Brutalist Architecture – Designing Buildings With a Hard Edge

Brutalism was once an architectural style in vogue, but it has since fallen away. So, what is Brutalism? In this article, we will have a look at Brutalist design in general, including its history, and even some interior design. Keep reading to learn more about Brutalist architecture, its characteristics, and maybe even a Brutalist house or other structures. There are many to be seen.

A Look at Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture has a long history as a form of architecture that started in the 1950s, but only managed to truly last a few decades before its detractors gained more and more prominence. This form of architecture is often labeled as cold and totalitarian in design. Many pieces of Brutalist architecture have been vehemently attacked by a variety of forces, but many of these structures have continued to stand to this day. So, let’s have a look at what sets Brutalist architecture apart from other more ornate forms of architecture.

The IBM Building in Boca Raton, Florida (1970); Phillip Pessar, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The IBM Building in Boca Raton, Florida (1970); Phillip Pessar, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Characteristics of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture is a form of architecture that is characterized by its adherence to more of an ethic than a unified aesthetic. This was a concept described by the Smithsons, an architectural partnership that massively influenced the early development of Brutalist architecture in general. Brutalist architecture was meant to be utilitarian in design. It was meant to be minimalistic and to use bare materials that were also on display in the finished structure.

This meant that Brutalist buildings exposed their internal components so that unpainted concrete, steel frameworks, glass coverings, and monochromatic colorings would take center stage rather than any kind of decorative elements.

For this reason, Brutalist architecture was soon associated with many institutional buildings. Governmental structures, universities, and libraries were some of the most common structures that adopted a Brutalist style. It was a philosophical style more than it was a direct architectural style as it wanted something functional and would serve the purposes of the people for whom it was designed.

In addition, this form of architecture has its origins as a form of socialist architecture. It was made to serve the people and could be designed around low cost, pure functionality, and adherence to showing the inner workings of something made with the hands of working people. It was not illustrious or grandiose, and even the grandest structures that adopted this style were ultimately humble in their execution.

Some of the most common features of Brutalist architecture include exposed concrete, monochromatic palettes, the use of construction elements still present after construction, large forms, and unusual shapes. It was a form of architecture that highlighted itself and simultaneously wanted to be seen as humble regardless of where it was situated.

The Characteristics of Brutalist Interior Design

Brutalist interior design is a form of interior design that is effectively a reflection of Brutalist architecture. They cannot be seen as fundamentally distinct from one another as they are two sides of the same coin. Brutalist architecture, definitely, came first and is much more commonly regarded, but Brutalist interior design complements the more famous architectural design to produce a unified whole. Brutalist interior design makes use of the kind of bare concrete that is a notable aspect of Brutalist architecture, but there is also the use of heavy frames, geometric linework, and a monochromatic palette.

Buildings designed around a Brutalist aesthetic would generally shun decorative elements like paint and ornamentation.

The style, which was quite popular in the 1950s, is slowly making a comeback in the present day, especially in the form of Eco-Brutalism. This style originally developed during the post-World War 2 era, but it has become known as a more minimalist aesthetic in the present day that can be used to produce spaces that emphasize the depth of the location, the raw concrete form of it all, and an inherent neutrality that is especially in vogue at present.

A Few of the Architects of Brutalism

Alison Smithson (1928 – 1993) and Peter Smithson (1923 – 2003) were two English architects who served as some of the earliest proponents of Brutalist architecture. They designed structures such as the Hunstanton School, and they were also theorists in the urban theory of Brutalism. In addition, they were also married to one another. They were partners in architecture and matrimony.

Paul Marvin Rudolph (1918 – 1997) was an American architect. He would eventually go on to become the chair of the Department of Architecture at Yale University. He made use of reinforced concrete and complex floor plans throughout his architectural career. One of his most famous structures includes the Claire T. Carney Library in Dartmouth.

Ernő Goldfinger (1902 – 1987), despite having the same last name as a Bond villain, was a Hungarian architect who was also an influential designer of furniture. He became an important proponent of Modernism in general, and he is especially noted for his design of residential tower blocks. His Brutalist buildings include the Carradale House in Poplar.

The History of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture originates from a term that was coined by the Swedish architect Hans Asplund when he described Villa Göth (an early Brutalist house that will be explored below). He used the Swedish term “nybrutalism” to describe this structure, and this word literally translates to “New Brutalism.”

It was here that Brutalist architecture would start to develop into what it would eventually become.

The Development of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture is fundamentally a descendant of Modernist architecture in general, and it was developed as a reaction against the architecture of the 1940s and the nostalgia that people had for that form during the post-war period. The earliest architects who intentionally adopted this style, and used the English term, were the English architects Alison and Peter Smithson. They could go on to revolutionize what would become Brutalist architecture.

Brutalist architecture was more than just a style, it was also a socialist construction ethic that favored functionality over standard views of aesthetics. This form of architecture would only become more popular in 1955 after the release of an essay by Reyner Banham. He drew parallels between this form and béton brut, or “raw concrete.” This form would become even more popular as the decades ticked on. Brutalist architecture reached its height as it was used for low-cost social housing that was fundamentally functional and utilitarian in its design. It would soon spread around the world and influence the development of many institutional structures, which were particularly cognizant of the aims of Brutalism. However, this popularity was not meant to last.

The End and Criticism of Brutalist Architecture

During the late-70s architecture, Brutalist architecture started to see its decline. Brutalist architecture started to be associated with totalitarianism and urban decay. In all likelihood, this association was because of Brutalism’s adoption by some Soviet countries, such as Bulgaria, East Germany, and even the USSR. The style appealed to the socialist desires of these countries.

This then led to even more criticism of the style. There are some extremely big-name critics, such as King Charles III, who has repeatedly criticized Brutalist buildings as nothing but concrete behemoths.

In addition, Brutalist buildings appear to be the ones that are most likely to be the subject of demolition attempts and desires. Regular people often dislike and despise Brutalist architecture despite the common love for the form that is adopted by many professional architects. However, this can be seen as yet another instance of academic groups lacking an understanding of what the regular people want out of their structures. However, Brutalist architecture has refused to die.

The Resurgence of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture mostly died by the late-1970s/early-1980s, but the style has seen a resurgence. There has been a renewed interest in Brutalist architecture, especially since 2015, because of the publication of various books that glorify Brutalist buildings. In addition, Brutalist interior design and its minimalist aesthetic have become particularly in vogue among many people around the world.

Some of the more recent attempts at Brutalist architecture have made some changes, such as a general softening of the otherwise raw forms that this variety was originally known for, but it has still made something of a comeback. Other newer forms include Eco-Brutalism, in which the gray and concrete-oriented designs are accentuated with natural elements like plants and trees. Brutalist architecture may not be as big as it used to be, but there are still many examples of Brutalist buildings worth examining.

Examples of Brutalist Buildings

Let’s have a look at a few specific examples of Brutalist architecture. Below, we will consider a handful of Brutalist buildings, including Brutalist houses, government buildings, and libraries. Some of this architecture is from the earliest days of this form in the early 1950s, but one of them ushered in the beginning of 70s architecture using this style.

Keep reading to learn some more about five of the most famous Brutalist buildings.

Villa Göth (1949 – 1950) in Uppsala

| Architect | Bengt Edman (1921 – 2000) and Lennart Holm (1926 – 2009) |

| Date Constructed | 1949 – 1950 |

| Function | Residence |

| Location | Uppsala, Sweden |

Villa Göth is simply a house. It is not even necessarily a Brutalist house and was instead designed and constructed before there even was a Brutalism definition. Instead, this residence lies within the otherwise unassuming neighborhood of Kåbo in Uppsala. This structure has two floors and a basement, and it was built using dark bricks.

The house was designed with very plain windows, visible I-beams, and a flat and gabled roof, and it has a floor plan that allows the interior to be far more open than was standard at the time. There are other exposed construction elements throughout the structure and there are instances of dark brick being the same in the exterior and the interior.

This structure may not have been called a piece of Brutalist architecture as soon as it was built, but it was highlighted for its Béton brut style almost immediately. It was a stunning new example of a form of Modernist architecture the likes of which had never quite been seen before.

Brutalism as a distinct form would only really develop much later and became a popularized term with the release of the before-mentioned book by Reyner Banham. However, this particular structure somewhat originated the phrase when a Swedish architect remarked that this residence was a kind of nybrutalism, a term which literally means “new brutalism.” However, it took years before it would become a more commonly used term.

So, this residence may have been the originator of the concept. It may not have been developed with a Brutalist architectural style in mind, but that did not stop it from becoming one of the most influential buildings in the modern era. This is quite impressive for a fairly standard residence that was constructed for the head of the pharmaceutical company, Pharmacia, Elis Göth.

This residence would go on to become classified as a structure with special architectural interest to the country of Sweden. It achieved this special historical significance label in 1995, nearly half a decade after it was first built, but it does go to show that even structures that were not built to start any kind of an architectural revolution can become immensely structures in the history of world architecture.

Hunstanton School (1949 – 1954) in Hunstanton

| Architect | Alison Smithson (1928 – 1993) and Peter Smithson (1923 – 2003) |

| Date Constructed | 1949 – 1954 |

| Function | School |

| Location | Hunstanton, United Kingdom |

The Hunstanton School is not even called the Hunstanton School any longer. Instead, it has the name: Smithdon High School. The previous name had been based on the location, and it was very famous under the name, but decisions to change names get made all the time. The school itself is a rather small school that operates under the English comprehensive system. It has less than a thousand students and it only goes from the ages of 11 to 16. So, this is a relatively small school, but even a small school such as this can be an important piece of architectural history.

In this particular case, this comprehensive school in Norfolk was designed by Alison and Peter Smithson. This wife-and-husband partnership was a powerhouse during the height of Brutalist architecture, and they were some of the biggest proponents of it. In this particular case, the concept of Brutalist architecture did not quite exist yet. They designed this building and only afterwards did it become known as one of the earliest and most important pieces of the Brutalist tradition,

This school was designed to be modern in every way, and it became notable because of its extensive use of glass paneling around the structure, the steel frame, and that there is a free-standing water tower nearby that was particularly unusual for the time.

This building then became quite famous in the area and was known by the locals as “the glasshouse.” It was distinctive from everything around it. The partnered architects wanted to create a design that united modernist architecture with regular people and the community, and so the Hunstanton School used Mies van der Rohe’s work as an inspiration to create this structure with its exposed elements that would become known as New Brutalism. The term, used in that sense, was new. It later became the most commonly adopted label to describe this kind of architecture. A new genre had been born, and it would go on to influence the designs of many public structures.

The building itself is a two-story Brutalist building with a flat roof and a generally symmetrical design. There are two courtyards inside the building, and there is also a central hall that has a double-height design. Each of the classrooms is located on the first floor and they can be reached by individual staircases that were used to reduce the use of lengthy corridors, which were perceived to cause noise and disruption in a school setting.

Each of the classrooms is covered in glazed glass around a steel frame, and this extensively glazed paneling would turn out to be a bit of an issue for those inside the structure. While the kind of glazed exterior looks rather lovely, it also becomes incredibly hot in the summer and incredibly cold in the winter. So, they were ultimately replaced with clear glass panels to stop that from happening.

The Hunstanton School no longer has its immensely distinct blackened exterior, but it does still stand as an early example of the kind of Brutalist buildings that would go on to become so popular and influential for several decades. This was one of the first structures to use this form, and it is still standing.

Boston City Hall (1963 – 1968) in Boston

| Architect | Gerhard Kallmann (1915 – 2012) and Michael McKinnell (1935 – 2020) |

| Date Constructed | 1963 – 1968 |

| Function | Governmental offices |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

Boston City Hall is a government building named after the city in which it resides. It houses the office of the mayor of the city, and it also houses the Boston City Council. It was a structure that was built as a replacement for the original city hall building, and while it was designed using Brutalist architecture, it was immediately controversial for that decision.

The building is commonly voted to be one of the ugliest buildings in the United States and in the world. There have been numerous calls for the building to be torn down and replaced with something else. It has been repeatedly attacked ever since the construction was done in the first place. However, these attacks have generally come from those who are not members of the architectural profession.

Architects have had a much different response to the structure, and according to one particular poll, professional architects in the country voted it to be one of the top ten best architectural achievements in the United States. This is a clear example of the experts and the general public having vastly different responses to the same structure.

It is always interesting to see, especially because the calls to demolish this building persists to this day and are not a relic of some older hatred of Brutalist buildings that has since dissipated.

So, whether you like or dislike this building may be determined, even more so than usual, by the extremely polarizing viewpoints that this structure seems to pull out of people. Boston City Hall was predominantly designed by two architects, Gerhard Kallmann and Michael McKinnell, and they won a competition to design this structure. The idea that they had was to develop the kind of monumental designs that were seen as appropriate for government buildings at the time.

The pair of them designed a new and bold response to civic structures by incorporating elements from other sources. There were elements borrowed from the work of the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier and also from far older structures, such as Medieval and even Italian Renaissance town halls. They wanted to stay true to the kinds of granite structures that were prevalent throughout 19th century Boston, so they designed an exposed concrete piece of Brutalist architecture that could stand as a massive and imposing monument to the governmental forces within its walls.

This design made use of some more classical elements, like coffers and concrete columns as the structure itself was divided into three distinct sections. Each of these sections was differentiated from every other section through a functional and aesthetic perspective. The lowest portion of the city hall was designed with a brick-faced base that was partially constructed into a hillside. It had multiple levels that allowed easy access for some of the highest traffic portions of the government.

Then there was the intermediate section. This section was intended to house the offices of elected officials, like the mayor and city council. This entire section was designed to protrude from the structure and could be seen by passersby. It was made to appear important and have a symbolic value that the lowest section did not possess.

Lastly, the upper section contains office space that is hardly visited by the public. This is the location of the administrative and planning departments that are immensely important for city governance to proceed, but that doesn’t generally need to be visited by regular people all that often. This entire section was designed to utilize an open office plan that was later retracted (and has since led to ventilation problems as it was designed to be an open office rather than separated offices).

All of this contributed to an eclectic array of different architectural elements within one structure that allows for entirely different uses. The different general styles of different sections of the building also contribute to the Brutalist architectural dedication to a functionalist desire for structures. They should be tailored around what they need to be, not the other way around.

Norfolk Terrace and Suffolk Terrace (1964 – 1968) in Norwich

| Architect | Denys Lasdun and Partners |

| Date Constructed | 1964 – 1968 |

| Function | Student accommodation |

| Location | Norwich, United Kingdom |

The Norfolk Terrace and Suffolk Terrace is a very peculiar-looking series of structures. These Brutalist buildings are also known as “the Ziggurats” because of their particular aesthetic design. They were commissioned as some of the first buildings for this brand-new university that was going to be built beside the River Yare. The idea was that there would be a preservation of the surrounding landscape and that these new buildings would stand out within that new landscape.

The aim of the architects was for a “five-minute university,” which would allow the combination of departmental and residential structures together so that there would not need to be any lengthy commutes. It would be a highly concentrated style of building that would allow for a much more tight-knit community.

This ultimately led to the decision to create student accommodation that could be easily integrated into the university space.

This would result in one of the most interesting architectural sights in the modern world. This student accommodation was designed as a series of apartments in which 12 students could share a single kitchen and, in the meantime, create a good communal system for fraternal friendship to develop. So, each of these apartments is in the shape of a block that then led to each of them having a terrace that rested atop the apartment below them.

Thanks to this very specific design in which the apartments are stacked on top of each other in a stepped design, the structures became known as Ziggurats. For those unfamiliar, ziggurats are ancient structures predominantly found in Mesopotamia, and they are some of the precursors to many of the pyramids that would later be constructed in Egypt.

Sadly, the architects in charge of these structures never saw them completed, but they have since continued to be extended as the university itself continues to expand. Structures of this variety may not be for everyone, but they certainly are a sight to behold. Brutalist architecture allows for the development of structures like this that can appear both immensely unique and also distinctly industrial and modern.

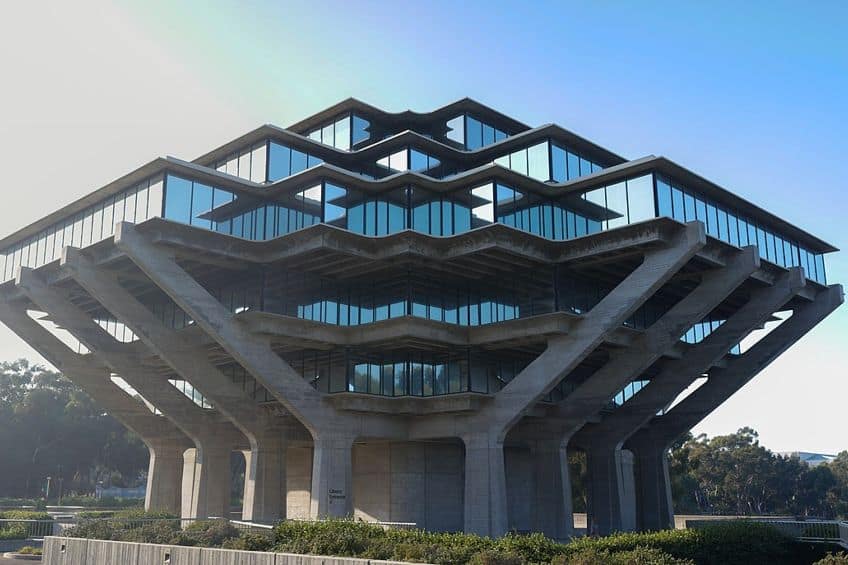

Geisel Library (1968 – 1970) in San Diego

| Architect | William Pereira (1909 – 1985) |

| Date Constructed | 1968 – 1970 |

| Function | University Library |

| Location | San Diego, California, United States |

Geisel Library is a large and uniquely structured library that serves as the primary library building for the University of California. This library has gone through several names, and it started its life as the Central Library but then became the University Library Building before finally resting on the current name. The name is actually in dedication to Audrey and Theodor Seuss Geisel (who is better known as Dr. Seuss). There is even a statue in dedication to him on the library grounds.

This building has become an immensely distinctive site on the campus grounds, and it is seen as a combination of Futurist and Brutalist architecture, but it does tend to be viewed as a central building within the annals of Brutalist design. In addition, it is one of the structures that would herald the Brutalist form during 70s architecture, especially in the United States.

The library itself is the home to a massive array of texts. There are over 7 million books within its walls for the purposes of research and educational needs of the students, lecturers, and researchers at the university.

There is also a Dr. Seuss collection that contains many of the original notebooks, drawings, and other pieces of Dr. Seuss memorabilia to peruse. So, this library is essentially the definitive location for all things Dr. Seuss if that’s what you’re looking for in this world. The idea for this library came from the design to develop a master plan for the university with the central library being a centerpiece in that overarching university design. The architect planned to develop this structure as a long-term project that would involve an extensive level of work as the center of the university itself needed to be moved. This would allow for a more clustered overall design, and it would match the design of the library itself.

The many levels of this library are intended to allow for the compartmentalization of the structure as a whole to suit different needs within the library, as was common in Brutalist design in general. Each of the floors of this structure, with its arched design, was intended to reflect the interior of the building onto the exterior. It is meant to look like hands holding up a stack of books, and while that interpretation may be somewhat abstract when you examine the building, it is easy enough to see that that was what they were going for after you know that intention. However, you may not immediately realize it upon seeing this Brutalist building.

Geisel Library (1968 – 1970) in San Diego; Westxtk, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Geisel Library (1968 – 1970) in San Diego; Westxtk, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There was also the idea that this structure could be built with the planning of later additions that would allow it to be altered when needed. As this is a library that is still in use, it has luckily served the purpose for which it was designed. It houses many stories of study and collection space. There are also two subterranean levels that allow for additional study space. This library is one of the most stunning examples of Brutalist architecture, but also a highly functional building that has been in use ever since its construction.

And with that, our discussion of Brutalist architecture has come to an end. We have provided a Brutalism definition alongside a discussion of the history, primary characteristics, architects, and a series of specific examples of Brutalist buildings. Hopefully, you learned a few things from this discussion and will now be able to speak about Brutalism with far more confidence than ever before. All that’s left to say is that we hope you have a great day/week/month ahead, and always keep learning!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is It Called Brutalism?

The name may confuse some English-speaking people as we do not generally view any form of architecture as something that could be described as brutal. That is simply not a word that is associated with buildings. The term actually comes from the French term Béton brut, which translates to raw concrete. It is a term that is used to describe the general concrete form of Brutalist architecture rather than meaning that buildings in this style are somehow brutal in their behavior.

What Is Brutalism?

Brutalism is an architectural style that is focused on a minimalist aesthetic. The form deliberately displays the base building materials and structural components of a structure rather than obscuring them behind decorative elements like paint and plaster. Brutalist architecture is also strongly associated with a socialist philosophy for the construction of functional buildings.

What Is Eco-Brutalism?

Eco-Brutalism is a more contemporary form of Brutalist architecture that takes nature into account. The natural world is incorporated into the general gray aesthetics of standard Brutalist architecture. This produces an interesting juxtaposition of heavy concrete aesthetics with natural greenery. An example of this would be the Tiing Hotel in Bali.

Justin van Huyssteen is a writer, academic, and educator from Cape Town, South Africa. He holds a master’s degree in Theory of Literature. His primary focus in this field is the analysis of artistic objects through a number of theoretical lenses. His predominant theoretical areas of interest include narratology and critical theory in general, with a particular focus on animal studies. Other than academia, he is a novelist, game reviewer, and freelance writer. Justin’s preferred architectural movements include the more modern and postmodern types of architecture, such as Bauhaus, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Brutalist, and Futurist varieties like sustainable architecture. Justin is working for artfilemagazine as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and about us.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Brutalist Architecture – Designing Buildings With a Hard Edge.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. August 18, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/brutalist-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 18 August). Brutalist Architecture – Designing Buildings With a Hard Edge. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/brutalist-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Brutalist Architecture – Designing Buildings With a Hard Edge.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, August 18, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/brutalist-architecture/.