourse and the burgeoning Byzantine obsession with storytelling.

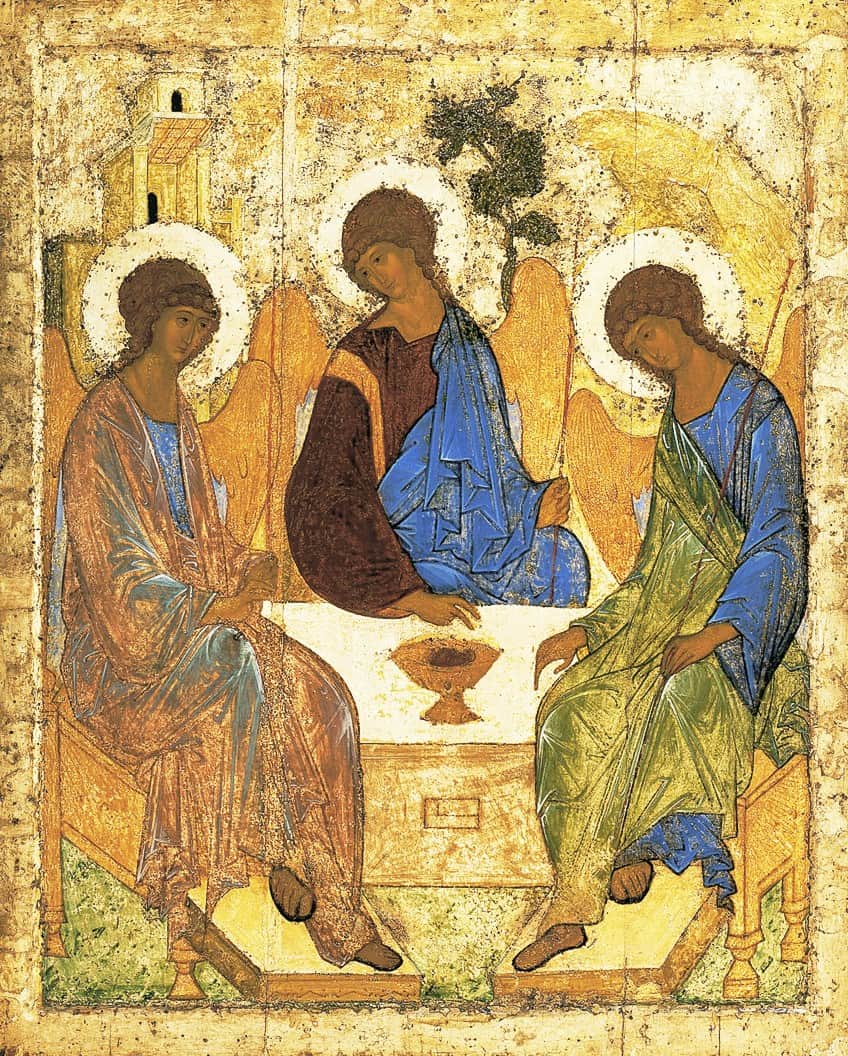

Holy Trinity Icon (c. 1411)

| Artist | Andrei Rublev (1365 – 1430) |

| Date Completed | c. 1411 |

| Medium | Tempera on wood |

| Current Location | Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia |

This, the most well-known of all Russian icons, represents three angels seated around a table with a cup containing the head of a sacrificial calf. The winged figures’ arrangement, beautiful lines, and clothes form a visible circle, indicating their oneness. As they glance toward the angel on the left, the angels in the center and right raise their hands in blessing motions over the cup. Rublev provides a sense of stillness in this circular arrangement.

The piece apparently represents the Biblical tale of three angels visiting the patriarch Abraham, who killed a calf to serve and celebrate his guests, but the icon is a visual statement of the Trinity, the concept that God is one but comprises three people – the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

A solitary tree in the backdrop, above the center angel, relates to the Oak of Mamre, where the encounter occurred, but it also alludes to the Tree of Life and the crucifix upon which Jesus was crucified, thereby linking the center angel to Jesus. The angel’s dark red garment, which represents Christ’s Passion, emphasizes the link even more. The angel on the right is dressed in the greens connected with the banquet of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit descends on Jesus’s disciples, while God the Father is seated on the left, his significance represented by the others’ gazes turning toward him.

All three angels wear blue clothes symbolizing the oneness of the Godhead, and they appear to be involved in the sacred discussion, indicated by glance and gesture, surrounding the chalice that signifies Jesus’s sacrifice. A house in the backdrop alludes to Abraham’s house as well as the abode of eternal redemption, while the mountain refers to Mount Tabor, the Biblical place where the Holy Spirit came.

Rublev took off many of the customary components of the narrative that are generally represented in order to communicate the profound symbolic significance.

Though nothing is known about him, most researchers assume he was a monk at the Holy Trinity Monastery. The monastery was and continues to be regarded as the spiritual core of the Russian Orthodox Church. The Church convened in 1551 to discuss the iconographical canon, and this icon was considered the standard for all Orthodox icons. Rublev’s image stressed spiritual oneness, mutual love, humility, and peace in an era of immense strife and bloodshed. Rublev’s renown has only risen in the modern era.

In the period between Constantine’s Edict in 313 AD establishing Christianity as the official state religion and Rome’s fall in 476 AD, plans were made to split the Roman Empire into two halves, one controlled by Byzantium and the other by Rome. While Western Christianity sank into the cultural chasm of the barbaric Dark Ages, its theological, secular, and aesthetic qualities were preserved by Byzantium, its new Eastern center. Thousands of Greek and Roman artists and craftspeople fled to Byzantium with the transition of Imperial power, creating a new collection of Eastern Christian imagery and iconography known as Byzantine Art. Byzantine artwork has had a long history spanning nearly a thousand years, from early Byzantine art, through Constantinople art, and up to the modern era, Byzantine Empire art has left a lasting legacy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Byzantine Art?

Although not as well-known as the Italian or Northern Renaissances, Byzantine artwork was an important time in Western art history. This style is integrally interwoven with the advent of Christianity in Europe, with numerous paintings still decorating churches around the Mediterranean. It is known for its magnificent mosaics and brilliant use of gold. Byzantine art arose in the ancient Roman kingdom after Emperor Constantine announced the acceptance of Christianity in 313 AD. He relocated the capital from Rome to Byzantium, which was changed to Constantinople in his honor, in 330 AD.

What Is Byzantine Iconography?

With a little explanation, Byzantine religious imagery is pretty simple to understand. After all, both Byzantine and Western European medieval artwork were inspired by the same Biblical stories. The Byzantine Empire was well-known for its religious art, devotional panel paintings, and intricate mosaics. Its capital, Constantinople, was also the center of the Orthodox Christian faith, which is still followed in portions of the Middle East, Europe, and Africa today. Despite differences in creative form, the religious iconography utilized in Byzantine art was relatively stable; it maintained many of the same conventions over the ages.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Byzantine Art – Explore the World of Byzantine Empire Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 3, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/byzantine-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 3 October). Byzantine Art – Explore the World of Byzantine Empire Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/byzantine-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Byzantine Art – Explore the World of Byzantine Empire Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 3, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/byzantine-art/.