Egyptian Art – Discover the Influence of Ancient Egyptian Artwork

Ancient Egyptian artwork spans a large period, beginning in Prehistoric Egypt and continuing until the Roman period when the region became largely Christianized. In ancient Egypt, art included many forms, such as Egyptian paintings, Egyptian sculptures, and Egyptian drawings. During this period in Egypt, art was not a separate field of culture and was not even a word used in their language. Instead, ancient Egyptian artworks played a practical and functional role in their theology and ideologies.

Contents

The History of Ancient Egyptian Artworks

Every civilization needs art to flourish. Following essential human necessities like food, accommodation, some kind of communal law, and a theological system have been met, societies start creating art, and frequently all of these processes take place more or less concurrently. Predynastic Egyptian rock carvings on rock walls depicting animals, people, and supernatural creatures signaled the beginning of this process.

Despite being primitive in comparison to later advances, these early Egyptian drawings nonetheless convey a key aspect of the Egyptian collective psyche: harmony.

Because it depicts the idealized realm of the divine, all ancient Egyptian artwork is predicated on perfect equilibrium. The art was envisioned and produced to serve a purpose, just as these gods bestowed all wonderful gifts to humankind. Egyptian sculptures and paintings were always primarily intended for practical purposes.

No matter how well a sculpture was made, its primary function was to house a deity.

Although a talisman would have been created with aesthetic attractiveness in mind, protection was the main consideration. The shapes of tomb murals, temples, and palace gardens were all designed to have a significant purpose, which was to serve as a reminder of the ephemeral nature of life and the importance of both individual and group values.

Early Dynastic Period Art (3100 – 2685 BC)

From the very beginning, Egyptian art was infused with the idea of equilibrium, which is represented through symmetry. This value is established by the Predynastic Period’s rock art and is completely evolved and perfected in the Early Dynastic Period. The Narmer Palette (c. 3200-3000 BCE), a piece of art produced to commemorate the unification of Lower and Lower Egypt under King Narmer, is considered to be the pinnacle of this period’s artistic achievement.

The tale of the great king’s triumph over his adversaries and how the gods supported and approved of his deeds are presented through a sequence of carvings on a siltstone slab fashioned as a chevron shield.

The tale of unity and the rejoicing of the monarch is pretty evident, even though some of the pictures on the palette are challenging to decipher. Across the front, Narmer, who represents the bull’s heavenly might, is depicted in a triumphant march while donning the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Two men are seen below him battling two intertwined creatures, which are frequently seen as symbolizing Lower and Upper Egypt. On the back, the gods may be seen cheering the monarch on as he defeats his opponents. These images are all expertly carved in low-raised relief. The architect Imhotep would employ this method rather successfully toward the conclusion of the Early Dynastic Period when creating the pyramid structure of King Djoser.

The structures include beautifully carved lotus blossom, papyrus vegetation, and the Djed sign in both low relief and high relief. By this time, stoneworkers had mastered the technique of producing life-size sculptures that were three-dimensional.

One of this era’s outstanding pieces of art is the statue of Djoser (c. 2670 BCE)

Art of the Old Kingdom (2686 – 2181 BC)

This ability would grow throughout the Old Kingdom of Egypt, a period marked by the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Sphinx, and ornate tomb and temple murals thanks to a powerful central government and a thriving economy. The obelisk, which was initially created in the Early Dynastic Period, was improved upon and utilized more often throughout the Old Kingdom.

Statuary remained mostly unchanging as tomb paintings advanced in sophistication.

The shape and method that were used in both the King Khufu statue (c. 2566 BCE) and the statue of Djoser from Saqqara are incredibly similar. The workmanship and attention to detail in both of these exceptional masterpieces are extraordinary.

The Old Kingdom’s art was state-mandated, meaning the monarch or a high-ranking nobleman commissioned work and set the style’s parameters.

Old Kingdom art is so identical because, even though each artist had their own style and vision, they were required to produce works that complied with the demands of their patrons. When the Old Kingdom fell and the First Intermediate Period began, this paradigm shifted.

First Intermediate Period Art (2181 – 2055 BC)

Ancient Egyptian artwork from this period has been used to support the idea that the First Intermediate Period was a period of disorder and gloom for a long time. The First Intermediate Period’s works are seen as being of inferior quality, and the lack of any large-scale construction initiatives is used to support the claim that Egyptian culture was in a state of free descent into anarchy and breakdown.

Actually, Egypt’s First Intermediate Era was a period of rapid development and cultural transformation.

Because there was no significant central government and no state-mandated artwork, the art was not of the same quality as the previous era’s. The various regions were now able to establish their own artistic visions and produce works by those visions. Art during the First Intermediate Period is not inferior to Old Kingdom art in any way; it is just different.

It is also simple to see why there were no large-scale construction projects during this era: the Old Kingdom’s dynasties had spent all of the government’s money constructing their own magnificent monuments, thus by the time of the Fifth Dynasty, there were no funds left for such endeavors. There is little data to support that the period that followed was any type of “dark age,” but the fall of the Old Kingdom after the 6th Dynasty was undoubtedly a period of uncertainty.

There were many excellent works created during the First Intermediate Period, but mass-produced art also became more prevalent.

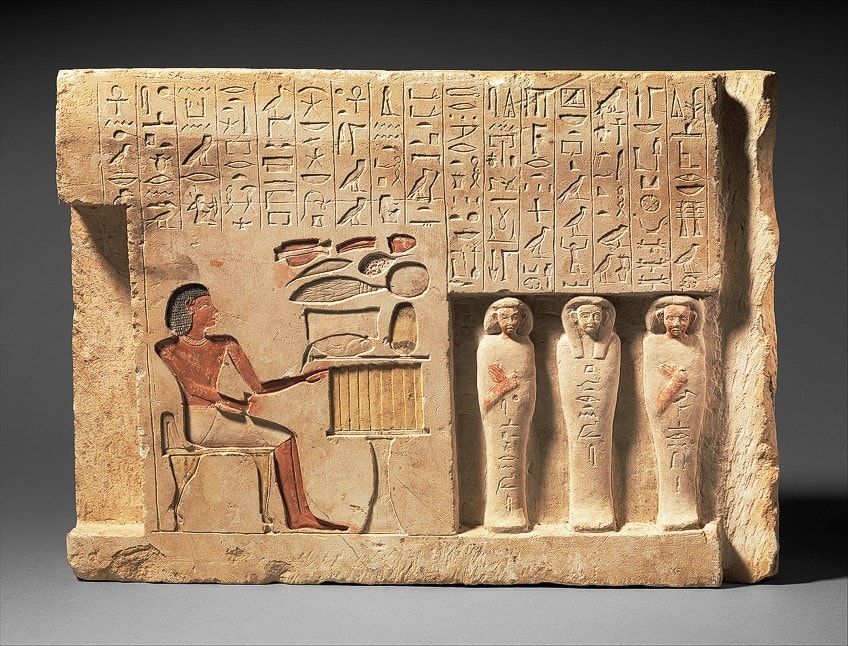

A manufacturing team now produced and painted items that were formerly created by a single artisan. These crafts included shabti dolls, pendants, coffins, and earthenware. Shabti dolls were significant funeral items that were interred with the departed and were believed to reanimate in the afterlife and take care of their obligations.

Originally constructed of stone, faience, or wood, they were mass manufactured for low-cost sales in the First Intermediate Period and primarily composed of wood. Shabti dolls were significant objects because they would let the deceased person’s soul unwind in the hereafter while the shabti performed their duties.

Art of the Middle Kingdom Period (2055 – 1650 BC)

When Mentuhotep II of Thebes overthrew the rulers of Herakleopolis and established the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, the First Intermediate Period came to an end. As Egypt’s capital, Thebes suddenly had the capacity to impose its own standards for creative creativity and aesthetics. Nevertheless, the Middle Kingdom’s authorities supported the many regional artistic movements rather than requiring that all works of art adhere to the nobility’s preferences.

Despite the high regard for Old Kingdom artwork and the clear attempts to emulate it in many instances, Middle Kingdom Art stands out for the sophisticated technique and the subjects it explores.

Most people consider the Middle Kingdom to be the pinnacle of Egyptian culture. The tomb of Mentuhotep II is an artistic creation in and of itself. It was carved out of the rocks near Thebes and flawlessly integrates with the surrounding environment to give the impression that it is an entirely organic piece.

The accompanying Egyptian paintings and sculptures, and frescoes all display a high degree of skill and, as usual, symmetry. Some of the best jewelry items in Egyptian history are linked to this period, which saw a significant increase in jewelry refinement. During Senusret II’s reign, he presented his daughter with a pendant made of fine gold wires linked to a solid gold base that has 372 semiprecious stones inlaid in it.

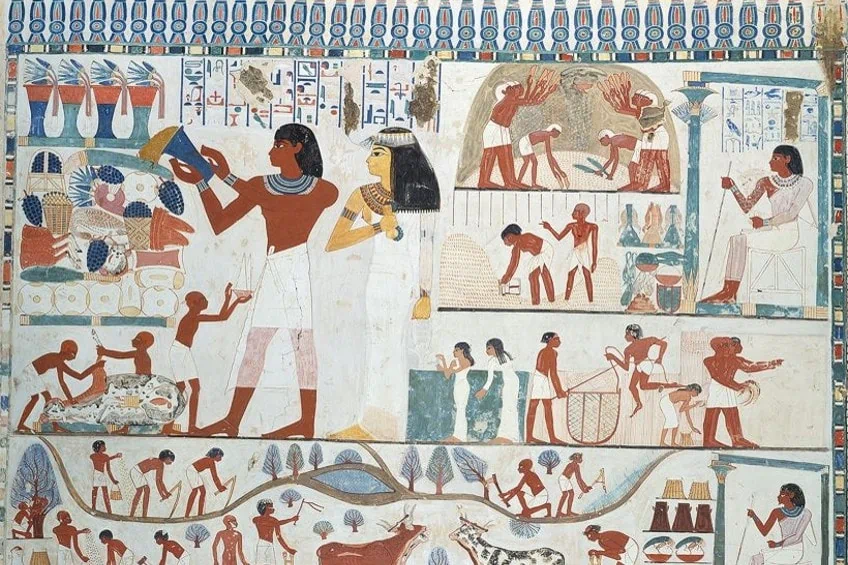

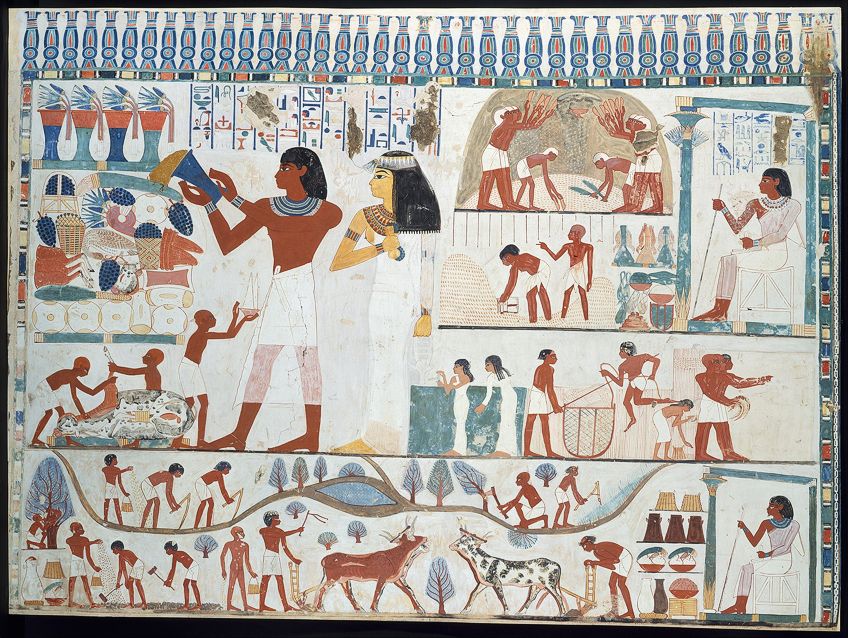

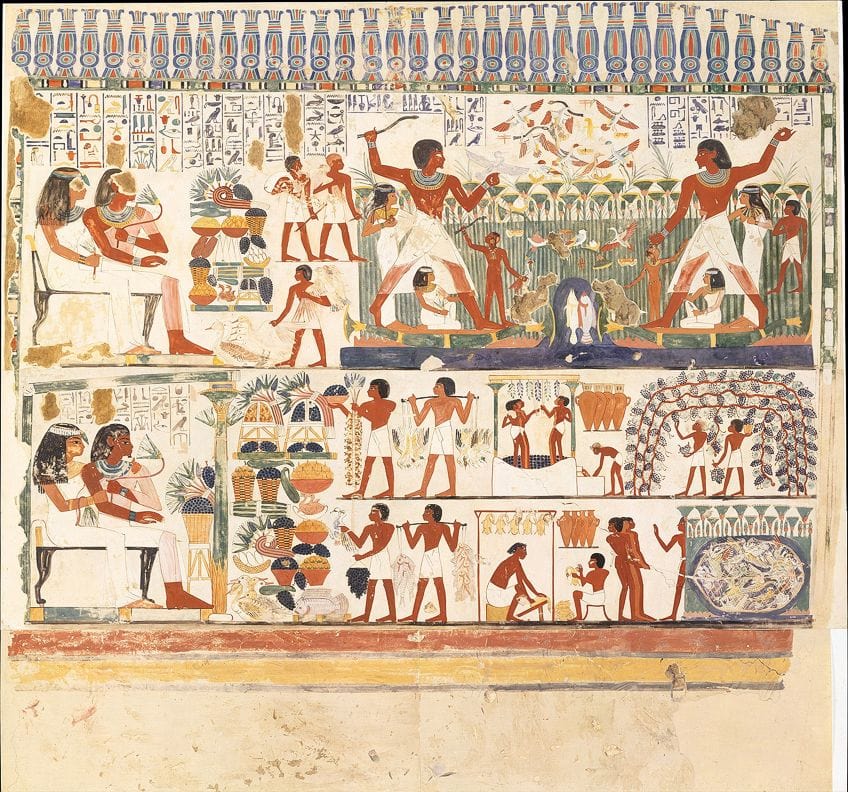

Refinement and beauty absent from most of the Old Kingdom art may be seen in the meticulous carving on the statues and busts of the kings and queens. The subject matter, however, is what makes Middle Kingdom paintings stand out the most. In comparison to previous periods, this one has the most depictions of common people.

Farmers, musicians, performers, and household life enjoy almost as much emphasis as monarchs and the divine in Middle Kingdom artwork, which continues to reflect the impact of the First Intermediate Period.

The conventional idea of the afterlife was still reflected in tomb art, but contemporaneous literature cast doubt on the traditions and advocated focusing on the one life one might be sure of—the present moment. This emphasis on earthly existence is mirrored in artwork that is less utopian and more earthy. Statuary and artwork show rulers like Senusret III as they actually were, not as idealized figures. This is shown by the consistency and accuracy of the depictions, according to scholars.

Senusret III is depicted in several artworks at various ages, occasionally seeming defeated and other times triumphant. In contrast, rulers from former centuries were usually depicted as being young and powerful. Egyptians understood that emotions are transient and that one would not want one’s immortal picture to reflect simply one point in life but the entirety of one’s lifetime, which is why their art is renowned for being emotionless.

This rule is upheld in Middle Kingdom art, which also contains stronger emotional undertones than in earlier periods.

Whatever one’s perspective of the hereafter may have been at that time, art always tends to focus on the present. The everyday joys of life on earth, such as feasting, drinking, and growing and harvesting a crop, are shown in depictions of the afterlife. The attention to detail in these pictures highlights the pleasures of earthly life, which one should enjoy to the fullest. During this period, dog collars also advance in sophistication, suggesting that hunters had more free time and paid more attention to the embellishment of everyday items.

During the 13th Dynasty, the Middle Kingdom started to disintegrate as a result of the monarchs’ complacency and disregard for state issues. The Hyksos established a sizable presence in the Delta area of the north, while the Nubians intruded from the south. The administration in Thebes gradually declined and gave way to the Second Intermediate Period when it lost all control of significant portions of the Delta to the Hyksos and was powerless to stop the rise of the Nubians.

The Hyksos either took older artworks for their temples or contracted for bigger pieces during this time, while the authorities at Thebes continued to request art albeit on a lower scale.

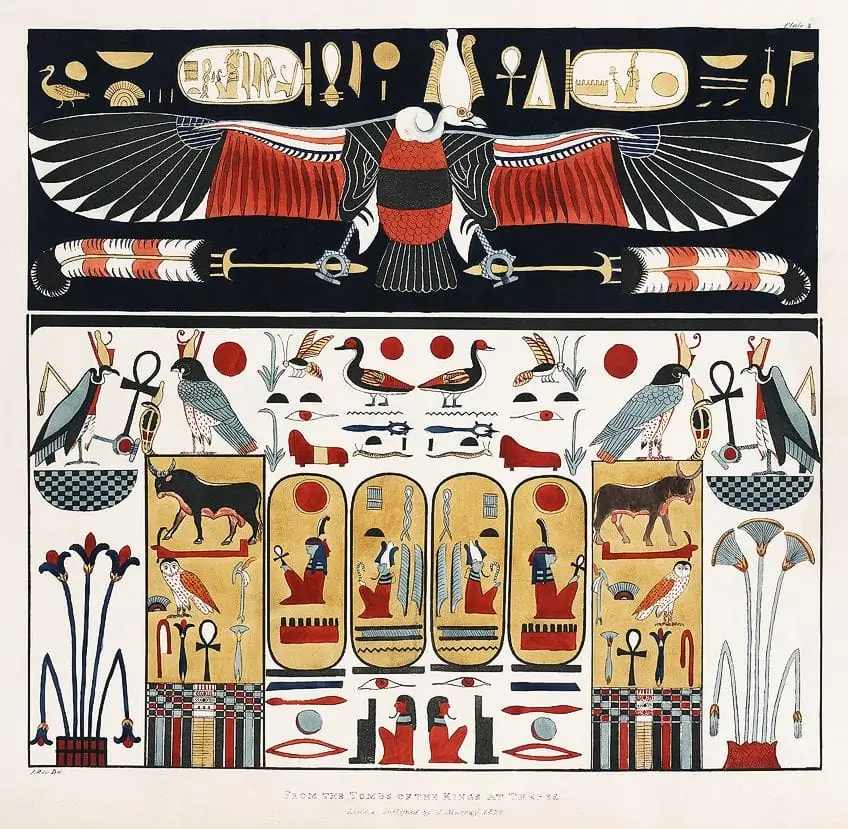

New Kingdom Artworks (1550 – 1069 BC)

The customs of the Middle Kingdom were carried on via Egyptian art throughout the Second Intermediate Period, but frequently less successfully. Thebes’ royalty had access to the greatest painters, who created works of excellent quality, while non-royal artists lacked these talents. Similar to the previous, this period is sometimes described as chaotic, and the artwork served as evidence of this.

Nevertheless, many excellent works were produced during this period; they were just on a lesser scale.

Even while the Hyksos were frequently demonized by later Egyptian scribes, they still made high-quality tomb paintings, statues, and other jewels, contributing to cultural advancement. They replicated and conserved a large number of the historical writings that are still in existence, as well as Egyptian sculptures and other artwork. Theban prince Ahmose I, whose reign marks the start of the New Kingdom, was ultimately responsible for driving the Hyksos out of Egypt.

With the most well-known kings and most identifiable art, the New Kingdom is the most well-known period in Egyptian history. The Middle Kingdom’s introduction of colossal statues began to appear more frequently at this time, the Karnak Temple and its enormous Hypostyle Hall underwent regular expansions, an increasing number of people obtained copies of the Egyptian Book of the Dead with corresponding visuals, and funerary items like shabti dolls were of greater quality. Egypt under the New Kingdom was an imperial Egypt.

Egyptian painters were exposed to many styles and methods as the nation’s borders grew, which enhanced their abilities.

Art also benefited from the Hittite metals that the Egyptians used in their weapons. Both the size and the caliber of the individual artworks spoke to the country’s affluence. Amenhotep III, the third pharaoh, erected so many structures and temples that subsequent academics gave him credit for a very lengthy rule. The Colossi of Memnon, two gigantic sculptures of the sitting ruler, are among his most famous creations.

When they were initially constructed, they were located at the entrance of the now-demolished funerary temple of Amenhotep III. The Middle Kingdom’s realism in art was revived during this period, which is referred to as the Amarna Period. Artistic representations had once more shifted in the direction of the ideal from the start of the New Kingdom. Although Queen Hatshepsut is shown accurately, most pictures of the nobles during her reign display the optimism of Old Kingdom tastes with heart-shaped features and smiles.

Modern academics have been able to accurately estimate what medical conditions the subjects in the images most likely had since the art of the Amarna era is so realistic.

This period produced two of the most well-known pieces of Egyptian art: the golden Tutankhamun death mask and the bust of Nefertiti. The wife of Akhenaten, Nefertiti, is closely associated with Egypt today because of the German archaeologist Borchardt’s discovery of her bust in Amarna in 1912 CE.

When he passed away before becoming 20 years old, Tutankhamun, Akhenaten’s son, was in the midst of undoing his father’s religious modifications and restoring Egypt to its traditional beliefs. He is primarily known for his illustrious tomb, which was found in 1922 CE, and the numerous valuables it held. The metallurgy advancements gained from the Hittites were used to create the golden mask and other metal items discovered in the tomb.

Because the Egyptians were interested in learning new methods and styles and adopting them, their art ranks among the best of any civilization.

Before the Hyksos arrived in Egypt, Egyptians regarded other countries as being uncivilized and savage, and they did not give them any special consideration. The “invasion” of the Hyksos compelled the Egyptian populace to acknowledge and utilize the contributions of others.

Later Periods (1069 – 664 BC)

The Third Intermediate and Late Periods, which are also adversely compared to the more opulent eras with powerful central authority, would go on with the acquired skills. The circumstances and the available resources had an impact on these latter periods’ styles, yet the work is still of a very high caliber. The art of this era “reflects the competing forces of heritage and modernity,” according to Egyptologist David P. Silverman.

In an effort to associate themselves with Egypt’s earliest customs, the Kushite kings of the Late Period of Ancient Egypt resurrected Old Kingdom art, while local Egyptian kings and aristocracy aimed to enhance creative depiction from the New Kingdom.

Ancient Egyptian Artwork Characteristics

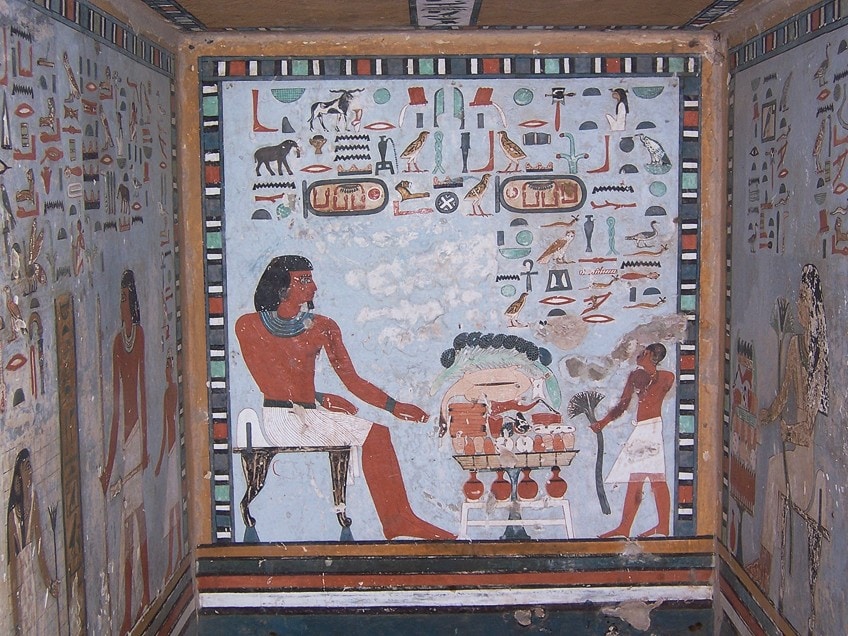

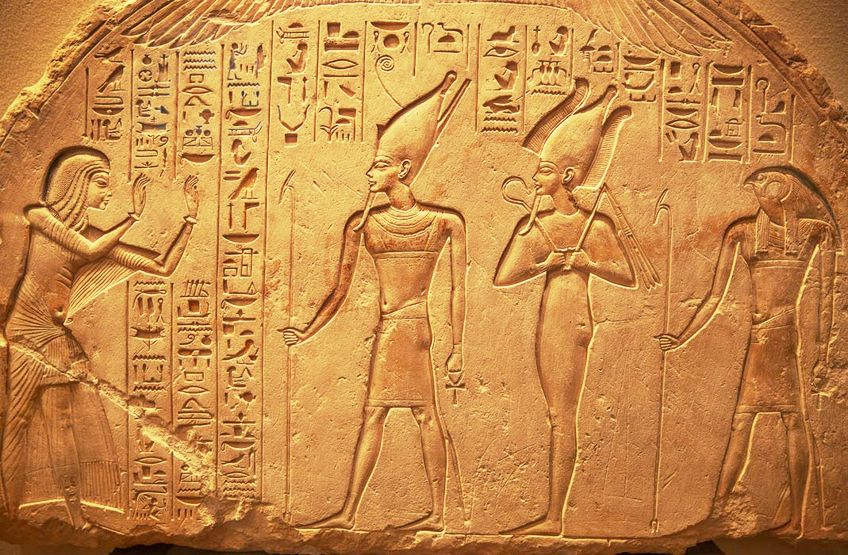

Egyptian art is renowned for its unique figure convention, which is utilized for the major characters in both relief and Egyptian paintings, with split legs (if not seated) and a head depicted from the side but a torso depicted from the front. The dimensions of the figurines are likewise uniform, extending 18 “fists” from the base to the forehead.

This may be seen in the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I, albeit lesser characters represented engaged in some action, such as prisoners and dead, do not utilize this idealized figure norm.

Traditional Traits

Other traditions cause masculine sculptures to be darker than female sculptures. The Second Dynasty sees the first highly representational portrait figures, and until the Greek invasion, little changed in terms of the idealistic features of the pharaohs or other Egyptian artistic traditions, besides the craftsmanship of Akhenaten’s Amarna and some other phases, like the Twelfth Dynasty.

Hierarchical proportions are used in Egyptian artwork, where a figure’s size denotes its relative importance.

The deities or the divine pharaoh are typically larger than other figurines, while representations of top officials or the owner of a tomb are typically smaller. Any servants, performers, animals, plants, and architectural features are typically at the smallest scale.

Anonymity and Symbolism

Rarely did ancient Egyptian painters leave their names behind. The majority of the time, Egyptian art was created collectively, which contributes to its anonymity. So, when the craftsmen have established the size of the sculpture, they all go home to build the pieces that they have chosen, according to Diodorus of Sicily, who visited and lived in Egypt. Egyptian art was heavily influenced by symbolism, which was crucial in creating a feeling of order.

For instance, the pharaoh’s regalia symbolized his ability to uphold order. In Egyptian art, animals were also incredibly meaningful creatures.

There were some expressive hues. The four primary color groups of the ancient Egyptians were black, white/silver, green/blue, and red/orange/yellow. For instance, the color blue represented life, birth, and the Nile’s sustaining waters. The colors of vegetation and hence of renewal were blue and green. Osiris might be shown as having green skin; during the 26th Dynasty, green paint was frequently applied on coffin faces to promote rebirth. The prevalence of turquoise and faience in burial gear can be attributed to this color symbolism.

Similar to how black portrayed the fertile alluvial soil of the Nile, from whence Egypt sprung, black was also associated with fertility and renewal. As a result, the monarch frequently appeared with dark skin in statues depicting Osiris.

Additionally connected to the afterlife, black served as the hue of burial deities like Anubis. Due to its supernatural appearance and connections to rare elements, gold was a sign of divinity.

The ancient Egyptians also considered gold to be “the flesh of the gods.” The Egyptians also referred to silver as “the bones of the deity,” and dubbed it “white gold.” Yellow, orange, and red were ambiguous hues. Naturally, they were linked to the sun, and red stones like quartzite were preferred for royal statues that emphasized the solar qualities of royalty. Similar metaphorical connotations apply to carnelian in jewelry. Important names were inscribed in red ink on papyrus texts. Additionally, red was connected with Set since it was the color of the deserts.

Types of Ancient Egyptian Artwork

Egyptian art is fairly traditional; over time, the art form altered little. The art that has survived largely comes from tombs and monuments, providing more insight into ancient Egyptian ideas about the afterlife. Now let’s examine the most well-known kinds of Egyptian art: Egyptian paintings and drawings, and Egyptian sculpture.

Egyptian Sculpture

The massive sculpture of ancient Egypt’s tombs and temples is widely known, yet polished and delicate little pieces abound. The Egyptians utilized the sunk relief style, which is best observed in the sunshine to highlight the contours and figures with shadows. The characteristic position of standing statues facing forward, one foot in front of the other, was beneficial to the piece’s equilibrium and power. This unique stance was utilized early in Egyptian art history and far into the Ptolemaic period while sitting sculptures were also frequent.

Other deities are significantly less prevalent in huge sculptures, particularly when they depict the pharaoh as another deity; nonetheless, the other deities are regularly shown in Egyptian paintings and reliefs.

The famed series of four huge sculptures outside Abu Simbel’s main temple each depict Rameses II, a standard pattern, but here extremely big. The majority of bigger sculptures remained from Egyptian tombs or temples; gigantic statues were erected to symbolize gods, pharaohs, and their queens, often for open areas within or outside temples.

The huge Great Sphinx of Giza was never duplicated, although roads lined with very big sculptures of sphinxes and other animals were part of several temple complexes. The most important cult image of a deity at a temple, normally kept in the naos, was a very modest boat containing an image of the god, supposedly made of precious metal – none of them are believed to have remained. The notion of the Ka statue was thoroughly established by Dynasty IV. As a location for the Ka fraction of the soul to relax, these were placed in tombs.

As a result, there are many less traditional statues of wealthy supervisors and their wives. Many of these are made of wood because Egypt is one of the few locations in the world where the environment allows the wood to last for millennia.

Although it is still debatable whether or not there was any true portraiture in ancient Egypt, the so-called reserve heads, which are simple, hairless heads, are very lifelike. Small replicas of slaves, animals, structures, and other items like boats that the deceased would have needed to maintain his way of life in the afterlife might also be found in early graves. The bulk of wooden sculpture, however, has likely been burned or lost to deterioration. Small figurines of gods or their animal embodiments are highly prevalent and may be found in widely used objects like earthenware.

There were also a lot of little carved items, including toys, utensils, and deity figures. Although painted wood was the most frequent material used for these, alabaster was utilized for more expensive alternatives of them. Small replicas of animals, slaves, and goods were frequently buried in tombs to cater to the afterlife. When making sculptures, extremely rigid guidelines were followed, and each Egyptian god’s look was restricted by a set of regulations.

For instance, the deity of burial rituals was to be depicted with a jackal’s head, while the sky deity was to be depicted with a falcon’s head.

These norms were abided so strictly that, over the course of 3000 years, the aesthetic of statues barely changed. Artistic works were graded according to their adherence to these conventions. These customs were used to demonstrate how the figure’s ka was timeless and ageless. The distinction between males and women in ancient Egyptian art was a frequent relief.

Women were rarely portrayed in their older, more mature selves; instead, they were frequently portrayed in youthful, idealized forms. Either an idealized or more realistic portrayal of men was presented. Men are frequently depicted in sculptures as having aged; for them, growing older was a good thing, in contrast to women, who are always depicted as youthful.

Egyptian Drawings and Egyptian Paintings

Not every Egyptian relief was painted; lesser-known pieces found in tombs, temples, and palaces were simply painted on a flat surface. Whitewash or, if the texture was rough, a coating of coarse mud plaster was applied, followed by a coating of smoother gesso; some finer limestones, however, may be painted right away. The majority of the pigments were mineral-based, intended to resist intense sunshine without fading.

Although egg tempera and a number of resins and gums have been proposed, the binding substance employed in painting is still unknown.

True fresco, which is painted over a thin coating of wet plaster, was obviously not employed. Instead, in a technique known as fresco a secco in Italian, the paint was put on dry plaster. Many paintings that had some access to the elements have lasted exceptionally well, however, those on totally exposed walls seldom have. This is likely due to the protective varnish or resin that was typically applied after painting. Similar painting methods were frequently used on little items, such as wooden statuettes.

Due to Egypt’s unusually dry atmosphere, several ancient Egyptian artworks have been preserved in tombs and even temples. The paintings were frequently created with the idea of giving the dead a comfortable afterlife. The topics ranged from trips through the afterlife to guardian deities bringing the dead to the underworld gods. Some tomb murals depict the deceased’s pursuits during their time on earth, pursuits they desired to continue in eternity. The Book of the Dead was interred alongside the deceased starting in the New Kingdom. It was seen as crucial for introducing the afterlife.

Egyptian paintings sometimes depict people or animals from both the front and the side at the same time.

However, in general, Egyptian painting did not establish a perception of depth, nor are backdrops nor a feeling of visual viewpoint found, with the figures instead varying in size with their significance rather than their position. Egyptian paintings depicting hunting and fishing sequences can have vibrant close-up landscape backgrounds of grasses and water.

Examples of Egyptian Sculpture and Paintings

To comprehend ancient Egyptian art, one must consider it from their point of view. Many Egyptian images are rather static, sometimes formal, bizarrely abstract, and frequently blocky, which has occasionally led to unflattering comparisons with later, far more “naturalistic,” Greek or Classical art. However, compared to these subsequent societies, the Egyptians’ use of art was very different.

While admiring the sparkling artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb, the exquisite reliefs in New Kingdom tombs, and the tranquil beauty of Old Kingdom statues today, it is crucial to keep in mind that the bulk of these creations was never meant to be seen.

Head from a Statue of King Amenhotep I (c. 1525–1504 B.C.)

| Date of Completion | c. 1525 – 1504 B.C. |

| Medium | Painted sandstone |

| Dimensions (cm) | 20 (height) |

| Current Location | The Met Museum |

At the start of the Middle Kingdom, Mentuhotep II constructed the temple at Deir el-Bahri, to which King Amenhotep made his own modifications. Most significantly, he added a row of mummiform sculptures of himself on the procession route that the deity Amun’s image was taken down once a year toward Mentuhotep’s shrine.

These sculptures are notable for their distinctive faces in addition to their intimidating original height of more than 2.5 meters.

This portion of a face with a bulbous nose and cleft chin is from a particularly aesthetically accomplished instance of the series: a real picture of a specific individual who was king of Egypt. This head’s profile is very similar to one on a relief of the same king. Compare the small upper lip and the nose’s contour in particular, which are nearly identical in both artworks. Images of an Egyptian ruler were presumably based on an officially sanctioned resemblance that blended recognized traits into an idealistic image of the ruler in question.

These works, one in two dimensions and the other in three, are identical to one another.

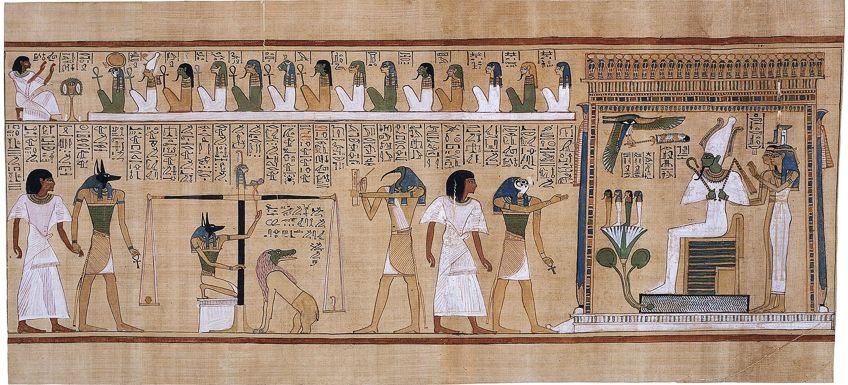

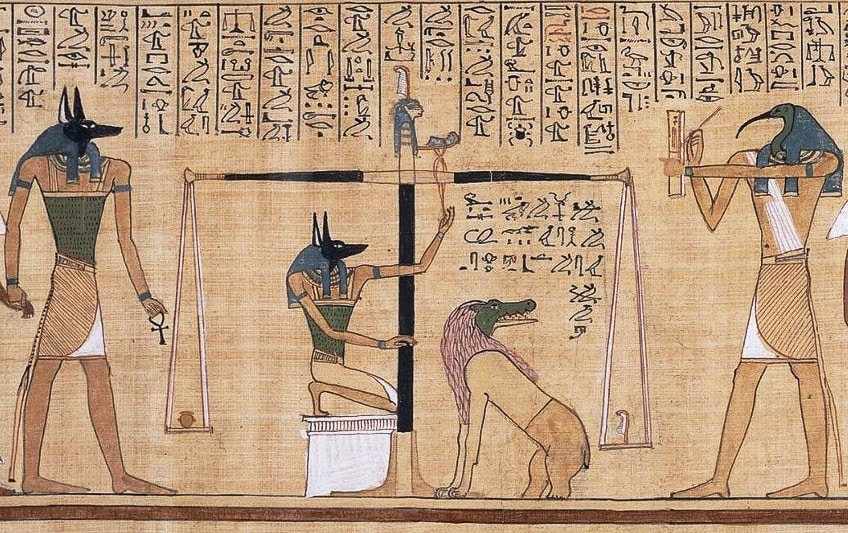

The Book of the Dead (c. 1275 B.C)

| Date of Completion | c. 1275 B.C |

| Medium | Pigment and ink on papyrus |

| Dimensions (cm) | 45 x 90 |

| Current Location | British Museum, London |

The Book of the Dead was a component of a legacy of funerary literature that also included the older Pyramid Texts, which were painted onto items rather than written on papyrus. It was put in the burial chamber of the departed. The spells in the book date back to the third millennium BCE and were taken from these earlier writings. Later on in Egyptian history, during the Third Intermediate Period, further spells were written.

As with the spells from which they descended, some of the spells that make up the Book were still written independently on tomb walls and sarcophagi.

The religious and mystical texts found in the remaining papyri vary greatly in content and artwork. Some individuals appear to have ordered their own versions of the Book of the Dead, presumably selecting the spells they believed would be most helpful in assisting them in their own ascension to the afterlife.

The Book of the Dead was frequently written on a papyrus scroll in hieratic or hieroglyphic character, and it was frequently illustrated with scenes showing the departed and their ascension into the afterlife.

The Goddess Isis and her Son Horus (c. 330 – 30 B.C)

| Date of Completion | c. 330 – 30 B.C |

| Medium | Faience |

| Dimensions (cm) | 17 x 5 x 7 |

| Current Location | The Met Museum |

A potent symbol of regeneration for the ancient Egyptians is the figure of the goddess Isis nursing her child Horus. This important symbol was carried into the Ptolemaic era and was eventually transported to Rome, where the goddess’ religion was created.

The history of pharaonic Egypt and the Ptolemaic period’s creative aesthetic are combined in this piece of faience sculpture.

The hieroglyph for the goddess’ name, the throne, is visible on her head. She also sports a vulture headdress that is often worn by queens and deities. Horus is shown in a hairless state with a single strand of hair on the right side of his head, according to old standards for denoting infancy.

For thousands of years, people have been captivated by ancient Egyptian artwork. Egyptian skills impacted the early Greek and later Roman painters, and their work would affect other cultures up to the current day. Many painters from later eras are well-known, but those from Egypt are entirely unknown, and for an intriguing reason: their art was useful and made with a purpose in mind, as opposed to subsequent art, which was created for purely aesthetic reasons. While art done for pleasure, even when commissioned, allows for better expression of the artist’s vision and, as a result, acknowledgment of a particular artist, utilitarian art is art made on-demand and belongs to the individual who requested it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Characterizes Ancient Egyptian Artwork?

In Egypt, art is known for its distinctive figure convention, which has split legs, a head painted from the side, but a torso painted from the front, for key figures. The figurines are consistent in size, measuring 18 fists from the base to the forehead. This may be observed in the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I, while less important individuals, such as slaves and the deceased, who are depicted in some kind of activity, do not follow this idealized figure pattern.

What Was the Function of Ancient Egyptian Artwork?

In Egypt at this time, art was neither a distinct cultural discipline nor a word in the native tongue. Instead, the beliefs and ideology of the ancient Egyptians were influenced by the artwork they produced. For a society to flourish, it requires art. After basic human needs like food, shelter, some form of social law, and a religious framework have been satisfied, civilizations begin to produce art, and typically all of these processes occur more or less simultaneously.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Egyptian Art – Discover the Influence of Ancient Egyptian Artwork.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 2, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/egyptian-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 2 August). Egyptian Art – Discover the Influence of Ancient Egyptian Artwork. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/egyptian-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Egyptian Art – Discover the Influence of Ancient Egyptian Artwork.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 2, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/egyptian-art/.