Neo-Impressionism – History and Development of Divisionist Art

What is Neo-Impressionism art and what is the Neo-Impressionism definition? In the latter half of the 19th century, Neo-Impressionism artists abandoned the spontaneous nature and romance that many Impressionists praised, in favor of a new and rigorous approach to painting. The Neo-Impressionism artists strived to make more vivid paintings that reflected modern life by depending on the audience’s ability to optically mix the spots of color on the canvas. They aimed to represent people’s shifting interaction with the towns and countryside, as urban centers grew and technology advanced.

The History of Neo-Impressionism Art

The Neo-Impressionists looked to science to develop their artistic approach of contrasting diverse hues and tones to produce glistening, luminous surfaces in order to thoroughly depict the brilliance observed in nature. The artists aimed to enhance the visual sense of the image by carefully arranging opposing hues, as well as white, black, and gray, near to one another on the canvas. The Neo-Impressionism artists sought to create correspondences between emotional feelings and the lines, forms, and colors depicted on canvas, which spoke to the modernism of urban life in the industrialized period.

The Beginnings of Neo-Impressionism Art

By the mid-1880s, an innovative generation of creatives, who would later be more broadly referred to as Neo-Impressionism artists and included Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Vincent van Gogh, began developing novel techniques for color, line, and form because they believed that Impressionism’s emphasis on the light play was too constrained.

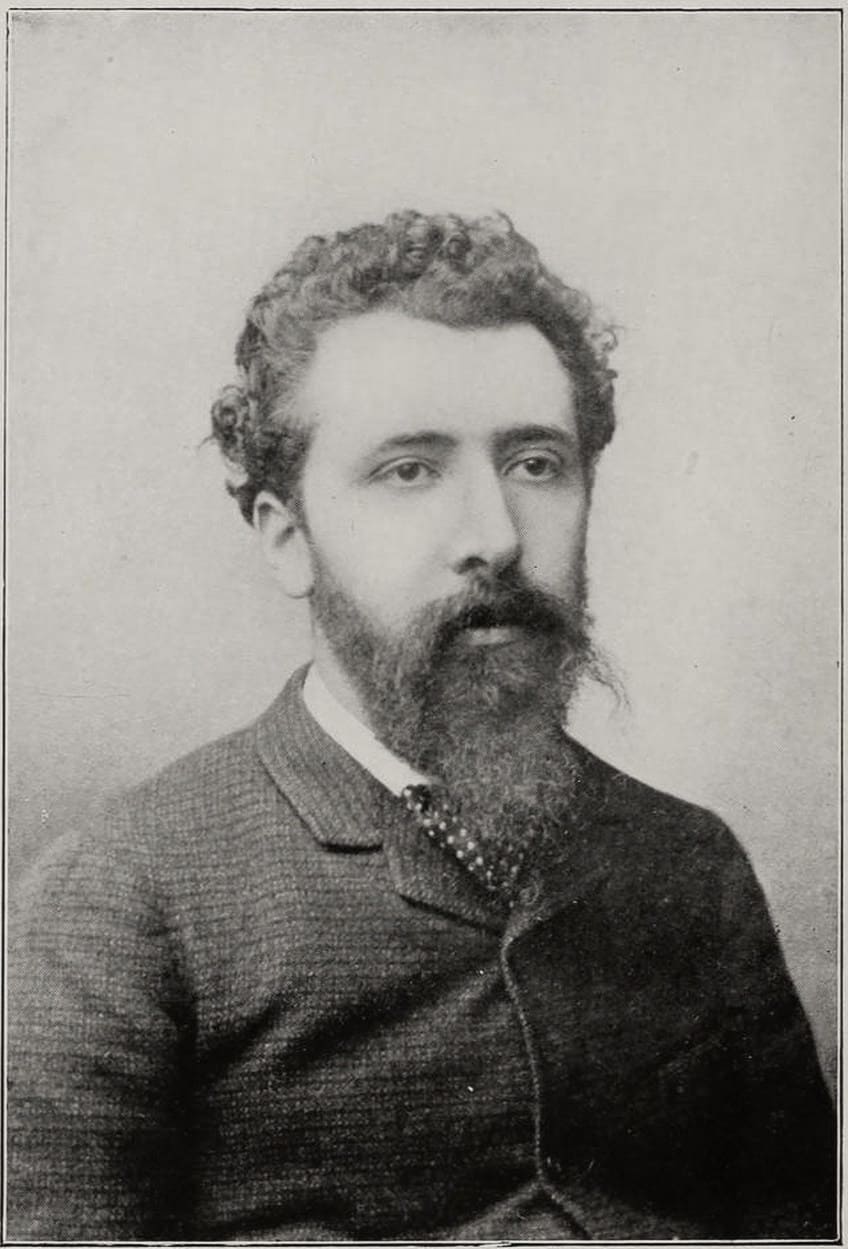

Seurat declared that his goal in quitting the École des Beaux-Arts, where he had spent a year studying, was to “discover something new, my distinctive method of painting”, in 1879.

He took detailed notes on the application of color by the artist Eugène Delacroix because he placed a special priority on luminance in paintings. He started researching optical theory and set out on a course that would eventually lead him to create a new aesthetic movement he dubbed Chromoluminarism.

The Neo-Impressionism Theory

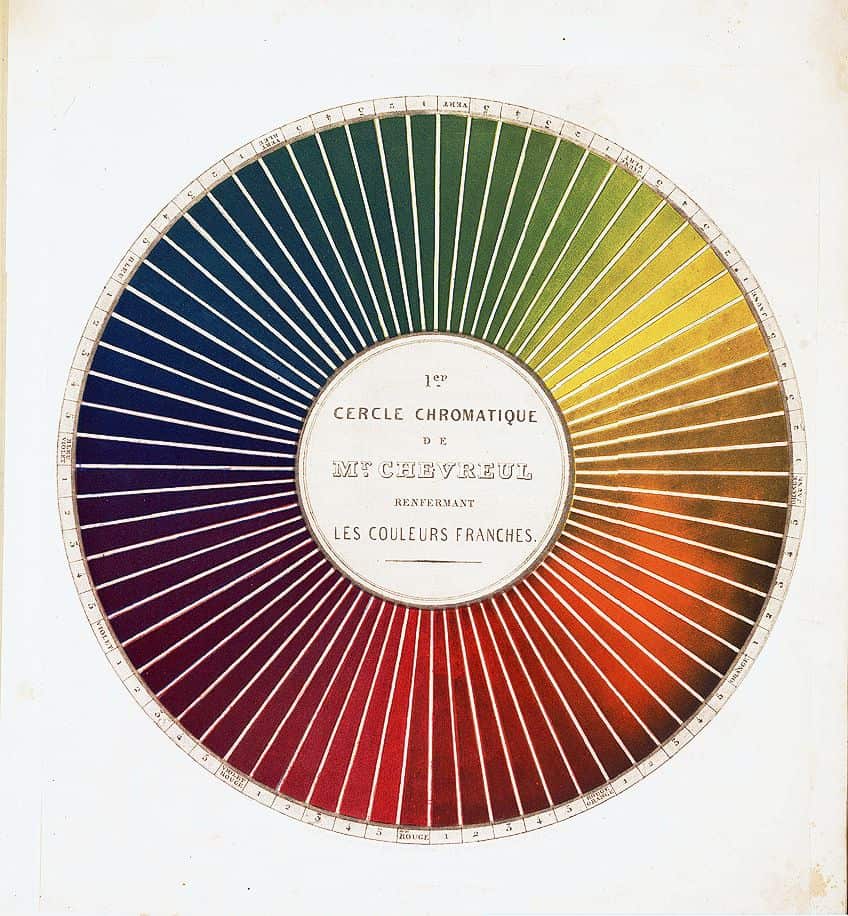

The findings of optical mixing and simultaneous contrast that Georges Seurat learned about provided the theoretical basis for Chromoluminarism, also referred to as Neo-Impressionism art. Michel-Eugène Chevreul had to respond to client concerns regarding the consistency of the yarn’s color while employed at Gobelins dye facility in Paris. While attempting to solve the problem, he uncovered the influence of the color of one yarn on the appearance of the color of another. David Sutter’s Phenomena of Vision (1880) set guides for the connection between artworks and science.

Neo-Impressionism art relies on dots of complementary hues on the canvas to generate the most dazzling colors and a glistening appearance. Instead of blending colors on a palette, Neo-Impressionism artists let the viewer’s eye blend the colors. Though several of these beliefs are today deemed just quasi-scientific, they were cutting-edge at that period. Seurat believed he had found the science behind the art of painting, one that needed discipline and careful application to produce color intensity. He utilized his color theory and a new method that he dubbed balayé, crisscrossing brushstrokes to paint matte colors, in Bathers at Asnières (1884), a colossal piece that shows a lot of laborers swimming in the river on a warm summer’s day.

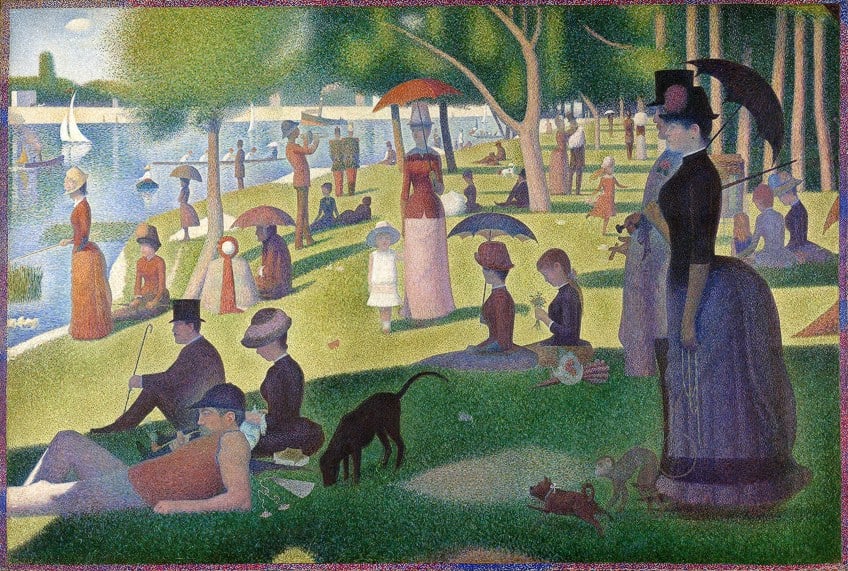

Seurat started working on A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884) by making detailed preliminary research and drawings. The piece, which depicted the bourgeoisie in a park beside the river, utilized the Pointillist style pioneered by Seurat – small dots of complementary colors positioned adjacent to each other.

Seurat’s seminal book on Neo-scientific Impressionism art’s color theory, Esthetique, was released in 1890. Other Neo-Impressionism artists would continue to explore this basis in science; for example, in 1887, Albert Dubois-Pillet devised the concept of passage, in which each of the fundamental light colors’ unique pigment provided a passage between other colors.

The First Generation of Neo-Impressionism Artists

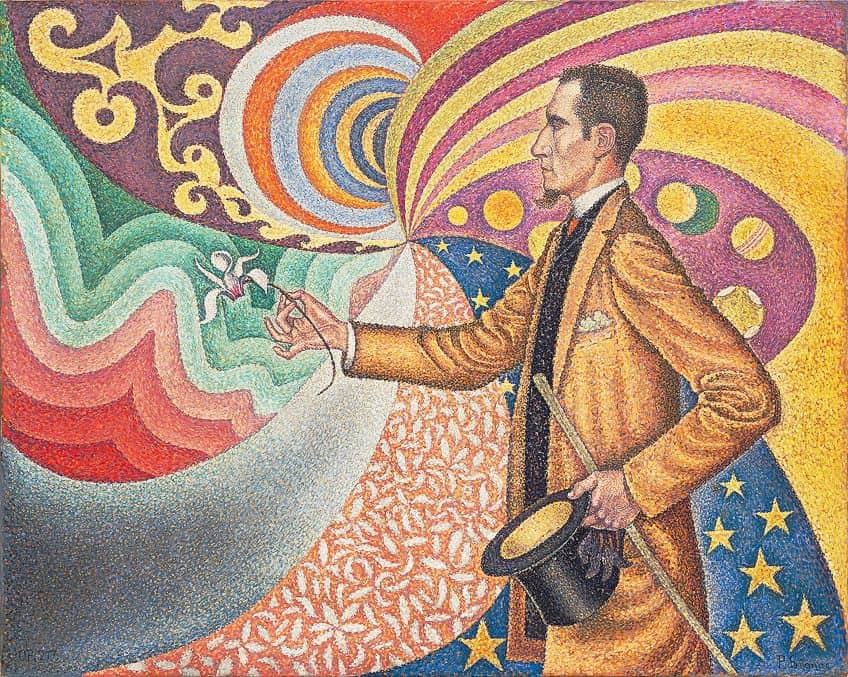

In 1884, the painter Paul Signac met Seurat and subsequently became a firm supporter of both his color theory and his style of creation. Though Seurat was the movement’s austere and restrained theorist, Signac was its outgoing spokesman and promoter. The two individuals had a tight working relationship, and it was Signac who coined the term “Pointillism. Seurat presented Bathers at Asnières to the Academy of Beaux-Arts’ official exhibit, in 1885, but the panel declined it. They were baffled not just by the artwork’s formal structure, gigantic scale, and inventive techniques, but also by Seurat’s representation of lower-class workers in leisure.

In reaction to the rejection, Signac, and Seurat, together with Odilon Redon and Albert Dubois-Pillet, founded the Salon des Indépendants. As a consequence of their meeting in 1885, Camille Pissarro, along with Charles Angrand and Henri-Edmond Cross, formed the first group of Neo-Impressionism artists.

The Emergence of Neo-Impressionism

The year 1886 was a pivotal moment in the art community, as the last Impressionist display also signaled the emergence of Neo-Impressionism art with the presentation of Seurat’s freshly finished artwork. Pissarro, the only painter to have shown in all eight Impressionist exhibitions, encouraged Seurat to join in the show. The painting was again presented at the Société des Artistes Indépendants Salon, where it gained even more recognition, including that of art expert Félix Fénéon, who created the name “Neo-Impressionism” and became an outspoken supporter of the movement in the subsequent years.

Other French painters who joined the trend were Leo Gausson, Maximilien Luce, and Louis Hayet.

Neo-Impressionism and Anarchism

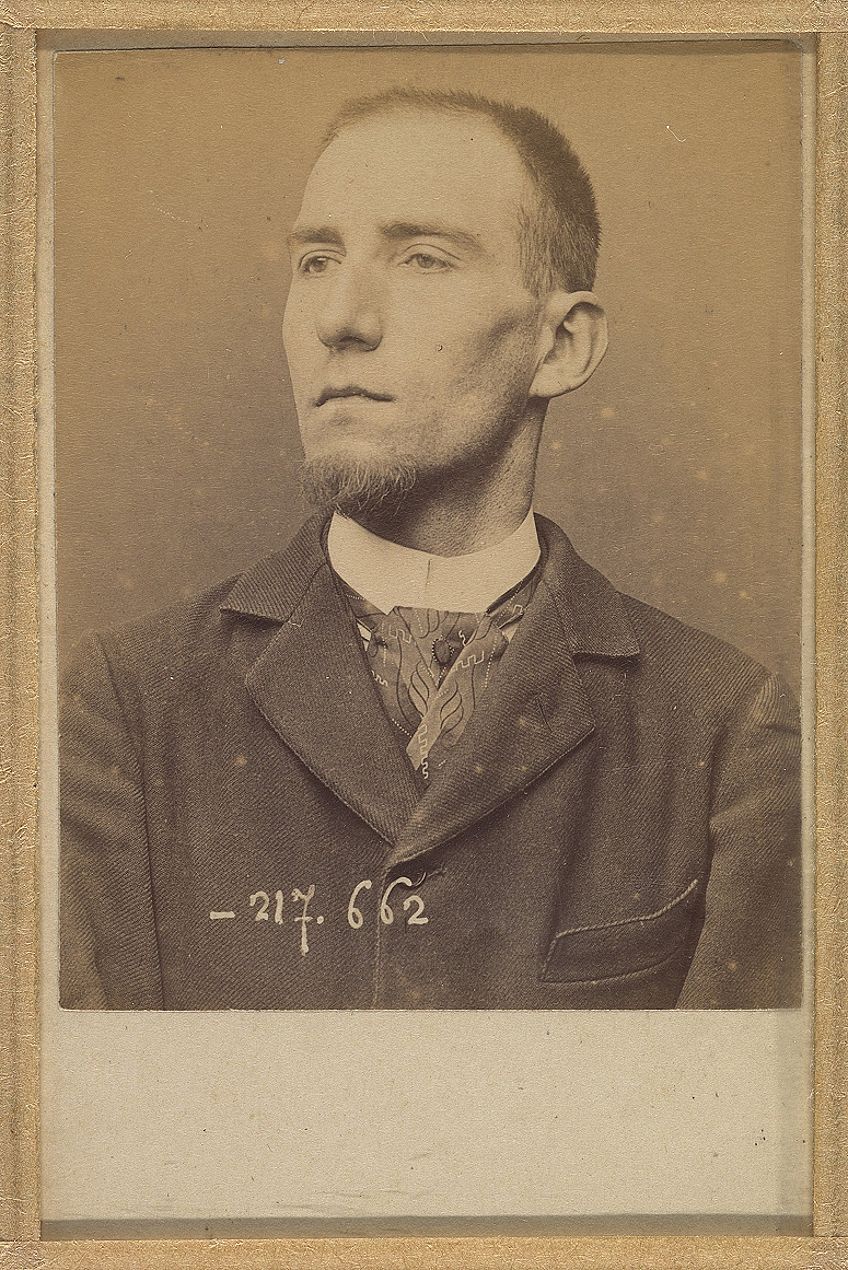

While Seurat’s specific views are unknown, Neo-Impressionism art was always closely linked to the anarchist movement, which had a firm footing in France and the cultural world. Félix Fénéon was well-known for his anarchist beliefs before he became an art critic for La Revue Blanche. Arrested together with 29 others for their anarchist beliefs and accused of conspiracy in the murder of French President Sadi Carnot, all 30 were declared not guilty.

As a consequence of the case, Fénéon established a powerful name for independent thought and rejection of social norms, and as a critic, he associated Neo-Impressionism with anarchist activism. Signac became a dedicated anarchist in the 1880s, helping to support the cause and contributing to the anarchist publication The New Times with Maximilien Luce, Henri-Edmond Cross, and Camille Pissarro.

Signac researched anarchist geographers Peter Kropotkin and Élisée Reclus, as well as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who all advocated for a utopian future based on small communities and free expression. These anarchists gave additional momentum to Signac’s assertion that Neo-Impressionism art was tied to a balance that resulted from human freedoms in a natural context, which shaped much of its subject matter. Additionally, the artists’ pursuit of scientific research supplemented their anarchist ideals by liberating them from the intrusions of bourgeoisie-imposed preferences.

Neo-Impressionism Revival

Seurat passed away at an early age in 1891, and Signac then became the putative head of the group. The publishing of Signac’s manifesto sparked a resurrection of the movement in 1898, transforming it into an international force with anarchist inclinations once again. The manifesto, as well as his paintings such as the Saint-Tropez Storm (1895), attracted a new generation of painters, including Henri Matisse. Signac was elected president of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1908 and served in that capacity until 1934, the year before his death, fighting for Neo-Impressionism art.

Cross and Signac also influenced other painters by introducing stylistic alterations to Neo-Impressionism. Signac started employing rich color, as shown in his 1898 Capo di Noli with its pinkish mountains, and instead of painting in dots, he utilized little brushstrokes that offered dynamic flexibility. Cross utilized circular brushstrokes of varied sizes to create a feeling of perspective as the smallest dots neared the horizon in his seascape The Golden Isles (1892). The artwork is noted for its near abstract aspect, as well as the impact of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints in its lofty horizon.

The mosaic-like effect of his paintings, such as his 1896 La Plage de Saint-Clair, affected his peers the most. Cross achieved this appearance by painting tiny parts of the canvas with quick, sweeping brushstrokes that resembled little blocks. The focus was on keeping opposing colors distinct rather than blending them. Cross was “much more concerned in generating harmonies of pure colors than in matching the hues of a specific landscape or natural scene”, he remarked.

The Geographical Variations of Neo-Impressionism

Neo-Impressionism art had become an international style by the 1890s, with many European painters embracing it. The movement’s dependence on color theory and usage of little dots or brushstrokes remained surprisingly constant. As a consequence, geographical variations are the best way to arrange its growth.

Neo-Impressionism in France

In France, Neo-Impressionism drew a large number of painters of succeeding generations, each of whom modified the style to his or her own preoccupations. The trend was taken up by a few Impressionists, notably Charles Angrand and Camille Pissarro. Using the Pointillist method, Pissarro maintained the emphasis of his work on country life and peasant duties. Angrand employed a more subdued palette to express shadow and tone in his 1887 painting Couple in the Street.

Maximilien Luce painted more modern themes, which he frequently rendered passionately with great contrasts of light. With the resurgence of the style in the 1890s, Neo-Impressionism influenced a new generation of painters. Signac was affected by Cross’s mosaic-like works, as were younger painters such as Henri Manguin, Henri Matisse, Robert Delaunay, Jean Metzinger, and André Derain.

Individual adaptations of the technique may be observed in Delaunay and Metzinger’s use of tiny brushstrokes to mimic little cubes of color, and in Matisse’s development toward an increasingly intense color palette.

Neo-Impressionism in Belgium

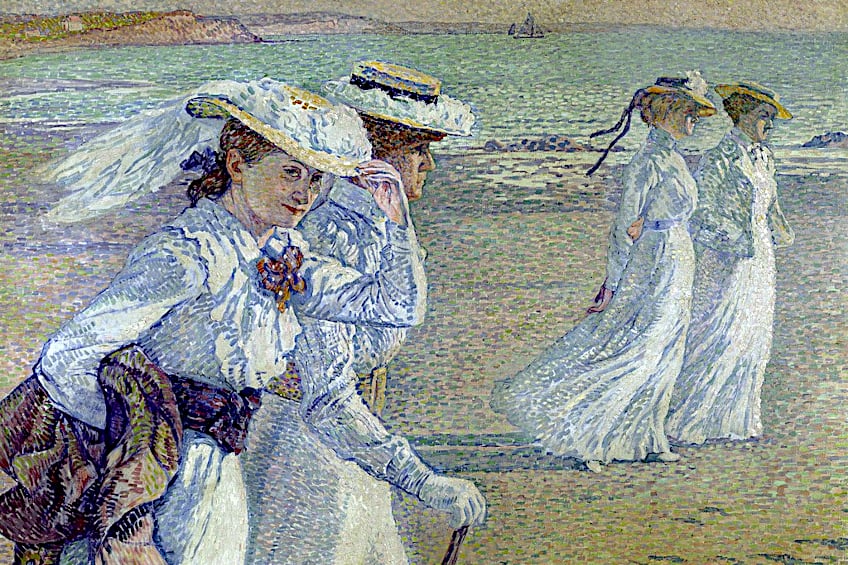

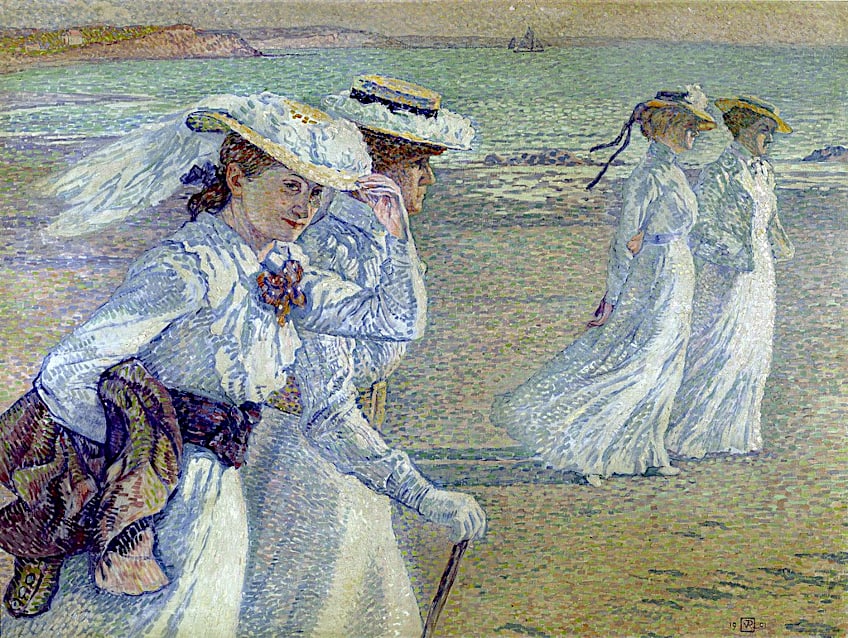

When Belgian Impressionist Théo Van Rysselberghe saw Seurat’s iconic painting in Paris in 1886, he was astounded. Along with a number of other painters, including Xavier Mallery, Georges Lemmen, Henry Clemens van de Velde, Willy Schloback, Alfred William Finch, and Anna Boch, he brought the movement to the Belgian art community where it had a considerable effect.

Van Rysselberghe made a variety of landscapes in the pointillist style during his Moroccan trips, yet, it was his 1888 Portrait of Alice Sethe that became his hallmark piece. Portraiture became an important component of Belgian Neo-Impressionism as a result of his impact.

Alfred William Finch, a founder member of a Brussels group that attempted to rescue Belgian art from restrictive patriotic traditions by focusing on French current models, known as Les Vingt saw Signac and Seurat’s works at the Les Vingt display in 1886 and became a huge advocate. Breaking Waves at Heyst (1891), which depicts an empty sky over a raging sea, with a significant focus on patterning and designs, has a flat and ornamental impact. The concentration on color and patterns is also visible in the art of Henry Clemens van de Velde.

Neo-Impressionism in Holland

Jan Toorop studied in Brussels from 1882 to 1890, when he became acquainted with the work of Signac and Seurat. He established a distinctive style that combined Divisionism art with other creative influences he had encountered, and he was considered a significant pioneer in Holland. Broek in Waterland is an 1889 Neo-Impressionist painting portraying a couple on a rowboat along a canal at sunset, with a significant pattern and design element. He became a member of the Hague Art Circle and helped arrange an exhibition with works by Signac, Seurat, Pissaro, Van de Velde, and others.

The show garnered a lot of positive attention and was attended by Van de Velde, who formed a lot of important ties with Dutch artists. As a consequence, young painters like Petrus Bremmer, Johan Joseph Aarts, and Jan Vijibrief established themselves as Neo-Impressionists. Bremmer had a great impact as a teacher and writer, advocating for the adoption of a bright, clean palette. However, Piet Mondrian and Vincent van Gogh were the most notable inventive Dutch painters to embrace Pointillism early in their careers.

Van Gogh visited Signac in Paris in 1887 and incorporated parts of the technique into his own form of expression. Mondrian embraced the approach and remarked in 1909, “I feel that, as far as possible, paint should be put in pure colors positioned next to each other in a pointillist or diffused way in our day. This is articulated powerfully, yet it refers to the concept that serves as the foundation for significant expression in form”. Both artists progressed beyond Divisionism art to seek and create new aesthetic approaches.

Neo-Impressionism in Italy

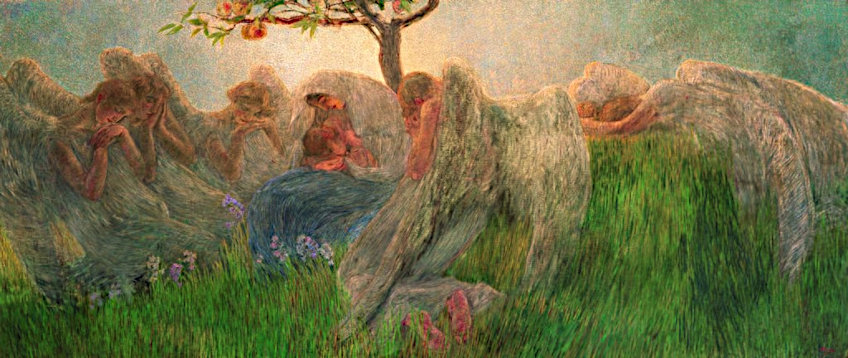

In the late 1880s, the painter and critic Vittore Grubicy de Dragon presented Divisionism art to Italian painters. He lived in the Netherlands from 1882 to 1885, when he met and was inspired by the painter Anton Mauve, a cousin of Vincent van Gogh and a supporter of the movement. Two Divisionism artworks drew the greatest attention at the First Triennale in Milan in 1891. The Two Mothers (1889) by Giovanni Segantini, who had international renown, was well received, whilst Gaetano Previati’s Motherhood (1891) was brutally criticized.

Previati had studied Divisionism art in depth and had authored the sole scholarly treatise on the subject at the time. While he was well-versed in color perception, he also believed that by employing bright colors to powerfully engage the eye, a spiritual and emotional connection would be felt.

Motherhood is now recognized as the founding piece of Italian Neo-Impressionism and a turning point in Italian contemporary art because of its interplay with Symbolism and its influence on Italian Art Nouveau and Expressionism. While the artwork generally focused on landscape, it mirrored Segantini’s stance that painting has nothing to do with replication of the actual world, because creativity is only attainable through the impulse of the imagination and the human soul. The artist Cesare Viazzi praised Giuseppe Pelizza da Volpedo’s The Mirror of Life (1898), representing a group of sheep in a field, as portraying the real feeling of perfect serenity contained in the graceful surrender of nature.

Many of the pieces were Symbolist or metaphorical in nature, with the intention of responding to societal realities. Pelizza’s most renowned work was Il Quarto Stato, which he created in 1901.

Neo-Impressionism in Germany and Austria

The 1890s were a time of Secessions, or art groups that rebelled against the rigidity of formal academies and promoted contemporary art. The Munich, Vienna, and Berlin Secessions had no manifesto and displayed the works of all contemporary trends, with Neo-Impressionism art taking center stage. Curt Hermann, a Berlin artist, adapted the approach, mixing it with the realism of en Plein air painting.

The style, though, had the biggest impact on a newer group of painters. Following the German translation of Signac’s writings in 1903 and the 1904 Neo-Impressionism art exhibition, Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner created Divisionism artworks. Other young painters, such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluf and Erick Heckel, took the approach and pushed it into Expressionism, as evidenced in Heckel’s frantic brush strokes depicting churning water.

For these painters, Neo-Impressionism was a worldwide style that shattered Impressionist art’s supremacy, enabling them to focus only on the qualities and possible effects of color.

Later Developments

Neo-Impressionism art continued to influence individual artists and the development of art movements including Fauvism, Cubism, Art Nouveau, Orphism, Die Brücke, Italian Futurism, and the push for abstraction even beyond Seurat’s passing in 1891. Neo-Impressionism demonstrated a potential for abstraction – in the meaning of “to remove from” – as a component of its modernity. It extracted formal features, fundamental archetypes, color experiences, and lines from the environment, which would serve as the starting point for many modernist attempts. While several painters experimented with the method before moving on to other genres, Signac, one of the founding Neo-Impressionists, painted in this manner until his passing in 1935.

The emphasis on color and the feelings it created in the spectator prompted a departure from realistic renderings of color. Matisse’s 1904 work Luxury, Calm, and Pleasure introduced Fauvism. Other Fauvist figures, like Maurice de Vlaminck and Andre Derain, produced Divisionist landscapes. Among others, Metzinger and Delauney transformed the thin brush strokes of later Neo-Impressionism into compact cube-like forms. Metzinger was influenced by these little “cubes” and Seurat’s concentration on geometry in painting as he advanced toward Cubism. Seurat’s geometry also impacted Georges Braque’s Cubism.

Finch, a Belgian Neo-Impressionist, subsequently worked as a ceramicist in Finland, where he helped define the region’s Art Nouveau style. Color patterns inspired Henry Clemens van de Velde, who eventually became one of the pioneers of Belgian Art Nouveau.

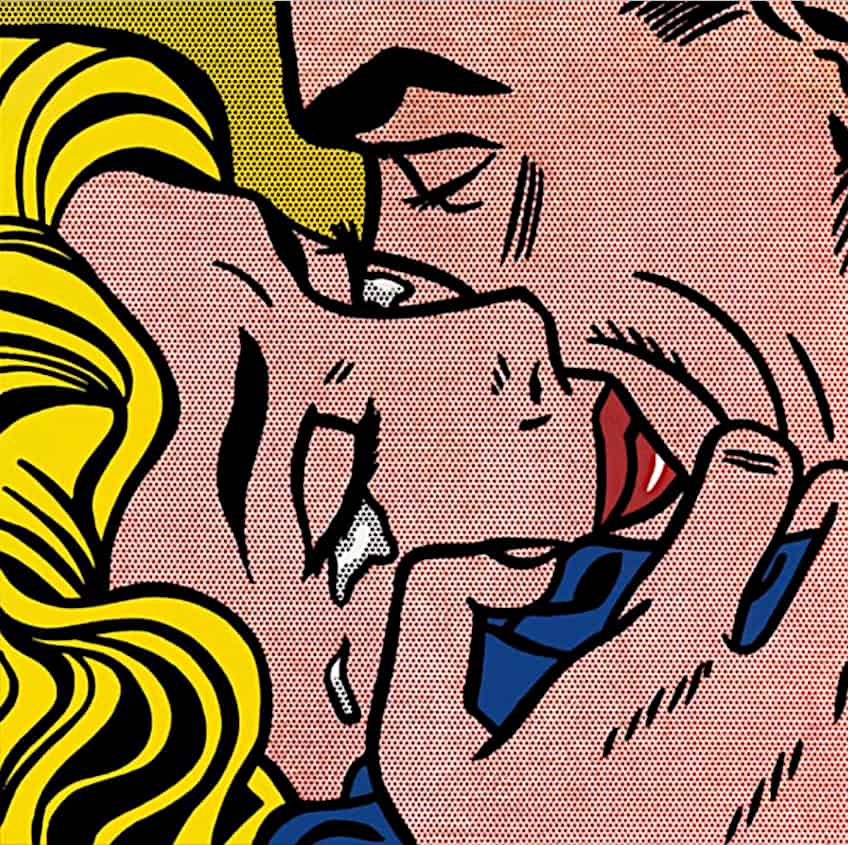

Signac’s later work, with its ornamental effects and arabesque patterns, had a significant influence on the growth of Art Nouveau among some of the artists of the Munich, Vienna, and Berlin Secessions. Neo-Impressionist methods and beliefs continue to impact modern artists. Roy Lichtenstein, an American Pop artist, produced pieces like Kiss V (1964) by employing stencil dot patterns that remind not just of the printing of newspapers and magazines, but also of the specks of color in Neo-Impressionism artworks.

The employment of the divisionist method distinguishes Neo-impressionism. Divisionism art aimed to scientifically ground Impressionist paintings of light and color by employing an optical color combination. Rather than combining colors on the palette, which diminishes intensity, the primary-color components of each color were placed individually on the canvas in small dabs so that they would combine in the spectator’s eye. Because optically blended colors gravitate towards white, this approach produced more brilliance.

Take a look at our Neo-Impressionism art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Neo-Impressionism Art?

Based on the Neo-Impressionism definition, it was a phrase established in 1886 by French art critic Fénéon to describe an avant-garde art movement that thrived primarily in France from 1886 until 1906. The Neo-Impressionism artists, led by Georges Seurat, rejected the immediacy of Impressionism in lieu of a calculated painting approach based on science and the understanding of optics. Neo-Impressionism artists came to feel that distinct spots of pigment result in greater color vitality than the traditional mixing of colors on the palette.

What Is Divisionism Art?

Pointillism and Divisionism art, two concepts frequently linked with Neo-Impressionism, are nearly interchangeable. Broadly speaking, Divisionism is a color theory that promotes putting tiny areas of pure color individually on the canvas so that the audience’s eye will optically combine the colors. Divisionism was generally ascribed to any artist who divided or separated color with little brushstrokes. Pointillism used the same optical mixing method, but used small distinct dots of color.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Neo-Impressionism – History and Development of Divisionist Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. June 6, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/neo-impressionism/

Davis, L. (2023, 6 June). Neo-Impressionism – History and Development of Divisionist Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/neo-impressionism/

Davis, Liam. “Neo-Impressionism – History and Development of Divisionist Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, June 6, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/neo-impressionism/.