Memento Mori Art – Exploring How Artists Interpret Death

Death is universal. Thankfully, there is an entire art form devoted to reminding us of just that. Memento Mori artists recognized that along with birth, death is a destiny that binds people together. Appearing in art across history and disciplines, death in art has transcended the boundaries of space and time.

The Macabre Meaning of Memento Mori Art

Death is universal. Thankfully there is an entire art form devoted to reminding us of just that. Memento Mori artists recognized that along with birth, death is a destiny that binds people together. Appearing in art across history and disciplines, death in art has transcended the boundaries of space and time.

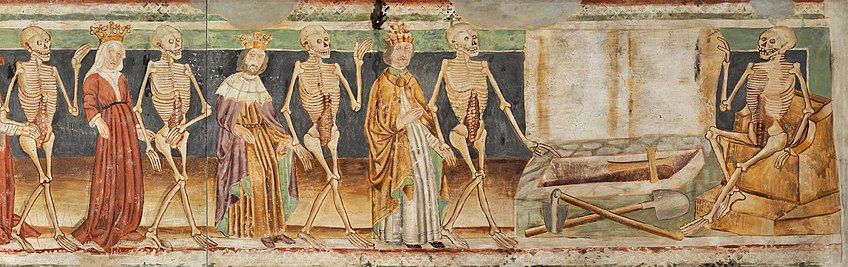

Dance of Death (1490) by Janez iz Kastva; National Gallery of Slovenia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dance of Death (1490) by Janez iz Kastva; National Gallery of Slovenia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

European Memento Mori paintings first emerged in the dark ages and continued far into Modern art. Therefore, Memento Mori is a broad term, but it has distinctions, tropes, and subcategories that help us analyze various forms through which it tends to manifest.

Today, Memento Mori symbols have become a central component of visual culture and can range from odd and gruesome to comical, or seductive.

What Is Memento Mori?

The Latin phrase ‘Memento Mori’ means ‘Remember, you must die. In art history, Memento Mori often refers to images or implications of death in art. Founded on the tenets of repentance in the Christian religion, Memento mori was a macabre yet powerful tool to remind viewers to improve their ways so that they can be saved in the afterlife.

Memento Mori Background

While macabre imagery predates it, late medieval and early modern artists’ fascination with the macabre is considered a byproduct of the global plague pandemic that swept across Europe in the mid-14th century. An example of this predation is The Three Living, And the Three Dead, From The De Lisle Psalter (ca. 1308 – 1340) clearly drawn from the macabre but created in England a few years prior to the plague outbreak. Nonetheless, the Memento Mori category and terminology first emerged during the late Middle Ages when the recurring bubonic plague, otherwise known as the Black Death, was an ever-present threat. From the 1340s onward, the plague dissipated entire families, towns, and countries.

People witnessed death up close, often dying in their own homes, and preparing their own dead for burial. Due to the lack of medicine, life expectancy was shorter.

This caused Memento mori artists and artisans to produce paintings, sculptures, architecture, other objects, poetry, and even music that engaged with the idea of remembering one’s death. These objects contributed to a rich tradition of Memento Mori in the early art of Europe, emphasizing the simple fact that no matter who we are, eventually death will come to us all. While death was more common then, these artists sensed a need for more reminders. To us, this macabre art form may come off as a threat, seemingly invoking terror in any potential wrongdoer. But because our medieval counterparts had become more familiar with death, these reminders of mortality were likely received in more neutral ways. As gentle reminders of the sad fact that the mortal experience was fleeting, but that death was also a joyful passage to God.

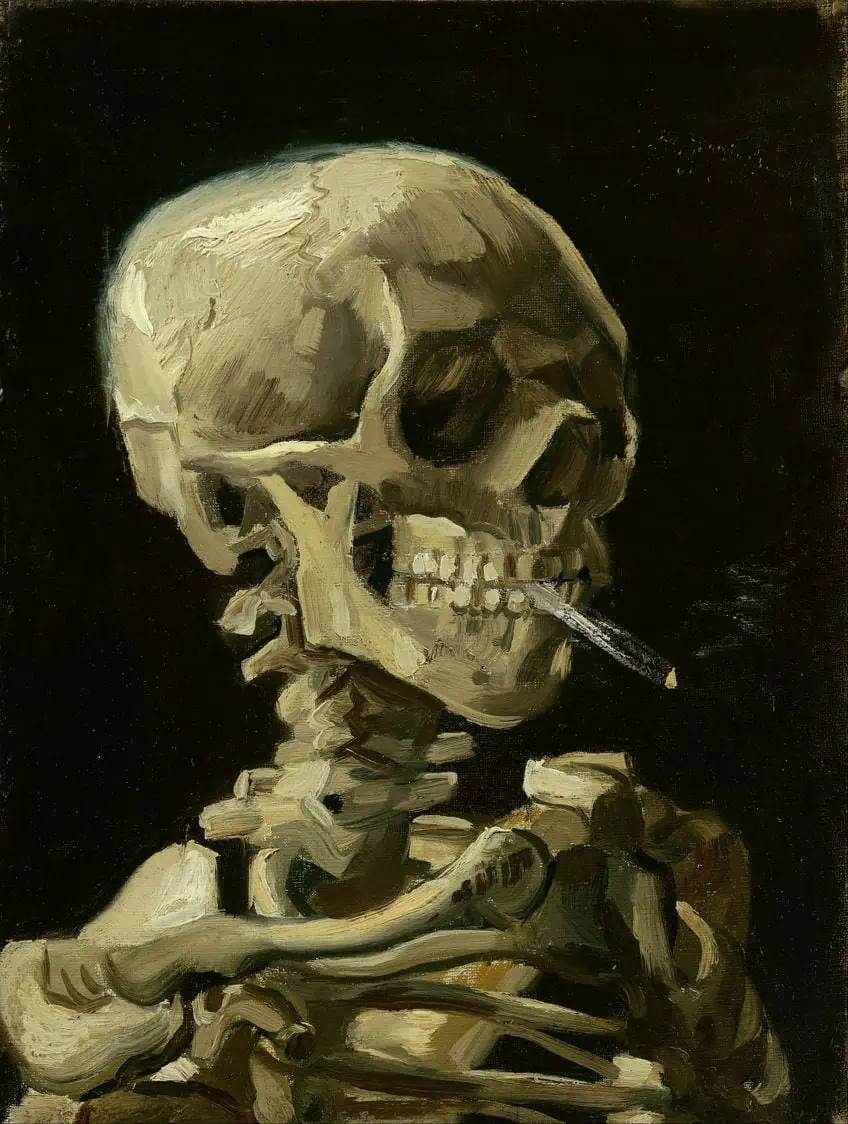

Skulls and Skeletons

Skull paintings were the key symbol of Memento Mori objects in the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Modern art periods. Most Dance Macabre images feature dancing skeletons, and most Vanitas paintings feature a skull. Skulls became popular symbols of Memento Mori art because they were a convenient reminder that life and the mortal world are fleeting. While those living are identifiable through facial features, skulls and skeletons are not and they can therefore represent and relate to any viewer. Skulls were common in paintings, but they also made popular three-dimensional objects. Real or carved skulls were kept to cultivate a detachment from earthly goods and pleasures, which would eventually be replaced by eternal life, be it in heaven or hell.

Memento Mori also appears in the buildings of many saints and hermits in the history of the Christian church. Scattered through Europe are examples of the chapel of bones or cadaver tombs, where surfaces are covered with human bones.

The Capuchin Crypt in Italy, Sedlec Ossuary in Prague, and Capela dos Ossos in Portugal are decorated with the bones of the congregations, monks, friars, and priests who served them. The Capela dos Ossos brandishes a text that reads: “We bones, lying here bare, await yours.” Many cadaver tombs feature images of the deceased in life, and after their death, sculptures of rotting flesh and decayed human corpses, usually accompanied by a Latin inscription that reads: “Hodie mihi, cras tibi”, meaning “what I am, soon you shall be.” It was through the painted skull that viewers first had a new kind of access to the hidden structures beneath the body’s external appearances, appealing to those with a curiosity for scientific analysis. The virtuosity of Memento Mori artists provided viewers with lessons in human anatomy without veering on the diagrammatic.

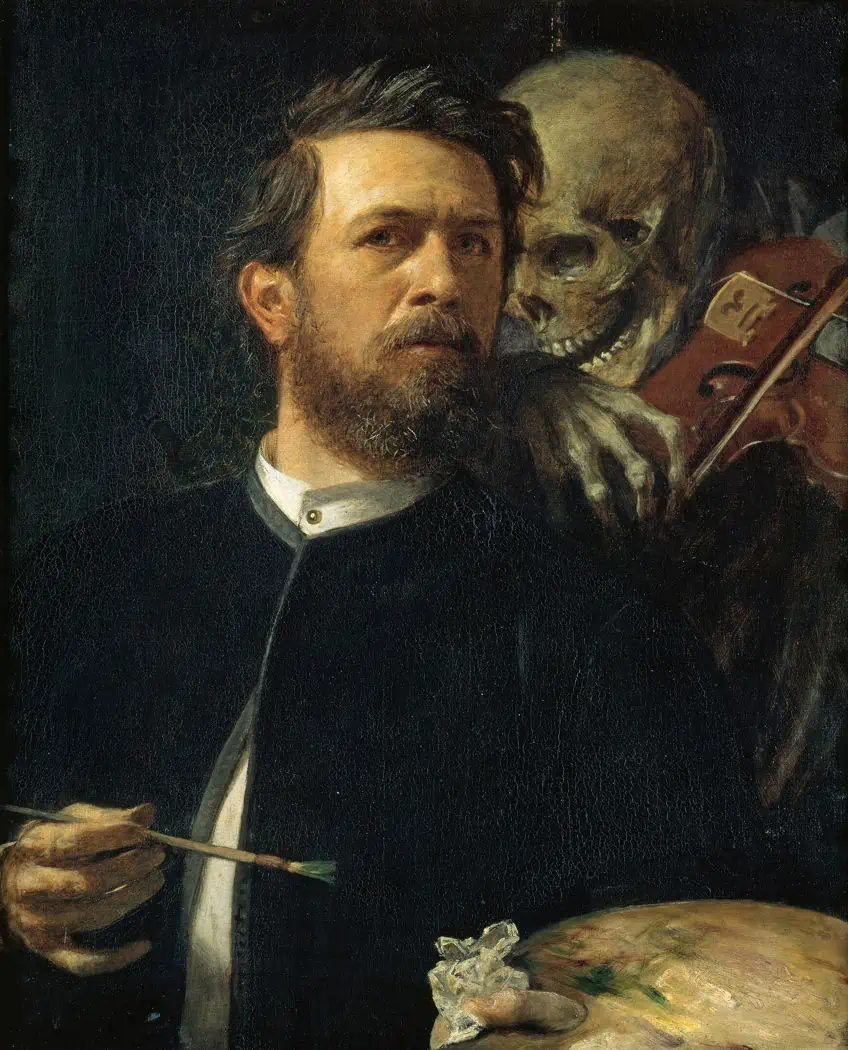

Dance Macabre

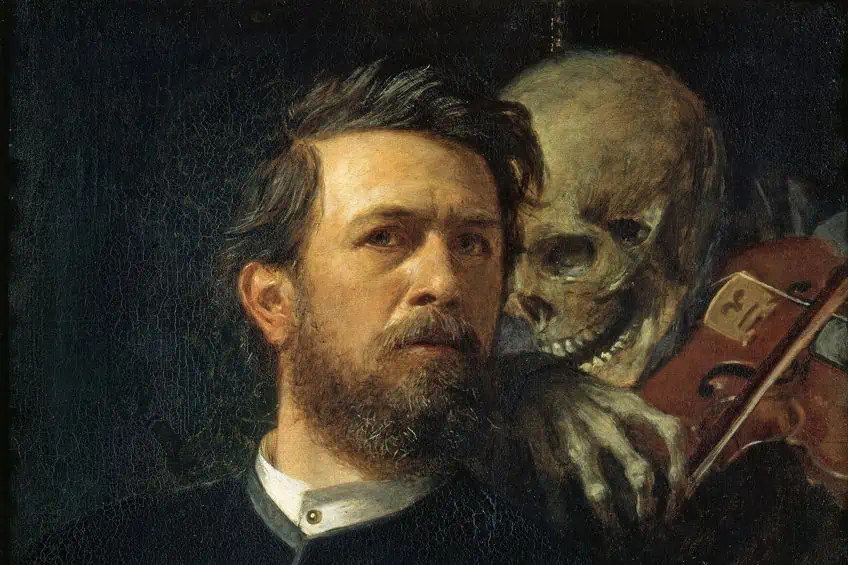

Dance Macabre (or the Dance of Death) is a trope of Memento Mori art that emerged in the late Middle Ages. It often portrays skeletons, usually both skeletons and the living, mostly with a musical instrument, engaged in a dance. During the dance, the skeletons can be seen guiding the living towards the grave. Dance Macabre frequently features figures from various walks of life, social class, and age groups. Men, women, babies, children, the elderly, merchants, laborers, clergy, nobles, and royals were placed alongside one another as they made their way through the steps of the dance.

The Dance Macabre reminds the viewer that earthly conditions of rank, privilege, and hierarchy will be stripped away on judgment day and that death is the ultimate leveler.

It’s important to note that Dance Macabre which is part of the Memento Mori tradition initially prominent in the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance period was essentially Christian art. The development of these representational interests and techniques worked in tandem with major mortality events which sparked an interest in the afterlife and the macabre.

Hans Holbein the Younger’s Effective Mastery of Death in Art

In 1538, while living in Basel, Hans Holbein the Younger was commissioned by Melchior and Gaspard Trechsel. The brothers operated a publishing house in Lyon, a city in the east of France. Their book Les Simulachres & Historiees Faces De La Mort was the commission Hans Holbein was responding to when he created the series known today as Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death. In collaboration with the block carver Hans Luselburger, Holbein initially designed his series of images in the 1520s and produced it in 1533.

The Trechsels finally published the volume in 1538, adding to Holbein’s images some texts, including a preface, poetry, tracts on mortality, and quotes from the bible. The book included other elements of visual imagery, but it was Holbein’s designs that made the impact. In the 1538 edition, Holbein’s Dance of Death posits images as mirrors, drawing from the prominent late Medieval trope akin to what we might today call the self-help genre. Holbein’s Dance of Death encouraged meditations on mortality. It saw itself as a mirror of conduct and referenced numerous sources. The title page of the first printed version of the Dance of Death introduced the book as the “Mirror of salvation for all people of all classes”.

The Ambassadors (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger

| Artist | Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497 – 1543) |

| Date | 1533 |

| Medium | Oil on oak |

| Dimensions (cm) | 207 x 209.5 |

| Location | National Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

Arguably the most famous skull painting in art history is the anamorphic one in The Ambassadors (1533). With this iconic painting, Hans Holbein the Younger literally stretched Memento Mori to its limits. The Ambassadors is symbolically rich, depicting two powerful men, the French ambassador Jean de Dinteville on the left and the Bishop of Lavaur Georges de Selve on the right. Behind them is a luxurious green damask curtain, and on the table, an expensive Turkish carpet. We see musical Instruments as well as instruments that map the earth and the stars.

Disrupting the pristine picture of these two splendidly dressed men and their earthly delights is a floating object which looks gray in color and had previously been assumed to be depicting a cuttlefish bone.

But it turns out that the strange object in the foreground, between the feet of the ambassadors, is a large, distorted skull. Holbein requires the viewer to seek out the perspective to properly recognize this hidden reminder of mortality. Specifically, the viewer must move to view it from the bottom right corner for the image to appear as a clear depiction of a skull. On one hand, the skull could be experienced as the artist’s response to the sitters’ vanity, and this would not have been uncommon for much of the portraiture of the time. On the other hand, Holbein’s hidden reminder of the frailty of life was a symbol of hope and salvation for pious Christians at a time of prosperity and greed.

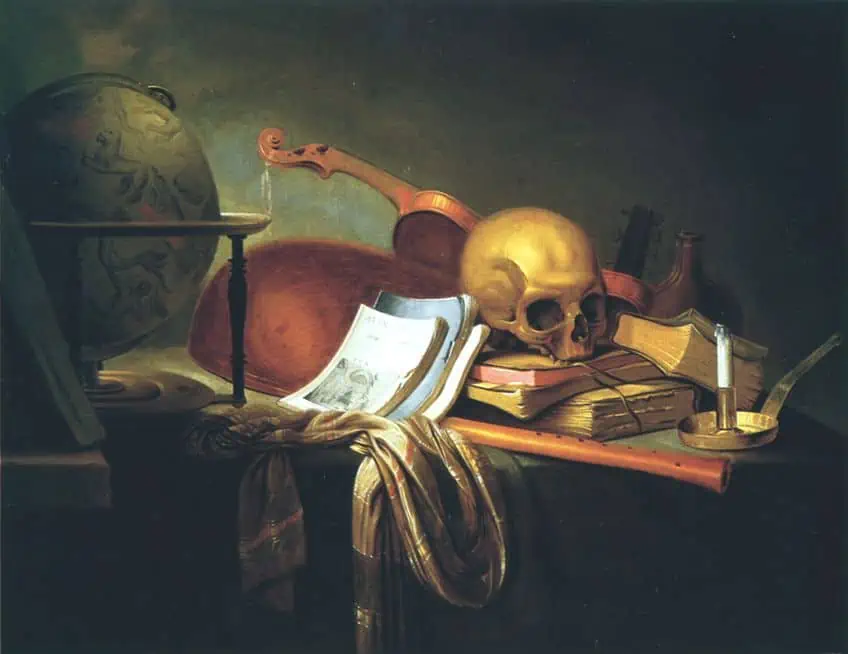

Vanitas Paintings

Vanitas is the Latin word for vanity. The origin of this Memento Mori painting genre is in the Latin translation of the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes in the bible. The book translates the Hebrew word for breath as vanitas and reads “vanity of vanities, all is vanity”. The popularity of Vanitas paintings which are acknowledged as Memento Mori objects was influenced by the rise of Calvinism in the Netherlands. Christianity was the dominant religion at the time in Europe. It had various branches such as Protestantism, which had its own branches such as Calvinism. Vanitas paintings fall under a subgenre of realistic still-life paintings with these religious connotations. The Vanitas style emerged in the Netherlands in the early 17th century during what we call the Dutch Golden Age (1581 – 1672). The movement was popularized by its moral approach to the growing prosperity of 17th-century Holland.

Some of the most well-known 17th-century Dutch Vanitas painters include Pieter Steenwijck, Harmen Steenwijck, and Willem Claesz Heda.

Earlier Dutch still-life trends like Asbankstillijven and later Ontbijt paintings contributed to the evolution of Vanitas paintings. Asbankstillijven which translates to ‘ostentatious paintings’ were the opposite of Vanitas paintings as they were painted purely for pleasure, mostly depicting luxurious items and banquets of food. Ontbijt paintings which translate to ‘breakfast paintings’ were similar, but more like Vanitas paintings, in that, they served as warnings against indulgence and gluttony. The Vanitas artistic trope that emerged during the Dutch Golden Age produced artworks that often-included depictions of several symbolic objects. These objects were intended to highlight that earthly goods and pleasures were temporary and therefore worthless as they could not be brought to the afterlife.

These paintings were extremely popular with the Dutch who enjoyed them at all class levels. Rather than display them in churches or public spaces, middle-class people decorated their private homes with them. While professional Vanitas paintings with incredible realism of custom objects were reserved for the upper echelons of society, the lower classes could afford amateur street art or prints which copied the popular trends and could cost only a few coins.

In an era before photography, these painters achieved incredibly realistic results through oil-based paint and lots of practice. Oil pigment was notoriously difficult to master, hard to clean, expensive, and even poisonous. This made Vanitas paintings even more lucrative. Of course, the high cost of Vanitas paintings presents a paradox to the meaning they intend to convey. Nonetheless, Vanitas paintings spread from the Netherlands to the rest of the world and became emblems of the Renaissance period and beyond.

The Symbolism of Vanitas Paintings

The evolution from simple still-life paintings to more articulate skull still-life paintings including other symbols of death helps us understand the symbolism of Vanitas paintings. They are filled with recurrent and sometimes hidden symbols whose dissection requires a level of negotiation. The sheer volume of objects piled into these paintings is the first sign which points to the multitude of distractions in life. Elements that painters included in Vanitas paintings were mainly objects, though figures made appearances, especially in later years. The intimate compositions were often dimly lit, and the objects were usually arranged to reflect the organization of interior, domestic scenes.

The aim of the calm, formal arrangement of these interior compositions was to portray death as domestic and ordinary.

The Netherlands is well known for its tulips, so it is no wonder that flowers were a prominent feature of Vanitas paintings. They are often depicted as either wilting or about to wilt, symbolizing the ephemerality of beauty. Different types of flowers carried specific meanings. Daisies represent purity, carnations were romantic, and tulips stood for nobility. Fruits also made frequent appearances in Vanitas paintings. Apples connoted the original sin of Adam and Eve, while pears suggested marital faithfulness, pomegranates – resurrection, and lemons could either represent bitterness and deception or encourage moderation as lemon water was used to dilute alcohol. Often fruit was depicted as rotting, which referred to life’s temporality and fragility.

Seafood and meat often symbolized luxury and indulgence in life’s pleasures. Lobsters represented gluttony while oysters stood for lust. Bugs like ants, flies, and maggots symbolized death and destruction. Caterpillars and butterflies were associated with rebirth or change. As bees sacrifice themselves for the hive, they were seen as sacrificial. Because of Thor’s connection to stag beetles in European mythology, beetles signified salvation and immortality. Vanitas paintings also included symbols of the arts and sciences, such as books and maps,

which can be a confusing symbol of death for the modern viewer. By the 1600s, books had become more common, owing to the invention of the Gutenberg Printing Press in 1440. They had played an important role in the spreading of the Protestant religion in Europe, from which Vanitas paintings had emerged. However, as they were still expensive luxury items at the time, Vanitas paintings used them to symbolize the arrogance and brevity of knowledge.

Elements like coins, purses, paper, seashells, jewelry, and gold, were considered luxury items that displayed wealth and power.

As such, Vanitas paintings represented greed. Musical instruments such as flutes and loots recalled an ancient Greek kind of promiscuity and therefore expressed indulgence and pleasure. As people do not usually leave their objects lying around like this, scattered decks of playing cards, half-smoked pipes, tobacco, and upended or empty goblets of wine referenced addiction and the loss of pleasure. Reflective surfaces promoted the practice of self-reflection. Candles, clocks, and hourglasses were a symbol of the passing of time. The globe or floating bubble was another popular symbol of Vanitas paintings included to indicate vanity, evoke the fleeting nature of life, as well as resurrection and eternal life.

Of course, the most iconic and popular symbol of Vanitas paintings was the human skull. Vanitas paintings might as well be called skull paintings. In traditional still life Vanitas paintings, skulls, skeletons, or grim reaper characters are the dominant subject, often seen at the center of a Vanitas composition. These symbols are a reminder of the mortality of the viewer. The fact that they too will one day rot and become skeletons.

Memento Mori Art in Modern and Contemporary Art

While the term Memento Mori seemed to have peaked in Victorian England, Modern artists continue to be inspired by the traditional theme of death in art. With their own famous paintings of death, modern artists like Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso appeared apt to amplify the twofold nature of Memento Mori’s mission, which is to ensure that we remember death but that we also remember not to fear it. Contemporary artists have followed suit.

Audrey Flack: Marilyn (1977)

| Artist | Audrey Flack (1931 – Present) |

| Date | 1977 |

| Medium | Oil over acrylic on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 243.8 x 243.8 |

| Location | University of Arizona Museum of Art, Arizona, United States |

Marilyn Monroe was a well-known film and fashion icon from the 1950s and 60s Hollywood Era. She had already been famously immortalized in one of Andy Warhol’s artworks. The influence of 17th-century Dutch Vanitas painting is clear through Audrey Flack’s inclusion of traditional Vanitas objects like the hourglass and the fleeting candle in her painting Marilyn (1977) which operates as a commemoration of the life and death of the celebrity.

Flack’s densely packed, hyperrealist assemblage painting Marilyn proudly proclaims the decade that had passed since the icon’s 1963 death.

But Flack also incorporates modern elements into the Vanitas lexicon. Lipstick, perfumes, mirrors, a photograph, and a calendar – are all extremely well-rendered objects with textures and colors reflecting Flack’s own contemporary context. As a result, this painting’s palette is brighter and the mood more upbeat than a typical Vanitas. Through the inclusion of personal objects, this artist explores the passage of her own time, in her life whilst simultaneously commemorating the life and death of Marilyn Monroe. Flack produced an entire Vanitas Series featuring common Memento Mori symbols from classic Vanitas images, but her skull still-life paintings included modern emblems of human vanity such as make-up and dice.

Damien Hirst: For the Love of God (2007)

| Artist | Damien Hirst (1965 – Present) |

| Date | 2007 |

| Medium | Platinum cast of a human skull, encrusted with diamonds |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unknown |

| Location | White Cube Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

In 2007, British artist Damien Hirst produced one of the most iconic modern-day examples of Memento Mori art. Hirst’s For the Love of God (2007) was marketed as the most expensive contemporary artwork in the world, and it sold for $100 million that same year, arguably capitalizing on the fanatic commodification of death in art. Hirst’s sculpture For the Love of God is a platinum cast replica of a 13th-century skull belonging to a 35-year-old man. The skull is entirely encrusted with 8601 flawless diamonds and flaunts real human teeth.

While it may be the most expensive, For the Love of God is not the first Hirst artwork to feature Memento Mori symbols like skulls, butterflies, and decaying objects.

Hirst makes intriguing variations in his interpretations. In contrast to traditional Memento Mori, Vanitas, or other examples of death in art which tend to fill their compositions with dim light, the reflection of light on the diamonds in For the Love of God makes Hirst’s sculpture startlingly luminous. Hirst also deviates from the moral implications of Memento Mori. The artist seems to poke fun at earlier depictions of death, suggesting that fate could be avoided through medical intervention. While it lands its punchline, For the Love of God is boldly obnoxious and sinister and has widely been criticized for its tastelessness.

Memento Mori in Popular Culture

Examples of Memento Mori cultural traditions can be found all around the world. Skull imagery can be seen throughout Mexican culture, and their festival Day of the Dead is world famous for its annual commemoration of death. The Buddhists have sand mandalas and Japanese Zen culture expresses Memento Mori values through Japanese death poems. These cultural phenomena perform the same function which is to point us towards the inevitability of death.

Comic books, such as Grim Reaper in Thrilling Comics #1 (1939) and Grim Reaper in Wonder Comics #1 (1944), reveal the popular attempt to make death ubiquitous.

Death in comic books juxtaposes death as a supervillain that we fear with death the superhero that we love. The African American musical sensation, The Weeknd, has a radio show called Memento Mori. In his last music video leading up to his death, Mac Miller is seen carving the words “Memento Mori”’ onto the inner surface of his own coffin. Skull imagery has become hugely commodified and can be seen on mainstream clothing, accessories, digital devices, and other material goods.

The End Is Nigh

As Memento Mori appears across different decades and disciplines, its parameters are endless. These artworks have not been limited to the Medieval-Renaissance period but appear whenever there are cultures that have some religious component. Within any system of morality, artistic representations have sought to come to terms with death. This is one of the reasons Memento Mori remains so important today.

Initially, Memento Mori sought to remind viewers that the measure of their worth should be based on the attentive preservation of their immortal souls. Instead of prioritizing their worldly possessions and social status, they were to prepare themselves for eternal life by striving for virtue. People who repented and sought forgiveness for their sins could secure salvation for their souls in time for the afterlife that awaited them, where divine judgment would determine whether they went to heaven or hell. In the past, death was a fundamental part of day-to-day experiences. Because of the distance offered by technological advancements and medical breakthroughs, the symbolic engagement with death is often overlooked in the modern world. Despite this, death prevails. The fundamental fact remains that someday each of us must die.

Memento Mori may come off as a fetishization of death. The moral instruction of famous paintings of death can appear superficially to either accept or mitigate the difficulty of death. More meaningfully though, Memento Mori art can be an earnest reminder that death is certain. That proximity to it even in life can be beneficial.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does Memento Mori Use Real Dead Bodies?

Yes, it does. For example, Sally Man’s Body Farm (2000) is a gut-wrenching series of photographs featuring cadavers that have been donated to police agencies to train officers and cadaver dogs. The bodies are decomposed and left around for the cadaver dogs to find as part of their training.

Why Do Vanitas Paintings Have Snails?

Strangely, snails often made an appearance in Vanitas paintings. They were meant to represent the Judeo-Christian icon, the Virgin Mary, due to the widespread misconception that snails were asexual, and therefore technically virgins.

Is Memento Mori Art Just Another Word for Funeral Art?

Considering that much of the known Egyptian art and artifacts, including burial masks, are found in tombs and other places of the dead, it makes sense that Memento Mori art also appears to be funeral related. The death of others has often been fertile ground for Memento Mori artists.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Memento Mori Art – Exploring How Artists Interpret Death.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 27, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/memento-mori-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 27 September). Memento Mori Art – Exploring How Artists Interpret Death. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/memento-mori-art/

Davis, Liam. “Memento Mori Art – Exploring How Artists Interpret Death.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 27, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/memento-mori-art/.

Thank you for this article. I was searching for something on memento mori for Easter contemplation and this article is very enlightening.

Thank you Peter for your kind feedback.