Egyptian Artifacts – Treasures of the Nile

Ancient Egyptian artifacts have served as some of the oldest artistic items created by human beings, and so they are worth examining in some level of detail. This article will discuss ten of these ancient artifacts, along with descriptions of what they depict and the history of the items in question. Keep reading if you want to learn about a few Ancient Egyptian artifacts and what makes them so special!

A Look at Ancient Egyptian Artifacts

The Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for thousands of years and remained one of the political and military powerhouses of the ancient world. Throughout the time in which this ancient civilization developed and grew, the people of that civilization created beautiful works of art.

We are going to examine a few of these Ancient Egyptian artifacts throughout the remainder of this article, so keep reading to learn a lot more.

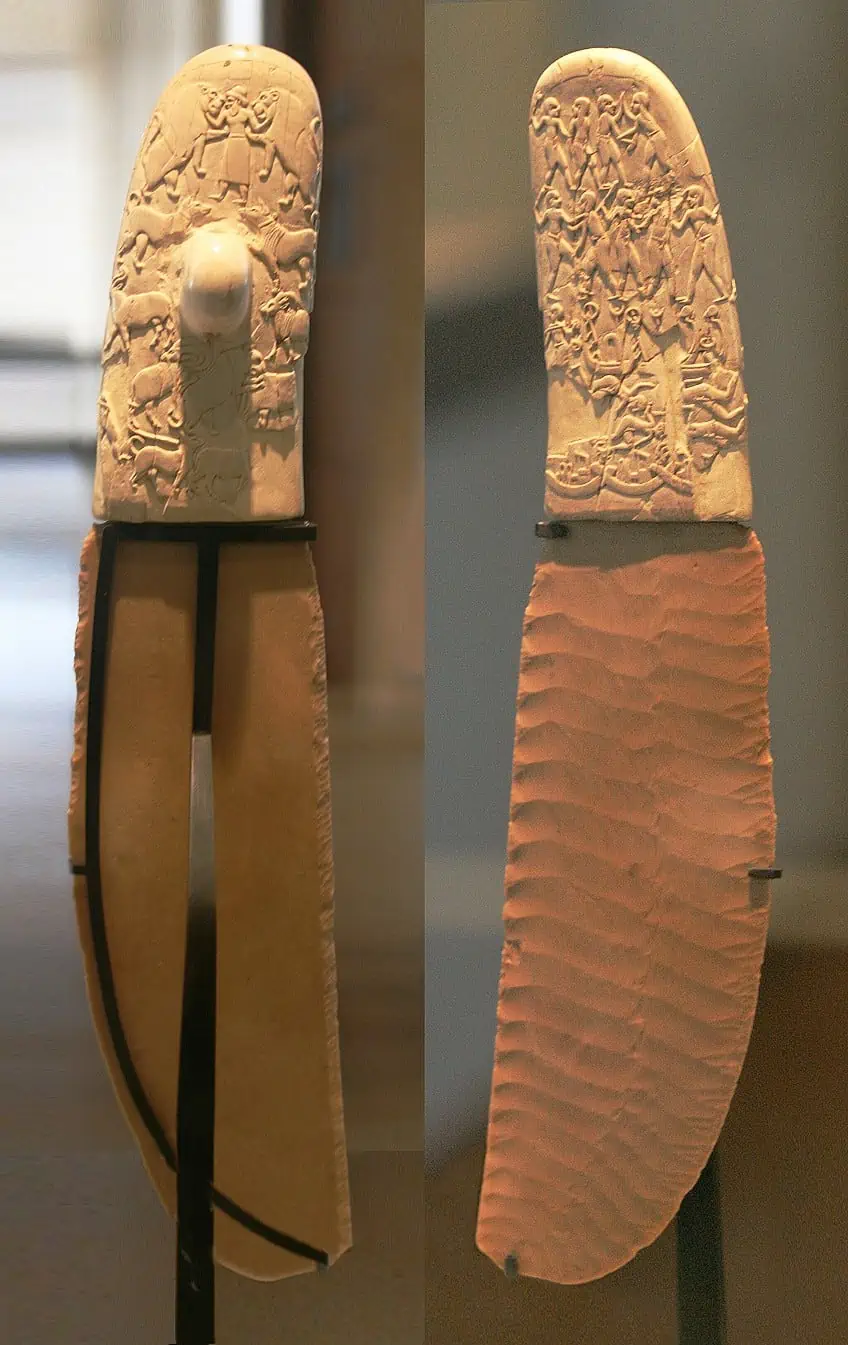

Gebel el-Arak Knife (3500 – 3200 BCE)

| Date | 3500 – 3200 BCE |

| Materials Used | Ivory and flint |

| Function | Knife |

| Dimensions (cm) | 18.8 x 5.7 x 0.6 |

The Gebel el-Arak Knife is one of the oldest Egyptian artifacts at over 5,000 years old, and from the designs that adorn the blade, it appears to have significant influence from Mesopotamian sources. The knife itself is made of a combination of ivory and flint, neither of which were uncommon materials at the time for similar creations. Ivory has especially been used for an incredibly long time for knives and other items for its versatility.

The knife, like many Ancient Egyptian relics, was incredibly mishandled over the course of its existence.

It was sold to the Louvre in 1914, but before that, it was handled by someone who supposedly found it in Gebel el-Arak, and the blade is named after it because of that, but more recent scholarship has stated that it was more likely to have come from Abydos. The lack of definitive records is quite indicative of the kinds of looting that occurred throughout much of colonial history with regard to relics. While the Gebel el-Arak Knife may not be one of the most famous Egyptian artifacts, it certainly is a stunning example of the kind of craftsmanship that was available this long ago in Ancient Egypt.

The flint that was used is called chert, and it’s a yellowish color and very common in the country, and it gives the blade the unique color that it now possesses. The handle of the knife was made from ivory, specifically ivory from an elephant (although it had, at first, been believed that it was from the tooth of a hippopotamus). It was carved from the axis of the tusk as there is a darkened center, and the handle is also full of engravings.

The engravings depict a battle scene with various animal figures, especially those of more mythological orientation.

Bull Palette (3200 – 3000 BCE)

| Date | 3200 – 3000 BCE |

| Materials Used | Greywacke |

| Function | Palette |

| Dimensions (cm) | 26.5 × 14.5 |

The Bull Palette is not a complete item. Instead, this Ancient Egyptian relic is only part of a larger palette that is now lost. The palette was made of greywacke, a material commonly used at the time, and the artifact depicts a carved relief image. What was this artifact used for though? Well, it was a makeup palette. These are used for the preparation of cosmetics and, in this case, for the grinding up of cosmetic materials so that they could be applied.

Most contemporary palettes don’t have art on them and are generally plain sheets of metal or plastic, but that was not the case in this particular instance.

There are carvings on either side of this now-broken palette, which does somewhat beg the question of how it was used for precise application, but that may remain a mystery. It does have a beautiful aesthetic regardless of its somewhat weaker functionality. The carved artifact depicts a fortified city-state and a number of animalistic images, most notably the bull iconography on the sides. The bulls face one another from their respective portions of the Egyptian artifact.

The reverse side of the palette depicts a battle between a warrior and a bull, and the bull is winning in that particular scenario. These were somewhat common images in other similar Egyptian artifacts. For instance, similar iconography can be seen on the Narmer Palette.

This indicates the reusable nature of iconography of this nature and how it clearly played a major role in early Egyptian society.

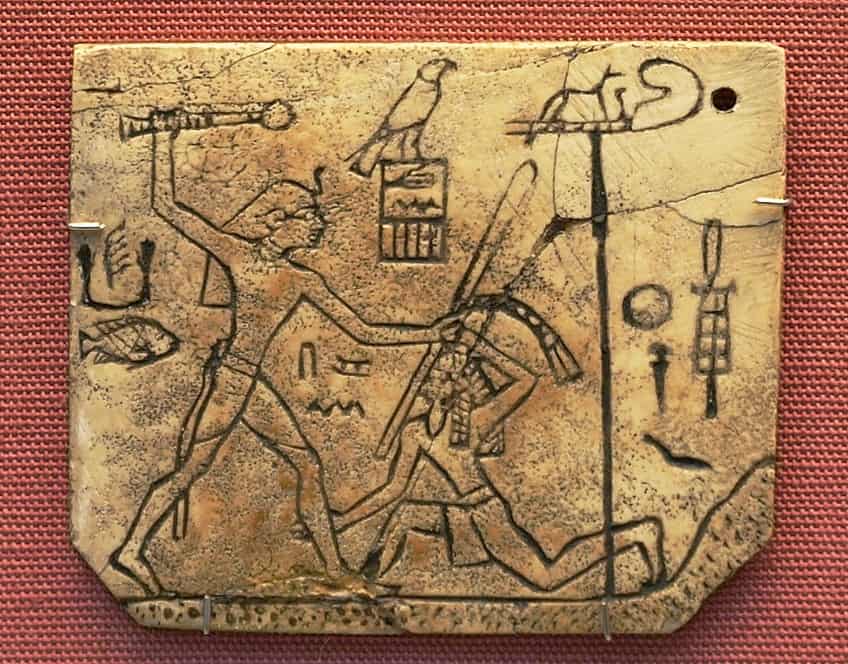

MacGregor Plaque (2985 BCE)

| Date | 2985 BCE |

| Materials Used | Ivory |

| Function | Plaque |

| Dimensions (cm) | 4.5 x 5.4 x 0.2 |

The MacGregor Plaque is quite a peculiar Egyptian artifact. It is a plaque that was made of carved ivory and it isn’t very big at all. This small artifact depicts the Egyptian Pharaoh Den from around 2985 BCE. He is depicted wearing a loincloth, his headdress (complete with snake iconography), and an animal tail that descends from his person. The king is also depicted with a raised right hand that wields a mace and the left-hand holds an enemy down by their hair.

It’s a rather violent image that depicts the king as a war-like ruler.

The thing that makes this tiny plaque particularly strange is where it came from. It came from the pharaoh’s sandal. It no longer rests on the king’s sandal and is instead situated within the British Museum, a place that often deftly answers the question: Which museum has the most Egyptian artifacts? Because the British Museum has been collecting these items for a very long time.

This is another of the oldest Egyptian relics currently on display, and it is also a very interesting piece to have analyzed because it contains the earliest known example of the long headdress design that is known as the khat-head-dress.

So, this is an important item for further understanding some of the history of the Ancient Egyptian civilization and its customs.

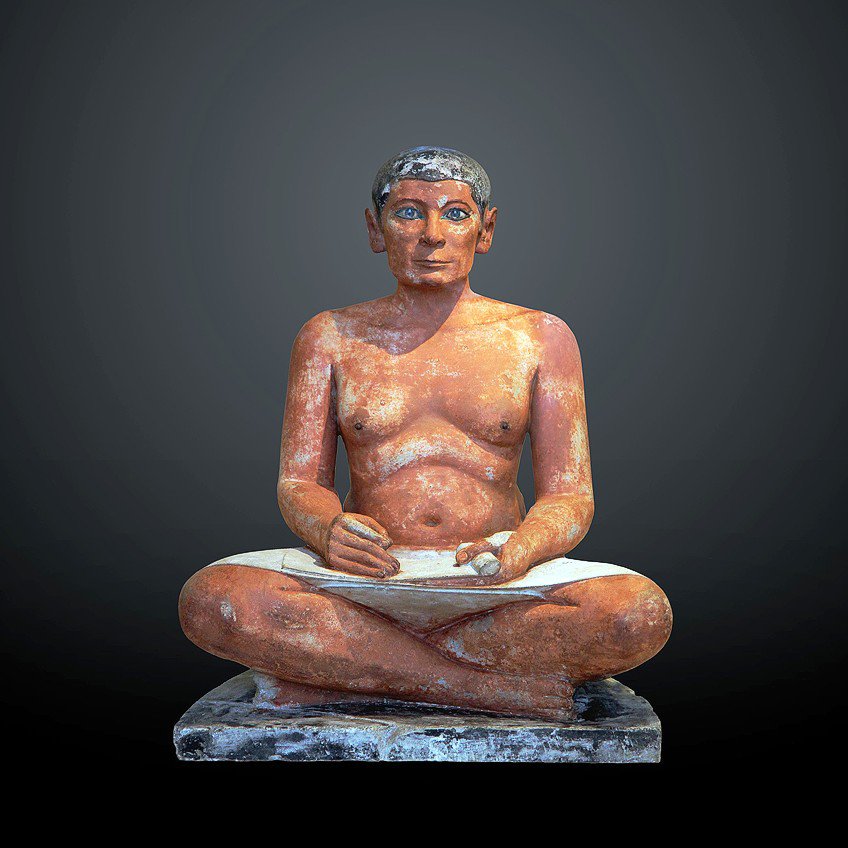

The Seated Scribe (2450 – 2325 or 2620 – 2500 BCE)

| Date | 2450 – 2325 or 2620 – 2500 BCE |

| Materials Used | Limestone |

| Function | Figurine |

| Dimensions (cm) | 53.7 × 44 × 35 |

The Seated Scribe is a small figurine that depicts an unknown figure who is most likely a scribe. It was discovered in Saqqara but, thanks to record-keeping issues, the precise discovery location has not been properly documented. The original excavation journal has also been lost, so there is even less information known about this item than there ordinarily should have been.

The Seated Scribe is among the oldest Egyptian artifacts from the Old Kingdom in Egypt, and the depiction of the scribe is of considerable interest for several reasons.

It was made from limestone, and meticulously painted, and its eyes are especially fantastic in their general depiction and artistry. The figure is holding a half-rolled papyrus scroll as his face watches whoever comes near. The face is especially detailed, and his eyes are of special interest. The eyes are made using white magnesite that has been inlaid with a polished rock crystal, and the paint is naturalistic to depict him as he may have truly been.

They stare outwards with an attentive appearance. The eyebrows were also carefully designed using a dark paint. Another interesting feature is that this depicted scribe is slightly overweight, and as was common in many ancient civilizations.

The image of a person as overweight indicated that they were wealthy to some extent and that they did not need to engage in the kind of physical labor that was expected of the vast majority of citizens.

William the Faience Hippopotamus (1961 – 1878 BCE)

| Date | 1961 – 1878 BCE |

| Materials Used | Quartz |

| Function | Statuette |

| Dimensions (cm) | 11.2 × 7.5 × 20 |

William the Faience Hippopotamus is a hippo statuette made of faience, a kind of quartz that was often used for similar designs. The statuette is currently held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (commonly known as the Met), which, like the British Museum, is a good contender for a location with many ancient artifacts not from the Americas. The statuette has even become a mascot of sorts, albeit in an unofficial capacity, for the museum. The statuette itself was created at some point in the Middle Kingdom and is not technically an example of pottery as there is no clay in its design, but it was created and polished similarly so many may instinctively label it a form of pottery even though that is not technically true.

The striking blue aesthetic of the little hippo would have once adorned a tomb from the Middle Kingdom as it was an item that was commonly found in funerary settings.

One of the reasons that this particular item may be labeled a form of pottery is because the methods used to craft it are reminiscent of pottery designs, but the kind of materials used was far more durable and valuable than any ordinary kind of clay-based pottery. This item, because of its status within the MET, is definitely one of the most famous Egyptian artifacts, but we have still not explained one thing about it: what’s with the name?

This statuette is named William, and William is generally not a name that one associates with Ancient Egypt in any capacity. Well, the name comes from Captain H. M. Raleigh, who wrote an article in 1931 that included a discussion about the item, and in it, he stated that his family referred to it as William.

So, the name has simply stuck around for years even though there were no Williams in Egypt.

Chair of Reniseneb (1450 BCE)

| Date | 1450 BCE |

| Materials Used | Wood, ivory, and ebony |

| Function | Chair |

| Dimensions (cm) | 86.2 tall |

The Chair of Reniseneb is an Ancient Egyptian chair. We tend to think that ancient cultures did not have some of the simple items that we now possess, but this 3,500-year-old chair would beg to differ. The chair has managed to survive through many thousands of years despite being made of wood, and we also know that this chair specifically belonged to a scribe named Reniseneb because his name is carved into it.

Nowadays, we tend to consider it a joke to “put our names on it”, but that ancient policy has aided us in more recent years.

The chair is made from a combination of wood, ebony, and ivory, and it is also believed that the more detailed image it now projects is a more recent one. Additions and alterations were made to the chair over the centuries to make it far more ornate and to add the name of the scribe in question. In addition, the chair is the oldest existing version of its kind from Ancient Egypt.

The seat of the chair is not part of the original though and is instead a replica made from the same kind of material as the original. However, while wood can be made to last thousands of years, the same is typically not true of woven reeds.

So, it naturally decayed over time and has since been restored.

Nefertiti Bust (1345 BCE)

| Date | 1345 BCE |

| Materials Used | Limestone and stucco |

| Function | Bust |

| Dimensions (cm) | 48 tall |

The Nefertiti Bust is definitely one of the most famous Egyptian artifacts. It is a bust of the eponymous queen as she gazes outwards at whoever is nearby. It has been copied for centuries as a famed icon of Egypt and a representation of ancient women. It is also a far more naturalistic form than some of the older forms of art from the country.

It, therefore, reveals a change in the general design principles of the country from when it was designed.

So, if you have ever asked a question like, what can we learn from Ancient Egyptian artifacts?, this is your answer. The bust is made of limestone and covered in layered stucco that has produced a symmetrical face complete with paint. The eyes are especially prominently displayed as they were inset with quartz.

The use of the past tense “were” in the previous sentence is because one of the eyes is missing its gemstone. However, the loss of a portion of this relic simply shows the kind of care and attention that items of this nature require if they have any hope of surviving through the ages without entirely coming apart.

Anubis Shrine (1341 – 1323 BCE)

| Date | 1341 – 1323 BCE |

| Materials Used | Wood, gold, silver, and obsidian |

| Function | Burial equipment |

| Dimensions (cm) | 273.5 x 63.7 x 60 |

The Anubis Shrine was one component of the burial objects that were found within the tomb of Tutankhamun. While this statue may not be as famous as the next item on this list, it has become an immensely prominent item in the emulated artworks that came from many of these ancient artworks.

The statue is both quite long, but also mostly intact at the time that it was found by Howard Carter, the famous archaeologist that uncovered the Tomb of Tutankhamun.

The item was within the tomb as a guardian figure to watch over the pharaoh’s body within. It is made of wood but painted mostly black, although some of the other elements make use of different materials. The eyes have gold, the claws have silver, and so on. The jackal image is an animalistic representation of the Egyptian god of death, Anubis, and he had a central place in Egyptian burial rites and practices.

This item is also, famously, the origin of the “curse of the pharaohs” that inspired so many pieces of later media. The inscription on this statue warned those who would disturb the tomb that they would suffer a curse.

The myth went on to influence movie monsters like the early versions of The Mummy.

Mask of Tutankhamun (1323 BCE)

| Date | 1323 BCE |

| Materials Used | Gold, lapis, carnelian, turquoise, and obsidian |

| Function | Funerary mask |

| Dimensions (cm) | 54 × 39.3 × 49 |

The Mask of Tutankhamun is most probably the most famous Egyptian artifact to have ever been uncovered. It was uncovered, along with the abovementioned statue of Anubis, in the Tomb of Tutankhamun. It was used as the funerary mask of the young pharaoh and is one of the most stunning examples of Egyptian art. It was made to resemble Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and it is inlaid with various semi-precious stones and covered in gold leaf.

It is part of a long tradition of Egyptian funerary masks, such as the Grave Mask of King Amenemope.

This particular funerary mask also contains an ancient spell on the reverse side of the item, and the spell is taken directly from the Book of the Dead, which was an ancient Egyptian text. The funerary mask does not exist within its original form any longer though, as restoration needed to be done on the item, such as restoring the braided beard that fell off the item at some point during its long existence within the sarcophagus in which it was found.

The Mask of Tutankhamun has remained an enduring image of Ancient Egypt and one of the most famous ancient artifacts from any civilization. Even those who have never paid attention to ancient artifacts will likely know this particular iconic image.

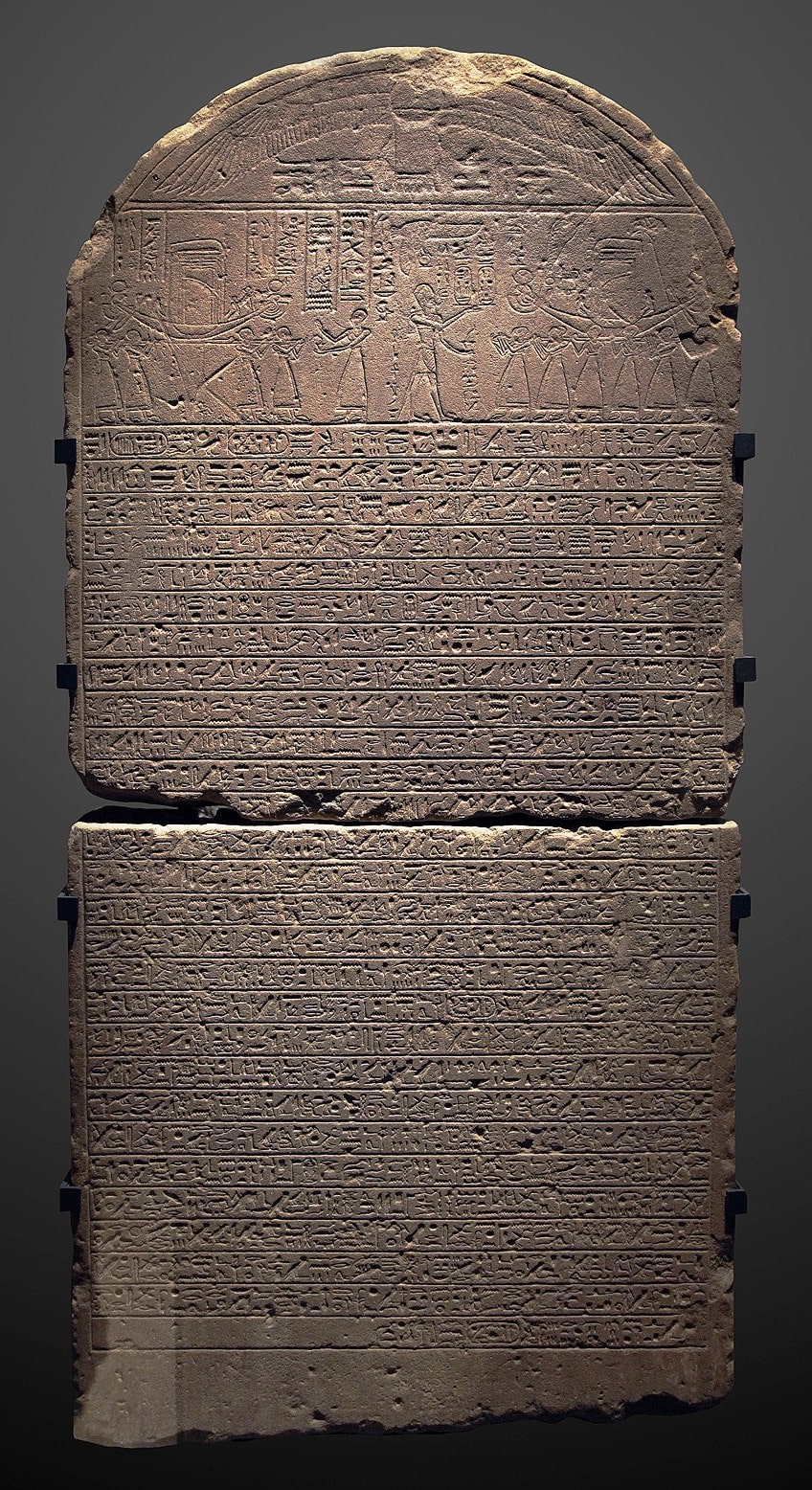

Bentresh Stele (525 – 300 BCE)

| Date | 525 – 300 BCE |

| Materials Used | Sandstone |

| Function | Stela |

| Dimensions (cm) | 222 x 109 |

The Bentresh Stele is an ancient stele made from sandstone that tells a story. It may not be one of the most famous artifacts from Ancient Egypt, but it has aided us in understanding some of the oldest tales told by this civilization. The story in question concerns the character of Bentresh, the daughter of the Prince of Bakhtan.

There are many debates over the exact age of the item, but it has gone on to be an influential piece of narrative art within the Ancient Egyptian tradition.

There are many theories about the exact origins and purposes of the text, but it may have been a way to reminisce about the ancient days of the Egyptian civilization or it may have been a more fanciful tale meant to glorify a certain period. We cannot know for certain, but the text and the stele have remained standing to this day.

We have come to the end of our discussion about Ancient Egypt artifacts. We have looked at ten different artifacts from Ancient Egypt in an attempt to show the kind of craftsmanship and ingenuity that was on display in Ancient Egyptian design. Hopefully, these ten items have revealed a few interesting things about Ancient Egyptian artifacts. So, all that’s left for us to do is wish you a great day/week/month ahead!

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Ancient Egyptian Period?

The Ancient Egyptian period took place over an immensely long period of time. This period of time began in predynastic times, long before there was a single king that presided over this civilization, from about 5500 BCE. The Early Dynastic Period began in 3150 BCE and progressed through a variety of kingdoms led by various groups and individuals until the entire region was eventually conquered by Alexander the Great, which started a period of Greek rule from 332 BCE. It was later taken by the Romans in 30 BCE, and that may have be the actual end of Ancient Egypt as we know it.

What Is the Most Famous Egyptian Artifact?

The Mask of Tutankhamun is probably the most famous Egyptian artifact, and as far as Ancient Egypt artifacts go, it has practically become a symbol of this ancient civilization. It is a golden funerary mask that was buried with the boy-pharaoh himself and remained buried for about 3,000 years. Funerary masks, like the Grave Mask of King Amenemope, were common for Ancient Egyptian rulers as aids in their journey through the afterlife.

Why Did the Ancient Egyptian Civilization End?

The Ancient Egyptian civilization came under the rule of the Ancient Greeks via Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, but the Egyptian culture predominantly remained as it was. So, this period of Greek rule could be considered a continuation of the Ancient Greek culture. Ancient Egypt would then fall to the Romans in 30 BCE, who were less willing to allow differences within their civilization. This continued until the 7th-century occupation, loss, and re-occupation by Islamic forces. It has remained a predominantly Islamic country ever since, so any of these eras could be seen as the end of the Ancient Egyptian civilization.

What Can We Learn from Ancient Egyptian Artifacts?

There is much that we can learn from the artifacts of any culture. We can learn about their customs, religious beliefs, funerary traditions, writing styles, and a lot more. Ancient artifacts from around the world have allowed us, through archaeological analysis, to understand the civilizations on which our own is built. We all came from the ancients, and so understanding them is to understand our own origins.

Which Museum Has the Most Egyptian Artifacts?

The best contender for the most ancient artifacts, in general, is likely the British Museum. In terms of artifacts from Egypt, it contains over 100,000 unique items, but there are also other collections that supplement that number, like the Wendorf Collection of Egyptian and Sudanese Prehistory, which was donated in 2001. That collection contains over six million artifacts. So, the British Museum probably has more than anywhere else in the world.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Egyptian Artifacts – Treasures of the Nile.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 10, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/egyptian-artifacts/

Anthony, J. (2023, 10 October). Egyptian Artifacts – Treasures of the Nile. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/egyptian-artifacts/

Anthony, Jordan. “Egyptian Artifacts – Treasures of the Nile.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 10, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/egyptian-artifacts/.