Futurism Art – Explore the Dynamic Art of the 20th-Century

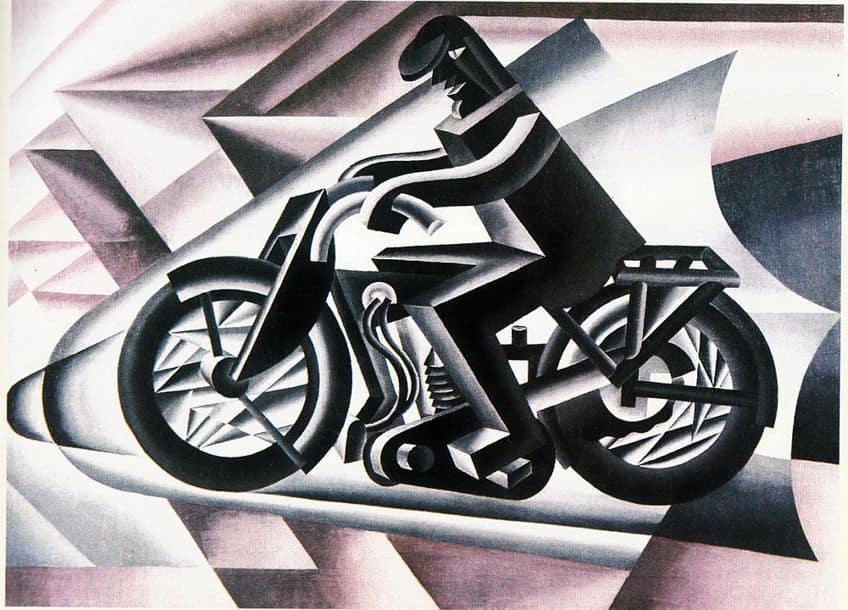

What is Futurism art? The Italian Futurism art movement celebrated modernity and progress, and the style spread across Europe, Britain, Japan, and the United States. Futurists focused on producing a dynamic and distinct vision of the potential future by incorporating the new technologies of the day, such as cars, trains, and airplanes, and depictions of urban landscapes into their Futuristic artworks. The style glorified the working class and speed, and developed into several art forms including Futurism paintings, Futurist drawings, and Futurism sculpture.

What Is Futurism Art?

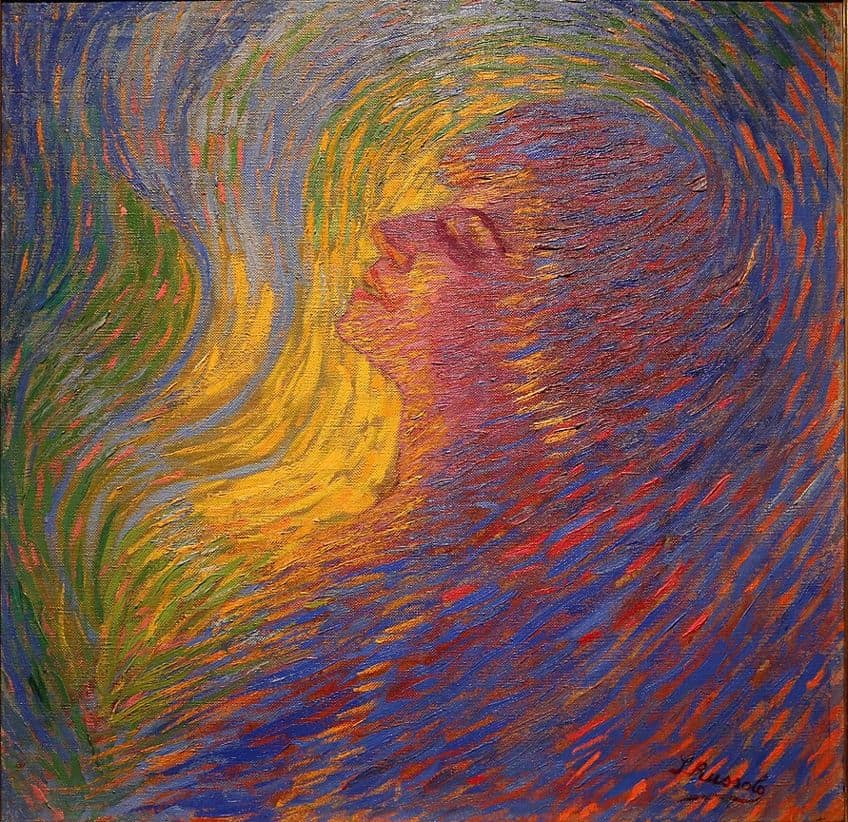

Futurists were interested in finding ways of expressing dynamism and movement in the works. The Futurism art movement utilized unique techniques to portray movement and speed, such as repetition, employing lines of force, and blurring. The use of lines of force was a technique adapted from the Cubists and would become a regular feature in Futuristic artworks. The movement not only produced Futurist drawings, Futurism sculptures, and Futurism paintings but also published many various manifestos to convey the group’s social and political ideas.

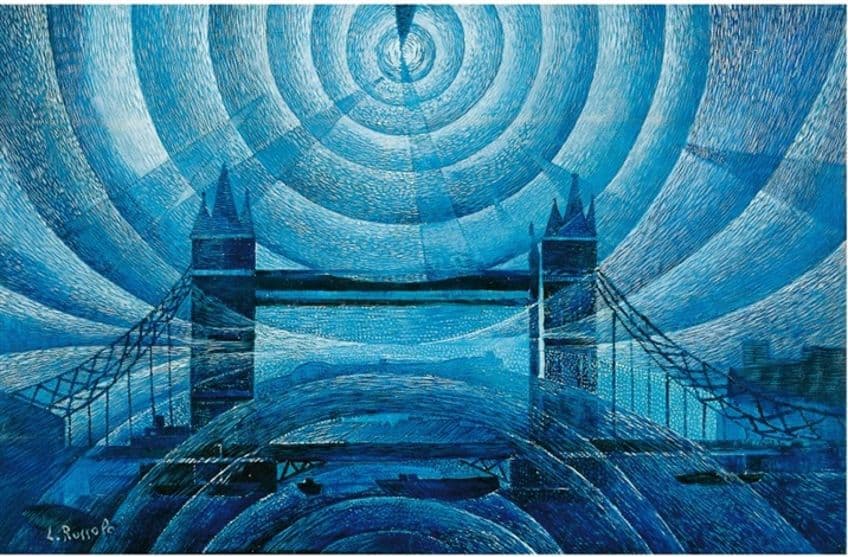

Tower Bridge (1929) by Luigi Russolo; Luigi Russolo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tower Bridge (1929) by Luigi Russolo; Luigi Russolo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The History of the Futurism Art Movement

Italian Futurism was largely inspired, and led, by Marinetti, the famous and charismatic poet. The Italian Futurism art movement gained prominence between 1909 and 1914 but was halted due to the First World War. However, after the war, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti revived the movement, which resulted in new artists joining who became known as the second generation of Futurists. While a few artists from Russia did initially engage with the Italian Futurism movement, Russian Futurism is generally regarded as a separate movement.

The futuristic style of the movement would subsequently influence German Expressionism and Dada, as well as anticipated Art Deco aesthetics.

The Early Development of Futurism Art

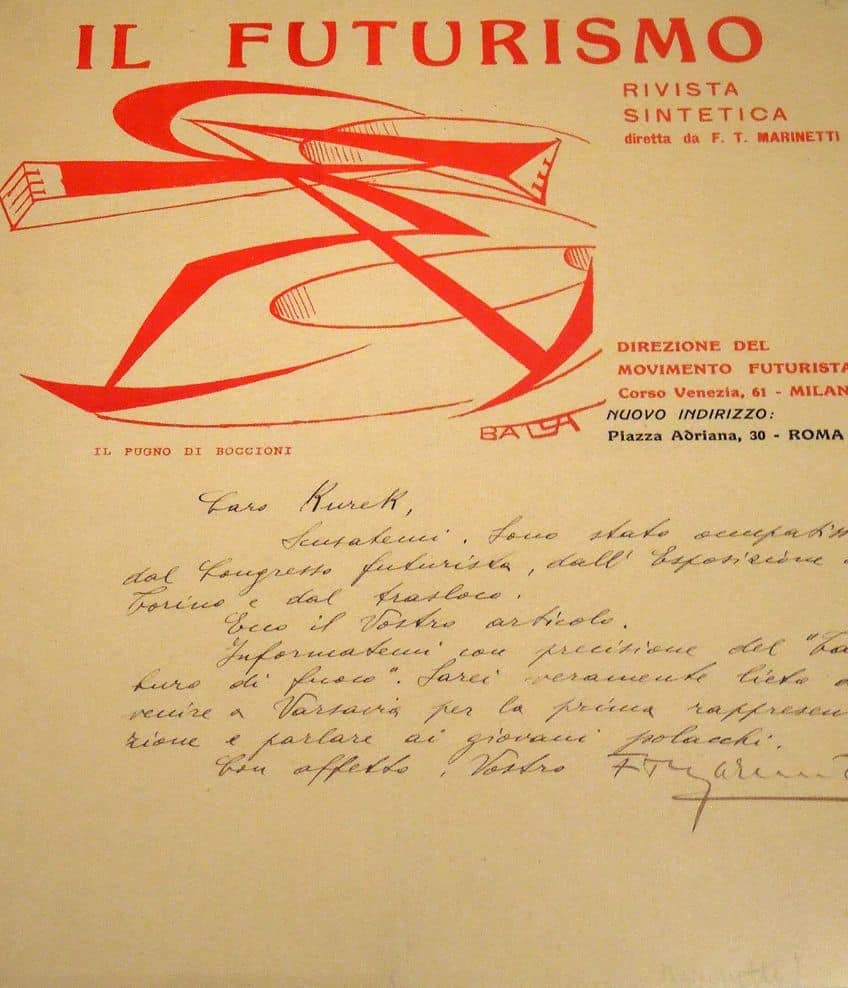

In February 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the poet, published his Futurist Manifesto, which many consider a crucial step in the early stages of the transformation of the culture in Italy. Initially printed in a small local Italian newspaper called La Gazzetta dell’Emilia, it was reproduced in France’s biggest newspaper two weeks later. The Futurists’ manifesto urged people to embrace mechanization, industry, and progress, and to demolish old and outdated institutions and ideas, and it would be the first of many publications released by the movement. Artists such as Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, and Gino Severini, were all influenced by the manifesto and believed that they could turn the ideas into futuristic artworks which would explore the properties of movement and space.

The movement emerged in Milan at first and then subsequently spread to Naples and Turin, with Marinetto promoting his ideas overseas in the years that followed. While the poet was regarded as the movement’s biggest promoter, theoretician, and writer, the Futurists’ artistic leader was Umberto Boccioni. Along with Luigi Russolo, Severini, Balla, and Carra, Marinetti wrote the Manifesto of Futurist Painters (1910), declaring their desire to eschew the senseless snobbishness of the past in an attempt to discover something original and support a world that was progressively driven by science rather than religion. The Italian Futurism art movement held its first public exhibition at the Exhibition of Free Art in 1911.

They sought to promote their futuristic art as well as assist in fundraising for an initiative that supported the unemployed citizens of the country called the Casa di Lavoro.

Any artist who wanted to display art that was not confined by limitation or derivation was invited to submit their works to the exhibit. Several of the artworks featured very fine brushstrokes and a bright color palette. Space was portrayed as fractured and fragmentary and the main subjects were speed, violence, and technology. Due to its cubist-influenced, advanced aesthetic, many regard one of the works on display at the exhibit, The City Rises (1910) by Boccioni, to be the very first Futurism painting. While many spectators and reviewers lauded the innovative subject matter of the artworks, others, such as the French critics from both artistic and literary spheres, expressed indignation.

The Various Influences on the Futurism Art Movement

In the years preceding the movement’s emergence, the members drew on a wide range of eclectic styles and methods informed by Post-Impressionism, and consequently, it took a long time for the Italian Futurists to discover their own unique aesthetic. Boccioni and Severin were introduced to Divisionism by Balla in 1901 when they were still studying in Rome. It was a technique that created an image by using only stripes of color and stippled dots (almost like analog versions of digital pixels). Futurists were highly inspired by the prismatic and bold colors of the Post-Impressionists, yet, it was Cubism that had the biggest effect on the Futurism art movement, despite members finding the overall aesthetic too “static” in subject and treatment. Several Italian Futurists, such as Russolo, Carra, and Boccioni, toured Paris in 1911, where they encountered the leading painters of the city such as Braque and Picasso, after which they started incorporating fractured planes into their artworks.

The Developments of the Movement Prior to the War

An exhibition held at the Parisian Bernheim-Jeune gallery in 1912 brought the movement into the public spotlight. The exhibit sparked debate at every level of urban culture – from reviews in elite periodicals to newspapers circulating in Germany, England, Russia, and France – and then subsequently toured Berlin, Brussels, and London. In the years 1913 to 1914, the style began to expand to other art forms such as Futurism sculpture, music, and architecture.

Seeking to express ideas of the mechanized body as well as action, Boccioni delved into Futurism sculpture to convey the style’s dynamic aesthetic.

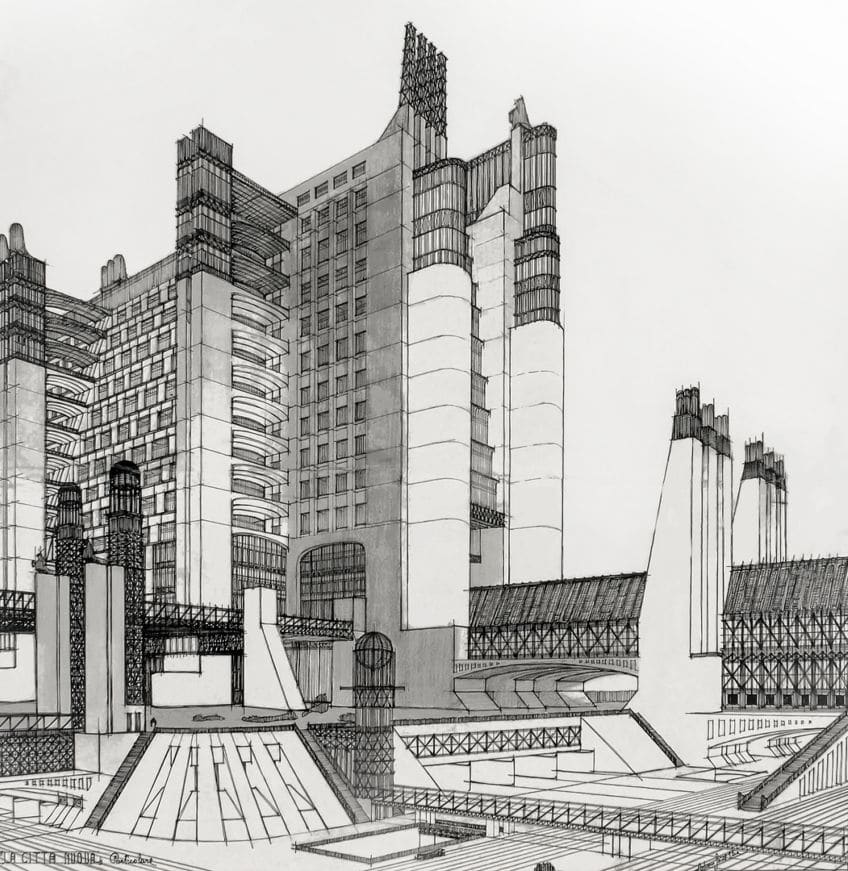

Others also shifted from creating Futurism paintings, such as Luigi Russolo, who wrote The Art Of Noises (1913), after moving from producing paintings to the production of musical instruments. In 1914, Marinetti published his Futurism poetry, and the innovative architect, Antonio Sant’Elia, became the first in his field to join the movement. The group began to fracture and diverge after, despite all this creative activity. Although Italy remained neutral until 1915, the onset of the First World War in 1914 significantly halted any further progress of the Futurism art movement.

After Futurism

Sant’Ella and Boccioni, unfortunately, died during the war, and Carra ended up in a military hospital following a nervous breakdown. While there, he met a fellow breakdown recoverer Giorgio de Chirico, and the two men would subsequently become members of the Metaphysical School of Painting. By the 1920s, Severini, who had stayed in Paris, had turned his focus toward Interwar Classicism and still-life painting. Marinetti formed the Futurist Political Party after the war, which aligned itself with the Fascist movement led by Mussolini.

Following the fall of the fascist party, he tried other ways to promote Futurism but the association with the fascists had caused irreparable damage to the perception of the movement as a whole. A group of new artists joined the group in the 1920s, including Gerardo Dotori, Fortunato Depero, and Ivo Pannaggi, despite the decline in popularity of the style. This era has become known as Second Futurism and was defined as being “decorative and more consistent”. The group began to create toys, ceramics, and poster designs during the Interwar period. Simultaneously, the view from high-rises and airplanes became fashionable in Futurism drawings and paintings.

The Legacy of the Futurism Art Movement

Futurism had a significant influence on many artists and movements from approximately 1912 until 1920. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner experimented with force lines to depict the motion and dynamism of crowd scenes, while Franz Marc included them in his paintings to add vitality to a subjective perspective. Many of the characteristics of Futurism may also be seen in Explosion (1917) by George Grosz.

The emergence of the Vorticist movement in England was greatly influenced by Futurism, which also included T.E. Hulme, Ezra Pound, David Bomberg, Wyndham Lewis, and Jacob Epstein.

It also influenced the emergence of modernism in the United States, mainly through the artwork of Joseph Stella. Futurist sound poetry and performances are believed to have influenced Dada. The designs of Antonio Sant’Elia anticipated Art Deco designs and influenced American architects such as John Portman and Helmut Jahn.

The Mediums and Concepts of Futurism Art

Futurists aspired to produce artworks that conveyed motion, or dynamism, as a means of expressing the frantic pace of modern life. Dynamism was generally represented by picture fragmentation, compositional turbulence, vigorous brushwork, and receding or emerging elements. As a result, Futurism art typically concentrated on topics that moved quickly and incorporated modern technology.

The Influence of Modern Warfare

“We want to celebrate war – the only remedy for the world – patriotism, militarism, the violent gestures of anarchists, the beautiful thoughts that kill”, Marinetti stated in the original Futurist Manifesto. This inflammatory statement sprang from his conviction that the history of Italy and Europe should be forcefully wiped away to make space for new ideologies. He also regarded contemporary technology as a weapon of war, believing that a thundering vehicle that seems to be powered by machine-gun fire is more magnificent than an ancient Greek sculpture.

As a result, representations of dynamism produced before the war were quickly adapted to the conflict.

The bombardments generated great excitement among the Futurists. They considered this to be a stimulus for their work as well as putting into reality what they had preached in various ways. As they followed Marinetti’s instruction to attempt to experience the war pictorially, analyzing it in all its aspects, violence and conflict became a major focus for their art. There are fewer Futurist paintings from the First World War than one might think because some of the group’s members entered the war as volunteer helpers, with Boccioni, Sant’Elia, Russolo, and Marinetti enlisting in the Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists, and focused on combat instead of art.

Film and Photography

Futurists were drawn to photography because of their fascination with movement. The three Bragaglia brothers developed photo-dynamism, images that depicted a person in motion from right to left with areas blurred to represent movement, inspired by the movement studies of Etienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge. Balla was a big admirer of the new technology, and several of his paintings look like photos with certain elements blurred by motion. Futurists regarded any action as the confluence in space and time of several extremities, instead of the activity of a single limb. The Bragaglia brothers were dismissed from the Futurists in 1913, largely for promoting photo-dynamism as a separate movement, however, they both continued to create in a similar style outside of the official movement.

The Futurism art movement disregarded photography as a consequence of the exclusion of the brothers until the 1930s, when a new school of photographers arose, embracing multilayered negatives and photomontage. Because of the Futurists’ fixation with movement, cinema was a suitable medium for experimentation while also meeting the group’s criteria for embracing new technologies. The Futurists created a few pictures between 1916 and 1919, but only Thais (1916), directed by Anton Giulio Bragaglia, survived. Despite portraying a typical scenario, the Futurist influence in the film is evident in the extremely stylized design and the incorporation of abstract elements. Enrico Prampolini’s film sets used bold black and white geometrical shapes as well as symbolism, and their design impacted the German Expressionism cinematic style.

The Spread of International Futurism

Rena Zátková, a Czech artist, resided in Rome for 10 years and trained under Balla. Pile Driver (1916) was described as “a work that embodies the static rhythm and movement of machinery and industry” by Jan Velinger, an art critic. She was most recognized, though, as a Kinetic Art innovator associated with the Russian avant-garde. Some of Joseph Stella’s early works are regarded as part of the Futurist canon in the United States, although his later works were equally influenced by the color palette of Fauvism and the multiple perspectives featured in Cubism. In Japan, recognition of Marinetti’s works and the several manifestos released by the movement around the First World War aroused great interest in Futurism.

Russian Futurist leaders Viktor Palmor and David Burliuk visited Japan in 1920, and their influence culminated in Japanese modernism becoming a weird and intricate mixture of Russian and Italian Futurism.

Although Italian Futurism has been recognized for influencing Russian Futurism, artists such as Lyubov Popova, Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, and David Burliuk strongly rejected this claim. Russian Futurism was far more literary and less visual than its Italian counterparts, with typography and text dominating most of their works. While Russian Futurism established its own styles and ideals, promoting a return to Russian traditions while accepting modernity, it had many similarities with Italian Futurism, especially in its portrayals of urban life and dynamism, as well as its glorification of the working class.

It is incorrect to claim that the Italian movement had no impact on the Russian movement, though. Between 1909 and 1913, representatives of the Russian Futurists went around Europe, with poets such as Valery Bryusov, Alexander Blok, Max Voloshin, Andrei Biely, and Nikolai Gumilev all visiting Italy. Bryusov, in particular, established connections with Italian Futurism and had his poetry published by Marinetti. As a result, Marinetti was keen to claim the Russian movement as a direct descendant of his own movement; nevertheless, this claim created a divided and unhappy relationship between the two organizations, and when Marinetti visited Russia for the first time in 1914, he was received with disdain and derision.

Notable Futurism Artworks

Now that we have covered the history and styles of Futurism art, we can examine a few of the most notable Futurism paintings and sculptures. These artworks celebrated technology and modernity and steered away from the traditional subject matter.

They focused on motion and speed, producing fragmented scenes using strong lines of force.

The City Rises (1910) by Umberto Boccioni

| Artist | Umberto Boccioni (1882 – 1916) |

| Date Created | 1910 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 199 x 301 |

| Current Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

When it was exhibited at the Exhibition of Free Art in Milan in 1911, this innovative piece launched Futurism. The artwork blended Post-Impressionism’s brushwork and blurry forms with the fragmented images of Cubism. It portrays the development of Milan’s new power plant. An enormous red horse leaps forward in the middle of the frame, as three men, their biceps strained, attempt to control it.

The blurry main figures of the horse and men, painted in brilliant primary colors, become the main focus of the frenetic activity that surrounds them, indicating that change comes from disorder and that everybody, including the observer, is caught up in the transition. Horses and humans are natural forces set against and united with one another in a profound confrontation from which Boccioni must have expected something innovative to develop.

Boccioni depicts modern work as a beautiful war with the past in order to establish a better tomorrow.

Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1911) by Carlo Carra

| Artist | Carlo Carra (1881 – 1966) |

| Date Created | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 199 x 259 |

| Current Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

This artwork honors Galli’s burial, an anarchist slain during a protest. Hundreds of people, including children, turned out for his funeral march, which was led by a group of anarchists. The image depicts the moment when police on horses attacked the march. Carrà was at the memorial service and ended up finding himself involuntarily in the center of it; he saw the coffin sway alarmingly on the pallbearers’ shoulders; he saw horses go crazy, lances and sticks clashing; it appeared to him that the dead body could have fallen to the floor at any instant and the horses would just have crushed it.

He was so moved by what he saw that he drew it as soon as he returned home. Galli’s coffin is covered with red material and hoisted aloft by anarchists represented in black in the middle of the image. They charge forward with determination at a barricade of police depicted on the left.

Rays of light shine from the coffin, lighting the darkness, uniting the masses of people, and highlighting Galli as the focal point of the piece, alluding to his role in sparking the conflict.

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) by Giacomo Balla

| Artist | Giacomo Balla (1871 – 1958) |

| Date Created | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 89 x 109 |

| Current Location | Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, United States |

This amusing artwork depicts a woman walking her little black Dachshund down a sidewalk. The woman’s feet and black folds at the bottom of her dress, as well as the dog’s tail, feet, and floppy ears, are multiplied and represented in varied degrees of opacity and transparency in an extreme close-up.

The delicate metal leash transforms into four parabolic arcs that connect the dog to the woman. This repetition and reproduction of the moving parts provide a sensation of forward movement that contrasts with the diagonal lines of the sidewalk. There aren’t many earlier artworks that show us such a close-up in such a dramatic way. Balla chose a topic that Impressionism specialized in, but he selected only one detail, an almost randomly picked segment, and made it the focal point of the entire painting.

A trifling subject is elevated to the position of the main theme.

Dancer at Pigalle (1912) by Gino Severini

| Artist | Gino Severini (1883 – 1966) |

| Date Created | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil and sequins on sculpted gesso on artist’s canvas board |

| Dimensions (cm) | 69 x 49 |

| Current Location | Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland, United States |

The dancer in the center of the artwork is made up of a dynamic convergence of lines and flowing cloth. Four stage lighting beams zoom in on her, accentuating her as the focal point of the painting, while her swift, rotating motions spread out in concentric rings to the limits of the pictorial plane.

Each of these circular layers comprises fragmented representations of performers, instruments, spectators, and patterns resembling musical notes, capturing a sense of the environment in which she performs. Severini frequently included three-dimensional components in his works, resulting in canvases that were a cross between sculpture and painting. This approach gives the painting a feeling of texture and shape, making it feel more tangible in certain aspects.

It also produces contradictory impressions for the observer when the artwork is viewed from different angles and viewpoints.

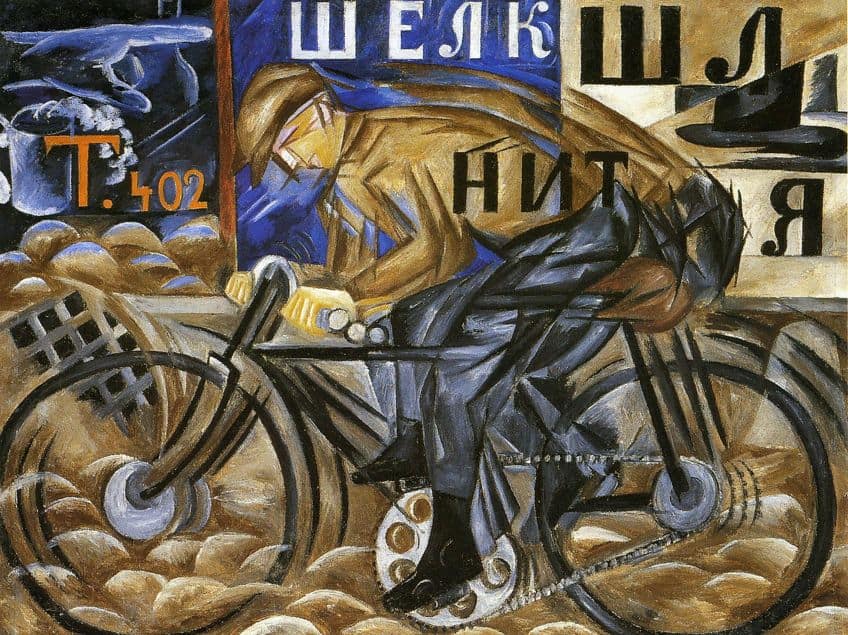

The Cyclist (1913) by Natalia Goncharova

| Artist | Natalia Goncharova (1881 – 1962) |

| Date Created | 1913 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 78 x 105 |

| Current Location | The Russian Museum, St.Petersburg, Russia |

Goncharova was regarded as a significant figure in the Moscow Futurists and a pioneer of the Russian avant-garde. She portrays a cyclist riding by businesses with advertisement advertising boards in this image. The prominent lettering on these posters reflects the Russian Futurist obsession with print, writing, and typography.

The cyclist’s legs, feet, and body, as well as the bicycle’s wheels and frame, are multiplied to convey a sense of forward velocity as well as the jarring vibration of the wheels on the cobblestones. The painting establishes a contrast between the past and the present by juxtaposing the vintage cobblestones with the modernism of the surroundings and the bicycle. The flat cap of the cyclist, which resembles cobblestones in shape and color, identifies him as a Russian laborer and juxtaposes him with the top hat of aristocracy portrayed in the advert behind him.

While repeating concepts of the significance of workers, his more realistic rendering of the cyclist as an average man on his route to work distinguishes him from Italian Futurism, which concentrated on cycling as an aggressive sport.

Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1914) by Joseph Stella

| Artist | Joseph Stella (1877 – 1946) |

| Date Created | 1914 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 195 x 215 |

| Current Location | Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, the United States |

The Coney Island amusements, including its famous roller coaster, are represented in this vividly colored kaleidoscope of spinning cones, diagonals, and elliptical forms, which the painter described as “an extreme arabesque – its soaring crowd and the rotating machines producing violent, threatening pleasures”. A heady sense of exuberance is produced by the fragments of vividly colored lights, attractions, banners, and the Mardi Gras crowd. Although this piece is obviously futurist in style – with its force lines, sense of motion, and subject – it subverts the group’s work in other subtle ways.

The term “Battle” in the title refers to the Italian canon, which frequently represented development as a conflict, but in this case, the fight is between each feature for the notice of the working-class patrons of the amusements. Stella also honors the proletariat, but in this depiction, they are playing rather than developing future infrastructure. As a result, Stella imbues Futurism with a particularly American flavor, presenting futuristic technology as delightful and engaging.

This was Stella’s first significant Futurist piece, as well as the first important American piece in the style.

Speeding Train (1922) by Ivo Pannaggi

| Artist | Ivo Pannaggi (1901 – 1981) |

| Date Created | 1922 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 100 x 120 |

| Current Location | Fondazione Carima-Museo Palazzo Ricci, Macerata, Italy |

As a train approaches the spectator diagonally, it starts to dematerialize, breaking into circular and diagonal planes with various degrees of opacity. The painting depicts the sensation of being near a train as it passes by, capturing the overpowering noises, images, and action. Concentric circles spinning in expanding arcs in the middle left of the canvas produce a vortex of velocity that appears to press down on the observer. Trains were viewed as emblems of modern dynamism by Futurist painters, but Pannaggi’s painting also depicts Italy’s efforts to modernize in the 1920s, when the rail system was changed to electric, allowing for record-breaking speeds.

Pannaggi joined the movement in 1919 when he displayed two of his Futurism paintings at Casa d’Arte Bragaglia, which were lauded by Balla and Marinetti. He argued for an aesthetic “based on machinery – gears remove the foggy and indecisiveness from our vision, making everything more acute, definite, aristocratic, and keen. We realize that we, too, are machines, that we, too, have been automated by our environment “.

That about wraps up our look at the Futurism art movement. Futurists embraced technological breakthroughs, such as the machine and any sort of automated vehicle, viewing them as symbols of development and modernity. They abandoned traditional forms of art in favor of experimenting with new methods and materials. The Manifestos of the Futurist art movement were written affirmations of the movement’s principles and intentions. They believed that in order for a new form to rise, the old had to first be violently destroyed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Futurism?

While many art styles were preoccupied with tradition, the Futurists were always looking forward to the future by embracing the advances of modern technology around them. The Futurism art movement was a particularly impassioned critic of the past, even among other modernist groups. This was because the burden of historical culture was especially oppressive in Italy. However, following the atrocities of the first World War, many artists discarded avant-garde ideas of futurism and other pre-war movements in favor of more conventional and comforting methods. The movement utilized techniques that would add a feeling of motion to their works, such as blurring details. They also multiplied certain elements over and over to create a sense of motion, such as the limbs of humans or the wagging tail of a dog.

What Did the Futurists Believe?

They anticipated that new technology would disrupt society and transform culture and the arts. They abandoned conventional creative forms and cultural ideals in an attempt to break free from the past’s restrictions. Futurists stressed the significance of speed and movement in both the natural and social worlds, and they attempted to capture this dynamism in their art and writing. They also highlighted the value of individuality and the artist’s function as a prophet and revolutionary. Futurists were social and political critics who tried to question the mainstream political and cultural beliefs of the period.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Futurism Art – Explore the Dynamic Art of the 20th-Century.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 21, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/futurism-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 21 August). Futurism Art – Explore the Dynamic Art of the 20th-Century. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/futurism-art/

Davis, Liam. “Futurism Art – Explore the Dynamic Art of the 20th-Century.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 21, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/futurism-art/.