Famous Marble Statues – Discover the 10 Best Examples

Artists have been sculpting marble statues since early antiquity, creating works that have stood the test of time and leaving viewers in awe of their elegance and magnitude. Below, we dive into what makes marble such a beautiful medium to create sculpture, and list 10 of the most famous marble statues in art history. So, if you’re ready, let’s jump in!

Contents

- 1 Why Is Marble Great for Sculpture?

- 2 A Brief History of Marble Sculpture

- 3 10 Famous Marble Statues

- 3.1 Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) by Unknown Artist

- 3.2 Elgin Marbles (c. 447 – 438 BCE) by Phidias

- 3.3 Venus de’ Medici (1st century BCE) by Cleomenes

- 3.4 Venus de Milo (150 – 125 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch

- 3.5 Augustus of Prima Porta (1st century CE) by Unknown Artist

- 3.6 The Townley Discobolus (2nd century CE) by Myron

- 3.7 La Pietà (1498 – 1499) by Michelangelo

- 3.8 David (1501 – 1504) by Michelangelo

- 3.9 Laocoön (1520 – 1525) by Baccio Bandinelli

- 3.10 The Veiled Virgin (c. 1850s) by Giovanni Strazza

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is Marble Great for Sculpture?

Marble has the upper hand in sculpture compared to other mediums like limestone, which is a more common material. For example, what makes it so suitable for representing human skin is that honed marble has the ability to absorb light, resulting in a soft visual effect. Marble is also extremely durable, with some sculptures (as we will see below) lasting thousands of years. Artists like marble because firstly, it is quite soft and easy to make marble carvings when the material is first extracted from the quarry. Secondly, marble becomes really dense and hard as it ages, promoting durability. Marble also comes in a variety of patterns and shades, although white marble is usually first prized because of its homogeneity and isotropy, and does not easily shatter. Additionally, white marble can look quite waxy, giving sculpture the appearance of human skin. This is due to its low refractive index of calcite refraction, which allows light to enter the material.

There are downsides to using marble like the fact that it is a rare stone, making it more expensive than many other types of stone used to create sculpture. Transportation of marble is also difficult because it can be extremely very heavy. In addition, marble can be more prone to cracking on extended structures and limbs of an artwork compared to bronze, because it has a lower tensile strength. Compared to granite, marble is not as weather-resistant, and tends to stain easily as it absorbs skin oils.

A Brief History of Marble Sculpture

Stone sculpture was mostly made using sandstone, limestone, gypsum, alabaster, clay, or jade before Classical Antiquity. Marble started being used on a more regular basis from the Greek Archaic period (c. 650-480 BCE) onwards. During the Greek Classical period (c. 480-323), we see the glorious Parthenon reliefs, and it is at this time that the use of bronze became just as prominent. Roman sculpture also prized the use of the marble, especially in Roman reliefs. Important factors in the use of marble for sculpture were its cost, and the proximity of quarries, such as those quarrying for marble stone like carrara, pentelic, and parian types.

These factors contributed to the reason why many churches, cathedrals, and abbeys were not decorated with marble during the Romanesque and Gothic periods.

However, sculptors during the Renaissance had more wealth, and therefore, artists like Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) used a lot of marble in his work. Another reason why artists during this period preferred marble to other types of stone is because of the resurgence in the interest in ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, which they associated strongly with marble. Marble remained a popular choice during the later Classicism and Baroque periods, and until the start of the 20th century, its superiority continued in European art academies.

10 Famous Marble Statues

There are many beautiful marble sculptures in the world, and we can unfortunately not list all of them. However, we have listed the 10 most famous marble statues below and their locations so that one day you can view these extraordinary pieces with your own eyes.

Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) by Unknown Artist

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Peplos Kore |

| Date Created | c. 530 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Height of 118 |

| Currently Housed | Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece |

This Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) sculpture was discovered in 1886 on the Acropolis of Athens near the temple Erechtheion, and is one of the most famous examples of Archaic Greek art. Kore sculptures represent young women, and in ancient Greek literally translates to ‘girl’ or ‘young woman’. The word peplos refers to the gown popularly worn by women in Archaic Greece, and when this work was found it was thought that she was wearing a peplos, but now we know that she is not wearing one.

During the 6th and 5th centuries, these sculptures were often used as dedicated offerings to gods, or as markers at gravesites.

Kore sculptures were typically made to have very stiff postures with the head facing forward. The Peplos Kore is not very typical as she is not entirely straight; her weight is transferred to one leg, and her face is leaning slightly to the side. The white marble statue would have been colorfully painted, the original pigment of which is confirmed in traces found on its surface.

Elgin Marbles (c. 447 – 438 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist | Phidias (5th century BCE) |

| Artwork Title | Elgin Marbles |

| Date Created | c. 447 – 438 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 7,498.08 |

| Currently Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The Elgin Marbles (c. 447-438 BCE) were taken to Britain from Greece during the Ottoman Empire by representatives of the 7th Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce (1766-1841), a nobleman who is mostly known for his controversial procurement of these sculptures. The collection of these Ancient Greek marble works was removed from the Parthenon as well as from other buildings in Athens. Most of the works have been dated to the 5th century BCE, their creation being under the direction of Phidias (c. 480-430 BCE), a Greek architect and sculptor.

The removal of these sculptures from their place of origin led to a storm that brought forth questions surrounding the ownership of cultural artifacts and their return.

The Parthenon Sculptures refers to the sculptures of the collection that are from the Parthenon and they consist of a frieze depicting marble carvings of the Panathenaic festival procession, pediments of the Parthenon showing various gods and legendary heroes, a number of sculpted relief panels or metopes depicting the Centaurs and Lapiths’ battle during the feast at the marriage of Peirithoos. 75cm of the original frieze, 17 pedimental figures, and 15 metopes are housed at the British Museum.

Venus de’ Medici (1st century BCE) by Cleomenes

| Artist | Cleomenes (1st century BCE) |

| Artwork Title | Venus de’ Medici |

| Date Created | 1st century BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Height of 153 |

| Currently Housed | Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

This Venus de’ Medici (1st century BCE) sculpture from the Hellenistic period was created by the Greek marble sculpture artist Cleomenes (1st century BCE). It depicts Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of beauty and love. The parian marble sculpture is a copy of the original one that was bronze. Parian marble is a pure-white flawless marble that has a fine grain and is partly translucent. It was quarried on the Greek island of Paros during the classical era and the ancient Greeks valued it extremely highly for producing sculpture.

The Venus de’ Medici has become one of the points of reference by which the development of the classical sculptural tradition of the West is drawn.

The process of classical scholarship and changes of taste is outlined by references made to the sculpture. The pose that the goddess is depicted in is a moment of vulnerability, as she stands surprised in an effort to cover her private areas with her hands as she emerges from the sea. There is a dolphin at her feet further suggesting her whereabouts, while at the same time it acts as a supportive structure. The bronze original would not have needed its support.

Venus de Milo (150 – 125 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch

| Artist | Alexandros of Antioch (2nd – 1st century BCE) |

| Artwork Title | Venus of Milo |

| Date Created | 150 – 125 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 204 |

| Currently Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

This marble depiction of Aphrodite is credited to have been created by the Greek sculptor, Alexandros of Antioch during the Hellenistic period. The Venus of Milo (150 – 125 BCE), alternatively called the Aphrodite of Milo, is very well preserved, considering that most sculpture from ancient Greece is either badly damaged or has not survived. However, this work is not wholly intact. The original plinth on which she stood is missing, as well as both of her arms, an earlobe, and a foot. She is depicted with a nude torso with the lower half of her body draped in fabric.

The sculpture was originally thought to have been produced by Praxiteles, an Athenian sculptor from the fourth-century BCE, but upon finding the inscription on the base of the work later on, it was attributed to Alexandros of Antioch.

The sculpture has an interesting connection to the historical cultural heritage of France, with the French authorities having implemented a major propaganda campaign in the 19th century. Venus of Milo was exported from Greece to France and placed in the Louvre, with Napoleon Bonapart watching over this expedition. It was during this period that the museum was hit with issues regarding the repatriation of various pieces, Venus of Milo being one of them. The French authorities were reluctant to release the work and led a campaign to keep her in France.

Augustus of Prima Porta (1st century CE) by Unknown Artist

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Augustus of Prima Porta |

| Date Created | 1st century CE |

| Medium | marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Height of 208 |

| Currently Housed | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

The famous Augustus of Prima Porta (1st century CE) is by an unknown artist from the Roman artistic tradition. The study of Roman sculpture can often be complicated by its connection to Greek art. Many Roman sculptures are noted as ‘copies’ of Greek originals and at one point, this aspect of imitation limited the Roman imaginative scope in the eyes of historians.

However, the art of the Roman tradition began to be re-evaluated in its own right by the end of the 20th century.

This sculpture depicts the first Roman Emperor, Caesar Augustus (63 BCE – 14 CE), also known as Octavian. Archaeologists found the statue in 1863 during excavations at the Villa of Livia, which was owned by Livia Drusilla, the wife of Augustus. The sculpture is believed to be based on a bronze original which used to be displayed in Rome but that is since lost. The work is seen as the best-known portrait of Augustus and is one of the most famous ancient sculptures.

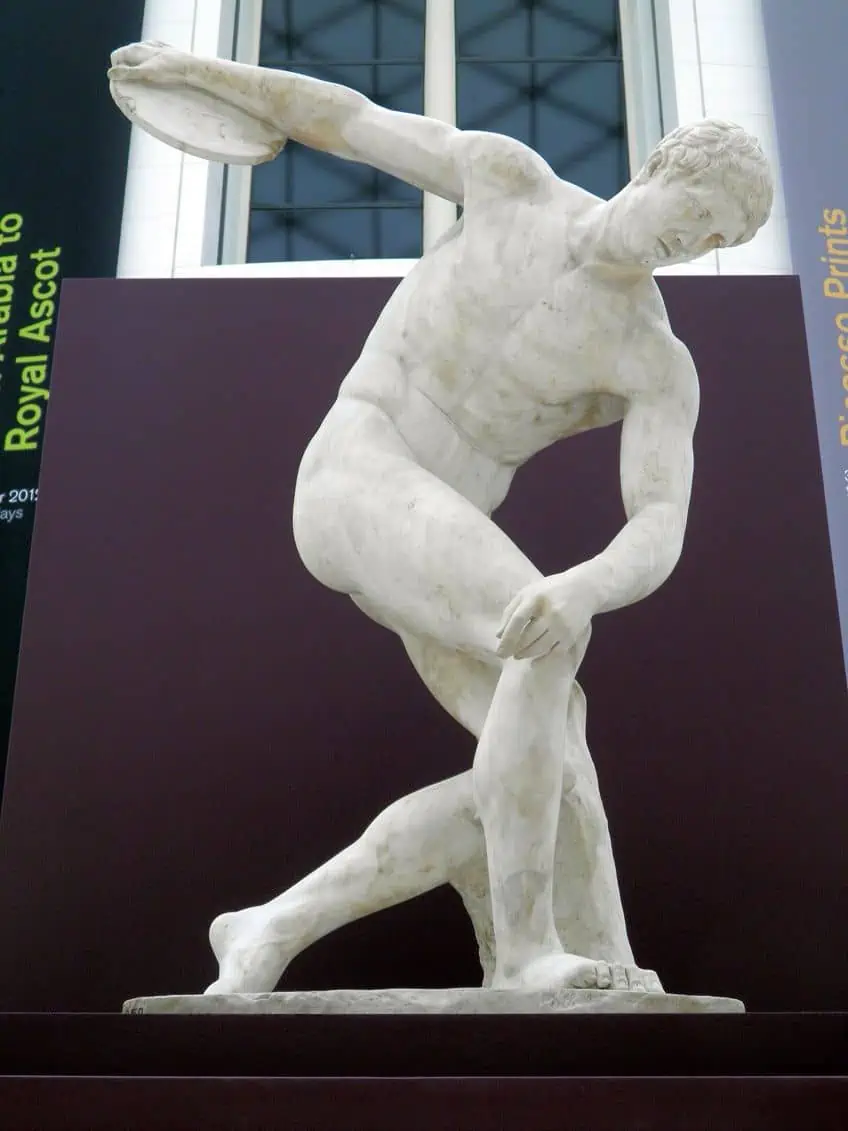

The Townley Discobolus (2nd century CE) by Myron

| Artist | Myron (c. 460 – 420 BCE) |

| Artwork Title | The Townley Discobolus |

| Date Created | 2nd century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 170 x 105 x 63 |

| Currently Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The Townley Discobolus (2nd century CE) depicts a discus-thrower, called a diskobolos or discobolus in ancient Greece leaning forward in a poised position about to throw a discus. This Graeco-Roman sculpture is a copy of the original bronze work created in the 5th century BCE by the Athenian sculptor, Myron (c. 460-420 BCE). The marble sculpture was excavated at Tivoli at Hadrian’s Villa in 1791 close to Rome, and was purchased the next year by Thomas Jenkins, a dealer in sculpture and antiquities.

The head of this particular copy of the Discobolus (as there was more than one) was not restored correctly, as the original one had his head facing in the opposite direction, looking back towards the discus.

Allegedly, the head was found near the excavated statue at Hadrian’s Villa. It was common practice for works of antiquity to be “restored” without evidence that the parts used even belonged to each other. A complete work of art was important to collectors and clients of ancient works. The parts of the sculpture that were restored were the nose, chin, lips, a part of the neck, as well as the right hand and the discus it held, some of the toes, a part of the right knee, and the left hand.

La Pietà (1498 – 1499) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Artwork Title | La Pietà |

| Date Created | 1498 – 1499 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 174 x 195 |

| Currently Housed | St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City |

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475 – 1564), best known as Michelangelo was an architect, sculptor, and painter from the High Renaissance and is considered one of the most important artists in history. Pietà (1498 – 1499) or formally titled, Madonna della Pietà depicts the mother of Jesus, Mary holding her son’s body after he has died on the cross. The work was made initially as a funeral monument for Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, the French ambassador of Rome.

Upon completion of the sculpture, however, it was thought that it was so beautiful that it was placed in Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City rather than to simply be used for funerals.

The sculpture is full of beautiful detail, with realistic precision in Mary’s clothes and robes, the hands of Jesus, and Mary’s face, which looks younger than that of Jesus. Michelangelo captures the heaviness of the dead body of Jesus as he lies across Mary’s lap. It is the only work of Michelangelo’s that the artist ever put his signature on.

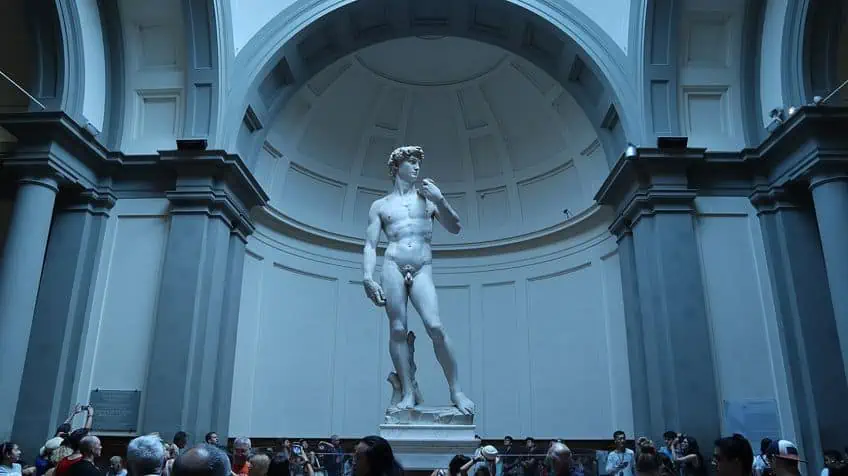

David (1501 – 1504) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Artwork Title | David |

| Date Created | 1501 – 1504 |

| Medium | Pentelic marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 517 x 199 |

| Currently Housed | Accademia Gallery of Florence, Florence, Italy |

The sculpture of David (1501-1504) in pentelic marble has to be one of the most memorable and magnificent sculptures in the world. Michelangelo’s representation of David is considered a masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture and measures an impressive 5.17 meters tall.

David is a figure featured in the Christian Bible for defeating a much larger Goliath with only a sling and a stone he collected from the riverbed.

David’s faith overcame his fear. Witnessing this, the Philistines fled and Saul was obliged to make David the head of his army. For the Republic of Florence, this sculpture therefore swiftly became a symbol for the defense of civil liberties, as it was an independent state threatened by rival states more powerful than them, and by the dominance of the Medici family.

Laocoön (1520 – 1525) by Baccio Bandinelli

| Artist | Baccio Bandinelli (1493 – 1560) |

| Artwork Title | Laocoön |

| Date Created | 1520 – 1525 |

| Medium | Luni marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Height of 213 |

| Currently Housed | The Uffizi, Florence, Italy |

The very famous sculpture, Laocoön (1520-1525) was produced by the Medici family’s favorite artist, Baccio Bandinelli (1493 – 1560). The impressive marble work is a copy based on the original bronze sculpture discovered in Rome in 1506. There was an uproar following its discovery. It had been historically praised by Pliny the Elder (c. 23 – 79 CE) in his writings, stating that the palace of Titus was believed to have been the initial place where the work was positioned.

Ancient sources attribute the original sculpture to a group of Greek sculptors, Hagesandros (1st century BCE), Athenedoros (1st century BCE), and Polydoros (c. 50 BCE – c. 0 BCE) of Rhodes who relocated to Italy in the 1st century BCE.

The marble sculpture depicts the attack of Laocoön, a Trojan priest, and Thymbraeus and Antiphates, his sons by serpents of the sea. The suffering conveyed in this work is unlike that of martyrs and the Passion of the Christ often shown in Christian art, as there is no reward or redemption offered by the agony experienced by Laocoön and his sons. The figures contorted facial expressions, as seen in Laocoön’s exaggeratedly bulging eyebrows, show this agony, but are physiologically impossible. In addition to their straining bodies, this dramatization further emphasizes the subjects’ torture.

The Veiled Virgin (c. 1850s) by Giovanni Strazza

| Artist | Giovanni Strazza (1818 – 1875) |

| Artwork Title | The Veiled Virgin |

| Date Created | c. 1850s |

| Medium | Carrara marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Height of 48 |

| Currently Housed | Presentation Convent, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada |

The Veiled Virgin (c. 1850s) was made in Rome by Giovanni Strazza (1818-1875), a leading Italian sculptor at the time. The carrara marble sculpture portrays the bust of the Virgin Mary with a veil covering her face. Her eyes are closed as her head leans forward as if quietly praying or mourning. Carrara marble is a high quality marble with a great tensile strength that makes it the perfect medium for producing veiled sculptures as it can hold fine detail.

Unfortunately, we do not know the exact date the work was created, but the 1850s is the probable time period.

There was a revival in nationalism during the middle of the 19th century in Italian music and the arts, and Italian nationalism as a whole. Part of the Italian Risorgimento, a movement that assisted in awakening the Italian peoples’ national consciousness, Strazza’s veiled female work became a favorite subject for fellow contemporaries. The image of the veiled woman was often used to personify or symbolize Italia, in the same way in which Lady Liberty did for the United States, Hibernia for Ireland, and Britannia embodied England.

Thank you for reading our article on famous marble statues and some of the most skilled marble sculpture artists in art history. We hope that you continue your inquisition into the world of sculpture, and perhaps explore other fascinating sculpture mediums as well!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Type of Marble Is the Most Famous?

The most famous type of marble is probably carrara marble, as it is known all over the world for being used to create some of the greatest sculptures in art, as well as important buildings and historical monuments. It is a high-quality marble with a great tensile strength that makes it perfect for producing works with fine detail.

Which Artist Is the Best Marble Sculptor?

Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) is perhaps one of the most well-known sculptors in art history for producing some of the most spectacular marble sculptures in Western art, such as David (1501 – 1504), La Pietà (1498 – 1499), and Moses (1513 – 1515), to name a few. The way in which he brought physical realism and complexity to his figures sets him apart from his contemporaries.

Jaycene-Fay Ravenscroft is a writer, poet, and creative based in South Africa, boasting over 6 years of experience working in a contemporary art gallery. She earned her Bachelor of Arts degree with majors in Art History and Ancient History from the University of South Africa, supplementing her studies with courses in Archaeology and Anthropology. Driven by a passion for learning, Jaycene-Fay finds inspiration in symbology and the interconnectedness of the world. Trained to analyze and critique art, she is enthusiastic about delving into the meanings behind each artwork, exploring its ties to the artist’s cultural, historical, and social context. Writing serves as Jaycene-Fay’s means of researching, sharing knowledge, and creatively expressing herself. For artfilemagazine, Jaycene-Fay writes articles on art history with a focus on historical paintings.

Learn more about Jaycene-Fay Ravenscroft and about us.

Cite this Article

Jaycene Fay, Ravenscroft, “Famous Marble Statues – Discover the 10 Best Examples.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 2, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/famous-marble-statues/

Ravenscroft, J. (2023, 2 November). Famous Marble Statues – Discover the 10 Best Examples. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/famous-marble-statues/

Ravenscroft, Jaycene Fay. “Famous Marble Statues – Discover the 10 Best Examples.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 2, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/famous-marble-statues/.