Pre-Raphaelite Art – Explore the History of the Pre-Raphaelites

The pre-Raphaelites rebelled against the sway of the British Royal Academy, which supported a constrained spectrum of idealistic or moral topics and traditional standards of beauty derived from the early Italian Renaissance. On the contrary, the pre-Raphaelite painters drew their inspiration from a previous era, i.e., the centuries that came before the High Renaissance. The pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood thought that artists before the Renaissance presented a model for representing nature and the human form realistically instead of aspirationally and that the collaborative guilds of Middle Ages craftsmen provided a different perspective of the artistic congregation to initiatives adopted by mid-19th-century academics.

Exploring the History of Pre-Raphaelite Artwork

The group that identified themselves as the pre-Raphaelites opposed the British Royal Academy’s teaching strategies, as well as its penchant for Victorian topics and styles. This was because they believed that truth and experience had been supplanted by rote learning.

They were one of the earliest notable critiques of “formal” art, and their early “institutional critique” played a crucial role in the growth of modern art in Britain.

Romanticism Roots

In early 19th-century Britain, numerous major events connected to Romanticism gave rise to the pre-Raphaelite Movement. The first was a response to industrialization, which began to take off in earnest in the late 18th century and by the 1830s had become Britain by far the most technically and technologically sophisticated country in the world. But as cities grew, there was also a rise in crime as a result of the inflow of workers from the countryside who were forced to live and work in filthy, polluted, and unhygienic circumstances.

Romantic critics looked for methods to reveal these shifts and make things better because government regulation had fallen behind these quick developments.

Designers and artists like Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, who was in control of all the interior decoration of the most recent Houses of Parliament, espoused a come back to the Gothic aesthetic and the allegedly better and healthier, ethical environment of the Middle Ages, which they saw as the complete opposite of the industrial age.

Particularly among the orthodox Royal Academy, the Italian High Renaissance had popularity in the British art community. Joshua Reynolds, a painter who was a huge enthusiast of the High Renaissance and in particular the Italian Raphael, founded the Royal Academy in 1768. The Grand Manner, or idealizing subjects in the attire and classical settings evocative of ancient Greece and Rome, was favored by the Royal Academy, which promoted genre and portrait art.

The Grand Manner and classical values were opposed by the Romantic movement, which placed a strong focus on the landscape.

In order to divert attention from unpleasant cityscapes, the artwork of Thomas Gainsborough, John Constable, and J.M.W. Turner also proven to be quite successful. The Romantics painted a nostalgic picture of rural life, farming, and the humbling influence of nature on the human form. Edmund Burke coined the expression “the sublime,” which suggests that a sublime piece of art would indeed be able to elicit the spectator’s complete spectrum of emotions. Many of these creations were connected to this idea.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The closely guarded pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in September 1848 by a collective of youthful revolutionary thinkers, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt. They were motivated by these early Renaissance artworks and frustrated by the prescriptive and idealistic approach to art adopted by the Royal Academy.

They sought to do three things: reinvigorate British art; make it as dynamic, forceful, and innovative as the early Renaissance pieces produced before the Italian artist Raphael; and discover ways to represent both nature and genuine emotions in art.

The phrase “Pre-Raphaelitism” began to apply to any artwork created in the manner made famous by the original trio, even if the movement’s inspiration and notoriety resided with the original three founders. Ruskin’s observations on “imaginative” contemporary artists who can “note the precise and characteristic leaf, bloom, seed, fracture, color, and interior anatomy of everything” also served as inspiration for the pre-Raphaelites.

Nothing that the creative painter dares not do—or does not permit the need of doing—is within the bounds of natural possibility. He is not constrained by the natural rules he is aware of.

Ruskin said that the pre-Raphaelite painters “will create either what they perceive, or what they presume might have been the real truths of the picture they wished to portray, regardless of any conventions of picture-making” in an 1851 message to the London Times, which defined the beginning of his participation with the collective.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Split

In addition to helping Ruskin withdraw his support, Millais personally contributed to the Brotherhood’s dissolution through his own efforts. Christ at the House of His Parents, a new painting by Millais that was displayed in 1850, garnered criticism for blaspheming the Virgin Mary from a variety of quarters, including novelist Charles Dickens. Critics called Mary, whom Millais based on his sister-in-law, “ugly,” implying that it was immoral to show her as anything less than an idealized, beautiful lady and to display the Holy Family as common and underprivileged.

Following this dispute, James Collinson departed the group, but the remaining members remained undecided and abstained from further joint public performances.

After this, the Brotherhood was officially dissolved in 1853 when Woolner relocated to Australia and Millais obtained membership into the Royal Academy, the very organization that the Brotherhood had been criticizing before.

Even though the original Brotherhood only existed for around five years, the word “pre-Raphaelite” persisted and was widely used in Britain for many years.

The Lead to the Arts and Crafts Movement

Dante Gabriel Rossetti met Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, two of his young disciples, in 1857 in Oxford. Rossetti hired Burne-Jones as his assistant, and he asked the two friends to assist him in painting scenes from King Arthur’s life on the Oxford University Union’s ceiling. Together, the three men preached a pre-Raphaelitism that was even more adamantly medievalist and extolled the merits of a pre-industrial lifestyle while producing paintings and furniture in the manner of late medieval art.

Morris and Burne-Jones started to develop new ideas for the pre-Raphaelite movement along with Rossetti.

Morris, in particular, was eager to expand the pre-Raphaelite philosophy’s application to disciplines other than fine art, and he ultimately formed the Arts and Crafts movement. Morris formed a brand-new design company named Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company with Burne-Jones, Rossetti, and a few other collaborators. The business specialized in making stained glass, wallpaper, furniture, textiles, and other items using traditional handicraft techniques from the Middle Ages with imagery from Symbolist literature and poetry.

Later, Morris acquired his other partners, and in 1875, he changed the company’s name to Morris & Co. The 1880s and 1890s saw the company flourish, but it finally went out of business in 1940.

After the Brotherhood

More artists started to link with Pre-Raphaelitism during the following two or three decades. While many were painters, the movement also benefited from the inventiveness of sculptors and photographers. One of the artists who chose not to formally join the Brotherhood while maintaining a strong relationship with its members was Ford Madox Brown.

He shared the Brotherhood’s enthusiasm for Naturalism, literature, and poetry, but he stood out from the other painters because of his overt criticism of Victorian society.

He assisted in the establishment of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., and his child Lucy, who was also an artist, wedded William Michael Rossetti. While the artist Arthur Hughes had gotten to know Millais and Hunt during the early Brotherhood years, he was not formally a part of the group until he helped with the Oxford Union paintings. In reality, Hughes’s work serves as the best example of the “Arthurian” school of Pre-Raphaelitism, which specialized in the myths and legends of medieval England.

Recent shows have looked at the connection between early British fine art photography and Pre-Raphaelitism. The pre-Raphaelites had an impact on photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron, Roger Fenton, and Henry Peach Robinson. These pioneers pushed the fine arts and artwork with the mechanical reproduction of nature in the camera. In addition to drawing influence from the same literature, medievalism in dress and decorating, and a focus on presenting light and natural detail, the painters and photographers were frequently friends and shared a love of art.

Portraits of women became more prevalent as the pre-Raphaelite group grew. Artists like Madox Brown, Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti started depicting attractive, frequently sexually powerful women starting in the late 1860s.

Most of the models they selected were unconventional in terms of appearance compared to Victorian standards. The models who were also artists were Marie Spartali-Stilman, Georgiana Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s preferred model, Jane Morris, the spouse of William Morris and a superb embroiderer.

Pre-Raphaelitism Concepts

The utmost level of objectivity in their representations of nature was one of the first pre-Raphaelite ideals. For example, Millais and Hunt spent a significant amount of time away from London in the country, painstakingly researching flora and flowers to create their paintings. The inclination for an unadorned, genuine aesthetic added realism to the legendary stories that their listeners were already accustomed to.

For instance, British academic painting might reduce details like St. Anne’s severely bloated and old hands in Millais’ Christ in the House of his Parents, in order to appease the general audience.

Medievalism

Morris, Rossetti, and Burne-Jones, who also explored the stories of medieval England, expanded the fascination with late medieval and early Renaissance paintings from northern Europe and Italy. They were drawn to medieval workmanship in part because of John Ruskin’s impassioned argument that the independent inventiveness of medieval artisans was better than the “slavery” engendered by the contemporary industrial system. William Morris was profoundly influenced by his argument, and he embarked on an idealistic quest to restore pre-industrial ideals and practices to society.

The utilization of labor-intensive handcrafts and a reversion to natural materials and colors were two things Morris’ business notably stressed.

Decorative Arts

Pre-Raphaelitism had a significant impact on the decorative arts while being more frequently identified with painting. The Arts and Crafts movement was finally founded, and William Morris was at the vanguard of the design revolution that brought about that movement. The goal of Morris’ business, Morris & Co., was to open out good design to a larger audience.

Morris was assisted by other painters, including Burne-Jones and Dante Rossetti, who created patterns and embellishments for tapestries and furniture.

A group of illustrators, like Phoebe Traquair and the well-known Aubrey Beardsley, were also influenced by the pre-Raphaelite movement. Pre-Raphaelitism and other kindred movements were combined in their hybrid styles. For example, when Traquair drew the illustrations for the renowned Sonnets from the Portuguese, by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, she merged the look of a medieval illuminated manuscript with watercolor artworks on vellum and decorative elements taken from European manuscripts from the 14th century.

Traquair’s illuminations show her interest in Celtic and Byzantine arts, even though she had been strongly affected by the literature of the pre-Raphaelites.

Famous Pre-Raphaelite Paintings

Pre-Raphaelite artwork emphasized Naturalism above all else: the artist’s careful observation of nature and adherence to its appearance, even when doing so carried the danger of revealing ugliness. A fondness for natural forms was also mentioned as the foundation for patterns and ornamentation that served as a counterbalance to the industrial designs of the industrial period. As a reaction to the negative impacts of industrialization, the pre-Raphaelites used the medieval period as a point of stylistic comparison and as a model for the fusion of art and life in the pragmatic arts.

Their restoration of medieval aesthetics, narratives, and manufacturing techniques had a significant impact on the growth of the Arts and Craft movement.

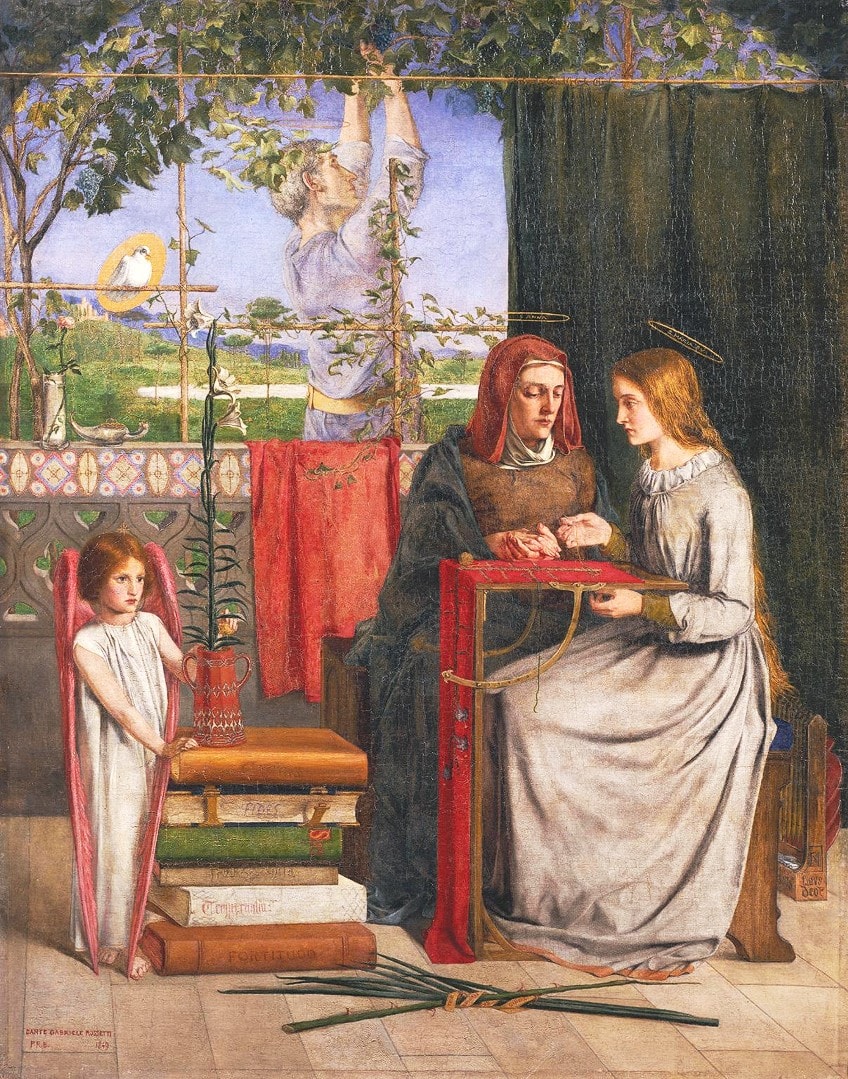

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

| Artist | Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882) |

| Date Completed | 1949 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Collection of the Tate Museum |

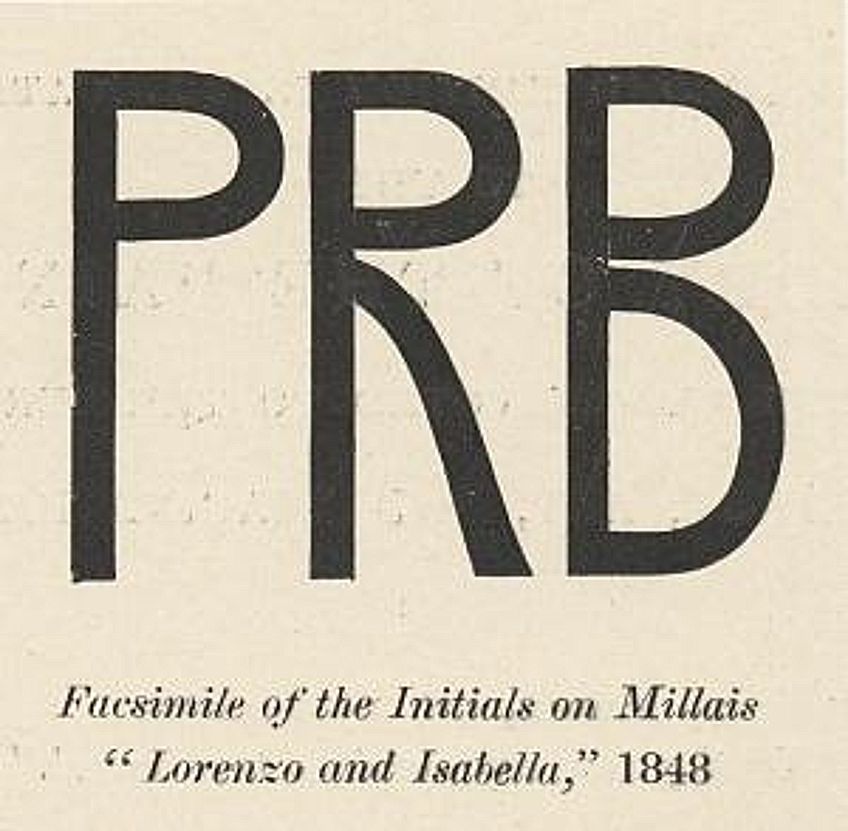

Pre-Raphaelite painter Rossetti’s picture was the first pre-Raphaelite piece to be exhibited in public. It had the cryptic initials “PRB,” signifying that the creator belonged to the recently formed pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Early Renaissance and late Medieval paintings, which at the time were extremely disliked in Victorian England, are specifically referenced in the style.

The foreground and backdrop are noticeably flat, defying typical perspective techniques, which foreshadow following artists’ rejection of traditional methods of rendering realistic space.

According to art critic Jason Rosenfeld, “Rossetti’s image displays a revivalist style that relies on early Renaissance works from Northern Europe and Italy, coupled with a complete religious iconography conveyed in an abundance of well-observed details and natural shapes, such as the flowers evocative of the Virgin Mary’s purity and the candle invoking piety.”

Rossetti adds a further layer of reality by depicting his sister and mother in the roles of Mary and Saint Anne.

At that time, this was seen as heretical due to the usual reliance on classical models for the Holy Family. Rossetti’s boldness and Medievalist aesthetic caused a lot of controversies and highlighted the limitations of the “Grand Manner,” which was nonetheless praised by the British Academy.

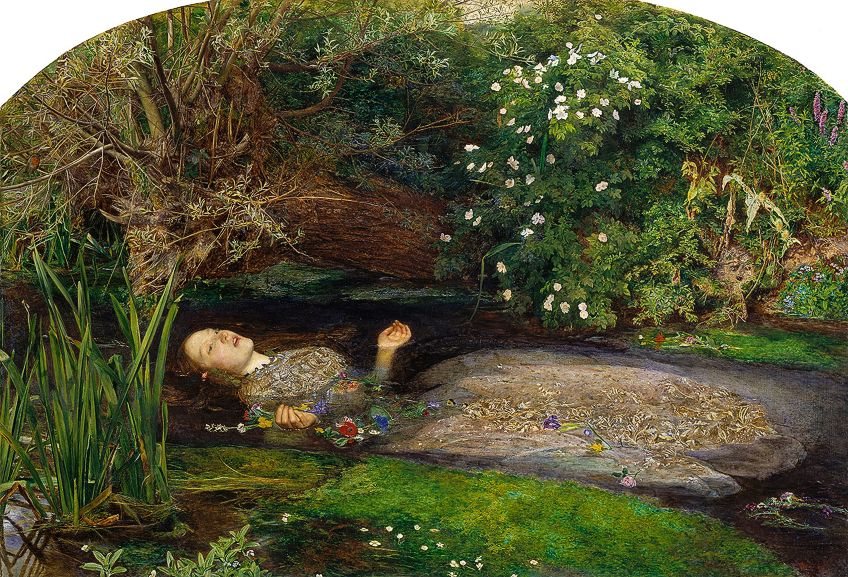

Ophelia (1851) by John Everett Millais

| Artist | John Everett Millais (1829 – 1896) |

| Date Completed | 1852 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Collection of the Tate Museum |

Ophelia is undoubtedly both John Everett Millais’ greatest work and the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s most recognizable piece of art. Millais spent months painting this piece in the countryside when he was only 22 years old, painstakingly creating the background.

Millais also incorporated the muddy bank, reeds, and a water rat in addition to the flowers and boughs.

The figure of Ophelia, whose demise is detailed by Queen Gertrude in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, was patterned by Elizabeth Siddall, the daughter of a cutlery maker, whose distinctive appearance was highly valued by pre-Raphaelite artists. Ophelia sings as she slowly slips into the river after going insane after Hamlet’s rejection.

To effectively depict the impact of water on her clothing and hair, Millais had his subject stand in a bathtub filled with water.

The model famously came close to passing away when the candles heating the water went out and she developed pneumonia. In Ophelia, Millais went far beyond prior Victorian genre paintings by attempting to accurately portray a scene from a fictitious work in a way that is both romantic and tragic.

Our English Coasts (1852) by William Holman Hunt

| Artist | William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910) |

| Date Completed | 1852 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Collection of the Tate Museum |

Hunt painted a large portion of this image outside, on the cliffs close to Hastings, as landscape painting was a significant pre-Raphaelite statement of their love for nature. This pastoral painting was praised for its naturalism: Hunt devoted special attention to the exact shifting effects of light on a variety of surfaces (field, flowers, wool, water, sky), all of which would have appeared quite contemporary to the Royal Academy when it was first presented in 1853.

This pastoral artwork was hailed for its realism.

The asymmetrical composition ensnares the lost sheep in a disorganized tangle of coastal flora, marking a daring departure from idealized images of the English countryside. Additionally, the image had profound political importance. Southern England’s cliffs point toward France and suggest that another country may invade.

Hunt’s unattended sheep, placed dangerously on the cliff’s edge, may have symbolized the vulnerability of the British countryside and her coasts to a people alarmed about Napoleon III’s coup d’état in 1851.

With the sheep’s emotions, Hunt underlines this political interpretation of the environment even more; their endearing uniqueness piques the viewer’s interest in both their destiny and the fate of England. Hunt altered the painting’s title to Strayed Sheep before it was displayed at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855, probably to allow for more unbiased interpretations.

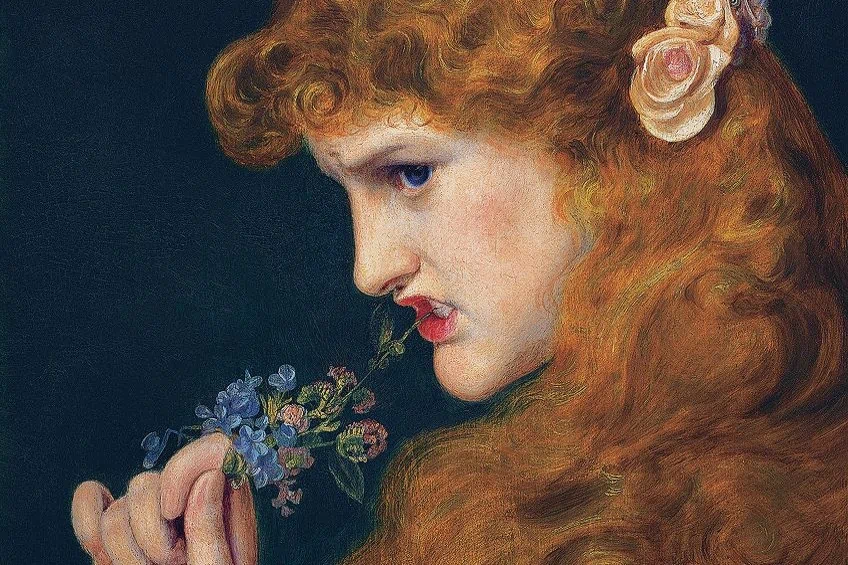

Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die (1867) by Julia Margaret Cameron

| Artist | Julia Margaret Cameron (1815 – 1879) |

| Date Completed | 1867 |

| Medium | Carbon Print Photograph |

| Current Location | Victoria and Albert Museum |

One of the many photographers influenced by the pre-Raphaelites was Julia Margaret Cameron. The new medium of photography gave Cameron enormous flexibility to explore in her home studio and with her friends and family, despite certain limitations she faced as a working woman. She worked on a collection of close-up pictures of heads and faces, frequently those of ladies in her family, in the middle of the 1860s. Her personal assistant, Mary Hillier, is seen in this picture.

Cameron shows Mary as a sensuous and liberated subject with the trademark split lips and flowing hair of the pre-Raphaelites, rejecting the constraints of rigid, formal Victorian photography.

She is depicted against a plain background with simple attire, avoiding any telling narrative aspects in favor of an emotional focal point. Additionally, in keeping with the literary sensibility of the genre, the title of the film relates to a phrase spoken by Eleanor, one of Lord Alfred Tennyson’s sorrowful heroines who died of forbidden desire for Sir Lancelot. In contrast to most photography at the time, Cameron considered the work as a rejection of “simple traditional topographic photography – map-making and skeletal depiction of feature and shape.”

Instead, she thought that photography might be used as an independent art form, an uncommon development that ties to the pre-Raphaelites’ advances in other non-fine arts mediums.

Laus Veneris (1878) by Edward Burne-Jones

| Artist | Edward Burne-Jones (1833 – 1898) |

| Date Completed | 1878 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Laing Art Gallery |

The German legend of Tannhauser, which tells the tale of a warrior who is adopted by Venus, the Roman goddess of love, and pushed to lead a life of sexual excess, serves as the inspiration for the painting’s subject. In the end, Tannhauser decides to change his ways after realizing his mistake. In Laus Veneris, Burne-Jones depicts a scenario of Venus unwinding with her handmaidens in her opulent bower.

The setting is subtly seductive. This piece is “one of the most audacious and powerful works in the pre-Raphaelite canon,” according to pre-Raphaelite historian Tim Barringer.

Burne-Jones blurred the lines between the fine and decorative arts in this piece and provided a nuanced reflection on how music, art, and love are related. The artwork’s flat plane, swipes of vivid color, and numerous compositional elements create a highly ornamental surface.

The picture itself has the sense of a tapestry.

The Aesthetic movement, which gained popularity in the 1880s, was inspired by this emphasis on an aesthetically appealing and harmonious arrangement. Laus Veneris shares several similarities with the poem of the same name written by Algernon Swinburne and included in a book devoted to Burne-Jones.

Kelmscott Manor Bed Hangings (1893) by May Morris

| Artist | May Morris (1864 – 1938) |

| Date Completed | 1893 |

| Medium | Cotton, embroidery |

| Current Location | Kelmscott Manor |

Morris and Rossetti co-rented Kelmscott Manor, an Elizabethan home in the countryside, in 1871. Morris viewed it as a location where he could live in accordance with nature and pursue his passions in art and society. He liked his beautiful four-poster bed so much that he composed a poem about it. It was in the house. May, the embroidery department manager of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., was a gifted seamstress, and businesswoman. For her father’s bed, she made hangings that she embroidered with passages from Morris’ poem.

The end product is a singular synthesis of poetry, creative design, and expert craftsmanship that perfectly captures her father’s all-encompassing conception of Pre-Raphaelitism and what constitutes a finished artwork.

According to Tate curator Alison Smith, “May was one of the premier craftspeople of the age, having acquired a talent for stitching from her girlhood and augmented by learning the skill at the South Kensington School of Design.”

May created her own distinctive stitching technique, influenced by her father’s love of nature and done with a freer hand and less strict design.

The bed and its hangings, like other pre-Raphaelite furniture, were created to be both works of art and useful pieces of furniture. In 1893, the hangings were on show as part of an arts and crafts production exhibition in a London gallery, demonstrating the late pre-Raphaelite movement’s ambition to infuse art and beauty into every aspect of life.

That concludes our exploration of pre-Raphaelite artwork and pre-Raphaelite painters. pre-Raphaelites’ paintings expressed a desire for a broader connection between art and literature. The group aimed for a return to the rich detail, vibrant colors, and intricate compositions of Italian art from the Quattrocento period. They disapproved of what they saw to be the mechanical methodology that Mannerist artists Raphael and Michelangelo’s successors had originally used.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Pre-Raphaelite Artwork?

In the Victorian era, a group of artists called themselves the pre-Raphaelites. They held the opinion that art should reflect reality as closely as possible. Consider it in this way. If you painted a park, it should depict the park exactly as you perceive it. Therefore, since you know the grass is green, you cannot paint it blue.

Who Was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood?

A collective of English painters, poets, and critics of art called themselves the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Raphael’s unique classical attitudes and magnificent compositions, according to the Brotherhood, had a corrupting impact on academic painting education. The group related their works to that of English writer John Ruskin, whose religious background inspired him.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Pre-Raphaelite Art – Explore the History of the Pre-Raphaelites.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 3, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/pre-raphaelite-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 3 August). Pre-Raphaelite Art – Explore the History of the Pre-Raphaelites. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/pre-raphaelite-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Pre-Raphaelite Art – Explore the History of the Pre-Raphaelites.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 3, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/pre-raphaelite-art/.