Négritude Movement – The Francophone Roots of Black Pride

What was the Négritude movement, and why was it so significant? Throughout art history, no change has been achieved without significant rejection of former values and styles. Art history is riddled with all the odds and ends of Western art and cultural values, which have dominated the art world and inspired change among many groups across the visual arts, literature, film, and other modes of creative expression. The Négritude movement was one such cultural proponent of change that marked the congregation of Black thinkers, writers, and cultural practitioners to forge new cultural values that would decolonize the lens of Western ideals and the reassessment of African culture. In this article, you will find all you need to know about this influential movement that stood against assimilation and paved a new path for creatives of color to preserve their individual histories.

Contents

- 1 Decolonizing Western Values: The Négritude Movement

- 2 The Importance of Négritude in the Black Cultural Renaissance

- 3 The Founders of the Négritude Movement

- 4 The Principles of Négritude

- 5 Négritude Literature

- 6 Négritude Art and Music

- 7 The Spread of Négritude

- 8 Criticisms of Négritude

- 9 Legacy of Négritude

- 10 Frequently Asked Questions

Decolonizing Western Values: The Négritude Movement

From revolutionary protest poetry to the decolonization of the material culture of the Western world, the Négritude movement sought to shift the perspective of those who lived primarily from a Western cultural point of view.

The re-establishment of the dignity of African cultures from across the globe dominated the phenomenon of the Négritude movement that sought a change in fields that were otherwise wholly overruled by Western thinking and the long-standing belief in the superiority of European culture.

Below, we will dive into the full history of the Négritude movement, including its significance in the Black cultural Renaissance, the principles of the movement, and important criticisms of the Négritude movement.

What Was the Négritude Movement?

The Négritude movement emerged in the 20th century as a literary movement among African and Caribbean writers as a form of protest against the policy of assimilation advocated by French colonial rule. The aim of the Négritude movement evolved among creatives and thinkers from the Harlem Renaissance to encompass a group of Black artists and writers who sought to critically assess the Western values that shaped the Black experience of many individuals living in colonized countries. Considering the elephant of institutionalized racism, which also thrives at its prime in literature and academic resources, was a pertinent topic of discussion in the Négritude movement. Publications that emerged from the movement included Revue du Monde Noir, which was founded by an informal group of writers, musicians, and intellectuals who held regular salons in France in the 1930s.

At the heart of the movement was Western cultural rejection and the mistreatment of Black people by the French, which was instigated by the concept of assimilation.

The belief in universal equality was largely idealistic and hypocritical since both World Wars had already seen the vast humiliation and mistreatment of Black people who were forced to fight for causes that were not theirs. For centuries, Black communities under colonial rule were bound by slavery and had their cultural values significantly undermined to the point where any critical standpoint from a non-Western experience was negated in favor of the classical Western traditions and ideals of the past, fueled by a widespread superiority complex.

The ambitions of the Négritude movement were focused on prioritizing the intellectual validity of the Black experience and shifting the perspective of the world to re-evaluate their foundational beliefs. One had to thus consider the collective separation of self from “the institution”, which symbolically represented the Western world and Western ideals. The Négritude movement was also described as a desire for political freedom and encompassed all cultural, political, social, and economic values from an African standpoint.

The Négritude movement itself asserted the idea that in the flux of multitudes of Western ideals and cultural structures, there was also a negation of culture from societies that were exploited, and as such, change was required to assert the dignity and preservation of non-Western traditions.

The Origins of the Négritude Movement

When did the Négritude movement originate, and what inspired the collective mission? The origins of the Negritude movement were largely inspired by the Harlem Renaissance in the early 20th century. The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural movement that saw the revival of African-American art, dance, music, literature, politics, and theater originating in Harlem, Manhattan, New York. The movement was also recognized as the New Negro Movement and addressed important themes of Black identity, slavery, and the Black experience of people and communities in the United States. The movement was stifled by the emergence of the Great Depression until the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s.

The spirit of the Harlem Renaissance carried through in the Négritude movement in the 1930s among French-speaking Black intellectuals, poets, and writers who addressed the shared Black experience of stereotyping, discrimination, and oppression. Négritude was an ideological movement that influenced the political structures of many African countries and inspired African independence. The historicization of the Black experience by artists and writers in the 1930s and 1940s was crucial to the development of Black consciousness and validated the lives of many communities and cultures who identified with the experience of being “othered” by academia and society.

The father of the Négritude movement was Aimé Césaire who led the movement as a writer and politician against the injustices of colonial systems in Francophone culture.

The Importance of Négritude in the Black Cultural Renaissance

The impact of the Negritude movement was profound in many ways that highlight the importance of the movement itself on Black communities living in French colonies. The significance of the movement is rooted in its advocacy against colonial inequality and helped establish global pride in African cultures as a response to colonial powers. The movement was also responsible for nationalism and self-pride in many African countries through the production of art, music, and literature authored by Black artists.

The movement brought global attention to the impact of European colonization on Africa and the legacy of cultural racism rife in French colonies. The movement also encouraged the production of African-centric knowledge through traditions, literature, and art that cemented the importance of acknowledging colonized cultures.

The term “Negritude” itself was coined by Aimé Fernand Césaire, Léon Damas, and Léopold Senghor, whose contributions to poetry and politics helped spread the movement and strengthen the Black cultural Renaissance. The formation of Black identities commenced in more ways than the visual arts and encompassed music, literature, poetry, and politics. The Négritude movement was thus crucial to the rejection of colonialism and impacted how colonized peoples viewed themselves. Many literary movements emerged from Négritude, which responded to global politics.

The Founders of the Négritude Movement

Behind every movement are a few key players who help revolutionize its mission and drive real-world impact. At the forefront of the Négritude movement were three primary figures, who we will introduce below.

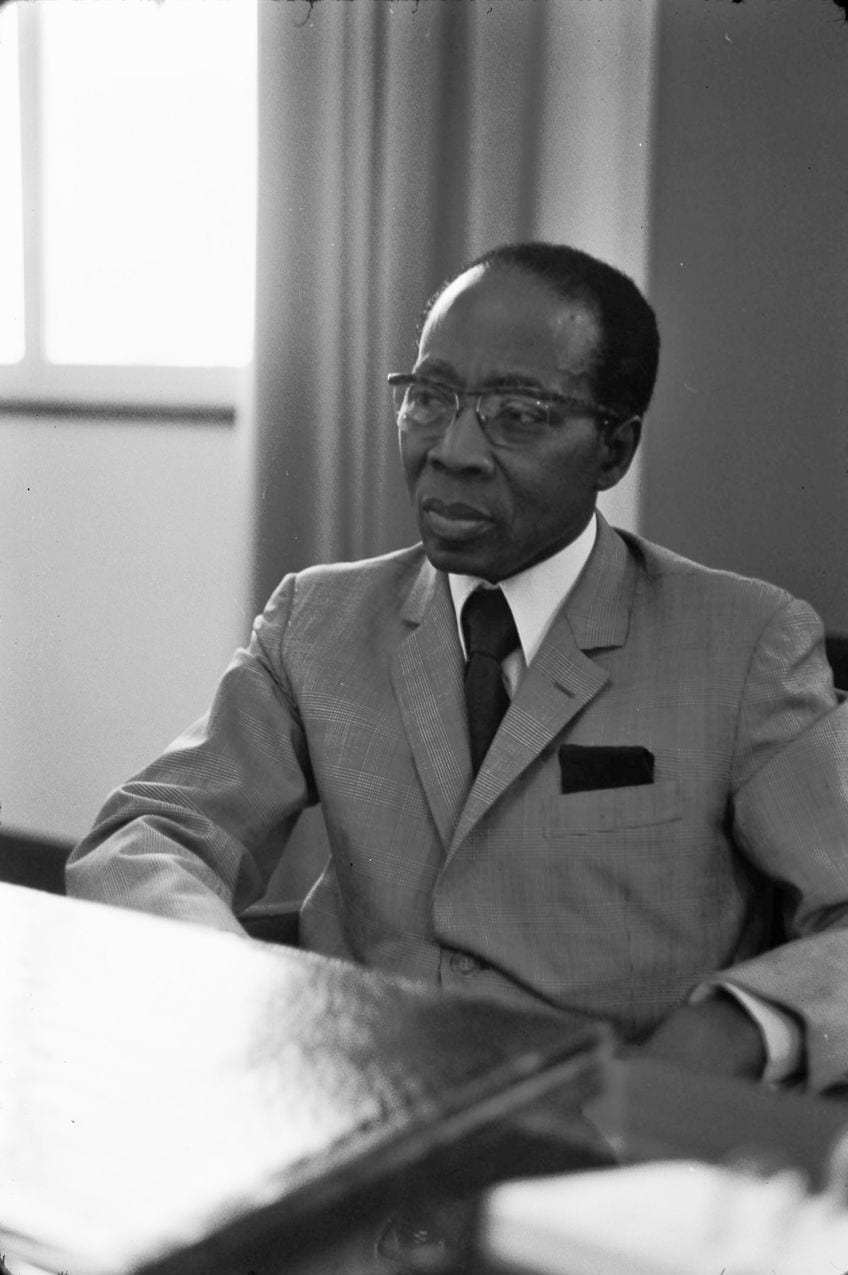

Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906 – 2001)

| Name | Léopold Sédar Senghor |

| Date of Birth | 9 October 1906 |

| Date of Death | 20 December 2001 |

| Nationality | French-Senegalese |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Négritude movement, African Socialism, cultural theory, inclusive Humanism, race, and identity |

| Famous Publications |

|

Léopold Sédar Senghor was among the first three leaders of the Négritude movement who was an African Socialist and theorist. The Senegalese theorist was also a poet and politician who became the first president of Senegal in 1960. Senghor advocated for civil and political rights across French colonies and argued that French-African citizens would be much better off without the interference of the French structure. Senghor also established Senegal as a single-party state, which banned all rival political parties.

The famed political leader was also awarded the International Nonino Prize in Italy in 1985 and had since been considered one of the most important 20th century-African intellectuals. In 1947, Senghor also established the journal Présence Africaine, which published works authored by African thinkers and was crucial to the spread of Négritude.

Senghor believed that African culture had much to contribute to European thought and worked towards a theory of culture led by inclusive humanism, dialogue, and reciprocity.

Léon-Gontran Damas (1912 – 1978)

| Name | Léon-Gontran Damas |

| Date of Birth | 28 March 1912 |

| Date of Death | 22 January 1978 |

| Nationality | French |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Négritude movement, racism, colonial culture, language, oppression, Black identity, and internalized racism |

| Famous Publications |

|

Léon-Gontran Damas was another co-founder of the Négritude movement who was best known for his contribution to French poetry and politics. Damas adopted the pseudonym Lionel Georges André Cabassou and schooled at the Lycée Victor Schoelcher, where he gained acquaintance with Aimé Césaire. In 1929, Damas moved to Paris and studied law alongside other subjects such as anthropology and literature, which fueled his passion for politics.

Damas was later introduced to Leopold Senghor, and by 1935, the three famous founders co-published the L’Étudiant Noir magazine, which became the foundational piece of literature for the Négritude movement.

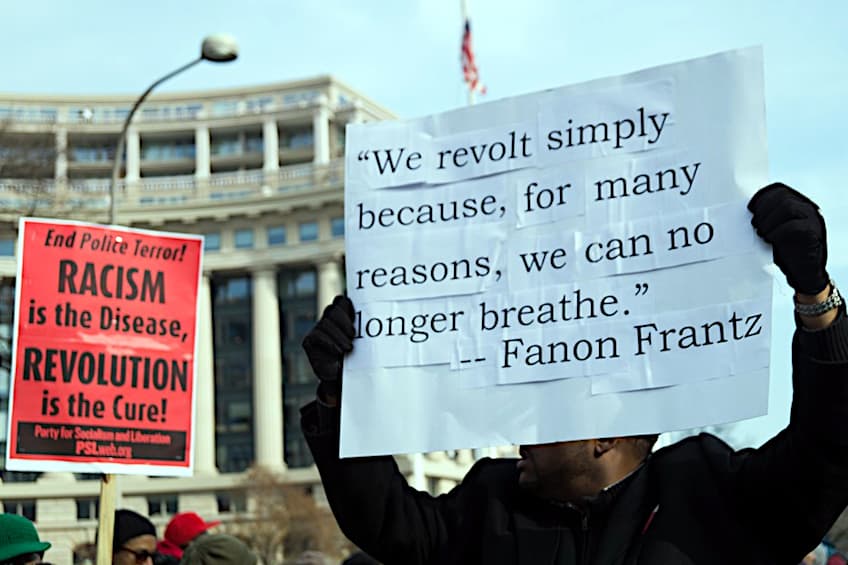

Damas was celebrated for his unique poetry style, which discussed themes of issues in colonial culture, racism, internalized racism, and other diasporic issues, which later became foundational topics for writers like Frantz Fanon and the notion of the colonized personality in Black identity.

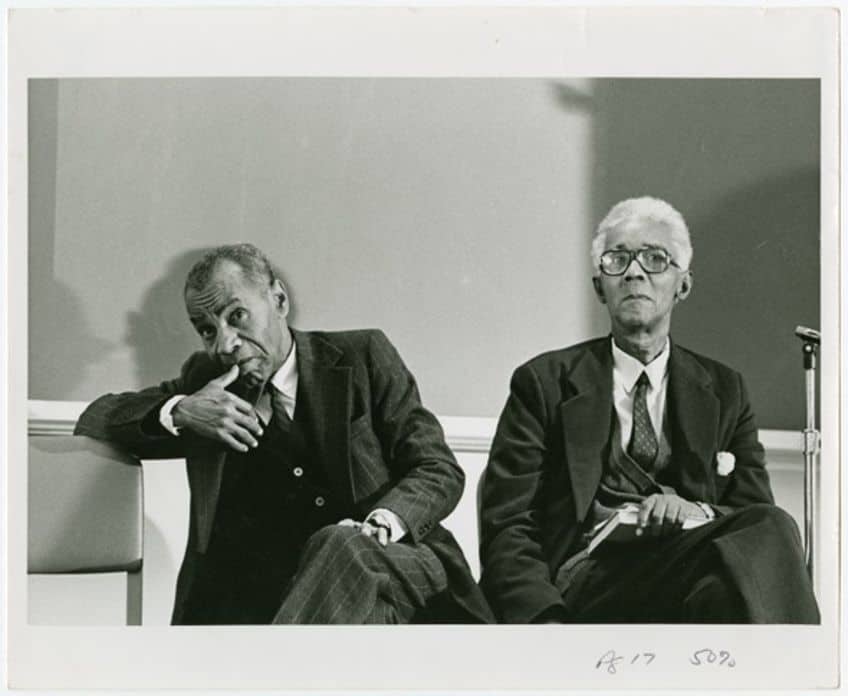

Aimé Césaire (1913 – 2008)

| Name | Aimé Fernand David Césaire |

| Date of Birth | 26 June 1913 |

| Date of Death | 17 April 2008 |

| Nationality | French-Martinican |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Négritude movement, Black identity, cultural identity, politics, race, colonialism, and slavery |

| Famous Publications |

|

French poet and leader of the Négritude movement, Aimé Césaire, was one of the three pioneers of Négritude who coined the term “Negritude” as a movement. Césaire was a French-Martinican politician who is recognized as the former President of the Regional Council of Martinique and is celebrated as an icon who helped restore Black identity to the world. Césaire attended the University of Paris and was also a playwright who produced many theatrical works that addressed themes of anger toward colonial forces, painful memories associated with slavery, and the positioning of the West Indies within the global pan-African environment.

Unlike many Martinicans, Césaire had the opportunity to learn how to read and write French from a young age. Among his most important publications include Lost Body (1986), which featured illustrations by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, and Return to My Native Land (1969). His home country was the island of Martinique, which is located in the Eastern Caribbean Sea and was colonized in 1635. Today, the island remains a possession of France.

The Principles of Négritude

The Négritude movement was founded on a set of principles that made evident the impact of colonialism on African cultures across the world. Below, we will dive into the primary principles of the movement and the key details of each principle.

Embracing Black Identity

At the forefront of the Négritude movement was the establishment of Black identity, which sought to validate the experiences and values of African cultures. What is Black identity? Black identity, as it pertains to the Négritude movement, was a collective analysis and identification of identity introduced by Black intellectuals such as Aimé Césaire, who paved the way forward for many African artists, writers, and intellectuals to consider the roots of their identities amid systematic oppression.

Césaire’s use of the term “Négritude” in the context of the movement was aimed at affirming the heritage and culture of African societies. Césaire first engaged with the term in his poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal, which was published in 1939 and described his negritude as his Black identity and a powerful attribute.

According to Césaire, negritude was the recognition of the fact that one is Black, followed by the acceptance of Black culture, history, and destiny. With the wake of Black identity also came the denouncement of white narratives and the birth of diasporic Black consciousness. Through Césaire’s poetry, Black identity has been historicized and recognized outside of the Western gaze and cemented the Black experience as a historical reality.

The Rejection of Colonialism and Racism

The primary driving force behind the Négritude movement was the rejection of colonialism and racism through the assertion of Black identity, history, and experience across multiple disciplines. “Black I am, and Black I will remain” was a statement by Césaire that solidified his identity in the reality of the Western world, whose history was pillaged and colonized for the benefit of European and Western civilizations. The struggles that many Black intellectuals faced at the time boiled down to racism and institutional racism toward people of color, whose histories were overlooked in favor of their white counterparts.

It is important to remember that the Négritude movement emerged from the context of French-speaking African communities who were frustrated by the dehumanizing and culturally disorienting policy of assimilation proposed by the French.

Assimilation was a French colonial policy that sought to transform African men into French citizens through education. The policy essentially imposed French culture onto Black societies to spread French culture and enable Black people to be accepted and treated with equality. This false promise of social equity was never a realistic policy since it was inherently racist and negated the idea of Black consciousness and culture itself while asserting the superiority and importance of French culture.

Promoting Pan-Africanism

It is important to note that the foundations of the Négritude movement are different from that of Pan-Africanism. The Négritude movement was literary-cultural while Pan-Africanism describes the global political union, which emerged in the first quarter of the 20th century. The aim of Pan-Africanism was a widespread announcement of the rejection of the colonial view that Black people were inferior.

The term Pan-Africanism was first coined by Henry Sylvester Williams in 1900 with the idea originating around the abolitionist events of 1787. Scholars, however, settle on the 15th century as the origin of Pan-Africanism, which flourished in social thought and action with the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism.

Movements like the Harlem Renaissance proposed a new form of Black identity that was not defined by the European binary but emerged from authentic cultural values and histories shared by Black cultural agents. The Négritude movement on the other hand was led by a group of literary intellectuals who sought to correct the notion that Black people were inferior and aimed to create a truer perspective and understanding of Black identity. The notions of Black identity and personality in Pan-Africanism that were represented in Négritude were “symbolic of a subjective rehabilitation” of such identity where the idea of “Blackness became the source of pride” instead of aversion. In 1914, the United Negros Movement was founded, which marked the beginning of Pan-Africanism and was led by Marcus Garvey.

Henry Sylvester Williams was among the first to hold a Pan-African conference and highlight the idea of African countries uniting to fight against colonialism. Since 1919, many Pan-African conferences have been held across the globe to navigate the issues of neo-colonialism, imperialism, and the recognition of people with African origins. The Négritude movement was thus an intellectual stimulation of the recognition of a specific Black identity about the dominant Western cultures, which almost brainwashed mass cultural groups into negating their histories.

The Négritude movement was a revivalist movement that promoted African subjectivity.

Négritude Literature

There are many important publications to review when examining Négritude literature and its most impactful works. Below, we will outline the most prominent pieces of poetry, novels, and essays authored by the leading Négritude figures.

Poetry

Leon Damas was considered a Pan-African intellectual and poet who was best known for his poem Black Label. His poem was one of the most famous examples of Negritude poems that presented the idea of the “inescapable intellectual imprisonment” that many Black intellectuals found themselves in. Damas also highlighted that Black subjectivity reached its essence through the negation of the “other”. He also suggests, through his poem, that the positive resurrection of Black identity emerges through a revolt against colonial logic, which had for centuries disabled Black people.

Damas used strategies like discourse reversal to de-subjectify the villain (the colonizers) to reacquire subjectivity for the dehumanized “other”.

Many famous examples of Negritude poems were authored by figures such as Léopold Sédar Senghor, Birago Diop, and David Diop, who used Négritude philosophy to highlight topics such as Western colonialism in Africa, a nostalgia for Africa, and a critique of African individuals who imitated Western culture.

Novels

There are a multitude of books that discuss the nuances of the Négritude movement through the lens of Négritude supporters. Books such as Black Skin, White Masks by Frantz Fanon is among the most popular choice for those researching the inner workings of Négritude and Black subjectivity.

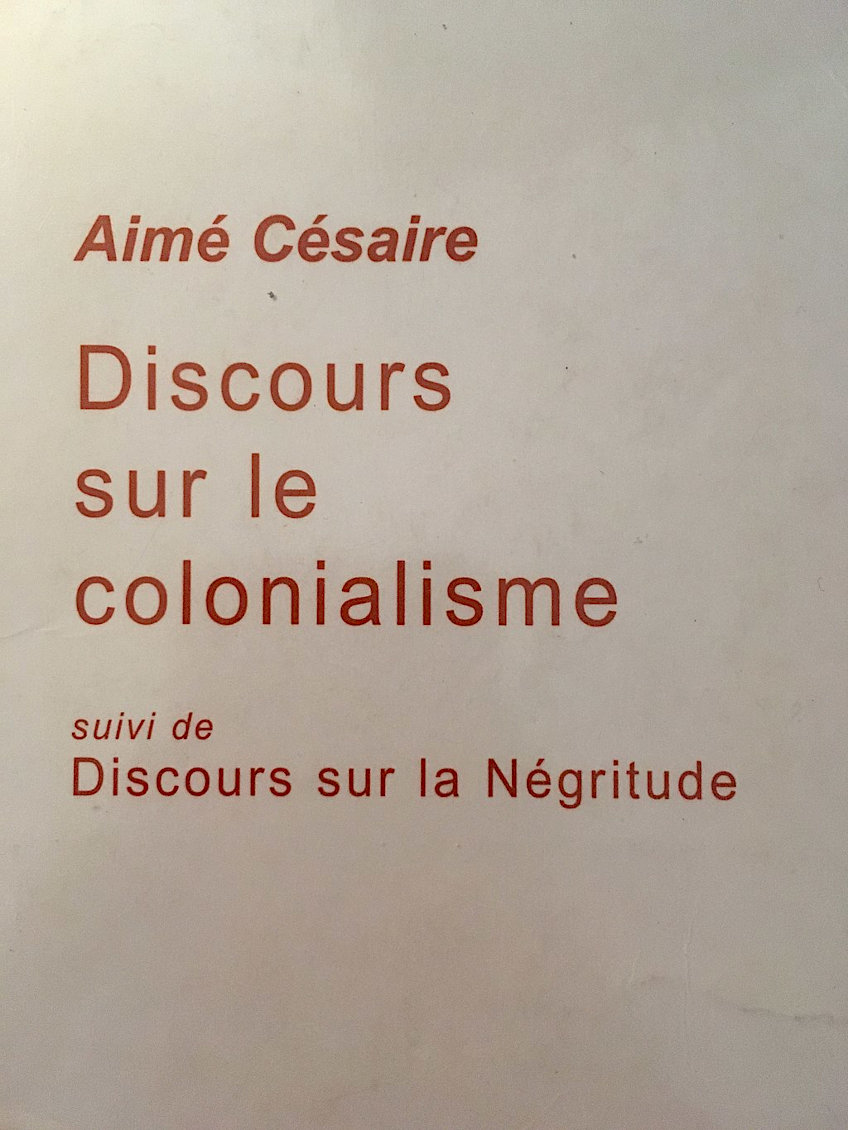

Other important books include Notebook of a Return to the Native Land (1939) and Discourse on Colonialism (1950) by Aimé Césaire, The Revue du monde noir (1931–1932) by Louis -Thomas Achille, and Batouala (1921) by René Maran. Batouala was one of the most influential novels of the Négritude movement that also won the Prix Goncourt literary award. René Maran was the first Black author to win the award.

Essays

Orphée Noir (1948) was one of the first and most impactful essays written about the Négritude movement. The essay was penned by Jean-Paul Sartre and became the introduction for a Francophone publication by Léopold Senghor, called Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache (1948).

Sartre’s essay was an analysis of the movement and offered a deep critique of it by characterizing the movement and essence of négritude as “the polar opposite of racism.

His view of the movement was that it was an “anti-racist racism” that was vital to achieving racial unity. Essays such as Bonjour et Adieu à la Négritude (1980) by René Depestre, were significant in establishing subjective Black identities related to the diasporic experience of Caribbean cultures.

Négritude Art and Music

Despite the Négritude movement originating in the literary sector, its influence and reach spread to the visual arts and music, which resulted in a vast array of complex genres, artists, and narratives of Black diaspora across the world. Below, we will look at the ways that Négritude emerged in visual art and music, to fully grasp the influence of the movement.

Visual Art

While the Négritude movement began as a literary movement, its ideals and philosophies infiltrated the visual arts and soon Paris became the origin of Négritude art. The global Négritude movement manifested in the visual arts among many Black artists who traveled from the Caribbean and Africa to study in Paris and convene at the Clamart tea shop, which became the base for Négritude discussions. Artists such as Aubrey Williams, Uzo Egonu, and Frank Bowling joined forces in a critical alliance against imperial art and imperialism itself, which resulted in the birth of modern Avant-Garde art.

Négritude artists advocated for Black culture in light of the surge of modernity and a recognition of the struggles of the past. Among the most impactful artists of the Négritude movement were figures like Ben Enwonwu, a famous Nigerian sculptor and painter who received critical acclaim and championed the path forward for Modern African art and its recognition in the global art stream. Enwonwu was also a prolific art critic and writer who recognized the intellectual barriers that Western critics associated with African art in terms of labeling African-made art styles as “primitive.

Cuban artist Wilfredo Lam was another celebrated figure in Négritude art who combined the narratives of African culture with Surrealism and Cubism while drawing from South American belief systems, modernist trends, and Socialism.

Lam was taught by the same educator as Salvador Dalí and was recognized for his hybrid figural paintings of part-human, part-animal, and part-vegetable creatures. Lam thus invented a unique style encompassed by his subjective experience of Afro-Cuban cultures.

Music

Musical references have been an integral part of Négritude literature, often cited in Pan-Africanist literature that described music as the uniting medium through which people could connect to the continent. The Festival Mondial des Arts Négres was the first major Pan-African event that prioritized sound and musical performance as the main tool for communicating the future of postcolonial Black cultures.

While the early events held weight in the newfound independence of Africa, it was soon overpowered by the many civil rights struggles of African Americans and South Africans who faced harsh oppression from their non-black leaders.

The Spread of Négritude

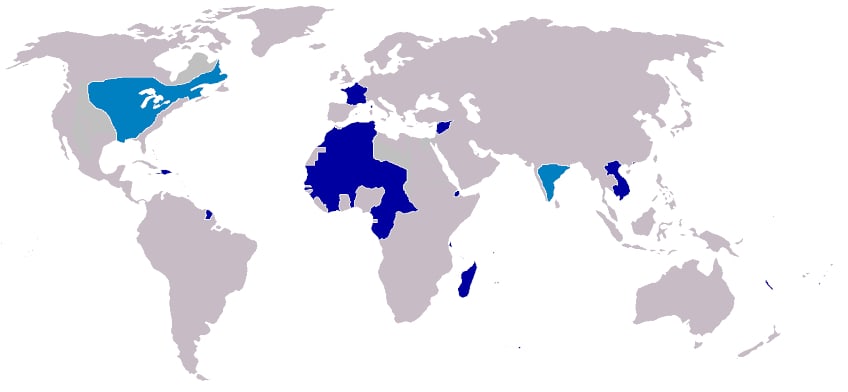

The influence of the Négritude movement as well as the Harlem Renaissance and global Pan-Africanism were profound in fostering the recognition of Black cultures, Black identity, and the beginning of the postcolonial decolonization of institutional systems. Négritude in Paris sparked African independence and impacted how colonized peoples viewed themselves.

The history of Négritude in areas such as Latin America can be recognized in the 15th-century Spanish and Portuguese conquests and the details of the African diaspora in Latin America remain a complex path to pinpoint due to its deep history of oppression and cruelty toward indigenous nations.

Across the Caribbean and Latin America, there has remained a stark resilience in the cultures that developed their multi-ethnic identities through shared spaces. During the age of Spanish-American Modernism, many French Caribbean, and Spanish writers started to detach themselves from the ideals of European thought and identity more closely to West Indian cultures. Leaders of this period included figures such as Nicolás Guillén, Jacques Roumain, and Luis Palés Matos. The British Caribbean developed its own national publication in the mid-1940s through novels such as New Day (1949) by Vic Reid and A Brighter Sun (1952) by Samuel Selvon.

Criticisms of Négritude

While the Négritude movement emphasized the immense value of African art and music, one can also consider the concurrent role of archaeology that established Africa as the birthplace of humanity. After 1960, the Modern generation of Black writers and philosophers united to propose many points of debate surrounding the movement and the ideas presented in Senghor’s literature. Many have expressed their disappointment for the shortcomings of the Négritude movement and their promised welfare that was deemed “unsuccessful”.

During the conference of Alger, which took place in 1969, experts on Caribbean and African literature marked the end of the Négritude movement with debates on the philosophies of Black Francophone cultures.

Négritude and Essentialism

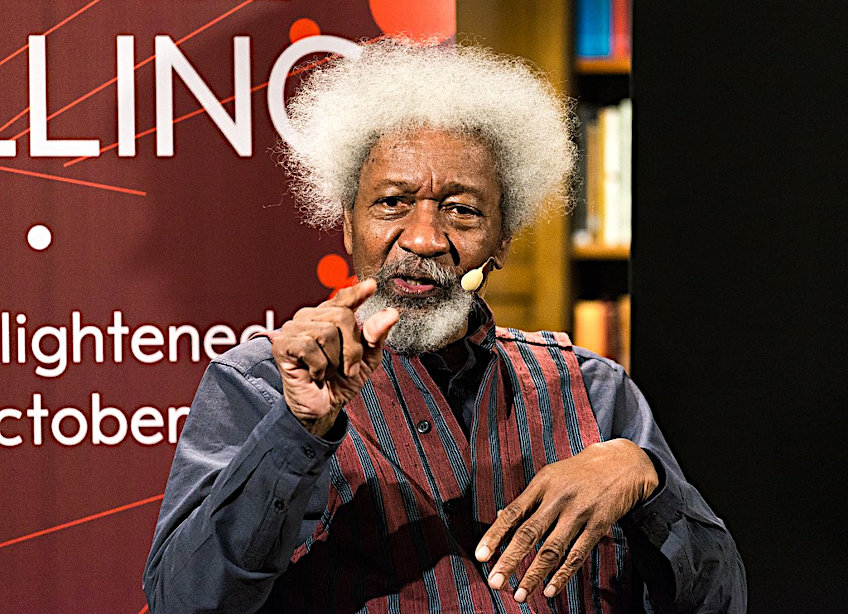

The 1980s saw the emergence of concepts related to the “creolness” of the Caribbean people and the notion of national literature. Négritude was criticized from all angles and was ridiculed by figures like Wole Soyinka, who compared the movement to “Tigritude”, claiming that a tiger does not announce itself, instead, it simply pounces.

This direct criticism of the movement implied that there was more speaking than action and perhaps the image of Négritude falsified the world’s image of Africa itself. The essentializing of Africa into a continent and unified consciousness was the ultimate form of negation of the diaspora it claimed to represent. Scholars have criticized Négritude for its narrow presentation of Africa as a pure continent filled with innocence and naked, pristine beauty.

Négritude on Gender

Famous Négritude publications like Présence Africaine have been criticized for their lack of representation of women in the Négritude movement. One of the crucial points of concern was the issue of labor to sustain life and the lack of recognition of the idea that where labor occurred, there was always gendering. Négritude women such as Dorothy Brooks, the Nardal sisters, and Christiane Yandé Diop examined the notions of re/productive labor between intellectuals and other figures of the movement who operated without such a title. Of important note is that the 1956 Congress of Black Writers and Artists had 63 delegates, none of whom were women, and critically significant since the gathering was crucial to the adoption of Black culture.

The issue raised in the case of women in the Négritude movement and their recognition was the matter of “who could be counted as an intellectual?”, and as history suggested, women were certainly negated to a significant degree when outlining the foundations of Black identity.

Women of the Négritude movement contributed to the publication of literature and authorship of critical philosophies from their homes. Figures such as Yandé Diop were major contributors to the planning team management and success of the congress. Labor in this critical inquiry referred to the editorial, administrative, and logistical tasks of the Congress.

Legacy of Négritude

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Négritude movement influenced the visual arts and sparked the emergence of the Black Arts movement. The Black Arts movement was an art movement led by African American artists and aimed to assert Black pride through various efforts related to establishing new institutions, engaging Harlem Renaissance artists, and promoting a state of activism in the arts.

The movement is famously recognized as the “spiritual sister of Black power” and evoked the diasporic experiences of African American cultures in the United States.

Pioneering artists such as Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Aaron Douglas, and Hale Woodruff. The founder of the Black Arts movement is recognized as Amiri Baraka (also known as Leroi Jones), who was a renowned playwright and poet, responsible for the establishment of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School in 1965.

African Independence Movements

Throughout the 20th century, the world saw a series of African Independence movements that were sparked by the Négritude movement. Between 1952 and 1960, British-led Kenya saw an insurgency by rebels against the British colonists and was led by the Kikuyu culture. Long before this, the French colony in Algeria saw resistance in the 19th century under the leadership of Amir Abd Al-Qadir. The primary mission of this rebellion, however, was centered on Islam as opposed to nationalism. The rebellion lasted nearly two decades until Algeria’s submission to France under the Tijaniyya Brotherhood.

By World War I, opposition to French occupation was more of a challenge and many Algerians were drafted to fight for the French. For many people in Algeria, Islam was a means to escape the French colonists and their policies.

In 1945, the tensions grew rife and Algeria witnessed a massacre in Setif during their independence fight. The struggles for independence were not without bloodshed. After World War II, the French army murdered around 45,000 Algerians, which caused a massive uproar among nationalists and eventually led to the Algerian War (1954–1962).

The war saw thousands of women enroll in deadly missions, posing as spies, cooks, and launderers, with an estimated 11,000 women who partook in bombing activities. In 1962, Algeria won its independence after many deaths and a peace accord with France. Other prominent African Independence movements emerged, including the Portuguese Colonial War in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau, as well as the South African Border War in Namibia.

The significance of the Négritude movement as an ideology and the criticism of its origins and philosophies are imperative to the ongoing development and understanding of what it means to establish a postcolonial Black identity. We hope that this valuable and rich history of Négritude will inspire you to engage in such critical and relevant discourses.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Negritude and Négritude?

The ideological and literary movement aimed at rejecting colonialism was known as the Négritude movement, and was specific to French-speaking African and Caribbean students in Paris who sought to reclaim Black identity, culture, and consciousness. The term Negritude emerged from the original French term, Négritude, which described the rejection of assimilation through a framework of critiques established by writers, poets, politicians, and academics of Francophone backgrounds.

Is Négritude Still Relevant Today?

The 1930s Négritude movement remains a relevant point of study and reference in the critical discourse of the Black Lives Matter movement, which expands the original establishment and development of Black identity and forms of systemic oppression.

How Did Négritude Influence Black Culture in the United States?

Négritude as a concept heavily influenced the birth of many significant movements in the United States and the rest of the world through anti-racist activism. The solidification of Black culture and its recognition across the United States were seen in movements such as the Harlem Renaissance, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the implementation of civil rights legislation, Black Power, and the Black Lives Matter movement. The increased recognition of Black culture and the gradual decline of colonial stereotypes against Black people progressed in waves over the 20th century, and continue to gain strength today.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Négritude Movement – The Francophone Roots of Black Pride.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 7, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/negritude-movement/

Anthony, J. (2023, 7 November). Négritude Movement – The Francophone Roots of Black Pride. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/negritude-movement/

Anthony, Jordan. “Négritude Movement – The Francophone Roots of Black Pride.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 7, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/negritude-movement/.