“Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – An In-Depth Analysis

The Salvator Mundi painting must surely be one of the most contentious pieces of artwork of our time: When it sold, the Salvator Mundi’s price was $450.3 million, yet many scholars still doubt it was produced by Leonardo da Vinci. The Jesus painting portrays Christ as the savior of the world, holding a globe that represents the earth in one hand. In this article, we will discuss the Salvator Mundi restoration and sale, and find out who bought Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci.

A Look at Salvator Mundi (1510) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) |

| Year | 1510 |

| Medium | Oil on walnut panel |

| Location | Collection of Mohammad bin Salman |

There are a few stories regarding who bought Salvator Mundi. At the actual auction it was officially bought by Prince Badr bin Abdullah Al Saud, however, many believe that he was there on behalf of Mohammed bin Salman. In 2017 some reports stated that the Jesus painting would be displayed at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, yet in September 2018, the unveiling was canceled.

The current location of the Salvator Mundi painting is unknown, with reports stating that it was in storage on Mohammed bin Salman’s yacht.

History of Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci

Art historians have offered many theories for when the piece was completed and who the sponsor might have been. According to Christie’s, it was most likely commissioned in approximately 1500, soon after France’s King Louis XII took control of Genoa during the Second Italian War.

Leonardo da Vinci himself relocated to Florence from Milan in 1500.

16th Century: Origins and Copies

Because of the specific nature of the subject, Salvator Mundi was most likely commissioned by a particular client rather than created on the spur of the moment. The Duchess of Milan, Isabella d’Este, is mentioned as a possible patron since in 1504 she wanted Leonardo da Vinci to create a “young Christ of roughly 12 years” however the Salvator Mundi painting depicts a more adult Christ.

In 1514, Isabella d’Este was a guest of Giulianio de Medici, Da Vinci’s patron, and may have persuaded the artist to finish the project at that time. Others said it was painted for King Louis XII of France.

Origins

The artwork, like other panels of similar size and topic in the 16th century, would have been employed for personal devotion. Indeed, historian Joanne Snow-Smith stresses in her literature Louis XII’s devotional connection with the Salvator Mundi as a theme, and other historians have pointed out the artwork’s connection to illuminated manuscripts from France in the practice of early 16th-century private prayer and devotion.

As an image type, the Salvator Mundi predates Leonardo da Vinci.

Thus, some historians claim that while Da Vinci’s creation was bound by the traditional iconography of the Salvator Mundi, he was able to employ the imagery as a channel for spiritual connection between the viewer and the figure of Christ. The arrangement is based on Byzantine art, the iconography of which evolved in Northern Europe before reaching the Italian Republic. Joanne Snow-Smith traces the theme of the Salvator Mundi back to Byzantine imagery and stories of pictures of Christ “not produced by human hands”.

Although the Salvator Mundi derives from the acheiropoeta (tradition of paintings not believed to be produced by human hands), it first appeared in the 15th century through transitional themes such as Christ as Pantocrator, which, like the acheiropoieta, reveal its Byzantine roots through frontal portrayals of Christ. Other images of Christ from the 15th and 16th centuries share this frontality, such as “portrait” images of Christ that display only Christ at half-length with no orb or gesture of blessing, as well as representations of “Christ Blessing” that do not display Christ carrying an orb.

After Charlemagne’s embrace of the globus cruciger, images of Christ bearing a sphere became quite popular.

Northern Europe has the oldest real Salvator Mundi illustrations. The picture of Salvator Mundi later became well recognized in Italy, particularly in Venice, because of the version by Giovanni Bellini, which is now only known through reproductions.

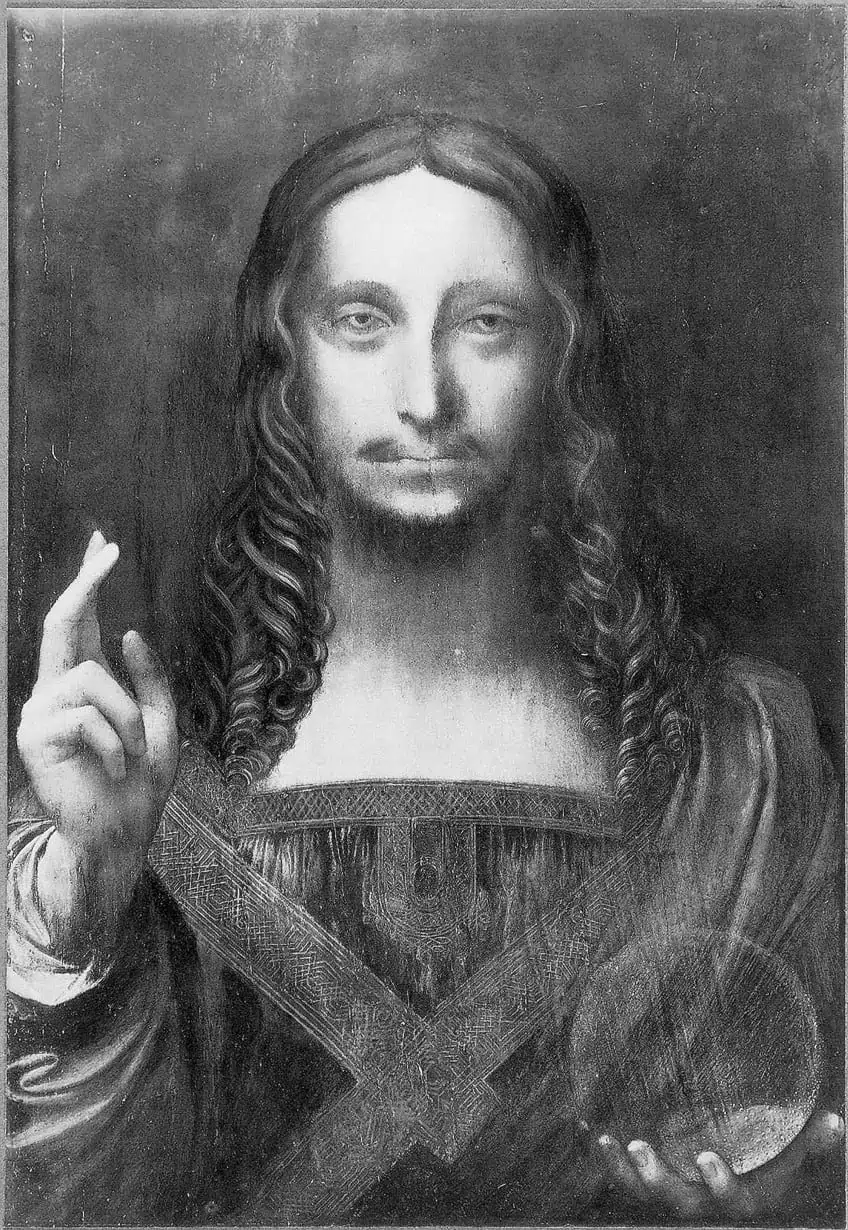

Copies

According to Robert Simon, there are at least 30 copies and modifications of the work created by Da Vinci’s students and admirers. The vast number of these copies reflects how influential Da Vinci’s painting style was and supports the idea of an original by Da Vinci from which they were reproduced. The picture previously in the De Ganay collection is the most noteworthy and most debated of all, as it bears the same composition and exhibits the best technical proficiency of Da Vinci’s pupils. In 1978, Joanne Snow-Smith even suggested it was the original picture.

Many more replicas, including those in Detroit, Naples, Zürich, Warsaw, and other private and public collections, are attributed to members of Leonardo da Vinci’s students and admirers.

Some versions are drastically different from the source painting. Da Vinci’s studio and followers also created at least four Salvator Mundi panels picturing a younger Christ in a less frontal position holding a terrestrial globe. These are mostly from Da Vinci’s Milanese followers instead of studio members.

However, the version in Rome can be credited to his disciple Marco d’Oggiono.

17th Century to the 19th Century

From 1638 until 1641, this Jesus painting appears to have been at James Hamilton’s Chelsea Manor in London. Hamilton was murdered on the 9th of March, 1649, after taking part in the English Civil War, and some of his belongings were sent to the Netherlands to be auctioned. Wenceslaus Hollar, the Bohemian artist, might have created his etched replica, dated 1650, in Antwerp at that time.

It was also identified in the possession of Henrietta Maria on the 30th of January, 1649, the very same year her husband Charles I was murdered.

The artwork was part of a Royal Collection catalog estimated at £30, and Charles’ assets were auctioned off under the English Commonwealth. The artwork was bought by a creditor in 1651, restored to Charles II during the 1660 English Restoration, and was listed in a 1666 list of Charles’ assets at the Palace of Whitehall. In the 19th century, the artwork was most likely set in a gilded frame, where it stayed until 2005.

The picture had been damaged by prior restorative efforts and was assigned to Da Vinci disciple Bernardino Luini.

Rediscovery and Restoration Efforts

The original Da Vinci artwork was supposed to have been damaged or lost in about 1603. Snow-Smith suggested in 1978 that the replica in the possession of the Marquis Jean-Louis de Ganay was the missing original, citing similarities to Da Vinci’s Saint John the Baptist. While Snow-Smith conducted an extensive study into the painting’s origin and link to Hollar, few scholars agreed with her identification.

A Salvator Mundi was auctioned off in 2005 at the St. Charles Gallery in New Orleans, submitted by the family of Baton Rouge industrialist Basil Clovis Hendry Sr.

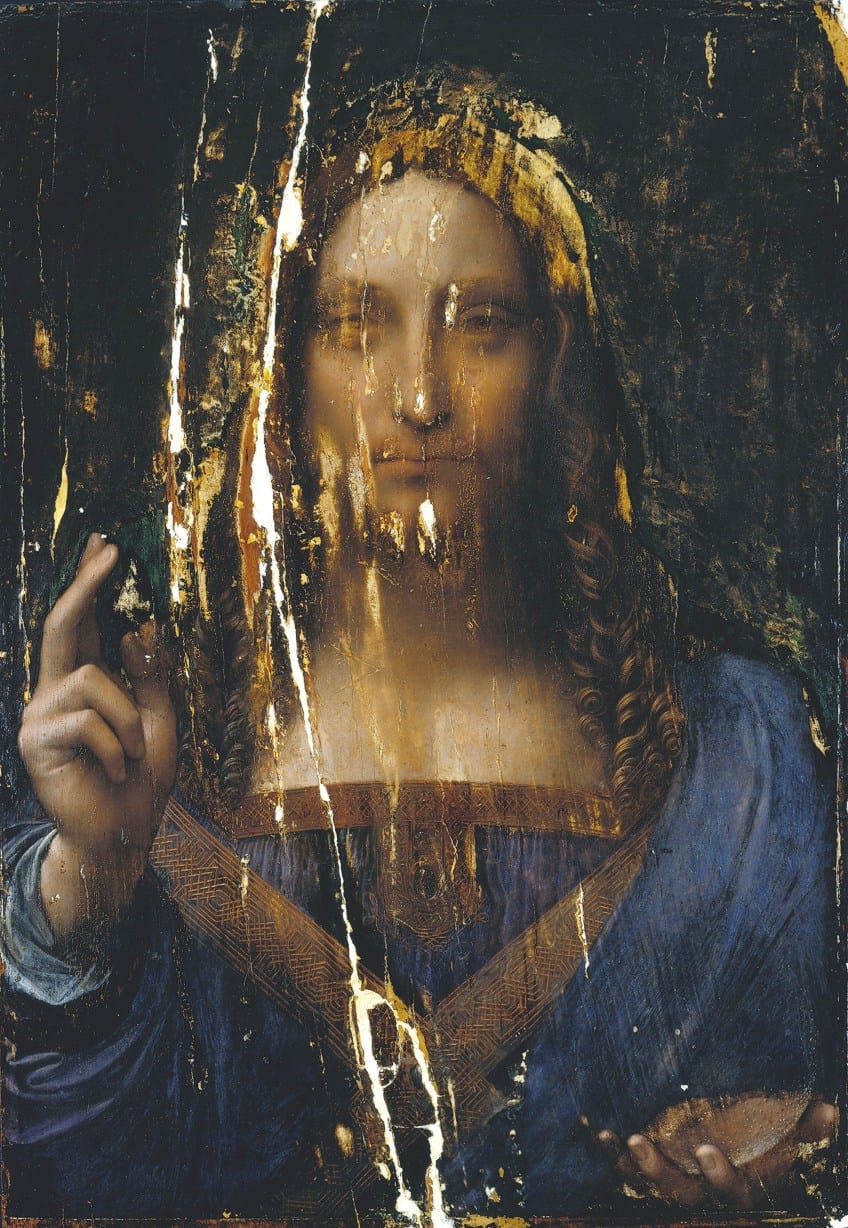

It had been significantly overpainted to the extent that the artwork looked like a duplicate and was characterized as “a disaster, dark and dismal” before restoration. It was purchased by a group of art traders that comprised Robert Simon, an Old Masters specialist, and Alexander Parish. The painting cost $1,175 in total to the consortium.

The group suspected that this apparently low-quality artwork may be Leonardo da Vinci’s long-lost original, so they appointed Dianne Dwyer Modestini of New York University to supervise the restoration process.

When Modestini started eliminating the overpainting with acetone at the start of the repair process, she noticed that a stepped patch of unevenness around Christ’s head had been shaved with a sharpened tool and leveled with a combination of paint, gesso, and glue at some time.

Restoration

Modestini uncovered a pentimento (a vestige of an older composition) with the benediction hand’s thumb in a straighter, instead of curved, orientation using infrared pictures Simon had captured of the painting. It was critical to discover that Christ had two potential thumb placements on his right hand. This pentimento demonstrated that the original artist had revised the posture of the figure.

Such consideration is regarded as proof of an original, instead of a copy, because a painting reproduced from the completed original would not have such a change mid-painting process.

Modestini then had Monica Griesbach, a panel expert, chisel out a marouflage panel infested with woodworm that had caused the painting to split into seven parts. Griesbach rebuilt the artwork using glue and slivers of wood. Modestini started her repair work in late 2006.

Art historians blasted the outcome, saying that “both thumbs” of the artwork’s raw condition “are far superior to the one repainted by Dianne.”

Leonardo da Vinci was subsequently authenticated as the artist of the Jesus painting. After being authenticated by London’s National Gallery, the picture was displayed as an original work by Da Vinci from November 2011 to February 2012. The Dallas Museum of Art also validated it in 2012.

Attribution

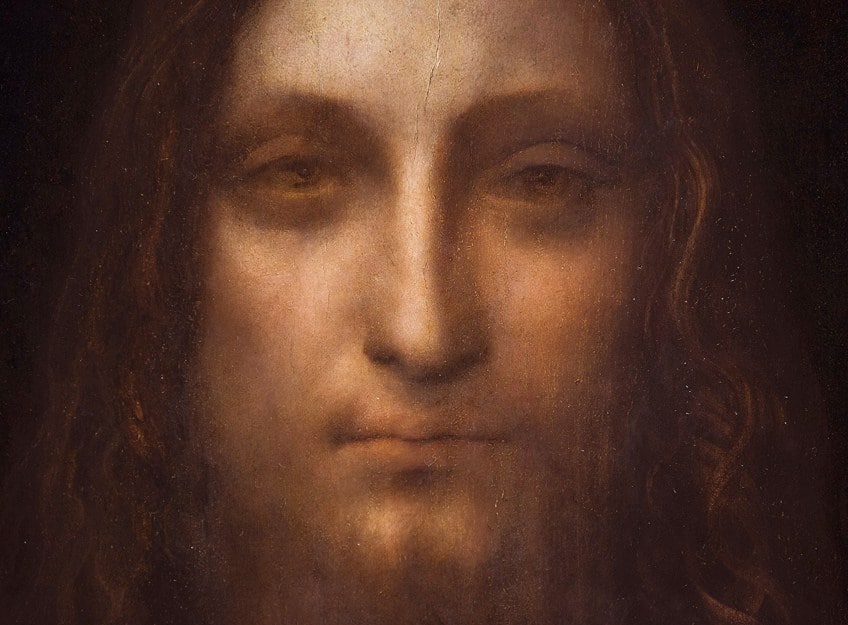

Dianne Dwyer Modestini commented about a year into her restorative attempt that the color transitions in the subject’s lips were “excellent” and that “no other painter could have accomplished it.” She determined after examining the Mona Lisa (1503) that “the painter who produced her was the same hand that had produced the Salvator Mundi.”

She has since distributed high-resolution photographs and relevant information online to the scientific community and the general public.

The National Gallery’s director, Nicholas Penny, said in 2006 that he and several of his colleagues thought the piece was an original Da Vinci, but that “a few of us feel that there could be elements which were produced by the workshop”. Penny studied the Salvator Mundi and the Virgin of the Rocks side by side in 2008. “I left the studio believing Leonardo da Vinci must have been actively involved,” Kemp later remarked of the discussion, and “no one in the audience was vocally expressing skepticism that he was involved in the painting”. After being cleaned and restored, the artwork was compared to 20 other renditions of the subject and deemed to be superior.

A good amount of pentimenti is visible in the picture, most notably the location of the right thumb, which has led to the conclusive attribution. The sfumato look of the face, presumably accomplished in part by applying the paint with the heel of the hand, is characteristic of many of Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings. Leonardo da Vinci’s style may also be observed in the way the wavy curls of hair and the knotwork over the robe have been handled.

Additionally, the colors used in the piece, as well as the walnut panel on which it was created, are comparable with earlier Da Vinci works.

Furthermore, the hands in the picture are incredibly detailed, which is characteristic of Leonardo da Vinci: He often dissected the limbs of the dead to examine them and reproduce body parts in an exceptionally realistic manner. When Martin Kemp, one of the foremost Leonardo da Vinci scholars in the world, first saw the restored picture, he immediately recognized it as a Leonardo creation: “It had that type of character that has that uncanny weirdness that the subsequent Da Vinci paintings express”.

Partial Attribution

Some reputable Renaissance art scholars challenge the painting’s entire provenance to Leonardo da Vinci. According to Jacques Franck, a specialist in Da Vinci’s work who has examined the Mona Lisa out of the frame several times: “Leonardo da Vinci did not create the composition; he liked twisting movement.

It’s a nice studio piece with just a little Da Vinci, and it’s badly damaged. It has been dubbed “the manly Mona Lisa,” yet it bears little resemblance to the famous painting”.

Michael Daley questions the Salvator Mundi‘s authenticity and hypothesizes that it could be the original version of a topic that Da Vinci painted. He writes, “This pursuit for a prototype Da Vinci painting might appear completely pointless: not only do the two fabric studies encompass the only acknowledged Leonardo content that might be affiliated with the group, but inside the Da Vinci literature there is no documentation of the artist ever having taken part in such a project”.

An expert in Italian Renaissance art, Carmen Bambach, brought into question the full authorship to Leonardo da Vinci: “Having researched and followed the image during its preservation procedure, and having seen it in in the framework in the National Gallery exhibition, the majority of the existing portrait surface could be attributed to Boltraffio, with certain parts done by Da Vinci himself, notably Christ’s proper right blessing hand, sections of the sleeves, and the crystal orb he possesses.

Bambach criticized Christie’s in 2019 for asserting that she was one of the specialists who had identified Da Vinci as the creator of the artwork.

In her 2019 publications, she is much more unambiguous, crediting Boltraffio with most of the effort and the master himself for just slight alterations. In Paris, the Louvre received no answer to its request to include the Salvator Mundi painting in its Da Vinci exhibition in 2020. The French refused to accede to Saudi requests that the artwork is shown next to the Mona Lisa, according to a story in the New York Times from April 2021. However, as the Louvre was unable to respond to inquiries about the situation in the interval, rumors began to circulate that there were questions about the painting’s complete provenance to the artist.

Rejection of the Da Vinci Attribution

Charles Hope, a British art historian, completely rejected Leonardo da Vinci’s attribution in a January 2020 evaluation of the painting’s grade and origin. He questioned if Da Vinci would have produced a piece where the draperies were not warped by a crystal ball and the eyes were not level.

The image itself is a disaster, but the face has been extensively repaired to resemble the Mona Lisa, the speaker said.

Hope criticized the National Gallery’s participation in Simon’s “shrewd” marketing strategy. In August 2020, Jacques Franck asserted that the Salvator Mundi painting was not created by Da Vinci and pointed to its “immaturely conceived left hand, strangely long and slim nose, simplistic mouth, and overshadowed neck” as proof. Franck had previously described the portrait as “a good workshop canvas with a little Da Vinci at best”. More specifically, Franck now credits Sala and Boltraffio with creating the Jesus painting.

This is because the infrared reflectogram of the piece reveals a highly unique sketching-out method that is not present in any of Da Vinci’s art pieces but is present in Salai’s.

Reception

The found Leonardo da Vinci artwork sparked a lot of media and public curiosity before the auction in London, Hong Kong, San Francisco, and New York, as well as following the sale. The artwork was viewed in person by more than 27,000 individuals before the auction, which according to Christie’s is the greatest number of spectators for a single work of art. Christie’s has never advertised a piece of art through a third party before the sale.

On the weekend before the auction, 4,500 people waited in line to see the piece in New York.

Following its sale, the artwork became a hot topic in popular culture and internet discussion due to its sensationalism. In response to the sale, “the internet went a bit nuts,” as Brian Boucher put it, sparking witty and caustic remarks and memes on Instagram, Twitter as well as other social media platforms. Marion Maneker likened the sensationalism surrounding Salvator Mundi to the media hype following the disappearance of the Mona Lisa in 1911 from the Louvre. She contended that just as worldwide media sensationalism propelled the artwork to a high international stature, Christie’s marketing strategy and media sensationalism were responsible for its high selling price.

Playwrights and filmmakers are intrigued by the stories around the picture. A Broadway musical centered on the history of Salvator Mundi is being developed, according to a July 2020 announcement by the business Caiola Productions.

The Savior for Sale, a feature-length documentary directed by Antoine Vitkine and released in April 2021, focuses on the Salvator Mundi painting and its absence from the Louvre’s 2020 Da Vinci exhibition.

A short while later, in June 2021, Andreas Koefoed’s documentary The Lost Leonardo had its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival. It focused on the controversy surrounding the artwork’s provenance and origin as well as its absence from the 2020 Louvre exhibition.

The Salvator Mundi painting by Leonardo da Vinci has a long and interesting history. And its story seems to be far from over since it has drawn even more critical reviews since the Salvator Mundi’s restoration. Was the Jesus painting an actual Da Vinci original or was it created by one of his workshop students? Despite not knowing the real origins of the painting, it has still managed to capture the attention of the art world and sell for a pretty penny on the market.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Salvator Mundi’s Price?

Salvator Mundi (1510) by Leonardo da Vinci was sold at auction in 2017 by Christie’s in New York. It sold for more than $450 million dollars. This makes it the most expensive artwork to be sold yet.

Who Bought Salvator Mundi?

There is some doubt as to who bought Salvator Mundi. Originally, Salvator Mundi (1510) by Leonardo da Vinci was bought by Prince Badr bin Abdullah Al Saud. Yet, many believe that he was just sitting in for Mohammed bin Salman. Of course, one would have to be a Saudi Arabian prince to afford such an incredibly expensive artwork.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, ““Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – An In-Depth Analysis.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 31, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/salvator-mundi-by-leonardo-da-vinci/

Anthony, J. (2022, 31 October). “Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – An In-Depth Analysis. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/salvator-mundi-by-leonardo-da-vinci/

Anthony, Jordan. ““Salvator Mundi” by Leonardo da Vinci – An In-Depth Analysis.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 31, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/salvator-mundi-by-leonardo-da-vinci/.