Persian Art – A Deep Dive into Ancient Persian Arts

Iranian art, also known as Persian art, is known for having one of the most illustrious art heritages throughout human history. From ancient Persian art, right up to today – the style has influenced many mediums, such as Persia paintings, Persian sculptures, and Persian architecture, to name but a few. The style of the ancient Persian paintings and sculptures was influenced by neighboring cultures and it, in turn, influenced them. The overarching term for art from this region, in general, is referred to as Islamic art.

Contents

Discovering the Beauty of Persian Art

The remaining monuments of the Persian art of antiquity are noteworthy for their representation of a tradition that focused on the human form and animals. Persian art tended to put a greater focus on the portrayal of people than Islamic art from other countries, however, for religious reasons, monumental examples, particularly in sculpture, were typically avoided. The typical Islamic style of geometrically orientated dense adornment evolved in Persia into a beautifully styled and cohesive aesthetic.

The aesthetic incorporated plant patterns with Chinese themes and frequently animals that were depicted at a relatively small scale compared to the vegetation encircling them.

Ancient Persian Arts

Susa’s earliest settlers built a temple on a massive mound that rose above the flat surrounding environment approximately 6000 years ago. The unique character of the site may still be seen in the craftsmanship of the ceramic objects laid as gifts in a thousand or more grave sites around the temple. Around two thousand vessels were retrieved from the graveyard, most of which are currently housed in the Louvre.

The discovered vessels provide compelling indications of their makers’ aesthetic and technical skills, as well as clues about the structure of the civilization that designed and created them.

Susa’s painted ceramic jars produced in the early style are a regional variation of the Mesopotamian Ubaid pottery traditions, which expanded over the Near East around the fifth millennium. Objects such as beakers, dishes, and goblets were found at the burial site too, indicating that the inhabitants believed that the deceased would need these objects in the afterlife.

Others are coarse cooking bowls with simple rings drawn on them and were most likely the grave objects of less wealthy individuals, teenagers, and maybe infants.

The ceramics of this period are skillfully handcrafted. Although a slow wheel was used, the irregularity of the containers and the inconsistency of the surrounding bands and stripes suggest that the majority of the production was performed freehand.

Luristan Bronze Persian Sculptures

Luristan bronzes are tiny cast artifacts adorned with Iron Age bronze Persian sculptures that have been discovered in significant quantities in west-central Iran. They can be found on a wide range of ornaments, weaponry, implements, horse fittings, and a limited range of containers, and those discovered in documented excavations are almost always unearthed at burial sites. The identity of the individuals who created them is unknown, however, they may have been Persian, maybe linked to the present Lur tribe who named the region.

The bronzes, like the associated Scythian art metalwork, are flat and employ openwork.

They reflect the arts of a nomadic people for whom all things had to be lightweight and portable, and swords, brooches, horse-harness fittings, pitchers, and other fittings were richly ornamented across their surfaces. Depictions of animals, particularly sheep or goats with enormous horns, were popular, and the patterns and designs are distinct and innovative.

The “Master of Animals” theme, which depicts a person positioned between and grabbing two hostile animals, is popular but heavily stylized.

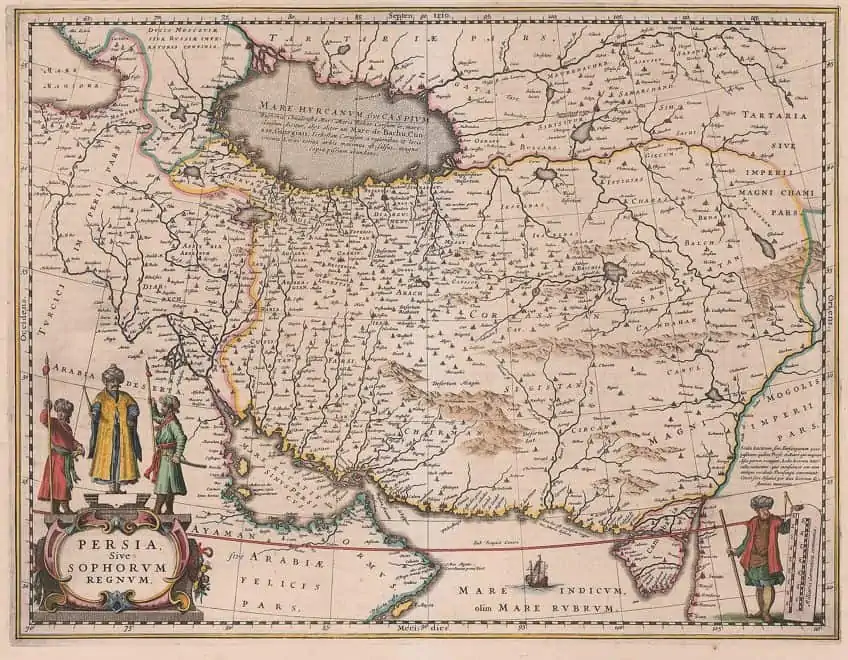

The Achaemenids

The Achaemenid Empire was founded by Cyrus the Great and was the first Persian Empire. Metalwork, Frieze reliefs, palace ornamentation, excellent workmanship, and gardening are examples of Achaemenid art. The animal-headed Persian columns and other Persepolis artworks are the most frequent remnants of palace art. Although the Persians brought artists from all around their territory, with their many techniques and methods, they created a synthesis of a new distinctive Persian style.

Cyrus the Great inherited a rich ancient Iranian legacy; for example, the beautiful Achaemenid gold craftsmanship was created in the tradition of previous civilizations.

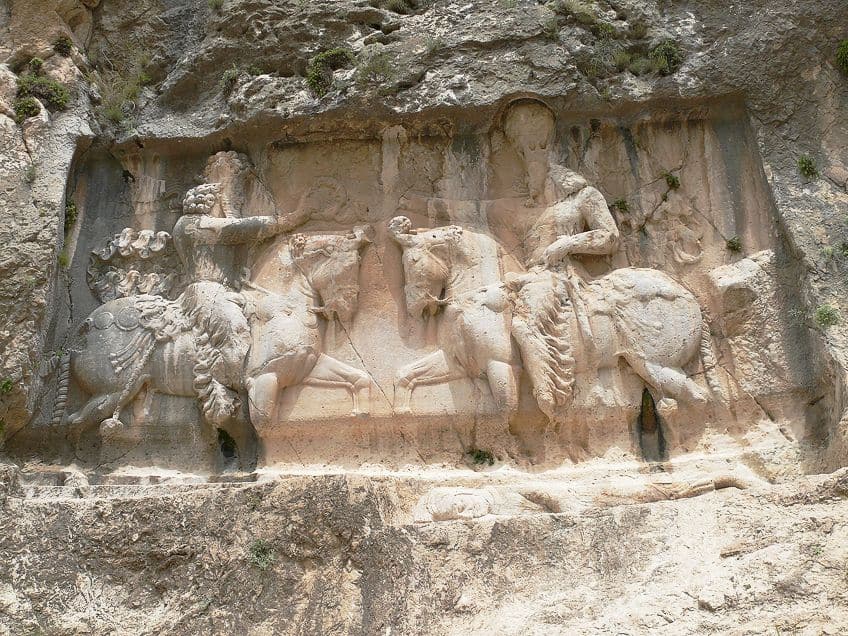

Rock Relief Art

The massive carved rock reliefs, which were usually set high by a road and beside a water source were a prominent form in Persian art and were generally used to honor the ruler and establish Persian dominance over a specific region. Persian emperors regularly flaunted their authority and successes until the Muslim invasion eliminated images from such monuments; a slight resurgence emerged later during the Qajar dynasty.

Behistun is unique in that it featured a massive and famous inscription that, similar to the Egyptian Rosetta Stone, repeated its content in three separate languages, all of which are written in cuneiform: Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite.

This was crucial in the development of contemporary interpretations of these languages. Other Persian reliefs are often devoid of inscriptions, and the rulers concerned are frequently only vaguely identifiable. In the instance of the Sasanians, the issue is addressed by their tradition of displaying a new type of crown for each monarch, which can be distinguished from their currency.

The Parthians

Parthian art was a hybrid of Hellenistic and Iranian traditions. From 247 BC until 224 AD, the Parthian Empire ruled over what is now Greater Iran and multiple areas outside of it. Parthian sites are generally ignored in excavations, and Parthian strata can be challenging to differentiate from those around them.

As a result, the research conditions and extent of understanding of Parthian art are minimal.

Dating is problematic, and the most significant remnants come from the empire’s outskirts, such as Hatra in modern Iraq, which has provided the greatest number of Parthian sculptures ever excavated. Even following the Parthian dynasty, artworks in the Parthian style persisted in the surrounding territories for some years. Even in narrative depictions, people face the audience rather than each other, foreshadowing the art of the Late Antiquity, medieval Europe, and Byzantium periods.

Special attention was given to the intricacies of clothing, which were covered with ornate motifs, most likely embroidered, including big figures.

The Sasanians

The Sasanian dynasty ruled what is now Iraq, Iran, and most of the country to the north and east of modern-day Iran for 400 years. It ruled over most of Anatolia, the Levant, and portions of Arabia and Egypt at times. It marked the beginning of a new age in Mesopotamia and Iran, which was based on Achaemenid customs in many respects, including the period’s artwork. Nonetheless, additional influences on their artwork came from as far away as the Mediterranean and China.

The Sasanian art that has survived is mainly apparent in its reliefs, architecture, and metalwork, however, there are also a few surviving ancient Persian paintings from what appears to have been a large industry.

Interior plaster reliefs, of which only pieces have remained, most likely exceeded stone reliefs in number. In comparison to the Parthian period, free-standing sculptures fell out of style throughout this era. Ancient Sogdia and Panjakent in modern Tajikistan, which was barely within the grip of the central Sasanian Empire, are two of the rare places where murals have survived in abundance. The ancient city was deserted in the decades following the Muslims’ final capture of the city in 722 and has since been thoroughly excavated.

Large portions of wall paintings from the palace and private dwellings have survived and are currently largely housed at the Hermitage Museum or Tashkent. They took up entire rooms and were complemented by a multitude of wood reliefs. With enthroned monarchs, wars, feasts, and beautiful ladies, the topics were comparable to other Sasanian artworks, and there are images of both Indian and Persian epics, as well as a diverse blend of deities. The Roman glass technique was continued and enhanced by the Sasanian glass.

It appears to have been accessible to a broad spectrum of the populace in simpler versions, and it was a favorite luxury export to China and Byzantium, even emerging in aristocratic graves from the time in Japan.

The Sogdians

The Sogdians are most known today for their Persia paintings, but they also had exceptional architecture and sculpture. The Sogdians were extremely skilled at metallurgy, and their works influenced the Chinese, who were among their customers alongside the Turks. Sogdian metalwork can be mistaken for Sasanian metalwork, and some researchers continue to be confused about the two. They diverge, however, in style, form, and iconography.

Several characteristics of Sogdian metalwork have been identified due to the works of archaeologist Boris Marshak.

Sogdian products are less substantial than Sasanian containers, and their shape varies from the Sasanian, as do the processes used in their fabrication. Furthermore, Sogdian products have more dynamic aesthetics. The Sogdians lived in intricate architectural structures that mimicked their temples.

These locations were adorned with magnificent paintings, a skill that the Sogdians mastered. They did prefer to create paintings and wood sculptures to decorate their own homes. Sogdian murals are not only vivid, vibrant, and beautiful, but they also convey the history of Sogdian life. They emulate, for instance, period clothing, game equipment, and harnesses. They also represent sagas and tales with Near Eastern, Iranian, and Indian themes.

Sogdian religious art depicts the Sogdians’ religious beliefs, and this understanding is mostly gathered through paintings and grave sites. It is possible to “feel the vitality of Sogdian life and creativity” through these relics.

The Early Islamic Period

Geometric Islamic architectural embellishment in tiling, stucco, brick, and carved wood grew intricate and polished and was arguably the principal style of Iranian art that could be viewed by the whole people, with other types confined to the private domains of the affluent. Carpets are mentioned in various descriptions of life from that period, but none have survived; they were likely mostly a regional folk art at the time.

Presumably, for a sophisticated metropolitan market, finely decorative metalwork in copper alloys was made.

Silver and gold versions are thought to have existed but were primarily repurposed for their precious metals; the few survivors were mostly trafficked north for furs and subsequently buried as burial goods in Siberia. Sasanid imagery of heroes on horseback, hunting scenarios, and sitting monarchs with attendants survived in ceramics and metalwork, which was now typically surrounded by geometrically complex and calligraphic ornamentation.

The exquisite silk fabrics that were a major export from Persia also retained the animal, and occasionally human, representations of their Sasanid forebears.

Persian Art Forms

Weaving carpets is an important component of Persian art and culture. The Persian carpets stand out among the Oriental carpets manufactured by the other countries in the region due to the diversity and complexity of their designs. A Persian miniature is a little painting on paper that is either a book illustration or a distinct piece of art that is meant to be stored in a collection of similar works known as a muraqqa. Then there are the Persian sculptures, ceramics, books, and other forms of Iranian art. Let’s take a deeper look at them.

Carpets

Nomadic tribes, rural and urban workshops, and royal court manufactories all worked together to weave diverse styles of Persian rugs and carpets. As such, they embody diverse, concurrent lines of traditions and reflect Iran’s heritage and its varied peoples. Carpets woven at the Safavid palace manufacturers of Isfahan throughout the 16th century are renowned for their rich colors and artistic designs and are now held in galleries and private collections across the world.

Their designs and patterns established an aesthetic heritage for palace factories that was maintained throughout the Persian Empire until the final royal dynasty of Iran.

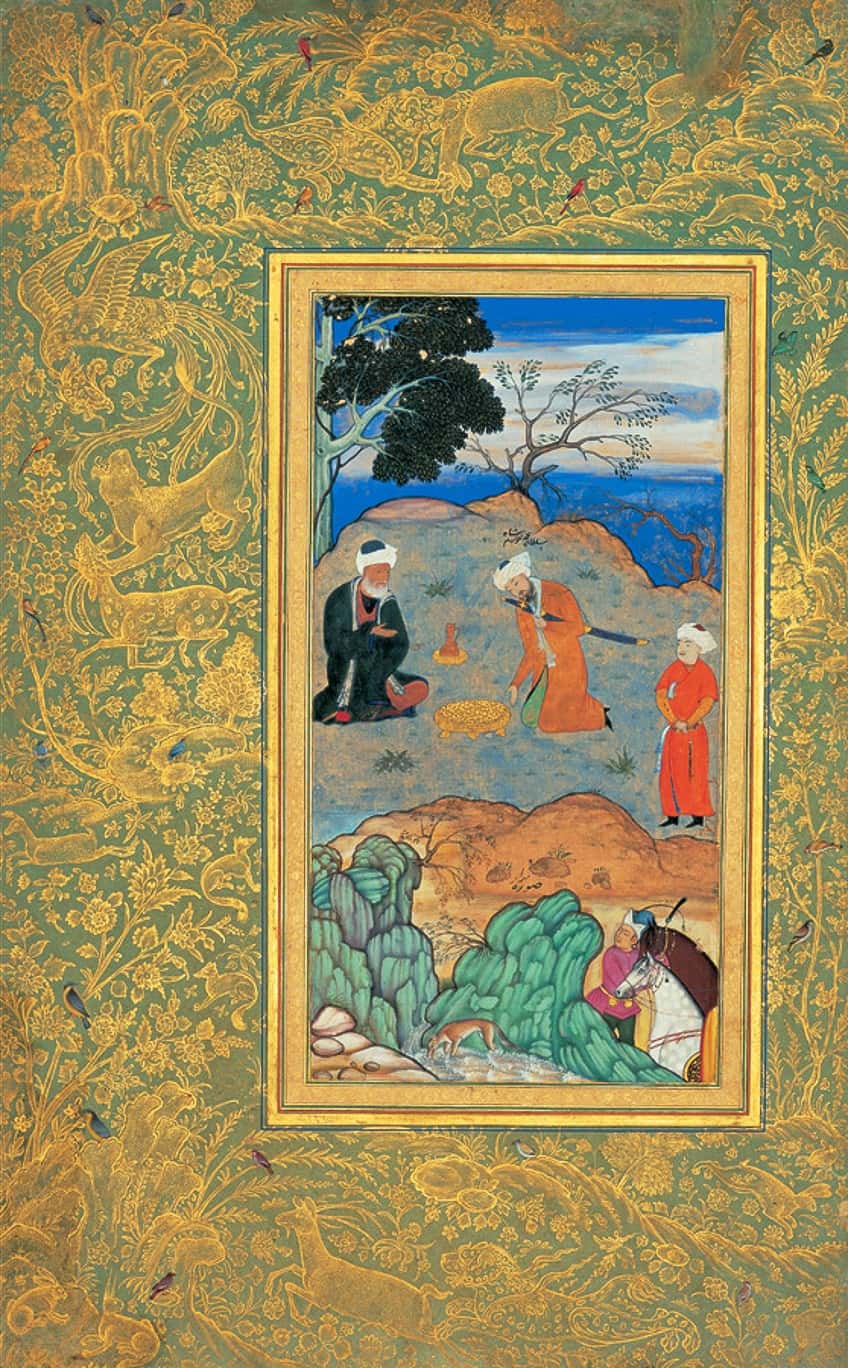

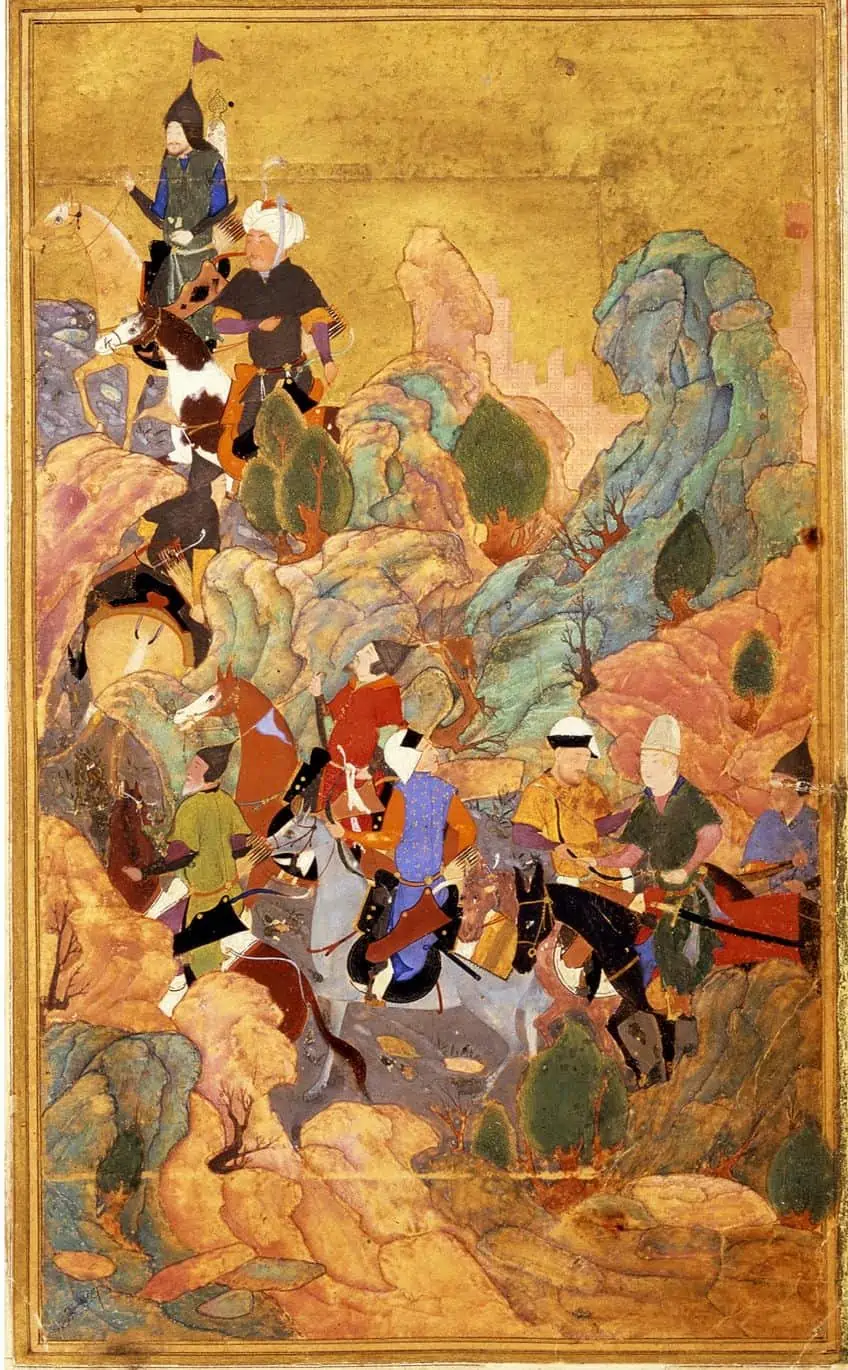

Persian Miniatures

The methods are essentially similar to vignettes in illuminated manuscripts in the European and Byzantine traditions. While there is an older Persian culture of wall painting, the overall preservation of miniatures is significantly greater, and miniatures are the most well-known form of Persia painting in the Western world, with many of the most significant examples housed in Turkish or Western museums.

Miniature painting emerged as an important Persian genre in the 13th century, absorbing Chinese influence during the Mongol invasions, and reaching its pinnacle in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Under Islam, the human form was never fully outlawed in Persian art, and the representation of humans, frequently in huge numbers, is important to the miniature tradition. This was due in part to the fact that the miniature is a private format, maintained in a book or album, and only displayed to those chosen by the owner.

Persian Ceramics

In general, the patterns resemble those of Chinese ceramics, with the manufacturing of white and blue pieces with Chinese designs and motifs, like dragons and chi clouds. The Persian blue differs from the Chinese version in that it has additional subtleties that are more nuanced. In the scroll designs, stanzas by Persian poets, occasionally relevant to the piece’s destination, appear often.

An entirely distinct style of design, considerably rarer, has Islamic symbolism and appears to be influenced by the Ottoman culture, as indicated by feather-edged honeysuckle pendants popular in Turkey.

Persia Paintings

Persian Qajar art is defined as the architecture, and forms of art of the late Persian Empire’s Qajar dynasty, which ruled from 1781 until 1925. The European method of oil painting was now used in Persia painting. Large paintings of festivities and historical events were created as murals for palaces and cafés, and many paintings have an arched top, indicating that they were designed to be inserted into walls.

Portraiture in Qajar artwork has a particular style. The foundations of classic Qajar painting may be seen in the preceding Safavid empire’s style of painting.

During this period, European civilization had a significant impact on Persian culture, particularly in the arts of the king and upper classes. Though some modeling is utilized, big swaths of flattened, dark, rich, saturated colors and heavy applications of paint dominate.

Persia Paintings and Persian Sculptures

As we have learned, Iranian artworks were heavily influenced by the surrounding and various invading elements throughout the region’s long and complex history. Yet, ancient Persian paintings, carpets, ceramics, and other art forms all reflect a distinctly Persian aesthetic that is not only a combination of its influences but unique enough to have influenced other cultures in return. Let’s take a look at some notable examples of the ancient Persian arts.

Gold Model Chariot (c. 4th Century BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 4th century BCE) |

| Date | (c. 4th century BCE) |

| Medium | Gold |

| Location | British Museum, London, England |

Sometime around 1880, a group of traders unearthed this gold model chariot together with 170 other silver and gold items along the Oxus River in what is now known as Tajikistan. The artifacts, known collectively as the Oxus Treasure, are thought to be the most significant remaining relics from the Persian Empire’s Achaemenid era.

The Persian sculpture, which represents the diversity of the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great, depicts two individuals dressed in Medes costume from Iran and the visage of the Egyptian deity Bes on the chariot’s front.

The model’s actual function is disputed and has sparked academic discussion; some say it was a toy, while others believe it was a sacrifice to a temple. The Oxus Treasure is currently housed at The British Museum, together with a second fragmentary gold replica chariot. The model was crafted with extraordinary skill and competence on the part of the artisan.

Both the men and the horses were empty, the result of pieces of gold sheets being cut out and joined together; the bodies were produced by pounding these gold pieces into casts.

The finer elements, such as facial characteristics and clothing, were added afterward. The goldsmith carved the shape of the chariot from a sheet of gold. A wire was utilized for the reins, as well as the spokes and rims of each of the wheels, which were all completely functional.

Portrait of a Young Page Reading (1626) by Riza-Yi ʿAbbasi

| Artist | Riza-Yi ʿAbbasi (c. 1565 – 1635) |

| Date | 1626 |

| Medium | Drawing |

| Location | The Trustees of the British Museum |

The nameless man in this artwork represents the dress of Isfahan, Iran’s capital city during Shah ‘Abbas I’s reign. During this period, international trade and the metropolitan culture created by Shah ‘Abbas permitted a new class of fashionable sophisticates to emerge in Isfahan. Some of these socialites were liberated Christian slaves from Armenia and Georgia who converted to Islam; others were local Iranians.

Riza-Yi ‘Abbasi, the artist of this piece, was a prominent figure in the royal court, recognized for the precision of his brushstrokes and the elegance of his portraiture.

Elements of the artwork shed light on a variety of areas of art and life at the Iranian court in the 1620s. According to the inscription, it is modeled on a prototype by the painter Muhammadi, who would have been working in Herat during Shah Abbas’s time as a prince. This might indicate a sentimental choice of the theme by the Shah rather than Riza.

The figure’s tiny dimensions, as well as the little cabinet on which he sits, recall works by Muhammadi from the 1560s through the 1580s.

Despite these archaic characteristics, the sitter’s lavish gold brocade garment with its enormous blooms and curving leaves represents Isfahan’s style and the sort of sumptuous silk fabrics that were accessible there in the 17th century.

Important Persian Artists

Iranian art is ancient and spans many centuries. Therefore, many of the names of the early artists are forgotten over time. Yet, there are a few names that are still renowned when discussing Iranian art in the present day and are worth mentioning here.

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād (1455 – 1536)

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Date of Birth | 1455 |

| Date of Death | 1536 |

| Place of Birth | Herat (modern-day Afghanistan) |

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād was a renowned Persian artist whose miniaturist technique and work as a tutor had a significant effect on Persian Islamic painting. He was orphaned at a young age and reared in Hert by the painter Mirak Naqqash, who had the support of the Timurid monarchs that governed the city. Behzad trained under his guardianship and was appointed head of the Hert school in 1486, a position he maintained until 1506. Under his leadership, the institution became a more important artistic center than ever before.

The difficulty in recognizing certain works as originating from Behzad’s hand is a key obstacle in precisely judging his works. His students strove hard to mimic his style.

Furthermore, he established himself as the benchmark of perfection in his own time, and buyers of the period would recognize works of quality as being by Behzad with little or no supporting evidence. Only 32 paintings have been firmly assigned to Behzad, all of which were completed between 1486 and 1495.

While Behzād’s work does not constitute a major departure from previous styles, his technical mastery, along with his inventiveness in arrangement and dramatic depiction, as well as his exceptional command of color, established him as the master artist of his day. He could relieve the miniature from rigidity in presentation and excessive preoccupation with detail in a manner defined by harmony, humanity, and elegance.

Behzad brought new life and reality to Persian art.

Many experts regard the five miniatures he produced in a manuscript transcribed in 1488 and now conserved in the Egyptian National Library to be the greatest surviving instances of his art. Behzad’s picture of the construction of the citadel of Khawarnaq, completed in about 1494, beautifully demonstrates his ability to depict a complicated scene in a rich and flowing composition. The work demonstrates meticulous attention and the ability to convey brilliant details while removing unnecessary clutter.

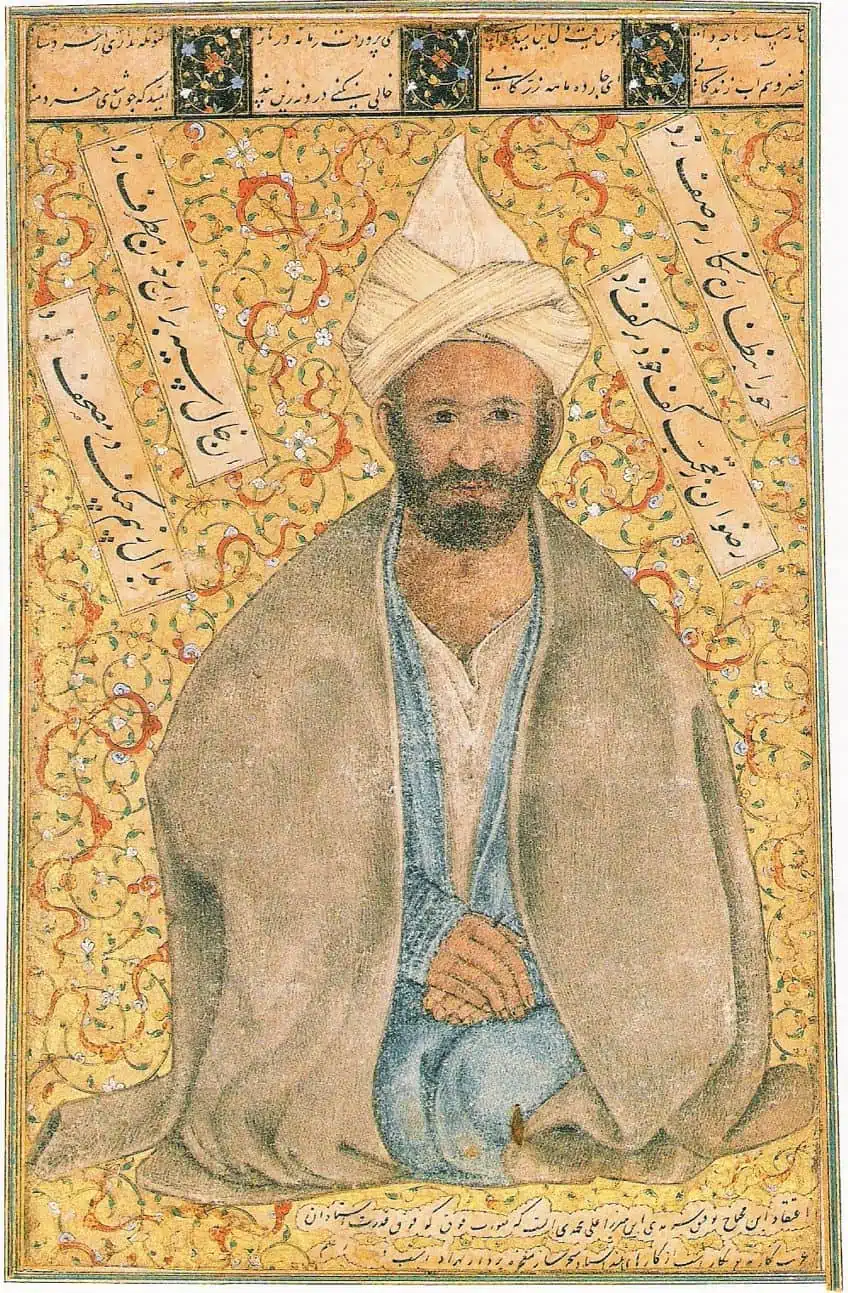

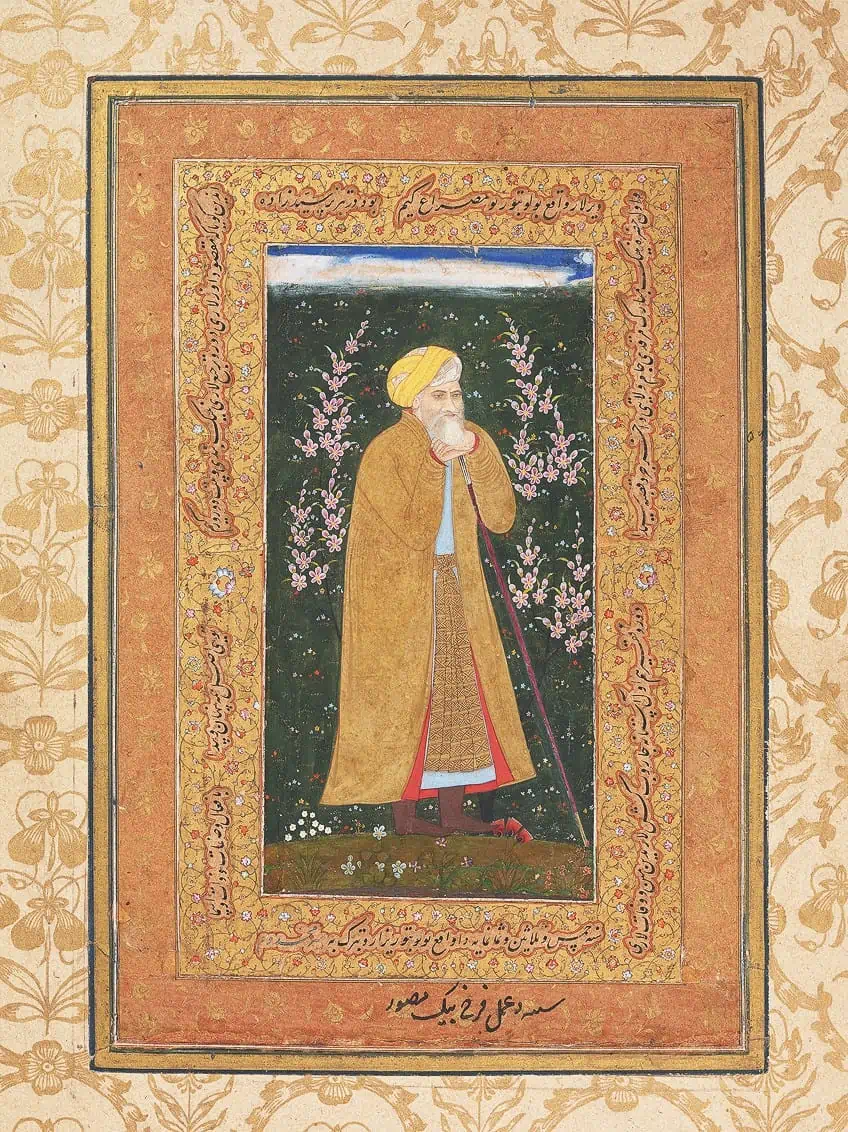

Farrukh Beg (1547 – 1615)

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Date of Birth | 1547 |

| Date of Death | 1615 |

| Place of Birth | Iran |

Farrukh Beg used his interactions with numerous geographical areas in West Asia and urban courts in South Asia, creative techniques, and patrons to improve his artistic skill throughout his career. Beg’s initial style is distinguished by a resemblance to the Persian painting lexicon created under Safavid authority, notably by Shaykh Muhammad and Mirza Ali, which he mastered under Safavid patronage before arriving in Mughal India.

His pictures were filled with individualized gestural portraits, geometric designs in landscapes and clothes, and planar depictions of buildings.

Beg used his creative talents learned in Safavid Iran in his paintings for the Mughal court. Beg proceeded to use hue to divide and harmonize the composition while depicting patterned and finely detailed architectural backgrounds, geometric shapes juxtaposed with sinuous trees, illuminated gold skies, and complex environments with bent and patterned foliage. Due to his unique position enabling him to work alone on all paintings between 1586 and 1596, his esteemed status at the Mughal court enabled him to pour his creative brilliance into his work.

He completely exploited these freedoms in Mughal miniature paintings, yet eventually went on to integrate figural modeling, atmospheric perspective, and folding draperies in his paintings, as shown in the picture of the Old Sufi.

Reza Abbasi (1570 – 1635)

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Date of Birth | 1570 |

| Date of Death | 1635 |

| Place of Birth | Mashhad, Iran |

Reza Abbasi was the son of an artist who painted at the prince’s palace, which was the primary Iranian center for the promotion of the arts at the time. Reza Abbasi’s artistic abilities drew the notice of Shah Abbas when he was still young, and by 1596 he was recognized as having no equal. Soon after, he found himself in bad company, wasting much of his time with sportsmen and wrestlers and paying little attention to his work. Despite the shah’s generosity and favor, he is claimed to have constantly been in financial difficulty.

He no longer worked on royal projects, and his main source of income appeared to be sketches and paintings sold in the market to keep him afloat.

He was able to rebound considerably and continue to work creatively and vigorously until his passing in 1635. His very stylized approach is characterized by figures in exaggerated stances drawn with an exquisitely flowing line and colored in an expressionist, nonrealistic manner. It remains new and noteworthy, although the works of the second phase are rougher and more influenced.

Persian art may be defined stylistically as a fusion of local Persian traditions with Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Greco-Roman art. Given the relatively young age of Persian civilization, this is to be anticipated, as anytime a new culture has developed, it has often drawn substantially from the traditions of older neighbors. Only a little amount of Persian art has survived the millennia. The surviving architecture consists primarily of the ruins of palaces and tombs cut from the rock, with Persian sculpture primarily surviving in the form of wall reliefs, column capitals, and metalwork.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Depicted in Ancient Persian Paintings?

There are several aesthetic and symbolic traits that distinguish Persian paintings from their Eastern equivalents, and these characteristics represent the creative and philosophical perspectives of Persian painters. Persian miniatures are devoid of any specific location or time, which imbues them with a transcendental dimension, thanks in part to the impact of Sufism and its system of thinking. Even if the moon, stars, or even the sun are shown in the sky, indicating whether it is day or night, they have no influence on the rest of the picture because there is no play of shadow and light in the design.

What Was Depicted in Ancient Persian Sculptures?

Along with animal capitals, large-scale Persian sculpture has survived mostly in the shape of reliefs on cliffs and palace walls. Some are highly stylized and have a distinct Mesopotamian flavor, while others have the stunning realism of classical Europe. These two opposing aesthetics may be observed in all kinds of Persian sculpture. Aside from massive sculptures, of which only a small portion has survived, the Persians are responsible for a wonderful corpus of metallurgy. They are also known for their elaborate and eye-catching carpets and finely designed pottery. Ancient Persian artworks, such as miniatures, are still valued today for their lack of cultural influences while retaining a distinct style.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Persian Art – A Deep Dive into Ancient Persian Arts.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 6, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/persian-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 6 October). Persian Art – A Deep Dive into Ancient Persian Arts. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/persian-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Persian Art – A Deep Dive into Ancient Persian Arts.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 6, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/persian-art/.