Fresco Painting – Introducing the Ancient Art Form

What is a fresco painting and are there different fresco techniques? Based on the fresco art definition, frescoes are a type of mural painting produced by applying pigment onto lime plaster that is freshly laid. Once the plaster dries, the fresco paintings become permanently integrated into the wall. This technique is called buon fresco, whereas painting on a dry surface is known as fresco secco.

What Is a Fresco Painting?

Fresco art dates back to antiquity and is often linked with the Italian Renaissance era. Fresco techniques were utilized to create many of the masterpieces we can still view today in public buildings, churches, and palaces. Let us now take a look at the various fresco techniques employed by fresco artists.

The Different Fresco Techniques

Fresco artists employed several different methods to produce their fresco paintings. The most common technique is known as “true” fresco, or buon fresco, which requires a freshly laid lime plaster surface. Fresco secco paintings are produced on dry plaster and required a binding medium to be added to the pigment in order for it to adhere to the surface.

The third technique used by fresco artists is called a mezzo fresco painting and is produced on semi-dried paster.

The Buon Fresco Technique

Color pigments are blended with water and applied to the intonaco (a thin layer of fresh, wet plaster). Due to the chemical properties of the plaster, no additional binder is necessary because the pigments combined purely with water sink into the intonaco, which becomes the medium retaining the color. After a few hours, the intonaco dries in reaction to air, and it is this chemical process that sets the pigments permanently in place. Before painting a buon fresco, a coarse underlayer known as the arriccio is applied across the entire surface to be painted and left to set for several days.

Numerous painters drew their compositions on this underlayer in sinopia, a reddish pigment. Subsequently, new methodologies for transferring paper designs to the surface arose. The major lines of a paper sketch were pierced with a needle, the paper was held against the surface, and a bag of soot was pounded on them to create black dots all along the outlines. If the fresco painting was being applied over an older fresco, the wall would be roughened to increase adhesion. The intonaco was applied to the area of the wall that was planned for completion that day, sometimes following the shapes of the people or the landscape, but usually simply beginning from the top of the piece.

In a large fresco, the distinct phases are frequently recognized by a slight seam that divides one day’s work from the next. Due to the quick drying plaster, buon frescoes are challenging to create. A layer of fresh plaster will typically take 10 to 12 hours to set; ideally, the fresco artists would start painting one hour after the plaster was laid and continue painting until two hours before it began to fully dry, providing the artist with seven to nine hours in which to work. After that area has dried, no more painting may be done, and the unpainted layer of plaster must be scraped away with a tool before beginning the following morning.

In large fresco artworks, 20 or more various sections can sometimes be seen, each section representing a single session of work.

The carbonation of the lime, which sets the color in the plaster and ensures the fresco’s longevity for future generations, is an essential element of this technique. In the iconic paintings of Raphael and Michelangelo, indentations were scraped into specific portions of the plaster while it was still wet to enhance the feeling of depth and to accentuate some areas over others. The learners of the School of Athens’ eyes are sunken in using this method, making them appear deeper and more realistic. This method was employed by Michelangelo as part of his signature ‘outlining’ of the figures in his fresco paintings.

The Fresco Secco Technique

Because fresco secco paintings are painted on dry plaster, the pigments necessitate a binding agent, such as tempera, oil, or glue, to adhere to the wall. It is vital to differentiate between a fresco secco artwork produced on top of a buon fresco painting, (which most sources agree was typical from the Middle Ages onward) and fully a fresco secco artwork produced on a blank wall. In general, buon fresco paintings outlast any secco painting done on top of them because secco works last longer with a roughened plaster surface, but buon frescoes should have a smooth surface.

The extra fresco secco work would be added to make modifications and occasionally to add minor features, but also because not all colors can be produced in true fresco since only certain pigments function chemically in the extremely alkaline lime-based plaster. Since neither lapis lazuli nor azurite blue, the only two blue pigments available at the time worked well in wet fresco, the sky, and blue garments were typically added as a fresco secco layer afterward. Sophisticated analytical techniques have also revealed that, even in the early Italian Renaissance, fresco artists regularly used a secco technique to enable the use of a greater range of colors.

Many early examples have since disappeared, but a complete picture painted in fresco secco over a surface roughened to provide a key for the paint could endure very well, though humidity is more dangerous to it than to buon fresco paintings.

The Mezzo Fresco Technique

A mezzo-fresco is produced on almost dried intonaco – firm enough not to leave a thumbprint – so that the color only slightly permeates the plaster. By the end of the 16th century, this had fully superseded buon fresco, and painters like Michelangelo and Gianbattista Tiepolo utilized it. Since the dried plaster can be re-wetted and manipulated, mezzo fresco enabled fresco artists to paint at a slower speed and make modifications to the image while it is still in process. Mezzo fresco, though, is not nearly as durable as buon fresco since the colors do not sink as deeply into the plaster. As a result, mezzo fresco is often employed for smaller-scale artworks such as panels or ornamental objects rather than large-scale frescoes.

The History of Fresco Art

The history of fresco painting may be traced back to antiquity with ancient frescoes discovered in the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, which were damaged by Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 CE. Yet, fresco art reached its highest point in Italy during the Renaissance period.

Let’s take a look at some of the most significant eras and regions in which fresco art flourished.

The Fresco Paintings of Ancient Near East and Egypt

The first Egyptian fresco ever found was discovered at Hierakonpolis and dated to around 3500 BCE. Some of the topics and designs displayed in the fresco are also seen in other Naqada II artifacts, such as the Gebel el-Arak Knife (3300 BCE). It depicts a man fighting two lions, Egyptian and foreign vessels, and fighting scenes. The Ancient Egyptians painted numerous tombs and homes, but these are not true frescoes.

The Fresco Art of Aegean Civilizations

The earliest buon frescoes originate from the Bronze Age and are found throughout Aegean civilizations, including Minoan artwork from the island of Crete and neighboring Aegean Sea islands. The Bull-Leaping Fresco (1450 BCE), the most renowned of these frescoes, portrays a religious event in which people jump over the backs of massive bulls.

The earliest surviving Minoan fresco paintings, dating from the Neo-Palatial era, can be seen on the island of Santorini.

While comparable fresco artworks have been discovered in other parts of the Mediterranean basin, notably in Morocco and Egypt, their origins remain a mystery. Several art historians suggest that fresco artists from Crete were dispatched to other regions as part of a commercial exchange, bringing to light the significance of this art form in the culture of the period.

The Fresco Paintings of Classical Antiquity

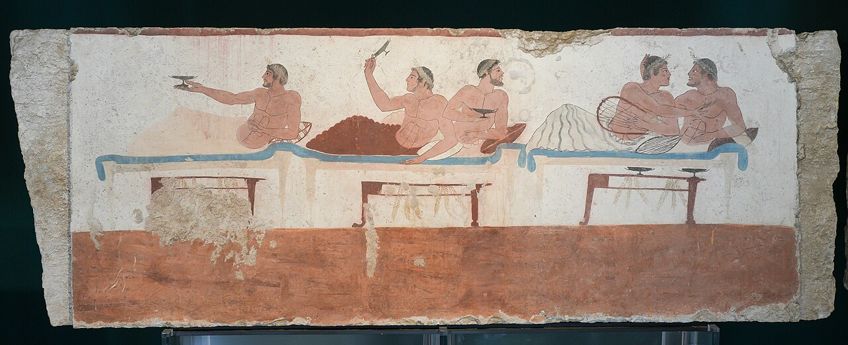

In ancient Greece, fresco artworks were also created, but few of these have remained. In June 1968, near Paestum, a Greek colony in southern Italy, a tomb featuring fresco paintings dating back to 470 BCE, known as the Tomb of the Diver, was found. These frescoes portray scenes from ancient Greek society and daily life and serve as significant historical documents. One depicts a bunch of men lounging at a symposium, and the other depicts a young man jumping into the ocean.

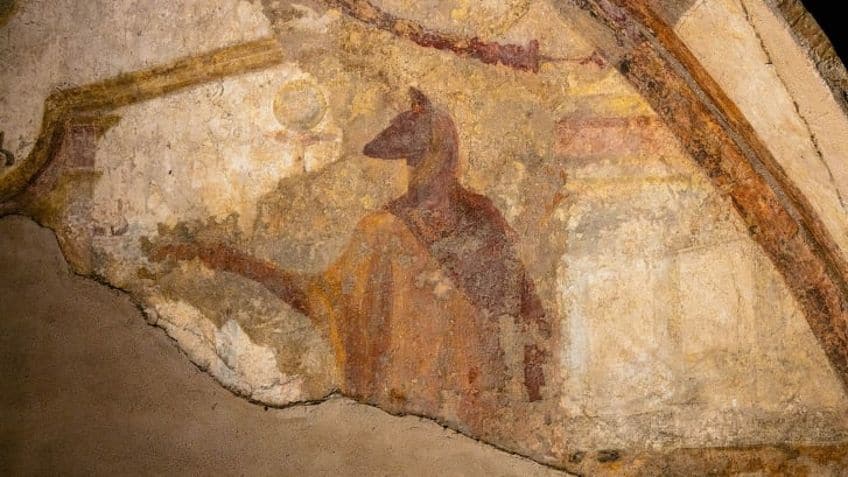

The Tomb of Orcus in Veii, Italy, has been found to contain Etruscan fresco paintings dating from the 4th century BCE.

The Tomb of Kazanlak’s lavishly painted Thracian frescoes date back to the 4th century BCE and was designated a World Historic Site by UNESCO. Roman wall murals, such as those at Pompeii’s famous Villa dei Misteri and Herculaneum, were painted in buon fresco. Christian frescoes from the first to second century CE were discovered in Rome’s catacombs, while Byzantine iconography was discovered in Crete, Cyprus, Cappadocia, Ephesus, and Antioch.

The Frescoes of India

Magnificent ancient and early medieval paintings have survived in more than 20 sites across India thanks to a huge number of old rock-cut cave temples. The paintings on the walls and ceilings of the Ajanta Caves were created between around 200 BCE and 600 CE and are India’s earliest known fresco artworks. These illustrate the Jataka tales, which are tales of the Buddha’s previous lives as a Bodhisattva. The narrative segments are shown one after the other, though not in chronological sequence. Since the site’s rediscovery in 1819, their attribution has been a central focus of study.

Ellora Caves, Armamalai Cave, Sittanavasal Badami Cave Temples, and other sites also contain valuable intact ancient and early medieval frescoes.

The earliest Chola pieces were unearthed in 1931 within the circumambulatory route of the Brihadisvara Temple in India. The methodology utilized in these frescoes has been identified by researchers. A smooth layer of limestone mixture was placed over the stones and allowed to be set for a period of two to three days. These big artworks were created in such a short period of time using natural organic paints.

The Chola frescoes were painted over during the Nayak period. The intense spirit of Saivism is represented in the Chola frescoes underneath. These most likely coincided with Rajaraja Cholan the Great’s building of the temple. The Pahari-style paintings may be found in their original form in Ramnagar’s Sheesh Mahal. These frescoes include scenes from the Ramayan and Mahabharat epics, as well as portraits of local rulers. Frescoes were utilized for interior decoration on walls and within dome ceilings during the Mughal era.

The Fresco Art of Sri Lanka

The Sigiriya Fresco paintings are located at Sigiriya, Sri Lanka, and were produced during King Kashyapa I’s reign. The widely held view is that they portray women from the king’s royal court as heavenly nymphs raining flowers on the humans beneath. These are similar to the Gupta style of art seen in India’s Ajanta Caves.

They are, though, significantly more lively and vivid in nature, and they are the only extant secular artworks from antiquity existing in Sri Lanka today.

“Fresco lustro” is the painting method utilized on the Sigiriya frescoes. It differs from the pure fresco approach in that it includes a little binding agent or adhesive. This increases the painting’s longevity, as seen by the fact that it has endured in the weather for nearly 1,500 years. Just 19 of these works remain now, located in a small protected depression 100 meters above ground. Yet, ancient sources indicate the existence of up to 500 of these fresco artworks.

The Fresco Paintings of the Middle Ages

The late Medieval and Renaissance periods witnessed the most significant utilization of frescoes, especially in Italy, where many government buildings and churches still have fresco decoration. This shift corresponded with a reconsideration of frescoes in the liturgy.

Romanesque churches in Catalonia were elaborately decorated in the 12th and 13th centuries, with both ornamental and educational roles (for the followers who were illiterate).

Church frescoes were popular in Denmark throughout the Middle Ages, and can be found in around 600 Danish churches as well as churches in southern Sweden. One of the few specimens of Islamic frescoes may be found at Qasr Amra, the Umayyads desert palace in the eighth century.

The Frescoes of Early Modern Europe

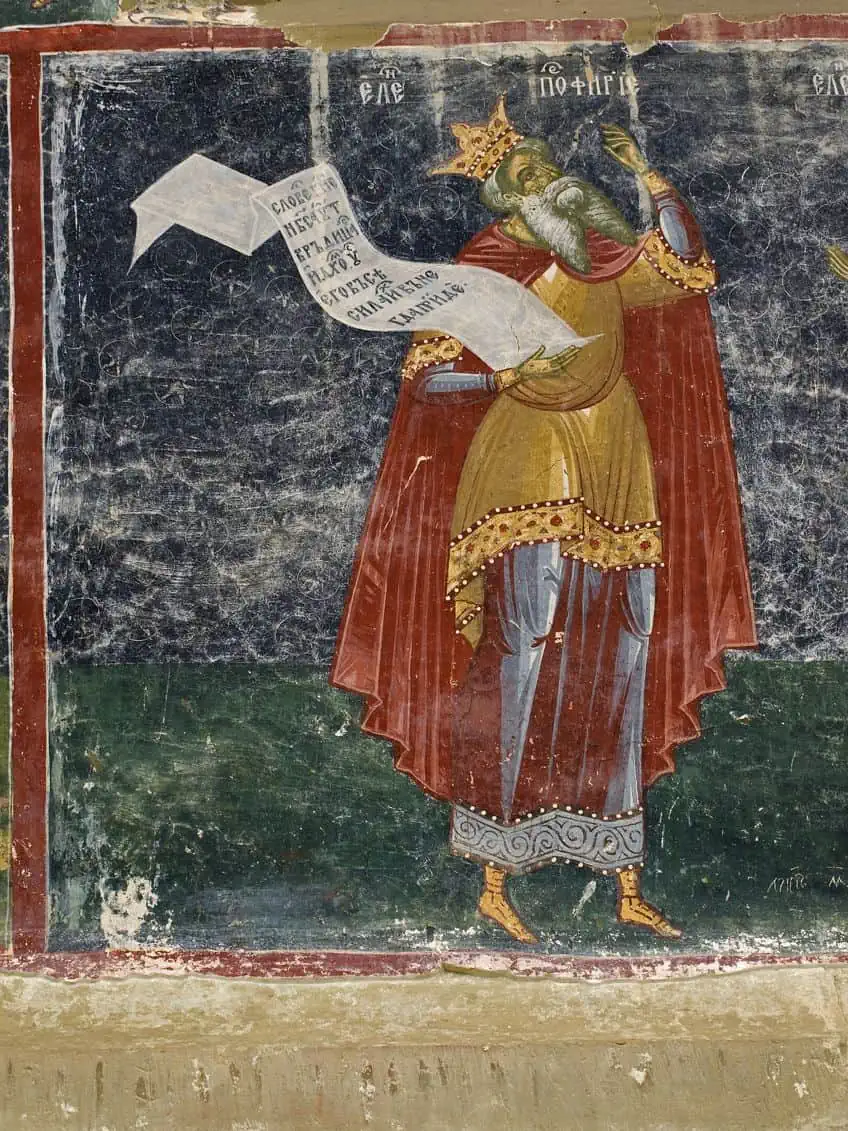

Northern Romania has around a dozen decorated monasteries dating from the last years of the 15th century to the early 16th century, with fresco paintings on the inside and outside. Suceviţa, circa 1600, is a late revival of the style established some 70 years before.

The practice of painting churches persisted in other regions of Romania throughout the 19th century, though not to the same degree.

Andrea Palladio, a renowned 16th-century Italian architect, constructed several homes with basic exteriors and magnificent interiors filled with fresco artworks. Henri Clément Serveau created numerous frescoes, including one at the Lycée de Meaux, where he had previously studied.

The Fresco Art of the Modern Era

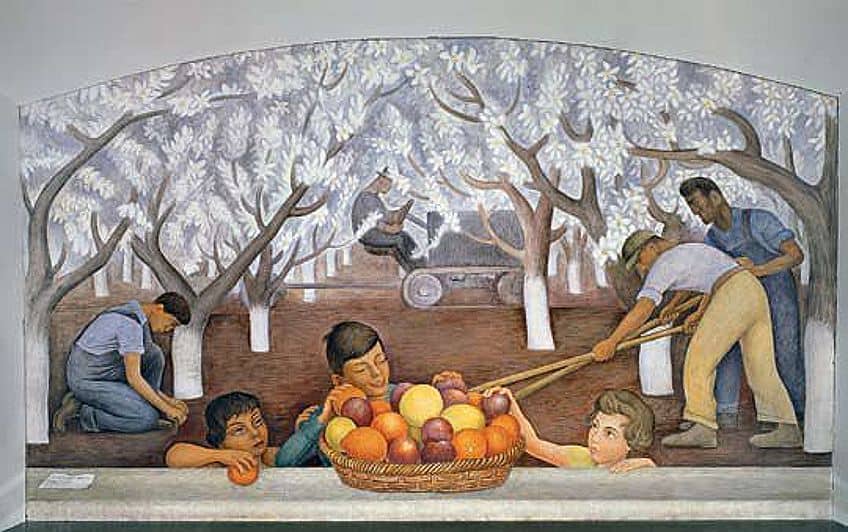

Throughout the 20th century, Mexican artists such as Fernando Leal, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Siqueiros revitalized the discipline of fresco art. Mexican Muralism was founded by channeling pre-Columbian Mexico artworks such as the paintings seen at Orozco, Teotihuacan, Siqueiros, River, and Fernando Leal. There have been far fewer frescoes made since the 1960s, however, there are several notable exceptions. Brice Marden, an American artist, said he was influenced by frescoes and watching craftsmen plaster stucco walls when he first showed his monochrome paintings at Bykert Gallery in New York in 1966.

As Marden was experimenting with the imagistic qualities of fresco, David Novros was building a 50-year career around fresco techniques.

Novros is a geometric abstraction artist from the United States. Donald Judd commissioned Novros to produce a piece at 101 Spring Street in New York, shortly after buying it in 1968. Novros created the fresco using medieval techniques, beginning with a full-scale sketch that he transmitted to wet plaster using the traditional pounding process, transferring powdered color onto the plaster through small holes in the sketch.

In 1985, James Hyde, another American artist, debuted his frescoes at the Esther Rand Gallery in New York. He was utilizing the authentic fresco technique on tiny panels of cast concrete set on the wall at the time. He experimented with several hard supports for the fresco plaster over the following decade, such as plate glass and composite board. Hyde presented a true fresco on a giant block of Styrofoam at the John Good Gallery in New York City in 1991.

While Hyde’s work includes everything from paints on photographic prints to abstract furniture design, large-scale installations, and photography, his fresco paintings on Styrofoam have been a staple of his since the 1980s. His frescoes were exhibited across the United States and Europe. Over its long and rich history, fresco artists have always used a methodical approach, whereas Hyde’s paintings are painted spontaneously. The Styrofoam structure’s modern disposability contrasts with the permanence of the antique fresco method. Hyde installed four car-sized fresco artworks on Styrofoam hung from a brick wall in 1993.

The Conservation of Fresco Paintings

For centuries, Venice’s temperature and environment have posed a challenge to the city’s Fresco paintings and other artworks. In northern Italy, the city is constructed on a lagoon. Rising dampness is a phenomenon caused by moisture caused by humidity and rising water levels over time. As the lagoon water level rises and permeates into a building’s foundation, it is absorbed and begins to rise through the walls, causing damage to these wall paintings. Venetians have proven pretty good at fresco conservation measures. After floods, the mold Aspergillus Versicolor can thrive and take nutrients from fresco artworks.

The technique outlined below was employed to save paintings in the Venetian opera house, La Fenice.

A polyvinyl alcohol and cotton gauze bandage is first applied. Soft brushes and targeted vacuuming are then used to remove difficult areas. Some parts that are simpler to remove (due to less water damage) are cleaned with a paper pulp compress soaked with deionized water and bicarbonate of ammonia solutions. These parts were reinforced and reattached, then cleaned with resin compresses and barium hydrate was used to reinforce the wall and pictorial layer.

Even if they are in minimal danger, fresco paintings that have been taken from their initial setting and transferred to cultural institutions benefit from being in a reasonably stable environment that is routinely examined. Nevertheless, fresco artworks that are still in their original location, such as places of cultural significance, are in significant danger since they are subject to environmental variables such as increased tourist traffic and other contaminants. As a result, data loggers are valuable for monitoring ambient conditions such as relative humidity and temperature, in addition to thermo-hygrometric sensors for micro-climate tracking for fresco artworks in outdoor, indoor, or semi-confined settings.

Notable Fresco Paintings

Throughout the centuries, many notable fresco artists have been commissioned to adorn the churches and public buildings by the clergy and state. These artists were typically very adept at producing fresco artworks as it was usually quite expensive and time-consuming to produce frescoes, so only the best were hired. While there are many famous frescoes around the world, there are a few that stand out as particularly notable.

These have been preserved for future generations to enjoy and many can be visited and seen in person. Here are a few of the most notable fresco paintings.

The Triumph of Death (1350) by Francesco Traini

| Artist | Francesco Traini (1321 – 1365) |

| Date of Completion | 1350 |

| Medium | Fresco painting |

| Dimensions (cm) | 313 x 556 |

| Location | Camposanto Monumentale, Pisa, Italy |

The Triumph of Death is commonly considered to be one of the most dramatic and terrifying pieces of medieval art, and has been seen as a statement on the fragility of human existence and the inevitably of death. Despite its grim subject matter, this fresco is widely regarded as a masterwork of Gothic art and a monument to Traini’s artistic skill and ingenuity.

The painting shows Death as a strong and scary figure riding on horseback and followed by an army of skeletal troops. The army is seen attacking a range of individuals, from peasants to monarchs, and from young to old. A group of characters is portrayed sitting at a table in the foreground of the artwork, seemingly ignorant of the turmoil and devastation going on around them.

The fresco is renowned for its detailed features and dramatic representation of warfare and death.

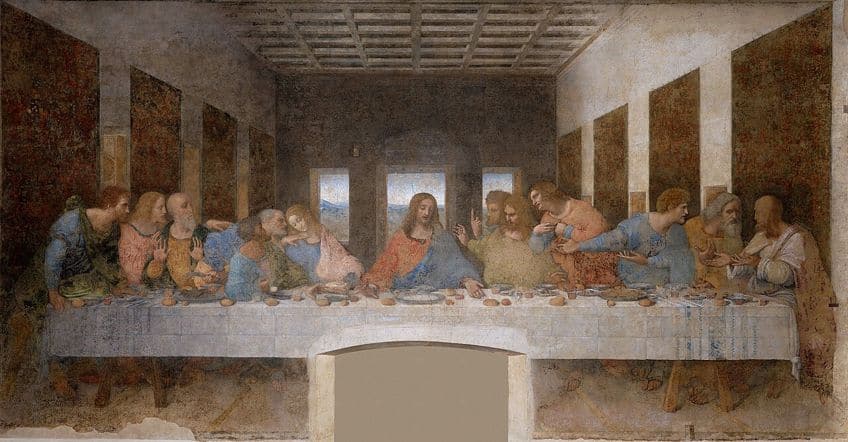

The Last Supper (1498) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) |

| Date of Completion | 1498 |

| Medium | Paint and plaster fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 460 x 880 |

| Location | Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy |

Leonardo da Vinci’s renowned fresco painting was created on the wall of the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The painting portrays Jesus telling his followers that one of them would betray him.

Each of the 12 disciples responds differently to the news, demonstrating the artist’s mastery of facial expression and body language. Unfortunately, the artwork has experienced deterioration over the years as a result of elements such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, and botched restoration attempts. The artwork is now meticulously conserved and safeguarded, and visitors may see it in the covenant’s refectory.

The fresco is particularly renowned for its incorporation of linear perspective, a technique pioneered by Da Vinci that provides the appearance of distance and depth in a two-dimensional artwork.

The School of Athens (1511) by Raphael

| Artist | Raphael (1483 – 1520) |

| Date of Completion | 1511 |

| Medium | Fresco painting |

| Dimensions (cm) | 500 x 770 |

| Location | Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, Italy |

This famous fresco is usually interpreted as a tribute to ancient Greek philosophy and culture, as well as a symbol of Renaissance humanistic values. The fresco is especially notable for its depiction of contemporaneous Renaissance characters, including Raphael and his colleague and competitor, Michelangelo, who is portrayed as one of the individuals in the painting’s background. The painting portrays a gathering of great ancient Greek philosophers and intellectuals in a large hall.

The fresco’s principal subjects are Aristotle and Plato, who are seen conversing in the center of the composition.

Several great Greek philosophers, such as Pythagoras, Socrates, and Euclid, are featured in the artwork, as are numerous other characters representing other branches of knowledge. The application of perspective in this famous fresco provides a feeling of space and depth inside the two-dimensional artwork. The figures are organized in such a way that the viewer’s attention is drawn around the picture, and the use of shadows and light enhances the appearance of three-dimensional space.

The Creation of Adam (1512) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Date of Completion | 1512 |

| Medium | Fresco painting |

| Dimensions (cm) | 280 x 570 |

| Location | Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, Italy |

The Creation of Adam is one of the numerous murals painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo, and it is usually considered to be one of his finest masterpieces. Throughout the years, the painting has been the subject of considerable interpretation and study and has been viewed as a representation of God’s strength and humanity’s potential.

The way Michelangelo portrays the human form is one of the artwork’s most stunning qualities.

Both God and Adam’s strong physiques are represented in exquisite detail, and the individuals are grouped in a dynamic and dramatic composition. The application of color, light, and shadow to create the sense of three-dimensional space is also noticeable in the fresco. The Sistine Chapel is now one of Rome’s most prominent tourist sites, with tourists from all over the world flocking to gaze at the grandeur and intricacy of Michelangelo’s frescoes.

Assumption of the Virgin (1518) by Titian

| Artist | Titian (1488 – 1576) |

| Date of Completion | 1518 |

| Medium | Fresco painting |

| Dimensions (cm) | 690 x 360 |

| Location | Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice, Italy |

This famous fresco portrays the Assumption when the Virgin Mary ascends to heaven. Mary is shown ascending towards a radiant light, surrounded by a multitude of cherubs and angels. A group of apostles below her stares up in awe as she fades from view. The artwork is renowned for its dynamic and fluid composition as well as its utilization of light, shadow, and color to create a feeling of motion and depth. This fresco is regarded as a High Renaissance masterwork, notable for its mix of technical excellence and spiritual depth. It is also among the most well-known pieces of art in Venice and draws tourists from all over the world, who come to be captivated by its beauty.

With that, we conclude our exploration of fresco painting. As we have seen, frescoes have been produced since ancient times and are still created right up to the present day. However, the various fresco techniques reached their peak in the Italian Renaissance period. Due to preservation efforts, many of the most notable fresco paintings still survive today. This means that these works of the Masters can still be appreciated for many more years to come.

Take a look at our fresco paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is a Fresco?

Frescoes are wall paintings that are created on walls and ceilings of buildings and churches. Many famous artists were commissioned to paint using this technique, as large pieces could be produced and the technique would ensure the longevity of the artwork. This has proven to be an efficient method, evidenced by all the remaining fresco paintings that still exist today.

What Is the Fresco Art Definition?

Frescoes are often defined as murals, however, not all murals are produced using fresco techniques. Buon fresco refers to artworks that were produced on fresh lime plaster using various pigments mixed with water. Fresco secco is a technique where the painting is produced on a dry surface, sometimes as the second layer on top of a buon fresco layer. There is also a thirst technique, referred to as the mezzo fresco technique. This fresco painting technique consists of adding pigments to a semi-dry wall surface.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Fresco Painting – Introducing the Ancient Art Form.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 23, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/fresco-painting/

Anthony, J. (2023, 23 October). Fresco Painting – Introducing the Ancient Art Form. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/fresco-painting/

Anthony, Jordan. “Fresco Painting – Introducing the Ancient Art Form.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 23, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/fresco-painting/.