Mayan Art – The History of Important Mayan Artworks

The ancient Mayan arts are not as widely-publicized and considered particularly vital to education in the visual arts, which predominantly describes art history from a Western point of view. This article will introduce you to the classical artworks of the ancient Mayan visual arts and include all you need to know about the influence of Mayan culture in art and some of the most famous surviving art forms from the ancient world.

Introduction to the Mayan Civilization

The Mayans were a group of people under the Mesoamerican society characterized by their ancient architecture, complex writing systems, and contributions to astronomical systems, calendars, mathematics, and the visual arts. The Mayan civilization originated in present-day Southeast Mexico, including regions in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Belize among many other sites surrounding Mexico.

Some believe that this civilization died out a long time ago, but there remain more than six million descendants of the Mayan society to date with over 28 surviving languages. The Mayan civilization is not dead.

Crucial Developments in Mayan Society

Some important periods to consider when understanding the development of the Maya civilization include the Archaic period, occurring before 2000 BCE, which was characterized by the emergence of agriculture and villages. The period between 2000 BCE and 250 CE was known as the Preclassical period and was marked by the founding of the first complex Mayan societies and the cultivation of staple crops such as maize, beans, chili peppers, and squashes.

Crucial to the development of the ancient Mayans’ art was the development of monumental architecture, which occurred between 750 and 500 BCE.

This was defined by architectural elements such as detailed stucco facades and towering temples. The development of language and writing also saw the beginnings of hieroglyphic writing, which made its debut in the 3rd century.

By 250 CE, the Classic era saw the development of sculpture via monuments that featured Mesoamerican long count calendars.

These types of calendric systems were non-repetitive, base 20 (vigesimal) and base 18 (octodecimal) systems utilized by a few pre-Columbian cultures other than the Maya. This is what modern-day scholars recognize as the Mayan calendar. A day in the Mayan calendar is calculated using the number of days that passed since 11 August 3114 BCE, which is known as the date of mythical creation.

Mayan Politics

Mayan politics can be understood in tandem with the development of more organized communities within the society and across multiple regions. This also coincided with the development of trade networks and city-states, which indicated the growing need for leadership, organized connectivity, and protection. Two major rivals of the Maya society were the cities Tikal and Calakmul, which were two of the most powerful cities during the Classic era.

During this time, the leading city of Mesoamerican cultures, Teotihuacan, intervened in Mayan politics, and by the 9th century, Mayan society faced a political collapse.

The political instability incited an internecine war resulting in many people abandoning their cities and the migration of the population moving North. The Late Classic period was marked by the establishment of Chichen Itza, which was a massive Mayan-built society that lasted between 600 and 1200 CE. Chichen Itza can be located in Mexico in Tinúm Municipality in Yucatán State and showcases the diverse architectural style of the Northern Maya lowlands.

These central Mexican styles include the Chenes and the Puuc architectural style, often representing migration and cultural diffusion.

A Brief Overview of Maya Art

The 16th century marked a major turning point in Mesoamerican history, defined by the colonization of Mesoamerican regions by the Spanish Empire. The last Mayan city, Nojpetén, succumbed to the strategic campaigns of the Spanish and fell in 1697. Aside from the many important innovations of the Mayan society, the art featured in architecture and daily life formed a huge part of Mayan culture.

The ancient Mayans’ art forms are sophisticated and include a wide variety of visual art forms, including ceramics, sculpture, relief carvings, monuments, intricate murals, and the use of materials such as jade, obsidian, and wood.

For several hundred years, the Mayan Classic period birthed an influx of creative talent in the form of stone carvings across Mayan regions. Stone carvings were discovered on buildings, stairways, and pyramids, and often covered subject matter related to historical accounts, political leaders, and various pictorial symbols. Mayan art relied on stone stelae and limestone, which supported sculptural artists and engravers and resulted in some of the most beautiful images of noble society.

Art was both a form of expression and a record of cultural heritage, history, life, and religion.

Common Materials in Maya Art

The Mayans utilized a variety of materials and employed them in unique and creative ways to depict stories of valor, decorative artworks, commissioned art, and fashion accessories. The Mayan culture was famous for its broad use of materials such as shells, bone, stone, textiles, precious metals, clay, jade, wood, obsidian, gold, and silver. Precious metals like gold and silver were not often featured in art and were mostly transformed into jewelry for the elite.

The burial tombs of many kings and political leaders contained clay statues and Mayan temples often featured decorative murals.

Jade was also a rare commodity used in many precious ritual objects and originated from a single site near the Motagua River Valley in Guatemala. The amount of labor put into crafting and sculpting artworks was immense since the jade from this region ranked seven on the Mohs hardness scale, meaning that the stone was extremely hard. To process a raw boulder of jade into a polished object would involve both percussion and abrasion techniques, so one can only imagine the amount of effort it took to create such intricate and delicate works.

The use of jade in art was also a highly-specialized trade that not many would have been equipped to take on. This made the material incredibly valuable in ancient Maya and played a crucial role in displays of power, economic exchange, and cosmology. Jade was also seen as an incarnation of the element, water, in addition to breath and mist in its solid form.

Textiles were also separate art forms and have sadly not survived the test of time.

The main artists behind Mayan textile works were primarily women who were responsible for dyeing and weaving different textiles such as wool, cotton, and maguey cloth. These amazing works would then be embroidered with various designs and used as home décor as curtains, carpets, and drapery.

Art and Elitism

It is important to note that the majority of independent artists from Mayan society were commissioned primarily by members of society that were considered to be elite. Although artists came from varying levels of society, the works of the “talented” would go noticed by the elite who would commission artworks as a representation of their wealth and “maintenance” of social status.

The elite individuals were often related to high-ranking officials in government or rulers. This does not mean that there was a division in who would practice art in Mayan society.

On the contrary, a few artists were also considered members of the elite who specialized in different crafts. The arts and crafts were also commercialized and many families ran craft workshops where each family member played a role in the production process.

Featured Subject Matter and Color in Mayan Art

Some of the important subjects found in Maya art often contained imagery related to scenes from everyday Mayan life and murals that portray different Mayan Gods and high-ranking members of society. Almost every significant part of the culture was documented through art.

Other scenes included mythical figures, animals, humans, and influences of other Mesoamerican cultures on the Mayan civilization.

Another incredibly important deity in Mayan art was the Maize God, who was said to be the source from which humans were born and was also understood as the axis Mundi of the world (the center of the world represented by a tree), envisioned as a maize stalk. Many Mayan rulers would incorporate visual elements related to the Maize God, which conveyed the message that they were also the “centers of the world”, progenitors of mankind, and the source of all nourishment.

The most common colors found in Mayan art are red, black, yellow, and blue pigments. A special Maya blue color was invented by the Mayans and is a bright turquoise shade developed using a special technique. Mayan blue is referred to in Spanish as Azul Maya and consists of both organic and inorganic materials, including indigo dye sourced from the Indigofera suffruticosa plant mixed with a natural and rare clay called palygorskite.

According to recent research studies, it was found that Maya blue may have held a special meaning for the culture and was probably related to the ritualistic/ceremonial act of human sacrifice.

The pigment was most likely produced at sacrificial sites and applied to the victims’ bodies. The color is also representative of the blue haze seen in a flame, which is considered the hottest part of the flame and was therefore a “potent color”. The color originated around 800 CE and was applied in the paintings of the Nahua artist, Juan Gerson in Tecamachalco. Gerson’s paintings are significant since they demonstrate an amalgamation of European and Nahua techniques, also referred to as arte indocristiano.

Symbolism in Mayan Patterns

Maya art was heavily loaded with symbols as seen in the textile art of the surviving Mayan art in Guatemala. Some of the Mayan patterns include imagery of bats, which are regarded as creatures with a dual nature and are incredibly superstitious signs. The bat is also symbolic of the division between good and evil and the unity of both.

The cross is also one of the most famous Mayan patterns, which symbolizes the four cardinal directions and alludes to the connections between the Christian religion and Maya tradition.

The Mayan cross is crafted from four different types of corn (black, yellow, white, and red), which symbolize different body parts. The Mayan cross signifies air, darkness, water, and dawn. An inup refers to the tree of life, which is symbolic of the birth of humanity, reproduction, and death. The inup pattern also represents love and the union of two individuals that constitute two portions of the tree with the fruit representing children.

Among other important Mayan patterns on textile and sculpture works are the eagle, the owl, diamond shapes, corn, deer, jaguars, and flower motifs.

Mayan Artwork

Mayan art is incredibly rich and crammed with cultural and religious iconography from the ancient Mayan civilization. The most dominant art forms included sculpture, wall painting, and objects such as ornaments and jewelry items that demonstrate the potential and artistic vision of the time. We will now explore a few interesting examples of Mayan artwork across the fields of sculpture, painting, and pottery.

Mayan Sculpture

Mayan sculpture will have you in awe of the complexity and pride in the artistic execution of these once-pristine surviving works. From small Mayan statues to monumental Mayan carvings, the world of sculpture for the Maya was a playground. Below, you will find a few intriguing sculptures from ancient Maya that will enlighten and revitalize your interest in the medium.

Censer, Seated King (4th Century CE) From Guatemala

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date/Period | 4th Century CE |

| Location Found | Guatemala |

| Medium | Ceramic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 80 x 31.1 x 22.9 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

Around the first millennium BCE, artists from Mayan regions began to produce sculptures made from stone, wood, bone, stucco, fired clay, and shells. Powerful kings and queens from the Classic period commissioned many sculptures for their royal buildings and tombs. One of the most common mediums of ancient Mayan sculpture was wood but unfortunately, there are almost no surviving wooden sculptures that remain due to the tropical climate.

This sculpture by an unknown artist is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and once served a functional purpose as an incense holder.

This ornate object is sculpted in the form of a Maya ruler donning an intricate headdress and accessories. The subject is seated in the cross-legged position on top of a dome structure while holding ritual items. One of the items is a round plaque believed to represent a mirror. Beads made out of jade and once painted in a blue-green pigment are seen decorating the figure’s shoulders, biceps, ankles, and nostrils. The headdress on the figure illustrates wide eyes with a spiral pattern and beaded motifs on the forehead. The jaws of the deity are also highlighted by a strap that runs along the borders of the face and under the chin.

The ruler on the incense holder is said to have ruled the Mayans between 250 and 550 CE since four other similar sculptures have been discovered. The headband holds two feathers on either side of the head and complex ear accessories with cylinders through each ear. These large ear accessories allude to aspects of Maya culture that border between reality and the mythical beliefs of the culture.

The figure could be either a real person likened to a mythical figure or a mythical deity alone.

Incense was part of a ritualistic practice made by royal families and religious figures as a communication device between the deities, ancestors, and humans. The image of incense smoke can also be found in many monuments and murals portraying the ancestors of previous rulers who burned incense or used the sacred smoke to venerate a ruler after their death.

Costumed Figure (7th – 8th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date/Period | 7th – 8th Century CE |

| Location Found | Mexico |

| Medium | Ceramic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 29.3 x 9.7 x 9.5 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This colorful open-mouthed Mayan statue is one of the most famous Mayan statues from the ancient world. The Mayan statue was created between the 7th and 8th centuries in the Jaina style, which derived its name from an island on the coast of Campeche. Jaina was once a central hub from the late pre-classic era to the Terminal Classic era. Many statues recovered from the island depicted anthropomorphic figures and other Mayan statues made from a mold and detailed with paint as seen in the Costumed Figure.

Costumed Figure depicts a standing male figure dressed in a long bodysuit and adorned with a conical headdress.

He is sculpted with his mouth open as if caught speaking mid-conversation. The unknown artist included an ornament between his eyes and added finer details on his cheeks to show signs of aging. He is also wearing a ruffled collar and large ear flares. He holds a shield in his left hand that is carved with patterns in the shape of feathers. The statue is surprisingly also part of a whistle and was a mouthpiece.

The fact that the statue retained some color considering the climate of the time indicates that the original was probably a very striking and vivid sculpture. Traces of the artist’s fingerprints can be seen and indicate that the statue was hand-modeled on parts of the ear flare, face, and headdress. The figure’s face is painted blue, which is believed to be the trademark Maya blue. Most Jaina figurines represented idealized personalities as opposed to individual portraits.

It is believed that the Costumed Figure represents the “fat God’ who was portrayed across many Mesoamerican belief systems.

The hierarchical status of the deity is not clear and many scholars refer to the deity as the “fat man”, who may have been a ritualistic jester of sorts related to musical performance and humor during the Classic period. This Costumed Figure, on the other hand, is said to be a type of warrior featured in art found in the Northern lowland areas such as Dscelina and Oxkintok.

Deity Figure (3rd – 6th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date/Period | 3rd – 6th Century CE |

| Location Found | Copan, Honduras |

| Medium | Pyroxene jadeite (jade) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 10.8 x 6.4 x 2.3 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

Jade was a medium often used in the production of royal scepters, jewelry, and ritual objects. The color of jade ran across the blue-green spectrum and was known as yax in the ancient Mayan language. Jade was meant to symbolize water, primordial themes, and signal new growth, all of which were key themes seen in many Mayan statues, beads, and amulets in the lifestyles of the elites. Jade objects would also be included in burial tombs so that their owners would have wealth to carry into the afterlife.

This jade statue features a figure seated in the cross-legged position, which was a common position used by artists of the Early Classic period (250 – 500 CE).

The pose was called the crab-claw position seen in the statue as the figure’s hands curled up and bent toward the chest areas. The statue has the body of a human and the face of a supernatural deity known as the Principal Bird Deity and is a representation of the human version of the deity. The figure’s eyes contain square pupils, which are featured in other Mayan representations to indicate that the figure is a supernatural being. The figure is also decorated with jewelry seen in oversized ear flares, beaded bracelets, anklets, and a necklace with a beard below the chin.

A u-shaped design is seen between the deities’ eyebrows and is a feature often used in early Maya art to indicate precious materials. The artist behind this Mayan statue worked in great detail since the texture of the figure’s skin resembles that of jade beads and his calves contain beaded motifs. Mayan patterns such as the ones on the Deity Figure were painted onto the skin or carved on the stone to educate viewers on the physical appearance of important deities. Several other similar Mayan statues were discovered near Copan in Honduras and were once positioned in offertory caches as cosmic centers or rulers.

Other precious objects would then be scattered around the central jade figurine, including paint, and arranged to represent the four world directions and cosmic layers of the universe.

The avian deity was one of the most important Gods to the early Mayan population and served as the animate manifestation of jade itself. The Principal Bird Deity was also a personification of earthly wealth and in this statue, the deity is highlighted as a watery being since the artist chose to depict his forearms with a snakeskin quality. Art in the Mayan world was heavily connected to cosmology and physical embodiments of mythic/supernatural beings in the form of sculpture.

Pair of Carved Ornaments With the Maize God (5th – 7th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date/Period | 5th – 7th Century CE |

| Location Found | Southern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, or Belize |

| Medium | Shell |

| Dimensions (cm) | 5.7 x 4.8 x 0.3 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This decorative sculpture was created between the 5th and 7th centuries out of a shell and illustrates the severed head of the Maize God. The delicate ornaments once formed part of a set of ear spools (or ear flares) with a beaded assemblage and beaded counterweights. The use of shell as a medium was regarded as a precious material in ancient Maya and this makes these shell ornaments elite objects.

The frontal carvings of the shell ornaments were made by two separate artists with the left ornament exhibiting smoother and more refined line patterns while the artist of the ornament on the right seems to display a less confident touch.

The artist of the ornament sculpture on the right was probably a student or apprentice who assisted the artist on the left, who was more experienced with line carving and patterns. The ornaments display the defining contours of the Maize God’s face. This is not to say that the artist of the ornament on the right was less skilled, rather, the focus of each artist was different.

The artist of the right ornament focused more on the expression of depth than the artist on the left. Two different styles highlight the different styles that co-existed at the time and perhaps there were no preferred dominant styles among the elites. Another interesting fact about the depiction of the Maize God in ancient Maya was that it differed from time to time and was generally linked to the lifecycle of maize. Other artists sculpted and painted imagery of ripened ears, kernels, and dried cobs to serve as elements of the God’s body and appearance.

The Maize God was thus one with the maize itself and understood as a maize crop severed from its stalk when depicted as a decapitated head, as a harvest.

Depictions of the Maize God with a skeletal-like face represent dried corn and therefore the seeds that are sowed on the Earth to produce new green crops. This cycle is an ongoing series of birth, death, and rebirth through the lifecycle of crops and deities, who were understood as powerful figures that were born, sacrificed, and then resurrected.

Mayan Painting

Prominent painters from the Classic period in Mayan history produced numerous literature and illuminated manuscripts using hide or bark. In these books were many painted illustrations, drawings, and hieroglyphics that detailed the most important aspects of Maya culture, which relied heavily on celestial events, dates, and complex charts.

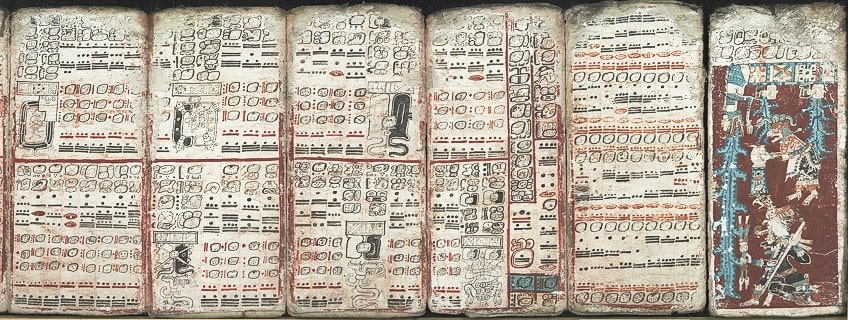

The Dresden Codex (11th – 12th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown; eight artists |

| Date/Period | 11th – 12th century CE |

| Medium | Amate |

| Dimensions (cm) | 20 x 370 |

| Where It Is Housed | Saxon State and University Library Dresden, Dresden, Germany |

One such surviving book is called the Dresden Codex, which was discovered in Dresden, Germany, and is currently housed at the Saxon State Library. The Dresden Codex is one of the most treasured books from the Mayan world with pages constructed out of amate, indigenous to Mexico.

The unfolded 78-page-long accordion-styled book is approximately 3.7 meters long and contains astronomical tables and references to religion, important moon and planet conjunctions, sickness, medicine, and seasons.

It is believed that the paintings and glyphs in the important Dresden Codex were created by talented craftsmen who used vegetable dyes and thin brushes for precision. The book was found to be written by eight scribes, each with its style.

Tripod Plate With Mythological Scene (7th – 8th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date/Period | 7th – 8th century CE |

| Location | Guatemala or Mexico |

| Medium | Ceramic; red, cream, and black slip |

| Dimensions (cm) | 41.9 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This bright polychrome feast plate showcases a mythological scene featuring Chahk, the Mayan God of rain depicted in an arrangement of hieroglyphics and designs alluding to the sea. One also sees three branches growing out of the Rain God, which transforms into deities.

The style of this Mayan painting is executed in a codex style, which was a common style associated with royal court paintings and local palaces within the city of Calakmul.

The imagery of the painting presents the Rain God as a key ingredient in a primordial process and deep time. Created by an unidentified artist, this Mayan painting also illustrates three Venus signs and body parts of the “starry Deer-Crocodile” on the upper half of the scene, which is representative of the sky. The month is documented as “4 Ceh” and is carried by a celestial flying creature that appears to survey the event.

So, what does the scene represent? It is believed that the scene represents sacred planted maize water or the sprouting of maize. Mythologically, the event occurs in a watery paradise in deep time with four Gods, including a jaguar that appears on the plate with its head thrust back.

The Rain God’s name is inscribed clearly as Chak-Xib-Chahk and is the main protagonist of the scene. His name, Chahk, translates to “red” and refers to either the color or Easterly direction, and perhaps a red sunrise.

Another important mythological figure is the Maize God who is seen emerging from the lower band of the plate. He is identified by an elongated cranium and is accompanied by another figure painted with tobacco leaves growing out of its head. The plate was most likely filled with maize tamales on special occasions and would have been a gesture of diplomacy between Mayan rulers.

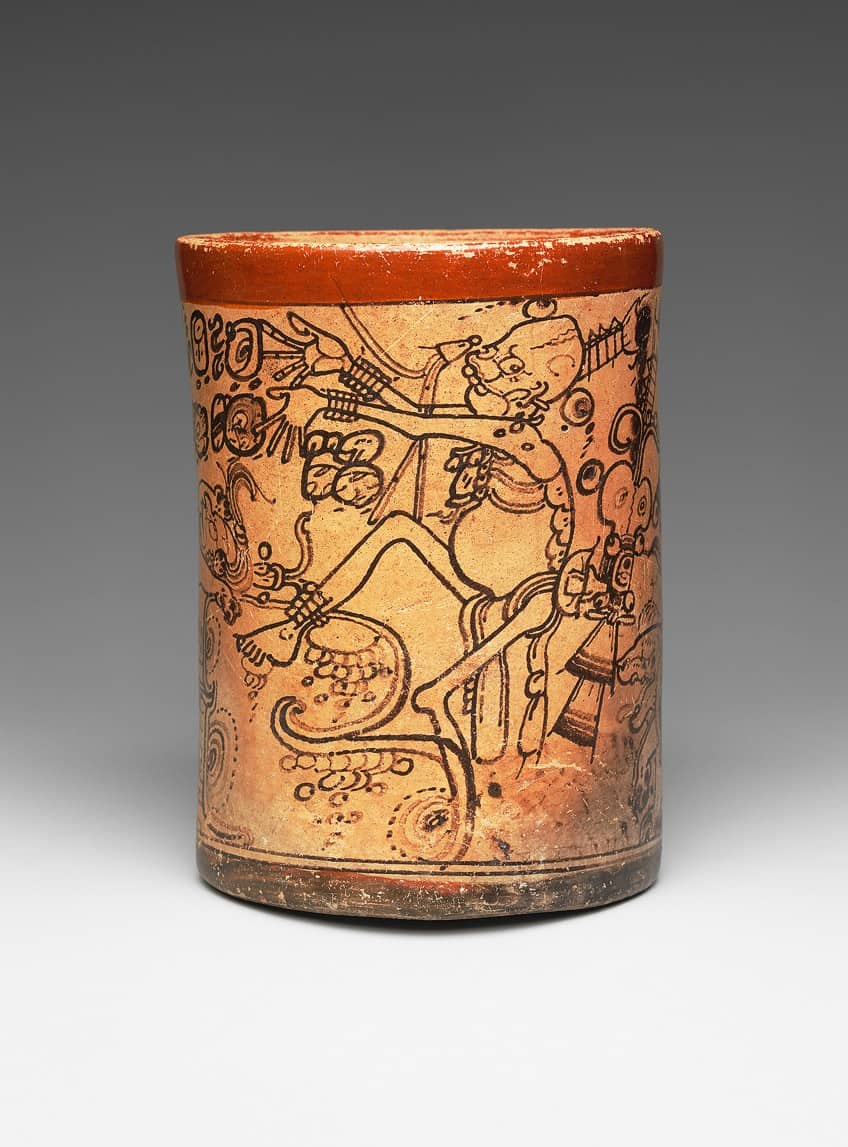

Vessel With Mythological Scene (7th – 8th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date/Period | 7th – 8th century CE |

| Location Found | Guatemala or Mexico |

| Medium | Ceramic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 19 x 11.1 x 10.8 x 11.2 x 34.2 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This Mayan drinking vessel was created similarly to that of the codex style and portrays a scene depicting the Rain God Chahk wielding an ax in his left hand with his right hand resting on a split stone temple. The motif of a grape bunch is seen on the right of the temple’s façade and alludes to a structure made from stone while the cross-hatch patterns indicate windows.

The Rain God is portrayed with a flowy vegetation headdress, fish-like barbels, and Spondylus ear spools.

Other depictions of the Rain God portray him with knotted and untamed hair. His body appears to be painted with as much Realism as possible, with saggy skin and a geriatric appearance. He is painted as the largest figure in the scene with two other figures placed in front of the temple. Chahk also appears to be vomiting smoke, which flows down to his legs and then up, such that he is engulfed in his own pool of vegetal smoke. The figure on the left is a young version of the Maize God, depicted with a cob-shaped head and tassel-styled hair in a mid-dance position.

The Maize God is accompanied by a captive figure with black face paint and his arms tied behind his back. The figure in captivity is said to be the nighttime version of the Maize God. Another mythological serpent enters through a quatrefoil void with an older God emerging from the serpent’s mouth. The artist painted the scene to be interpreted via the characters’ gazes as Chahk performs a ritual, believed to be the resurrection of the Maize God.

The fact that this scene was painted on a cup is also significant since the act of raising a cup was also an act of dedication as indicated by the text on the upper band of the vessel.

The owner of this stylish cup is marked as “striker” and was probably affiliated with the imagery of Chahk wielding an ax, thus indicating perhaps the profession of the cup’s owner. Thus, scholars believe that this alluded to the owner’s occupation in agriculture and farming. There are also interesting contrasts between the old Rain God and the youth of the Maize God.

The Mayan Murals of San Bartolo (100 BCE)

| Date | 100 BCE |

| Medium | Polychrome mineral pigments on wall |

| Dimensions (cm) | 200 x 150 (North wall) 945 x 220 (West wall) |

| Location | San Bartolo, Tikal, Guatemala |

This incredible site at San Bartolo is home to many stunning Mayan murals depicting narratives around the creation of the world and other popular Mayan belief systems. These wonderful polychrome Mayan murals are located in the Pyramid of the Paintings on the Western and Northern walls. These early artists created some of the most detailed portraits of Mayan mythology dating to around 100 BCE and covering a span of over 2 x 1 meters in the North and 9 x 2 meters in the West.

The Mayan murals on the North wall illustrate different mythical stories related to the birth of the first men on earth executed by the Maize God via a ritual.

The scene also contains images of infants, symbolic of the cardinal points and the center of the Earth. The mural on the west illustrates themes of creation and pre-Classic Maya kinship. Another excruciating practice represented on these murals includes the piercing of male reproductive organs, which was viewed as an act of self-sacrifice.

Toward the south section of the western mural are paintings showing the five trees of life set against the context of sacrificial offerings and the famous bloodletting ceremony where four individuals are seen offering themselves up.

There are numerous scenes on the San Bartolo murals that shed interesting insights into the ancient practices of the Maya and the mythological narratives that defined their way of life.

Another important aspect about the site and these murals are that they contain valuable hieroglyphics written in a pre-Classic Mayan system and are considered a unique discovery in the broader context of Mesoamerica. This proves that the Mayans developed their writing systems as early as 300 to 100 CE. The uniqueness of these murals goes undisputed and has served as a cornerstone of national identity for Guatemalan cultural heritage.

Interesting Mayan Art Facts

- The Mayans were among the first of the Mesoamerican societies to sign their work, which indicated artistic intention and recognition of an artist’s trade and style. Aside from the visual arts, the Mayans were also invested in performative arts and music and produced many complex instruments for the enjoyment of the elite.

- Another fact you may find interesting is that Mayan art also encompassed mask-making as portraits of the deities and kings. To do this, Mayan artists utilized stucco plaster and would carve ornate designs onto the masks. Kings would also commission their favorite artists for works that commemorate important life events, which reminds us of the documentative nature of Mayan art and the importance of preserving such heritage.

- The Mayan Classical era was the period that saw the tallest growth spurt in art production, especially Mayan carvings and stone stelae crafted from limestone. One of the hubs for art production was a city called Palenque, which was not considered powerful but was the production center of some of the best Mayan artworks.

The Mayans’ art is a rich source of ancient knowledge that informs us about the culture, mythological beliefs, and structured lifestyle that the Mayans followed. These spectacular Mayan artworks form part of a selection of many other amazing works of art that display complex thinking and systems around architecture, cosmology, and art. We hope that the art of this ancient civilization has inspired your interest in the multifaceted approach to thinking around art and its intersections with other aspects of human existence.

Take a look at our mayan artwork webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Most Common Art Forms in Mayan Art?

The most common art forms in Mayan art include ceramics, pottery, sculpture, murals, stone-carved objects, and ornaments, as well as stone relief carvings on architecture and temples.

What Are the Most Important Themes in Mayan Art?

The most important themes in Mayan art include mythic subjects and depictions of Gods such as the Maize God and the God of Rain. These figures would often feature themes of creation, fertility, and harvesting of the land, ritualistic processes, human sacrifice, celestial objects, cartography, and astronomy.

Does the Mayan Civilization Still Exist?

The Mayan civilization does still exist and is made up of a population of around six million people situated across Peru and parts of Mexico. The largest groups consist of the Yucatecs, the Tzotzil, and the Tzeltal cultures.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Mayan Art – The History of Important Mayan Artworks.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. December 12, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/mayan-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 12 December). Mayan Art – The History of Important Mayan Artworks. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/mayan-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Mayan Art – The History of Important Mayan Artworks.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, December 12, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/mayan-art/.