Celtic Art – Cultural Artifacts of the Ancient Celts

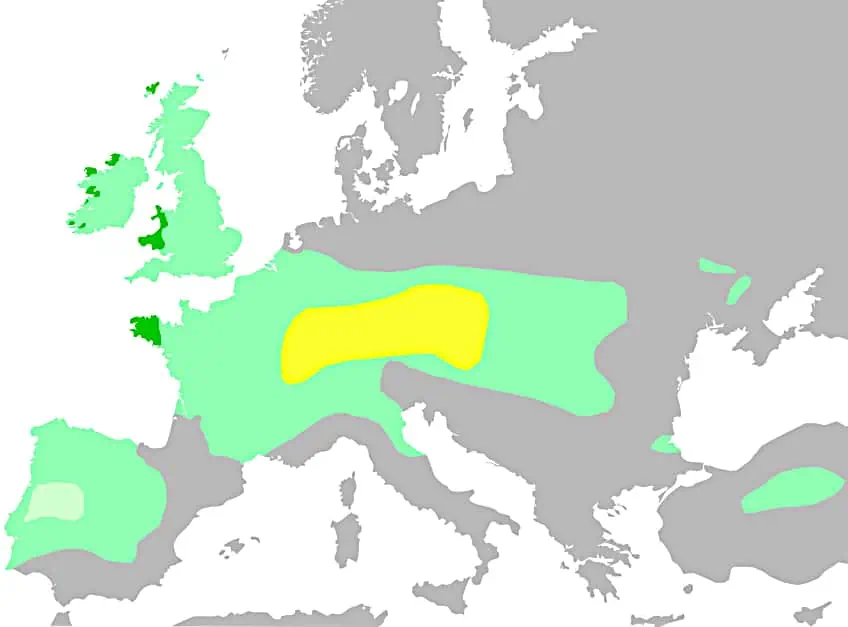

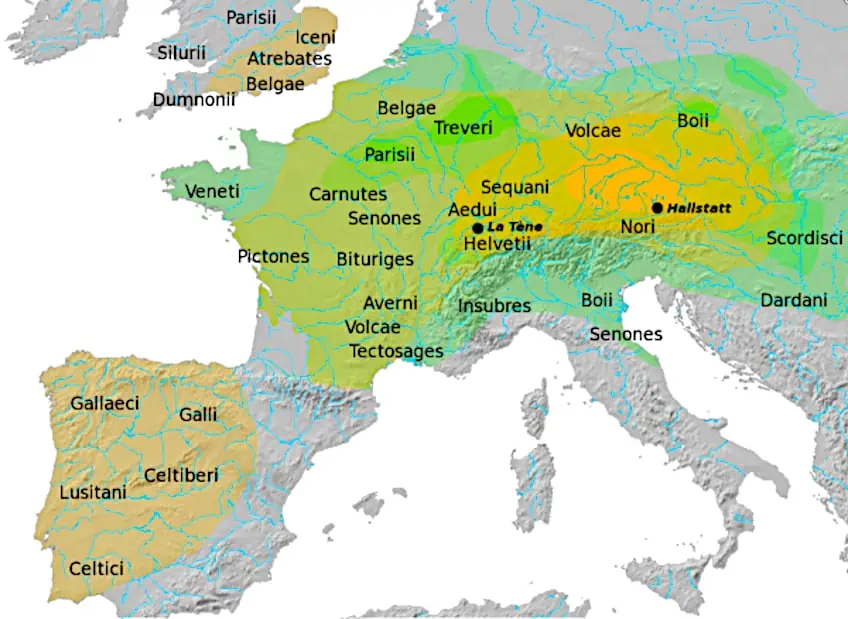

A term spanning such a wide range of history, geography, and cultures as Celtic art is challenging to define. There has been evidence of creative continuity in Europe dating back to the Bronze Age and even the Neolithic period before that, but archaeologists typically use the term “Celtic” to describe the European Iron Age culture from around the 9th Century AD until the Roman Empire conquered the majority of the land. Therefore, Celtic art, sometimes referred to as Gaelic art, is a movement referring to the groups of people in Europe who were known as the Celts. These are people throughout Europe who spoke Celtic languages and dialects. This includes much of Central and Western Europe, specifically in the British Isles. The movement also includes groups of people whose languages are unknown to historians, but share significant cultural and aesthetic similarities with Celtic cultures.

Celtic Art

Celtic art, also known as Ancient Celts Art, Gaelic art and Irish Celtic art, was inspired by Central and Western European cultures, varying from the Thracians to the Romans. The movement has been popular since works from the ancient and medieval periods were recovered in the 19th century CE, and it still fascinates and inspires contemporary artists and craftspeople to this day.

The greatest method to understand the relationships between the prehistoric peoples we refer to as the Celtic people who lived in Iron Age of Europe is through their art, as well as their language.

Ancient Celtic sculptures of mysterious gods and naked warriors, a love of portraying forest animals, the use of intricate and swirling floral designs, and a desire to highlight the elegance of even the smallest and most commonplace of everyday objects are just a few of the features that can be found in Celtic Art.

Generally speaking, the first Celtic migrations from the flatlands of Southern Russia began around 1000 BCE, and by the time they reached Europe during the Iron Age, the Celts had developed their first arts and crafts. Before this time, all European art, craftwork, and architecture were produced by earlier Bronze Age communities, such as the Urnfield culture (1200 – 750 BCE), the Tumulus culture (1600 – 1600 BCE), the Unetice culture (2300 – 1600 BCE), or the Beaker culture (2800 – 1900 BCE).

Celtic Art History and Background

The definition of “Celtic,” as we currently use it, is complex and has evolved much over time. The term Celtic, as well as Gaelic, have become synonymous with Irish and Scottish culture, but this is, in fact, a common misconception, with the culture of the Celts actually gaining prominence in Western and Central Europe.

Background

The ancient peoples who are now referred to as “Celts” spoke a set of tongues that had an Indo-European language ancestry with Common Celtic or Proto-Celtic. Scholars used to generally agree that this same language origin indicated people with a shared genetic origin in southwestern Europe who had expanded their civilization through immigration and conquest. In classical times, the term “Celts” was synonymous with the Gauls.

The English form of these words is more modern, dating back to 1607. The name “Celt” was first used to refer to the people who spoke Brythonic and Goidelic on the continent of Europe, but it was later extended to those in Britain and Ireland thanks to the research of academics like Edward Lhuyd.

During the 18th century, a swell of excitement for the video of Celtic and Druidic cultures was brought on by the interest in “primitivism,” which gave rise to the concept of the “noble savage.” Following the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, an intentional effort was made to display an Irish national identity. This effort, along with its counterpart in other nations, later became known as the “Celtic Revival.” Artists and designers created works that drew on ancient Celtic myths and imagery, resulting in a style that persisted well into the 20th century.

Archaeologists have discovered several cultural characteristics among the Celtic peoples, such as artistic styles, and have linked this culture to the earlier Hallstatt and La Tène cultures. More recent genetic studies have shown that different Celtic groups do not all share a common ancestor and have suggested that the culture may have diffused and spread without necessarily involving significant human migration.

As a result, there is no general consensus amongst historians regarding how much of the so-called ‘Celtic’ culture, language, and genetics were interconnected during the prehistoric era.

History

It is difficult to pinpoint the precise beginnings of Celtic art because archaeologists date Celtic culture’s emergence to 1000 BCE, although art historians typically start with the artwork of the La Tène period in the fifth century BCE. The definition of Celtic art is therefore a broad concept. A significant trend in the history of art, Celtic art is actually defined as three movements attributed to peoples from various eras, places, and cultural backgrounds yet with a common heritage. Celtic art’s underlying theme is symbolism combined with irregular, geometric design.

The sculpture, carving, and metallurgy of the prehistoric Celtic peoples served as the foundation for Celtic art. The development of Christianity in early Britain and Ireland, when local artistic traditions merged with Mediterranean influences introduced by Christian missionaries, is largely responsible for the creation of classical Ancient Celtic art.

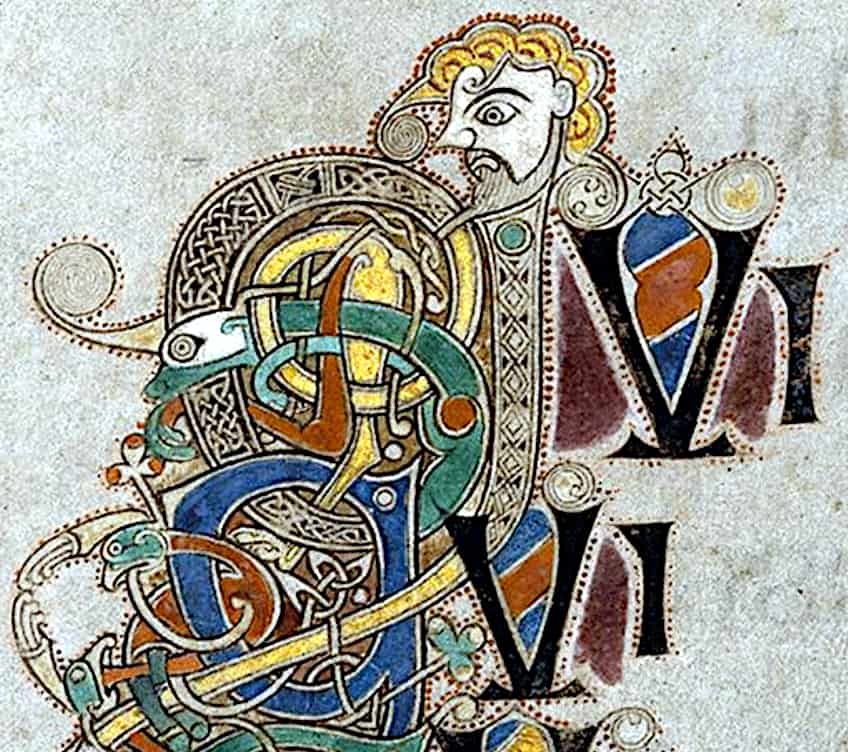

Art historians generally use what is known as the La Tène period as a basis when discussing Celtic art, which roughly spans the 5th to 1st centuries BCE. Another name for this time period, which in Britain goes up to roughly 150 AD, is Early Celtic art. Insular art is the term used in art history to describe the Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, which gave rise to the Book of Kells and other pieces of art, and is what most people in the English-speaking world associate with “Celtic art.

The Celtic paintings and sculptures of the Early Middle Ages, also including the Pictish art of Scotland, is generally the most well-known examples of Celtic art, but does not necessarily represent the movement as a whole. Both the Hallstatt and La Tène Celtic styles incorporated a significant amount of non-Celtic influences, although they both maintained a predilection for geometrical embellishment over figurative subjects, which when they do appear are frequently highly stylized; narrative scenes only arise when there is external influence.

Some characteristics of these styles included energetic spirals, triskeles, and circular formations. Scholars cannot be certain that all typical art from the era is represented in what is still found today because the majority of artifacts that have survived were either forged from metal or carved from stone.

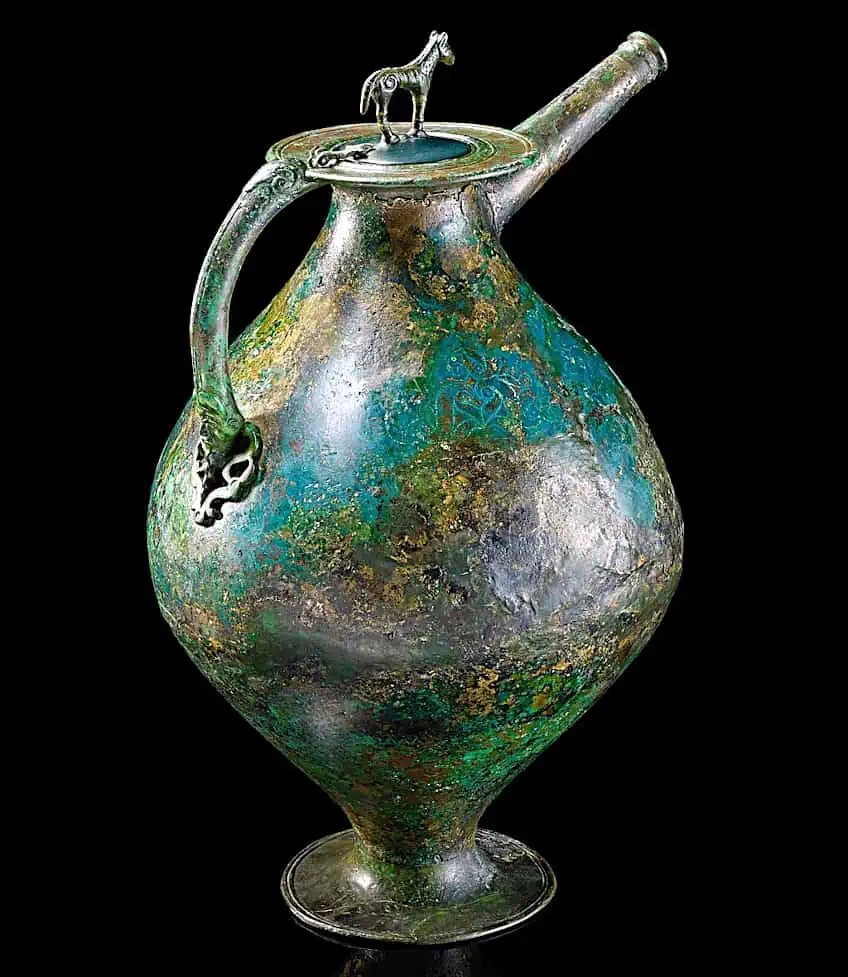

Due to marine trade connections made possible by the Trade route between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean basin, the early Celts carried with them their own cultural styles, which were drawn from the Caucasian Bronze Age, as well as knowledge of the Mediterranean and Etruscan forms. The Celts dutifully assimilated themes from the ancient Danubian heritage after settling in the Upper Danube region. Additionally, they carried with them skills in the creation of iron, metalwork, and jewelry, probably acquired through interaction with the Levant or the Russian Caucasus’ Maikop culture, which produced bronze. (It is thought that the “Gundestrup cauldron,” a later La Tène silver masterwork, was produced in the Black Sea region.)

There were recurring themes in Celtic artwork from Iberia to Bohemia that emerged in a variety of art forms between 700 BCE and 400 AD.

Characteristics of Ancient Celtic Art

Celtic art is typically ornamental, staying away from straight lines and only sometimes employing symmetry. Unlike classical art, there is no imitation of nature and a frequent use of intricate symbolism. The knotwork, spirals, key patterns, calligraphy, flora and fauna, and human figures in Celtic art all display influences from various cultures.

According to archaeologist Catherine Johns, there was an exquisite sense of balance in the arrangement and growth of patterns is a characteristic of Celtic art across a wide range of historical and geographic contexts.

Positive and negative space, filled regions and spaces, and curved forms are arranged so that they form a unified whole. Surface relief and texture were used with control and restraint. The most difficult and oddly shaped surfaces were specifically covered with extremely complicated curvilinear patterns.

Going back to the Celtic revival, following the miraculous discovery of numerous significant objects, including the Hunterston and Tara penannular brooches in 1850, and the growing interest in pre-Roman history, Celtic art saw a remarkable renaissance in the 19th century CE. The art of the ancient Celts inspired painters with its abstract and nonlinear shapes, very frequently spurred by ideals of nationalism and revitalizing cultural heritage, rose once again to prominence and found resonance in such movements as Art Nouveau.

The discovery of the Tara brooches caused the popularity of brooches to rise, and the resurgence quickly spread to America, where Celtic themes were beginning to be seen on gravestones and in buildings.

Celtic Styles of Art

Celtic art was not a completely monolithic form of art. Art historians have noticed several diverging styles within the movement, and have divided it into several periods. These periods include the Hallstatt Period and the La Tene Period, which in itself can be divided into the Early style, the Waldalgesheim style, the Plastic style and the Sword style.

Hallstatt Period

The Hallstatt culture represents the earliest authentic Celtic aesthetic. This originated from the type-site, which existed from around 800 to 475 BCE near the Austrian settlement of Halstaat in the Salzkammergat region. The Hallstatt culture expanded throughout central Europe while being centered in Austria. The Hallstatt culture was established on its successful trade in salt and iron implements across all of Europe, and its affluence was fully represented in the abundance of superbly manufactured artifacts, jewelry, ceramics, tools, and other items found in the graves of its wealthy aristocracy and chieftains.

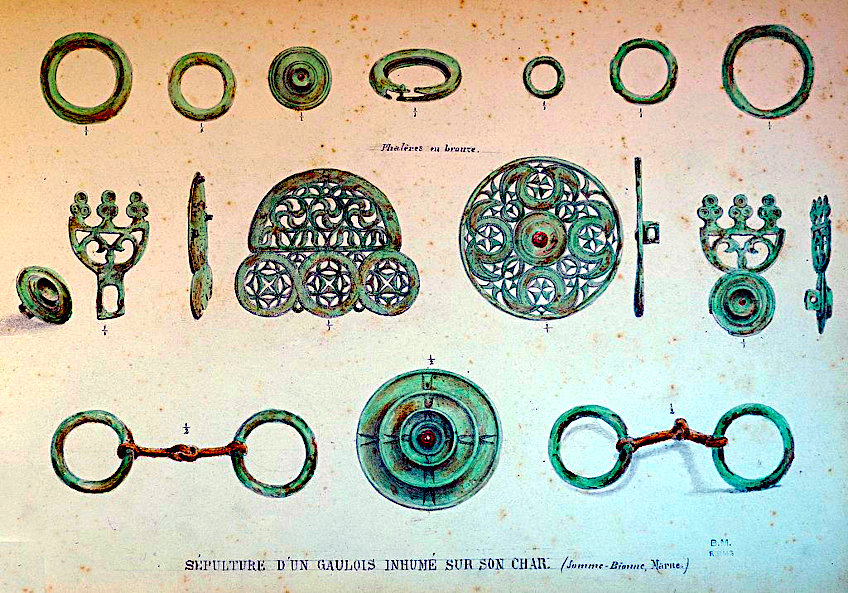

Along with its bronze-based production of ornaments and decorations, Hallstatt art was recognized for its high-quality iron tools and weapons. However, very few gold or silver artifacts from this time period have been discovered. Hallstatt was inspired by the militaristic Mycenaean art and culture, which the Celts had absorbed while traveling across the Black Sea region, between 1650 and 1200 BCE.

Animals, spirals, and geometric patterns were common motifs on armor, accessories, and weapons during the Hallstatt period. They preferred fretwork, knotwork, and birds. They used color, and in pottery that wasn’t painted, they employed a polychrome technique. Weapons and other equipment, such as dual-sided curved axes or curved swords, were fashioned to be both aesthetically pleasing and functional. The Hallstatt art style was often fairly geometric, despite the fact that it evolved and was affected in a variety of ways over the course of its 300-year history. The frequent pairing of figures demonstrated a common concern with rigorous symmetry. Smooth surfaces were frequently broken up by Hallstatt artists, who also used high contrast in color to dramatic effect.

Archaeological digs in Austria during the 19th century found more than 2,000 burials filled with a variety of practical and adorning objects. These findings included a large number of weapons, including axes, daggers, helmets, javelins, spears, swords, and shield plates from the Hallstatt era. Numerous pieces of jewelry made of bronze and iron were also discovered, including brooches, ring embellishments, and different kinds of glass and amber beads, many of which were embellished with geometrical abstractions and animals.

Brooches were particularly prevalent and were found in several types, from animal shaped to those with safety pins, and the Balkan/Greek spiral design.

La Tène Period

The successive Celtic art style is known as “La Tène,” after the type-site that was close to the Swiss settlement of La Tène on the northern coast of Lake Neuchâtel. The site, which was found in 1857, was completely unearthed by Swiss geologists and archaeologists up to 1885. Over 2,500 artifacts in total, most of which were composed of metal, were discovered.

The La Tène period of Celtic art lasted between 500 BCE to 100 BCE, marking the first significant cultural domination of Celtic art. The majority of the objects were weapons, including more than 150 swords (though mostly unused), nearly 300 spearheads, and 22 shield plates. Archaeologists and historians used these findings to assert that the La Tène era was rather militaristic. Nearly 400 brooches were also found among the other items, along with tools and other artifacts. Gold was frequently used by La Tène artists, particularly for jewelry and other forms of decoration.

Gold, bronze, iron, and other types of metal were used to make the majority of the Celtic art from this era that has survived. These metallic items, in addition to the previously described jewelry, also included dishes, bowls, weapons, and sculptures. They were all embellished with scrollwork that was reminiscent of greenery and ivies.

These findings led historians and archeologists to believe that the La Tène style was a more mature take on Celtic art. In his work, Early Celtic Art, (1944) Paul Jacobsthal claimed that the La Tène style could be further divided into four periods; the Early style, running from 480-350 BCE, the Waldalgesheim style from 350-290 BCE, the Plastic style from 290-190 BCE, and the Sword style from 190 BCE onwards. He also asserts that the maturity of this period is likely due to the Celtic people of the Mediterranean’s proximity to the Graeco-Roman culture.

Despite all these findings, very few sculptures were excavated, and no known discovery of paintings from the era. The only notable findings were a few figurative carvings, including horned heads, heads of Janus (the dual-faced Roman god of time and duality) as well as some anthropomorphic figures made from clay, metal, or wood.

Well-Known Celtic Artworks

There are several Celtic artworks and sculptures that have gained notice and appreciation from art historians today. One notable example of these Celtic works is The Battersea Shield. (350 – 50 BCE) This elaborate shield, which was discovered in the River Thames at Battersea Bridge, has become a recognized example of Celtic art. Many academics think that this shield was ritualistic in nature rather than designed for combat due to its thinness, superb condition, and lovely decoration. The reason it was discovered in the Thames has been hotly contested, with some speculating that it was a religious offering—possibly for the river god. This is consistent with the find at La Tène in Switzerland, which also included bones from both animals and people as well as swords, brooches, lance heads, and different chariot parts.

These discoveries suggest that there was another ritualistic activity that involved the offering of weapons as well as the sacrifice of people and animals.

The superior craftsmanship and exquisite design of Celtic weaponry indicate the warrior culture of the time, where ritual and religion were influenced by conflict and warriors were highly valued. Animals are frequently shown in Celtic art, either to symbolize the strength of the natural environment or a related god. While Celtic art does include Celtic paintings, the movement is predominantly known for its sculpture, jewelry, armor and pottery. As a result, there is very little documented about Celtic painters and their works.

Muiredach’s High Cross (900 – 920 BCE)

| Title | Muiredach’s High Cross |

| Date | 900 – 920 BCE |

| Medium | Sandstone |

| Height (m) | 5.8 |

| Current Location | Monasterboice High Crosses, County Louth, Ireland |

One of the most well-known early Celtic sculptures is the spectacular cross found in Monsterboice, Co. Louth. Roger Stalley, an art historian, has hypothesized that the High Crosses at Kells, Durrow, and Clonmacnoise may have all been carved by the same artist. The so-called “High Crosses” were usually commissioned by nearby monasteries, frequently taking the place of earlier-built wooden monuments. Their functions varied depending on where they were: some acted as memorials for events, others were revered items, and yet others were used as landmarks.

The majority of these crosses, which are still discernible throughout Ireland, are from the years 750 to 1150, however, the early 10th century is when the form peaked. They can be divided into two categories: those with relief images of biblical or saintly situations and those with merely abstract Celtic patterns. The former would have also served to clarify and illustrate significant biblical lessons.

Muiredach’s High Cross, made from sandstone, features a carved image of the crucifixion on its west face and a picture of the final judgment with the elect on one arm and the damned on the other on its back. The cross shaft is lavishly decorated with panels of biblical images that have been broken up. Old Testament scenes, such as the story of Adam and Eve, and of Cain and Abel, are painted on the cross’ east side, and New Testament images are painted on the cross’ west side. These panels were once highly beautiful and may have even been painted in vibrant colors, however, these colors have naturally weathered through time.

Crosses like this would have been an effective source of Christian education for a congregation that was primarily illiterate, as was the norm at the time for the general public. The cross was ordered by a man named Muiredach, most likely the abbot Muiredach mac Dohhnaill, who passed away in 923 CE, according to the inscription on the base of the high cross.

The Battersea Shield (350 – 50 BCE)

| Title | The Battersea Shield |

| Date | 350 – 50 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 77.7 x 35.7 |

| Current Location | British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The shield is made up of a number of separate components that are joined by rivets tucked away beneath the decorative accents. Engraving, enamel, and repoussé ornamentation are used to embellish it. The ornamentation has circles and spirals in the traditional Celtic La Tène fashion.

There are 27 tiny round elevated bronze compartments with red cloisonné enamel that create a sort of swastika that is considered to have been symbolic of good fortune and solar energy. The whirling sun was the name commonly used for this symbol.

Archaeologists claim that the bronze layer of the shield is too thin to have provided adequate protection during conflict, and it exhibits no traces of war damage. Therefore, it is assumed that the shield was fashioned either as a decorative piece or status symbol or expressly for a votive offering and was hurled into the river. The shield’s metal plate would have been fastened to a simple wooden or leather shield behind it.

Although most people today, would link the artwork of the ancient Celtic painters and sculptors, with representations of Irish mythology, the Celts actually came from ancient Central Europe, not Ireland. The terms “Celtic sculpture,” “Celtic paintings,” and “Celtic art history” collectively refer to a number of movements that can be traced to numerous individuals who have a shared ancestry but come from different geographical and historical contexts. These include the Hallstatt period, The La Tène period, as well as what was known as the Early Celtic style, running, the Waldalgesheim style, the Plastic style, and the Sword style. Celtic art, also referred to as Ancient Celts Art, Gaelic art and Irish Celtic art, is linked to ancient groups of people, having “Celtic” stylistic similarities but whose original spoken language is unknown, as well as individuals who have spoken Celtic from prehistory to the present.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Celtic Art Known For?

Celtic art is typically ornamental, rejecting straight lines and sometimes employing symmetry. It lacks the imitation of nature that is at the heart of the classical style, and frequently incorporates intricate symbolism.

What Is Celtic Art Made Of?

Bronze, gold, iron, and other metals were used to make the majority of the Celtic art that survived from this era. These metallic items, in addition to jewelry, also comprise pots, bowls, weapons, and sculpture. They are all embellished with scrollwork that is symbolic of greenery and ivies.

What Crafts Did the Celts Make?

Extensive carvings of flora and fauna were done by the Celts. They also crafted stunning jewelry, such as solid gold necklaces, and bracelets. They enjoyed boldness, even in battle, they adorned their chariots with bronze, and their helmets with gold.

What Are the Different Celtic Art Styles?

Rather than just existing as one specific art style, Celtic art was divided by art historians into several styles, including the Hallstatt period, and the La Tène period. The La Tène style could further be divided into the Early style, running from 480 – 350 BCE, the Waldalgesheim style, running from 350 – 290 BCE, the Plastic style, running from 290 – 190 BCE, and the Sword style, running from 190 BCE onwards.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Celtic Art – Cultural Artifacts of the Ancient Celts.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. June 26, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/celtic-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 26 June). Celtic Art – Cultural Artifacts of the Ancient Celts. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/celtic-art/

Davis, Liam. “Celtic Art – Cultural Artifacts of the Ancient Celts.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, June 26, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/celtic-art/.