Famous Greek Statues – Learn All About Ancient Greek Artifacts

The world’s most famous sculptures are derived from the ancient Roman period and include works classified under the Classical, Hellenistic, and bronze ages. The depiction of the human form was the most important subject in ancient Greek art in addition to various mythological deities and figures. This article will outline everything you need to know about the most famous Greek statues and why they are so highly recognized.

Ancient Greek Art and Sculpture

Sculpture is the last surviving form of fine art from the ancient Greek period, which encompasses pottery, statues, monuments, and other sculptural vessels. Greek art can be understood as evolving in four different periods, namely, the geometric, archaic, classical, and Hellenistic art periods. Instead of referring to art found under the ancient antiquity section of Greek art, the proper term is known as Greek Neolithic art. Following this, the Bronze age gave rise to Aegean art, which includes art from different cultures that existed during the bronze era.

The Geometric art era can be pinpointed to have begun around 1000 BC but since so little is known about this period, it is classified as the Greek Dark Age.

Around the 7th century BC, the Archaic style emerged and was characterized by the presence of black figure paintings found on vases. Moving forward to 500 BC, the Persian wars marked the transition of the Archaic period into the Classical period alongside the rule of Alexander the Great, which also separated the Classical era from the Hellenistic art era.

Different forms of art progressed and evolved at different rates, therefore, none of the periods can be marked for certain when it comes to the Greek world.

What helps historians figure out the different periods and methods of classification is the local traditions and cultures that enable researchers to pinpoint the source of origin of any Greek artwork. While many ancient Greek artifacts and paintings remain missing or destroyed, we are left with sculptures to work with.

Development of Greek Sculpture

During the Archaic period in Greece, the art sector saw a rise in the development of small figures crafted out of bronze, ivory, clay, and wood. The bronze figures usually consisted of human heads and griffins, which were utilized as attachment pieces for bronze cauldrons. The style of the human figures displayed geometric traits in their designs and was often depicted on ancient pottery. The figures would also be characterized by a triangular body with elongated limbs. Many ancient Greek artifacts such as animal figures featured in the 8th century. Many horse figures can be found at Olympia and Delphi, which were indicative of their votive function.

The oldest sculptures of Greece are made of limestone and date back to the middle of the 7th century. During this period, many free-standing bronze statues with bases were more frequent, and more complex figures like warriors and musicians arose.

Marble made its debut in Greek art around the early 6th century, which was accompanied by the first monumental statues. The functions behind statues from this time were dedicated as offerings to sanctuaries or as markers for graves. The largest and oldest stone statues, known as the kore (clothed female statue) and kouroi (nude male statue), borrowed artistic inspiration from the Egyptians and were characterized by blank stares and rigid bodies with their arms held strictly against their sides.

These figures evolved and more details appeared on the hair and muscles of the body. The development of these early figures is an excellent example of the transition from Archaic depictions to a more relaxed and life-like view. The Classical period witnessed the move away from the traditions of the Archaic period completely. This period also bore the glorification of the nude male form as well as large-scale, life-like sculptures. Marble was a popular medium for sculptors during this period.

Sculptures made in this era captured the still moment of characters, as though they were suddenly frozen only seconds ago. Here, facial expressions appear, and mood is introduced to sculpture.

Details on clothing also became less important as the focus was placed on emphasizing their flow with the body, as seen in the “wet look” or a wind-blown appearance. Bronze was also a popular medium, however, this was high in demand, and unfortunately, not many bronze sculptures remain from ancient Greek art as compared to marble.

Some of the best marble came from Naxos, Paros, and Pentelic, each with unique qualities and textures ranging from fine-grained to opaque and honey-colored. The stone was selected based on its ability to be sculpted and therefore many Greek sculptures were not polished but rather painted. In general, large-scale sculptures were not created using a single block of marble but were sculpted in separate sections and joined together on the main sculpture using dowels. The surface of marble sculptures would commonly be finished off with an emery powder from Naxos.

The final touches to Greek sculptures would be painting and decoration as well as finer features such as hair, skin, lips, and clothing.

A statue’s eyes would be inlaid with crystal, bone, or glass, and bronze was usually added to sculptures that depicted weapons such as swords and spears. A few statues were also found to have a bronze disc called a meniskoi positioned over the head section to prevent any damage from birds. Statues were not the sole forms of sculpture in Greek art. Other sculptural forms emerged as portrait busts, grave monuments, relief panels, and basins with female figures for legs called perirrhanteria.

Other forms of sculpture appeared in architecture on friezes, temple buildings, pediments, and treasury buildings from the late 6th century. The Romans admired Greek sculpture so much that they copied it extensively, so much so that more Roman copies remain than that of original Greek artworks.

The only difference being is that the copies lack the artist’s original splendor.

Color in Greek Sculptures

For many people of the 21st century, the idea of a classical Greek sculpture is often thought of as a shiny white marble nude of a man or woman. It is unthinkable then to conceive of the idea of Greek sculpture as anything but white marble. This stereotype is just as it is – a stereotype.

Many Greek sculptures were not just the plain white marble you see on the internet but it also encompasses polychrome works.

Greek sculpture also includes large-scale structures like buildings that were often painted (decorated) with colorful images. Even the early Greek artist would have considered a plain white David (1501-1504) by Michelangelo unfinished. It is only because of the tremendous weathering that many architectural structures have faced that we are only left with the faded and washed-out aesthetic. Many sculptures of ancient Greece once flourished with color. Hard to imagine, is it not? Some evidence can still be found in ancient Greek and Latin texts that detail records of painted figures in art.

Most signs of pigmentation are worn away due to weathering, which also affects the color of stone structures. Aging is also known to darken a painted surface and reveal stone as lighter. This results in color shadows that reveal to researchers where the paint was possibly once applied. This is termed indirect preservation. The durability of a pigment will also result in different outcomes regarding the color of the stone.

A durable pigment will protect the stone as opposed to a non-durable pigment, which will aid in wearing down the stone. This results in weathering relief and indicates where paint may have been applied.

Most artists incise a design onto the stone to serve as a guide and would sometimes do this with a pigment. Other ways to locate color on a sculpture is through observation using the naked eye or microscope, which would reveal the remains of color. Photographic measures include photographing an object under ultraviolet light to locate organic materials, often found in pigments. These organic materials range from oil and eggs to animal fat, acting as binders and/or coloring agents.

Famous Greek Sculptors

Among the many Greek artists, six sculptors received the most recognition for their artistic talents in sculpture. Below, you will find a list of the most famous sculptors in Greek art history. Most of the detailed accounts of information on Greek sculptors and famous sculptures have been derived from Roman writers like Pliny the Elder (c. 23 – 79 AD), also known as Gaius Secundus, who was also once the army commander of the Roman Empire.

Praxiteles (c. 370 – 330 BC)

Identified as the best sculptor of the fourth century, Praxiteles provided a touch of sensuality and grace in his sculptures, which had a tremendous influence on Greek sculpture to follow. According to one description of Praxiteles’ works, he imbued in his statues much passion.

His influential style was seen in later works during the Hellenistic period.

Lysippos (c. 370 – 300 BC)

Lysippos was regarded as one of the most popular sculptors during the reign of Alexander the Great and drew attention to the lifelike naturalism in his statues. Lysippos studied the work of Polyclitus and drew inspiration from his views on the male figure and divine proportion. According to Pliny the Elder, Lysippos created over 1500 bronze sculptures during his lifetime. What remains of that massive portfolio? Nothing but a few copies.

Scopas (c. 395 – 350 BC)

Scopas was a famous sculptor of the late Classical period. Scopas’ contribution to Greek sculpture was extremely powerful as he was the one who truly focused on emotional expression as an artistic theme. It is said that Scopas probably grew up in a family of artists since he was from the Greek island of Paros.

Scopas’ most notable works include Maenad located in the Dresden State Art Collection and Pothos, which is found in the Palazzo dei Conservatori collection.

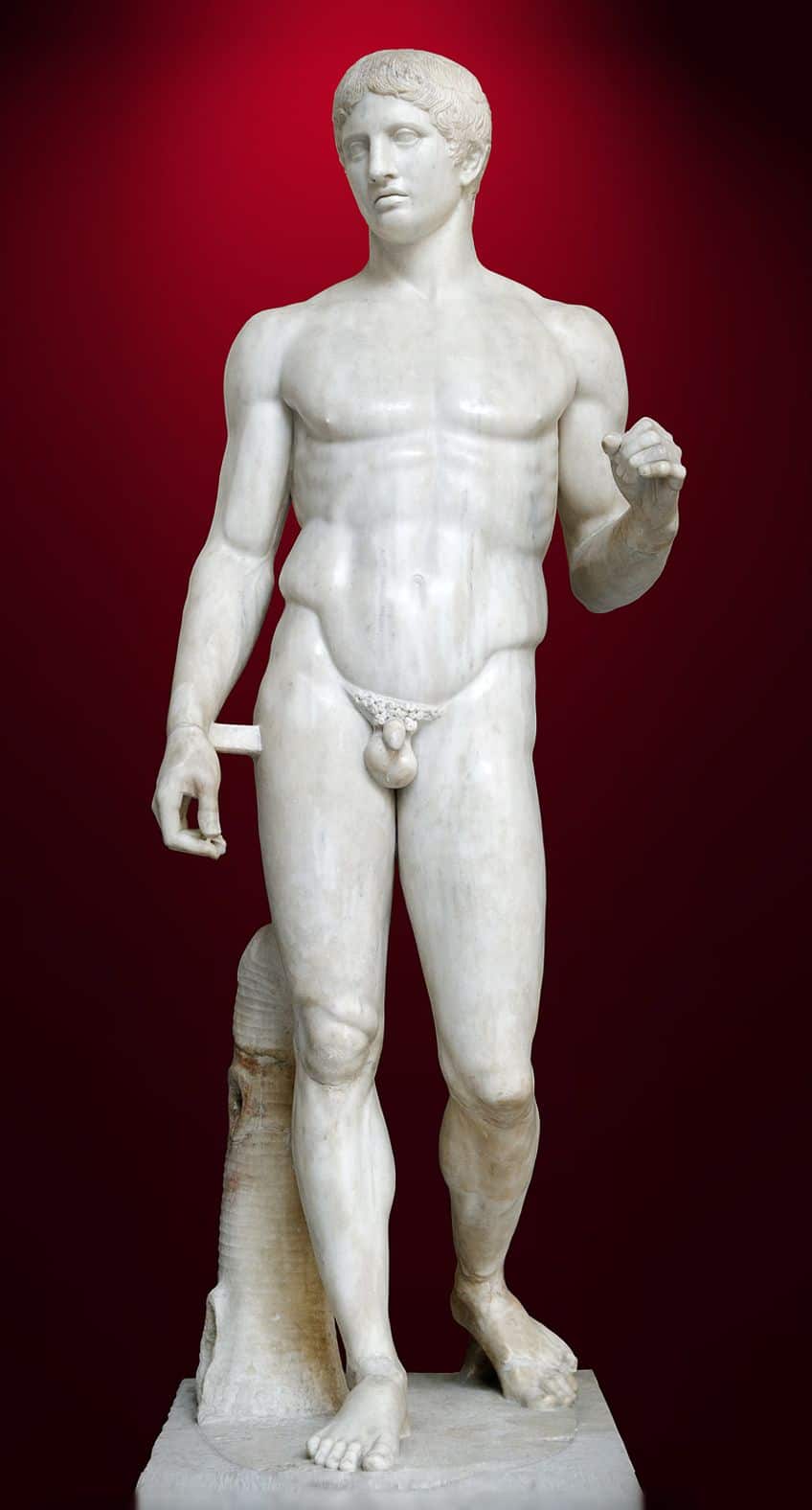

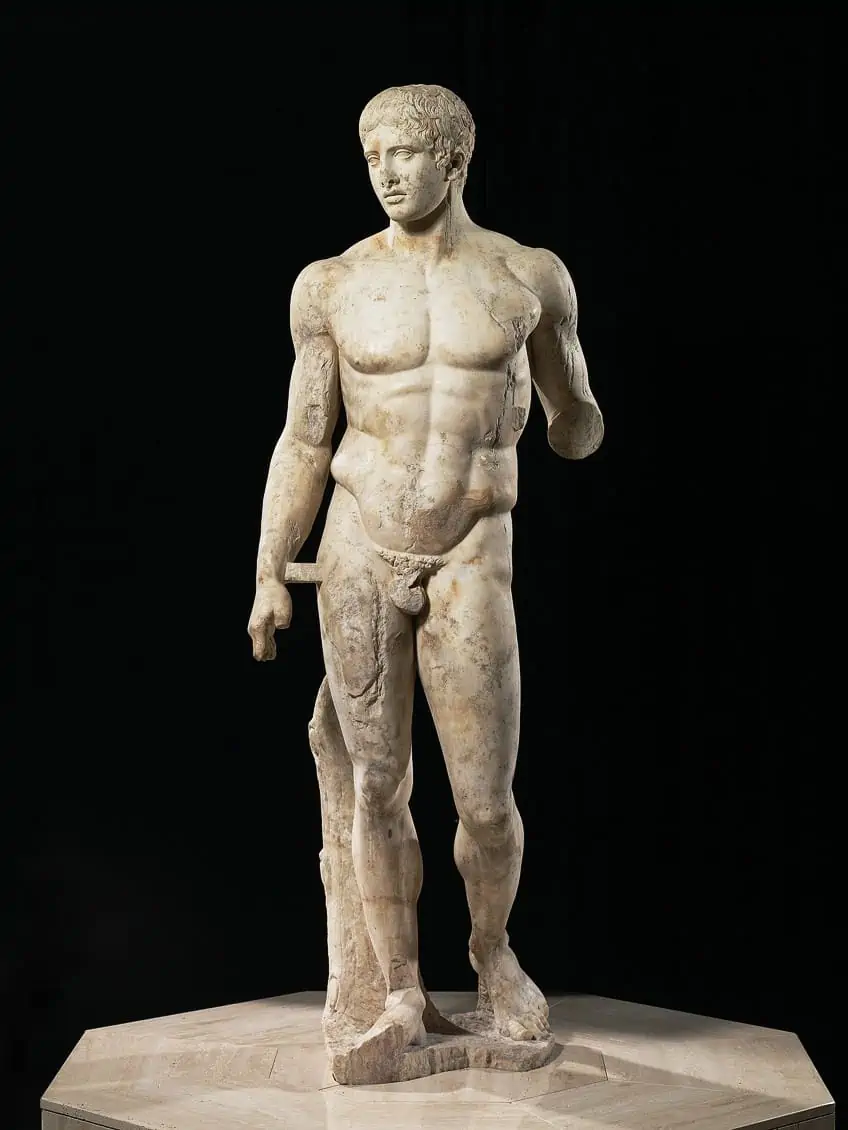

Polyclitus (c. 450 – 415 BC)

Also famous for his bronze athlete statues, Polykleitos (Polyclitus) set the tone in Greek sculpture with his high affinity toward aesthetics. His most precious sculpture, the Canon, was a theoretical gesture that included the ideal mathematical proportions (divine proportions) for the human body. This concept of achieving a balance between the relaxed and stressed parts of the body was called symmetria and was showcased splendidly in Polyclitus’ works through his mastery over the contrapposto pose, which freed the preceding sculpture style from rigid and unnatural frontal poses.

Phidias (c. 480 – 430 BC)

A man of many talents, the sculptor, painter, and architect Phidias is recognized as one of the most famous sculptors in ancient Greek art with both a prolific and tragic backstory. He was most famous for his construction of the Statue of Zeus at the Zeus temple in Olympia under a commission from the Greek statesman Pericles.

Phidias holds the title of being the sculptor who pioneered the Classical style.

Myron (c. 480 – 440 BC)

Myron was a senior to Phidias and was regarded as an innovative sculptor. According to praises from Pliny, Myron was the champion behind integrating movement with remarkable composition in Greek sculpture. Myron is most famous for his bronze statues of athletes in action.

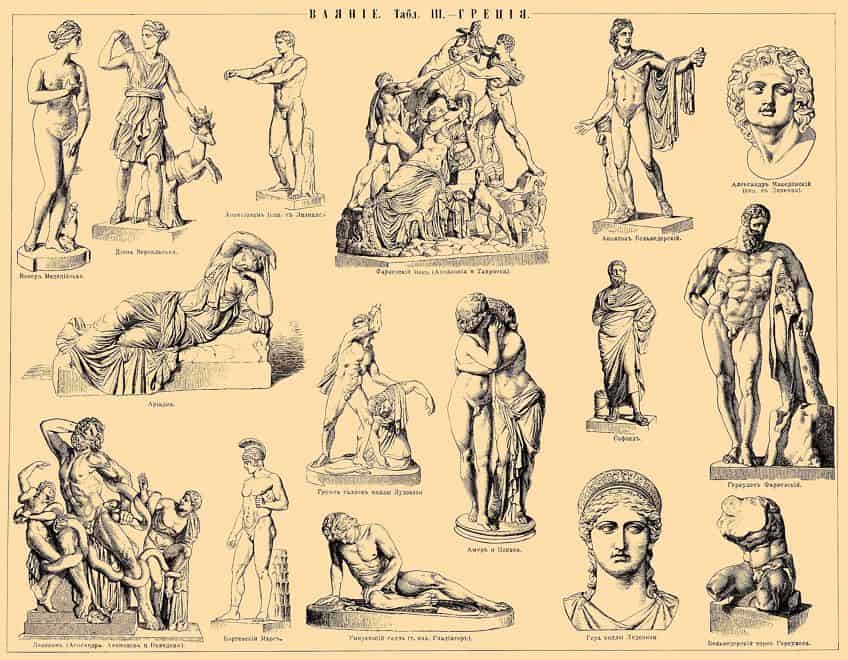

Top 10 Most Famous Greek Statues

Greek sculptures executed in stone and bronze are among the most recognized art forms from the ancient Greek period. From 800 to 300 BC, Greek sculptors borrowed inspiration from their Egyptian counterparts and the Near East for monumental works. The essence of Greek sculpture was aimed at the representation of the human form in all its perfection and was hyper-focused on demonstrating correct proportion. Below, we will explore the top 10 most famous Greek statues in art history.

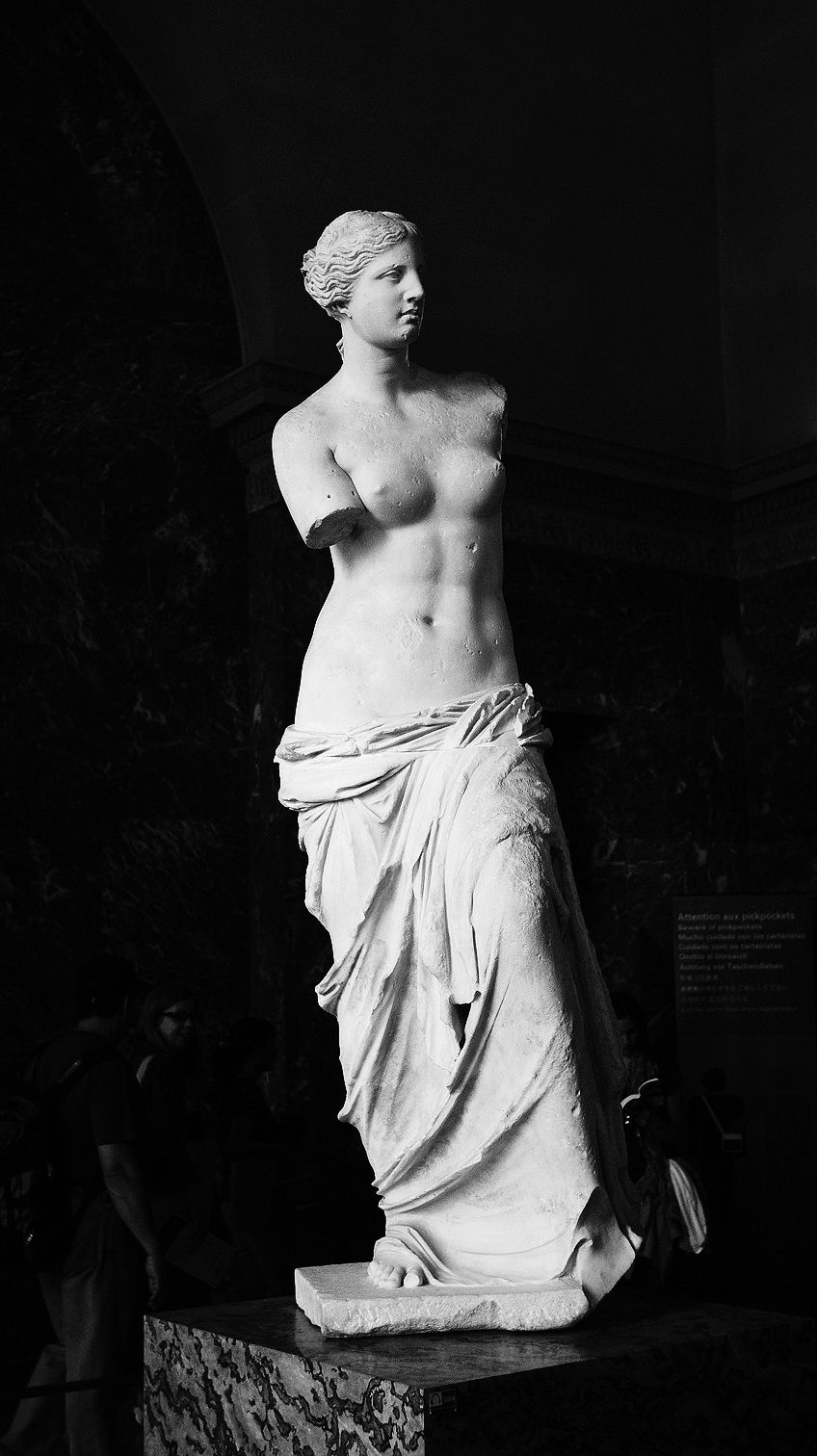

Venus de Milo (c. 125 – 150 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch

| Artist | Alexandros of Antioch |

| Date | c. 125 – 150 BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1820 |

| Place of Discovery | Milos, Greece |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 204 |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre, Paris, France |

Perhaps the most famous Greek woman statue, which also falls under the Hellenistic period is Venus de Milo (c. 125-150 BCE) depicting the Greek goddess, Aphrodite while the title suggests the Roman counterpart as Venus. Originally, the statue is said to have had two arms intact with both earlobes and her plinth.

While the original positioning of the figure is uncertain, archaeologist Elizabeth Barber believes that the posture of Aphrodite was probably a portrayal of the deity’s hand spinning.

The statue was unearthed in 1820 by a Greek farmer who found the statue buried within the ruins of Milos (now present-day Trypiti) on the Aegean Island of Milos. The ruins were said to once be an ancient theater near the capital of the island. According to the account of the statue’s discovery, the statue was found in a small cave covered with a massive slab and hidden away. The marble statue was discovered in two pieces alongside its inscribed plinth, fragments of the arms, and several pillars with heads.

The discovery was regarded as incredibly significant and was even subject to Nazi threat during World War II. The statue was housed in the Louvre in Paris during this time and the French art world was already facing huge losses about the return of looted collections. This is where the Louvre lost other famous Greek sculptures like Laocoön and His Sons. This did, however, allow for Venus de Milo to shine as the new iconic statue of France. The statue gained further elevation in status through its promotion in French propaganda during the 19th century.

The figure of Aphrodite had become the ultimate symbol of beauty well into the late 19th century. The statue has also since been featured in many popular culture references.

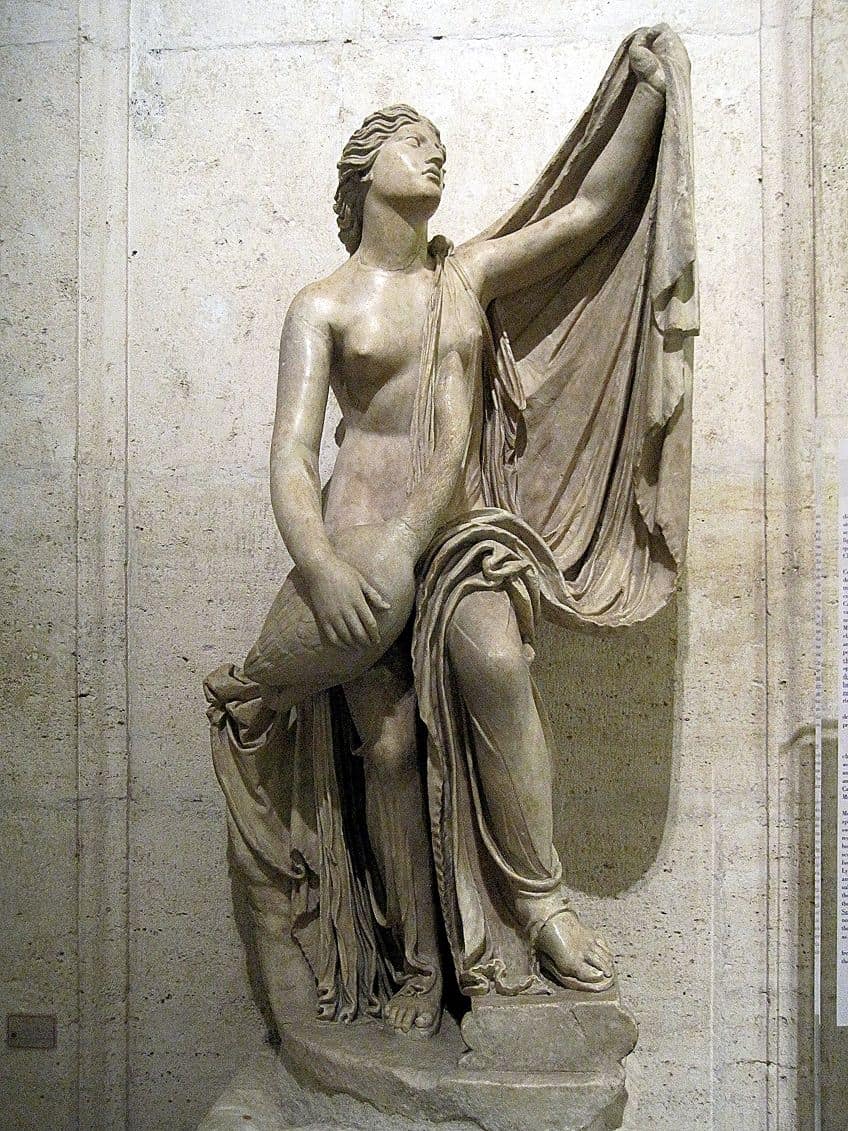

Nike of Samothrace (c. 295 – 290 BCE) Commissioned by Demetrius Poliocretes

| Artist | Unknown |

| Affiliation | Demetrius Poliocretes |

| Date | c. 295 – 290 BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1863 |

| Place of Discovery | The Samothrace Temple Complex, Samothrace |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (m) | 2.75 (5.57 total monument size); 2.4 (without head) |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre, Paris, France |

Situated in the Hellenistic period of Greek art, this famous Greek woman statue was most likely commissioned by Demetrius Poliocretes and represented the mythological deity called Nike, the goddess of victory, characterized by the symbol of her wings.

Constructed out of Parian marble, the figure shows the winged goddess stepping off the bow of a war vessel.

The goddess is adorned with a chitôn, which is known to be a light fabric garment likened to the tunic. The chitôn also has a folded flap and appears belted beneath her chest. Her lower body is covered by a himation, which is a thick mantle seen rolled up to her waist and untied on her left leg. One end of the himation falls between her legs and the other end is depicted as blowing in the direction of the wind behind her. Her himation appears to fall off her body but the parts that still clothe her are only held up by the invisible force of the wind.

Nike’s unknown sculptor seemed to be a master of carving out drapery and reveals the different ways in which the folds form against the goddess’ body, especially towards her belly. The drapery on the right side of the statue is not as detailed as the left side and only details the primary lines that give the drapery form. As Nike advances, she steps forward on her right leg. The goddess was depicted as not walking but having just descended from the air since her wings appear to spread out. Nike is seen making the gesture of salvation to indicate victory.

It is assumed that the original sculpture positioned the goddess in the standard naval position, the stylis. The statue was created with the intention of being viewed from the right (from the position of the spectator).

What makes this sculpture so special? The art historian H. W. Janson described the statue as being unlike the Near Eastern or early Greek sculptures in that this statue draws attention to the imaginary space around the figure instead of the figure itself.

The focus was on the wind that carried the goddess and which also appears to be against her as she strains her body to remain steady. The imaginary space elevated the significance of this statue during its existence and alludes to the metaphors of destiny, divine assistance, grace, and struggle. The relationship between Nike’s body and the space around her became a common quality featured in many later Romantic and Baroque artworks almost 2000 years later. The Nike of Samothrace is therefore a statue crafted with skill and thinking way before its time and is also present in other sculptures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s David (1623 – 1624).

Hermes and the Infant Dionysus (4th Century BCE) by Praxiteles

| Artist | Praxiteles of Athens (c. 370 – 330 BC) |

| Date | 4th Century BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1877 |

| Place of Discovery | Temple of Hera, Olympia, Greece |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (m) | 2.12 (h) x 3.7 (b) |

| Where It Is Housed | Archaeological Museum of Olympia, Olympia, Greece |

Also known as the Hermes of Olympia, this fourth-century Greek statue was first discovered around 1877 among the temple ruins of the Temple of Hera in Olympia, Greece. The statue portrays the mythological duo of Hermes, the protector of Greek heralds and human travelers with the infant God of the grape harvest and winemaking, Dionysus. The maker behind this famous Greek statue is believed to be Praxiteles of Athens according to an account by the traveler, Pausanias. The statue is currently housed at the Archaeological Museum of Olympia and is considered a crucial display of Praxitelean art.

While also remaining the hot topic of debate among many historians, the statue is also considered one of Praxiteles’ lesser famous sculptures since no copies have been discovered.

Praxiteles sculpted the two-meter-tall Hermes and the Infant Dionysus out of the best Parian marble with a three-meter base. Hermes’ face and body were sculpted as highly polished and almost glowing, owing to the remark by John Boardman who draws connections to the many generations of temple workers who were female and probably in adoration of the male figure.

The sculpture appeared to be incomplete since the back of Hermes was found to display traces of the chisel and rasp as opposed to the polished front. Greece entered into an agreement with Germany in 1874 that allowed for the commencement of an archaeological excavation at the Olympian site, first excavated in 1829 during the French Morea expedition. Ernst Curtius headed the excavations conducted by the Germans in 1875 and by 1877, the discovery was made. Unearthed among the rubble and remains of the Temple of Hera were the torso, legs, left arm, and head of the young man, Hermes, lying against a tree hidden by a mantle.

The statue was found in an excellent preserved condition due to a thick layer of clay above it. The next six discoveries allowed for the recovery of the rest of the statue and the whole body as we see it today.

When the statue was discovered, the hair on Hermes seemed to contain traces of cinnabar, which is a mercury sulfate with a red pigment often used for painting and was most likely preparation for gilding. Some traces of cinnabar were also found on the sandal straps of the foot Hermes with signs of gilding. On Hermes sandal is also the motif of the Heraclean knot. The Hermes statue with Dionysus is currently still missing the right forearm and two fingers on the left hand. Dionysus is still missing both arms and the last section of his right foot. Only a portion of the base of the sculpture remains and was constructed out of gray limestone wedged between two marble blocks.

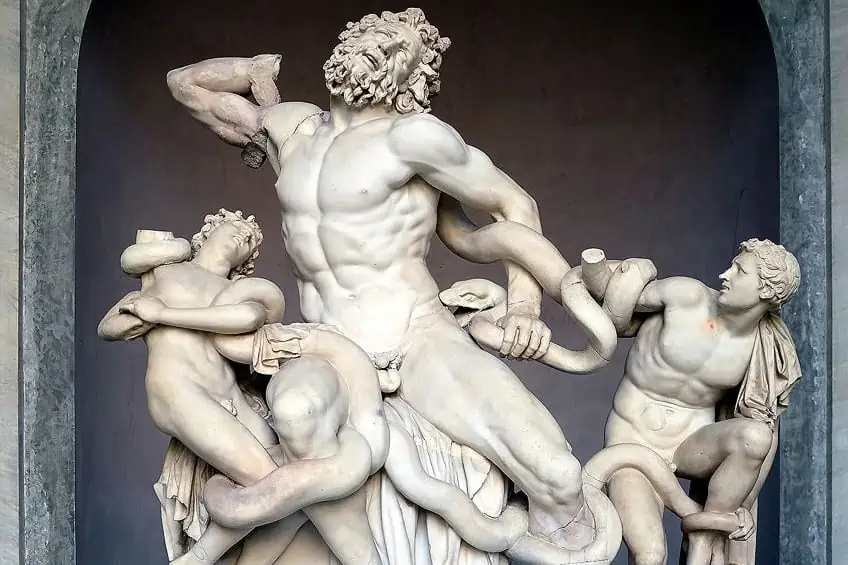

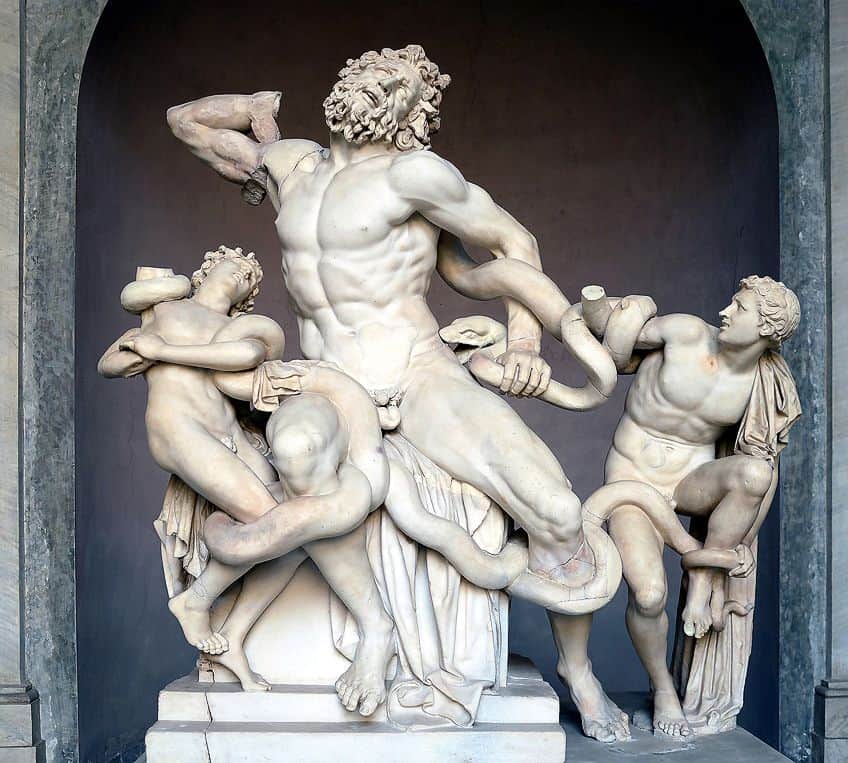

Laocoön and His Sons (323 – 31 CE) by the Rhodesian Trio

| Artist(s) | Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus |

| Date | c. 323 – 31 CE |

| Discovered Date | 1506 |

| Place of Discovery | Milos, Greece |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 208 x 163 x 112 |

| Where It Is Housed | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

Excavated in 1506, this iconic statue depicts Laocoön and His Sons being attacked by giant serpents. This famous Greek sculpture is the prized feature of the Vatican collection and is believed to have been commissioned by a wealthy Roman family. The Greek statue is believed to be the symbol of ultimate human anguish, seen in the facial expressions and scene that ensues in the sculpture.

The trojan priest is seen wrestling with the snakes that attack him and his sons and his facial expression re-emerged as a subject of reassessment in 2021.

Believed to be an anatomical mistake by even Charles Darwin, the emotion conveyed showcases Laocoön’s eyebrows and expression of anguish accompanied by the ripples of skin forming his expression of distress. This expression concerned many critics for years since the French neurologist claimed that the sculpture’s expression was “physiognomically impossible”.

The sculpture was first thought to have been a decorative element in the Roman Emperor Titus’ palace during the first century but the sculpture was unrecorded for many centuries after, making it difficult to track its provenance and value. The Roman writer, the Pliny the Elder, had more to say about the sculpture. He praised it as an artwork that was “preferable to any other production of the art of painting or bronze statuary”.

He also claimed that he knew of the sculptors and the process, describing the making of the sculpture as being constructed out of a single block of marble by three Rhodesian artists: Agesander, Athenodorus, and Polydorus.

The poet, William Blake also claimed that the sculpture was a forgery of a lost Hebraic masterpiece and that it once served as an adornment in the Temple of Solomon. The figures were also believed to be the God, Jehovah with his sons Adam and Satan. Blake was also convinced that these classical scenes were “corrupting creative consciousness” and he was moved to even deface a print of the sculpture.

The Dying Galatian (c. 323 – 321 BC) by Epigonus

| Artist | Epigonus |

| Date | c. 323 – 321 BC |

| Discovered Date | c. 1621 – 1623 |

| Place of Discovery | Gardens of Sallust, The Pincian Hill, Rome |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 168.9 x 226 |

| Where It Is Housed | Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy |

The Dying Gaul (c. 323 – 321 BC) depicts a warrior about to fall in his last moments of death with his face showing a painful expression and perhaps acceptance of his fate. This sculpture is one of the most famous ancient Greek statues and embodies the message of defeat and courage in the face of death. The statue is thus a celebration of the human spirit. Dying Gaul was sculpted by Epigonus of Pergamum, who was also written about by Pliny the Elder. Epigonus was a high-ranking sculptor (chief) at the court during the turn of the third century, which fell under the Attalid dynasty.

The sculpture was discovered alongside another sculpture, Gaul Committing Suicide with His Wife. The sculptures were not acknowledged as significant at first since no one recognized that they were depictions of Gallic warriors.

The warrior is seen with a torque around his neck, leonine hair, and a mustache, which was affiliated with Celtic tribes that the Greeks and Romans looked down upon. Gallic warriors were, however, commended for their ferocity and bravery, as marveled by Polybius, a historian saying that “they fought with nothing but their weapons” and that their appearance was also terrifying despite their nakedness – all well-built men in the prime of their life.

The image of the Dying Gaul became an iconic image and one of the most celebrated sculptures from Greek antiquity. The form also inspired many artists to replicate the work and established itself as a referential model for the display of strong emotion. The sculpture itself appeared to show traces of repair since the neck seemed to have been broken off at one point. The warrior’s enigmatic and untamed hair was most likely the 17th-century remodeling of his long hair, which was broken upon the statue’s discovery.

Before arriving at its final name, the sculpture also gained other titles such as Murmillo Dying, Defeated Gladiator, and Roman Gladiator.

Athena Parthenos (447 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist | Phidias (c. 480 – 430 BC) |

| Date | c. 447 BCE |

| Medium | Gold, ivory, wood, glass, copper, precious stones |

| Dimensions (m) | 11.5 (original) |

One of the greatest historical Greek sites and a tourist hotspot, the Parthenon, was established around 447 BCE during the reign of Pericles and was a home dedicated to the Greek goddess of war, Athena. The name of the temple, the Parthenon, originated from one of Athena’s epithets. The meaning of Athena Parthenos translates to “virgin”, while Parthenon refers to the house of Parthenos.

A master sculptor and friend of Pericles created this famous Greek statue, known as Athena Parthenos, around the completion of the Acropolis building.

This temple was made to store the ivory and gold statue that would serve as a symbol of Athens’ success in the Persian wars. According to a record by Pliny, the massive statue was approximately 11.5 meters tall and contained gold that weighed around 1140 kilograms.

The sculpture, although built on a wooden framework, was also decorated with ornate elements such as precious jewels, silver, glass, and copper. The cost was found to be an estimated 5000 talents, which converted to modern-day value equates to around $9 billion.

Identified as a cult statue, this famous statue had vanished for a certain period in history.

It was believed to have been transported to Constantinople where it was destroyed. Like many ancient sculptures destroyed due to unknown circumstances, this statue of Athena was copied and one can admire the once brilliant splendor of Athena Parthenos in other figures like the Varvakeion statue.

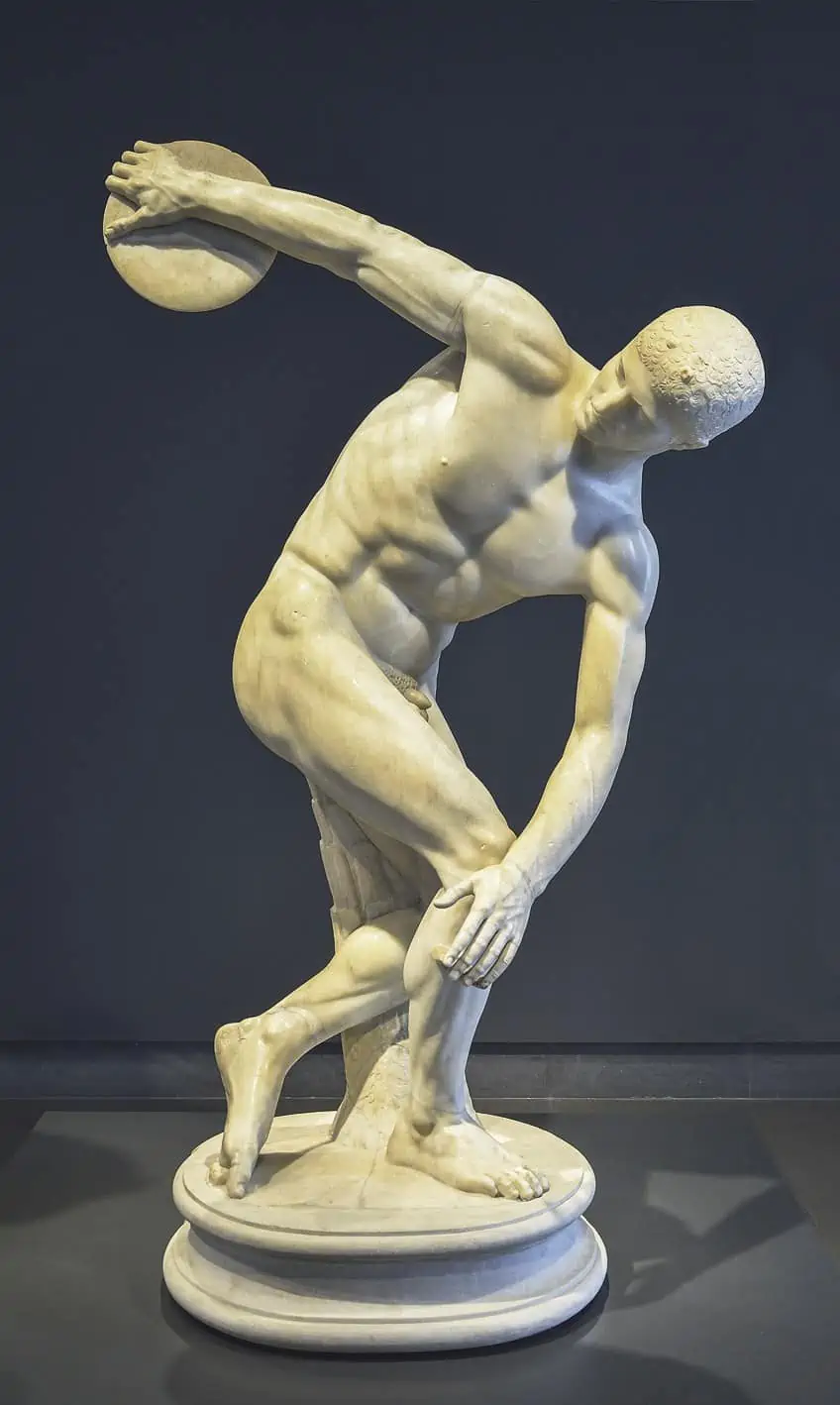

The Discobolus Palombara (460 – 450 BCE): Graeco-Roman Copy

| Artist | Myron (c. 480 – 440 BC) |

| Date | c. 460 – 450 BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1781 |

| Place of Discovery | Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli, Rome |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (m) | 1.70 |

| Where It Is Housed | Townley Collection, British Museum (copy) |

You may have recognized this famous statue by its image depicting a young discus thrower with his body contorted in the act of preparation for throwing the discus. This sculpture is a great example of the transition from Archaic period art to art found in the Classical period.

There are many copies of this sculpture but the original and first discovered sculpture is believed to have been created by an Athenian man named Myros.

The young discus player is seen releasing his throw as Kenneth Clark describes it as using “sheer intelligence”. The original bronze Greek statue was lost but many cheaper marble copies remain. This iconic image of athleticism is also associated with the male nude in Greek sculpture. You may often wonder why so many Greek sculptures are depicted nude. The easiest answer tends to be derived from the ideals of Greek art, that being, a focus on the perfection of the human form and beauty.

An education specialist from the Getty Villa Museum, Shelby Brown comments on this stating that the idealized male form was “developed in Greek art” and admired the “slender, ageless, and toned male figure with a full six pack and youthful face” without an expression or signs of aging. Nudity was also commonly associated with the display of heroes and mythological figures in Greek art.

Through art, the Greeks were marketing a new social norm. It was only until the fourth century that the idealized male nude image was interrupted by the female nude, Aphrodite.

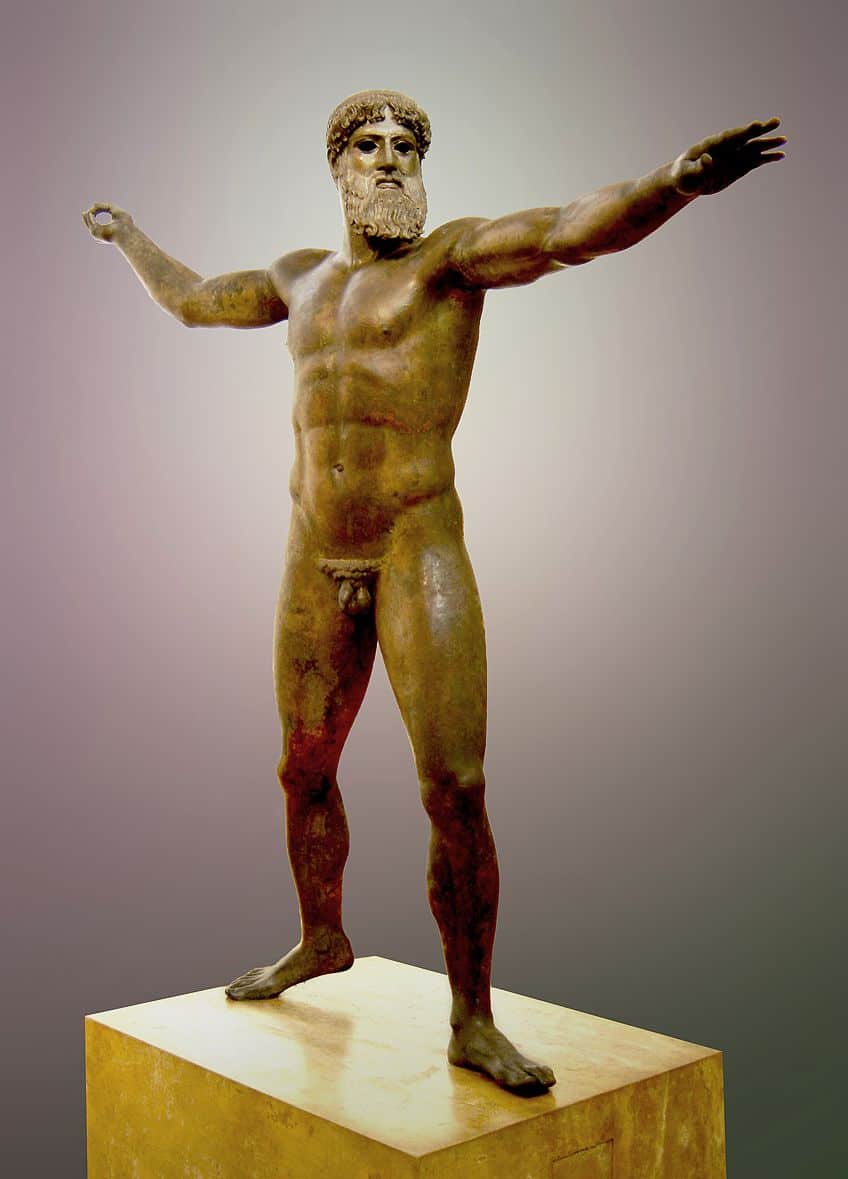

The Artemision Bronze (c. 460 BCE) by Calamis

| Artist | Calamis (5th century) |

| Period | Early Classical period |

| Date | c. 460 BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1926 |

| Place of Discovery | Cape Artemision, Euboea, Greece |

| Medium | Bronze, silver, copper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 209 |

| Where It Is Housed | The National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece |

Found in a Roman shipwreck around 1926 and excavated in 1928, this famous bronze Greek statue is believed to be created by a sculptor named Calamis. Not much is known of the artist’s life but he was famous for his sculptures of animals, especially horses, which according to Pliny, was unrivaled. The statue was discovered in two pieces and is believed to represent the Greek God of thunder, Zeus or Poseidon, the God of the sea.

The statue serves as a symbol of strength, beauty, and control. Due to the sculpture’s majestic sculptural quality, it is believed to represent Zeus.

The figure is depicted in a complete nude with the left arm and foot placed forward, presumably in the direction of the enemy. The figure’s right limbs are raised and appear bent to portray his movement. The weight of the figure is placed on the left side while the other side only lightly brushes the ground. It is as if the statue is in limbo, ready to take action. The detail on the bronze is immaculate with his facial hair carved meticulously.

The eyebrows were believed to be crafted out of silver while the eyes were made of another material, now missing, and his lips are crafted out of copper. The statue initially held a thunderbolt in the figure’s right hand and presumably a trident, if it were Poseidon. The sculpture was made using the wax method with each section of the statue cast separately and joined by welding.

It is assumed that this statue was created in a temple for Zeus as an earthly offering.

The Riace Bronzes (c. 460 – 450 BCE) by Myron and Alkamenes

| Artist | Myron and Alkamenes |

| Date | c. 460 – 450 BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1972 |

| Place of Discovery | Riace, Calabria, Italy |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 2.05 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia, Calabria, Italy |

This dynamic bronze duo was discovered in 1972 off the shore of Riace by a local snorkeler on vacation. The man who discovered the statues, Stefano Mariottini, recalled that he caught a glimpse of the left arm of the statue from the sand and was worried that he may have found the remains of a human body instead. When he touched it, he discovered that it was bronze and he then uncovered the rest of the first statue. Later on, he went on to locate the second bronze male figure and notified the cultural department of his find.

Another theory floats on the internet stating that the sculptures were found by a group of teenagers from Riace who approached the government finance office directly to claim the discovery.

Despite the debate on who found the statues first, the latter story is more widely accepted and even featured in the BBC’s 2005 docuseries How Art Made the World. Furthermore, there is a third bronze statue believed to have been reported by the snorkeler but also rumored that the piece had been stolen before the report and sold off to a collector overseas.

So, how did these two fine bronze men end up at the bottom of the ocean? It is believed that the statues were mid-transportation on a vessel that sank during a storm. No evidence has been found of a shipwreck but it was not far out of the realm of extreme possibilities that the statues were on their way to the local area nearby. In 2004, a team of Italian-American archaeologists embarked on an exploration of the coast and discovered the foundations of an Ionic temple. The expedition was executed using robotic vehicles deployed underwater, which offered great visuals but sadly, no sign of any other bronze artifacts.

The artists behind the sculptures are believed to be Myron and Alkamenes. The statues portray one young male as a warrior or even a God showcasing a proud expression and the other statue is of an older warrior with a gentle gaze and calm demeanor.

This bronze duo is considered a significant contribution to ancient Greek statues and falls under the transitory period from Archaic sculpture to Classical sculpture, indicated by the appearance of “impossible anatomy” and “idealized geometry” beneath a realistic surface. The figures are positioned in contrapposto with their weight placed on their back legs. The figures were also carved as very muscular yet their skin still retains a soft quality. This bronze duo is a culmination of not only movement but life.

Kore of Auxerre (650 – 625 BCE) at the Louvre Museum

| Artist | Unknown |

| Period | Archaic |

| Date | c. 650 – 625 BCE |

| Discovered Date | 1907 |

| Place of Discovery | Museum of Auxerre, Paris, France |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Dimensions (cm) | 75 |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

This small-scale limestone statue known as the Lady of Auxerre appeared at the Museum of Auxerre mysteriously and was discovered by a curator who had no idea as to the manner of how or when the statue arrived in Paris. The statue depicts a kore, which is a young maiden, which was also the name of Persephone, the Greek daughter of the goddess of agriculture and harvest, Demeter.

Many of these kore figures were once believed to be painted in bright colors and are one of the earliest examples of Greek sculpture.

Some of its Daedalic features include its emphasis on the front portion of the statue meaning that it was meant to be viewed from the front. There is also minimal depth to the body and the face appears mask-like with a plank-like body. The profile is therefore very simple. The face of the statue appears to be an inverted triangle with a U-shaped chin, resulting in a flattened head and a low forehead. The facial features include a pronounced eyebrow structure, thick lips, and large eyes.

The hair of the statue is said to be inspired by Egyptian sculpture, which appears stiff. The statue’s hair is carved in four tresses that are crimped at equal intervals and tied at the end with tiny knobs on either side. This provides a horizontal effect on the hair and the two axes form a grid. Despite the rigidity of the hair, the sculpture still has a gentleness to the hair portrayed by the curls on the statue’s forehead. The left arm is positioned against the figure’s body while her right arm is laid across her chest.

The gesture that the young maiden makes with her hand across her chest has been a major point of interest. Perhaps it was an oath?

Nigel Spivey claims that the stance indicates the figure reaching out in supplication, as shown by her oversized hand. The truth behind the meaning of her position remains unknown. The figure is sculpted with a tubular-like dress that does not display her knees or legs but is suggestive. The figure also has large feet at the bottom of the dress and a narrow waist defined by a wide belt.

It has also been speculated that the figure wore a cape instead of a robe and this was thought to be an epiblema. Originally executed in polychrome colors, a classical feature of many early Greek sculptures, the Lady of Auxerre presents small traces of red paint on her chest with a lower section of her robe showing delicate decorative work such as tiny squares within squares. Her accessories were originally painted to represent gold or bronze, which paralleled archaeological finds of the time.

Ancient Greece provided many wonderfully sculpted statues to draw inspiration from and provide insight into the culture of the antiquity era. Other famous Greek statues include The Parthenon Marbles (447 – 438 BC), The Charioteer of Delphi (470 BC), Zeus and Ganymede (470 BC), Kritios Boy (480 BC), The Dying Warrior (480 BC), Moschophoros (570 BC), Kleobis and Biton (580 BC), and Dipylon Kouros (600 BC).

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Most Famous Greek Statue?

The most famous Greek statue is considered to be the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory of Samothrace (295 – 290 BCE), displayed in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

What Is the Oldest Dated Greek Statue?

The oldest Greek statue is identified as the Lefkandi Centaur, which dates back to 920 BC.

Who Are the Most Famous Greek Sculptors?

The most famous Greek sculptors are considered to be Phidias, Myros, Praxiteles, Polyclitus, Lysippus, and Scopas.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Famous Greek Statues – Learn All About Ancient Greek Artifacts.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 10, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/famous-greek-statues/

Anthony, J. (2022, 10 October). Famous Greek Statues – Learn All About Ancient Greek Artifacts. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/famous-greek-statues/

Anthony, Jordan. “Famous Greek Statues – Learn All About Ancient Greek Artifacts.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 10, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/famous-greek-statues/.