Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painting by Michelangelo

A landmark achievement of High Renaissance art, the Sistine Chapel ceiling painting by Michelangelo is still highly regarded today. The many painted components of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel were part of a greater plan of decorating the church building, which included Michelangelo’s enormous paintings as well as wall paintings by other famous artists of the late 15th century. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings included multiple series of individual figures, both fully dressed and naked, allowing him to wholly illustrate his expertise in developing a large variety of postures for the human figure and serving as a hugely impactful template of model types for other creatives ever since.

The Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painting by Michelangelo

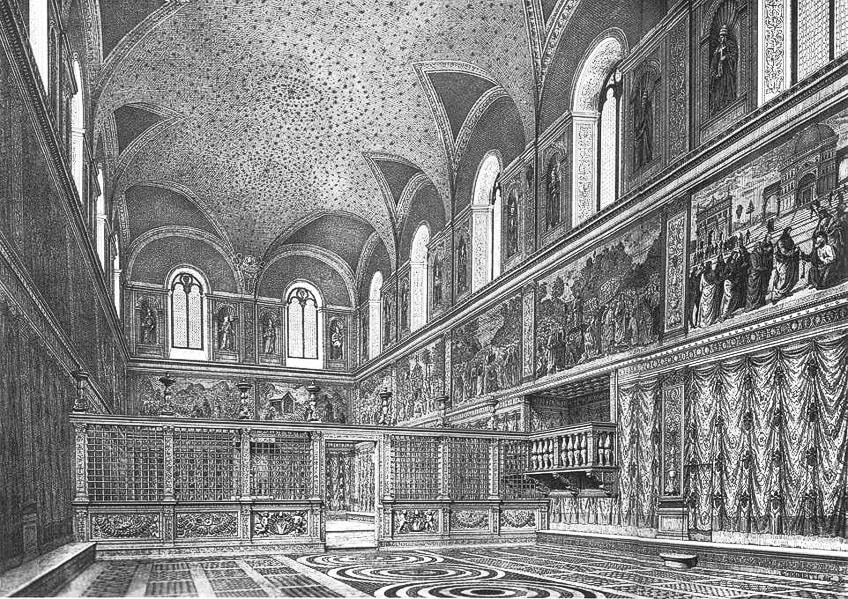

The chapel is where papal coalitions and other major events are held. Nine episodes from the Book of Genesis are fundamental to the Sistine Chapel artwork. But when was the Sistine Chapel painted and how long did it take to paint the Sistine Chapel? Let’s find out!

History and Context

Julius II devised a plan to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in 1506, the exact year the cornerstone for the new St. Peter’s was placed. It is likely that Julius II intended and expected the symbolism of the ceiling to be interpreted with many tiers of significance because the church building was the location of frequent gatherings and Masses of an upper-echelon body of authorities known as the Papal Chapel who would oversee the designs and analyze their scriptural and temporal relevance.

The pope recommended that 12 huge statues of the Apostles fill the pendentives. Michelangelo pushed for a larger, more intricate plan and was eventually allowed to do what he pleased. It has been hypothesized that cardinal Giles of Viterbo affected the theological arrangement of the Sistine Chapel art.

Many historians believe that Michelangelo possessed the brains, theological knowledge, and inventive abilities to develop the idea himself. This is reinforced by Michelangelo’s biographer Ascanio Condivi’s remark that the creator studied the Old Testament while decorating the ceiling, gaining motivation from the contents of the Torah rather than from preexisting sacred art traditions.

Piero Roselli replied with Michelangelo on request of the Pope on the 10th of May, 1506. Roselli writes in this correspondence that Donato Bramante, a papal court architect, questioned Michelangelo’s ability to embark on such a huge fresco project due to his lack of expertise in the medium. Michelangelo voiced his reluctance. Michelangelo traveled to Bologna in November 1506 after receiving a request from the Pope to create a huge bronze monument depicting himself defeating the Bolognese.

Michelangelo went to Rome in early 1508, intending to start work on the papal mausoleum, but this had been discreetly put on hold. Rather, Michelangelo was tasked to design a cycle of paintings for the vault and ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo, who was primarily a sculptor rather than a painter, was hesitant to take on the assignment and advised that his youthful competitor Raphael do so instead. According to Giorgio Vasari, the pope was spurred by Bramante to demand that Michelangelo take on the work, leaving him with no choice but to comply.

The deal was signed on the 8th of May, 1508, with a sum of 3,000 ducats pledged. Bramante erected the original scaffolding, which was strung through ropes from openings in the ceiling, at the request of the Pope. This approach irritated Michelangelo since it required him to paint around the holes, so he had independent scaffolding built instead. Piero Roselli constructed it, and he also roughcast the roof.

He started painting right away, starting with the Prophet Zechariah and Noah’s Drunkenness on the west end and working his way backward through the tale to the Creation of Eve in the vault’s fifth bay, which was finalized in September 1510. The initial half of the ceiling was presented on the 14 of August 1511, with a preliminary presentation and papal Mass, followed by an official exhibition the next day.

The painting was put on hold for a while new scaffolding was built. The second half of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings was completed quickly, and the completed piece was presented on the 31st of October 1512 and was displayed to the public the following day, All Saints’ Day. After the completion of the artwork, at the age of 37, Michelangelo’s renown grew to the point that he was referred to as il Divino.

Michelangelo was acknowledged as the finest artist of his day, elevating the stature of the arts itself, a distinction that endured for the remainder of his long life, and his Sistine Chapel artwork has always been ranked among the “paramount triumphs of pictorial art” ever then.

The Content of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Paintings

Michelangelo’s frescoes provide context for Botticelli and Perugino’s 15th-century epic cycles depicting the stories of Christ and Moses on the walls of the chapel. While the primary center scenes portray events from the Book of Genesis, there is much disagreement on the exact meaning of the thousands of individuals.

But while Michelangelo asserted he ultimately had a free hand in the artistic arrangement, Lorenzo Ghiberti made similar claims about his massive bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery, for which Ghiberti was restricted by provisions on how the Old Testament sequences should look and could only decide on the shapes and quantity of picture sectors.

It is probable that Michelangelo was allowed to determine the shapes and arrangement of the artwork, but the patron chose the topics and ideas.

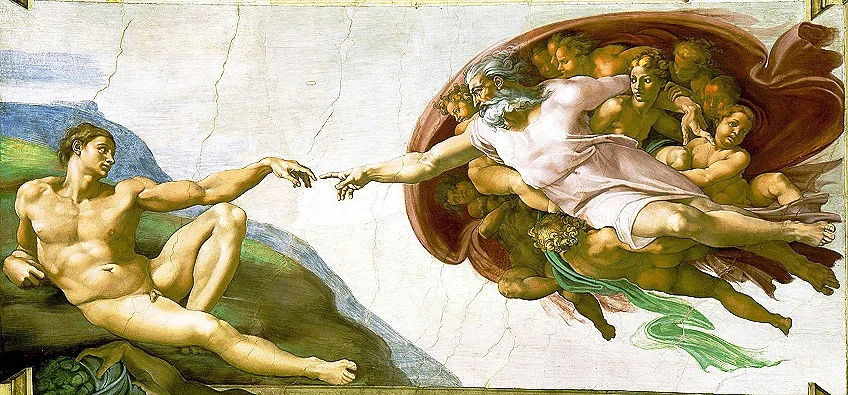

A figurative structural cornice delineates the center, virtually flat field of the overhead, which is split into four big rectangles and then again five smaller rectangles by five pairings of decorated struts that cut laterally across the core rectangular field. Michelangelo portrayed images from the Old Testament in these panels that appear to be open to the sky. The story starts at the chapel’s east end, with the first scenario above the altar, which is the focal point of the clergy’s Eucharistic celebrations. The Primal Act of Creation is shown on the little rectangular field just above the altar.

The Drunkenness of Noah is shown on the last of the nine central fields. Just above the cornice, are naked male youths, the purpose of which is unclear. They are close to the religious scenes in the topmost level, and unlike the individuals in the lower register, they are not stylized. They most likely depict the Florentine Neoplatonists’ vision of humanity’s perfect Platonic form, free of the stain of Original Sin, which all of the lower figures have.

“Their physical attractiveness is a symbol of heavenly excellence; their attentive and strong emotions are a manifestation of divine force,” stated Kenneth Clark. A lower register depicts an extension of the chapel’s walls as a trompe-l’oeil structural framing against which individuals press, with forceful modeling, beneath the painted cornice surrounding the center rectangular section. The characters are significantly foreshortened and greater in size than the characters in the core scenes, “producing a feeling of visual disequilibrium.”

The chapel’s four corners create a dual spandrel adorned with Old Testament redemptive sequences: The Crucifixion of Haman, Judith and Holofernes, The Brazen Serpent, and David and Goliath. Each one of the chapel’s opening arches penetrates into the curving vault, resulting in a triangle section of vaulting over each. Inside which sit enthroned Prophets who alternate with the Sibyls.

Seven visionaries from the Old Testament scriptures as well as five sibyls from Greek and Roman traditions were famous in Christian mythology, specifically for their predictions of the Messiah or the Nativity of Jesus. The lunettes just above windows, as well as the niches on every flank of each window, are decorated with depictions of Christ’s “distinctly human” Ancestors of Christ.

Interpretations of the Sistine Chapel Artworks

The ceiling’s obvious subject matter is the Christian belief in humanity’s necessity for redemption as supplied by God via Jesus. It’s a graphic representation of humanity’s need for a vow. Some specialists have also noticed less obvious subject matter, which they describe as hidden and banned. Tablets name Christ’s forebears and associated figures on the crescent moon-shaped spaces situated above each of the windows of the chapel.

A further eight sets of figures are displayed above them in the triangular spandrels, although they have not been associated with particular biblical figures. Four massive corner pendentives, each depicting a dramatic Biblical tale, round off the concept.

The narrative parts of the ceiling depict how God created the world as a flawless creation and then placed mankind in it, how humanity fell into dishonor and was condemned by death and estrangement from God. Humanity then fell deeper into sin and dishonor, and the Great Flood punished them.

God sent the savior of mankind, Jesus Christ, through a genealogy of ancestors stretching from Abraham to Joseph. Prophets of Sibyls and Israel which came from the Classical world foretold the arrival of the Savior. Historically, The Old Testament was formerly thought to be a foreshadowing of the New Testament. Many Old Testament occurrences and people were widely considered to have a direct symbolic relationship to some feature of Jesus’ life, an essential element of Christian philosophy, or a rite such as a Baptism or the Eucharist.

For instance, Jonah, represented on the ceiling by the large fish alongside him, is mentioned by Jesus in the gospels as being tied to his impending death and resurrection. Much of the iconography on the ceiling stems from the early church, yet it also has parts that indicate uniquely Renaissance philosophy that tried to integrate Christian doctrine with Renaissance humanism’s philosophy. The iconography of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel painting has been subjected to different readings in the past, some of which have been refuted by current research.

Others, such as the identification of the characters in the spandrels, remain a mystery. Modern academics have attempted, so far unsuccessfully, to identify a written basis for the ceiling’s religious purpose and have challenged whether or not it was totally designed by Michelangelo, who was both an enthusiastic student of the Scripture and regarded as a prodigy.

Method of Creation

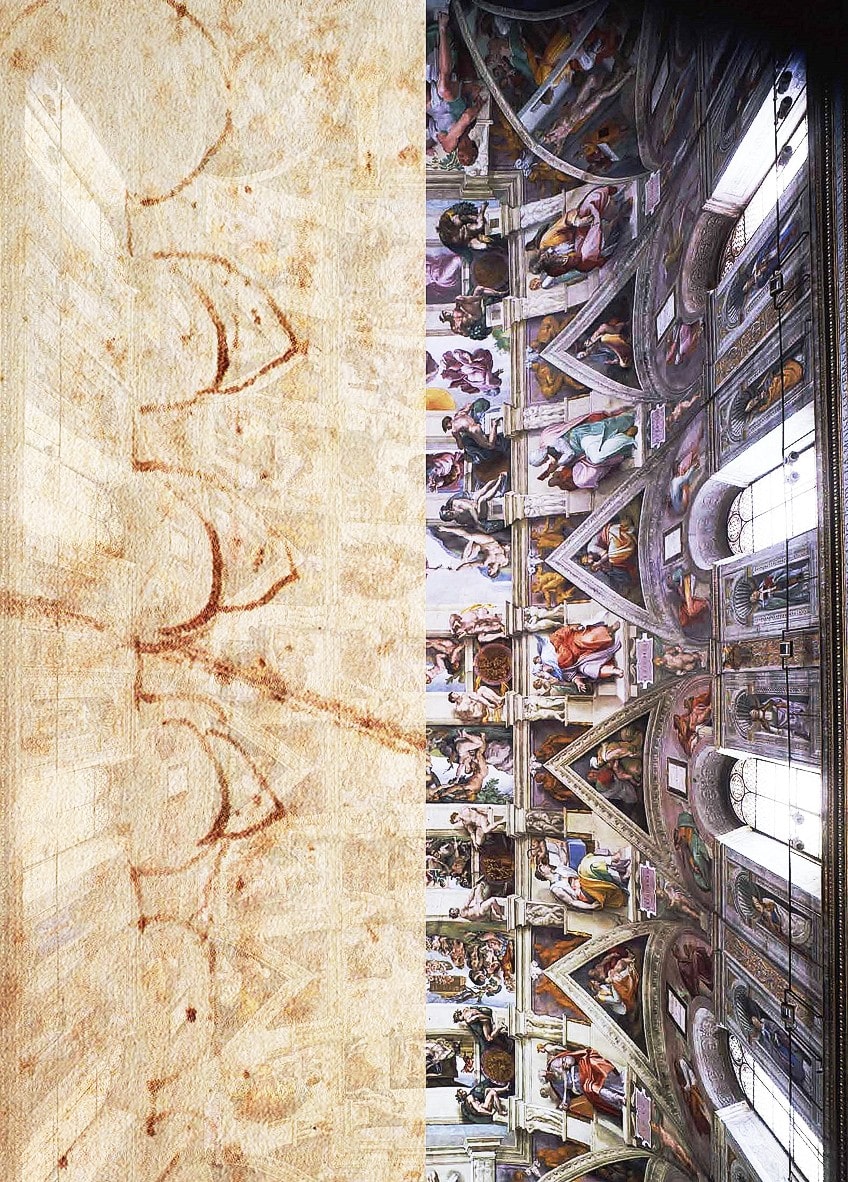

Michelangelo most likely started to work on the architectural ideas and drawings in April 1508. The ceiling’s preliminary work was completed in late July of the same year, and on the 4th of February 1510, Francesco Albertini noted that Michelangelo had “painted the top, arched section with extremely lovely images and gold.” According to Michelangelo’s manuscripts, the basic design was essentially completed in August 1510.

The chapel was used for clerical purposes throughout, except when the scaffolding construction required its closure, and interruption to the ceremonies was minimized by starting the work at the west end, farthest from the liturgical center all around the altar.

There is disagreement on the order in which the various sections of the ceiling were produced, as well as the arrangement of the scaffolding that enabled the painters to make contact with the ceiling.

Fabrizio Mancinelli, the restoration superintendent, speculates that Michelangelo may have only constructed scaffolding platforms in one half of the chamber at a time to save money on timber and enable light to travel through the uncovered windows. Condivi claims that the frame that held the steps and floors were all installed at the start of the project and that a lightweight screening, likely fabric, was strung underneath them to capture plaster dripping, dust, and paint spatter. The scaffolded parts of the wall remain as unpainted patches across the bottom of the lunettes.

In the most recent renovation, the holes were re-used to store scaffolding. The whole ceiling is frescoed, an old process of painting murals that depends on a chemical process between wet lime plaster and water-based colors to irreversibly bond the artwork into the walls. At the time, Michelangelo was an assistant in the studio of Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of the most capable and productive Florentine fresco artists, who was working on a fresco sequence at Santa Maria Novella and whose works were portrayed on the wall of the Sistine Chapel.

The construction began at the far end of the edifice, away from the altar, with the most recent narrative episodes, and continued towards the altar with the Creation sequences. The characters in the first three scenes in The Drunkenness of Noah are smaller than in the subsequent panels. This is due in part to the particular topic, which reckons with the future of mankind, but it is also due to Michelangelo’s underestimation of the ceiling’s magnitude. The Slaying of Goliath was also created in the early phases.

Michelangelo interrupted his efforts after completing the Creation of Eve near the marble screen that partitioned the chapel to transfer the framework to the opposite side. After seeing his finished work so far, he went back to work on the Temptation and Fall, succeeded by Adam’s Creation. Michelangelo’s manner broadened as the scope of the work increased; the final dramatic scenario of God in the process of creation was produced in a single day.

Illusionary Architectural Scheme

The initial element in the decorated architecture scheme defines the true architectural components by emphasizing the lines where spandrels and pendentives join with the curved vault. These were painted by Michelangelo as ornamental courses that resemble sculpted stone moldings. These feature two recurring themes, which is a typical formula in Classical architecture.

The acorn is a recurring theme in this chapel, representing the families of both Pope Sixtus IV, who erected the chapel, as well as Pope Julius II, who authorized the painter’s artwork.

The scallop shell is another theme, and it is one of the emblems of the Madonna, to whose Coronation the church was consecrated in 1483. The structure’s crown then extends above the spandrels to a highly projected decorated cornice that extends all the way around the overhead, dividing the pictorial regions of the scriptural episodes from the representations of visionaries, sibyls, and relatives who physically and metaphorically sustain the narrative.

Ten large painted travertine cross-ribs span the ceiling, dividing it into alternating wide and narrow pictorial sections, forming a grid that gives each figure a distinct location. A plethora of little figurines are intertwined with the painted building, their function appearing to be solely aesthetic. An assortment of medallions, or circular shields, may be found above the cornice and on each side of the lesser panels.

They are flanked by 20 more characters, known as ignudi, who are not part of the building but rest on plinths, their feet solidly set on the cornice. In terms of composition, the ignudi appear to inhabit a gap between the storytelling areas and the chapel’s own area.

Pictorial Scheme

Michelangelo portrayed nine episodes from the Book of Genesis, the Bible’s first book, along the middle area of the ceiling. The images are divided into three sets of three alternate large and tiny fields or picture panels each. The first set depicts Heaven and Earth’s creation by God. The next set depicts God producing Adam and Eve, the first male and female, as well as their transgression and banishment from paradise, where they had previously resided and communicated with God. The final set of three images depicts humanity’s misery, namely Noah’s family.

The images are not in chronological sequence. If they are regarded as three groups, the images in each of the three parts inform each other, just as they did in medieval artwork and stained glass. When read from the chapel’s entrance, the three portions of the creation, fall, and fate of humanity occur in opposite directions.

Each picture, though, is designed to be seen when facing toward the altar. This is difficult to see while seeing a replicated image of the ceiling, but it becomes visible when the spectator stares up at the vault. According to Radke and Paoletti, this reversed growth represents a return to a condition of grace.

Legacy

Michelangelo was the creative heir of Florence’s renowned 15th-century artists. Domenico Ghirlandaio, noted for his work on a couple of magnificent frescoes in the Tornabuoni Chapel and the Sassetti Chapel, as well as his involvement in the sequence of wall artworks of the Sistine Chapel, was his first teacher.

Michelangelo studied and took inspiration from the works of some of the most prominent Florentine fresco artists of the early Renaissance era, notably Giotto and possibly Masaccio, as a pupil.

Older portrayals of the origin scenes presented God as mainly static, a stationary, enthroned deity whose movement was signified by a hand motion, as in the formation scenes of Monreale Cathedral’s medieval Byzantine-style mosaics. Inspired by Dante Alighieri’s Paradiso, Michelangelo depicts God in full mobility, a departure from Giovanni di Paolo’s Creation.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling painting by Michelangelo is one of the most significant pieces of art in history. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel painting portrays various important biblical scenes from the Book of Genesis. The painting’s intricate tales and masterfully painted human figures astounded spectators when it was originally shown to the public in 1512, and it continues to dazzle the thousands of travelers and visitors from across the globe who tour the chapel day after day.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Sistine Chapel Painted?

In 1508, Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Julius was adamant that Rome be restored to its former splendor, and he had launched a ferocious drive to accomplish the lofty goal. The most noteworthy paintings in the church are Michelangelo’s murals on the ceiling and the west wall. Michelangelo created the paintings on the ceiling between 1508 and 1512.

How Long Did It Take to Paint the Sistine Chapel?

The Sistine Chapel art took Michelangelo a little more than four years to complete, from July 1508 to October 1512. Michelangelo had never produced frescoes before, and he was absorbing as he went. Furthermore, he opted to work in Buon fresco, the most challenging manner reserved for great masters. He also had to acquire some extremely difficult perspective methods, such as painting people on curving surfaces that appear correct when observed from over 60 feet below.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painting by Michelangelo.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. April 22, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/sistine-chapel-ceiling-painting-by-michelangelo/

Anthony, J. (2022, 22 April). Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painting by Michelangelo. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/sistine-chapel-ceiling-painting-by-michelangelo/

Anthony, Jordan. “Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painting by Michelangelo.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, April 22, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/sistine-chapel-ceiling-painting-by-michelangelo/.