Functional Art – When Artists Make Utility Their Concept

What is functional art or utilitarian art? Before we can understand the functional art definition, we first need to answer another question: “What is functionality?”. Functional objects serve a practical purpose, whereas fine art usually only serves to be aesthetically pleasing. However, functional art examples, such as functional sculptures, bring the practical and aesthetic together.

Contents

- 1 What Is Functional Art?

- 2 Functional Art Examples

- 2.1 Egyptienne Lamp (1933) by Alberto Giacometti

- 2.2 The Mayersdorff Bar (1966) by François-Xavier Lalanne

- 2.3 Mae West Lips Sofa (1972) by Salvador Dalí

- 2.4 Brushstroke Chair and Ottoman (1988) by Roy Lichtenstein

- 2.5 Lockheed Lounge (1990) by Marc Newson

- 2.6 Boomerang (2006) by Ai Weiwei

- 2.7 Real Time Series (2009 – Present) by Maarten Baas

- 2.8 Art Notes: The Almighty Dollar (2017) by Era and Donald Farnsworth

- 2.9 Spotley Cru (2017) by the Haas Brothers

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Functional Art?

According to the functional art definition, functional or utilitarian art refers to appealing things that fulfill practical needs, filling the precarious gap between the fine arts and the commonplace. The category is incredibly broad; it includes everything from furniture to lights, dinnerware, and even books. Functional art incorporates these aesthetic standards into functional objects that you may not have expected to perceive as art, whereas the word “fine art” often refers to pieces that convey an emotional and intellectual sensitivity combined with a touch of traditional beauty.

Although there were movements that had taken everyday objects and transformed them into art through the acts of selection and assemblage, such as Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, these did not have any functional value. However, like Man Ray, Duchamp did design at least two chess sets that can be considered prime examples of functional art.

Functional art refers to well-constructed artistic compositions that may serve practical functions but that collectors might prefer to display on a shelf. Many utilitarian art items are now collected with the same zeal as fine art pieces and are valued for their aesthetics as well as their functionality. Ancient Chinese vases, for instance, are valued more for their cultural and artistic worth than for their ability to serve their intended purpose of holding and displaying flowers.

The Bauhaus Influence

The famed Bauhaus school, established in 1919 by Walter Gropius, the renowned German architect, was conceived as a groundbreaking academic institution that would eliminate the barriers separating design and fine art. Famous artists such as Anni Albers, Josef Albers, Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee instructed students in an unconventional program and urged them to unify craft and art with a broad range of specialized courses.

Though the academy eventually closed in 1933 due to increasing financial difficulties and Nazi state pressure – resulting in several of its big names moving to teach in the United States – its unorthodox style and approach to craftsmanship and education have proven highly impactful even to the present day, with the Bauhaus influence visible in architecture, modern art, and design.

Design in the Modern World

The Museum of Modern Art in New York was among the first to realize the significance of utilitarian art, establishing its Architecture and Design section in 1932. From utilities and dinnerware to sports vehicles and even a helicopter, the design collection comprises a profusion of brilliantly designed functional objects from significant trends over the last 80 years. The museum has assembled a devoted design shop across the street where tourists can take back home contemporary functional art examples, as well as hosting a succession of renowned art shows on the topic, such as the acclaimed 2011 exhibition Talk to Me, which investigated how humans communicate with evolving technology.

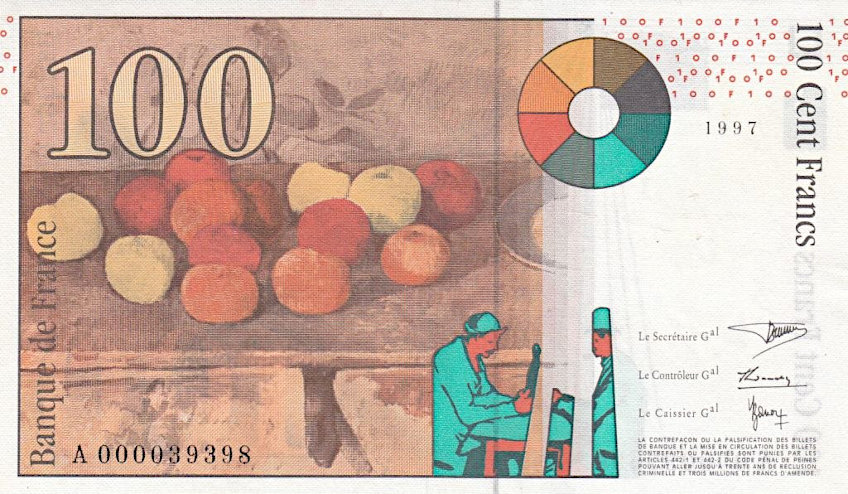

Art in Currency

Currency has historically acted as a beautified useful item, despite the fact that its intrinsic beauty is sometimes obscured by its crucial functional role. Coinage, and subsequently, paper bills, the graphic aesthetic of which has become increasingly complicated in order to deter forgers, have been imprinted with characteristics of both the currency’s worth and civilization of origin from its conception as a unit of economic exchange. For example, In the late 1990s, an image of Paul Cézanne was depicted on the 100 franc note used in France, with a replica of one of his works on the back.

Currency’s association with problematic financial systems has made it a natural target for painters such as Donald and Era Farnsworth, Cildo Meireles, Andy Warhol, and Rirkrit Tiravanija.

The Formation of A-Z

A couple of years after she graduated with an MFA in sculpture, Andrea Zittel launched A-Z Administrative Services in 1992, a company in which she developed multi-use household items like aprons and bowls. She gradually progressed to making even more personalized products, such as compact, portable “Living Units” dedicated to a particular aspect of living, such as dining or amusement. Zittel pushed a paradigm of self-sufficiency for creators and customers by designing things that helped satisfy the fundamental necessities of home, furniture, and clothes, putting her work solidly inside the country’s corporatized society.

The Impact of Fashion

Fashion represents one of the haziest distinctions between utility and fine art. Haute couture clothes, while highly styled to an extreme degree, are still, at their core, intended to be worn. Collaborative efforts between fashion designers and notable artists have been regular in the past few decades, with Takashi Murakami’s borrowing and subsequent reinvention of Louis Vuitton designs being a classic example. The overlap between utilitarian art and fine art has become less controversial as fine-art establishments like the Metropolitan Museum of Art join the trend and dedicate significant shows to renowned fashion designers and era styles.

Functional Art Examples

While we usually consider great art as something to look at rather than touch, numerous prominent creators have produced incredible pieces of utilitarian art over their careers. The subsequent pieces have adorned the residences of celebrities, become notable works of admiration, and have occasionally been inspired by an urge to bring their 2D works into a 3D format, while others have simply appreciated the tactility and functionality of creating functional artworks. Here are a few examples of famous functional art pieces.

Egyptienne Lamp (1933) by Alberto Giacometti

| Artist | Alberto Giacometti (1901 – 1966) |

| Date Completed | 1933 |

| Medium | Painted plaster |

| Dimensions (cm) | 49 x 46 |

| Current Location | Sothebys, London, United Kingdom |

Alberto Giacometti’s lamp, built around 1934 for Jean-Michel Frank, pays stylistic tribute to the extremely intricate and creative oil lamps unearthed in the tombs of Egyptian king Tutankhamun in 1922. “The most magnificent artwork for me is neither Roman nor Greek and definitely not Renaissance either, it is Egyptian”, the youth wrote in 1920 to his parents from Rome. “The Egyptian statues are exceptional in their perfection, evenness of form and design, and a faultless workmanship that has never been surpassed”.

Giacometti was particularly interested in the separation between sculpture and object in his own works, therefore it is inevitable that the artist was intrigued and inspired by the majestic proportions and lines of the Egyptian oil lamps.

His interpretation of the shape stripped it down to its most basic, fundamental pieces, removing the oil lamp’s side armatures and carved floral patterns. As a consequence, the piece is deeply contemporary and abstract, as well as an early witness to the artist’s lifelong obsession with Egyptian and African artworks, which had a huge effect on his creative approach throughout his career.

The Mayersdorff Bar (1966) by François-Xavier Lalanne

| Artist | François-Xavier Lalanne (1927 – 2008) |

| Date Completed | 1966 |

| Medium | Maillechort, steel, brass, copper, and blown glass |

| Dimensions (cm) | 209 x 157 x 223 |

| Current Location | Christie’s, London, United Kingdom |

The year 1966 was a watershed moment for François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne, highlighted by a string of brilliantly creative shows that quickly introduced the artists to an adoring worldwide press. After meeting Claude in 1952, François-Xavier decided to give up painting. The two painters moved into a modest studio on the Impasse Ronsin, which is today known as a renowned artist colony. The Lalanne’s relocated to the Impasse Robiquet in 1957. François-Xavier created his first sculptural piece here, utilizing welding equipment purchased in collaboration with Jean Tinguely. François-Xavier designed and built the current bar for private collectors, the Mayersdorffs of Brussels at this crucial moment.

The Mayersdorff bar, like the precedent he established the year before in 1965, was the result of secretive private commissions from sophisticated, pioneering clientele and was seldom, if ever, made public.

Each of these bars is one-of-a-kind. Each bar employs metal counterpoints counterbalanced by blown glass, and can be understood as two variations on the same theme—the portable, constrained 1965 example employs straight planes and lines, while the larger 1966 Mayersdorff bar possesses a more adaptable, portable character augmented by a sequence of graceful circles, curves, and spheres.

Mae West Lips Sofa (1972) by Salvador Dalí

| Artist | Salvador Dalí (1904 – 1989) |

| Date Completed | 1972 |

| Medium | Polyurethane foam couch |

| Dimensions (cm) | 110 x 183 x 81 |

| Current Location | Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom |

Salvador Dalí, possibly the most well-known Surrealist, encountered a kindred spirit in Edward James, the British poet, and collector in 1935. James was Britain’s most prominent surrealist admirer, and the two became close acquaintances, with James becoming a buyer of Dalí’s art. Dalí visited James at his London house in 1936, where they created many concepts for Surrealist items and furnishings.

It was James who recommended they make a sofa modeled on Dalí’s painting, Mae West’s Face which May be Used as a Surrealist Apartment (1935), which reimagines the crimson mouth of Mae West, the famous Hollywood sex symbol as furniture for a fantasy lounge space.

Two years later, the pair created the bizarre couch design for James’ family home. James had begun refurbishing it in an effort to construct a “full Surrealist house”. The renovation united James’ tastes in Victorian, Edwardian, and Surrealist styles, and it was the only house of its sort in the United Kingdom. Edward James had a pair of brilliant red Mae West Lips couches custom-made for the dining room. He commissioned and oversaw the fabrication of five distinct prototypes of the couch in various materials.

Brushstroke Chair and Ottoman (1988) by Roy Lichtenstein

| Artist | Roy Lichtenstein (1923 – 1997) |

| Date Completed | 1988 |

| Medium | Laminated Birch plywood |

| Dimensions (cm) | 179 x 45 x 69 |

| Current Location | National Gallery of Art, London, United Kingdom |

Although Lichtenstein’s pioneering Brushstroke canvases were made between 1965 and 1966, he continued to experiment with the motif in prints and drawings until 1971. He then opted to incorporate the artwork into another project. This functional artwork is the sole instance of Lichtenstein’s famous iconography being translated into the domain of functional design.

To actualize his idea, Lichtenstein chose the master artisans of the Graphic studio at the University of South Florida. Lichtenstein created complex drawings to explain the subtle nuances of form and design.

The statement, like Lichtenstein’s artwork, communicates simplicity through technical expertise. Using cutting-edge technology, 27 different layers of stiff white birch were turned into a practical chair from the artist’s dynamic emblem. The wavy borders reflect the quick motion of the brushstroke and the illusion of a trail of surplus paint caused by the swift motion. The use of a strong blue color recalls the artist’s previous painted topics. The ottoman, which is not present in all instances in the edition, accentuates the form’s dynamism even more.

Lockheed Lounge (1990) by Marc Newson

| Artist | Marc Newson (1963 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1990 |

| Medium | Polyester resin core reinforced with fiberglass, blind-riveted sheet aluminum, and rubber-coated polyester resin |

| Dimensions (cm) | 87 x 168 x 61 |

| Current Location | The Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia |

The Lockheed Lounge, named after the American aircraft manufacturer’s Machine-Age style, was infused with a series of subtle yet extremely personal inspirations. Newson had benefited from a cosmopolitan-style education as a youngster growing up in Australia, which included constant exposure to art galleries, museums, and, of course, movies. Most unique was Newson’s choice to design his seat as a chaise-longue, a rather obsolete shape by the late 20th century, and a choice that was largely inspired by Jacques-Louis David’s Portrait of Madame Récamier (1800).

The narrow wooden settee in this iconic picture helps only to raise the figure to immobility and eternity, echoing Antonio Canova’s memorial statues. Newson’s design, on the other hand, embraced mobility and movement, as well as the ebb and flow of the ocean’s tides, recalling his experiences as a surfer on the northern beaches of Sydney.

With the distant echo of classicism infused in the form’s idea, Newson sought to ensure the design’s modernity and to evoke a sense of shimmering transience by covering the whole surface with a continuous cloak of polished aluminum.

Boomerang (2006) by Ai Weiwei

| Artist | Ai Weiwei (1957 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 2006 |

| Medium | Glass lusters, plated steel, electric cables, and incandescent lamps |

| Dimensions (cm) | 700 x 860 x 290 |

| Current Location | Queensland Art Gallery, South Brisbane, Australia |

Boomerang is a towering example of globally acclaimed Chinese-born artist Ai Weiwei’s humorous approach to creating across cultural contexts. This large, brilliantly lighted waterfall-style chandelier, shaped like the renowned Aboriginal throwing weapon, hovers above the water as if it were in a hotel’s grand entrance. Ai Weiwei is known for incorporating common objects into art gallery settings. He has long recognized the impact of early-20th-century artist Marcel Duchamp, who legendarily took ordinarily commonplace things – like a men’s urinal and an overturned bicycle wheel – into a gallery and called them artworks, therefore inventing the “ready-mades”.

Duchamp’s protests against tradition opened up fresh avenues for art, demonstrating how an object’s meaning and significance may transform when it is placed in a different setting. As a result, Boomerang enlarges the chandelier, with its implications of riches, to ridiculous proportions, transforming it into the theme of an item linked with exotic concepts of Australia.

Real Time Series (2009 – Present) by Maarten Baas

| Artist | Maarten Baas (1978 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 2009 – Present |

| Medium | Various |

| Dimensions (cm) | Varying sizes |

| Current Location | Victoria Museum, Melbourne, Australia |

Maarten Baas’ functional sculpture, is one in a series of performances focusing on clunky and strange timekeeping systems, follows two people as they chart each passing second with mounds of rubbish. The footage is taken from above and follows the couple as they push rubbish lines representing the minute and hour hands across a vast circle dimly outlined in the countryside, keeping time as they go.

The video piece, which was released in 2009, is similar to previous brilliant pieces in Baas’ Real Time series, such as a painter painstakingly uncovering a computer display and another that shows the Dutch artist locked within a grandfather clock.

Guests at Amsterdam Airport’s international terminal in 2016 were also met with the Schiphol Clock, an analog gadget hung from the roof in which a man altered the time by hand, repainting every clock hand as the time ticked on. “The worker’s blue trousers, yellow rags, and red pail are inspired by the iconic Dutch artist Piet Mondrian”, Baas remarked.

Art Notes: The Almighty Dollar (2017) by Era and Donald Farnsworth

| Artist | Donald Farnsworth (1952 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 2017 |

| Medium | Acrylic inkjet on banknote |

| Dimensions (cm) | 6 x 15 |

| Current Location | Multiple prints available from Arstpace.com |

The artists’ parodied, contemplated, and reflected on politics, art, the monetary system, and the relationships between companies and the economy by using genuine dollar notes as the physical base for each work. Look attentively because there are several details, visual gags, and comments from artists and other progressive thinkers. Clearly, the Farnsworths are on a mission and enjoying this extended series. Working with a one-dollar note has presented an intriguing set of obstacles. The original banknotes’ elements were sanded, scraped with a razor blade, and even chemically erased.

The artists had to paint a background that was opaque enough to conceal the black lines of the previous engraving and also accept a layer of intricately designed inkjet printing in order to incorporate additional graphic elements into the design. This process took place over the course of nearly a year.

They eventually came up with a mixture of gum, titanium dioxide, and digital medium, which helps to bond and draw out the colors in the ink. They printed acrylic ink in the target sections of the bills with a coating of silver and gold leaf, then attached the leaf by hand straight to the wet acrylic.

Spotley Cru (2017) by the Haas Brothers

| Artist | Nikolai and Simon Haas (1984 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 2017 |

| Medium | Brass, and beaded chair |

| Dimensions (cm) | 161 x 111 x 99 |

| Current Location | Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York City, United States |

The Haas Brothers – twins Nikolai and Simon – are well-known for creating whimsical, colorful furniture and items influenced by science fiction, nature, and psychedelia. Using a range of materials, including porcelain, brass, resin, plexiglass, and fur, they construct bulbous, textured extraterrestrial creatures that appear to be pulled from a children’s story: Stools are shaped like hairy dogs, while tables have rounder feet and shapely legs.

The sleek lines of the Haas Brothers preserve vestiges of skilled workmanship. Their couches and chairs, for instance, have the look and attitude of odd and unusual animal-like psychedelic creatures.

Their iconic Spotley Cru chair, made of metal and beads in 2017, is an illustration of this. Since establishing their namesake firm in 2010, the team has exhibited in a variety of locales, including Miami, New York, Zürich, Los Angeles, Venice, and Tokyo, and their work has been bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Smithsonian Design Museum, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

As we have learned, functional art refers to art that serves a function other than decoration, and is art that has practical applications. The most typical example of utilitarian art is furniture. For many years, well-crafted furniture – chairs, tables, or lamps – has been collected not just for its shape and style, but also for its utility. Similarly, door knockers, knobs, and doors are being collected for their art form as well as their functional use. Table setting elements such as candle holders and mirrors are examples of utilitarian art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Functional Art?

A functional work of art is one that has a function other than being aesthetically and/or conceptually pleasing or intriguing. It’s functional art that you can wear or use. There is functional art out there, but many people are perplexed by the phrase. Because it demonstrates how beauty may be interwoven into commonplace items, functional art frequently inspires surprise, wonder, and even inspiration.

What Is the Definition of Functionality?

The utility or functionality of anything is its usefulness, or how efficiently it executes its job. For example, if you can’t get your new smartphone to send simple text messages, you could doubt its functioning. Functionality varies, but is present in everything from chairs and tables, to books and online interfaces.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Functional Art – When Artists Make Utility Their Concept.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. May 24, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/functional-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 24 May). Functional Art – When Artists Make Utility Their Concept. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/functional-art/

Davis, Liam. “Functional Art – When Artists Make Utility Their Concept.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, May 24, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/functional-art/.

THANK YOU FOR SHARING THIS. Very informative. this will be of great help for me in discussing the topic to my learners.

You’re welcome, thank you for your feedback!