Babylonian Art – Introducing the Art of Ancient Mesopotamia

The ancient city of Babylon was once considered among the oldest cities in present-day Iraq and was also included in the conquest plans of Alexander the Great, right before he died in 323 BCE. Babylonian art drew from local mythology, which influenced the creation of many relief sculptures that emphasized the piety of the city’s rulers and even featured goddesses who were portrayed in designs across Babylonian jewelry and sculpture. In this article, we will delve into the fascinating history of Babylonian art, including looking at a few interesting paintings, art styles, sculptures, and artifacts that give us a glimpse into the history and culture of the Babylonians.

Contents

An Introduction to Babylonian Art and Culture

Where was ancient Babylon, and what is known about the ancient city today? When studying the history of Babylon, one needs to have an idea of the civilization’s defining contributions in the broader historical context. Ancient Babylon was a city located in Southern Mesopotamia along the Euphrates River, in current-day Iraq. While not much is known about the origin of the city, scholars have recognized that local Mesopotamian mythology identified the patron God Marduk to be the creator of the world who first laid the foundations of Babylon.

The city of Babylon is also referenced several times in the Bible and draws reference to prophetic warnings, the Tower of Babel, and the deportation of many Israelites under the rulership of King Nebuchadnezzar II. One of the few surviving records of the city of Babylon is a document from the late 3rd Millennium BCE, which stipulated that the royal city was ruled by King Hammurabi who established control over surrounding kingdoms. His control and power reach were seen throughout the Persian Gulf, all the way to Syria.

Babylonian culture was reliant on the mythology and symbolic teachings from the old society of King Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar I, which saw the introduction of hybrid cosmic beings and mention of supernatural creatures. Hierarchy and religion were also major governing factors that Babylonians used to define their social and cultural practices.

Celebrations such as New Year would include elaborate processions with Babylonian statues on parade as followers march to the temples to honor the gods and goddesses that later inspired Neo Babylon.

The Kassite Period

By 1500 BCE, Babylon was overruled by a dynasty of Kassite kings who unified the region into the kingdom of Babylonia. At the time, the Babylonian cities became hubs of scholarly learning, resulting in many texts on divination, medicine, astrology, and mathematics. Leaders of this time period were also in contact with Egyptian pharaohs as indicated in the cuneiform letters discovered at Amarna. Babylon was also known for its conflicts with Assyria as well as the production of one of the world’s most famous maps.

After 1595 BCE, Babylon saw a change in leadership, which was previously dominated by King Hammurabi’s successors. The passing of the Old Babylonian period brought a new dynasty where non-Babylonian rulers took charge. These rulers were known as the Kassites, who quickly adopted the pre-existing Babylonian styles and conventions in royal iconography. Special stone monuments called kudurru were released during this time and were physical markers of land that were granted by the king to high-ranking officials. These monuments were inscribed with texts and imagery related to specific Gods, animals, and other symbols as a form of protecting the inscriptions.

The Kassite period also saw the creation of cylinder seals with detailed inscriptions concerning the king and a goddess named Lama, who was portrayed in prayer positions and was believed to pray on behalf of a human donor to a powerful deity.

King Nebuchadnezzar II

Around 612 BCE, Babylon was expanded and redeveloped under King Nebuchadnezzar II and Nabopolassar, which saw the 6th century BCE Babylon flourish as the largest civilization in ancient Mesopotamia. King Nebuchadnezzar II’s name was derived from a previous king who recovered the Babylonian statue of Marduk from Susa, which made his name not only important but also revered and respected. King Nebuchadnezzar II went on to establish the Hanging Gardens as well as many religious structures, palaces, the Ishtar Gate, and Ziggurat tower, city walls, and glazed-brick relief sculptures of roaring lions, which contributed to the reinstatement of Babylon as a “cosmopolitan” city.

The city of Babylon was no doubt a pool of inspiration where ideas around mathematics, the prediction of the future, and dragons. The poets, artists, and scholars of Babylon also documented their work on a writing system known as cuneiform, which was created on tablets of stone and clay. Engineers of ancient Babylon also invented many intriguing theories and mechanics to measure the passage of time. The most well-known mathematical system used in Babylonian society was “60”, which is the span of time division we see in our clocks and watches and was first adopted by Babylonians.

Over time, the system was adapted and molded by the Greeks into the division and understanding of time we know today.

Art Materials in Babylonia

The art of ancient Babylon was determined by the materials that were available to the artists of the time. Construction materials such as mud and clay were abundant, however, stone was much more challenging to come by. Large trees were also difficult to source to improve construction, however, despite the limited supply of materials, artists were able to mimic Sumerian methods to create bricks and thus build many grand palaces with roofed vaults and arches.

Material such as adobe, or mud bricks, were used to construct thick walls and terraces with ceramic embossing crafted from pieces of stone or baked clay. Black diorite was also used to create kudurrus, which were used to define a property’s boundaries. Alabaster was also sourced from the River Tigris for decorative use in important buildings.

Divination and the Ziggurat

The ancient Babylonians were also obsessed with the art of divination and cultivating the ability to predict the future. As such, various Babylon artifacts with cuneiform were created to teach such methods and reveal “ominous signs”. Later on, people moved to the stars and dreams as tools for divination. The Babylonians were also credited with the zodiac sign system, whereby many inscriptions and drawings of the zodiac were found on monuments, which later evolved into the idea of horoscopes.

The Tower of Babel was another source of inspiration for many artists over the ages to convey religious and mythological themes.

The Tower of Babel was known to be a real structure that existed in the capital of Babylon and was called the Ziggurat. The Old Testament of the Bible states that the tower was built to reach the heavens” and was more so a symbol of human ambition. It also stated that this was a time when the whole world shared a single language. According to researchers, the building was estimated to have towered up to 17 meters tall. Artists such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder were also inspired to paint a series on the Ziggurat and the biblical narrative in the 16th century.

The Neo Babylonian Empire and Architecture

From 539 BCE, the Neo Babylonian Empire took flight after the city was conquered by Cyrus II of Persia, who was intent on rebuilding a new empire emanating from Iran. Neo Babylonia was an independent city-state, which saw a period of return to art styles from the 3rd millennium. Architecture also flourished under Neo-Babylon, which saw the construction of the fabled Hanging Gardens, built by Nebuchadnezzar for his wife, who missed her home in modern-day Iran.

The Hanging Gardens were mentioned by writers of Greek and Roman origin; however, it is believed that the gardens were a legend.

An account by a Greek geographer named Estrabon described the Hanging Gardens in a 1st-century BCE text as vaulted terraces that were raised above one another and built on square pillars. Estrabon also provided details on the pillars, claiming that they were hollow and filled with sand to allow one to plant larger trees. Additionally, he claimed that the vaults, pillars, and terraces were created using asphalt and baked bricks. Other research also indicated that the Hanging Gardens site was also most likely not in Babylon, leaving many questions on the mystery of the site and its existence.

The Neo Babylonian era was also a period of great significance in art history since it saw the advancement of architectural structures such as the vault and the arch, which were refined under the new Babylonian empire. During this time, huge and complex palaces were built for King Nabucodonosor, who was among the most famous kings of Babylonia. Testimonials from clay cuneiform tablets also credit King Nabucodonosor for being a great leader in architectural development.

Two centuries later, after the fall of the empire, Alexander the Great sought to reinstate Babylon as his new Asian capital. Seleucus I Nicator was the victor after Alexander’s death and established a new city called Seleucia, on the Tigris. During this time, Greek influence infiltrated Babylonian-driven regions and saw the introduction of Greek theater and Hellenistic cultural influences. By the 2nd BCE, Babylon was already a diminished city that was conquered by the Parthians, leaving a few temples as the surviving aspects of the old city. The 1st century CE saw the production of the last surviving cuneiform texts, and as such, the last Babylon artifacts.

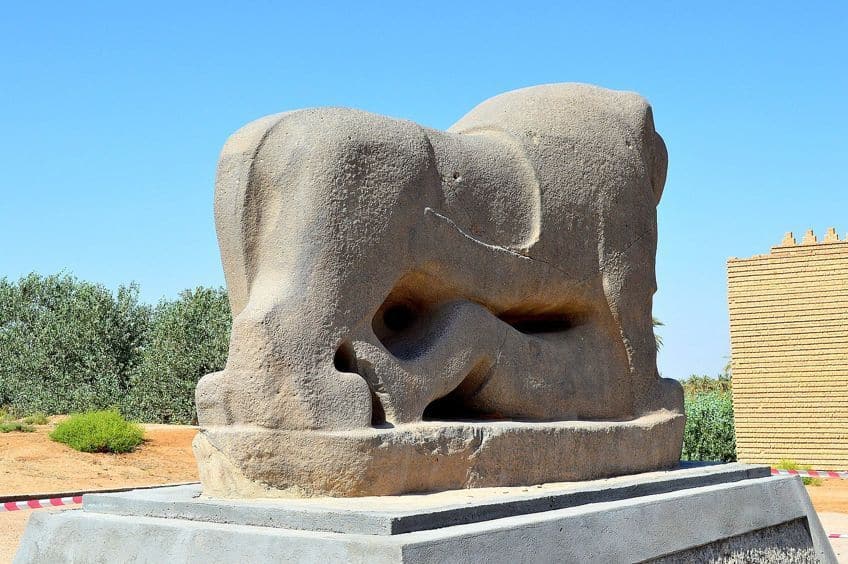

Composite Beings

In Neo-Babylonian ideology, there existed the notion of composite beings, which were Mesopotamian hybrid creatures that were often featured in ancient Babylonian art. These supernatural beings took many forms and are understood in German as mischwesen. It is believed that the idea of composite beings was adopted for multiple purposes, including rituals for the protection of individuals or households against diseases, perhaps represented by demonic entities. In a household, the corners of a house, its rooms, and the property’s gates would be occupied by wooden or clay Babylonian statues. Composite beings were also established on different cosmic levels, which are also mentioned in the Babylonian Map of the World text.

Composite creatures are also derived from two or more animals or species with each part of the animal embodying a natural behavior.

An example of this can be seen in a winged lion with the head of a human, which possesses the natural characteristic of human intelligence as well as ferocity and power from the lion and the swiftness of an eagle to access the sky. These models of divine symbols are complex and have also been used in relief sculptures as imperial propaganda or to mark the role of the king. Among the most common types of composite beings found in Mesopotamian art include the winged quadrupeds, a bull man called kusarikku, a dog-humanoid called ur(i)dimmu, wise sages called ūmu-apkallu, mermen called kulullû, and the snake-dragon being called mušḫuššu among many other unique variations.

Exploring the Art of Ancient Babylonian

The ancient world of Babylon offers much insight into the artistry of Babylonian sculptors and painters who leveraged their knowledge of Babylonian society and culture to create captivating works of art. Concepts such as perspective in Babylonian art may seem outdated by modern standards, however, the art of ancient Babylon possesses an allure like no other that transcends its technical limitations. One can get an idea of what Babylon paintings once looked like from the fragments of frescoes found at the Palace of Mari, of which only four exist with the most popular being the king’s audience chamber.

Below, we will dive into the best-surviving masterpieces of ancient Babylonia that will give us insight into the deliberate decisions, social beliefs, and structure of hierarchy that inspired many poets, writers, and artists.

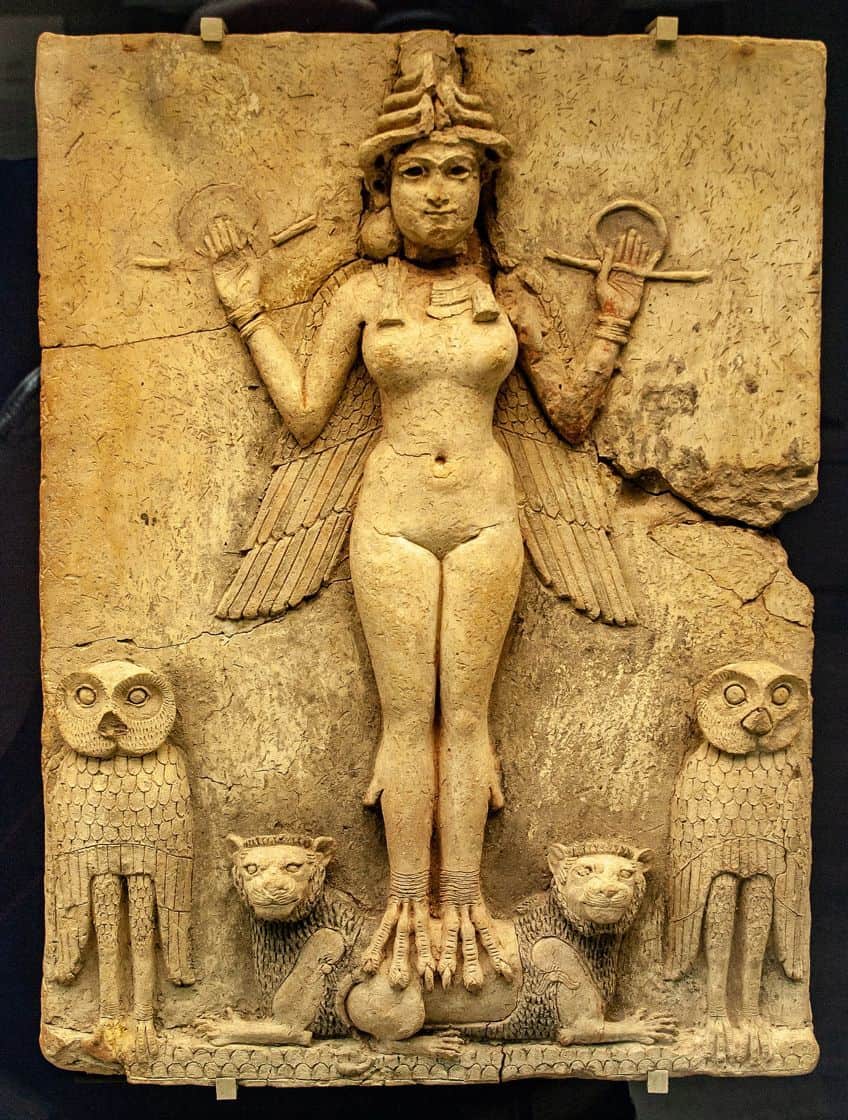

Queen of the Night (c. 1800 – 1750 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1800 – 1750 BCE |

| Medium | Hand-painted fired clay (Burney relief) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 37 x 4.8 x 49.5 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

This Queen of the Night plaque was created between 1800 and 1750 BCE and portrays a nude female figure with wings, talons, and a headdress with four pairs of horns and a disc. The elaborate detail paid to her jewelry as well as the lions and owls present on her sides also indicate that she was an icon of note.

This was further supported by similar motifs that appeared on molds and terracotta plaques found in Western Turkey. It is also believed that the figure was popular in ancient Girsu (Tello), where researchers discovered that the female figure was a mass-produced icon. Fired clay statues of guardians and deities were common in central and southern Mesopotamia with early evidence dating to the 2nds millennium BCE. The plaque was originally painted in red and black pigment, including white gypsum.

The image of the figure in the plaque is said to portray the deity rising from the underworld with her title, Queen of the Night, being the name of a species of night-blooming orchid cactus known as the Epiphyllum oxypetalum.

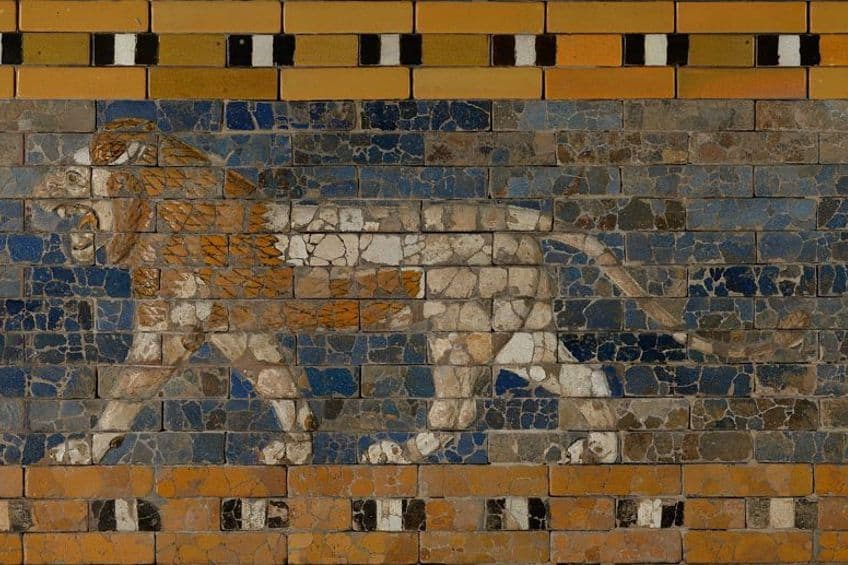

Panel with Striding Lion (c. 604 – 562 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 604 – 562 BCE |

| Medium | Ceramic and glaze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 99.7 x 230.5 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

This famous Panel with Striding Lion was a product of Neo Babylonia and represents a rare stone relief sculpture of a lion dating to between 604 and 562 BCE. The striding lion is a marker of a period in Babylon when the son of Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar II, established many unique embellishments in the city as part of its redevelopment. Nebuchadnezzar II was known to be a prolific statesman and war general who managed to keep the peace between the Medes and Egypt while controlling important trade relations on the eastern Mediterranean coast. One of his redevelopment plans included the striding lions, which were sculpted as reliefs on stone, which was rare in southern Mesopotamia. Babylon was an exception since Nebuchadnezzar II sought to create a city filled with color with relief figures of bulls, dragons, Gods, and lions in a brilliant array of yellow, blue, white, red, and black at the city entrance.

At the northern section of the Gate of Ishtar, striding lions were built alongside each other along the roadway. The symbol of the lion in Mesopotamian mythology was associated with the goddess of war and love with the relief of a lion acting as a symbol of protection for the road. The lion was also a feared animal that was equated with the character of the king and was thus a symbol of power over the natural world. The repeated design of the lion also served as a guide for the processional roadway, leading followers from the city to the temple. The remarkable size of the relief and the detailed body proportions of the lion is admirable for its time. Each brick was sculpted with its mold, while the artist behind the work emphasized the significant parts of the lion, such as its eyes and ears.

Through shaping, molding, and firing the glazed clay, the artists were able to preserve their artistic and deeply spiritual artwork.

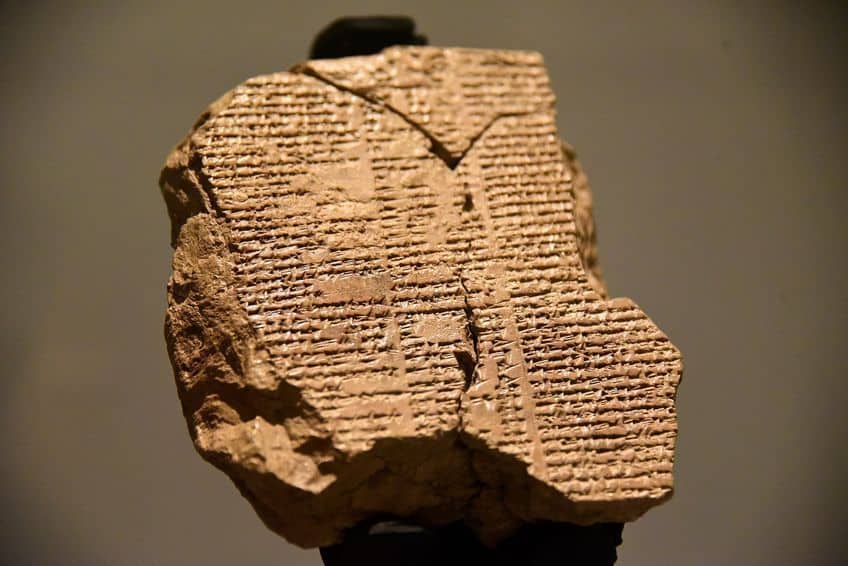

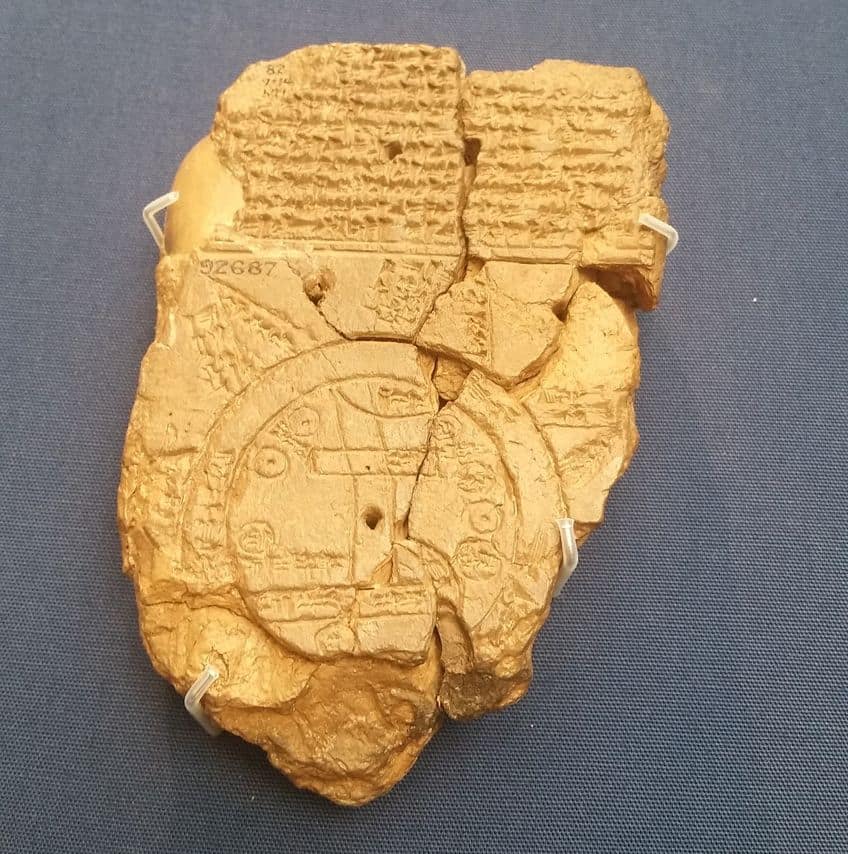

Map of the World (c. 6th Century BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 6th century BCE |

| Medium | Clay |

| Dimensions (cm) | 12.2 x 8 |

| Where It Is Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The Map of the World tablet is one of the most prized artifacts of ancient Babylon that also contains a cuneiform inscription on the reverse. The map portrays Babylon at the center of the map, visualized by a rectangle at the top of the circle. Other cities such as Elam and Assyria are also marked while the central arena is outlined by a circular-shaped waterway marked as the salt sea.

The rim of the salt sea is surrounded by eight other regions, each marked with a triangle and labeled as an “island” or “region”. The text on the back of the map describes the regions with stories of heroes and strange beasts that occupied these regions. The map is considered to be an important geographic artifact of the ancient world that shows accurate positions and was theorized to have been created to teach a Babylonian view of an alleged “mythological world”.

The clay tablet is no doubt a fascinating piece of Babylonian history that leaves one speculating about the possibilities for the existence of strange or mysterious creatures.

The Ishtar Gate (c. 575 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 575 BCE |

| Medium | Glazed bricks |

| Dimensions (cm) | 150 x 300 |

| Where It Is Housed | Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany |

The Ishtar Gate is perhaps the most iconic and significant piece from the Ziggurat that survives today at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. The gate was excavated by Robert Koldewey in 1904 and after the first world war, the gate was moved and reconstructed in the museum. The original foundation of the gate extended an extra 14 meters underground the excavation site while the visible parts of the gate are marked as 15 meters tall. The reconstruction at the Pergamon Museum is therefore not the complete version, however, it does give one rich insight into the artistic approaches of artisans and sculptures employed for such a refined development.

The gate was built to honor the goddess Ishtar and was built using glazed brick with a door made of cedar. The blue glaze on the bricks was also created to mimic lapis lazuli for an added regal effect and a jewel-like sheen. The gate portrayed three gods: Ishtar, Marduk, and Adad, who was accompanied by 120 lions, dragons, flowers, and bulls decorated in yellow and black to line the processional way. Marduk can also be seen at the front of the gate alongside his dragon Mušḫuššu. Marduk was worshiped for his ability to fight against evil.

Each brick in the gate was sculpted from fine-textured clay that was molded into wooden frames. The relief sculptures of the animals were also sculpted from bricks where clay would be pressed into the reusable molds. Bricks were then sun-dried and then fired before they were glazed. The colors used included blue, gold, white, and brown composed of a mixture of plant ash, pebbles, and sandstone conglomerates, which were melted, cooled, and powdered. Mineral pigments such as cobalt would be added to the final glaze for a vibrant color. After the glazes were applied, the bricks were then fired at a higher temperature. It is estimated that Babylon was decorated with around 15 million fired bricks, which reflects the importance of celebrations such as New Year and the Babylonians’ appreciation of gods and goddesses in the 6th century. The gate of Ishtar remains an example in the debate against the repatriation of artifacts to its original site, since the dangers of destruction during the Iraq War, provided critics with the argument that such artifacts may be safer in environments where they can be preserved.

Today, archaeologists continue to conserve the Babylonian site, which has also seen its fair share of destruction due to conservation interruptions, contentious reconstructions, military activity, and modern developments, which have hindered the preservation of the site. The art of Babylon was strongly intertwined with its religious and political belief system, which not only incorporated unique and complex symbols, but also demonstrated the culture’s dedication to sculpture and painting in making art a part of ceremonial practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Popular Art Forms of Ancient Babylon?

The ancient Babylonian society was best known for popular art forms such as relief sculpture, jewelry making, pottery, embossing, architecture, and painting as featured in vibrantly glazed and fired clay bricks.

What Were Common Themes in Babylon Paintings?

Popular themes featured in Babylon paintings include references to inaugurations, ceremonial offerings, mythological characters, composite beings, war, and sacrificial rituals.

How Did Babylonian Artists Portray Human Figures?

In ancient Babylonian art, artists portrayed human figures, most notably rulers, with styled beards, intricate patterns, headdresses, fringe details on garments, and long and curly hair.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Babylonian Art – Introducing the Art of Ancient Mesopotamia.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 10, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/babylonian-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 10 August). Babylonian Art – Introducing the Art of Ancient Mesopotamia. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/babylonian-art/

Davis, Liam. “Babylonian Art – Introducing the Art of Ancient Mesopotamia.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 10, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/babylonian-art/.