Political Art – Uncovering the Use of Political Propaganda in Art

Is political art distinct from other forms of art? Could it even exist separately from politics, given that political truth is known to be the controlling force in all facets of humanity? Since its inception, art as a political statement has been inextricably linked to society, and throughout its history, creatives have consistently reflected on the present to communicate the artistic reality to the public at large. Social issue art represents or, more accurately, contests the multiple models of truth, beauty, and the good found in societal reality.

Contents

- 1 The Role of Famous Political Art

- 2 Famous Political Art

- 2.1 An Excrescence; – A Fungus; – alias – a Toadstool Upon a Dunghill (1791) by James Gillray

- 2.2 The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David

- 2.3 Europe After the Rain II (1942) by Max Ernst

- 2.4 The Problem We All Live With (1964) by Norman Rockwell

- 2.5 Free South Africa (1985) by Keith Haring

- 2.6 We Don’t Need Another Hero (1987) by Barbara Kruger

- 2.7 My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love (1990) by Dmitri Vrubel

- 2.8 The State (1993) by Richard Hamilton

- 2.9 Soldiers Painting Peace (2007) by Banksy

- 2.10 With Flowers (2013) by Ai Weiwei

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

The Role of Famous Political Art

Mimesis, the act of artistic development, is inextricably linked to the idea of the real world, according to Aristotle and Plato. As a result, the art world occupies a semi-autonomous position because it is a separate discipline of creation free from rules, functions, and norms.

It is also because it is intricately linked to and reliant on artistic production, curatorial practices, display methods, socioeconomic circumstances, and political climate.

However, throughout the ages, political propaganda in art has been rife with patrons commissioning works that paint them or their ideals in a good light. Yet, in times of significant political change, many social issue artists and creative professionals choose to portray the circumstances in their artistic processes on their own, resulting in political paintings.

Art as a Political Statement

Art can be linked to politics in a variety of ways, and the realm of social issue art is far more diverse and richer than a single term that can be reduced to just political propaganda in art. There are numerous strategies for obtaining political interaction in art, which includes a wide range of artistic initiatives ranging from simple gestures to sophisticated conceptual artworks with clear civic participation aimed at real political change.

And yet, when debating political paintings, we must remember that art is not and cannot be whittled down to a mere tool for political action, even if it can be an integral part of activist exercises – art must also be aesthetic.

The aestheticization of politics was widely criticized in the 20th century as an attempt to conceptualize everyday life (and social and cultural actions) as inherently artistic and to incorporate political values into art by relabeling it as a form of art in hopes of normalizing liberatory or radical practices and confine them to the fully independent field of art.

This was a concept introduced by Walter Benjamin and eventually developed further in the Frankfurt School.

It was also a philosophical response to how Fascist dictatorships in Europe appropriated art. According to this hypothesis, the politicization of “aesthetic appeal” – a kind of radical social practice that redefines the profession of art and gives art a wider political or, more accurately, liberatory character – would be the complete opposite of these practices of aestheticization.

Liberating Art from Fascists

The main goal of releasing art from corrupting political ideologies like nazism, fascism, or any other policy agenda that is reductionist and dangerous is to give it back its independence. Any artistic activity must be free from political purpose, particularly when it violates its status when it is turned into a tool of political propaganda in artworks for the ruling system.

Recognizing the core values of social issue artists and famous political art as a whole depends on the fundamental act of refutation or dissent from the detrimental or negative aspects of politics.

As an act of creation and involvement in the physical world, social issue art, as a type of social action, is a very potent tool of ideological ingenuity because it depicts the world, not as it is, but rather in a better or more advanced state.

The Role of Political Paintings

We must be cognizant of the hazy boundaries between art and social movements, mainstream press, and society when debating the function of art in today’s world. It is difficult to define not only the idea of art but also its place within society in the many instances of artistic works.

In modern societies, it is crucial to put aside romantic notions of art’s purpose while also insisting on persistently challenging prevalent politics within the arts and defending the innate freedom of speech and expression that exists within them.

Political art has always played a crucial role because it is one of the few uncompromised forces for liberatory action and exists as the perfect environment to raise questions over what is and what might be considered decent, reality, and beautiful.

Famous Political Art

A common observation is that a talented artist has a free spirit, which is frequently a potential danger to those who want to preserve the status quo in politics. Politics and art have historically had a close relationship. Through ownership and references to its corrupting influence, power has been reflected in art throughout different historical eras and cultures. Artists from all over the world are responding to current affairs and their social implications, and they are driven to make observations on the public sphere, becoming a source of debate and even a driving force behind changes in society and politics.

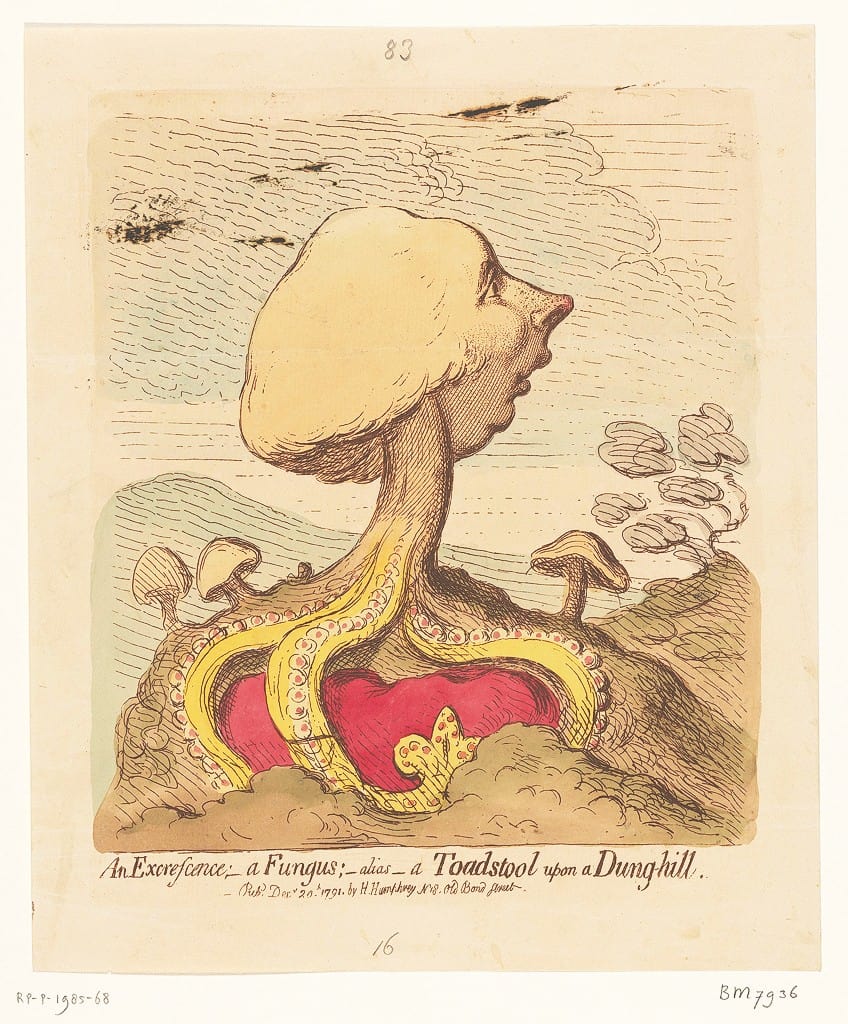

An Excrescence; – A Fungus; – alias – a Toadstool Upon a Dunghill (1791) by James Gillray

| Artist | James Gillray (1756 – 1815) |

| Date Completed | 1791 |

| Medium | Hand-colored etching |

| Current Location | British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

After serving as an engraver’s apprentice, James Gillray enrolled in the newly established Royal Academy of Art in 1778. He created his distinct caricature fashion here. At the same time, he started writing satires, and shortly after, he started the most important relationship of his life with Mrs. Humphrey, the publisher of his prints. Until his death, he would reside above her print shop. In this specific political parody, William Pitt is portrayed as an ideological mushroom that has grown dunghill-like on the crown.

Pitt regularly proved to be a suitable target for the caricaturist’s humourous gaze in the public sphere.

Pitt was progressively portrayed as an audacious trickster determined to limit the influence of the royal family as a direct consequence of the Regency crisis, during which King George III gradually lost his authority. The comedy of today is very similar to the comic caricature of 18th-century prints. It depicts a distorted but easily recognizable world of individuals, locations, and objects.

Innuendo with sexual overtones is also its main source of humor. Nevertheless, the satiric caricature is very distinctive.

It shows us an entirely unreal world, where lawmakers can be themselves as well as boots, butterflies, pigs, bats, and dogs, where fictional characters like Britannia and John Bull can converse with historical figures like Addington and Napoleon, where ministers can spew cash, and the king can feed on gold. It is a realm of metaphor rather than a simile. William Pitt “is” that fungus, not just “like” it. The metaphor has come to life right in front of our eyes, and Pitt’s face alone proves how appropriate it is.

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825) |

| Date Completed | 1793 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium |

The history of this painting is intriguing. During the French Revolution, Jean-Paul Marat was a very well-liked revolutionary French politician, and journalist who also happened to be Jacques Louis David’s close friend. His journalism was renowned for its feisty tone and hardline stance on the majority of important concerns at the time, such as supporting the poor and middle class’s basic human rights and being very unyielding toward the establishments and leaders.

He was debatably the most progressive voice of the French Revolution toward the final stages of his life.

So, on the Saturday evening of the 13th of July, 1793, in Paris, Jean-Paul Marat just so happened to be soaking in a bath that was medicinal for his skin condition. A Caen resident named Marie Corday, a royalist entered his room and plunged a knife into his chest. The day before, she had purchased the knife from a nearby shop.

Convinced that Marat was a troublemaker who must die at any cost, she made up her mind to carry out the deadly deed, pretending to offer him the names of dissidents. After Marat’s death, Marie Corday was taken into custody almost immediately. She was guillotined and killed four days later.

Since David was a Neoclassical painter, one might have anticipated a nod to classical antiquity. Nevertheless, with this famous political artwork, he went in a completely different direction.

In essence, it is the portrayal of a modern subject in a modern environment. According to Jacques Louis David, he did this to demonstrate to the public the state in which he discovered Marat. He did, however, take a few artistic licenses, so the painting is not intended to be a precise photographic representation of what transpired. For instance, Marat perished with a knife pierced into his chest when he was assassinated.

Europe After the Rain II (1942) by Max Ernst

| Artist | Max Ernst (1891 – 1976) |

| Date Completed | 1942 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Current Location | Wadsworth Atheneum, Connecticut, United States |

This continues to remain Max Ernst’s greatest masterwork, in which psychological desolation, sheer fatigue, and anxieties of the devastating power of military aggression combine. The title refers to a prior painting that was created from oil and plaster (and painted on plywood) to generate a fictitious relief map of a rebuilt Europe and finished in 1933, a year in which Hitler took power.

Ernst’s techniques are extensively used in the artwork, which depicts a devastated landscape evocative of both mangled wreckage and decayed organic expansion.

Are we witnessing an apocalypse or unchecked cancerous growth? True to Ernst’s techniques, there is no conclusive interpretation, but given his background, his escape from the Gestapo, and his disdain for the devastation caused by war, it’s not difficult to detect a muted melancholy. The figures might be overgrown statues or vaguely mythical survivors of a long-forgotten war in a landscape evocative of classical paintings of ruins.

A female figure is in danger from a soldier with a bird’s head helmet who is brandishing a spear, or perhaps a crumpled battle standard. Maybe it’s a metaphor for the fall of European civilization.

It might be an indictment, demonstrating that when the noble exterior of civilization is removed, what is left are tumultuous masses of half-formed nightmares. Regardless of your perspective, this striking illustration is a true masterpiece of Ernst’s output because it raises more questions than it answers.

The Problem We All Live With (1964) by Norman Rockwell

| Artist | Norman Rockwell (1894 – 1978) |

| Date Completed | 1964 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Norman Rockwell Museum, Massachusetts, United States |

Suppose that you were only six years old and attending a new school for the first time. You’re dressed in a distinctive outfit. You have pencils and a notebook. You feel both excitement and a little bit of anxiety. There are official-looking men in suits waiting to accompany you inside the building. Outside, a hysterical crowd has gathered. Possibly a parade, you think. Warm greetings from your teacher, but where are your schoolmates? Why are you the only pupil present? Why aren’t there any other people around to play with at the playground or to have lunch with?

Although you are young and confused, you are courageous and do not cry because your mother has asked you to behave.

Ruby Bridges actually experienced this on the 14th of November, 1960, during her first day of class at William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans. After a governmental court ordered the integration of the New Orleans school system, she was the very first African-American child to enroll in the school. White parents withdrew their kids from school so they wouldn’t have to sit next to a Black girl because of the widespread outcry.

Ruby was isolated in a classroom for an entire school year. Ruby’s fearless journey to school on that November day is depicted in the painting.

She obediently follows two faceless men – who are actually federal marshals identifiable by their yellow armbands – past a wall covered in racist graffiti and tomato juice. A few years after the young black girl made her entrance at the school, Rockwell painted the scene, which was completed at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. It is now regarded as a representation of that conflict. Bridges never managed to meet Rockwell, but she came to respect his decision to share her story as an adult.

Free South Africa (1985) by Keith Haring

| Artist | Keith Haring (1958 – 1990) |

| Date Completed | 1985 |

| Medium | Poster |

| Current Location | Multiple prints |

Haring’s Free South Africa series aimed to address South African Apartheid by using his distinctive artistic approach to represent difficult social issues. In 1986, Haring tirelessly worked to rally opposition to apartheid in New York City by printing and distributing about 20,000 Free South Africa posters. “Control is evil”, as Haring noted in a journal entry.

All accounts of the “expansion,” “colonization,” and “domination” of white men are replete with horrifying specifics about the mistreatment of people and the abuse of power.

Each print in the series depicts two stick figures fighting, and as the series goes on, we see this fight develop. Haring depicts the interaction between the white minority and the black majority in South Africa during the decades of institutionalized racial segregation using his bold, linear style.

The stark contrast between the black majority and the handful of white people who held social and political power at the time is represented by the black character on the left being rendered significantly bigger than the white character.

By depicting the white figure holding a rope around the black figure’s neck, Haring effectively illustrates the power disparity between white and black men. Each image in the series is given movement by the use of radiating lines and dashes, which convey the anger of the black figure and the concern of the white figure that is about to be decimated.

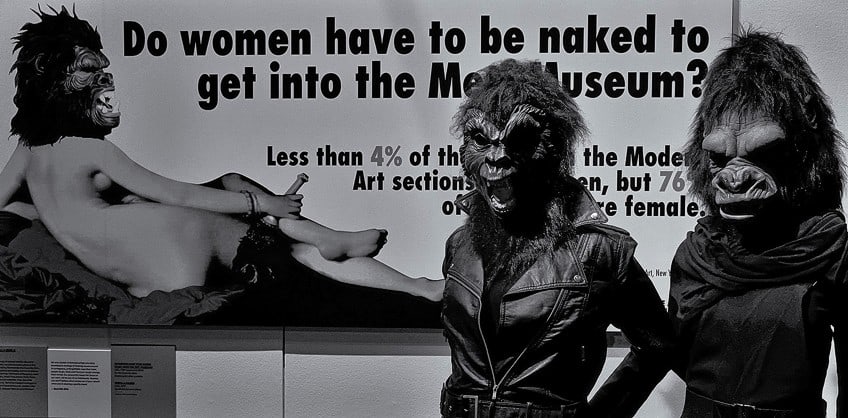

We Don’t Need Another Hero (1987) by Barbara Kruger

| Artist | Barbara Kruger (1945 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 1987 |

| Medium | Screen-print on vinyl |

| Current Location | Whitney Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

There are several examples of Barbara Kruger’s work with mass-media representations of women. She enjoys using images of women as her poster pics and pairing them with text to imply the underlying meaning of female vulnerabilities and subservience that the images were intended to convey. As a postmodern feminist, she uses her artwork to communicate feminism and women’s rights issues. She completed the billboard project We Don’t Need Another Hero in London in 1986. We only need one hero, according to another interpretation of the phrase “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” which refers to the young boy and girl in the background of the texts.

In this instance, Barbara Kruger used the word “hero” to undermine the gender roles depicted by society because being a hero requires more than just physical prowess.

In this photo, the girl is pointing to the boy’s arm as she leans over to him. In reality, the girls pretend to respect the boys’ strong muscles in the picture, because they are a reflection of the actual world in which women are subtly in charge and use their language, gestures, and poses to influence men’s behavior, allowing the men to feel powerful and in charge by displaying their physiques.

Heroes can also be women – they just use their brains more than brawn.

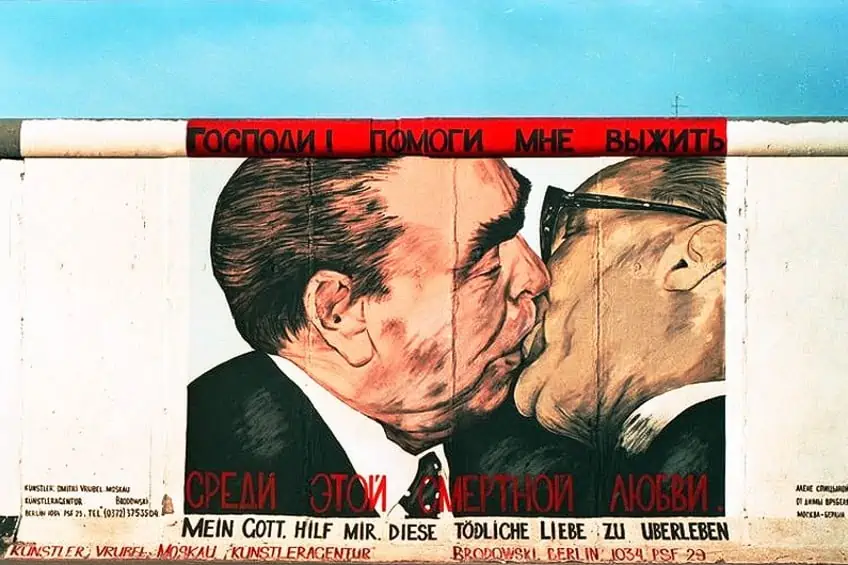

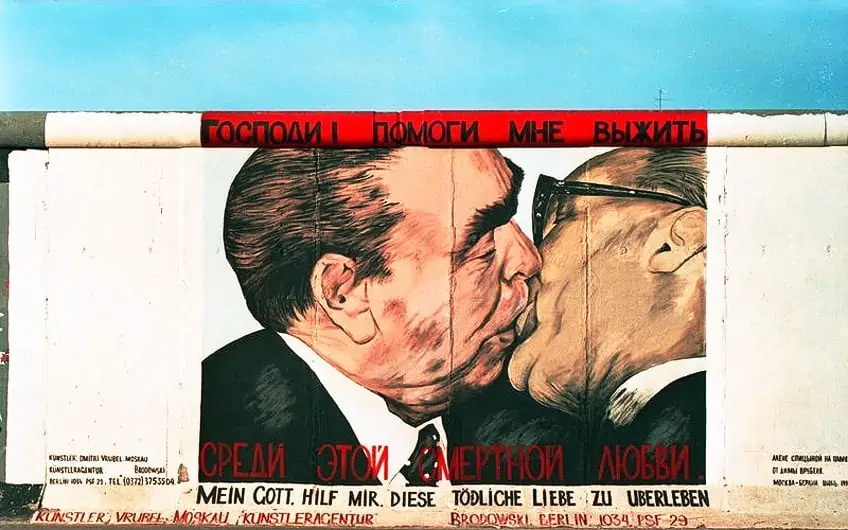

My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love (1990) by Dmitri Vrubel

| Artist | Dmitri Vrubel (1960 – 2022) |

| Date Completed | 1990 |

| Medium | Street Art |

| Current Location | East Side Gallery, Berlin, Germany |

Dmitri Vrubel is a well-known critic of political systems and is best known for his mural on the Berlin Wall. The well-known tourist destination was built 32 years ago, in 1990, and it is still among his most well-known creations. The artwork was “a picture for Berlin”, and Vrubel had painted it “for the Germans”.

In addition to reflecting on the historical context of its creation, the image elevates the conversation about the current state of affairs and the ongoing conflict in Europe.

The duality of powers that split the world into two adversaries and nearly brought about a nuclear war is what predominates in Western accounts of the Cold War era. Vrubel’s mural offers a satirical but thoughtful commentary on all political unions likely to lead to disaster as a genuine threat hangs over us once more. The famous mural on the Berlin Wall has a lengthy caption that reflects the artist’s thoughts more on what the two people in the picture stand for than on what is being portrayed.

It was based on a 1979 photograph of a kiss between East German leader Erich Honecker and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and also features inscriptions in Russian and German.

It depicts the moment of political unification between the Soviet Union and GDR following the signing of a ten-year agreement of mutual support. This moment is often referred to as the “Fraternal Kiss”. Although there are other individuals from the political elite gathered behind the couple in the original image, Vrubel’s rendition concentrates solely on the couple as they kiss in front of a white background.

The State (1993) by Richard Hamilton

| Artist | Richard Hamilton (1922 – 2011) |

| Date Completed | 1993 |

| Medium | Oil and enamel paint |

| Current Location | Tate Museum, London, United Kingdom |

Richard Hamilton’s depiction of a British serviceman on patrol conveys the unease that comes with the army’s ambiguous position between the two factions fighting in Northern Ireland and the multiple roles that the troops must play. The soldier is simultaneously armed and on the defensive. In this image, Hamilton aimed to convey the impression that the soldier is moving backward. British troops roaming in Northern Ireland are accustomed to walking back-to-back, about 100 yards apart, to make sure they are protected from both directions.

This notion is also connected to the artist’s belief that the British want nothing to do with Northern Ireland. He portrays the soldier as a youthful, hesitant conscript.

The word “spuds”, an English term for the potato, a vegetable closely associated with Ireland, is written on a giant billboard behind the serviceman. Cockney Londoners also use the term to describe Irish individuals. The uncertainty of the soldier’s situation is reflected in the artists’ use of trompe l’oeil in the treatment of the combat uniform.

While some of the fabric is painted, some of it is the actual fabric that has been placed on the picture’s surface.

Along with his clothing and visored headgear, the camo markings on his face contribute to his unsettled expression and join this artwork with its two companion diptych pieces in a theme that runs through many of Hamilton’s works: the functions of attire and artifice in the appearance of the human image.

Soldiers Painting Peace (2007) by Banksy

| Artist | Banksy (1974 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 2007 |

| Medium | Street Art |

| Current Location | Tate Britain Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

In 2007, after being featured in an extensive collection at the Tate Britain gallery in London, Banksy’s stenciled anti-war artwork gained notoriety. The selection was a reproduction of the Bristol street artist’s “artistic display” that was allegedly in violation of a rule prohibiting unpermitted protests within a certain radius of the Houses of Parliament when it was taken down.

In this picture, two combat-ready soldiers are planning to portray a peace sign on a wall while warily scanning their surroundings.

The first is squatting while holding a machine gun, and the second is trying to finish the sign while holding a brush dunked in a container of red paint. Since the soldiers in this piece are anti-war protesters, the artwork encourages a statement against conflict and violence. Millions of people started protesting the UK invasion of Iraq in 2003, including members of the military.

The concept of soldiers “keeping the peace” in Banksy’s works of art meant defying the government’s policies. Uri Geller, a well-known magician, was immediately enamored with the piece.

“I’m strongly opposed to weapons”, Geller told the newspaper, “So I managed to pull over and ran across the garden to ask if I could buy the painting when I rolled past Brian and noticed it. I believe I gave a $5,000 offer”. “Uri expressed interest in the painting despite my assurances that it wasn’t for sale”, according to Haw’s account of the incident. “He proposed $1,000. He was extremely irate”. Several law enforcement officers swept Haw’s camp in the early hours of the morning shortly after the Geller incident and deleted 40 meters of placards, along with the Banksy one.

With Flowers (2013) by Ai Weiwei

| Artist | Ai Weiwei (1957 – Present) |

| Date Completed | 2013 |

| Medium | Photos |

| Current Location | Performance piece |

As he had done every morning for the past 18 months, Ai Weiwei put a flower bouquet in the bicycle basket outside his Beijing studio on that Wednesday. Carnations and Baby’s Breath were among the choices. He had picked sunflowers the day prior. He gave lilies to begin the week. China’s infamous dissident artist displayed his flowers every day in protest of the seizure of his passport for more than a year and a half.

The piece, titled With Flowers, combines performance art and protest. but not anymore: that Wednesday, the artist revealed via Instagram that the Chinese government had finally returned his passport after four years.

The protest endured for about 600 days. On the 30th of November, 2013, more than two years after being imprisoned, Ai Weiwei began the performance. He situated the flowers outside of the aquamarine door at home to both his studio as a remarkable record of his imprisonment. They were all properly documented on Flickr and featured powerful arrangements that were rarely boring. Ai is both active and knowledgeable on social media, which is part of what got him into trouble with the law. Through posts on Instagram, Flickr, and Twitter, Weiwei’s flowers were seen far beyond the basket on his black bicycle.

The politically charged activity is typical of the work that has made Ai Weiwei well-liked both domestically and abroad. With Flowers is a piece of endurance that leaves the audience delighted rather than worn out.

Similar to his Sunflower Seeds installation from 2010, which featured millions of earthenware seeds that were each meticulously made by hand in Jingdezhen workshops, it is repetitive but deceiving. It also has something to do with the work that made him a target of Chinese authorities. Ai Weiwei set out to identify the more than 5,000 kids who died when their schools collapsed in Sichuan after the devastating earthquake there in 2008.

Many world-renowned artists have, at one time or another, found themselves playing the part of social issue artists. Although many people would prefer that they just stick to painting aesthetically pleasing pictures, many artists have taken it upon themselves to raise awareness of certain political issues with their famous political artworks. While some of the earlier paintings commissioned by royal patrons lead to many examples of political propaganda in art, not all political paintings were paid for by someone else. Most modern artists use art as a political statement to make others aware of topics that they find significant.

Take a look at our political artwork webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Was There Political Propaganda in Art?

Art can be used to effectively convey a message visually to a large audience. Just like with religion, there are times in history when certain political figures wanted to convey a message or set of morals to their populace. Many people in the past were illiterate and, therefore, were not able to get their information through the written word. Many churches ad governments would pay artists to depict certain themes that carried a message. In this way, they could use heroes and characters from history and mythology to tell a specific story.

Should Artists Use Art as a Political Statement?

Although there are perhaps many people who would prefer if artists and musicians kept their political views to themselves, many creative people see it as their duty to use their platform to educate and inform people about certain injustices in this world. As the arts are for self-expression, it is not really up to anyone else to decide what artists wish to depict. Art is a powerful medium, and many famous political art pieces have managed to have a positive impact on the world, encouraging real change with their emotive social issue artworks.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Political Art – Uncovering the Use of Political Propaganda in Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. November 12, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/political-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 12 November). Political Art – Uncovering the Use of Political Propaganda in Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/political-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Political Art – Uncovering the Use of Political Propaganda in Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, November 12, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/political-art/.