Minoan Art – Learn All About Important Minoan Art Pieces

The Aegean civilization from the Bronze Age was responsible for producing Minoan art. It is part of the larger categorization of Aegean art and, at a later stage had a dominant impact on Cycladic artwork. Because fabrics and wood have decayed, the best-preserved pieces of Minoan art include its palace architecture, Minoan frescoes, pottery, miniature Minoan sculptures, metal objects, jewelry, and Minoan artifacts such as finely carved seals. Let’s take a look at Minoan wall paintings, sculptures, and history, and answer any questions you might have, for instance, how do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?

Contents

An Exploration of Minoan Art

The neighboring cultures of the ancient Near East and Egypt had created complex urban art for far longer than the Minoans, but the style of the small but affluent trading Minoan towns was entirely different. We have little evidence of massive temple-based religion, rulers, or conflict in Minoan society, but plenty of creative energy and youthful vitality. All of these elements of Minoan civilization remain a mystery.

According to some historians, an essential element of the greatest Minoan art is the ability to convey a sense of movement and dynamism while adhering to a system of exceptionally formal standards.

The Style and Subjects of Minoan Art

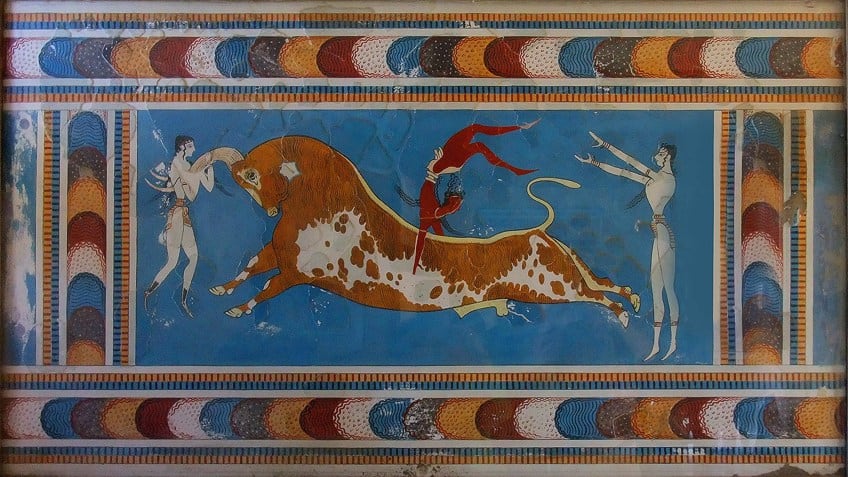

Minoan art encompasses a wide range of subject matter, with most of it represented in a multitude of mediums, however, only a few types of ceramics have realistic figures. Bull-leaping is a common topic in terracotta and other sculptural techniques and is regarded to have religious importance. Bulls’ heads are also a prominent subject in terracotta and other sculpting materials.

There are no images that seem to be portraits of people or that are unmistakably royal, and the designations of religious figures are frequently ambiguous, with researchers unsure whether they are priests, deities, or worshippers.

Similarly, it is unclear if the painted chambers were “temples” or secular; one room at Akrotiri has been proposed to be a bedroom, with remnants of a shrine or bed. Animals, which include a strange variety of ocean wildlife, are frequently illustrated; the “Marine Style” is a kind of colored palace ceramics that portray sea life, such as octopus, all over the container, and is thought to have arisen from related frescoed scenes; these pop up in other mediums. Hunting and battle scenes, as well as horses and hunters, are generally observed in later periods, either in works created by Cretans for a Mycenaean marketplace or the Mycenaean rulers of Crete.

While Minoan characters, whether animal or human, have a strong feeling of vitality and motion, they are sometimes inaccurate and difficult to recognize; when compared to Ancient Egyptian artwork, they are often more colorful but less lifelike. It has been suggested, however, that the representation of hybrid forms of blooming plants in Minoan frescos accentuates the ethereal, mystical character of the composition, as does the portrayal of flowers that blossom at different seasons.

When compared to other ancient cultures’ art, there is a large presence of female figures, although the concept that the Minoans had only goddesses and no male gods is now disproved.

The majority of human forms are in profile or follow an Egyptian tradition with the legs and head in profile and the torso displayed frontally; nonetheless, Minoan figures accentuate traits such as narrow male waists and big female breasts. Landscape painting can be seen in Minoan paintings and frescoes, painted pottery, and other mediums, although most of the time it comprises plants portrayed surrounding a landscape or scattered around inside it.

There is a visual tradition in which the surroundings of the principal subject matter are drawn out as though viewed from above, even though individuals are displayed in profile. This explains why rocks are displayed all around a picture, with flowers coming down from the top. The seascapes surrounding various images of boats and fish, as well as land with a village such as in the Ship Procession miniature fresco from Akrotiri, provide a larger environment and a more traditional arrangement of the vista.

Minoan Paintings

Several Minoan wall paintings have been discovered in Crete, usually in fragmented fragments that require extensive reconstruction; in some cases, barely 5% of a restored area is original. Surviving figurative specimens originate from the MM III period and beyond, with the same approach previously employed for basic colors and simple designs. They were most likely influenced by Egyptian or Syrian examples, with the former being more probable.

Santorini and Knossos are the most notable sites, and they were discovered in both big “palaces” of the towns (although not all of them) and in larger city residences.

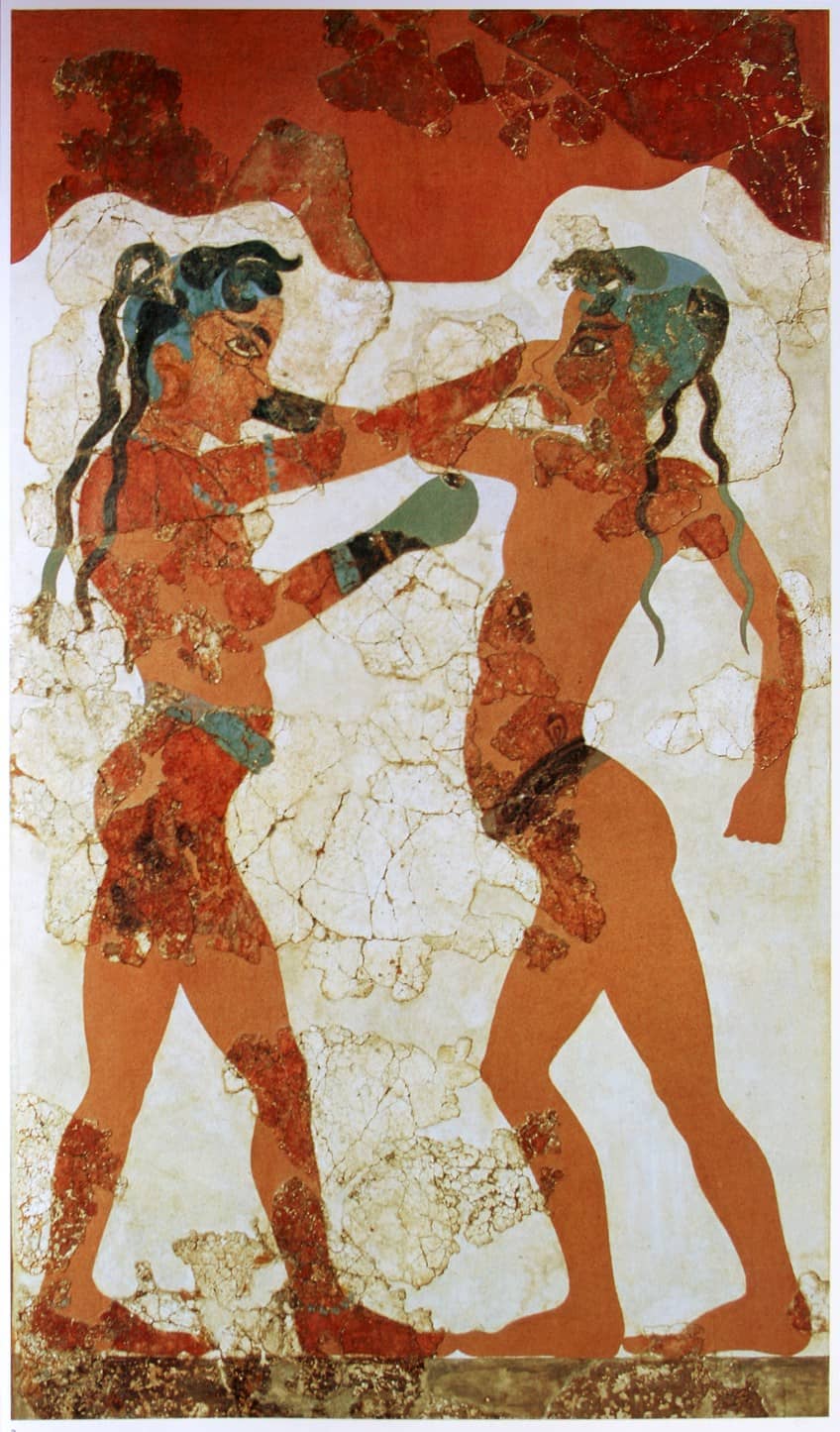

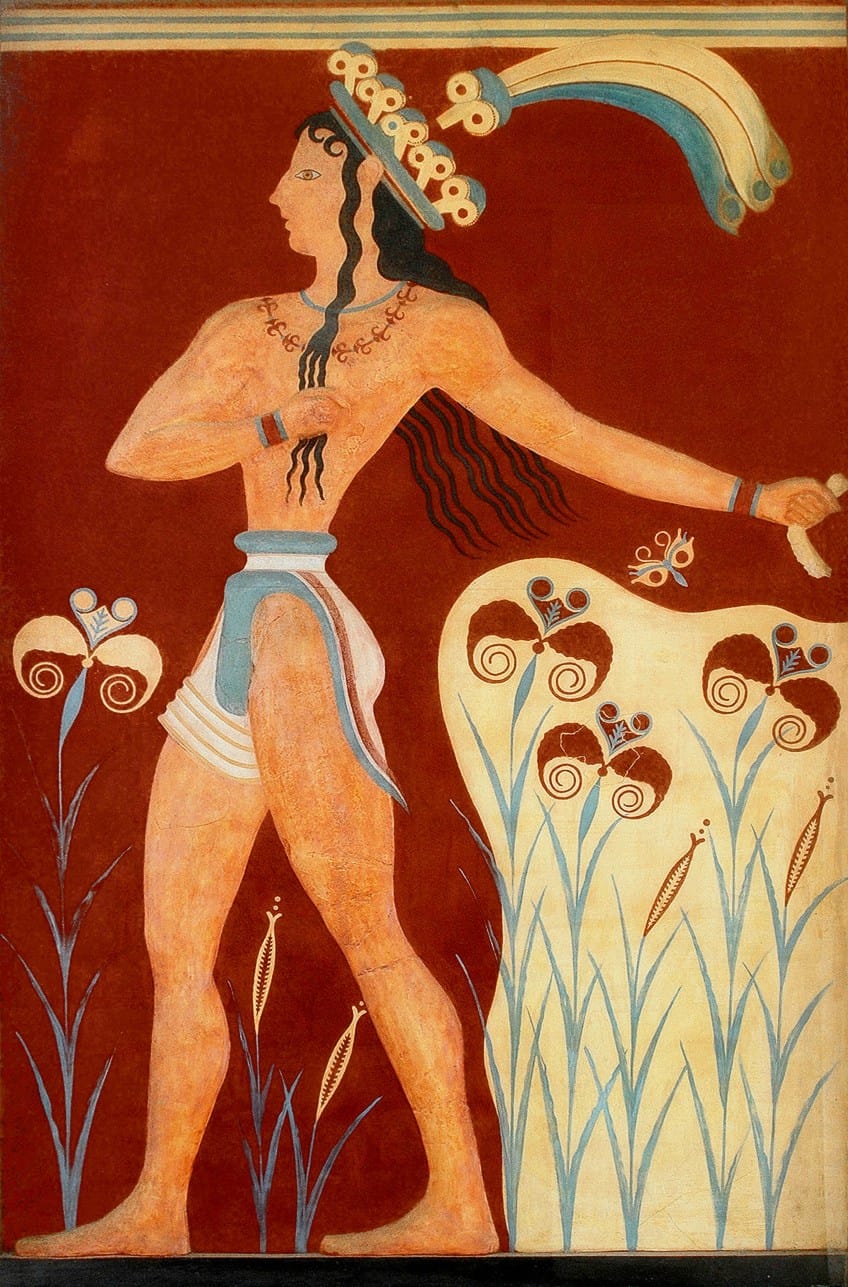

The Minoan frescoes represent many individuals, with the sexes differentiated by a more dramatic contrast of color than the equivalents in Egypt; the men’s complexion is a reddish-brown color, while the women’s appear white. The bull-leaping fresco is arguably the most well-known. Other well-known segments are the remnant known as La Parisienne as well as the Prince of the Lilies from Knossos, in addition to the Akrotiri Boxer Fresco, yet there are numerous others from Crete and other Aegean locations.

The painter Emile Gilliéron from Switzerland, and his son, Emile, were employed as the principal fresco restorers by Arthur Evans, the first archaeologist to explore Minoan Knossos. Subsequently, the restorations were heavily criticized, and professionals today regard them with healthy skepticism as “overly confident.” In one notable example, a monkey figurine was altered into a child; human beings do not typically feature in Minoan wall paintings of landscapes.

Spyridon Marinatos discovered the archaeological site of Akrotiri, then the city of Santorini, which includes the Wall Paintings of Thera, the second-most renowned Minoan landmark.

Although these Minoan paintings are less detailed, and their political link with Crete is unknown, the town was blanketed in volcanic ash during the Minoan eruption of approximately 1600 BC, and many of them have lasted significantly better than those from Crete. They contain life-size female figurines, one of whom appears to be a priestess. Early archaeologists saw the Minoan wall paintings as a natural method to adorn royal chambers, as they were during the Italian Renaissance, but more modern academics have linked them, or a number of them, to Minoan religion, which is still mostly unclear.

According to one commonly held belief, “the Aegean landscape continually exhibits a devotion for nature that suggests the pervasive influence of a Minoan goddess of nature.” The majority of the Minoan populace would have seen frescoes only in internal areas in structures held by the aristocracy. When they did get exposure, visual proof of the aristocratic class’s communion with divinity, even in landscape topics, may have had a strong psychological influence. Homer’s Odysseus refers to “Knossos, where Minos reigned, he who held discourse with almighty Zeus” many years later.

Frescoes first emerge in the Neopalatial Period, about the time when the summit sanctuaries seem to have become less utilized; the Knossos Saffron Gatherer fresco may be the oldest to leave substantial traces.

The Minoan frescoes often utilize “flat” colors – pure colors with little shading, mixing, or an attempt to convey shape within colored areas – with just a few indications of modeling. Many of the Minoan wall paintings were in the form of friezes, with many colored parallel stripes below and above the pictures to frame them. Dados were often painted plaster, sometimes simulating natural stone patterning, but in wealthier buildings, gypsum slabs or stone were used.

How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes? When they were found, it was stated that, unlike Egyptian frescoes, Crete possessed “genuine” frescoes that were put on wet plaster. This was later challenged and hotly debated, and it is possible that both wet and dry plaster were utilized at times in Italy. Wall painters appear to have been a unique category, and possibly the most regarded artists, generally, with some probable exceptions. However, they were most likely in contact with potters and gem carvers, and influence most likely flowed in both directions at times.

Ornamentation, which was also employed in ceramics, may occasionally aid in dating paintings, which is otherwise only attainable through style, which can be challenging.

Black, white, red, blue, yellow, and green are the primary colors utilized in Minoan frescos. Designs typically incorporate huge swaths of solid color as a backdrop. More complex sceneries frequently have the main individuals and some surroundings depicted near the edge of the painting, with plain sections in between. Early paintings utilized a red which was the standard color for simple painted walls, often with white, but later Egyptian blue became a prominent backdrop color, lasting until the late ages.

There are various Minoan or Minoan-inspired frescoes in the Aegean and on the Greek mainland, many of which were most likely painted by Minoan artists. Other locations include Alalakh and Tel Kabri. The excellent quality Minoan paintings uncovered at Tell el-Daba in Egypt may be the product of a political marriage with a Minoan princess during Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. They were unearthed between 1990 and 2007.

As with several Cretan palace frescoes, the painted plaster parts were eventually strewn outside the edifice. They contain bull-leaping scenes, hunting sequences, griffins, and Minoan-style female characters.

Miniature Minoan Frescoes and Reliefs

The first kind of fresco is a relief fresco, in which the plaster is shaped into a relief of the primary subject before it is colored, perhaps in emulation of stone reliefs in Egypt. Between the MM II and LM I eras, the method is largely, but not entirely, utilized at Knossos. The figures are enormous and feature people, griffins, bulls, and a lion capturing prey; these are the pieces that were part of the so-called Prince of the Lilies.

There might have also been ceiling reliefs of ornamental designs; the Minoans also painted certain floors with conventional frescoes, and the popular image of dolphins from Knossos could have been a floor painting.

There are also a few tiny frescoes featuring scenes with a high number of little characters rather than the customary few large ones. The small frescoes comprise some of the most intriguing subjects due to the big groups represented and, at times, the larger terrain. The late limestone Hagia Triada sarcophagus is exquisitely decorated and overall very well maintained.

It documents burial customs at a time when Crete was most likely governed by the Mycenaeans.

Minoan Sculpture

In stark contrast to other mainland civilizations and subsequent Ancient Greek art, huge Minoan sculptures are extremely rare. This might be partially explained by a shortage of appropriate stone, as there are smaller Minoan sculptures and indications for the existence of big wooden and perhaps metal figures in Crete, which could have been acrolithic and brightly colored. The Palaikastro Kouros is a unique artifact of a male figurine that might have been a cult icon. The body is fashioned of gold-foil-covered hippopotamus teeth, and the head is a sinuous stone with crystal eyes and ivory decorations.

It was purposely shattered when the city was plundered during the LM period and has been reassembled from numerous tiny fragments.

Small Minoan sculptures of various forms were typically exceptionally well crafted. Stone vases, often richly adorned in relief or by incisions, were manufactured in the Greek mainland and Egypt before the Bronze Age, and they occur in Crete, mainly in funerals or palace settings, from Early Minoan II onwards. Many were probably produced specifically for use as burial goods.

The most exquisite palace vases are rhyta, most likely for libations, and are molded into sculptural shapes like seashells or animal heads, with geometric designs or figurative images etched around the sides. They are usually too big and heavy to be used for dining, and many feature perforations at the bottom for pouring drinks. The majority of the time, soft or semi-precious stones like steatite are used.

A number of these are of particular concern to archaeologists because they depict comparatively elaborate scenes from Minoan life that are otherwise only found on tiny seals; for instance, the Chieftain Cup from Hagia Triada could be the most comprehensive portrayal of a Minoan ruler, the Harvester Vase taken from the same location possibly depicts a seasonal celebration, and a vase from Zagros depicts a peak retreat.

After pottery, Minoan seals are the most prevalent surviving piece of art, with many thousand known from EM II onwards, as well as over a thousand impressions, only a few of which match existing seals.

Cylinder seals were widespread in the early ages but were considerably less common afterward. Many early instances were most likely made of wood and have since rotten away. Soft stone and ivory were the most common surviving materials for early seals, the bodies of which were frequently shaped like birds or animals. Later, some are exceptionally well-etched gems, while others are gold seals. The topics displayed span, and even exceed, the whole range of Minoan artwork. The Theseus Ring was discovered in Athens; it is gold with a bull-leaping motif on the flat bezel.

The Pylos Combat Agate is a very exquisite engraved gem that was most likely created in the Late Minoan period but was discovered in a Mycenaean setting. Small ceramic Minoan sculptures were fairly prevalent, usually in the same terracotta as Minoan pottery, but also in Egyptian faience, a heated crushed quartz substance that was more costly. This was utilized for the one-of-a-kind snake goddess figurines discovered in the Temple Depositories of Knossos, which housed the biggest collection of Aegean faience artifacts.

Basic terracotta figures were frequently hand-formed and unadorned, while more elaborate ones were created on the wheel and ornamented. Vast numbers of animal and human figurines were produced as votive gifts across the Near East, and have been discovered in Crete’s hallowed caves and mountain sanctuaries. A late Minoan specimen of the poppy goddess form, with a circular vessel-like skirt, two uplifted hands, and characteristics sprouting from the diadem.

Some images are rather big, as are decorated clay animals that reach the size of a large dog, which were used as votive replacements for sacrificial animals; a set from Hagia Triada contains some human-headed forms.

The sarcophagus of Hagia Triada depicts two model animals being transported to an altar as part of burial ceremonies. The few bronze statues were most likely manufactured after MM III. They are considered votives since they usually depict worshipers, but also diverse animals and, at the Ashmolean Museum, a crawling infant. Despite the difficulty of making solid bronze figures with lost wax casting, the surfaces are not polished after having been cast., providing them with a Rodinesque appearance. Many contain casting flaws; for instance, the famed and spectacular bull-leaper set in the British Museum appears to be missing or missing portions of the thinner extremities.

Other smaller Minoan sculptures, many of which are in relief, are made of teeth from various animals, ivory, bone, and seashell. Wood has been extremely seldom preserved, although it was undoubtedly fairly common. Throughout the era, North Syria possessed elephants, and ivory imported from there or Africa appears to have been freely accessible for royal art.

Uncarved tusks were discovered in the ruined palace at Zagros.

A gold-plated ivory board game from Knossos elaborately decorated with motifs and decorative elements has lost the wood that likely formed the majority of the original, but it is the most fully preserved of the extravagant decorative objects of palace objects from later periods, comparable to instances from Egypt and the Near East.

Minoan Ceramics

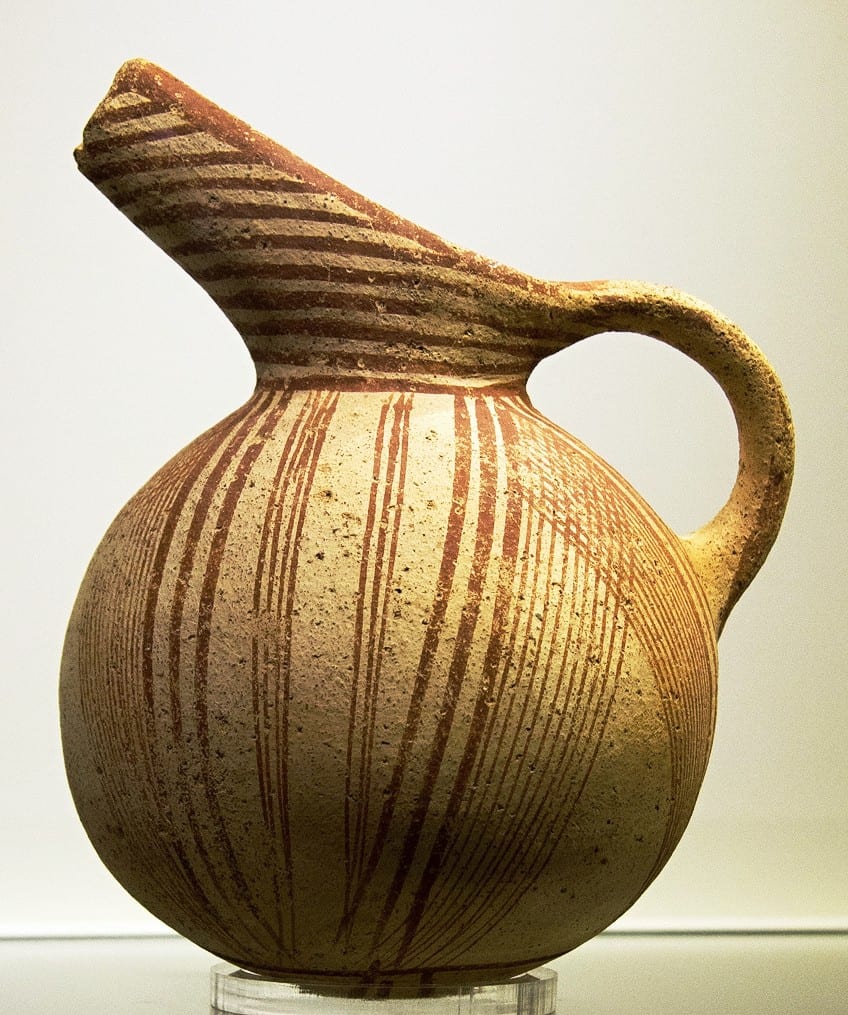

Throughout Crete’s history, several diverse forms of ceramics and production processes may be found. Early Minoan pottery included triangles, spirals, crosses, curved lines, fish bones, and beak spouts. While many of the artistic themes in the Early Minoan era are identical, there are significant differences in the replication of these methods across the island that show a range of shifts in style as well as power systems.

Naturalistic patterns (such as squid, fish, birds, and flowers) were popular throughout the Middle Minoan era.

Animals and flowers were still common in the Late Minoan period, but there was more diversity. Paintings depicting human figures, in comparison to later Ancient Greek vase art, are exceedingly rare, and those of land animals are not prevalent until the late eras. Shapes and decorations were frequently adopted from metal dinnerware, which has mostly disappeared, while painted artwork is most likely derived from frescoes.

EM I Era Ceramics

The Coarse Dark Burnished type was one of the first in EM I. This type most closely resembles Neolithic methods. Following the advancement of new methods that enabled the emergence of new modes of pottery in the early Bronze Age, the Dark Burnished type remained in production, and while most products from the Coarse Dark Burnished type are typically less lavish than other types that incorporate the new technologies that arose during EM I, some elaborate pieces exist.

This might imply that there was a desire among the groups that made Coarse Dark Burnished pottery to distinguish themselves from the groups that manufactured goods using new methods.

The Lebena and Aghios Onouphrios kinds were two of the most common forms of pottery that employed methods that had no precedent. Both styles used a range of novel techniques, including material selection and manipulation, the firing process, sapping, and decoration. Both styles employed tiny line designs to decorate the jars. In the instance of Aghios Onouphrios, the vessels had a white backing and crimson lining. In the Lebena style, however, white lines were painted on a red backdrop. Pyrgos ware was another EM I type of pottery. The style may have been imported and it may resemble wood. Pyrgos products employ both ancient and innovative processes.

Pyrgos ceramics are a subset of the Fine Dark Burnished class with distinctive burnished designs. The patterning is most likely caused by a failure to correctly paint the dark backdrop of the style.

These three EM I pottery types effectively demonstrate the variety of methods that arose over time. The Coarse Dark Burnished class employed existing techniques, the Lebana and Aghios Onouphrios type used entirely new techniques, and the Fine Dark Burnished type used a blend of ancient and new techniques. Other EM I goods, such as the Red to Brown Monochrome, the scored, and Cycladic types, have been unearthed. Furthermore, various forms of pottery were used in each style.

EM II & III Era Ceramics

The Aghios Onouphrios pottery is particularly widespread in the early Minoan period. Vasiliki pottery is present in East Crete during the EM IIA era, but it is not until the next period, EM IIB, that it emerges as the dominating form among fine goods in southern and eastern Crete. A reddish wash is present in both types. Vasiliki clay, on the other hand, has a distinct mottled finish that differentiates it from EM I ceramics. This irregular finish appears planned and organized at times, and uncontrollable at others.

During this time, a number of pottery classifications evolved, similar to EM I. Koumasa wares were a ceramic development of the Lebana and Aghios styles that were prevalent in EM IIA before the emergence of Vasiliki wares.

Gray goods were also produced throughout EM II, and a Fine Gray type of craft emerged. The Fine Gray type follows a significant amount of EM II pottery trends and is noticeably greater in quality than prior wares. The White-On-Dark class dominates EM III, the final stage of the early Minoan era. Some places were uncovered that contained more than 90% White-On-Dark ware.

Intricate spirals and other elaborate patterns with realistic characteristics were used in this class. However, not all manufacturers of these goods employed similar patterns at the same time.

Instead, the Minoan motifs became popular over a long period. These innovations foreshadowed the emergence of new classes throughout the Middle Minoan era. EM II and III are distinguished by a refining of the pottery styles and techniques that arose and developed during EM I, and these improvements would eventually set the features for later works of Mycenaean and Minoan pottery.

MM Era Ceramics

With the construction of the palaces and the invention of the potter’s the wheel, ceramics became increasingly popular. This period is well represented by Kamares pottery. The creation of massive palaces dominated the MM era. The manufacture of potted ceramics was centered in these locations. Because of this concentration, artists were more aware of what other craftspeople were doing, and commodities became more uniform in shape and design.

While the pottery grew more uniform in design throughout MM, the products remained extravagant.

The most complex decorations of any prior time arise during the MM era. These patterns were most likely influenced by the Minoan frescoes that appeared throughout the palace period. Although the White-On-Gray class established the beginnings of these Minoan motifs in EM III, the new ornamental approaches of this time had no predecessor.

Around MM IIIA, the workmanship of adorned palace pottery starts to deteriorate, possibly suggesting that it was being substituted with precious metal on the ruling elite’s altars and dining tables.

LM Era Ceramics

Geometric simplicity and monochrome painting define the palace architecture of the region around Knossos. The richness of ornamentation that became fashionable during the MM period was maintained in LM products. The designs and motifs used to adorn ceramics become more intricate and diversified. The Marine Style, Floral Style, Abstract Geometric, and Alternating forms of décor were popular during this period.

Additionally, potted products depicting animals, like bulls’ heads, became fashionable during LM.

These ornamental pieces were painted with trendy designs of the period, resulting in some of the most exquisite Minoan potted products. By the conclusion of LM IB, dark-on-light artwork had overtaken light-on-dark. The concepts and methods that had developed since the Neolithic era were fully articulated in LM pottery. This articulation, however, was not the result of linear evolution. Instead, it was created through a continuous exchange of concepts and processes, as well as a desire to move away from, as well as adhere to, existing manufacturing standards.

Late Minoan art affected Mycenaean art, and there was a reciprocal inspiration, both in the topics utilized in ornamentation and in novel vessel designs.

The Mycenaeans retained the Minoan understanding of the sea by regularly using aquatic shapes as artistic themes. The Marine Style, influenced by Minoan frescoes, includes marine animals, fish, octopuses, and dolphins covering the full surface of a pot against a backdrop of seaweed, rocks, and sponges. By the LM2 era, the painting had lost its “life and flow,” and figurative painting had been relegated to a framed strip around the container body.

Minoan Jewelry

Minoan jewelry has largely been discovered in cemeteries, and until recently, much of it consisted of diadems and hair decorations for women, however, there are also the common varieties of bracelets, rings, and necklaces, as well as many small pieces sewed onto clothes. Previously, gold was the primary material, generally hammered incredibly thin, although it appeared to become scarce later on. With imported copper and gold, the Minoans developed intricate craftsmanship.

Bead bracelets, necklaces, and hair accessories are seen in the Minoan paintings, as are various labrys pins.

The Malia Necklace, a gold pendant depicting bees on a honeycomb, shows that the Minoans perfected granulation. This was ignored by 19th-century robbers of the “Gold Hole,” a royal burial place. Fine chains were created during the EM era and were widely utilized.

Minoan jewelers employed stamps, molds, and eventually “hard soldering” to connect gold to more gold without melting it, which required perfect temperature control.

Cloisonné was utilized, first with shaped stones and then with enamel. Aside from the enormous collection in the AMH, the Aegina Treasure is a notable group in the British Museum, of dubious origin, purportedly discovered about 1890 on Aegina, an island near Athens, but classified as Cretan work from the MM III to the LM era. Figurative work on Minoan artifacts like gold rings, seals, and other jewels was frequently exceptionally beautiful.

Minoan Weapons

Finely engraved bronze weapons have been discovered in Crete, particularly during the LM era, although they are significantly less notable than the relics of warrior-ruled Mycenae, where the famed shaft-grave burials feature many elaborately painted swords and knives. Spears, on the other hand, are mostly utilitarian. Many of these were most likely created on Crete or by Cretans residing on the mainland. Daggers are frequently the most ornately designed, with gold hilts encrusted with gems and the midsection of the blade embellished with a variety of styles.

The most renowned are a couple inlaid with complex sceneries in gold and silver set on a black backdrop, the substance and method of which have been fiercely debated.

These contain long, thin scenes running down the center of the blade, displaying the aggression typical of Mycenaean Greek art, as well as a complexity in technique and figurative iconography that is strikingly novel in a Greek environment. There are several scenarios of lions pursuing and being hunted, striking, and being attacked; the majority are presently housed in Athens’ National Archaeological Museum.

Metalmalerei is another name for the process. It entails combining silver and gold inlays or foils with black and bronze which was once highly polished. The black niello was used as a binder to secure the thin silver and gold foils in place as well as to provide a black color.

The largest and most remarkable, presumably Cretan from the LM IA era, is the Lion Chase Dagger, with a gazelle chase on the other surface.

Helmets, shields, and, by the end of the era, some bronze plate armors are all well-represented in depictions in various media, but there are few surviving examples with significant adornment. Late Mycenaean helmets were frequently adorned with portions of hog tusk and feathers at the top.

Minoan Metal Vessels

Minoan Metal vessels were made in Crete from at least EM II in the Prepalatial era to the Postpalatial era. The earliest were most likely composed entirely of precious metals, but beginning in the Protopalatial era, they were also constructed of arsenical bronze and, later, tin bronze. The archaeological record indicates that most precious metal vessels were cup-shaped, but the collection of bronze vessels was diversified, comprising pans, bowls, cauldrons, basins, pitchers, cups, ladles, and lamps. The vessels’ purposes are unknown, although researchers have postulated various hypotheses.

Bowls were presumably used for drinking, hydria and pitchers for distributing liquids, pans and cauldrons for cooking, and other specialized forms like lamps, sieves, and braziers had more particular roles.

Numerous scholars have proposed that these metal vessels played a significant role in ceremonial drinking rites and communal banquets, with elites using valued bronze and precious metal vessels to demonstrate their high status, authority, and supremacy over lower-status attendees who used earthenware vessels. Metal pots were frequently deposited as grave goods throughout later eras when Mycenaean inhabitants settled in Crete.

They may have signified the individual’s riches and position by referring to their capacity to organize feasts in this form of public burial, and collections of vessels deposited in tombs were likely used for funeral feasting before the burial itself. Extant Neopalatial era vessels are virtually entirely from “destruction settings”; that is, they were buried under the rubble of structures demolished by natural or man-made calamities.

Vessels from the Postpalatial era, after Mycenaean colonization in Crete, on the other hand, are predominantly from burial settings. This represents the shift in burial traditions that occurred throughout this time period.

The relevance is that vessels from previous settlement destruction situations were accumulated accidentally and thus may portray a random collection of the vessel types in public hands at the time, whereas those from subsequent burial settings were specifically chosen and placed, potentially for specialized symbolic reasons that we are unaware of. This implies that the existing vessels from this period are likely to be less indicative of the variety of vessel types in use at the time. Minoan metal containers were mostly made by raising sheet metal, however, some may have been cast using the lost wax process.

According to studies, Minoan metalsmiths usually raised pots with stone hammers without grips and wood metalsmithing pegs. Handles, legs, rims, and ornamental components on many vessels were cast individually and then attached to the vessel. To make bigger containers, several pieces of the sheet were riveted together. Various methods were used to embellish some of the jars. Other bronze containers’ cast handles and rims feature ornamental designs in relief on their faces, while the walls of some jars were worked in repoussé and chasing. Repoussé, decorative rivets, gilding, and inlay of other precious metals material were used to embellish precious metal objects.

What has remained from Minoan art to this day gives insight into the civilization that existed in Crete throughout the Prehistoric period. The Minoan art reflects a happy civilization that was in touch with its surroundings and awed at the perfect order of the natural world. Above all, the discovered artifacts depict people with a strong sense of self-worth and a sharp eye for watching and adapting to their physical surroundings.

Take a look at our Minoan art history webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Minoan Frescoes Differ from Egyptian Frescoes?

The Minoans painted murals to embellish dwellings and palaces, while the Egyptians painted them for burial rooms. Although the Egyptians did not utilize genuine fresco, the Minoans copied some of the color rules of their artwork. Minoan figures were depicted in full profile and styled with exaggerated characteristics such as wider shoulders and relatively slender waists, whereas Egyptian figures were depicted with their torso facing forward and their heads and limbs in profile.

What Are the Characteristics of Minoan Artworks?

Minoan painting is marked by its vibrant colors and curved forms, which give situations life and vigor. Minoan art demonstrates a love of the sea, animals, and plant life, which was employed to create frescoes and ceramics. It also influenced the shapes of stone utensils, jewelry, and sculpture. Wall paintings in the fresco method were prevalent in Minoan painting.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Minoan Art – Learn All About Important Minoan Art Pieces.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 7, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/minoan-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 7 October). Minoan Art – Learn All About Important Minoan Art Pieces. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/minoan-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Minoan Art – Learn All About Important Minoan Art Pieces.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 7, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/minoan-art/.