Mesopotamian Art and Architecture – The Art of Mesopotamia

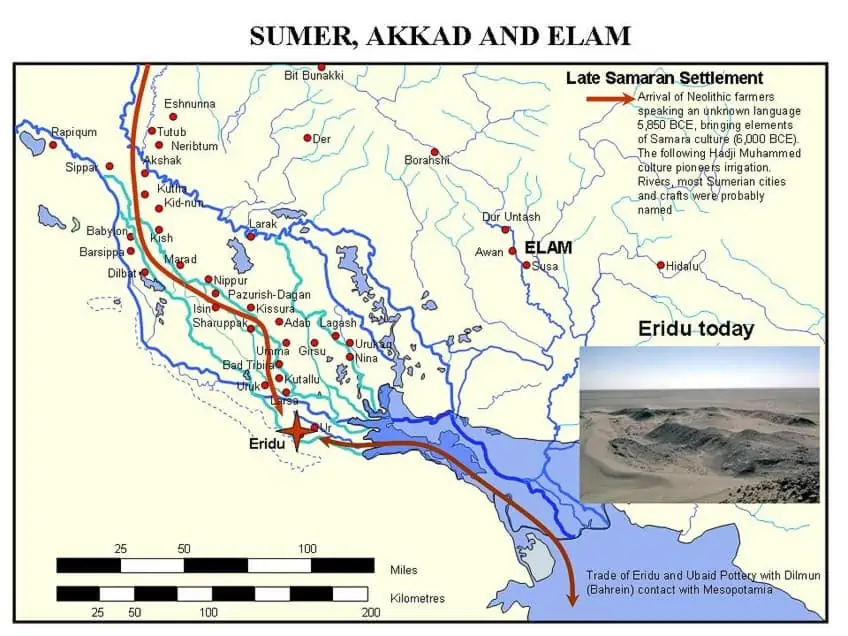

The world’s earliest urban civilization, Mesopotamia, is an area in Western Asia in the Tigris-Euphrates River system. It is rich in history and was home to a developed cultural realm that included music, art, and literature. Lower Mesopotamian Sumerians formed the first towns, devised writing and poetry, and built magnificent architecture. The history of this civilization- which encompasses its social organization, military victories, the practice of religion, and natural surroundings- has profoundly impacted and connected to the artworks and buildings that originated from it. To comprehend the people who lived there and their workmanship better, we will be looking more closely at the art of Mesopotamia and its architecture.

Contents

A Brief Look into the Rich History of Mesopotamia

The word “Mesopotamia” comes from the Greek words mesos, which means “between”, and potamos, which means “river”. The name Mesopotamia is appropriate given the region in which it is found because it is situated in a location with fertile land between the Tigres and Euphrates Rivers. Kuwait, Modern-day Iraq, Turkey, and Syria are the current occupants of the Mesopotamian region. This civilization’s history has been substantially shaped by the succession of governing bodies that have changed over time.

During the Paleolithic era, the first humans began to make Mesopotamia their home and began to create Mesopotamia art.

People began to live in small settlements by 14,000 BC These settlements began the domestication of animals and developed their agriculture and soon became whole farming communities. All these developments took place within a period of five thousand years. They also created irrigation techniques that took advantage of the large space taken by the rivers.

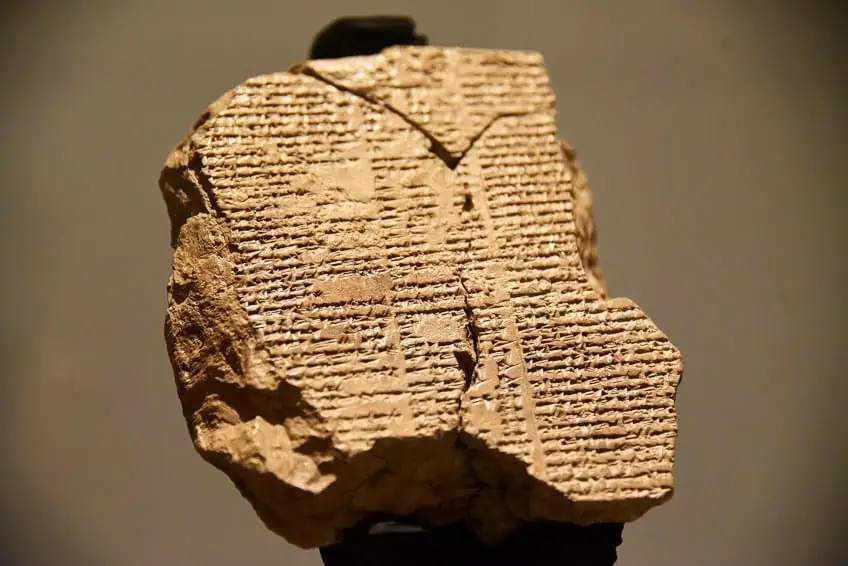

Soon these small settlements turned into large cities with the Sumer being one of the earliest examples. Around 3200 BC, Uruk was built and housed around 50,000 inhabitants. Uruk was rich in art and architecture and contained large amounts of public art, large columns, and temples. The Sumerian people took leadership over Mesopotamia under several city-states by the time of 3000 BC. Believed to be born around 2700 BC was one of many kings that ruled Mesopotamia, Gilgamesh. The poem The Epic of Gilgamesh (2100 – 1200 BC) is known as one of the earliest works of literature from ancient Mesopotamia.

Established under Sargon the Great, the Akkadian Empire was the first multicultural empire with a main government.

This empire was founded from 2234 to 2154 BC The first code of law was established under Ur-Namma when the Sumerians gained control again. Following the regain of control by the Sumerians was a wave of vanquishments and invasions with numerous different leaders taking hold of power at different times.

At approximately 1365 BC, the Assyrian Empire came to light and grew significantly throughout the next two centuries. In 626 BC, Babylonian public official Nabopolassar took hold of the throne despite many attempts at peace in the years prior. The Babylonian Empire that began in 614 BC was ruled by his son, Nebuchadnezzar. He was known for his decorative architecture, most notably known, as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Under Persian Rule, at approximately 550 BC, Mesopotamian culture ended.

Major Monuments in Mesopotamian Architecture

Architecture during this era was a challenge due to the location as it consisted of few reliable and usable materials, meaning materials like stone were scarce but clay was in abundance. Due to this, Mesopotamian architects preferred to make use of brick and adobe in their architectural foundations.

Temples

In the 2,500 years of Sumerian history, temples frequently predated the development of urban settlements and developed from modest one-room huts to grandiose multiacre complexes. Buttresses, recesses, and half columns were among the more sophisticated building elements used in Sumerian temples, castles, and palaces. Sumerian temples developed from older Ubaid temples chronologically. A new temple was constructed on top of the old one’s foundations as it degenerated. The succeeding temple was bigger and more complex than the earlier temple.

The temple’s function was to serve as the axis Mundi—a site where gods and humans might interact.

The temple’s layout was rectangular with corners that pointed in the four cardinal directions to represent the four rivers that flow from the mountain to the four hemispheres of the earth. The orientation also serves the more practical aim of allowing Sumerian timekeepers to use the temple roof as an observatory.

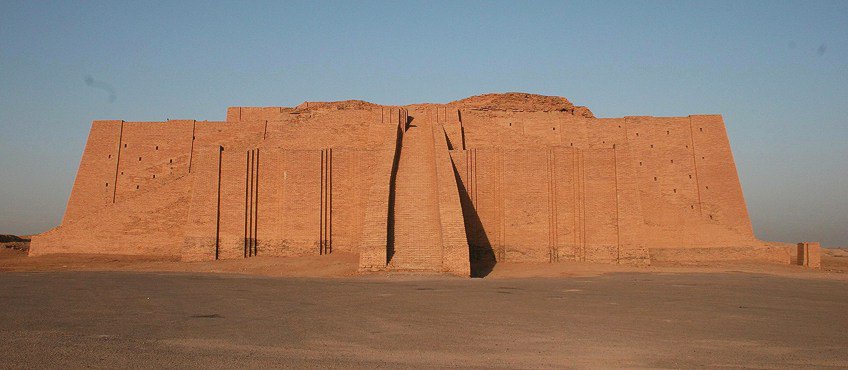

The entrance points for the gods and humans were the doors of the long and short axes, respectively. It was called the bent axis approach because everyone entering would swivel 90 degrees to face the statue at the end of the center hall. The Ziggurat, a square tower with several stepped levels and a shrine at its top, was the temple type’s most distinctive feature. It would be in the area of one of the courtyard’s smaller sides. Its sides would face the four compass bearings, and a ramp around its perimeter would ascend to various levels.

As an alternative, there were two symmetrical staircases that rose the front or sides and were constructed out of the most expensive materials, including marble, alabaster, lapis lazuli, gold, and cedar wood.

Ziggurats were places where Mesopotamians would worship their gods. Ziggurats were incredibly tall for them to reach up to the heavens where the gods were thought to live. The first Ziggurats were built in Ur, the capital city of Sumer, which was the first civilization. The Etemenanki Ziggurat was a huge pyramid temple located in Babylon and is estimated to have been 90m tall which is twice the height of the Statue of Liberty in New York City.

Palaces

During the Early Dynastic I era, the palace was built. As power is increasingly consolidated, the palace expands in size and sophistication from a very simple foundation. The early Mesopotamian nobles resided in large, frequently ornately decorated houses. The earliest instances are from locations in the Diyala River valley, like Khafajah and Tell Asmar. These palaces, which date to the third millennium BC, served as substantial socioeconomic institutions; as a result, in addition to housing residential and private functions, they also contained workshops for craftspeople, food storage facilities, and ceremonial courtyards, and are frequently linked with shrines.

Iron Age Assyrian palaces, particularly those at Kalhu/Nimrud, Dur Sharrukin/Khorsabad, and Ninuwa/Nineveh, have become famed for their relief carvings and extensive graphic and textual storytelling systems on their walls.

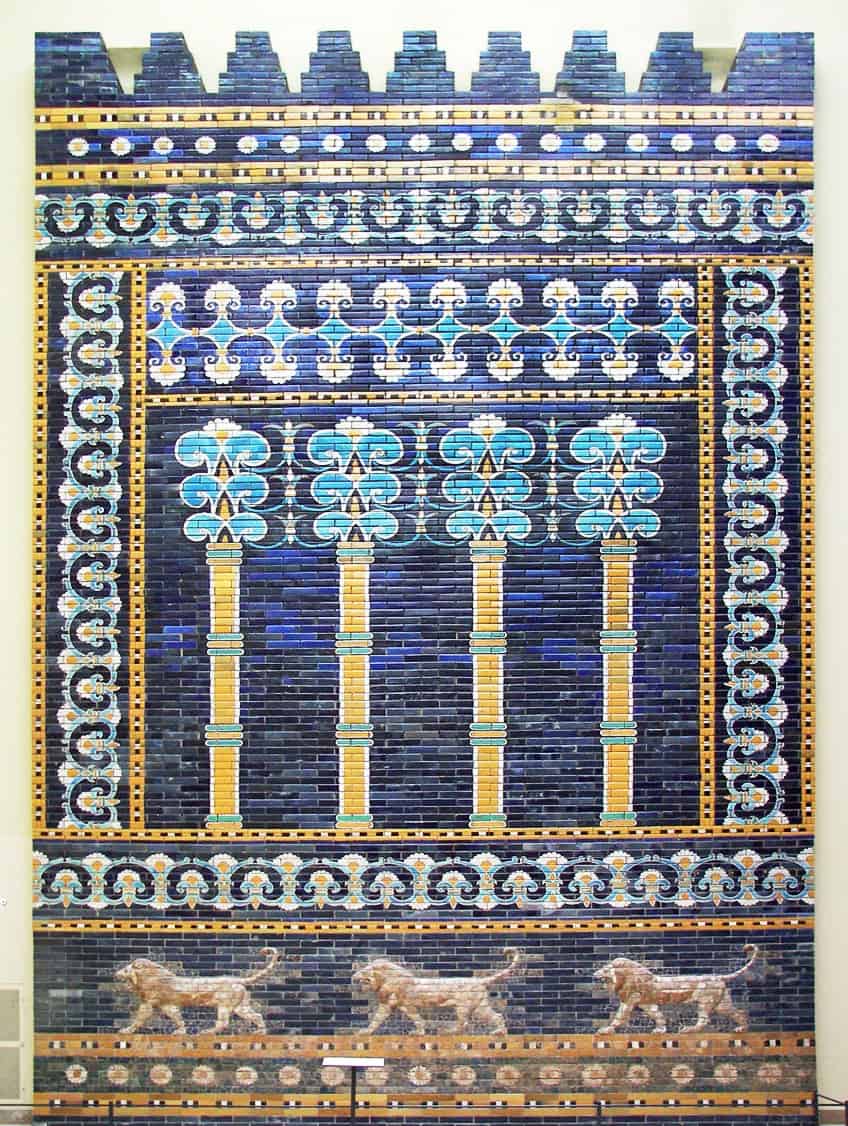

Palaces were a collection of prismatic structures of varying sizes connected by hallways, galleries, and corridors, with large courtyards positioned in the middle and encircled by walls. They were made up of straightforward pyramidal buildings with a central courtyard that served as their source of lighting and ventilation. Frescoes on lime plaster or vividly colored enameled brick linings and reliefs were used to embellish the interior walls.

Numerous ivory furniture pieces discovered in certain Assyrian palaces indicate that the Neo-Hittite rulers of North Syria had active trading contacts with Assyria at the time. The timber gates of important structures were ornamented with bronze repousse bands, but most of them were plundered with the fall of the empire; the Balawat Gates are the main survival.

Massive stone statues of winged genies, lamassu, and apotropaic mythological characters guarded gates and significant routes.

These Iron Age palaces’ structures were arranged around both substantial and intimate courtyards. The king’s throne room typically led out to a large ceremonial courtyard where significant state council meetings and formal rituals took place.

Nineveh was one of the most famous palaces that was located in the ancient Assyrian city of upper Mesopotamia. Due to its placement on the Kuyunjik mound of the Nineveh citadel, the name was appropriately given to it. The palace has still to this day not been completely uncovered with its layout not yet fully understood. Due to King Sennacherib’s inscriptions, it is believed to have been built between 701 and 694 BC.

The palace was nearly completely burned in 612 BC when the Babylonians attacked.

Walls

Mesopotamian cities were fortified with massive walls. These walls were vertical with right angles cut into them, and at regular intervals, square towers served as reinforcement. Passages were made through doors that were reinforced. Half-barrel vaults served as the passages to these portals, and on either side were positioned the typical guardian statues. The Sumerian city of Uruk has several walls that were built there frequently as a kind of defense.

These walls were credited to the legendary King Gilgamesh. Soon after Mesopotamia started to become urbanized, walls started to grow swiftly all over the city.

In addition to gates and watchtowers, these city walls would also have a ditch around their perimeter that could be filled with water. Nebuchadnezzar II erected three walls around Babylon that were a staggering 40 feet high, with a top that was so wide that chariots could race around. Some people contend that Nebuchadnezzar II’s Babylon’s Ishtar Gate is superior to each of the recognized Wonders of the Ancient World.

The splendor of the walls has been mentioned by numerous ancient writers.

Tombs

Their graves were simple hypogea with brick vaults and multiple rooms that were designated from the exterior by a little monument devoid of any artistic merit, so architecturally speaking they were not particularly interesting. There were several “Royal Tombs,” or tombs specifically devoted to royalty. These so-called “Royal Tombs” have vaulted roofs over subterranean stone chambers.

Even though the majority of these tombs had been looted, they nevertheless hold amazing riches from ancient Mesopotamia.

Most of the Mesopotamian cemeteries were straightforward, ground-dug pit graves. These royal graves were little rectangular vaulted apartments under the earth, made of brick or stone, and had a ramp leading down within. When the most opulent tomb in ancient Mesopotamia was discovered, the woman within was dressed in gold and beautiful stones. She was decorated completely in luxurious jewelry. Three more bodies, which were most likely her servants were placed in the tomb with her.

Houses

It was frequently up to the residents of early Mesopotamia to create their housing. These Mesopotamia buildings were most commonly created from wooden doors, mud bricks, and reeds. Houses were commonly load-bearing so windows were not placed within the structures leading to the only opening of the houses being the door.

There was an obvious division between public and private life in Sumerian culture. This meant that the interiors of very few homes could be visible in direct view from the street.

The houses came in a variety of different sizes and shapes depending on the size of the family and their social status; however, the layout of the houses was usually the same with it being divided up into a central large room and with smaller rooms built around it. It became a common practice during the Ubaid period to include courtyards in the designs of houses to create a natural air conditioner.

This practice is still commonly used today in modern Iraqi architecture.

Arches

Arches were a common structural system that was made of used in ancient Mesopotamian architecture. The use of arches is often accredited to the Romans; however, the arch was first used by the Mesopotamians. The more frequently used load-bearing walls were not strong enough to hold up the pressure of the structures, so an arch was used to absorb most of the pressure.

This allowed for the inclusion of larger openings such as windows to improve wind flow and sunlight.

As early as the seventh century BC, round arches were employed in Mesopotamian architecture. Examples of this can be seen in the entryways of palaces like Dur-Sharrukin, where they can be seen in the central portal as well as in windows to the left and right of the entrance.

The Ishtar Gate, which dates to 575 BC, is where you can find the most well-known example of the round arch in Babylonian architecture.

Ancient Mesopotamian Arts and Cultures

Sumer was an ancient civilization that’s artistic style went through numerous changes throughout the different periods in its history. The region which is now known as modern Iraq which was once known as Sumer existed during the Early Bronze Age. It is believed by modern historians that Sumer was first settled by people known as the Ubaidians as early as c. 4500 and 4000 BC despite there being a lack of historical records in the region which note that the region did not go further back than c. 2900 BC.

The Ubaidians were the first people to make use of draining marshes for agriculture as well as the first to develop trade and to discover industries including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery.

The city of Eridu which belonged to the Sumerians and at the time bordered the Persian Gulf is considered to be the world’s first city. In Eridu, three separate cultures came together as one. The nomadic Semitic-speaking pastoralists (who were farmers that raised livestock), the peasant Ubaidian farmers, and the fishermen. The large quantities of food that could be stored that was created by this group of people would allow for the population of the region to create a land in which they could stay instead of their habits of migrating as hunter-gatherers.

This also allowed the population to grow, which would need a multi-sectioned labor force and a large quantity of labor sectioned into many different specialized arts and crafts. Established during the early Sumerian period an early type of wedge-shaped writing was called cuneiform.

Cuneiform and pictograms during this early period in time allow us to understand that there was a large use of pottery and other ancient Mesopotamian arts and traditions.

Clay was often used to make tablets that could be used for writing documents. During the early Sumerian period, another material that was made of great use was metal, which could be used for a variety of purposes. A type of casting used by smiths was made of use to create things such as blades for knives or a softer metal would be used such as copper and gold and could be hammered into things such as plates, necklaces, and collars. Many ancient Mesopotamian artifacts and Mesopotamia drawings were created from these cultures.

The Ubaid Period (c. 5500 – 3900 BC)

The Ubaid period consisted of many unique works of art which are most notably clay sculptures and figurines that were created by hand. These figurines were almost always naked figures of females that were delicately made with fine detail on the finished product. The bodies appear to follow certain standards, as evidenced by the shoulders’ pronounced angularity.

The figures created were quite realistic but simple in the way of geometric simplification of shapes and large eyes.

Another example of art from this period is distinctive in the painting technique applied to pottery, such as bowels or vases. The patterns were created in zig-zag and circular forms and were created by the use of a slow wheel in a domestic capacity.

This style of decoration would become popular throughout the region.

The Uruk Period (c. 4000 – 3100 BC)

The transition of periods from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period shifted the focus from the use of slow domestic wheels to works that were created on a much larger scale on wheels that would move faster and were created by specialized artists and were not painted. During the time of the region’s economic expansion, brand-new cities started to sprout up along the lucrative trade routes of the rivers and canals. Each of these cities had its government, which would hire individuals to fill specialized positions.

Mesopotamian artifacts from the Uruk era had been found across a wide area of territory, from Central Iran to the Mediterranean Sea and the Taurus Mountains of Turkey.

The Uruk culture had a tremendous impact on the area because Sumerian traders spread it. These traders eventually started to create their own cultures and economies to rival that of the Sumerians. Cities at this time were primarily theocratic, which means that people thought a god oversaw all of society and that a priest served as god’s emissary for earthly concerns. These divine monarchs would also request aid from an assembly of male and female elders.

This political framework would subsequently have an impact on the later Sumerian pantheon of gods.

There were no soldiers or organized acts of aggression during this period, which indicated that there was no need for city defense walls. When Uruk’s population reached over 50,000, it was immediately regarded as the world’s most advanced city at the time.

Types of Artisans and Craftsmen in Ancient Mesopotamia

The culture of the Mesopotamian people in Ancient Mesopotamia was significantly influenced by artisans. They created daily necessities like clothing, pots, baskets, canoes, and weapons. They also produced Mesopotamia art to exalt the ruler and the gods.

Potters

Clay was the most common material used for art in Mesopotamia. Clay had multiple different uses for creations such as pottery, monumental buildings, and tablets that were used to record history and legends. Throughout thousands of years, the Mesopotamians enhanced their skills in pottery.

The first use of pottery was created by hand to make things such as simple pots.

Later, they made use of the potter’s wheel which allowed for more detailed designs. Ovens that were burned at high temperatures were used to harden the clay. They learned how to use glazes and create different patterns and shapes in the pottery. The pottery soon became a work of art.

Jewelers

Specially made jewelry out of luxurious materials was a symbol of status and wealth in Ancient Mesopotamia. These pieces of jewelry were worn both by men and women. Jewelers made use of rare gemstones, silver, and gold in their art pieces to create intricate designs.

They produced a wide range of jewelry, such as bracelets, earrings, and necklaces.

Metalsmiths

The metalworkers of ancient Mesopotamia had learned to make bronze by mixing tin and copper by the time of 3000 BC. The metal would be melted at extremely high temperatures and then poured into molds to create all sorts of items.

These included weapons and sculptures.

Carpenters

Art of Mesopotamia included carpenters that were skilled artisans who produced many of the most significant objects out of imported wood, such as cedar from Lebanon. They used cedar to construct the kings’ palaces. Additionally, they built ships to sail the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and chariots for use in battle. Inlays were used to embellish many exquisite wooden objects.

They would use tiny bits of metal, glass, shell, and jewel to create stunning, gleaming ornaments for things like musical instruments, furniture, and sacred objects.

Stone Masons

Stonemasons sculpted some of the best extant examples of Mesopotamian art and skill. Everything from huge sculptures to minutely detailed reliefs was carved by them. The majority of the sculptures represented religious or historical symbols. They typically depicted gods or rulers. They also carved seals out of tiny, intricate cylinder stones.

Because they were employed as signatures, these seals were quite little. They could not be simply replicated since they were quite intricate.

Ceramics in Mesopotamian Art

A significant component of the ancient Mesopotamian arts, ceramics saw several changes in style and variety during the fourth millennium BC as a result of advances in the potter’s wheel. The manufacturing of ceramics began in East Asia between 20,000 and 10,000 BC, but the technique of using a potter’s wheel by throwing clay on it was a process that first appeared in Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium BC. Dated back to the Copper or Chalcolithic era is some of the oldest examples of clay vessels.

The Chalcolithic Era (c. 3500 – 2300 BC)

Between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age was the Chalcolithic, commonly referred to as the Copper Age. The Ubaid period saw the production of highly adorned pottery that was created at home on slow wheels. Mesopotamian painters created intricate and abstract paintings on burned clay jars, bowls, and vases, and their work is characterized by a regional aesthetic.

The development of the potter’s wheel allowed for the easier and more efficient production of ceramics throughout the ensuing age.

The Akkadian Empire (c. 2334 – 2154 BC)

Vases, jars, bowls, and many other ceramic items were still being made throughout the Akkadian occupation of Sumerian cities. Although some pieces feature abstract patterns and reliefs on them, they were generally unpainted.

The pieces were similar to the pottery from the Uruk era.

Ur III (c. 2112 – 2004 BC)

During the Third Ur Dynasty, unpainted ceramics with more intricate shapes like flowerpots, cake stands, and clay jars for storing liquids were still produced. Clay tablets were also created so that people could record information on them using reed-stylus-made styluses. The text may be baked in a kiln for prosperity if it was intended for archival purposes.

Tablets could also be used for daily administrative tasks including keeping track of employees, pets, wages, and other things.

Babylonian Ceramics

At this time, the employment of abstract patterns painted on pottery’s surface is once again fashionable, and the range of forms available for various uses—both practical and aesthetically pleasing—has greatly increased.

Abstract painting traces have been found on the clay exteriors of Mesopotamian objects from this time period, including pottery jars, vases, and goblets.

Architecture in Mesopotamia

Ancient structures from the Tigres-Euphrates River system, commonly known as Mesopotamia, make up the region’s architectural heritage. The land of Mesopotamia consists of several known cultures and spans a period from the 10th millennium BC to the 6th century BC, which was also when the first permanent sculptures were built.

Ziggurats, the courtyard house, and urban planning are among many Mesopotamian architectural achievements.

Mesopotamia had no profession for architecture, but some scribes planned and oversaw building projects for the state, nobility, or king. Based on archaeological evidence there are studies on ancient Mesopotamian architecture which consist of pictorial representations of the buildings and texts on the practices of the buildings.

The Uruk period’s primitive pictographs reveal that stone was scarce and that what there was had already been cut into blocks and seals. The most common building material was brick which was used to construct numerous types of buildings such as cities, temples, houses, and forts.

The city lay upon the artificial ground and had many towers. The houses in the city were also tower-like in appearance.

Studies of Mesopotamian architecture are primarily concerned with the design of palaces, temples, city walls, gateways, and other monumental structures. There is also some research on residential housing and architecture.

Building Materials

Round bricks were the most widely used type of construction material, but because they were relatively unsteady, Mesopotamian construction workers would place a column of bricks parallel to the rest every few rows. Bricks were hardened by placing them in the sun to bake.

Oven-baked bricks were much more durable than sunbaked bricks, so the buildings would eventually deteriorate due to the lack of durability in the bricks.

Buildings were often rebuilt in the same spot which would lead to slow raise in the level of the city. The leftover mounds of the structure are known as tells and can be found throughout the city. Civic structures used terracotta panels, colored stone cones, and clay nails hammered into the adobe brick to create a protective layer that ornamented the exterior to slow the degradation of the structure.

Some building materials that were specially priced were imported from places such as Lebanon, Arabia, and India. Some of the precious materials included cedar, diorite, and lapis lazuli.

Brick was used in the construction of Babylonian temples, which also had drains for rainwater collection and buttresses to sustain their massive constructions. The drains were constructed using lead. The early development of the pilaster and column was aided by the employment of brick, frescoes, and enameled tiles. The walls were frequently vividly colored and occasionally zinc- or gold-plated. The plaster also contained inset terracotta torches cones. Assyria copied Babylonian architecture, building its palaces and temples out of brick even though stone was the most frequent building material there.

Today, we have learned about Mesopotamian art, which dates back to the beginning of human civilization. We also talked extensively about Mesopotamian structures and architecture to gain insight into the way of life of the time. Since Mesopotamian art was primarily focused on the production of sculpture, ceramics, painting, and the building of Mesopotamian structures, no Mesopotamian drawings still exist today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Main Characteristics of Mesopotamian Art?

Mesopotamian artifacts, Mesopotamia drawings, and Mesopotamian sculptures were usually created for the use of religious practice and political uses. The most frequently used materials used by the Mesopotamians were clay, metal, and stone which would be created into reliefs and sculptures. The Uruk period was characterized by the growth of vivid narrative imagery and an increase in the realism of human figures.

What Was Babylonian Architecture and Its Greatest Achievement?

Mesopotamia buildings, specifically the large-scale Babylonian architecture, were well known. In addition to Etemenanki, they are credited with creating The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The Babylonian architecture was always great in size with immaculate detail.

What Is the Most Famous Piece of Ancient Mesopotamian Art?

The Code of Hammurabi, the first ever written law code, was the most significant work of art created during the Babylonian era (c. 1895 – 539 BC). This basalt stele has writing engraved and a relief sculpture cut into it.

Justin van Huyssteen is a writer, academic, and educator from Cape Town, South Africa. He holds a master’s degree in Theory of Literature. His primary focus in this field is the analysis of artistic objects through a number of theoretical lenses. His predominant theoretical areas of interest include narratology and critical theory in general, with a particular focus on animal studies. Other than academia, he is a novelist, game reviewer, and freelance writer. Justin’s preferred architectural movements include the more modern and postmodern types of architecture, such as Bauhaus, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Brutalist, and Futurist varieties like sustainable architecture. Justin is working for artfilemagazine as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and about us.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Mesopotamian Art and Architecture – The Art of Mesopotamia.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 19, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/mesopotamian-art-and-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 19 October). Mesopotamian Art and Architecture – The Art of Mesopotamia. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/mesopotamian-art-and-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Mesopotamian Art and Architecture – The Art of Mesopotamia.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 19, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/mesopotamian-art-and-architecture/.