“The Last Judgement” by Michelangelo – Inside the Sistine Chapel

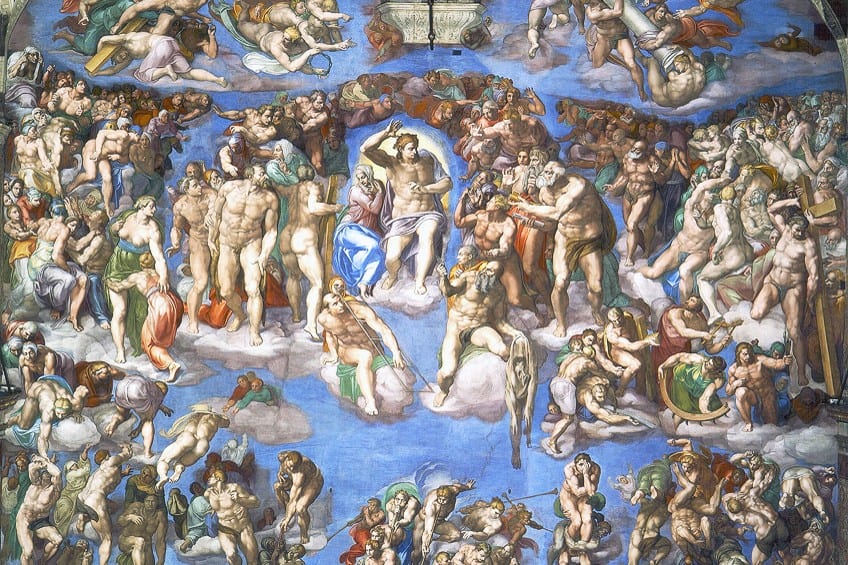

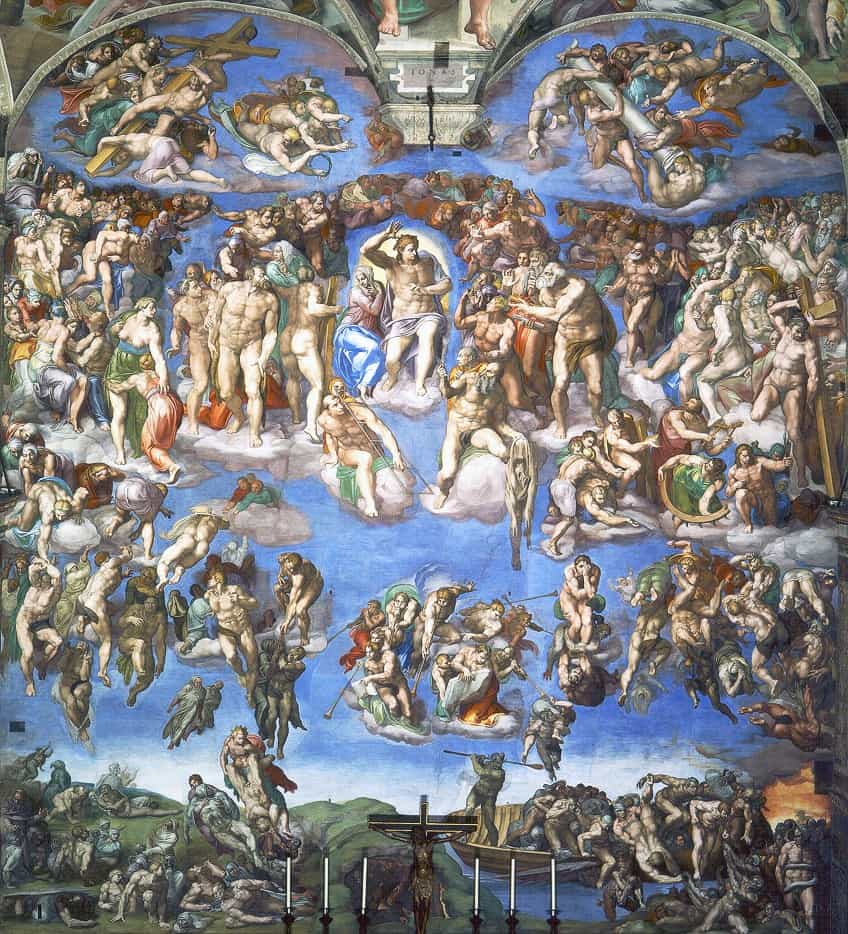

Who painted The Last Judgement painting in Sistine Chapel and why is it so highly revered? The Last Judgment painting was produced by Michelangelo, among the most highly-renowned artists of all of art history. The Last Judgement by Michelangelo portrays Christ’s return to Earth and the subsequent judgment of all the people who dwell on it. The Last Judgment painting covers the entire Altar of the Sistine Chapel and features 300 various angels and men.

Exploring The Last Judgement by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Date Completed | 1541 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (meters) | 13 x 12 |

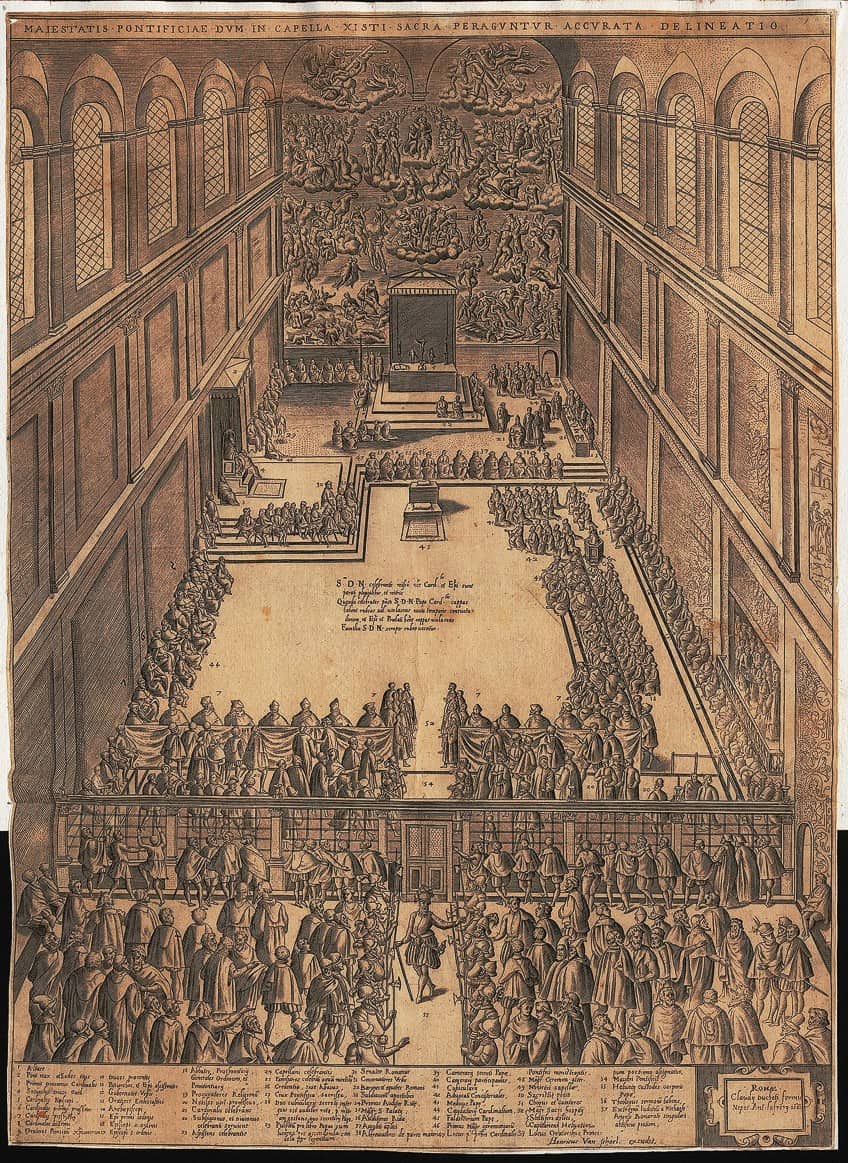

| Location | Sistine Chapel, Vatican City |

The Last Judgement painting was produced over the course of four years, starting in 1536, and was completed in 1541. The artist had completed the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling 25 years earlier. The Last Judgment painting was originally commissioned by Pope Clement VII, yet, was only completed under the Papacy of Pope Paul III, known for his stringent reformation views, which may have affected the content and appearance of the end result.

Compared to the earlier paintings on the Sistine Chapel’s walls, The Last Judgement painting appears rather monochromatic in its color palette, mostly dominated by sky and flesh tones.

However, after being cleaned and restored, more colors became apparent, such as yellow, blue, green, and orange. By the time Michelangelo completed the artwork, he was already 67 years of age. However, by that time he had already enjoyed a long and very successful career as an artist. Today, we shall start by taking a brief look at the artist behind The Last Judgment painting.

A Brief Introduction to Michelangelo

| Artist Name | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 6 March 1475 |

| Date of Death | 18 February 1564 |

| Place of Birth | Caprese, Republic of Florence, Italy |

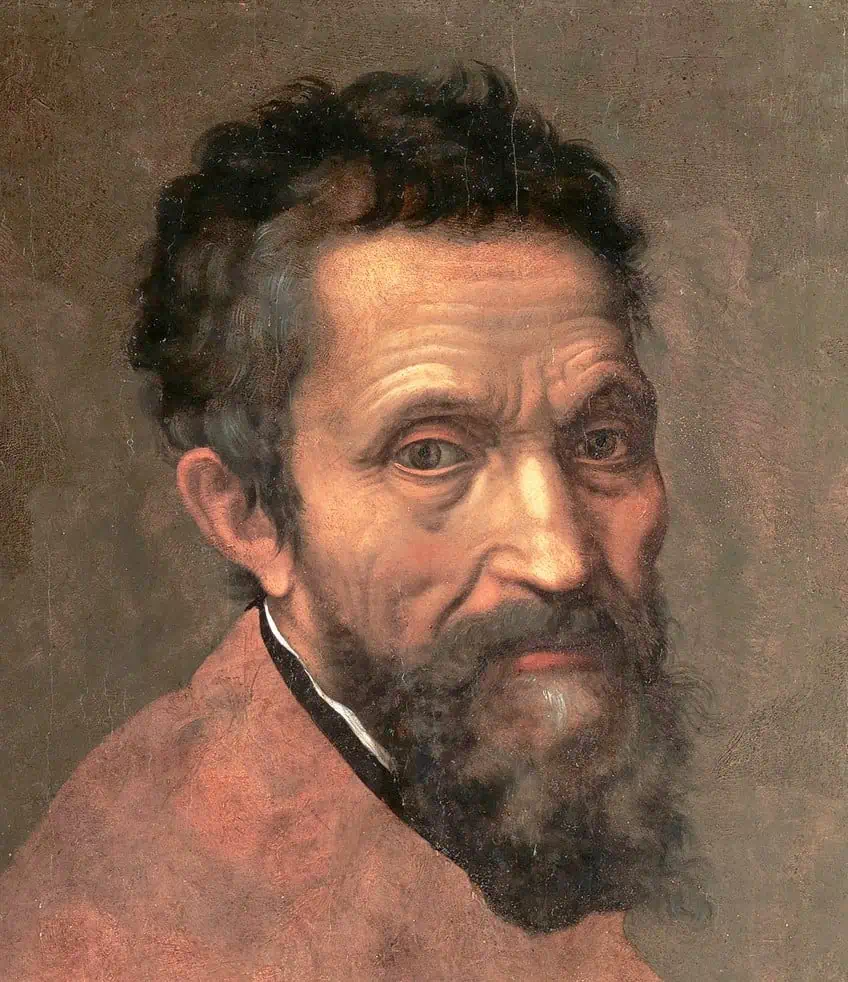

Born in Caprese, Tuscany, Michelangelo was a renowned sculptor, painter, architect, and poet. He had a long and successful career as an artist, with his famous David (1504) sculpture being produced when he was only in his late 20s. His fresco work on the Sistine Chapel’s ceilings is also regarded as some of the finest works from the era. Michelangelo’s architectural creations also left a permanent imprint on the world. Michelangelo’s design for the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica was finished after his passing, but it remains a tribute to his genius and ingenuity.

Michelangelo was well-known not just for his technical prowess, but also for his aesthetic vision and originality. His artworks embodied the Renaissance spirit and served to define it.

He was also noted for his work ethic, often spending long and hard hours on his work in hopes of achieving perfection. After the High Renaissance, a fleeting movement in Western art arose known as Mannerism from attempts by subsequent painters to emulate the expressive physicality of Michelangelo’s unique style.

History of The Last Judgment by Michelangelo

The Sistine Chapel project had been in the works for quite some time. It was presumably initially offered in 1533, but it did not appeal to Michelangelo at the time. A series of letters and other documents identify the initial subject as “Resurrection”, but it appears that this was always understood in the context of the Resurrection of the Dead, accompanied by the Last Judgment in Christian theology, as opposed to the Resurrection of Jesus. Some researchers argue that the more solemn final topic was substituted, reflecting the rising sentiment of the Counter-Reformation and that the surface of the wall to be covered was increased. Many of Michelangelo’s early 1530s sketches depict Jesus’ Resurrection.

Preparation

According to Vasari, the only contemporaneous source, Michelangelo originally envisioned painting the opposite end wall with a depiction of the Fall of the Rebel Angels. The wall’s preparation started in April of 1535, although painting did not begin for another year. Michelangelo directed that two small windows be filled in, three cornices are removed, and the surface be built forward as it ascends resulting in a single unbroken wall surface gently leaning forward by around 11 inches over the length of the fresco.

The preparation of the wall ended the artist’s 20-year friendship with Sebastiano del Piombo, who sought to convince Michelangelo and the Pope to complete the painting in his favored method of oil on plaster and who had succeeded in getting the smooth plaster surface required for this technique.

Issues

Because they had worked together almost 20 years before, it is believed that at this point the notion was proposed that Sebastiano would undertake the actual painting as per Michelangelo’s sketches. According to Vasari, after several months of inaction, Michelangelo grew infuriated and had the wall’s surface re-plastered in the rough Arriccio finish required as a foundation for the fresco. It was on this occasion that he infamously declared that oil painting was “an art for females and for lazy and indolent individuals like Fra Sebastiano”.

The creation of the new fresco necessitated the extensive destruction of several existing old artworks. Above the altar was an altarpiece by Pietro Perugino of the Assumption of Mary, for which a sketch exists at the Albertina, flanked by tapestries designed by Raphael; these, however, could simply be included elsewhere. Above this area, two works from the 15th-century Christ and Moses cycles occupied the middle region of the side walls.

Alterations

Above them was the first of a succession of standing popes in recesses, which included Saint Peter, in addition to Saint Paul, and a central depiction of Christ. Additionally, the undertaking necessitated the removal of two lunettes depicting Christ’s first two ancestors from Michelangelo’s original ceiling plan. Unfortunately, some of these paintings may have been destroyed by an incident in April 1525, when the altar curtains caught fire; the extent of the damage to the wall is unknown.

The chapel’s construction, erected in a rush in the 1470s, had caused problems from the outset, with regular cracks emerging.

A Swiss Guard died while approaching the chapel with the Pope on Christmas Eve in 1525 when the stone lintel of the entryway cracked and fell on him. The location is on sandy soil, which drains a broad area, and the previous “Great Chapel” experienced similar issues.

Choice of Subject Matter

The Last Judgment was a typical theme for huge church frescos, but it was rare to position it at the eastern end, above the altar. The usual location was on the western end, above the main doors at the rear of a chapel, so that when the congregation left, they carried this message of the consequences of their decisions home with them. It was often painted on the inside, as Giotto did in the Arena Chapel, or it could be sculpted on the outside as a tympanum. Nonetheless, a multitude of late medieval panel artworks, especially altarpieces, was themed around the subject and had comparable arrangements, although in horizontal image space. Altarpieces by Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling, Fra Angelico, and Hieronymus Bosch are among them.

Several features of Michelangelo’s composition are reminiscent of the well-established classic Western portrayal, yet with a fresh and unique perspective.

Most classic renditions place Christ in Majesty in roughly the same location as Michelangelo’s, and even bigger, with a bigger disproportion in scale compared to the other characters. Compositions, like this one, included a great number of figures, split between saints and angels around Christ at the top and the deceased being judged beneath. Normally, there is a stark contrast between the organized ranks of individuals at the top and the disordered and frenetic action below, particularly on the right side, which goes to Hell.

As the dead rise from their graves and walk towards judgment, the line of the judged commonly starts at the bottom left. Some of the risen pass judgment and ascend to become part of the group in heaven, while others cross to Christ’s left hand and subsequently descend to Hell at the lower right-hand corner. The condemned, and often the newly resurrected, are represented nude as a symbol of their humility as demons take them away, whereas angels as well as those in Heaven are fully clad, with clothes serving as a primary indication of the identities of groups and people.

Reception of The Last Judgement Painting

As soon as it was unveiled, the artwork caused controversy among Catholic Counter-Reformation detractors and admirers of the artist’s talent and the painting’s style. He was criticized for being oblivious to appropriate decorum, in regard to nudity and other parts of the painting, and for prioritizing artistic effect over respecting the scriptural narrative of the scene. Biagio da Cesena, the pope’s master of ceremonies, is quoted by Vasari as saying, “It was most shameful that in such a holy place there could have been illustrated all these naked people, revealing themselves so disgracefully, and that it was no piece for a papal chapel but instead for the taverns and public baths”, during a preview visit with Pope Paul III before the project was finished.

Religious Objections to The Last Judgement Painting

Cesena’s face was promptly included in the image by Michelangelo from memory as Minos, the ruler of the underworld including the donkey ears that symbolized foolishness, who has a coiling serpent covering his nudity. When Cesena protested to the Pope, it is believed that the pope made light of the situation, saying that because Hell was beyond his authority, the image would have to stay.

Others criticized Pope Paul III for commissioning and safeguarding the artwork, and he was under pressure to change, if not completely eliminate, The Last Judgment, which remained in place under his successor. Then, there were others who objected to the incorporation of characters from pagan mythology into portrayals of Christian subjects.

Apart from Minos and Charon and wingless angels, the highly classicized Christ seemed dubious: beardless Christs had vanished from Christian art, around 400 years before, yet Michelangelo’s depiction is indisputably Apollonian. Additional complaints were raised since the scriptural references were not followed. The angels sounding trumpets are all depicted in one group, although they have been sent to “the four corners of the earth” in the Book of Revelation.

Also, contrary to what Scripture says, he is not sitting on a throne. The wind is frequently shown in Michelangelo’s drapery; however, it was supposed that all weather would cease on the Day of Judgment. Gilio opposed the aesthetic techniques Michelangelo employed like foreshortening that confused or distracted unskilled observers, in addition to theological issues.

Marcello Venusti’s copy included the dove of the Holy Spirit above Christ, possibly in response to Gilio’s protest that Michelangelo should have represented the whole Trinity.

Revisions

“The images in the chapel should be covered over, and those in other churches should be removed, if they represent anything indecent or manifestly untrue”, a new directive declared bluntly. To respond to these criticisms and carry out the council’s decision, the genitalia in the painting was covered with drapery by the Mannerism artist Daniele da Volterra, most likely after Michelangelo’s death in 1564. Daniele was a “sincere and enthusiastic follower of Michelangelo” who limited his adjustments to a minimum and had to be instructed to return and add even more.

He also chipped away and recreated the majority of Saint Catherine, as well as the complete figure of Saint Blaise beyond her.

This was changed as in the original version, Blaise seemed to be staring at Catherine’s nude rear, and the posture of their bodies implied sexual intercourse to some onlookers. The repainted rendition depicts Blaise looking skyward, away from Saint Catherine. His work, which had begun in the top sections of the wall, was halted when Pope Pius IV passed in December 1565, and the church building had to be cleared of scaffolding for the burial and assembly to pick the next pope. El Greco had offered to redo the entire wall with a painting that was “respectable and acceptable, and no less skillfully executed than the other”. Apart from the two repainted figurines, almost 40 figures had draperies added to them.

These modifications were in “dry” fresco, making them easier to erase during the most extensive modern restoration (1990 to 1994) when roughly 15 of those added after 1600 were removed. It was chosen to leave the 16th-century modifications alone.

Contemporary Criticisms

Together with moral and theological critique, there was early significant criticism based only on aesthetic factors, which had not been observed at all in reaction to Michelangelo’s earlier Sistine Chapel ceiling. Lodovico Dolce, a prolific Venetian humanist, and Pietro Aretino were two significant contributors to the first wave of critique. Aretino had made a significant effort to get as close to Michelangelo as he had been with Titian, and yet he had always been rejected.

In 1545, his perseverance finally gave way, and he wrote a letter to Michelangelo about the artwork, which is now renowned as an illustration of insincere prudence and a letter authored with the intention to publish it.

Aretino’s remarks were based on one of the prints that had been swiftly produced despite the fact that he hadn’t actually seen the completed artwork in person. He claimed to speak for the common people in front of this new, larger audience. He claimed to speak for the common people in front of this new, larger audience. Yet, it seems that the uncensored form of the artwork was favored by the print-buying public because most prints featured this version long into the 17th century. Dolce followed it up with a published debate, L’Aretino, the year after Aretino passed, very probably in collaboration with his friend.

Many of the theologian critics’ arguments are reiterated, but this time in the name of decorum instead of religion, highlighting that the fresco’s specific and influential location made the quantity of nudity distasteful; a suitable assertion for Aretino, some of whose works were clearly pornographic but designed for a private audience. Dolce also criticizes that Michelangelo’s female figures are difficult to discern from male forms and that his models demonstrate “anatomical exhibitionism”, which many have echoed.

On these topics, a long-lasting rhetorical contrast between Raphael and Michelangelo arose, in which even Michelangelo’s admirers such as Vasari took part.

Modern Criticisms

In many ways, modern art historians and 16th-century authors debate the same characteristics of the fresco: the overall grouping of the individuals and portrayal of movement and space, the distinct portrayal of anatomy, the nudity and utilization of color, and occasionally the theological ramifications of the fresco. Bernadine Barnes, on the other hand, points out that no 16th-century critic shares Anthony Blunt’s perspective that: “This fresco is the work of a man who has been rattled out of his safe position, who is no longer at peace with the outside world and is unwilling to confront it squarely. He is no longer concerned with the outward beauty of the physical world”.

“It was admonished as the product of a pompous man at the time, and it was defended as a masterpiece that rendered celestial beings more beautiful than nature”, Barnes says.

Several other contemporary commentators share Blunt’s approach, highlighting Michelangelo’s “propensity away from the tangible toward the qualities of the spirit” in his latter decades. In Christianity, the Second Coming of Christ signified the end of time and space. Yet, Michelangelo’s peculiar rendering of space, in which the individuals inhabit different areas that cannot be successfully united, is regularly discussed. Apart from the issue of decency, the representation of anatomy has been much debated.

“Michelangelo has not attempted to resist that peculiar drive which compelled him to thicken a torso till it is virtually square”, Kenneth Clark writes of the Christ figure. “The wide repertoire of anatomies that Michelangelo envisioned for the Last Judgment seems sometimes to have been decided more by the necessities of aesthetics than by pressing needs of meaning, aiming not simply to delight but to overwhelm us with their impact,” S.J. Freedberg wrote. Frequently, the characters exhibit postures that are primarily ornamental”. He observes that the two frescoes in the Cappella Paolina, Michelangelo’s final paintings completed in November 1542, almost directly after the Last Judgment, show a significant shift in style, away from graceful and aesthetic effect and toward an exclusive consideration of conveying the narrative, with no due consideration for beauty.

The Last Judgment is recognized as a Renaissance art masterwork and one of Michelangelo’s finest works. It stands out for its powerful and dynamic arrangement, as well as its portrayal of human religious devotion and suffering. We can observe the dead rising as they are judged and either end up in hell or ascend to the heavens. Due to the controversial nature of the artwork, it has been at the center of debate since before it was even fully completed. However, today, it is recognized for the Renaissance masterpiece that it truly is.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Does The Last Judgment Painting Depict?

One of the most distinctive The Last Judgement painting techniques is that the picture is separated into two halves. Christ is represented in the upper portion, in the center, flanked by the Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, as well as several angels. The blessed are seen rising to heaven to Christ’s right, while the condemned are shown being hurled into hell to his left. The dead are portrayed emerging from the grave and being sentenced by Christ in the artwork’s lower part. The blessed’s souls are escorted to paradise by angels, while the damned’s souls are pulled into the fiery furnace by demons.

What Were the Controversies Surrounding The Last Judgement Painting?

While The Last Judgement painting techniques were admired, there were many people who felt that the depiction was too pornographic for the setting in which it was produced. People complained about the naked figures, which were said to suit public bathrooms and taverns better than a place of worship. Others also did not appreciate the blending of Christian and pagan characters. The layout of the individuals also sparked debate, as everything after the Judgment is meant to be represented as one, with no separation of time and space. Jesus is also portrayed as being without a beard, which was unusual for its time.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, ““The Last Judgement” by Michelangelo – Inside the Sistine Chapel.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. June 12, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/the-last-judgement-by-michelangelo/

Anthony, J. (2023, 12 June). “The Last Judgement” by Michelangelo – Inside the Sistine Chapel. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-last-judgement-by-michelangelo/

Anthony, Jordan. ““The Last Judgement” by Michelangelo – Inside the Sistine Chapel.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, June 12, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-last-judgement-by-michelangelo/.