Chinese Art – An Introduction to Traditional Chinese Art

From ancient Chinese art that dates back to 10,000 BCE to the most modern Chinese artwork, Chinese art culture is said to be the oldest continuous art tradition in the world. A succession of dynasties throughout Chinese art history would all preserve and adapt traditional Chinese art over the centuries. In China, art created by various dynasties can be distinguished by its distinct adaptations and characteristics. To learn more about ancient China artwork, let’s check out the most interesting facts about Chinese art.

Contents

- 1 Traditional Chinese Art History

- 2 Chinese Artforms

- 3 Notable Examples of Traditional Chinese Art

- 3.1 Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers (c. 8th Century) by Zhou Fang

- 3.2 Five Oxen (c. 8th Century) by Han Huang

- 3.3 The Nymph of the Luo River (c. 10th Century) by Gu Kaizhi

- 3.4 Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy (c. 14th Century) by Yan Liben

- 3.5 A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (1113) by Wang Ximeng

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions

Traditional Chinese Art History

The land of ancient China encompassed a large and ever-changing geopolitical environment, and the Chinese art culture it developed over three millennia reflects these changes and adaptations. Even so, despite significant technical advances, shifts in materials and preferences, and the impact of western ideas, there are particular characteristics apparent in traditional Chinese art that allow it to be described in broad terms and identified regardless of where or from what period in Chinese art history it was created.

These essential characteristics include a conviction in art’s ethical and educational capacity, a respect for nature, an admiration for skillful brushwork, an appreciation for clarity, and an appreciation for observing the particular subject matter from different perspectives.

Additionally, a devotion to well-known designs and motifs ranging from dragons to lotus leaves is also essential. Traditional Chinese art would have a huge impact on its East Asian neighbors, and global respect for its achievements, particularly in Chinese sculpting, pottery, painting, and jade craftsmanship, continues to this day.

The Role of Chinese Art Culture

A significant distinction between China and many other traditional civilizations is that the majority of Chinese painters were not specialists, but rather gentlemanly amateurs who were also intellectuals. They were most often literary men who produced poems and were followers of Confucius and his somber ideals. For them and their viewers in China, art was a method of capturing and presenting the philosophical view of life that they revered. As a result, the art they created is typically basic and devoid of embellishment, and may even appear somber to western eyes.

Throughout most of Chinese art history, art was designed to represent the artist’s exceptional character rather than just his practical creative talents.

Many people who created and appreciated Chinese artwork were searching for Confucian values like purity or clarity. Professional artists, of course, were engaged by the Royal house or aristocratic clients to adorn the interiors and walls of their tombs and beautiful buildings. Hundreds of artisans transformed pricey materials into pieces of art for the few individuals who were able to afford them, but these were not considered artists in the contemporary sense.

Painting and calligraphy were the true honorable traditional Chinese art styles. While the art world now may be afflicted with elitism, it’s nothing new, and the Chinese may have been the first to raise the debates about what is and is not regarded as art. Artistic connoisseurship expanded in China, and more and more individuals became buyers of it.

Manuals were created to assist people in understanding Chinese art history, including useful evaluations of earlier artists’ qualities. In certain ways, art became relatively standardized, with principles to be followed.

As part of their instruction, artists were obliged to research the great masters and imitate their works. The very strict standards of art creation and evaluation were primarily a result of the idea that art should serve the audience in some way. The concept that art should and could convey the thoughts of the producers themselves would not arrive until later in history. That is not to imply that there were not eccentric artists who rejected traditions and made artworks in their distinctive style, as there are in any creative form.

In China, there have been instances of artists painting to music without even glancing at the canvas, another artist who only produced when drunk and used his cap rather than a paintbrush, some who painted with their toes or fingers, and even one painter who splattered ink on the silk sheet spread out on his workshop floor and then dragged an apprentice over it.

Chinese Artforms

Several art forms have been part of Chinese tradition for centuries. These include calligraphy, painting, pottery, and sculpting. Let’s explore each of these in-depth before we look at some notable examples of traditional Chinese art.

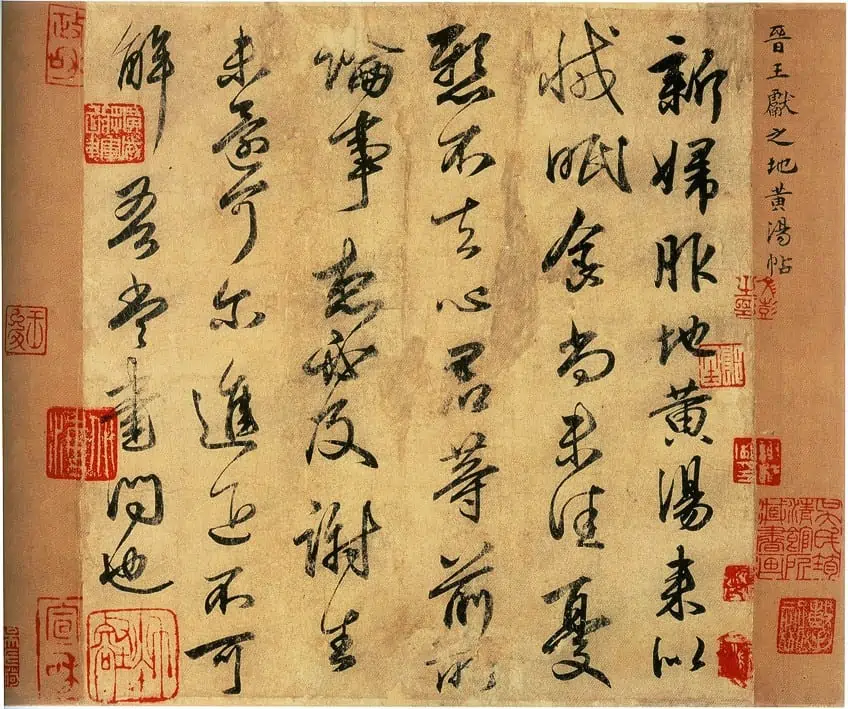

Chinese Calligraphy

The ancient art of calligraphy – and it was surely an art for the ancient Chinese people – sought to exhibit exceptional control and ability by utilizing ink and brush. During the Han era, calligraphy became one of the primary Chinese visual arts, and for the next two millennia, all learned men were required to be adept at it.

Some women, or at least select court elites, did become well-known calligraphers, most famously Lady Wei, who is believed to have trained the renowned master Wang Xizhi.

The art of calligraphy employed various brushstroke thicknesses, delicate angles, and flowing connections to one another – all perfectly positioned to produce an aesthetically attractive whole. Connoisseurship swiftly emerged, and calligraphy, together with ceremony, music, marksmanship, charioteering, and mathematics, became one of the six traditional arts. Writing skills and customs would affect painting, where observers valued the artist’s dynamic use of brushstrokes, fluidity, and variety to create the appearance of depth.

Another impact of calligraphy techniques on painting was the emphasis placed on composition and the utilization of blank spaces. Lastly, calligraphy remained so significant that it featured in artworks to define and clarify what the spectator was seeing, to designate the title, or to identify the location and person for whom it was produced. Eventually, such inscriptions and even poetry became an essential component of the overall design and the artwork itself.

There was also a trend for succeeding owners and buyers to add additional messages, even attaching more pieces of silk to the original work to fit them on.

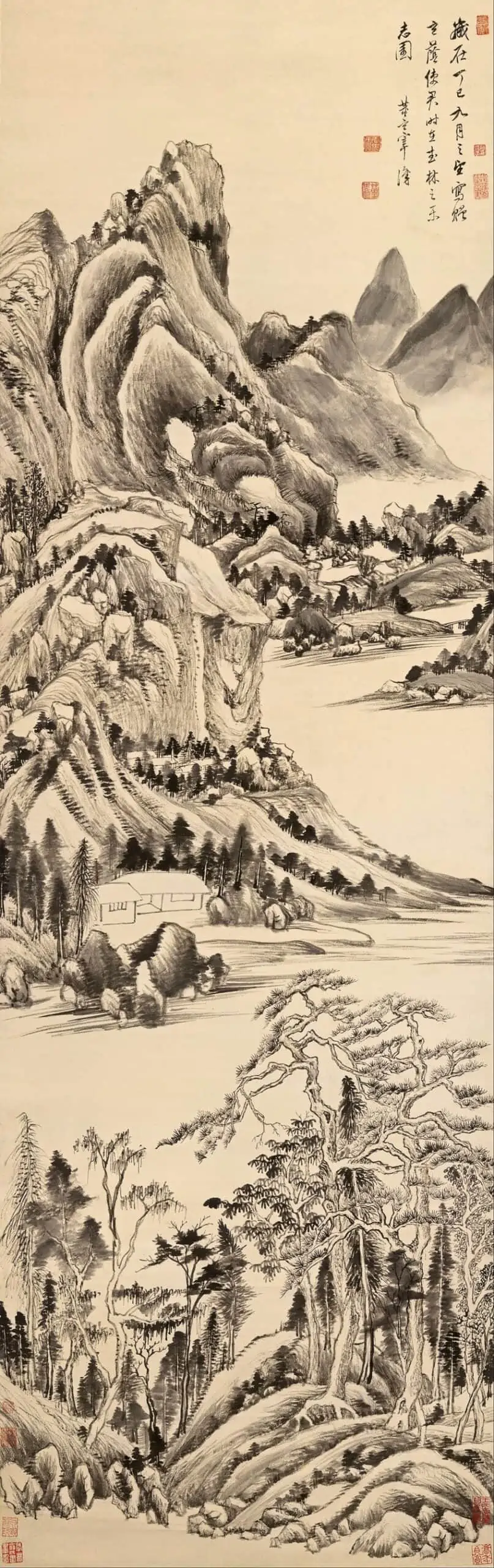

Chinese Painting

Chinese artists painted on a variety of materials in a variety of forms. The most common formats were on walls, screens, boxes, and coffins, silk scrolls made to be held or hung on walls, foldable fans, and book covers. The first painters used wood and bamboo as their primary materials, but plastered walls, paper, and silk were eventually employed. Canvas would not be commonly utilized until the eighth century CE.

Animal hair was trimmed to a tapered end and fastened to a wood or bamboo handle to make paintbrushes. They were, interestingly, the identical tools employed by the calligrapher.

The inks were created by pressing a dry cake of vegetable or animal materials combined with minerals and adhesive on a damp stone. Because there was no commercial manufacture of inks, each artist had to painstakingly produce their own. Landscapes and portraits were the two most prevalent topics in Chinese painting. Portraits in Chinese art originated during the Warring States Period and were typically depicted with considerable discipline, typically because the figure was a renowned scholar, royal official, or monk, and therefore should, by nature, have a strong moral character. that the artist should represent with reverence.

As a result, features usually appear emotionless, with only the tiniest hint of expression or personality subtly communicated. The subject’s personality is often more obviously represented in their stance and relation to other characters in the image; this is especially true with paintings of emperors and Buddhist leaders. There were, however, examples of more realistic portraits, which may be found especially in tomb wall paintings.

Painting historical characters in enlightening moments from their lives that illustrated the rewards of moral behavior was one genre of portraiture.

Naturally, there were other paintings depicting individuals with less ambitious aspirations, such as the famous images of Chinese domestic life set in a garden. Landscape painting has existed for as long as Chinese painters have, but it flourished during the Tang dynasty when painters became significantly more preoccupied with humanity’s role in nature. In Tang artworks, little human figures usually guide the eye through a vast panorama of rivers and mountains. It should not come as a surprise that water and mountains dominated landscape art, given that the Chinese word for landscape directly translated means “water and mountain”.

Rocks and trees are often included, and the entire image is intended to reflect a specific season of the year. Colors were used sparingly, with everything being multiple shades of a particular color or two colors blended, mainly greens and blues. According to the Taoist beliefs in the benefits of studying peaceful nature, agricultural hands are rarely shown in landscapes, and no particular place is meant to be represented. Later eras, on the other hand, would feature more personal and abstract depictions of nature, focusing on specific topics like bamboo gardens.

From the Song dynasty onward, elaborate depictions of a single bird, animal, or flower were very popular, although they were viewed as aesthetically inferior to the other genres of Chinese painting.

However, specific animals became representative of certain concepts and featured in paintings, as they did in other art forms such as bronze sculpture. A deer, for instance, represented money, a couple of mandarin ducks represented a good marriage, and fish represented fertility and wealth. Flowers, plants, and trees all have their significance.

Bamboo grows true and straight like a diligent student should be, cypress and pine symbolize persistence, peaches indicate long life, and each season has its blossoms: lotus, peony, chrysanthemum, and prunus. Depth was produced in paintings by using a lake or mist in the center of the image, creating the appearance that the mountains were further behind.

Other techniques include painting more distant items with softer ink and dimmer strokes, while front objects are made darker and more realistic. Another prominent feature of Chinese art is the use of numerous angles and perspectives to depict a situation.

The 8th century CE silk landscape known as The Emperor Ming Huang Traveling in Shu is one of the most renowned of all Chinese landscape paintings. It is a sweeping and intricate mountain landscape masterpiece in the traditional Tang style, employing mainly greens and blues. The original has been lost, but a subsequent reproduction can be viewed at Taipei’s Palace Museum.

Chinese Sculpting

Large-scale figure sculptures have not lasted well, although some gigantic specimens, such as those carved into the rock face at the Fengxian temple near Luoyang, may still be observed. The statues depict a Buddhist Heavenly King as well as demon guardians. Another well-known example of Chinese sculpting is the life-size Terracotta Army (c. 210 BCE). The mausoleum of the 3rd-century BCE Qin emperor was guarded by almost 7,000 warrior figurines, 600 horses, and many chariots.

Despite being produced from a limited range of integrated body pieces made from molds, much care was put into making each figure distinctive.

Hairstyles and faces, particularly, were altered to create the appearance of an actual army made up of distinct individuals. The Shang Dynasty is well-known for its cast bronze work on a smaller scale. Bronze pots are often three-legged cauldrons, with their legs shaped like birds, animals, or dragons. They can be round or square, and many of them include handles and lids. M asks, repetitive patterns, and scroll motifs are examples of sharp relief ornamentation. Shang painters also created containers shaped like three-dimensional animals including elephants, rams, and mythological beings.

Small-scale sculptures of the Han era took the form of bricks or stone carved and stamped with relief motifs, and it was especially frequent in tombs. Exceptional examples may be seen at Jiaxiang’s Wu Liang Shrine. There are around 70 relief slabs that depict combat scenarios and renowned historical people like Confucius, all of which are described by accompanying writings and span chronological Chinese history in a graphic record comparable to a history book.

Cast bronze figurines of horses were very popular throughout the Han dynasty. These are typically represented in full gallop, with only one hoof standing on the base, giving the impression that they are flying.

From the Han dynasty, earthenware sculptures of solitary standing men, women, and servants are prevalent. Small sculptures and elaborate incense burners were made from cast bronze. These were typically gilded with silver and gold. A gilt-bronze oil lamp in the shape of a servant girl kneeling, dating from the late 2nd century BCE, is a striking example. While huge figure sculptures were sometimes placed outside the tombs of rulers and influential individuals, most of the subsequent sculpture was of Buddhist themes.

By the Tang dynasty, the affluence of Buddhist monasteries had funded a large output of sacred art. The Buddha and bodhisattvas were the most popular topics, as they always were, and they varied from little miniatures to life-size sculptures. People were considerably less static than in earlier periods, with their apparent fluid movement even eliciting criticisms from some that respectable religious characters now seemed more like court dancers occasionally.

Chinese Pottery

The Chinese were ceramics and pottery masters. They made everything from substantial and useful terracotta storage jars to finely designed porcelain bowls, garden benches to vases, cushions to teapots. They created the first glaze goods and the first cobalt blue underglaze ceramics. During the Han period, early advancements in processes and kilns resulted in both greater firing temperatures and the first glazed ceramics.

Pottery, particularly jars painted with a gray slip prevalent in Han tombs, regularly copied the shape and design of bronze vessels, which would be an aim of many potters in the following centuries.

Clay was used to make miniature unglazed replicas of common dwellings that were placed in graves to follow the deceased and, presumably, fulfill their demand for a new residence. Many of these models have a neighboring animal pen as well as figurines representing their residents and animals. Tang potters outperformed all of their predecessors in terms of technical competence.

Greens, blues, yellows, and browns were among the new color glazes created throughout the period, which were made from iron, cobalt, and copper.

Colors were also combined, resulting in the three-colored ceramics that have become synonymous with the Tang dynasty. Rich silver and gold inlays were extensively employed to embellish Tang pottery. Even more renowned ceramics were manufactured throughout the Yuan and Ming dynasties, with their unique and much-imitated blue and white ornamentation, which copied previous Chinese art for design concepts.

Minor Traditional Chinese Arts

Silver, gold, bronze, copper, ivory, enamel, precious stones, colored glass, semi-precious hard stones, wood, silk, and amber were all materials converted into art pieces by creative artisans, but lacquer and Jade were possibly the most typical Chinese materials of the minor arts. Jade was highly valued in China because of its durability, scarcity, purity, and link with immortality.

The hard substance was carved into a variety of ornaments, daily items, and sculptures of humans, animals, and mythological creatures, particularly dragons, using cutting drills and iron implements.

Jade was especially popular for ceremonial artifacts that were mass-produced yet had no utility. The fabrication of “suits” to cover the bodies of the departed in Han imperial tombs was one uncommon yet very exquisite application of jade.

The “suits” are created from up to two thousand intricately carved pieces of jade sewn together with silver or gold wire to match the contours of the body.

Lacquer, a liquid made of resin and shellac, has been used to treat things made of wood and other materials in China since the Neolithic period. It was used to decorate and color furniture, bowls, screens, cups, statues, coffins, and musical instruments, where it could be carved, engraved, and inlaid to represent themes from mythology, nature, and literature.

Notable Examples of Traditional Chinese Art

Now that we have explored the various ancient China artworks, we can have a look at a few examples of Chinese artworks. For the people of China, art represented their daily lives and environments. Many of these examples from Chinese art culture were produced on hand scrolls.

Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers (c. 8th Century) by Zhou Fang

| Artist | Zhou Fang (c. 730 – 800 AD) |

| Date Completed | c. 8th century |

| Medium | Ink and colors on silk |

| Current Location | Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China |

China had a wealthy economy and a vibrant culture under the Tang dynasty. During this period, the subgenre of “beautiful women paintings” was quite popular. Zhou Fang, who came from a wealthy aristocratic family, produced paintings in this genre. His paintings depict the Chinese ideal of feminine beauty as well as the traditions of the period. A voluptuous physique represented the ideal version of Chinese feminine beauty during the Tang dynasty.

Zhou Fang depicted these Chinese court ladies with round cheeks and voluptuous proportions.

The women wear huge, loose-fitting robes with transparent gauze draped over them. Their robes are adorned with geometric or floral designs. The ladies pose as if they are fashion models, but one of them is having fun by teasing a small dog. Their brows resemble butterfly wings. They have tiny lips, large noses, and thin eyes.

Their hairstyles are fashioned in a high bun with various flowers placed inside them such as lotuses or peonies. The women featured always have pale skin due to the application of white pigment.

Even though the artist depicts the women in the paintings as pieces of art, their sensuality is enhanced by this artificiality. The servant girl, holding a long-handled fan, accompanies another royal woman. Even though the servant girl is in the foreground, the lady seems larger due to her greater position. She looks at a red flower in her palm, preparing to decorate her hair with it.

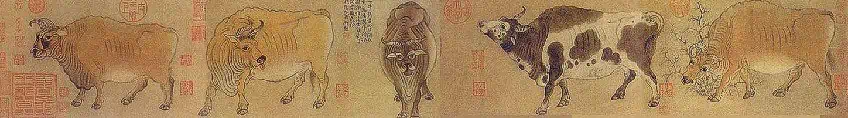

Five Oxen (c. 8th Century) by Han Huang

| Artist | Han Huang (c. 723 – 787 AD) |

| Date Completed | c. 8th century |

| Medium | Ink and colors on paper |

| Current Location | Palace Museum, Beijing, China |

Han Huang, a Tang dynasty governor, painted his Five Oxen in various forms from right to left. They are standing in line. Horns, eyes, and attitudes, for instance, reveal diverse characteristics of the various oxen. It is not known why he chose oxen as a subject though. All through the Tang dynasty, horse artwork was fashionable and encouraged by the imperial palace.

Ox painting, on the other hand, was generally seen as an inappropriate motif for a gentleman’s study.

One of the oxen has a rein, indicating domestication. By incorporating the wild ox in the same scenario, he may have been stating that he would have preferred a tranquil existence on the mountain. However, given his work and status, Han Huang was unlikely to desire to withdraw into seclusion.

It is possible that by portraying the animal with a rein, he was demonstrating his devotion to the emperor.

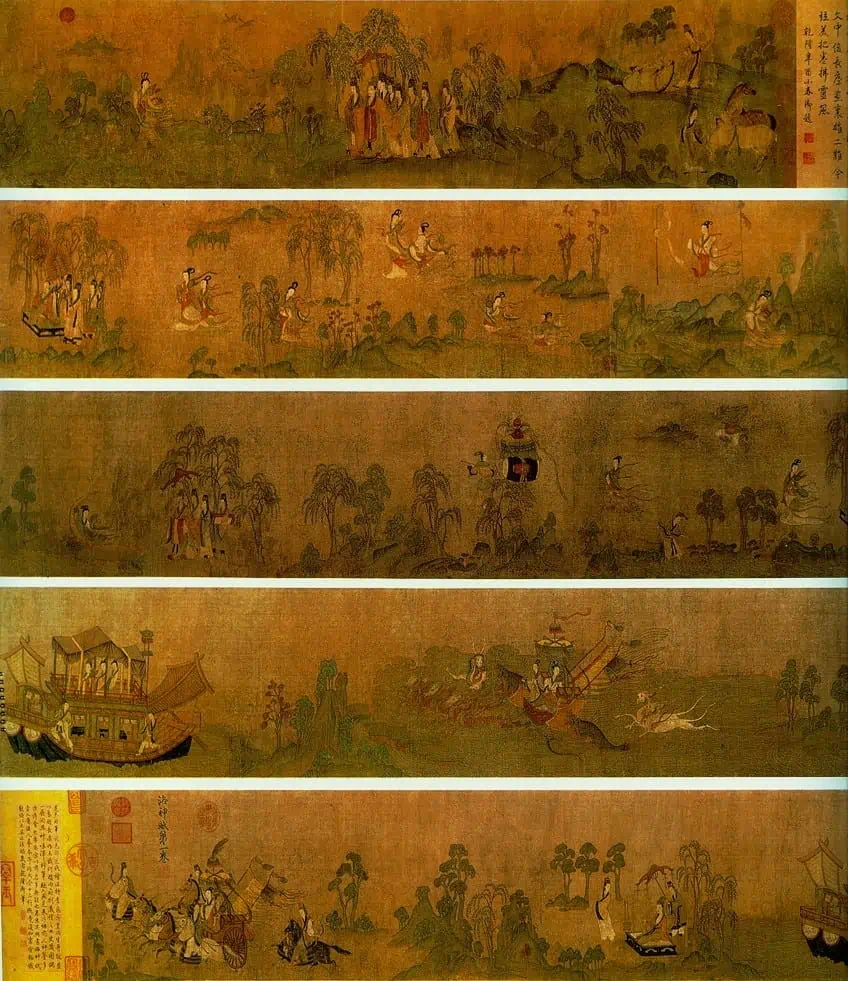

The Nymph of the Luo River (c. 10th Century) by Gu Kaizhi

| Artist | Gu Kaizhi (c. 344 – 406 AD) |

| Date Completed | c. 10th century |

| Medium | Ink and colors on silk |

| Current Location | Palace Museum, Beijing, China |

According to mythology, Cao Zhi, a prince of the Cao Wei kingdom, was infatuated with the magistrate’s daughter. However, when she wedded his brother, Cao Pi, the prince started growing depressed. Afterward, he wrote an impassioned poem about the goddess and earthly love. Gu Kaizhi, a Chinese painter, was inspired by the tale and illustrated the verse in the 4th century.

Sadly, the original artwork has been lost. Artists, however, produced multiple reproductions of it, most likely during the Song dynasty.

The artwork is in the style of a continuous scroll, with segments describing the story. When it comes to trying to understand what is happening in a scroll, then viewing them from right to left is the best method, as this is the sequence in which they were created. Cao Zhi journeys with a group of servants initially and has to cross the Luo River.

He portrays the meeting of Cao Zhi and Fu Fei, the nymph, using a clever arrangement and vibrant colors. Cao Zhi then discovers that she is actually a nymph. Cao is awe-struck by Fu Fei’s charm and falls in love with her. He compliments the nymph’s beauty throughout the verse. Nature is widely represented in many traditional Chinese artworks. Nevertheless, because this handscroll tells the tale, the countryside is only a backdrop for various situations.

Animals and people look larger than simple clouds, trees, and mountains in this scene. Furthermore, the presence of dragons and birds in the artwork creates a magical mood.

Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy (c. 14th Century) by Yan Liben

| Artist | Yan Liben (c. 600 – 673 AD) |

| Date Completed | c. 14th century |

| Medium | Ink and colors on silk |

| Current Location | Palace Museum, Beijing, China |

Tibet adored China’s Tang dynasty in the seventh century. During an official royal visit to China in 634, the Tibetan King was captivated by and sought the hand of Princess Wencheng. He sent envoys and all sorts of presents to China, but they were rejected. And so, the king’s army marched into China, plundering villages along the route until they eventually arrived in Luoyang, whereupon the king’s army conquered the Tibetans. Nonetheless, Emperor Taizong eventually gave the princess to the king. The artist portrayed the encounter with Tibet in this handscroll.

The painting, similar to others from China, is most probably a Song dynasty replica of the original.

The emperor has been portrayed seated in his royal carriage. An officer of the royal court is positioned to his left. The Tibetan emissary seems to be completely awe-struck by the presence of the emperor. The person located on the furthest point to the left is thought to be a royal translator. The Tibetan minister and the emperor are meant to symbolize opposing viewpoints.

Therefore, their contrasting attitudes and physical looks exaggerate the composition’s duality. These contrasts serve to accentuate emperor Taizong’s political supremacy.

Yan Liben depicts the setting in vibrant hues. Additionally, he masterfully defines the characters, giving them genuine expressions. He also makes the Chinese official and the emperor larger than the rest to indicate their rank. This famous handscroll not only has historical value but also demonstrates artistic skill.

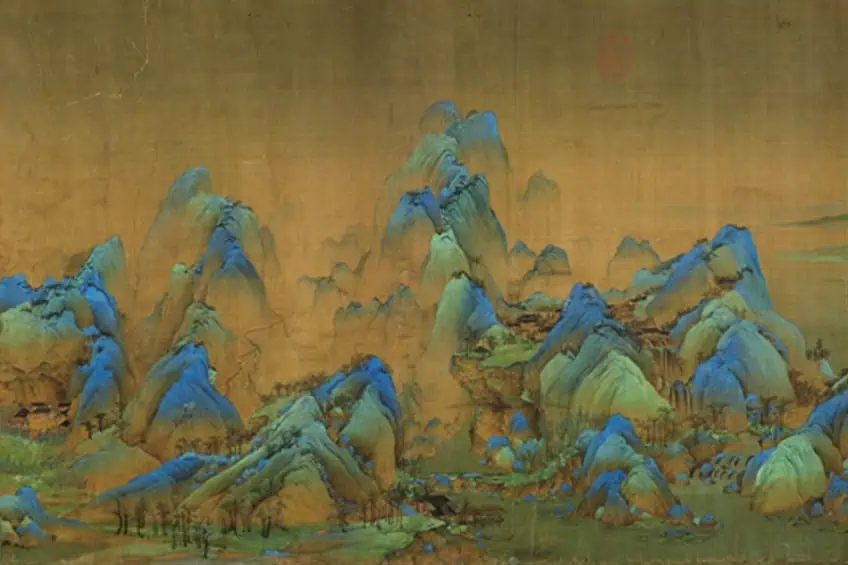

A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (1113) by Wang Ximeng

| Artist | Wang Ximeng (1096 – 1119) |

| Date Completed | 1113 |

| Medium | Ink and colors on silk |

| Current Location | Palace Museum, Beijing, China |

Wang Ximeng was a Chinese artist who liked painting landscapes. He was regarded as a child prodigy, and Emperor Huizong of Song was said to have trained him. Wang Ximeng created this piece while he was just 17 years old.

He died some years later, but he left behind one of China’s largest and most stunning artworks. It’s approximately 12 meters long.

The artwork is a “green-blue landscape” masterwork. The colors malachite green and azurite blue dominate, with traces of light brown. Wang Ximeng presents a panorama from several views. He demonstrates the beauty of the scenery, with its green hills, cottages, temples, and bridges. The artwork is breathtaking in its vibrant colors, vast grandeur, and fine details.

Chinese artists have meticulously portrayed animals, landscapes, and beautiful women for centuries. As we have discovered the facts about Chinese art, we have learned that it has the longest continuous art tradition on earth! Chinese art history is filled with thousands of years of incredible artwork, from ancient China artwork right up to the present day.

Take a look at our Chinese art history webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Depicted in Ancient Chinese Art?

Ancient China artwork is known to have stuck to a relatively limited number of subjects. These include landscape paintings and portraits. Animals were also commonly featured in traditional Chinese art. Another common subject was beautiful Chinese women engaged in everyday activities.

Are the Ancient Chinese Artworks We Have Today the Originals?

Considering that Chinese traditional artists acquired their skills by imitating older masters, distinguishing an original from a replica can be challenging, especially if the piece is quite old. Even if the artist did not intend to create a forgery, the copy may have been mistaken for an original at some stage. As a result, even professionals struggle to ensure authenticity. If you put a handful of experts in a room, you’ll receive several distinct answers regarding an artwork. There are no shortcuts to authentication; it takes a significant amount of time and research, and it remains mostly subjective. Although traditional Chinese artworks are highly valued, the most straightforward option is to purchase a traditional painting with a direct link to the artist who created it. Nonetheless, paintings from the Yuan, Song, and Ming eras are still sought by collectors.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Chinese Art – An Introduction to Traditional Chinese Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 12, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/chinese-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 12 October). Chinese Art – An Introduction to Traditional Chinese Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/chinese-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Chinese Art – An Introduction to Traditional Chinese Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 12, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/chinese-art/.