Greek Art – A Deep Dive Into the World of Ancient Greek Art

The ancient Greek arts, otherwise known as the Athenian arts, are so ubiquitous in modern culture that we often forget how archaic it is. From the incredibly life-like and detailed Greek art and architecture, to the intricate ancient Greek artifacts that have been unearthed – Greek artwork has left a large legacy and had an unquantifiable impact on the Western world. The ancient Greek paintings, sculptures, and architecture that have been revered through the centuries demonstrate the high level of artistic competence that the ancient Greek artists possessed. This article will explore the history of these incredible ancient Greek artworks and the talented Greek artists who created them.

The History of Ancient Greek Artworks

This ancient civilization is imprinted in our cultural consciousness, owing partly to significant archaeological sites, renowned literary figures, and the influence of Hollywood, conjuring images of epic wars, brilliant philosophers, glistening temples, and life-like sculptures. The ancient Greeks spread throughout the Mediterranean and were subdivided into self-governing city-states, but they were unified by a common theology, language, and culture.

Although the prevalent contemporary perception of the ancient Greeks is centered on the classical Athenian arts from the 5th century, it is crucial to understand that Greek culture was widespread and did not arise instantaneously.

1600 – 1100 BCE: The Influence of the Mycenaeans

The Mycenaeans, regarded as the original Greeks, had an enduring impact on subsequent Greek art and architecture. Mycenae was a bronze-era culture that spanned southern Greece and the coastal areas of modern-day Italy, Turkey, and Syria. It was an elite military culture governed by royal states. Each royal state was controlled by a monarch with political, military, and religious power over three kinds of people: the king’s entourage, the regular citizens, and slaves. The civilization praised brave warriors and gave sacrifices to a pantheon of deities.

The achievements of these Trojan War heroes and deities became iconic in later Greek literature, notably Homer’s The Odyssey (c. 8th century BCE) and The Iliad (c. 8th century BCE), and were even used as origin myths by subsequent Greeks.

Trade and agriculture were the economic forces propelling Mycenaean growth, and both were aided by the Mycenaeans’ architectural expertise, as they built docks, reservoirs, aqueducts, bridges, drainage channels, and an extensive network of roadways that remained unequaled until the Roman period.

They were inventive architects, developing Cyclopean masonry, which used enormous rocks fitted together without mortar to construct massive fortresses. Later Greeks thought that only the Cyclops, terrible one-eyed titans of mythology, could have possibly raised the stones, thus the term Cyclopean stonework.

The Acropolis (c. 6th century BCE), a citadel erected on a hill that defined later Greek towns, was invented by the Mycenaeans.

The king’s palace was lavishly painted with murals depicting battles, marine life, parades, hunting, and supernatural beings. Scholars continue to argue how the Mycenaean civilization fell, with ideas ranging from invasions to internal warfare to natural catastrophes. The period was succeeded by the Greek Dark Ages, which are also referred to as the Geometric period.

776 – 480 BCE: The Greek Archaic Period

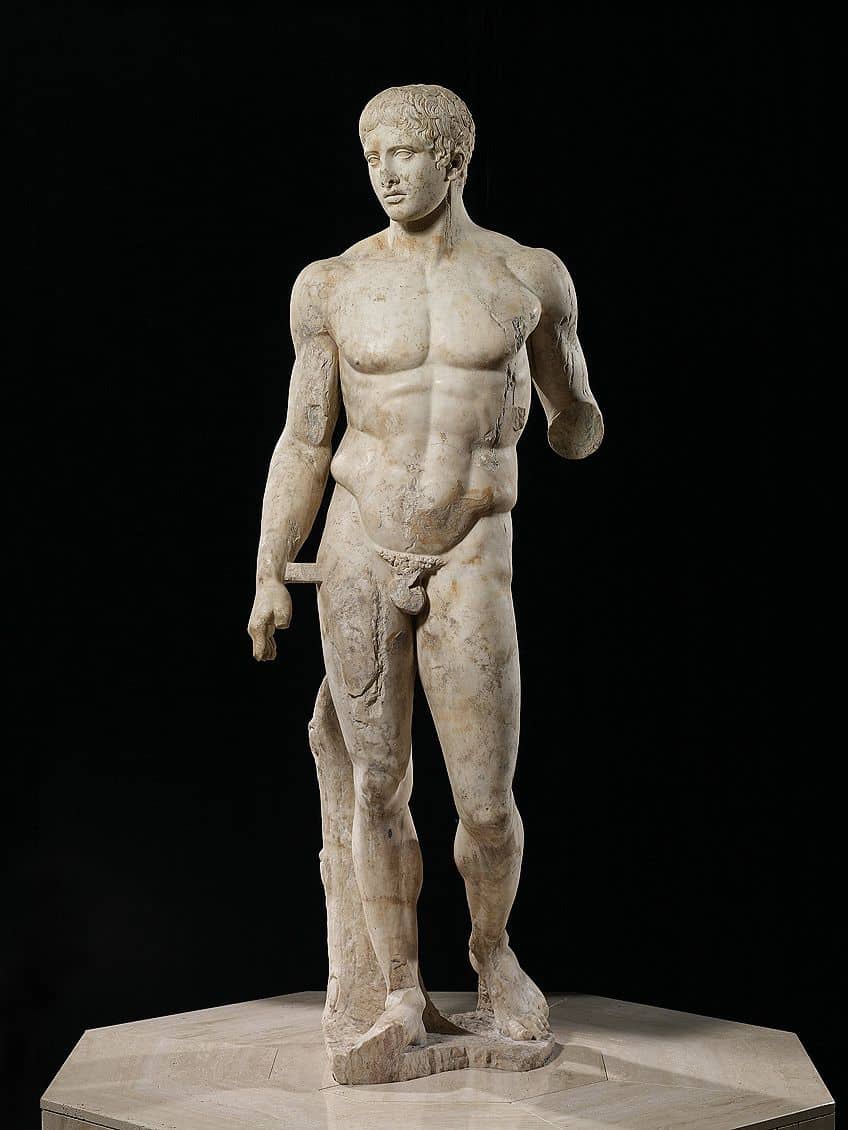

The Olympic Games were established in 776 BCE, ushering in the Archaic Period. Greeks felt that athletic competitions, which stressed human achievement, distinguished them from “barbarian”, non-Greek inhabitants. The Greeks idealized male athletes as a result of their veneration of the Mycenaean past as a heroic golden age, and the masculine figure became a dominating theme of Greek art. The Greeks believed that the naked male demonstrated not only the purity and elegance of the physique but also the noble character.

The city-states served as the foundation for the Greeks’ social and political framework. While Argus was a major commercial hub in the early days, Sparta, a city-state that valued military might, evolved to be the most powerful.

Athens became a forerunner in the arts, culture, sciences, and ideologies that would become the foundation of Western civilization. Even though the age was characterized by tyrant rule, Solon, a philosopher monarch, became ruler of Athens in 594 BCE and instituted major changes.

He formed a council to examine and confront the monarch, abolished the practice of enslaving individuals for debt, and formed a governing elite based on money rather than pedigree. The Greek economy was driven by extensive sea-faring trade, and Athens, along with other city-states, started building trading stations and towns around the Mediterranean. As a byproduct of these excursions, Greek cultural ideals influenced and co-mingled with other civilizations, especially the Etruscans of southern Italy.

The biggest aesthetic development of the Archaic era was figurative sculpture, which focused on idealized yet realistic figures.

The Greeks adapted the frontal stances of pharaohs and other important figures into pieces known as kore and kouros (young women and men) and, life-sized statues that were first created in the Cyclades islands in the 7th century BCE. The Greeks were inspired by Egyptian art. Individual sculptors, such as Kritios, Antenor, and Nesiotes, were honored and their names were kept for posterity throughout the late Archaic era.

The late Archaic period was distinguished by significant changes, as Athenian lawgiver Cleisthenes instituted new laws in 508 BCE, earning him the title “Father of Democracy”. To commemorate the end of tyrant rule, he ordered the sculptor Antenor to produce The Tyrannicides (510 BCE), a bronze sculpture representing Aristogeion and Harmonides, who killed Hipparchos, in 514 BCE.

Though the two were killed for the act, they became emblems of the democratic movement that culminated in Hippias’ banishment four years after, and they were regarded as the only Greeks deserving of immortality in art.

The commissioning of Antenor’s artwork was the first publicly financed art commission, and the theme was so significant that when Antenor’s piece was stolen during the Persian invasion in 483 BCE, Kritios was contracted to produce a replica. Kritios’ The Tyrannicides (c. 477 BCE) established the austere style, often known as the Early Classical style, by depicting realistic motion and individual personality, which had a significant impact on later sculpture.

480 – 323 BCE: Classical Greece

Classical Greece was an important era for the development of politics, philosophy, science, literature, art, and architecture. Thucydides, the famous Greek historian of the time, referred to the populist leader Pericles as “the first citizen of Athens”. Greek governance was characterized by equal rights for individuals (which only applied to adult Greek males), democratic processes, freedom of expression, and a society controlled by a citizen’s assembly. Pericles began the restoration of the Parthenon in Athens (447 – 432 BCE), which was directed by the artist Phidias, and positioned Athens as the most prominent city-state, extending its power throughout the Mediterranean area.

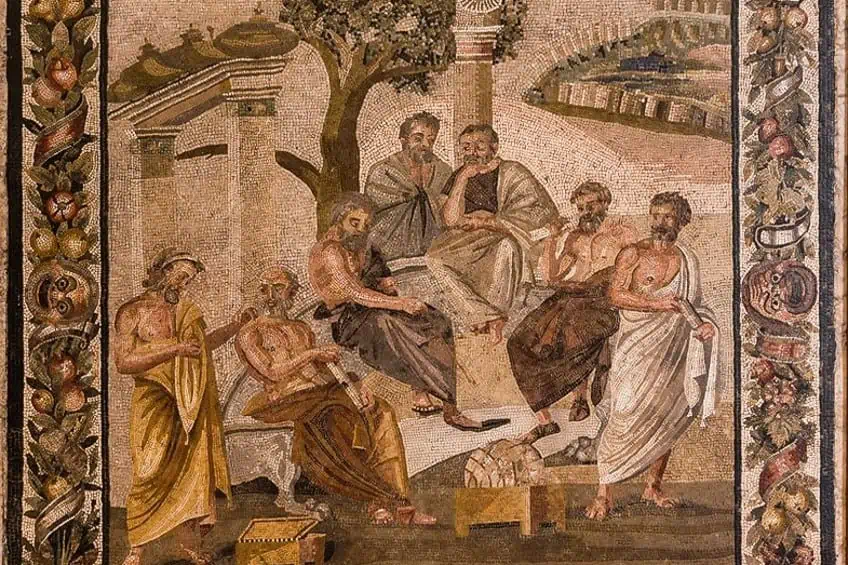

The theories and works of Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle established Western philosophy throughout the Classical period.

Plato’s written reports of his teacher’s dialogues preserved Socrates’ philosophy, and Plato proceeded to establish the Academy in Athens in 387 BCE, an early forerunner of all future universities and academic institutions. Many luminaries were educated at the Academy, most famously Aristotle, and it became a world-renowned force for the value of philosophical and scientific investigation founded on confidence in logic and knowledge. While their ideas differed in important ways, Aristotle and Plato both saw art as an emulation of nature, striving for the sublime.

Furthermore, the focus on personality resulted in more individualized art, and painters like Praxiteles, Phidias, and Myron rose to prominence.

The funerary sculpture started to depict actual individuals with emotional expression rather than idealized forms, whereas bronze works emphasized the human form, notably the male figure. Praxiteles, on the other hand, pioneered the female nude in his Aphrodite of Knidos (4th century BCE), a masterpiece that has been copied numerous times throughout the years.

323 – 31 BCE: The Hellenistic Greek Era

The Hellenistic period began with Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE. Alexander’s failure to select a successor after amassing a massive empire that spanned portions of North Africa, Asia, and Europe sparked a struggle between his commanders for control of his realm and local leaders jockeying for leadership of their territories. Finally, three generals decided to share authority and divided the Greek empire into three distinct territories.

While the influence of mainland Greece waned, Antioch in Syria and Alexandria in Egypt emerged as key Hellenistic cultural hubs. Many Greeks immigrated across the empire, “Hellenizing” the world.

Despite the empire’s fall, immense riches resulted in royal sponsorship of the arts, notably Ancient Greek paintings, and other types of Greek art and architecture. Lysippus, Alexander the Great’s royal artist, produced pieces in bronze after Alexander’s passing that signaled a shift from the Classical style to the Hellenistic style. The era produced some of the most important pieces of ancient Greek artwork, including the famous ancient Greek artifacts, the Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BCE), and Venus de Milo (100 BCE).

As towns built sophisticated theaters and parks for recreation, architecture shifted toward urban development. Temples grew to massive dimensions, and the Corinthian order, the most ornamental of Classical orders, was used in the architecture.

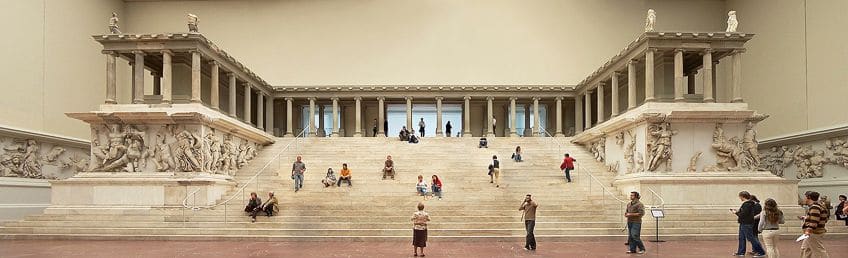

Pergamon became an important cultural center, famed for its massive constructions, such as the Pergamon Altar (c. 156 BCE) with its wide and dramatic friezes.

The Greeks progressively fell under the power of the Roman Republic throughout the Hellenistic era, beginning with Rome’s conquest of Macedonia at the Battle of Corinth in 146 BCE. King Attalus III died in 133 BCE, leaving the Kingdom of Pergamon to the Roman Empire. Despite Greek revolts, they were suppressed in the next century.

The Development of Greek Art and Architecture

The Greeks were renowned for their pottery, sculpture, architecture, and ancient Greek artifacts. As we have learned above, there were three distinct periods of ancient Greek art: the Archaic, the Classical, and the Hellenistic. We have covered the details of Archaic Greek artwork in another article, so we will go into more depth with the Classical and Hellenistic in this article.

Classical-Period Greek Art and Architecture

Victories against the Persians in 490 BCE established Athens as the most powerful of the Greek city-states. Notwithstanding external threats, it would continue to be the dominant cultural force for the following few centuries. Furthermore, during the 5th century BCE, Athens experienced an artistic renaissance that would not only influence future Roman artwork but would also serve as an ideal artistic benchmark for another 400 years when revived by the European Renaissance around 2,000 years later.

This is quite an achievement, considering that most ancient Greek paintings and sculptures have been destroyed.

Classical-Period Pottery

Ceramic art, and hence vase painting, declined gradually over this period. Researchers don’t know why, but based on the lack of creativity and the rising pathos of the designs, the genre seems to have peaked. The White Ground approach, introduced in about 500 BCE, was the ultimate creative advancement. Unlike the red-figure and black-figure styles, which used clay slips to form images, the White Ground method used paint and gilding on a white clay backdrop and is best exemplified by the late 5th-century funeral lekythos.

Apart from this one invention, the quality and creative worth of ancient Greek pottery dropped substantially, and it finally became reliant on the local Hellenistic schools.

Classical Greek Architecture

The two primary orders of Greek architecture, the Ionic and the Doric, came to establish a timeless, symmetrical, and universal ideal of architectural beauty throughout the Classical era, as did much ancient Greek artwork. The Ionic style was more casual and somewhat ornamental, and it gained popularity during the more laid-back Hellenistic age. The Doric style was more rigid and severe, and it predominated throughout the 4th and 5th centuries.

The Acropolis, a flat-topped holy hill outside of Athens, was probably the pinnacle of ancient Greek architecture.

The city-king state’s Pericles commissioned one of the most revered Greek artists, Phidias, to oversee the building of a new structure after the Persians demolished the original temples built here during the Archaic era in 480 BCE. At that time, the city-state was in the midst of its golden age. Although some of the new structures incorporated Ionic characteristics, the majority of them were created with Doric proportions. Several additions to the Acropolis were made during the following Hellenistic and Roman eras.

The most outstanding specimen of Greek Classical religious artwork is still the Parthenon (432 BCE). It would have had several statues and wall paintings when it was built, but even today, when it is comparatively bare, it is nevertheless a recognizable tribute to Greek culture. It was created by Callicrates and Ictinus and is the largest temple on the Acropolis hill. It is devoted to the goddess Athena. It once held a massive, multicolored figure of Athena the Virgin, whose body was carved from ivory by Phidias and whose attire was made of gold fabric.

Like other temples, the Parthenon was ornamented with free-standing sculptures made of bronze, marble, and chryselephantine.

Classical Greek Sculpture

Throughout the era, Greek artists’ technical ability to render the human body in lifelike positions instead of rigid stances improved dramatically. Anatomy got more realistic, and as a result, sculptures began to seem more lifelike. Bronze also became the primary material for free-standing sculptures due to its capacity to retain its shape, allowing for the carving of even more natural-looking positions.

Subjects were expanded to encompass the whole pantheon of Goddesses and Gods as well as lesser divinities, a wide range of mythical storylines, and a diversified array of heroes.

Other notable advancements were the adoption of a Platonic “Canon of Proportions” to construct an idealistic human figure, as well as the development of contrapposto. Classical Greek artists mostly worked in marble, bronze, bone, wood, and ivory. Using metal tools, stone sculptures were sculpted by hand from a slab of marble or high-quality limestone.

These artworks could be free-standing statues or friezes, which are only partly cut from a block of stone.

Bronze sculptures were seen to be better, owing to the higher expense of bronze, and were often produced using the lost wax process. Chryselephantine sculpture, which was reserved for important cult sculptures, was much more costly. Ivory carving, like wood carving, was a specialized art for small-scale, personal works.

Classical Greek Paintings

Classical Greek art demonstrates an unrivaled command of linear perspective and naturalist portrayal until the Italian High Renaissance. Aside from the painting of vases, all genres of painting thrived during the Classical period. The ultimate expressions, according to writers like Pausanias and Pliny, were panel paintings in tempera or encaustic. Subjects included realistic settings, portraits, and still-lifes, and exhibits were very popular, such as in Delphi and Athens.

Unfortunately, due to the delicate nature of these paintings, as well as centuries of theft or damage, not one of the Classical Greek panel paintings, nor any Roman replicas, have survived.

Fresco painting was a popular style of mural decoration on public buildings, temples, residences, and tombs, although these bigger works had a less prestigious status than panel works. The famed Tomb of the Diver (c. 480 BCE) at Paestum, one of several similar tomb embellishments in the Greek colonies in Italy, is the most recognized existing example of Greek wall painting. Another well-known piece was done for the Great Tomb at Vergina (c. 326 BCE), which had a massive wall painting of a royal lion chase. The backdrop was left white, with a lone tree and the ground line indicating the countryside.

Another specialized skill perfected by ancient Greek artists was the painting of terracotta, stone, and wood sculpture. Stone artworks were generally painted in bright colors; however, just the features of the statue depicting clothes or hair were frequently colored, leaving the skin in its original stone color, but on occasion, the whole sculpture was colored.

Sculpture painting was seen as a different art form – an early kind of mixed-media – instead of a sculptural improvement.

The statue could be embellished with valuable materials in addition to paint. Apollodorus, his student, the renowned Zeuxis of Heraclea, as well as Agatharchos, Parrhasius, and Timarete, were among the most prominent 5th-century Classical Greek artists.

Hellenistic-Period Greek Art and Architecture

The Hellenistic period begins with Alexander the Great’s demise and the integration of the Persian Empire into Greek culture. By this time, Hellenism had swept throughout the civilized world, with centers of Greek culture and arts including Antioch, Alexandria, Miletus, and Pergamum, in addition to villages and other settlements throughout Anatolia, Asia Minor, Italy, Egypt, Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes, and the other Aegean islands.

As a result, Greek culture was completely dominant. However, Alexander’s abrupt death precipitated a quick decrease in Greek imperial power.

Hellenistic-Period Architecture

The partitioning of the Greek Empire into different states, each with its own ruling family, opened up massive new potential for self-promotion. The Attalids established a new capital at Pergamon in Asia Minor; the Seleucids developed a sort of Baroque-style architecture design in Persia, and the Ptolemaic dynasty erected the library and lighthouse at Alexandria in Egypt.

To increase the power of local rulers, palatial architecture was rejuvenated and several municipal buildings were created. Temple architecture, on the other hand, has seen a significant decline.

The Greek peripheral temple lost much of its prominence after 300 BCE, except some development in the western part of Asia Minor, temple production came to a halt during the 3rd century, both in the Greek Mainland as well as in adjacent Greek colonies. Even gigantic constructions, like the Artemision in Sardis and the Apollo Temple in Didyma, made little headway.

All of this shifted in the 2nd century, when temple construction witnessed a revitalization, thanks in part to rising incomes, in part to changes implemented to the Ionic style by Hermogenes of Priene, and in part to the social propaganda war being waged between the multiple Hellenistic kingdoms, as well as between them and Rome.

Temple building was resurrected as a result, and a large number of Greek temples, in addition to small-scale constructions and shrines, were built in Egypt, southern Asia Minor, and North Africa.

In terms of styles, Hellenism desired the showier forms of the Corinthian and Ionic Orders, therefore the austere Doric style of temple building fell entirely out of favor. Notable examples of Hellenistic architecture include the clock house Tower of the Winds in Athens and the Stoa of Attalus, both of which were admired by the Roman architect Vitruvius.

Hellenistic-Period Sculpture

Hellenistic Greek sculpture carried on the Classical tendency of increasing realism. Animals, as well as regular people of all ages, were acceptable themes for Hellenistic era Greek sculpture, which was commonly commissioned to ornament the houses and gardens of affluent families or individuals. Greek artists were no longer obligated to depict women and men as standards of beauty.

In reality, the idealized classical tranquility of the 5th and 4th centuries began to give way to heightened expressionism, vivid realism, and an exaggeration of subject matter that was practically Baroque in nature.

As Greek culture spread, there was a considerably larger demand for sculptures and friezes of Greek deities and heroic figures for temples and public locations from newly developed foreign Greek cultural centers in Syria, Egypt, and Turkey.

As a result, a significant market formed for the manufacture and export of Greek sculptures, resulting in a decline in craftsmanship and innovation.

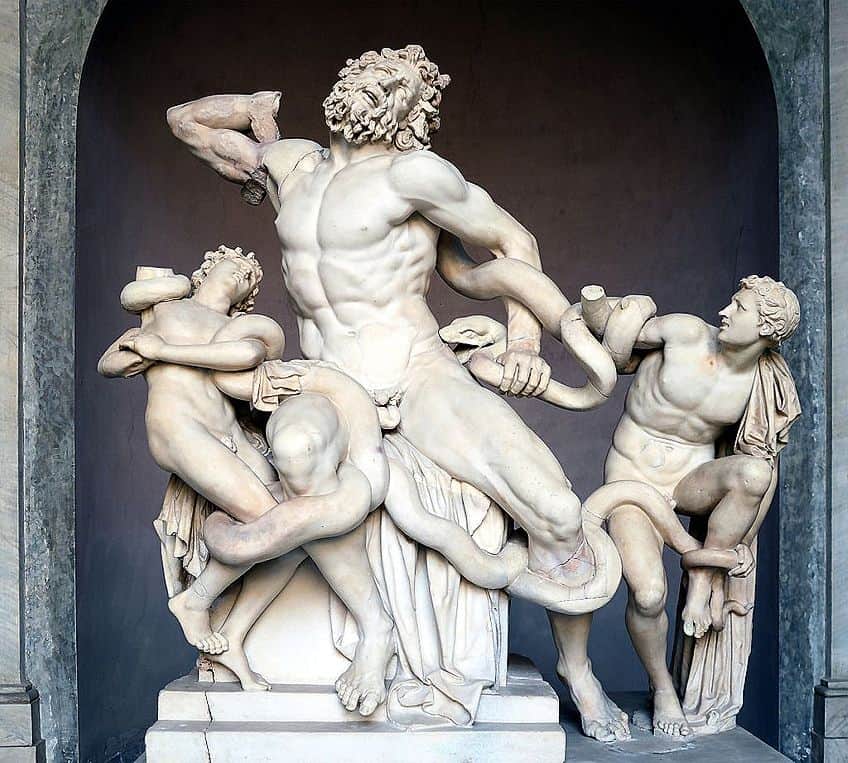

In their pursuit of greater expressionism, Greek sculptors turned to increasingly massive works, a tradition that culminated in the Colossus of Rhodes (c. 220 BCE). Notable Greek sculptures from the time include Epigonus’ Dying Gaul (232 BCE), Hagesander’s Laocoön and His Sons (c. 20 BCE), and the Winged Victory of Samothrace (c. 1st century BCE).

Hellenistic-Period Painting

The rising popularity of Hellenistic Greek art, which was instructed and promoted in several distinct schools both on mainland Greece and on the islands, paralleled the growing demands for Greek-style sculpture. In terms of subject matter, Classical favorites like mythology and current events gave way to animal studies, genre paintings, landscapes, still lifes, and other related subjects, which were principally inspired by the decorative styles discovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum, many of which are thought to be replicas of Greek originals.

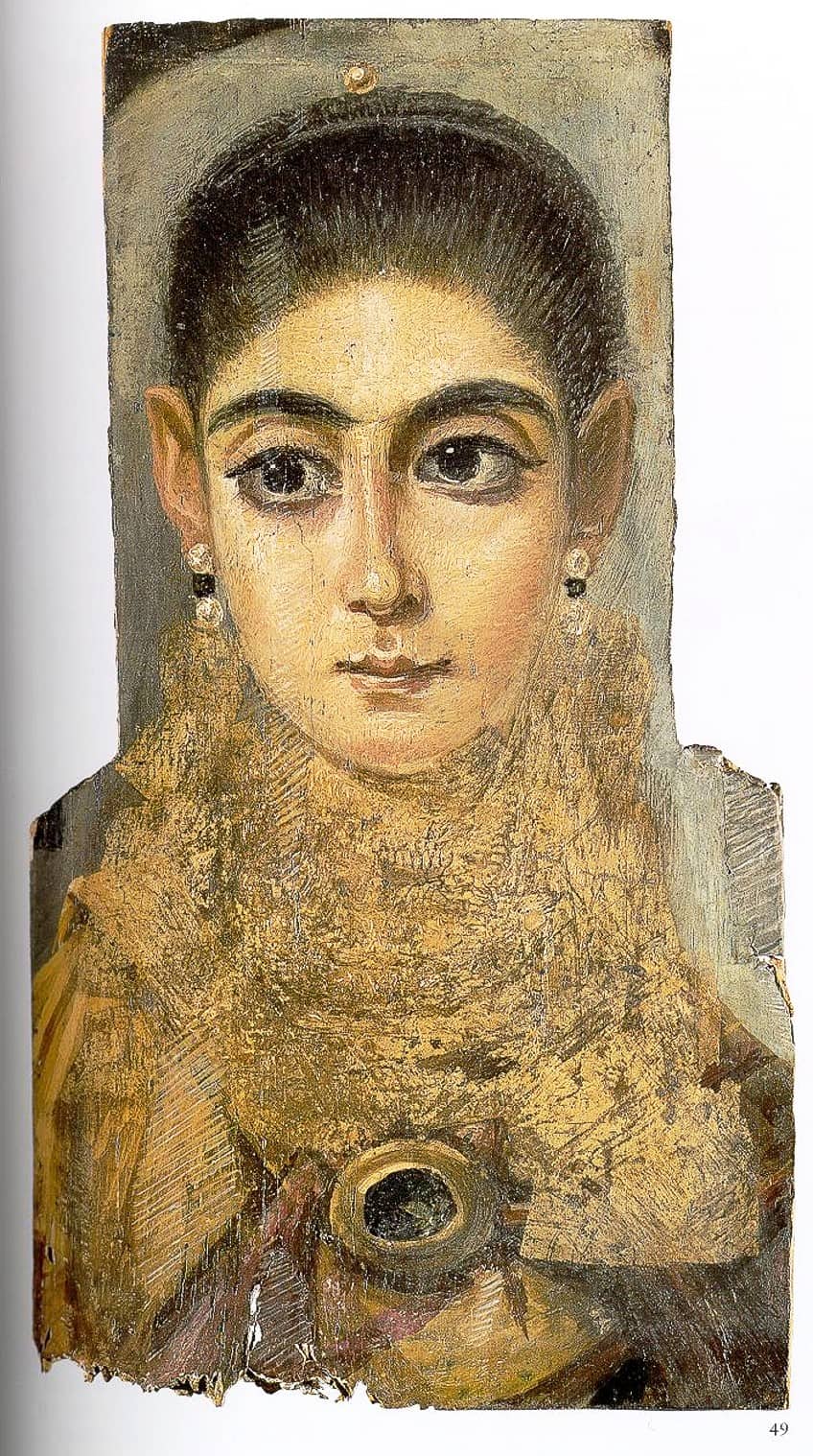

The Fayum mummy portraits, which date from the 1st century BCE, were arguably the best accomplishment of Hellenist Greek artists.

These superbly preserved Coptic era panel paintings – totaling over 900 pieces – are the only important body of art that has remained intact from Greek Antiquity. These lifelike facial images, largely found in Egypt’s Fayum Basin, were fastened to burial cloths to conceal the faces of mummified deceased.

Artistically, the pictures are more comparable to the Greek form of portraiture than any Egyptian tradition.

The Loss and Revival of Greek Art Traditions

The true tragedy of ancient Greek artwork is that so much of it has vanished. Only a few temples, such as the Temple of Hephaestus and the Parthenon, have survived. Only destroyed portions of Greece’s five World Wonders (the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, Zeus at Olympia, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria) have survived.

Likewise, the overwhelming bulk of sculpture has been lost.

Greek bronzes and other ancient Greek artifacts made from metal were generally melted down and used as weapons or tools, while stone sculptures were looted or broken up for building material. Approximately 99% of all ancient Greek paintings have likewise vanished.

Athenian Arts and Traditions Still Exist Due to Greek Artists

Even if this aspect of Greek heritage is no longer present, the traditions that gave rise to it are. By the time Greece was supplanted by Rome in the 1st century BCE, a large number of brilliant Greek artists had already moved to Italy, drawn by a large number of attractive commissions. These Greek artists and their creative successors prospered in Rome for around 500 years until escaping to Constantinople, the seat of Eastern Christianity, right before the barbarians stormed it in the 5th century CE, to produce new kinds of art.

They flourished here, at the center of Byzantine art, for nearly a thousand years before departing for Venice to help launch the Italian Renaissance.

Throughout the time, these migrant Greek artists preserved their traditions, which they passed on to the Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, and Modern eras. And during the 18th century, Greek architecture was a big attraction for adventurous Grand Tour travelers crossing the Ionian Sea from Naples. Although ancient Greek artworks may have vanished, Athenian art lives on in the principles of our institutions and the contributions of Greeks finest contemporary artists.

The Greek artists of this era changed the depiction of the human figure from the birth of ancient Greek artwork in about 800 BCE to its fall during the rule of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE. The fast development of figural portrayal and proportions became the defining feature of ancient Greek artwork over the ensuing centuries, and the feature most replicated by artists of both the succeeding Roman Empire as well as the Renaissance hundreds of years later. This ushered in the early Geometric Period, which proceeded past norms of idealized and abstracted forms.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Humanism Affect Ancient Greek Artworks?

The birth of humanism was a significant stimulus for the advancement of anatomical proportions in ancient Greek art. Humanism was an ideological or philosophical approach that emphasized the primacy of the human person over heavenly or celestial influences. Humanism stresses the human being’s capacity for success or excellence in all things by focusing on human experiences and naturalistic viewpoints.

What Were the Key Ideas of Ancient Greek Art?

The ideal human form quickly became the noblest topic of art in Greece, laying the groundwork for a beauty standard that was dominant for many generations of Western art. The Greek concept of beauty was founded on a standard of proportions, which regulated the portrayals of female and male forms and was founded on the golden ratio. While perfect proportions were important, ancient Greek Art aimed for increasing realism in anatomical images. This realism grew to include psychological and emotional realism, which produced dramatic tensions and pulled the audience in.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Greek Art – A Deep Dive Into the World of Ancient Greek Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 30, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/greek-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 30 November). Greek Art – A Deep Dive Into the World of Ancient Greek Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/greek-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Greek Art – A Deep Dive Into the World of Ancient Greek Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 30, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/greek-art/.